General von Manstein and the Führer.

General von Manstein and the Führer.

SO FAR AS France and England were concerned, the war was being conducted in the most soporific way, as if both countries were waiting for Hitler to make the first move and still anxious not to give him a reason for attacking. Behind the scenes, however, a whole first act of a fatal drama was being played out—indeed the major players, many of them more or less unsuitable for their role, were already in place.

At the very beginning of the war Secretary of State for War Hore-Belisha, with Chamberlain’s consent, had chosen the then chief of the Imperial General Staff, General the Viscount Gort, to command the British Expeditionary Force in France and General Sir Edmund Ironside to replace him as CIGS. Ironside had expected to be given command of the BEF himself and was dismayed on September 3 when it went to Gort instead, who he judged had already been promoted far beyond his capabilities.

Leslie Hore-Belisha visits the troops, 1939.

It was the reverse of what everybody in the army had assumed would happen when war came. Ironside was enormously tall and physically impressive (hence, following British military tradition, his nickname was Tiny), he spoke French well (and also German), and he had attended prewar German Army maneuvers as an observer and met not only the senior German commanders but even Göring and Hitler. He seemed ideal to command the BEF.

Gort was an aristocrat (John Standish Surtees Prendergast Vereker, 6th Viscount Gort) and outstandingly brave, one of the most decorated officers in the British Army, having won the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest award for valor, three Distinguished Service Orders, and the Military Cross in the 1914–1918 war, but he had neither the brains nor the temperament for high command; he fussed over details like a sergeant-major and had no discernible gift for seeing “the big picture.” As CIGS he had been essentially a figurehead, and he particularly disliked dealing with politicians—not a good recommendation for the commander in chief of the BEF, who needed to be at once a strategist, a politician, and a diplomat.

Lord Gort was a popular choice to command the BEF outside the circle of his fellow generals. He was exactly the kind of Englishman the French profess to admire: heroic, modest, and profoundly unintellectual. His title and his Victoria Cross won him the respect of the British press, and although the notion of “public relations” would have been repugnant to Gort, he, unlike his predecessors in World War One, made an effort to fraternize with British war correspondents, and even invited them to lunch in his mess. Gort was particularly forthcoming with the dashing, witty, and well-informed young Times war correspondent to the BEF, Harold “Kim” Philby. Naturally, for Lord Gort, as for most Englishmen of his class, the Times was a cut above any other newspaper, so he could talk more frankly with Philby than with most reporters. What he did not, of course, know was that Philby had been a spy for the Soviet Union since his Cambridge days, and passed on every scrap of information from Lord Gort to Moscow, via his Soviet contact in Paris. Since Soviet Russia was then an ally of Nazi Germany, that information was no doubt passed on immediately to Berlin. There would be no surprises about the plans and the strength of the BEF when the Germans finally attacked, thanks to Philby, who went on to decades of further betrayal when he was recruited away from the Times by MI6 later in 1940.

It may well be that Chamberlain should have quietly sought further advice before allowing Hore-Belisha to give command of the BEF to Gort, but the prime minister’s lack of interest in military affairs was notorious. He should certainly also have given more thought to the role of the BEF itself. Although the BEF would eventually grow to over 300,000 men (including its RAF Air Component), it was dwarfed by the French Army, which was over 5,000,000 men strong, 3,500,000 of them in Metropolitan France alone. In view of this huge disparity in numbers the Chamberlain government had agreed from the beginning that the BEF should take a place in the “line of battle” of the French Army, and that the commander in chief of the BEF should come under the orders of the French commander in chief, General Maurice Gamelin. The commander in chief of the BEF would retain the right to appeal to his own government in case he disagreed with the orders he received, but except under extraordinary circumstances it was hard to imagine that Gort was the right man to do this. His natural disposition was to obey his orders, not to argue about them, and by the time he finally made use of this right it was almost too late. Gort’s own chief of staff, the acerbic Lieutenant-General Henry Pownall, was of the opinion that Gort was better suited to a “regimental” command (that is, a lieutenant-colonel’s job) than as the British commander in chief in France.

General Gamelin contemplates the map of Europe—and apparently, the English Channel.

Lieutenant-General Pownall.

During the First World War the British Expeditionary Force had not been placed under French command until the crisis of March 1918 when Germany’s last great offensive, Ludendorff’s Kaiserschlacht, threatened to overwhelm the French, British, and American armies. In the emergency the Allies reluctantly agreed to accept General Ferdinand Foch as Généralissime, or Allied Supreme Commander. Gort’s BEF received its orders from France’s Grand Quartier Général, filtered down through several levels of command, and took its place between two French armies facing Belgium, to its north the French Seventh Army, to its south the French First Army.

As they had in the previous war, the French insisted on keeping a French army between the BEF and the Channel ports, just in case the British got cold feet. The role the BEF was to play when the Germans finally attacked was subordinated to Gamelin’s strategic vision, and also to the surreal confidence of the Belgian government in its policy of strict neutrality.

Gamelin’s plan was known as Plan D because it involved an advance to the Dyle River in Belgium, perhaps unfortunately because in the French Army “le système D” stands for “débrouillez-vous,” or more rudely “démerdez-vous,” the equivalent of “sort it out for yourself” when things go wrong. Gamelin assumed that the main German attack would come through neutral Belgium, as it had in the First World War, and that Germans might attack the Netherlands as well this time, a neutral country they had avoided in 1914. He did not think the Germans would dare to attack the Maginot Line in major force, and like almost everybody else he assumed that the Ardennes Forest—that is, the southernmost spur of Belgium and Luxembourg that extends from Namur in Belgium to Montmédy in France, where the Maginot Line ended—would be inappropriate for a major attack because of its hilly, heavily wooded terrain, which contained too many small streams and too few major roads. Besides, the Meuse River would present a major natural obstacle for the German armored forces as they emerged from the Ardennes. In Gamelin’s opinion, the Maginot Line could hold the Germans indefinitely and it would take them at least two weeks to cross the Ardennes in force, therefore the first and major blow would come in the north through Holland and Belgium, with their flat terrain and excellent roads, hence good tank country. It was there that the Germans must be met, Gamelin believed, and counterattacked boldly and with maximum force.

* * *

This had in fact been the original German plan, and it presented the Allied armies with an unanswerable question: What would Belgium do? Belgium’s neutrality was a sacred cause—the German breach of Belgian neutrality in August 1914 had been the deciding factor in bringing the United Kingdom into the war. The British government did not go to war to support France in its hour of need, the British went for “plucky little Belgium,” to defend its neutrality, which Britain was bound by treaty to support. Of all the many mistakes made by the Kaiser’s Germany, the most serious (and the earliest) was the decision to ignore what the Kaiser notoriously dismissed as “a scrap of paper” and invade Belgium, since by doing so he would automatically bring Britain and the British Empire into the war against him.

Nobody doubted that Hitler would not hesitate to breach Belgium’s neutrality, and Holland’s too if it suited him, but the French and the British could not. Thus the advance to the Dyle River, which was at the heart of Gamelin’s plan, could not take place unless the Belgium government invited them to, or until the Germans had crossed the Belgian border, which effectively placed the timing of the Allied attack entirely in the hands of the Germans, or those of the king of the Belgians. This fact did not escape General Alphonse Georges, commander of the northeast front, who had no faith in Plan D and disliked General Gamelin.

Churchill and General Georges.

The feeling was mutual. From the beginning of the war General Gamelin had placed his headquarters—the Grand Quartier Général—in the gloomy Château de Vincennes in the suburbs of Paris, determined not to be influenced by politicians or by General Georges, while Georges moved his headquarters as commander of the northeast front as far away as he could from General Gamelin. The Château de Vincennes was a curious choice—it was the scene of many historical tragedies going back to the fourteenth century, and its former moat had been used for executions by firing squad in the past, and would be used again for that grim purpose by the Germans from 1940 to 1944.

General de Gaulle and the king.

In order to avoid having to meet face-to-face, Gamelin and Georges communicated by courier or, more rarely, by telephone, although there was no guarantee that the telephone lines were secure. Oddly, there was no radio at the GQG, both because Gamelin feared the Germans would intercept and decode messages, but also because he did not want messages from General Georges disturbing the Olympian calm of his planning for grand strategy, or upsetting his sacred routine. Gamelin was not only physically remote and protected by his devoted staff from outside influence within the sprawling confines of the Château de Vincennes, a kind of military Dalai Lama; his was in any case a somewhat withdrawn personality, “smooth, secretive, non-committal.” Georges, on the other hand, was of a more outgoing nature—he had a good deal of that charm and taste for good living that the British find reassuring in a Frenchman.

King Leopold III of Belgium

Just before the beginning of the war the ubiquitous Spears had brought his friends Churchill and Georges together for a lunch at a fashionable restaurant in the Bois de Boulogne, and by the end of the long lunch, over “wood strawberries soaked in white wine,” the two men found themselves of one mind. Churchill warned Georges about the mistake of thinking that “the Ardennes were impassible to strong forces,” as both Marshal Pétain and General Gamelin believed, while Georges made clear his opinion that King Leopold III of Belgium “was reputed to be much under German influence,” and intended to hold the Allies “at arms length.” These two concerns would be at the root of the problems facing the Allies in 1939 rather than the relative strength of the Allied and German armies, or German superiority in ground attack aircraft.

The assassination of King Alexander of Yugoslavia, in which General Georges was badly wounded.

Owing to the intricacies of the French command system, General Gamelin gave direct orders to all the French Army commanders worldwide except General Georges, who had direct command of the Allied armies facing the Germans. On the other hand, since Gamelin was commander in chief, he controlled the flow of troops and supplies and had the power to promote generals, who in the northeast therefore looked to Georges for their orders, but toward Gamelin at the Château de Vincennes for their future.

The British liked Georges more than the unapproachable Gamelin—Georges seems to have won over General Lord Gort easily enough, no small achievement given the uneasy relationship between British commanders of the BEF and French generals in World War One—but some questioned whether Georges had recovered completely from the life-threatening wound he had received during the assassination of King Alexander of Yugoslavia at Marseille in 1934. Was he the same man he had been before the incident? It was the length of his recovery, together with Daladier’s fears that Georges was too far to the right politically, that had led to making Gamelin the commander in chief in 1935 instead of Georges, who was merely made Gamelin’s deputy and “eventual successor” instead, much to his chagrin.

In the meantime it was unclear to both the British and the French whether Lord Gort would receive his orders from Gamelin or from Georges. Not even Tiny Ironside, who was as bold and as blunt as he was tall and broad-shouldered, was able to ascertain this vital point from Gamelin, who was theoretically his counterpart. This was only one ingredient, but an important one, in a recipe for disaster.

The Belgian problem was insoluble. Neutral Belgium and the Netherlands were like the proverbial deer caught in the headlights of a huge truck speeding toward them, driven by Hitler. In order to protect their neutrality they could not enter into formal staff talks with the French and the British; on the other hand they both expected that the Allies would come to their rescue immediately if they were attacked. Since Gamelin assumed that they would be attacked, he blithely added their military strength to his own: twenty-two Belgian divisions and ten Dutch, the equivalent of 400,000 Dutch troops and 650,000 Belgian, if they could be mobilized in time. But neither the Belgians nor the Dutch were in any way equipped to fight a modern war, being deficient in everything from artillery to airplanes, in addition to which they could not begin to mobilize their armies until the Germans attacked them, since Hitler would regard that as a provocation. Gamelin’s plan assumed that it would take several weeks for the Germans to reach the Dyle River, whereas when the time came they would reach it in four days. His view was at once cynical and fatally optimistic: “The Allied advance would be so rapid,” he told Edward Spears, “that the Belgians, even on the most unfavorable hypothesis, would not have time to give way.”

Left unspoken was the fact that after their experience in the First World War the underlying rationale for Plan D was French determination to fight the next war, if it had to be fought at all, beyond the French frontier. The Belgian king and his countrymen were certainly afraid of being invaded by the Germans, but that did not reconcile them to the prospect of France, Britain, and Germany fighting out the war on Belgian soil. The Dutch plan was to flood the dikes and stage a fighting retreat to “Fortress Holland,” the area around Rotterdam, Amsterdam, and The Hague, until the French could link up with them. This too would prove to be a chimera.

The lack of trust in the king of the Belgians in 1939 was sharpened by the shining example of his father, Albert I, who had been the preeminent hero of the First World War, and whose character was that of a preux chevalier, like the legendary “knight in shining armor” in an otherwise sordid tale. When he learned from the Kaiser of Germany’s plan to attack France by crossing Belgium in the event of war, and of the Kaiser’s hope that Belgium would permit the German Army to do so, Albert replied with the courage and dignity he would show throughout his reign: “Belgium is a nation, not a road.”

King Albert I of Belgium.

Small as its army was—less than a tenth the size of the German Army—Belgium had declared war on Germany in 1914 when her territory was infringed, and slowed down the German advance at great cost for over three weeks, making possible the French victory at the Battle of the Marne. The king of the Belgians became an international hero, all the more so since the German occupation of Belgium was by the standards of the time exceptionally cruel; it included such “war crimes,” to use a modern term, as the shooting of over five thousand randomly selected male and female civilian hostages and the wanton destruction of Belgian historical and cultural sites, the most famous of which was the deliberate burning of the great library of the University of Louvain, with its priceless collection of medieval manuscripts and books.

Leopold III lacked his father’s firmness of character, as well as Albert’s ability to govern a small, but volatile and divided, country and win the respect of both the Walloon and the Flemish populations, still today a difficult task. Leopold III was deficient too in many of the qualities demanded of a constitutional monarch, and apt to make sudden and rash decisions on his own.

Some of this unsteadiness communicated itself to the British and the French—Belgium expected them to come to its assistance if it was attacked by the Germans, but in the meantime they were kept in ignorance of the defenses the Belgians were preparing, to such an extent that it was not until March 1940 that a French staff officer was allowed to see them, and then only on the condition that he wore civilian clothes and did not leave his vehicle (the little he did see left him unimpressed). Nevertheless, Gamelin’s Plan D remained the only strategy for the Allies, who persistently overrated Belgian and Dutch powers of resistance.

A more intransigent British commander than Lord Gort might have voiced doubts about Plan D to his own government if not to Gamelin, but this was not part of Gort’s nature. He had won the Victoria Cross not by questioning his orders but by obeying them gallantly despite wounds that would have incapacitated almost any other man.* Gort had his doubts about the ability of the BEF to advance rapidly to the river Dyle, or possibly beyond it to the Albert Canal, in the absence of any knowledge of the Belgian defenses, but he suppressed them gamely in the interests of Allied solidarity.

* * *

The phoney war was not a deliberate stratagem on the part of the Germans—Hitler was infuriated by the maddeningly long delay between his victory over Poland and the attack on France and the Low Countries in May 1940; indeed he had intended to turn on France in 1939 as soon as possible after defeating the Poles. His problem was that he did not like the initial plan for the attack drawn up by the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH, Army High Command).

Hitler has come in for great criticism as an amateur strategist, some of it deserved, but not all. In the first place, he was not without military experience; he had served as a soldier on the western front through some of the worst battles of that, or any other, war and been awarded the Iron Cross First Class for bravery, a decoration rarely awarded to mere lance corporals; in the second, he had a kind of Fingerspitzengefühl, or second sense, about military matters, which at first seemed to demonstrate the truth of Napoleon’s famous remark that “in war, as in prostitution, the amateur is often better than the professional.”

General Franz Halder.

In this case the amateur’s instincts were correct. When Chief of the General Staff of the Army Franz Halder presented to him the first version of Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), the invasion of the Low Countries, it seemed to Hitler merely a less ambitious rehash of the Schlieffen Plan, which had guided the German Army in August 1914, and which led to four years of costly stalemate. The end result, so far as he could see, would very likely lead to another battle on the Somme River, the graveyard of hundreds of thousands of Allied and German soldiers, where Lance-Corporal Hitler had fought in the mud and barbed wire entanglements of the Great War. A military plan of this size, scope, and complexity, drawn up by the most professional and clear-minded general staff in the world, was not something that was easy to dismiss out of hand, but Hitler felt intuitively that it was wrong and sent Halder “back to the drawing board,” as the saying goes.

Halder’s personality was dry and professorial, emphasized by his pince-nez, and that perhaps influenced Hitler as well—he had a horror of being “talked down to” by experts. Halder’s second version of Case Yellow did not please Hitler much either, since it retained the idea of a main attack through Belgium, adding to it secondary attacks to the north and the south, thereby sacrificing the all-important principle of concentration of forces. By now it was October, a full month after the outbreak of war, and the weather had become an issue. The longer the Germans waited, the greater the danger that they would be committed to a winter offensive, and the more time the Allies would have to build up their strength. All the same, Hitler waited, by no means patiently, but at any rate determined not to accept a plan about which he felt to his fingertips uncomfortable, whatever his generals thought. His military instincts had not yet been clouded by too many victories, a taste for gigantism, and the tendency to interfere in tactical battlefield decisions.

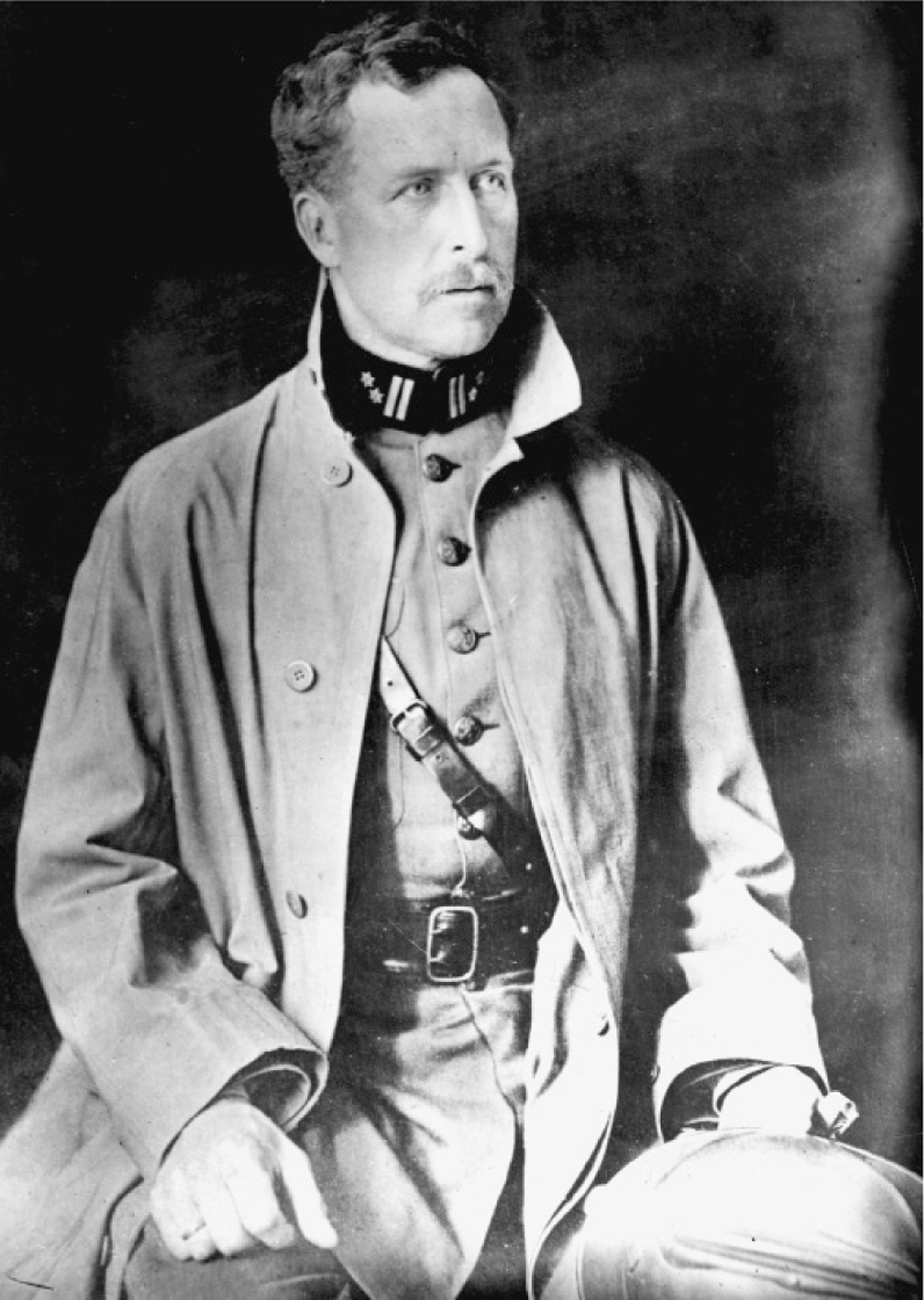

He was not alone in disliking the various iterations of Case Yellow. General Erich von Manstein, the most prominent convert to General Guderian’s ideas about armored warfare, had been moved to the post of chief of staff to the commander of Army Group A, Colonel General Gerd von Rundstedt, whose steely professionalism and forbidding appearance made him perhaps the most respected of the older German generals. Rundstedt too thought that the traditional German strategy going back to the time of Frederick the Great—the swift encirclement of the enemy—was being sacrificed in favor of a frontal attack through northern Belgium and Holland by Army Group B, and that the main attack should be made instead farther to the south, toward Sedan, by Army Group A.

A chance meeting with Guderian led to Manstein’s preparing a series of radically different approaches to Case Yellow, in which not only the main weight of the attack but the bulk of the panzer forces would be aimed at Sedan, and move directly west from there to the English Channel ports, cutting the British and French armies in Belgium off completely. He elaborated this in “a series of memoranda,” which he sent off one after the other to OKH, but even when endorsed with a covering note from Rundstedt they were studiously ignored. His two main points were that “the main weight of our attack must lie with Army Group A, not B,” and that “a surprise attack through the Ardennes . . . was the only possible means of destroying the enemy’s entire northern wing in Belgium preparatory to winning a final victory in France” (Manstein’s italics).

General Gamelin’s belief that the Ardennes were impassable to tanks was contradicted by the observations of many German officers who had spent their leave hiking through the Ardennes with binoculars and Leicas. Manstein’s demands for a complete revision of Case Yellow were outrageously bold, but he persisted. He had anticipated furious resistance from most of the senior German generals, particularly Halder, and he was right.

A further delay was caused by the crash landing in Belgium on January 10, 1940, of a Luftwaffe light aircraft that had gone astray in bad weather carrying a courier with the latest version of Case Yellow. This officer was taken into custody by Belgian policemen before he had a chance to burn the documents completely. Although the charred pages did not contain the actual date of the attack, enough remained legible to cause alarm, somewhat tempered by initial disbelief, in Brussels. From other sources, however, the Belgians heard that the attack was to take place on or around January 14 (the actual date was supposed to be January 17), and they sent a transcript of the material on to Paris.

This incident has become so encrusted with legend that it is hard to sort out fact from fiction. French intelligence suspected that it was a ruse de guerre intended to mislead the Allies about the timing and direction of the German attack, but there is no evidence that this was so—in any case, it was taken seriously by General Gamelin, who hoped that it would encourage the Belgians to open their frontier to the Allied armies, and by the king of the Belgians, who passed a coded warning on to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands by telephone, and to Winston Churchill via their mutual friend Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes.

In the event, after much anxiety in London, Paris, Brussels, and The Hague, nothing happened. A heavy snowstorm made the attack unlikely, and as the various dates passed with no sign that the German Army was about to invade the Low Countries, apprehension gave way to the previous nervous inaction. The Belgian chief of staff, who had rashly ordered the barriers on the Franco-Belgian frontier to be removed, was severely reprimanded, and the king’s determination to keep Belgium strictly neutral (and his hope of riding out the storm without provoking either side) was rekindled.

In Berlin Hitler’s reaction was at first explosive. General Alfred Jodl, chief of staff of the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht), was understandably reluctant to inform the Führer that the plans for Fall Gelb had fallen into the hands of the enemy only a week before the attack was supposed to begin. “Situation catastrophic,” Jodl noted in his diary, surely an understatement, but once Hitler’s initial rage had cooled down a bit, clearer, calmer military minds took over, and it was decided to proceed with the attack as planned.

“What material did they get?” General Halder asks himself sensibly in his diary entry for January 11. “Fueher has reserved decision. Should location of Hq. be changed? What has been divulged: location of Hq., number of armored units, Hq. of 7th Air Division, airfields of Air Group 2?” These are not the questions of a panic-stricken man. In the days to come Halder’s diary merely reflects an orderly reassessment of the attack, and eventually a postponement because of bad weather—the winter of 1939–1940 would be the coldest and harshest in many years, so bad that it would later be seen as an important element in the decline of morale in the French Army.

By January 20, as Halder noted to himself after the day’s Führer conference, Hitler has already accepted a much longer postponement, even to Easter perhaps, and the “Off with his head!” tone of his first reaction gave way to a reasonable enough demand for greater security to prevent an incident like this from occurring again. As the days went by, the capture of the plans no longer seems to have been regarded as catastrophic; indeed for Hitler it may have become a blessing in disguise. He had never liked the plan for Case Yellow, and now he had a good excuse for altering it dramatically.

In the meantime, in order to keep General von Manstein from further tinkering with Fall Gelb, General Halder appointed him to command an army corps in Prussia, the order to take effect on February 9, and accompanied by a promotion that was intended to disguise Halder’s annoyance with him. However, Manstein’s loyal staff—he was already developing a cult following—managed to leak his proposals for changes in the plan to bring them to Hitler’s attention, an “end run” around Halder that succeeded.

Hitler liked what he heard, and invited Manstein to attend a meeting with him on February 17. The Führer had been interested for some time in the idea of making Sedan the Schwerpunkt of the attack, against the advice of his senior generals, who thought this was too risky. Now he was presented with a plan that would put the bulk of his forces in what later came to be called a Sichelschnitt, or “sickel cut,” advancing through the Ardennes, crossing the Meuse, then driving straight on to the English Channel. The attack on the Low Countries would be retained as a kind of huge deception plan, intended to lure the main force of the French Army and the BEF deep into Belgium, where they would be isolated, exposed, and outflanked by the attack on their right, which would swiftly cut them off from the rest of the French Army.

The fact that the Allies already had in their hands the plan for the attack on Belgium and Holland would now work to the advantage of the Germans, a fortuitous example of turning a lemon into lemonade. The Allies would be expecting the German Army to attack the Low Countries, and when it did they would not be looking toward the Ardennes, where the real blow would come. Almost as important, the tanks would be used the way Guderian (and Liddell Hart) thought they should be used: punching holes in the enemy line through which the slower-moving infantry would march.

Fall Gelb was ambitious and conceived on an enormous scale, involving nearly three and a half million men, over three thousand tanks and three thousand aircraft. In the aftermath, it would be described as a blitzkrieg, and the German victory attributed to superior mechanization, but this is a false picture of what was to come. The bulk of the German infantry marched on foot just as it had in 1914, and there were still over half a million horses in the German Army in 1940. Most of the artillery was horse drawn, company commanders rode ahead of their men, while farriers and cobblers, mainly in horse-drawn wagons, moved behind the troops to keep men and horses shod. By comparison, the British Army, though small and poorly provided with tanks, was almost completely motorized. Of course neither the French nor the British (still less the Belgians and Dutch) were equipped or prepared for long marches, since from the beginning they had intended to fight a defensive battle. The Germans, on the other hand, would have long distances to cover, and commanders worried, not without reason, about the gap that would open up between the fast-moving panzer divisions and the much slower infantry divisions behind them.

At first Halder did his best to sabotage Manstein’s plan by surreptitiously detaching armored divisions from Army Group A, but he eventually came around to the Manstein plan, partly because it was a daring gamble that promised decisive results, whereas what he feared most was that a longer, slower “conventional” campaign might fail, or bog down into static warfare like the previous war. His diaries reflect the immense complexities of the plan, as well as Hitler’s growing obsession with the details, and his tendency to ask for the transfer of whole corps and armies without giving any thought to the logistics involved, the mark of an amateur.

Over lunch Manstein found Hitler “surprisingly quick to grasp the points which our Army Group had been advocating for many months past.” Even more to his surprise, Hitler approved the new plan, and it was put into immediate effect, though without Manstein, who had been deftly shifted to the sidelines by his superiors. Manstein concluded that “Hitler had a certain instinct for operational problems, but lacked the thorough training of a military commander,” a portent of things to come, but in the meantime, the plan that Manstein and Guderian had worked out in such detail would emerge as the final version of Case Yellow, while the Allies still clung to the belief that the main focus of the coming attack would be in Belgium, on the Dyle River, and that their best chance for victory was to get there in full strength before the Germans did.

_________________________

* The Victoria Cross is so rarely given that only 1,358 have been awarded since it was instituted by Queen Victoria in 1856.