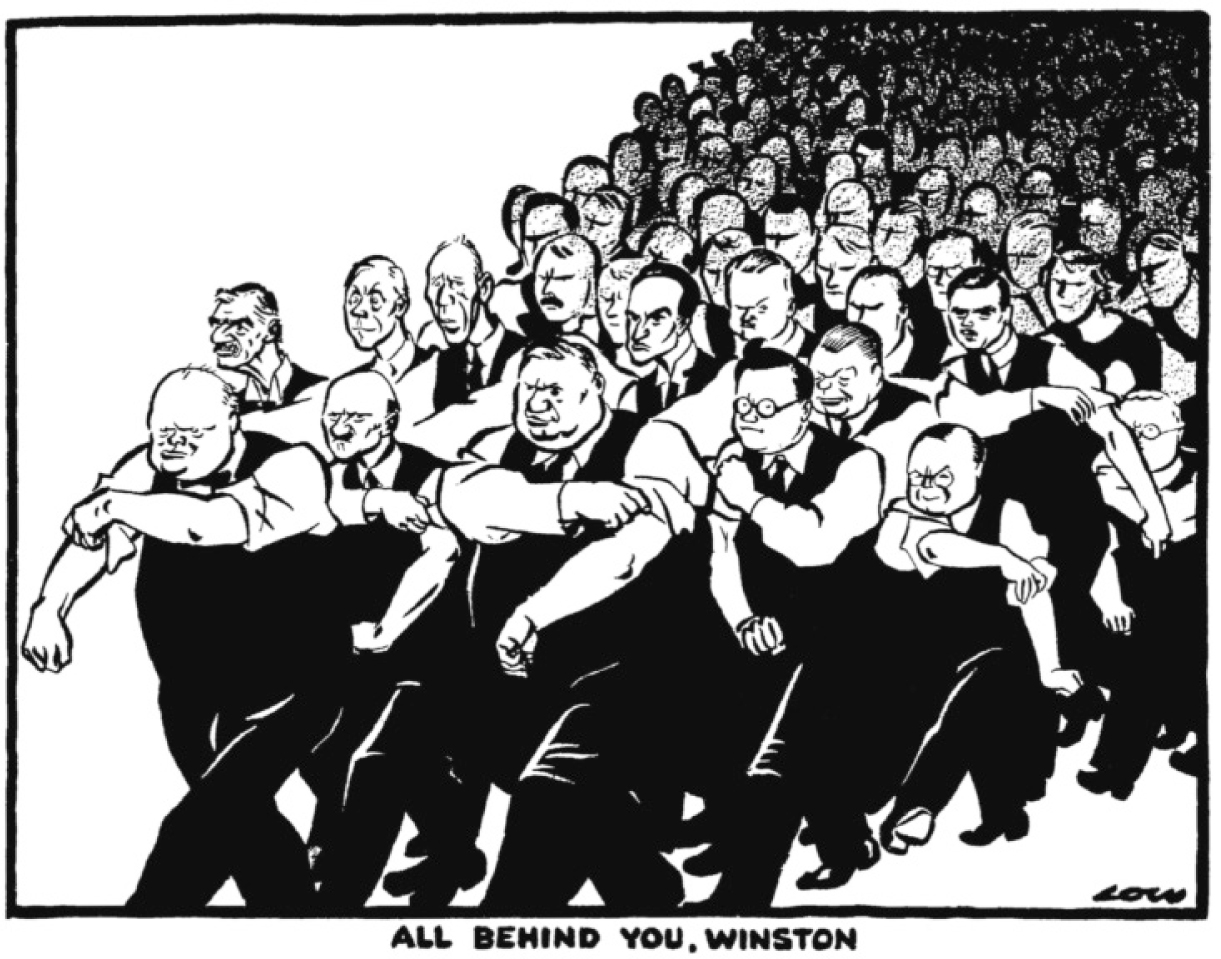

IT HAD TAKEN Churchill forty-one years in politics to “climb to the top of the greasy pole,” in Disraeli’s famous words. The office of prime minister had eluded his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, and until May 9, 1940, seemed likely to elude the son. Nobody ever came to that high office with a heavier baggage of lost causes, political misjudgments, and missed opportunities, but his accession to power was notably free from political vindictiveness. The only person to suffer was Sir Horace Wilson, Chamberlain’s high priest of appeasement, perhaps the most influential éminence grise in British political life since Cardinal Wolseley. Sir Horace arrived in his office next to that of the prime minister at 10 Downing Street on the morning of May 11 to find Lord Beaverbrook and Brendan Bracken waiting for him grimly as he hung up his umbrella and hat. He quietly packed the few personal belongings from his desk into his briefcase and left to return to the humdrum job of overseeing the civil service and promoting the purchase of savings certificates. His office was taken over immediately by Bracken in his new role as the prime minister’s parliamentary private secretary.

Churchill was that rarest of politicians—he never forgot a friend or a supporter. Anthony Eden became secretary of state for war, Duff Cooper, who had resigned his place in the cabinet in protest over Munich, became minister of information, Harold Nicolson became parliamentary secretary to the Ministry of Information (in effect, Cooper’s number two). Brendan Bracken and Lord Beaverbrook were made privy councilors over the strong objection of the king. Churchill’s generosity of spirit even impelled him to let Mr. and Mrs. Chamberlain continue living in 10 Downing Street until they had time to move out while the Churchills continued to live in the more cramped but gilded splendor of the first lord’s flat in the Admiralty. He retained Chamberlain in the War Cabinet as lord president of the council (an ancient, but by now honorific office) and more important as leader of the Conservative Party, and Lord Halifax as foreign secretary.

He did not forget my uncle Alex, either. Alex was one of that small group of wealthy loyalists who had helped keep the Churchill ship afloat during the years when he was out of office (these included the South African financier Sir Henry Strakosch and Lord Beaverbrook) and was one of the few strong critics of Nazi Germany and the policy of appeasement. Alex cannot have hoped to reap any benefit from Churchill in 1934 when he hired him to serve as an adviser on historical films at £4,000 a year, no small sum at the time.* Churchill was then in the political wilderness, with few prospects of escaping from it, and saddled with a life style that soared well beyond his income. No doubt Alex admired his historical knowledge, but that alone would not explain his commissioning Churchill to write a screen treatment for a life of King George V for the then astronomical sum of £10,000, or his purchase of the screen rights of several of Churchill’s books for inflated sums.

In any event the two men acquired a respect for each other that went beyond a much needed source of income for Churchill. When Alex acquired the film rights to T. E. Lawrence’s Revolt in the Desert (Lawrence described Alex as “unexpectedly sensitive,” and surprisingly sympathetic to Lawrence’s desire that no film be made about him during his lifetime), Churchill was diligent in making suggestions about the screenplay, and even wrote dialogue for it that found its way into the script of David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia twenty-five years later, as well as for That Hamilton Woman in 1941, in which several of the patriotic passages in the screenplay have the unmistakable ring of Churchill’s prose. Alex also provided those in the shadowy world of the British intelligence services who shared Churchill’s view of Nazi Germany with contacts throughout Europe, and in the United States—he would even hire two of Churchill’s daughters, Diana and Sara, to work for London Films and would probably have hired Churchill’s rambunctious son too had Randolph been employable. Through whatever chemistry, the two men liked each other. Alex never forgot that Churchill’s was the first, the strongest, and the most consistent voice against Hitler; Churchill never forgot Alex’s generous (and supremely tactful) support.

They shared a tolerant view of the world and a lack of prejudice—Churchill himself, after all, was half American, Strakosch was born an Austrian Jew, Beaverbrook was a Canadian, Bracken an Irishman masquerading as English or Australian according to his whim, Alex an anglicized Hungarian Jew—as well as a love of fine food, good cigars, champagne, brandy, and the south of France, and a taste for the luxurious life whether they could afford it or not. They also had in common a belief that Hitler and Nazi Germany were evil and must be defeated long before most other people had begun to come to that conclusion.

In May 1940 that was still being resisted by many people, including that apostle of appeasement and last-ditch Chamberlain loyalist, the United States ambassador to the Court of Saint James, Joseph P. Kennedy, father of President John F. Kennedy, who noted pessimistically in his diary on May 10 the “definite undercurrent of despair” in England, his concern that Churchill was a drunk, his belief that “the affairs of Great Britain might be in the hands of the most dynamic individual in Great Britain, but certainly not in the hands of the best judgment in Great Britain,” and predicted in a letter to his wife, Rose, “a dictated peace with Hitler probably getting the British Navy.”

Alex had already made Britain’s first full-length feature propaganda film, The Lion Has Wings, at Churchill’s request, with Ralph Richardson playing an RAF wing commander† and Auntie Merle his wife (Merle Oberon was not particularly convincing in the role of an RAF officer’s wife, but Alex needed a star for the film at once). It had been necessary to halt work on Alex’s other film projects to make The Lion Has Wings quickly, but both Alex and Churchill recognized that in the long run overt propaganda like this was not going to dismay the Germans or impress the United States and other neutral countries. The vital element was to produce ambitious British films that could succeed on their own in America, beating the Hollywood studios at their own game, and demonstrating that the British film industry, like Britain herself, was still alive and kicking. The aim was to convince people not that the morale of British bomber squadrons was high, as The Lion Has Wings tried to do on the cheap, but that Britain, and the British way of life, was worth defending and had many things in common with the United States—unlike Nazi Germany, whose propaganda films were boastful and militaristic, and never played in American movie theaters, not because they were banned but because nobody wanted to watch them. The best thing Alex could do for Britain was to complete The Thief of Baghdad and Jungle Book, and make That Hamilton Woman even if it meant making them in Hollywood with the connivance and support of the British government.

Merle Oberon and Ralph Richardson in The Lion Has Wings.

The Korda family being the kind of top-to-bottom authoritarian structure it was, none of this was revealed to us at the time. In any case, even at my age I was aware that much bigger events were taking place at the time that absorbed everybody’s attention.

The news that the long-anticipated German attack on the west had begun on May 10 was doggedly optimistic, and in retrospect clearly filtered through layers of censorship and the Ministry of Information. The Times reported with exceptional restraint the laconic communiqué from Gamelin’s Grand Quartier Général that fighting was taking place “on a large front, and the enemy was everywhere repulsed.”

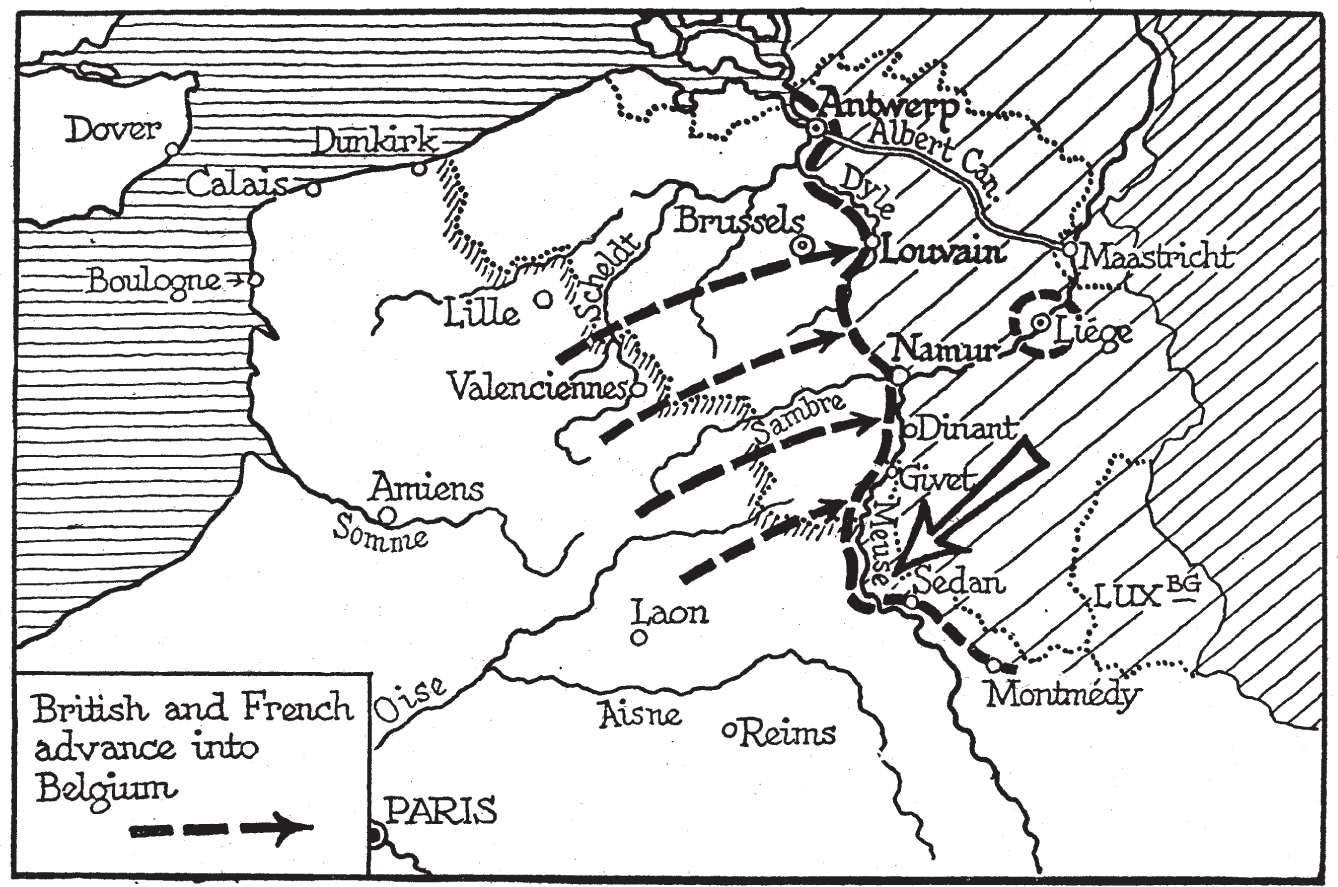

This piece of wishful thinking was followed shortly by the news that the Belgians had—at last—“opened the red and white poles spanning the roads near the Belgian Customs houses” and appealed for the assistance of the French Army and the BEF. In keeping with Hitler’s usual ruthlessness the Dutch, the Belgians, and the Luxembourgers had been attacked without any warning or declaration of war—they were woken before dawn by the sound of bombing, artillery fire, tank engines, and aircraft dropping parachute troops. British soldiers entering Belgium were greeted “with an enthusiastic reception from the population” who decorated their vehicles and guns with flowers. Girls kissed the British soldiers, men handed them bottles of beer, snacks, and chocolates, “wherever we went through a village our welcome was rapturous,” recalled an officer of the East Surrey Regiment.

By all accounts General Gamelin was calm and content; Plan D was being carried out exactly as he had conceived it. French armies and the BEF were advancing into Belgium on schedule. At the sharp end of the stick there was slightly more concern. “News at present is sketchy,” wrote Lieutenant-General Pownall, Lord Gort’s chief of staff on May 10, “but we know that Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg are attacked. . . .” He concluded with a trace of philosophy unusual for a general, “A lovely May day. To think the human race should spend it in this folly.”

The British 12th Lancers, unhorsed and transformed into an armored car regiment, were first across the Belgian frontier and crossed without difficulty the Escaut and the Dendre rivers, the bridges of which General Pownall had supposed would be blown up by saboteurs or parachutists. The 12th Lancers reached the Dyle River in central Belgium, on the evening of May 10, their advance slowed down only by the crowds of civilians lining the roads to cheer them.

The Dyle River, once the British reached it, turned out to be something of a disappointment, “little more than a wide stream,” as the British Official Military History of the Second World War puts it, and disconcertingly shallow, certainly not to all appearances a serious obstacle for the German Army. By the evening of May 10 news was already coming in that caused more concern at General Gort’s headquarters, which was being moved east from village to village as he followed his army.

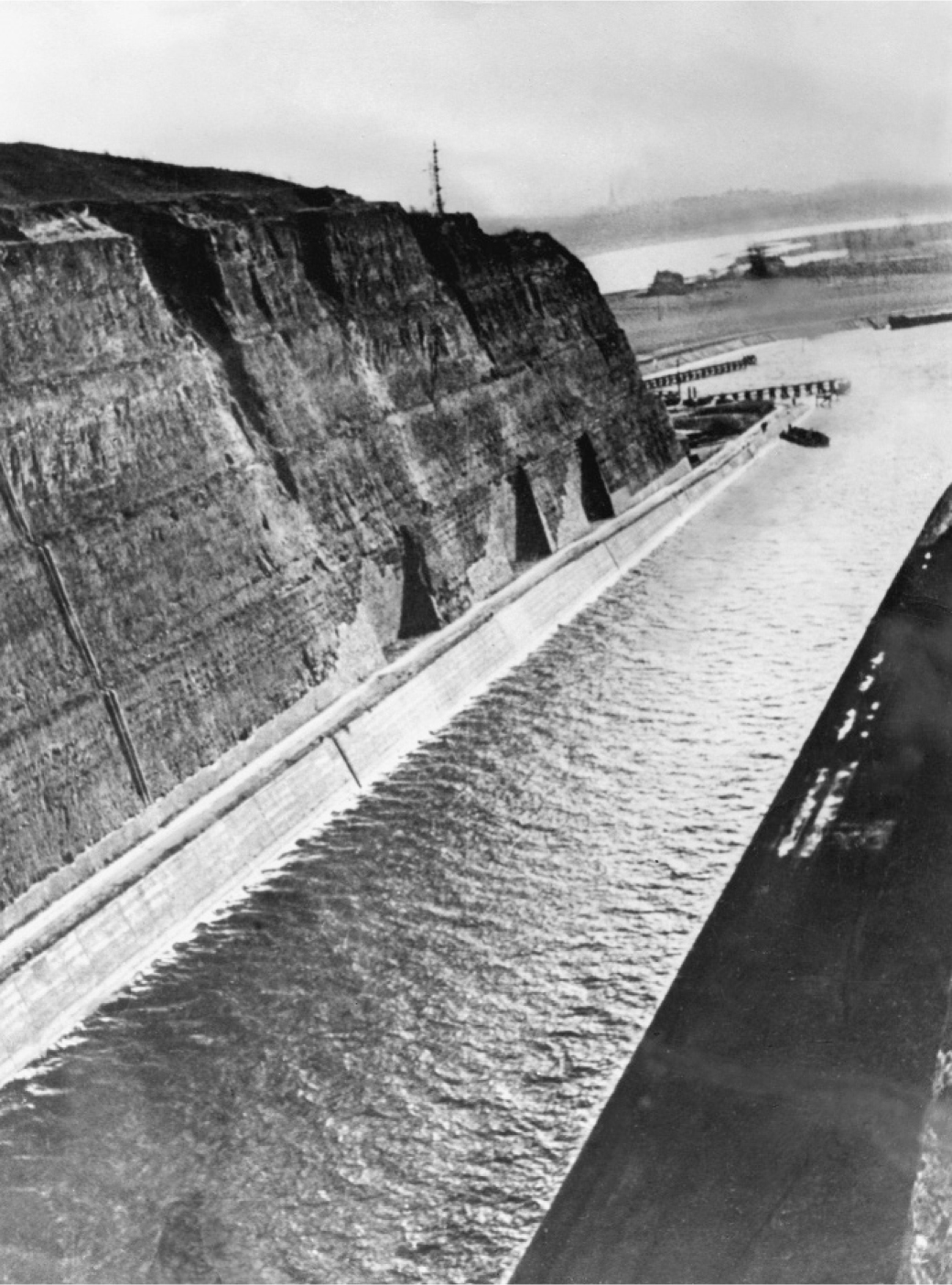

German sappers building a bridge across the Meuse, May 1940.

Fort Eben-Emael and the Albert Canal.

In a daring move, a dawn attack by German gliders and parachute troops had succeeded in securing two vital bridges over the Meuse at Maastricht, in southern Holland, which the Belgians were supposed to have destroyed, as well the enormous fort of Eben Emael, Belgium’s equivalent to the Maginot Line, which was supposed to guard both the bridges over the Meuse and those over the nearby Albert Canal, and which was to have been Belgium’s first line of defense. German armor was “pouring through the hole,” and the Belgian Army, which was still in the process of mobilizing, was already in retreat. “Trust the Belgians to bog it,”‡ General Pownall commented sourly, less philosophical now.

An altogether different mood reigned at the Felsennest, Hitler’s forward headquarters in the Eifel Mountains, near the Belgian border, where the Führer had gone to observe the battle. As the day ended, Hitler breathed a sigh of relief, despite a sleepless night and a good deal of anxiety. He would later exclaim, “I could have wept for joy; they’d fallen into the trap!”

His generals were more cautious—“Very good marching achievements,” was the most Halder would concede for the day—but Hitler was right. He had gambled that the French and British would advance as deeply and as quickly as possible into central Belgium and Holland with their strongest units, while to the south of them General von Kleist’s panzer divisions were driving west at top speed toward the Meuse, under the canopy of the Ardennes Forest.

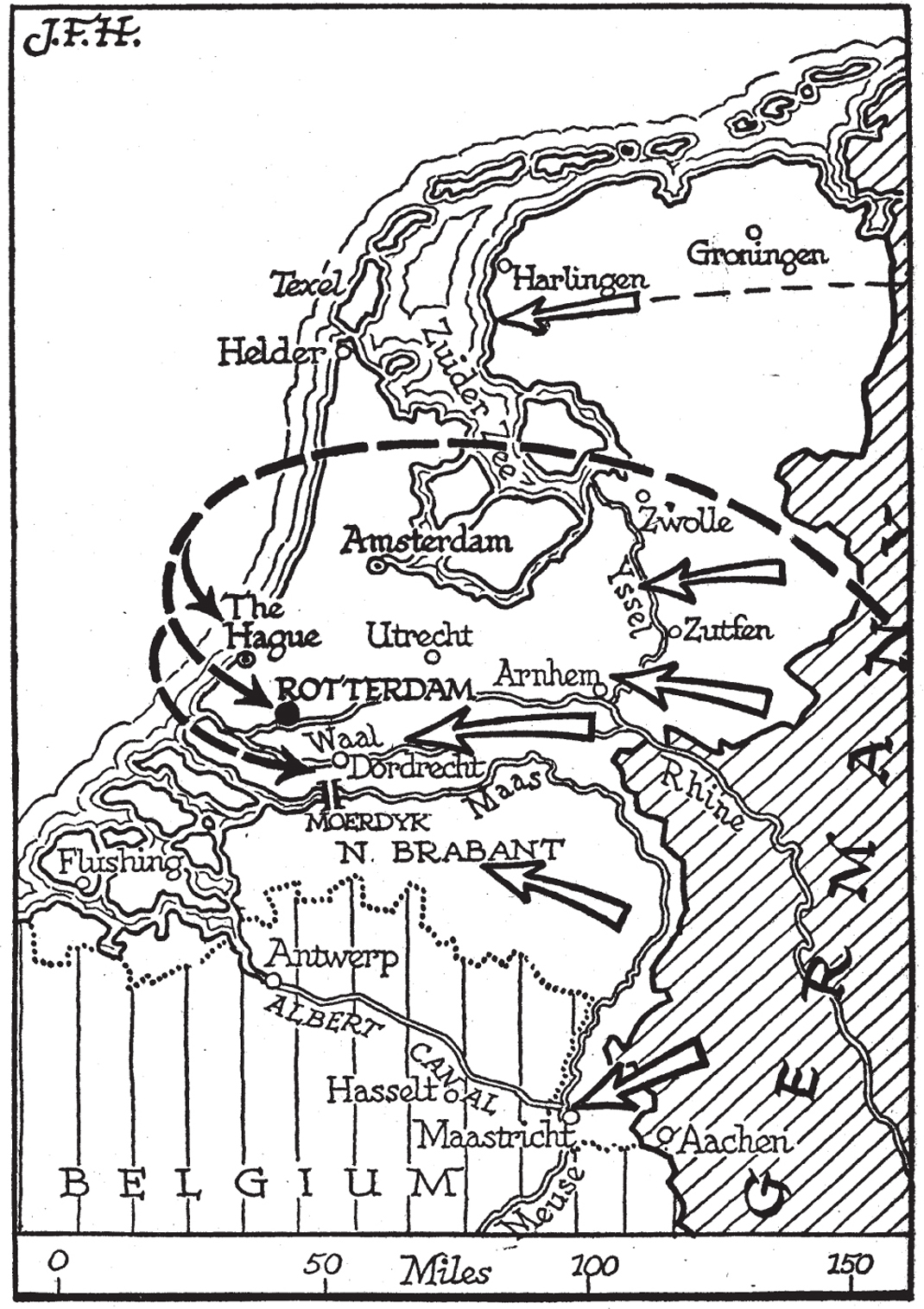

The next day it was beautiful weather again. Hitler paused to enjoy the birds singing all around him in the woods at the Felsennest, but farther to the west there was a mood of sharply increasing anxiety among the Allies. To the north, the Dutch Army, still in the process of mobilization, was unable to slow the German advance, most of the aircraft of the Belgian and Dutch air forces had been destroyed on the ground by the initial German air attacks, and now the roads were beginning to fill with terrified civilian refugees fleeing the fighting, and slowing down the advance of the French and British armies to their lines.

The Luftwaffe attacked the refugees mercilessly to increase the confusion on the ground. A British private of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment, would later write,

As we were moving forward, there were thousands of refugees around. I remember going down this long straight road with fields on either side. [It] was filled with children, old people, horses and carts, prams, wheelbarrows, donkeys, anything that would carry a load. We had to take to the fields on either side. The bombers came along and bombed this column of refugees, and the Messerschmitts came behind and machine-gunned them. We were all right because we were in the flanks in the field—but at that time they didn’t bother about us. . . . We saw people and horses and carts blown sky high. It was terrible. I remember seeing people mutilated, blown to pieces. . . . We could do something about the animals. We saw a horse that had its guts blown open, and we could shoot it. But there was nothing we could do about the human beings. We couldn’t stop and give first aid. . . . It was just murder. . . . I still dream about it.

A more threatening problem than the refugees was a request from the Belgian government for the BEF to stop using the roads through the suburbs of Brussels for the passage of British troops at once, since the king had just declared it an “open city” to prevent its being bombed or fought over. Undoubtedly the king was alarmed by the news of heavy German bombing of Dutch towns, and was just as anxious to spare Brussels as the French government was to spare Paris, but it was not a good start to an alliance. The king’s decision led to a high-level conference at the Château Casteau the next day to straighten out the misunderstandings between the French, British, and Belgian armies. Unfortunately, General Lord Gort missed the conference—as usual, he wanted to be up front with his troops, rather than in his headquarters—so Lieutenant-General Pownall substituted for him, which was probably just as well since Pownall was a particularly sharp and accurate observer. This was a kind of “summit meeting,” to use the modern phrase, attended by His Majesty the King of the Belgians, M. Daladier, now the French war minister, General Georges, commander of the northeast front, General Gaston Billotte, commander of the French 1st Army Group, and a full cast of lesser generals and aides. King Leopold III was accompanied by his military adviser General van Overstraeten, whose influence on the king everybody agreed was unfortunate, since Van Overstraeten was servile, militarily incompetent, and defeatist. “A little too suave, glib and specious . . . more of a courtier than a soldier,” Pownall commented.

Although the king had been educated at Eton, he did not make a good impression on the British. He was slender, handsome, and coldly polite, but his face exhibited none of his father’s strength, and in photographs he looks spoiled and impatient rather than regal. To Pownall he also seemed “pretty dazed,” and it was left to Van Overstraeten to explain the loss of the Meuse bridges at Maastricht, the Belgian attempt to hold a position east of the Dyle River instead of linking up with the BEF and the French First and Seventh Armies and the king’s decision to declare Brussels an open city without consulting his allies. General Georges seems to have been his usual charming self, but distracted, perhaps because as the man in command of the entire French front from Switzerland to the Channel he was already aware that German armored forces in unprecedented numbers were making their way through the supposedly impassible Ardennes with little or no opposition.

Georges had never had any faith in Gamelin or his ideas, and now his worst fears about Plan D were coming true. In any event, he brought the conference to a close with two conclusions, the first of which was to recur again and again over the next six weeks: that the Royal Air Force should provide more fighter squadrons immediately—lack of British fighter aircraft would shortly become the French (and Belgian) explanation for every failure on the ground.

The second was General Georges’s admission that he could no longer hope to coordinate three separate national armies in battle from his own headquarters at La Ferté—doubtless Georges was already beginning to sense that the decisive battle would not be fought here in Belgium, but farther south at Sedan when the Germans emerged from the Ardennes. His attention would be required there, so he proposed that General Billotte undertake the task of coordinating the three armies in Belgium on his behalf.

This was a fatal mistake. Billotte was sixty-four years old, already overwhelmed by the responsibility of commanding 1st Army Group, and by no stretch of the imagination an inspired or inspiring leader for a coalition—when he returned to his headquarters he is said to have burst into tears in front of his own staff at the immensity of the task and his incapacity to perform it. Even the normally unshockable General Gamelin was surprised by this decision when news of it reached Vincennes—he referred to it as “an abdication” on General Georges’s part.

In any case, everybody at the conference agreed to the proposal, including General Pownall on behalf of the absent Lord Gort, although it meant that the BEF would now be receiving its orders passed from Gamelin’s GQG in Vincennes to Georges’s HQ at La Ferté, and from there to Billotte’s HQ. As if this were not already complicated enough, in a further attempt to isolate himself from General Georges, General Gamelin had set up at Montry, halfway between Vincennes and La Ferté, a headquarters to act as a kind of way station between himself and Georges. Given the fact that there was no radio at Vincennes, and that the telephone system in Holland and Belgium was swiftly collapsing as the Germans advanced (the crowds of refugees on the road doubtless contained any number of switchboard operators and linesmen), it is difficult to estimate how long it might take for an order to reach the hapless Billotte as his headquarters moved from place to place in the ebb and flow of battle, or how long it would take for him to contact General Gort or the king of the Belgians, even if he tried.

There was a further problem that haunted General Georges. General Gamelin had long ago insisted that a French army should be placed in the north to hold Antwerp and advance to Breda in support of the Dutch the moment the battle began. General Henri Giraud’s powerful Seventh Army was poised to do this, despite vigorous protests from Georges and Giraud from the very beginning. Gamelin might be uncommunicative and his GQG as hard to make contact with as the Forbidden City in Beijing (Paul Reynaud said Gamelin would have made a better bishop than a soldier), but he was still commander in chief, and he clung stubbornly to the idea of keeping an army in the north; indeed it was a vital element of Plan D.

Left unsaid was the fact that General Giraud’s Seventh Army also comprised the French Army’s strategic reserve. If the Germans did succeed in piercing the Allied line, it would be up to the Seventh Army “to plug the gap,” although how it was to get there from Antwerp while under attack was unclear to everyone except Gamelin and his staff, which specialized in just such ambitious and closely detailed projets, or what might be called in English “speculative plans.”

Plan D was in any case built on a certain degree of speculation—nobody had guessed how quickly the Germans could move, or had learned the lessons of the German attack on Poland. General Gort, for example, thought it would take the Germans two or three weeks to reach the Dyle River, whereas they did it in four days, and General Gamelin assumed that if the Germans were foolish enough to advance through the Ardennes it would take them weeks to cross it. In fact, the Germans would reach Sedan in two days, and by the evening of May 12 they were already in sight of the Meuse River.

By the thirteenth General Pownall was complaining that the king of the Belgians was in a panic (“seems completely to have lost his head”) and was ordering bridges destroyed before French troops had crossed them. “What an ally!” Pownall confided to his diary.

But the next day was to produce a crisis bigger than anyone could have imagined, one that would seal the fate not only of the BEF but of France.

_________________________

* That was the equivalent then of $20,000 a year, with the purchasing power of at least $300,000 today, allowing for inflation.

† Richardson was an enthusiastic amateur pilot, and joined the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm as a pilot, as Olivier would also do until Churchill urged them to leave the Royal Navy and resume acting.

‡ This is the polite British equivalent of “fuck it up.”