Major General Erwin Rommel, center, with his staff, after crossing the Meuse.

Major General Erwin Rommel, center, with his staff, after crossing the Meuse.

“DEAREST LU,” Major General Erwin Rommel wrote his wife on May 9. “You’ll get all of the news for the next few days from the papers. Don’t worry yourself. Everything will go all right.”

Rommel was an infantryman, who had only taken command of the 7th Panzer Division on the Rhine in February 1940. The author of a respected and bestselling book on infantry tactics, Infanterie greift an (Infantry Attacks when it was eventually published in English), that sold over half a million copies in Germany, and attracted Hitler’s attention, Rommel had no previous experience with tanks.

Hitler’s appreciation of the book led to Rommel’s appointment in 1938 as the commander of Hitler’s military bodyguard battalion, a largely ceremonial army unit—the serious work of protecting the Führer was carried out by the hardened professionals of the SS Reichssicherheitsdienst. The army bodyguard battalion was spit-and-polish soldiering instead of the real thing, and although it eventually won Rommel promotion from the rank of lieutenant colonel to that of major general, he was not happy among the overbearing Nazi politicians in Hitler’s entourage: he clashed at once with Baldur von Schirach, leader of the Hitler Youth, and quickly earned the enmity of Hitler’s powerful personal secretary Martin Bormann. Politics had in any case played no part in his selection: Rommel was not a Nazi, he was a superbly trained professional soldier, a war hero—as a lieutenant in World War One he won the Pour le Mérite, the Imperial German Army’s equivalent of Britain’s Victoria Cross or America’s Medal of Honor when awarded to a junior officer—and perhaps more important he was not a Prussian, did not bear a “von” in front of his name or wear a monocle; it was thought that the Führer might therefore get along well with him, and so it proved. It did not hurt that he was actually slightly shorter than the Führer.

Rommel.

Baldur von Schirach, center, leader of the Hitler Youth, with the Führer.

Rommel, however, got no chance to see combat in Poland, where he was basically a combination of spectator and military tour guide for the Führer, but afterwards he asked Hitler to give him command of a panzer division so that he could get back into action again. Hitler liked and respected Rommel as a soldier, and agreed with some reluctance to let him go, thus setting Rommel on the path to a military career that would place him among the world’s great captains.

The 7th Panzer was still in the process of transforming itself from a “light division”* into an armored division when Rommel took command—it had fewer tank battalions and more motorized infantry battalions than the older panzer divisions, and was equipped with a mix of tanks, almost half of which were Czech 38(t) tanks taken over by the German Army after Hitler seized Czechoslovakia.

Rommel seems to have understood instantly that what was needed was to apply to tanks the same tactics that had worked so well for him as an infantry leader: a combination of boldness, speed, and the aggressive use of firepower. Swift raids, the element of surprise, and long, unexpected flank attacks were his specialties; indeed his generalship resembled in many ways that of Stonewall Jackson, and like Jackson Rommel “led from the front,” setting an example of indifference to danger for his men at every opportunity. He was a natural leader, one of those rare individuals who remain perfectly cool under fire and always seem to know what to do in the confusion of battle—it is hard to think of any general on either side in World War Two in whom his men had more absolute confidence.

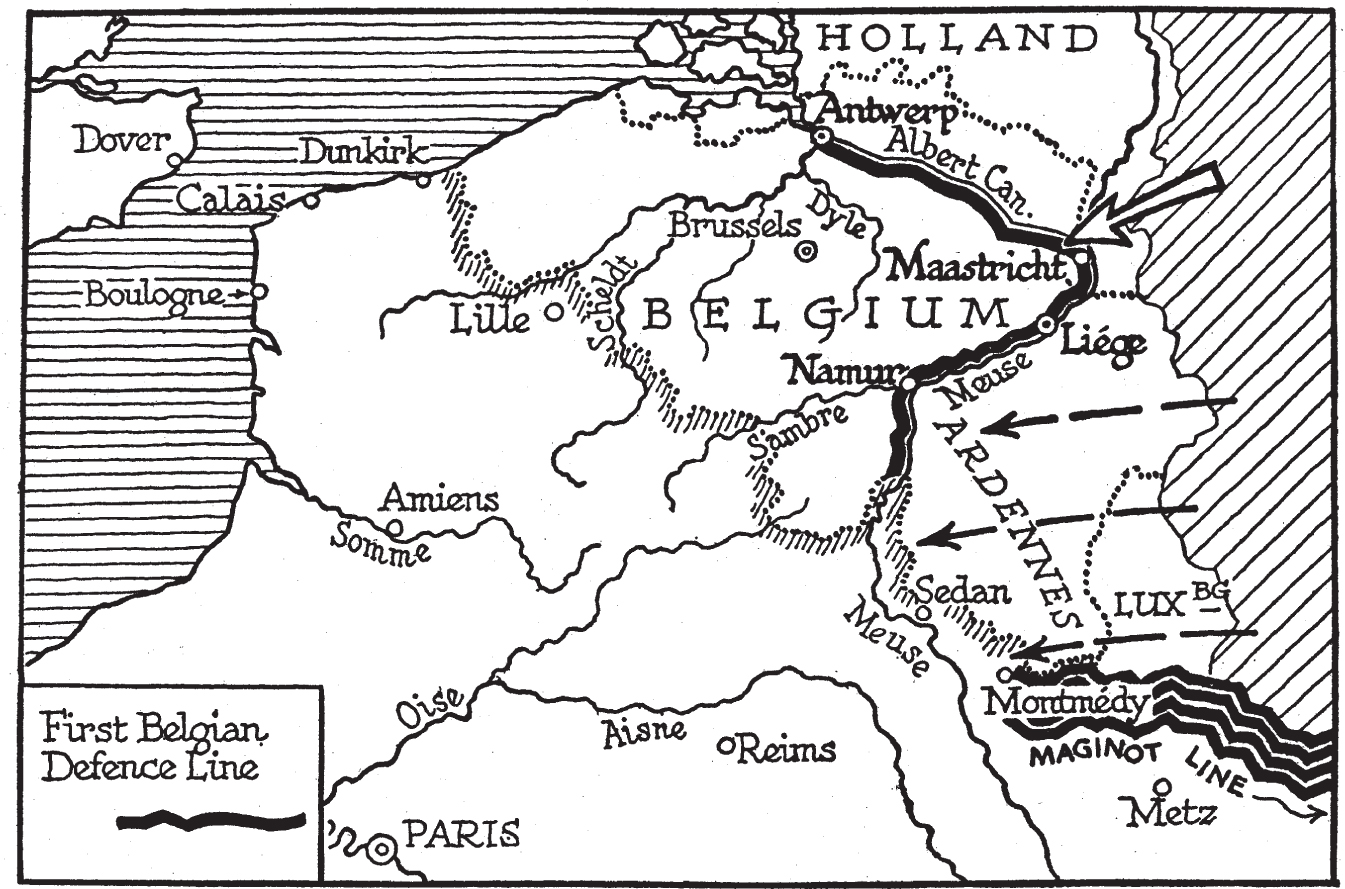

Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division was part of Lieutenant General Hermann Hoth’s XV Panzer Corps, intended to protect the right flank of the main attack by Guderian’s much more powerful XIX Panzer Corps toward Sedan—it would have been essentially a sideshow, had it not been for the astonishing speed of Rommel’s advance. His division motored peacefully through Luxembourg, then separated into two columns and plunged into the Ardennes Forest only to find that the Belgian Chasseurs Ardennais had already barricaded forest tracks and blown up the roads to slow down the German advance. Most of the lightly armed Chasseurs Ardennais had then been withdrawn over the Meuse or were ordered north to reinforce the forces defending the Belgian heartland, and Rommel simply blew away those who remained.

A German military policeman guides traffic toward Sedan, May 1940.

Nobody understood better than Rommel B. H. Liddell Hart’s admonition that an undefended obstacle is quickly overcome. Faced with an obstruction he moved his tanks off the roads into the fields and woods, drove his combat engineers on to perform miracles of road repair and bridging, and kept up the swift pace of his advance, shouting to everyone, “Tempo, tempo, tempo!” (Perhaps best translated as “Get on with it!” or “Hurry up!”)

French armored and horsed cavalry, intended to make contact with the enemy, was slow coming up, hampered partly by the demolition work of those same Chasseurs Ardennais, and was unprepared for Rommel’s boldness, which would soon become legendary. His columns were led not by horsemen, like the French, but by motorcyclists riding at high speed over rough ground with a machine gunner in the sidecar who opened fire at the first sight of the enemy. His troops were taught never to halt and take cover, but to keep moving at all costs and “spray” fire at the enemy, in keeping with Rommel’s belief that “the day goes to the side that is the first to plaster its opponent with fire. . . . It is fundamentally wrong to simply halt and look for cover without opening fire,” he wrote, “or to wait for more forces to come up and take part in the action.”

He himself set a perfect example of the German principle of Auftragstaktik, setting a goal for his units rather than issuing binding step-by-step orders, thus leaving it for junior officers and even NCOs to devise their own means of accomplishing their goal, and relying on the lavish use of superior German firepower to force the enemy back.

The French reconnaissance forces, an unwieldy and outdated mix of light armor and horsed cavalry, were overwhelmed and forced back into what Rommel described as a “hasty” retreat. “I’ve come up for breath for the first time today,” he wrote to his wife, Lucia, on May 11. “Everything wonderful so far. Am way ahead of my neighbors. I’m completely hoarse from orders and shouting. Had a bare three hours sleep and an occasional meal. . . . Make do with this, please, I’m too tired for more.”

What it was like to be faced with a German panzer division on May 11 was described by a French officer as the remains of his division emerged from the woods near the Meuse: “Towards midday, groups of unsaddled horses returned, followed on foot by several wounded cavalrymen who had been bandaged as well as possible; others held themselves in the saddle by a miracle for the honour of being cavalrymen. The saddles and the harnesses were all covered with blood. Most of the animals limped; others, badly wounded, just got as far as us in order to die, at the end of their strength; others had to be shot to bring an end to their sufferings. . . .”

By 4 p.m. on May 12, only two days after the beginning of Fall Gelb, what remained of the French defenders of the Ardennes had crossed to the west bank of the Meuse, then destroyed the bridges behind them, just in time. The Meuse is about 120 yards wide at this point, a landscape suitable for a painting by Monet, but a formidable military obstacle. Rommel reached it between Dinant and Houx just as the last bridge in front of him was blown up, but late that night his men discovered “an ancient weir” connecting the east bank of the Meuse at Houx to a small, heavily wooded island midstream. In the dark some of his dismounted motorcyclists managed to tiptoe precariously across the slippery stones to the narrow island.† On its far side they found a rusty lock gate that enabled them to cross to the west bank of the Meuse one by one, and establish a small, beleaguered bridgehead there, slightly covered by a road and the railroad that ran along the west bank of the river.

By dawn on May 13 the unthinkable had happened, German panzer troops had not only traversed the supposedly “impénétrable” Ardennes in fifty-six hours but had crossed the Meuse River, the major “natural obstacle” between there and Paris—or the English Channel.

Guderian’s panzer divisions, the main blow, were already approaching Sedan, but Rommel was the first to cross the Meuse, as he must surely have hoped for from the start.

Rommel spent the day of May 13 in constant action. The French had at last woken up to what was happening, and Rommel’s attempts to get his men across the Meuse at several points in inflatable rubber boats were met with fierce small arms fire and constant artillery shelling. A smoke screen might have been useful, but he had no smoke unit, so as a substitute he ordered his men to set fire to the houses nearest the river, the normally placid surface of which was whipped into a white froth by rifle and machine-gun fire. A German soldier described it as looking like the head in a stein of beer; a French soldier described it, not surprisingly, as looking like the froth in a glass of champagne. Rommel saw “a damaged rubber boat [come] drifting down to us with a badly wounded man clinging to it, shouting and screaming for help—the poor fellow near to drowning,” but there was nothing to be done for him. Rommel’s casualties were mounting up rapidly, and many of the rubber boats were damaged or sunk. A few of Rommel’s tanks had come up by then, so he ordered them to drive up and down the east bank firing directly across the river at the French emplacements on the west bank. Rommel at this point took over command of one of his own rifle battalions, got the river crossing going again under intense fire, crossed over to the opposite bank in the first boat, “and organized the fresh effort, in which he himself took the lead.” Then he went back across the river and drove north to supervise another fiercely contested crossing, found a company of engineers trying to build a bridge across the Meuse with 8-ton pontoons, “stopped them and told them to build the 16-ton type,” and as soon as the bridge was ready he was the first over it in his “8-wheeled signal vehicle” despite heavy shelling. In Rommel’s own words, the situation “was looking decidedly unhealthy” on the west bank, where a strong French counterattack was taking place. The commander of the 7th Motorcycle Battalion and his adjutant had both been killed, so Rommel took over personally, organized the remaining troops to resist it—like that of all great generals, his display of courage, calm, and optimism was infectious—then left his vehicle where it was and returned once more to the east bank on foot to give orders for ferrying a few of his tanks across that night. He had established a small, insecure bridgehead, but a bridgehead all the same.

Even without his tanks, however, the news of Rommel’s river crossing on May 13 caused consternation all the way up the Allied chain of command.

Sluggish and poorly planned communications prevented the news of Rommel’s crossing of the Meuse from reaching General Gamelin in his ivory tower at Vincennes until lunchtime on May 13. First reports produced “a lively emotion” even in those hushed surroundings where the luncheon hour was sacred, and Gamelin actually roused himself to place two calls to the chief of staff of the Ninth Army, who replied calmly that everything was under control and that “the incident at Houx was in hand.”

Gamelin and his staff were busy dealing with what must have seemed more serious problems. The Dutch were on the brink of surrendering, the king of the Belgians was in a panic, the full force of the German attack toward the Dyle River was beginning to be felt; it was not until half past nine that night that General Georges, for once placing a direct call to General Gamelin despite their scarcely being on speaking terms, revealed that there had been “un pépin assez sérieux” (a rather serious pinprick) on the Meuse.

This was putting it mildly. While Rommel was consolidating his bridgehead, about thirty-eight miles upstream as the crow flies General Guderian’s XIX Panzer Corps was launching the body blow that Manstein’s revision of Fall Gelb had called for. One of the mysteries of the war is how Guderian managed to get over 60,000 men, 22,000 vehicles, and nearly 800 tanks through the Ardennes without being observed by British or French reconnaissance aircraft. His passage through the forest was not without problems—despite intense and meticulous planning there were countless traffic jams on the narrow roads and trails—and he was woefully short of artillery for a force of this size, less than 150 guns; still his advance units reached Sedan by the evening of May 12, to find the town deserted, except for the dead horses that littered its streets.

What followed was an extraordinary feat of war, and the confirmation in practice of all Guderian’s controversial and revolutionary theories about waging war, which he had written about so concisely in Achtung—Panzer! in 1937. The French before him across the river not only held the high ground, much of it fortified (though not as well as it should have been—they had not used their time well during the long winter), but had superior numbers of men and artillery, as well as more and better tanks, but from battalion commanders all the way up to the commander in chief they still thought of warfare in the terms of the western front from 1914 to 1918—their preoccupation was to form and hold a line, whether it was on the Meuse or farther north on the Dyle.

Guderian had no interest in lines or in making sacrificial frontal attacks against one; his mantra was movement. Each of his panzer divisions was a self-contained army in miniature, intended to break through the enemy’s line and keep going, without concern for its flanks, or even for its supplies. German fuel tankers struggled to keep pace with the tanks, and where necessary Guderian’s tankers raided enemy supply dumps for fuel, or occasionally stopped and refueled at civilian gas stations along the way. His early training as a radio officer not only kept him in constant communication with his tanks but enabled his tank commanders to call down dive-bombers, “airborne artillery,” to destroy any concentration of the enemy that threatened to halt or slow down their advance.

He was not only ahead of his time but ahead of his own superiors, and turned “a blind eye,” like Admiral Nelson, to orders he did not like. His immediate commander, Colonel General Ewald von Kleist, had ordered a single massive bombing of the French positions overlooking Sedan on the west bank of the river. Guderian disapproved—he wanted “carpet bombing,” as it came to be called, in which successive waves of bombers attacked immediately in front of his advancing troops, a much more demanding tactic both on the ground and in the air.

General Ewald von Kleist.

Not for the last time Kleist ordered Guderian to do as he had been told, but Guderian, in collusion with Luftwaffe Lieutenant General Bruno Loerzer, managed to ensure that Kleist’s order did not reach the pilots of Fliergerkorps II in time, and as a result got exactly the air attack he wanted. It was certainly the most efficient use of air power in direct support of ground operations to date—indeed, perhaps until D-day in 1944—consisting of over fifteen hundred warplanes methodically attacking the French defenses one by one with such thoroughness that by three in the afternoon, partly concealed by immense clouds of smoke drifting from the explosions on the west bank, Guderian’s infantry began to cross the Meuse in rubber boats.

By late afternoon his engineers had completed a bridge that could bear the weight of his tanks, and by nightfall the French line had already begun to disintegrate into shattered fragments. Their dependence on telephone lines rather than radio cost the French dear as bombs cut the lines everywhere, leaving units unable to receive orders or find out how neighboring infantry or artillery units were faring. As a result the appearance of only a few German troops—and very shortly German tanks—behind fragmented French defenders led to panic as artillerymen abandoned their guns and whole regiments of infantry retreated in a confused pêle-mêle “of unimaginable chaos,” which quickly infected rear echelon units, preventing an effective counterattack. For an army that is taught to believe in the importance of forming and holding a line before all other things, the breaking of that line is a catastrophe. The number of troops and tanks Guderian had actually managed to get across the Meuse by midnight on May 13 was comparatively small, as was the size of his bridgehead, but its effect on the French Second Army was to sap the soldiers’ confidence in their commanders and in themselves, which once lost, like time, can never be regained.

In the confusion and mayhem of defeat it escaped everybody’s attention in the French chain of command that Rommel’s breakout to the north of Sedan was not, as everybody expected toward the southwest, in the direction of Paris, but directly west, toward the English Channel. It was not Paris that was suddenly in danger—always the French nightmare—but the Anglo-French alliance itself.

_________________________

* These were basically motorized infantry divisions, beefed up with armored cars and a few light tanks, which had not proved a satisfactory mix during the Polish campaign.

† General Corap, commander of the French Ninth Army, has been criticized for not having destroyed the weir and the lock, but as Sir Alistair Horne points out sensibly in To Lose a Battle (and which is confirmed by looking at the river at this point), doing so might have lowered the level of the Meuse upstream sufficiently to provide the Germans with several places at which it could be forded. All war is a question of hard choices, and each choice has unforeseen consequences.