Belgian refugees and retreating soldiers block the roads, May 1940.

“We Are Beaten; We Have Lost the Battle”

Belgian refugees and retreating soldiers block the roads, May 1940.

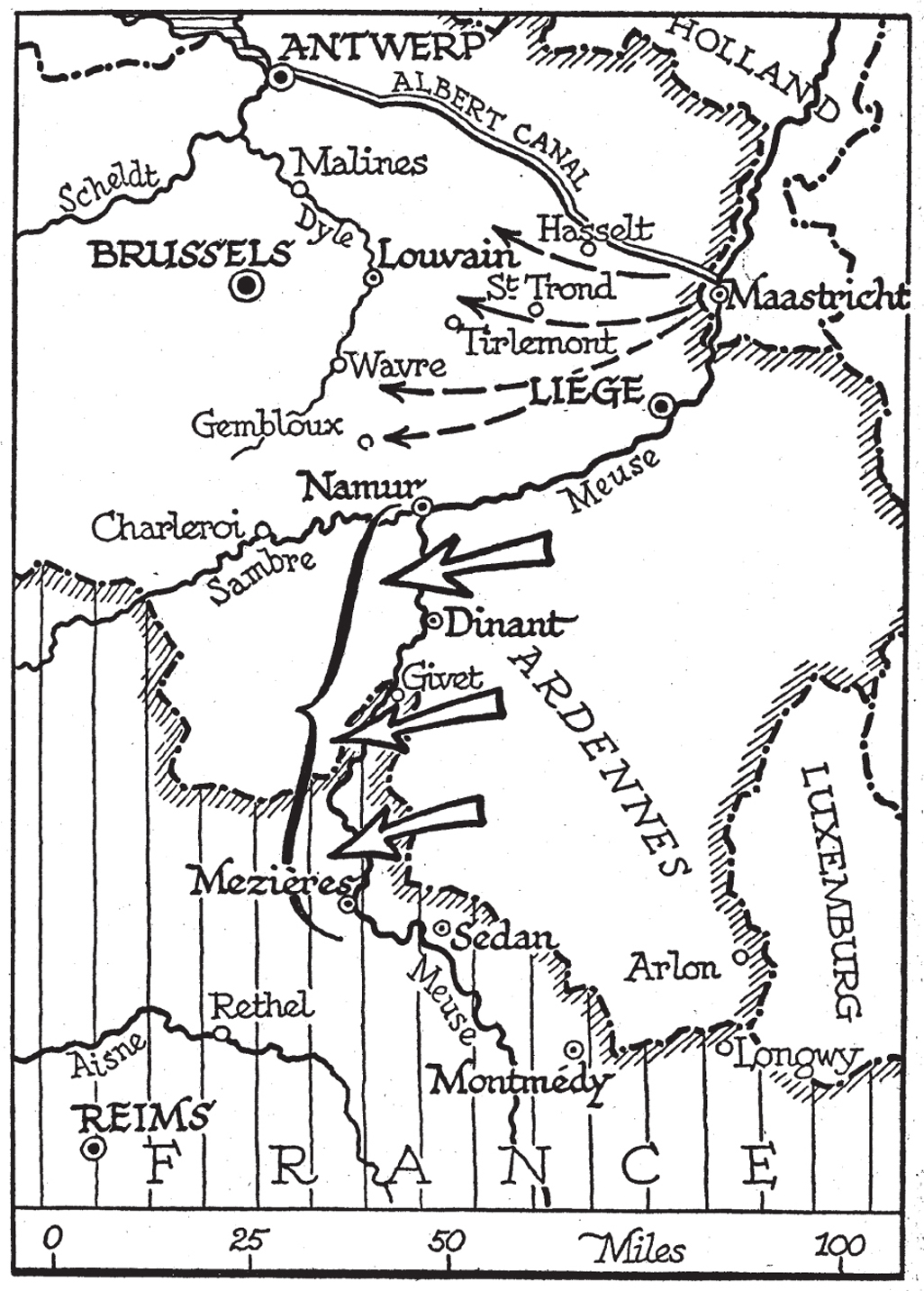

THE DEBACLE AT Sedan grew worse on May 14, despite sacrificial French and British air attacks that failed to destroy the German engineers’ hastily built bridges over the Meuse. Guderian’s bridgehead expanded rapidly, while Rommel forged ahead relentlessly, his lead tanks almost fifteen miles to the west of the Meuse by the end of the day.

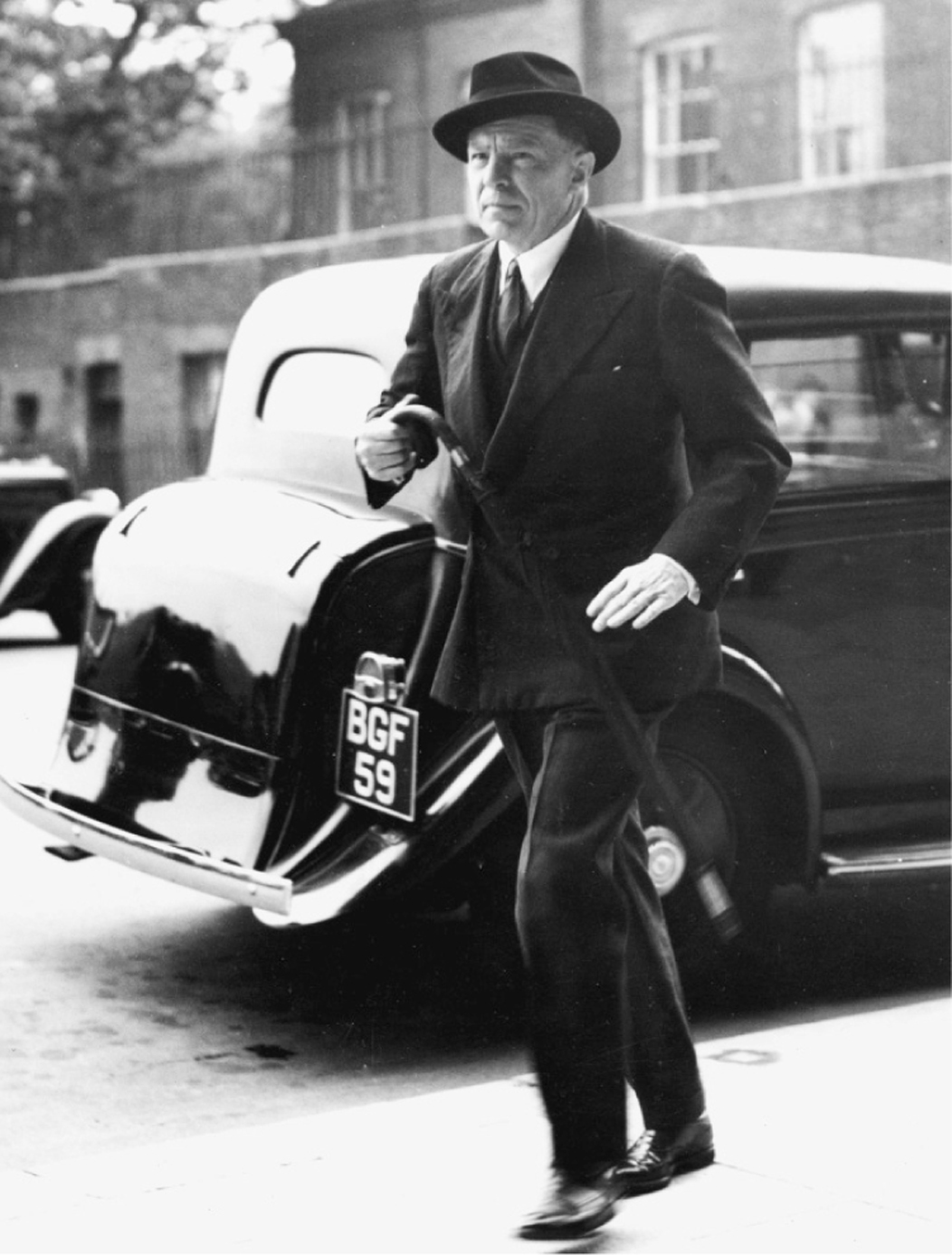

Fighting was severe at first—Rommel, in the lead as usual, was lightly wounded when the tank he was in was hit, and had to abandon it in the middle of a fierce artillery barrage. In Belgium, where the French Seventh and First Armies, the BEF, and the Belgian Army were clashing with the Germans before the Dyle River line and in front of Brussels, General Pownall heard the news of what was happening farther south with restrained alarm: “Bad news from down south. The Germans, inexplicably, have got across the Meuse in the neighborhood of Sedan and Mézières, a big hole twelve miles wide and ten deep, or more. . . . Gort was away for eight hours today—too long at difficult times, but he did well in heartening Corps Commanders and, especially the King of the Belgians who like the rest of his army is in a complete state of wind up.”* Gort’s preference for being up front with his troops tended to make him unreachable, given the chaotic communications between himself and his headquarters.

General Lord Gort.

That night General Corap made the fatal mistake of withdrawing his French Ninth Army from the Meuse and trying to form a line farther west. The withdrawal quickly turned into “a helplessly confused retreat,” which soon became a rout as the five German armored divisions broke through scattered resistance into open country. Around half-past seven in the morning of May 15, Winston Churchill was woken in his flat at the Admiralty with the news that “M. Reynaud was on the telephone at my bedside.” In Churchill’s words, “He spoke in English, and evidently under stress. ‘We have been defeated.’ As I did not immediately respond he said again: ‘We are beaten; we have lost the battle.’ ”

Reynaud may or may not have said that the road to Paris was open, but it was certainly what he thought. It would naturally be the first thought of any Frenchman in the circumstances, and demonstrates that the real goal of Guderian’s armored divisions was not yet clear to General Gamelin at GQG. The French habit of assuming that Paris was at the center of the world made even experienced military leaders like Gamelin and Georges misread the situation. The Germans had made a dash toward Paris in 1870, and they had tried it once again in 1914, so it was difficult to believe they would not do so once more in 1940—after all, they were now only 130 miles away from Paris, with no shortage of excellent roads. Where else would they be going?

The burning question at GQG was no longer whether the Allies could prevent the Germans from taking Brussels, but whether the French government might have to abandon Paris in haste. The next day General Gamelin went so far as to tell Reynaud and Daladier that “he could no longer take responsibility for the safety of the capital after midnight,” a moment of high drama that astonished both politicians, but his pessimism about the safety of the capital—and his helplessness at the speed of the German breakthrough—had already been remarked on the day before. That did not prevent him and General Georges from trying to reassure the British prime minister. General Gamelin informed Churchill that “he viewed the situation with calm,” a wonderfully soothing French phrase, and General Georges, to whom Churchill placed a call, was reported to be “cool,” by which Churchill meant that Georges expressed himself as neither excited nor concerned by events at Sedan.

Clare Boothe, author of The Women and wife of Henry Luce, co-founder of Time magazine, was touring Europe that spring to report on the war; an intermittently astute observer of the social and political scene, she remarked correctly that “the English didn’t really like or trust the French any more than the French liked or trusted the English,” so it is perhaps not surprising that both French generals tried to mislead the British about the seriousness of the situation—after all, nothing could be more humiliating for a French general than to have to tell an Englishman that he had been beaten by the Germans and that German tanks were expected to be in Paris shortly.

Clare Boothe Luce.

Paris being Paris, the rumor that the Germans were on the way spread quickly, and became more dire with each telling. Reynaud no doubt told his mistress the Comtesse de Portes, Daladier told his mistress the Marquise de Crussol, they in turn told their friends, their friends called others. Even on May 15 people in the know, that is in or close to the government, were already advising friends to prepare to leave Paris, and people who were Jewish to leave at once. To all appearances Paris in mid-May was as beautiful and gay as ever, in perfect spring weather. Clare Boothe, usually clear-eyed, rhapsodized over “the gardens of the Luxembourg and the Bois,” over “the gilded corridors of the Ritz,” the crowded, noisy streets, the clink of ice at the polished marble café tables on the Champs-Elysées, the elegant women and well-dressed men—“Paris sera toujours Paris,” as the great French entertainer Maurice Chevalier sang—but “the drawing rooms of Paris . . . became a hotbed of rumors that flew from lip to lip so fast that a few hours later tout Paris knew them.” Behind the façade of elegance and nonchalance there was a growing sense of terror and fear of defeat. Already waves of refugees were thronging the railway stations and filling the roads, not only Belgians now, but French fleeing the fighting before it engulfed them, an eventuality that nobody in Paris had anticipated or prepared for.

None of this was reflected in the British newspapers, or on the BBC news. General Gamelin despised and feared the press, whether French or foreign, so bulletins from the GQG were kept brief and positive. The war correspondents attached to the BEF were also kept on a tight leash. The easygoing familiarity with which General Lord Gort had treated Kim Philby of the Times during the phoney war had been replaced by the stiff upper lip, strict censorship, and encouraging “human interest” stories.

My father, who read all the newspapers intently every day and disliked being interrupted while he was doing so, dropped them on the floor after reading them with a deep sigh and said to nobody in particular, “Lies.” Nanny Low, who picked them up to take the more “popular” ones like the Daily Express and the Daily Mail up to the nursery, read them with greater faith. Those headlines that caught her attention she read aloud to me. Of course in every war “truth is the first casualty,” a remark that goes all the way back to Aeschylus in the fifth century BC and possibly further, and reading the British popular press (and even the Times) seventy-five years later confirms his wisdom.

Some pieces of bad news were impossible to stifle. Holland surrendered on May 15, causing General Pownall to note caustically, “There was no chance that [Holland] would hold out for long, but five days is a little short,” and sending Belgian morale, which was already sinking, into a tailspin. To be fair to the Dutch, their resistance was finally broken by the brutal bombing of Rotterdam, in which 900 civilians were killed, nearly 90,000 made homeless and the center of the city totally destroyed by a firestorm that ignited medieval buildings, an act that caused almost as much worldwide condemnation as the bombing of Guernica in 1937. Still, the tone of the papers in Britain remained strikingly upbeat during the first week of the battle. “ALLIES ADVANCING ON FRONT OF 200 MILES,” ran a banner headline in the Daily Mail on May 10 and “B.E.F. SWINGS INTO ACTION,” three days later. On the same day the newspaper reported that the Belgian Army in the Ardennes was—in that beloved military cliché for headlong flight—pursuing “a strategic retreat to new and more strongly fortified positions,” and that the situation in Holland was “improving,” this just forty-eight hours before the Dutch surrendered.

As would often be the case throughout the war, Royal Air Force figures of German aircraft shot down were delusory, and reports of heavy British and French air raids on German cities at this stage of the war hugely exaggerated. Even the normally sedate Times reported on May 15 that German troops were “falling back” in confusion under “a seemingly endless torrent of [French] bombs,” a complete reversal of actual events, while in Paris the equally respected and respectable Le Temps reported that French tanks and fighter aircraft had proved themselves technically superior to those of the enemy.

Unfortunately most of this was not true. A courageous attempt on the part of the obsolete French bombing force to destroy the bridges built by German combat engineers over the Meuse led to the loss of nearly three-quarters of the French bombers engaged, with no damage to the bridges. An attack by 109 British Blenheim and Battle bombers of the Advanced Air Striking Force led to the loss of forty-five aircraft (and the award of two posthumous Victoria crosses), without inflicting damage to any of the bridges. The RAF effort on May 14 made it clear that daylight bombing in the face of heavy German antiaircraft fire was sacrificial, and helped to further undermine the morale of French troops, since most of the bombs that were dropped by the RAF fell short on them, rather than on the enemy.

May 15 was the last day on which we at home could bask in the belief that things were going well, or at least were under control, and that France’s reputation as the world’s preeminent military power was secure. Possibly my uncle Alex already knew better—friends of his had better sources of information than the newspapers, after all. One of his closest friends was Sir Robert Vansittart, the fiercely anti-appeasement permanent undersecretary at the Foreign Office in the 1930s and head of the “German desk,” now sidelined as the government’s chief diplomatic adviser. Vansittart had been a powerful and well-informed dissenting voice from deep within “the Establishment” against Germany and Hitler’s plans during the governments of Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain, and a loyal Churchillian. Indeed Vansittart was plus royaliste que le roi; his dislike of Germany seemed to many people more deeply ingrained than Churchill’s, and helps to explain why his warnings were ignored by those above him. He was also a man of many talents—he had not only helped Alex to finance London Films through his contacts in “the City,” but as a gifted amateur playwright and songwriter had written lyrics for The Thief of Baghdad in between sifting through every intelligence source from Berlin.

Sir Robert Vansittart.

The end of the phoney war did nothing to slow down Alex’s trips back and forth to Los Angeles, with stops in New York, Lisbon, and Tangiers, and it was already clear both to him and to my father that there was no hope of completing The Thief of Baghdad in the United Kingdom. For once it was not money that was lacking—Alex could always whistle that up out of thin air—but the skilled workmen needed for such a complicated and ambitious project. Every day my father went to the studio to find more of his men “called up,” or shifted to jobs in the armaments business. No matter how late he stayed at the studio, the film languished, having already absorbed some £400,000 ($2,000,000 at the time, at least $24,000,000 in today’s values).† As Alex was so fond of saying, with a disarming shrug, “A lot of money—other people’s money, of course, but still a lot.”

At some point my father may have gone to Paris briefly—my mother certainly said so in her old age—and it is possible. Although he had never mentioned the fact to her, he had a family in Paris, his former mistress and two children, from the days before Alex had called him from his life as a painter to a film career, and it may be that he wanted to make sure they were securely provided for before the Germans reached Paris. My father was not especially secretive; he simply tended to draw a curtain down between one episode of his life and the next, as did his brothers. All three brothers were masters at putting the past behind them, especially when it came to their English spouses, who could scarcely be expected to understand the many convolutions and changes of fortune that had brought them so unexpectedly to England in 1932.

Another possible explanation for the sudden trip to Paris may be that Alex had chosen my father to carry out some last-minute transfers of money. Alex was, after all, the supreme realist—the war would eventually end, like all wars. Unless the Germans won, people would resume going to the movies, the London Films offices in Paris, Berlin, and Vienna would reopen, the European studios now producing Nazi propaganda films would return to producing more normal fare, the copyrights to Alex’s old films would be as valuable as ever, perhaps more so, and in the meantime the more money that could be placed safely out of harm’s way in Swiss and American banks, the better. Nobody could have been better shaped to play this last-minute role than my father, an artist with shabby clothes, a battered hat, and a cigarette adhering to his lower lip in the French manner, whose friends included almost every painter, sculptor, and filmmaker of note in France, multilingual (all the languages he knew spoken with a Hungarian accent of course), and gifted most improbably with a genuine British passport and impeccable visas, thanks no doubt to Sir Robert Vansittart. It would have been hard to find a figure less likely to arouse the suspicion of the authorities in France than my father, or with better credentials and more friends.

Vincent would no doubt have been happy to escape from the problems of The Thief of Baghdad for a few days. It was in any case a truly international film. Its first director (there would be several) was Ludwig Berger, a German Jew and a friend of Alex’s from his filmmaking days at the UFA studios in Berlin in the 1920s, one of the screenwriters was Alex’s old friend from his student days in Budapest Lajos Bíró, and the music score was being composed by my father’s old friend Miklós Rózsa, who had also composed the score for The Four Feathers. The cinematographer was another old friend from my father’s days as a painter in Paris Georges Perinal, and the two major male stars were an anti-Nazi German refugee, Conrad Veit, and an Indian, Sabu, the young mahout whom my Uncle Zoli had “discovered” in India while making Elephant Boy. Only my uncle Alex could have collected all these people together in the expectation that they would produce a successful English-language motion picture, and it may well have been that it was not only my father who had matters to wind up in Paris before the Germans arrived there, but many of the people connected with the film. In any case, he was home before May 15, his suitcase stuffed with tins of foie gras from Fauchon, the great purveyor of gourmet foods in the Place de la Madeleine, which he would not revisit until 1945, and for my mother a beautiful gold brooch from Cartier on the rue de la Paix in the shape of a rose mounted with diamonds, each petal articulated by tiny gold springs so that it could be changed from bud to an open flower. My father was as interested in jewelry design as in any other form of art, and had old friends in the Cartier design studio. This was not so much a piece of jewelry as a unique work of art. Ever the forgetful artist, Vincent was apt to overlook birthdays and anniversaries, but instead had moments of what sometimes seemed like spontaneous and outrageous generosity. In this case, it was something in the nature of a preemptive strike, since he was about to make my mother do the last thing she wanted to do. The Cartier rose was at once a gift offering and an apology in advance.

* * *

The bulk of the BEF had moved forward to the Dyle River in Belgium, the beauty of which one English officer compared to the Thames Valley, so efficiently that its GHQ was left behind, struggling to keep up. By May 16, after a few clashes in which the Germans learned, as their fathers had in 1914 at Ypres and Mons, just how effective the massed rifle fire of well-trained British regulars was, it was becoming obvious that a line on the Dyle, the heart and soul of General Gamelin’s Plan D, would be difficult to hold. The Belgian Army to the north of the BEF was at best shaky, the First French Army to the south had advanced much more slowly than the British and was beginning to give up ground under pressure, and a withdrawal to the next defensible line, the Senne Canal, seemed the obvious move.

The rivers and canals in central Belgium all run more or less parallel, and the next few days would see the Allied armies moving back from one river or canal to another. If the BEF’s neighbors to its north and south gave way, the British risked being left in a salient with wide-open flanks, but each withdrawal would expose more of Belgium to the enemy. Retreat to the Senne would almost certainly mean the loss of Louvain; a retreat to the Escault River (or the Scheldt, as it is known in Belgium), which many people in the French and British armies thought would have been a better place at which to form a line than the Dyle in the first place (the Dyle is hardly more than a shallow stream, the Escaut is a major river), would mean abandoning Brussels, and thus undermine any reason for the Belgian Army to continue fighting. Any retreat farther west to the Lys River would bring the Allied armies back to the French frontier where they had started from, and also risk the loss of Antwerp, the major port of northern Europe and a permanent British strategic interest on the Continent.

That General Georges had delegated the “coordination” of the three armies to General Billotte was already becoming a difficult problem. “Coordination” is not the same thing as supreme command. Billotte’s tears at the prospect were justified—his was not a dominating personality, the British and the Belgians received no orders from him; indeed he seemed barely able to animate the French First Army, which he commanded. It was his decision to withdraw to the Senne, a huge “bound” to the rear for the BEF, with four divisions to disengage, and nearly ten thousand vehicles to move. The news so surprised the BEF that General Pownall sent a liaison officer to emphasize they needed a clearer sense of “policy and timing,” but none was forthcoming.

The fact that the main German attack was taking place seventy miles farther south, let alone that Premier Reynaud and General Gamelin already thought that the war had been lost, had not yet penetrated to the Allied armies fighting on the plains of Belgium any more than it had to the French or British public.

_________________________

* The nearest American equivalent to getting one’s “wind up” is “scared shitless.” It derives from the fact that horses often get frightened when a strong wind is blowing from directly behind them.

† This is about the same as the cost of The Wizard of Oz, and a little more than half the cost of Gone with the Wind.