A German Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombing.

“The Mortal Gravity of the Hour”

A German Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombing.

AMORE IMPORTANT VISITOR than my father arrived in Paris late in the afternoon of May 16, having flown from London to see for himself what the situation was. Winston Churchill had spent the past two days with his chiefs of staff and the War Cabinet considering Premier Reynaud’s alarming early-morning telephone call on May 14, and repeated messages since then warning of disaster and appealing for more British fighter squadrons. Even more alarming was a guarded telephone call from General Lord Gort to General Sir John Dill, until recently one of Gort’s corps commanders and now vice-chief of the Imperial General Staff, to say that the French were thinking of withdrawing from Belgium altogether owing to the “deep penetration” of German armored forces toward Paris “from the direction of Mézières.” This is a reference to Rommel’s 7th Panzer division, which was already in Avesnes, which he took on May 16, and after which Rommel wrote, “The way to the west is now open.” His tanks would shortly be advancing up to fifty miles a day.

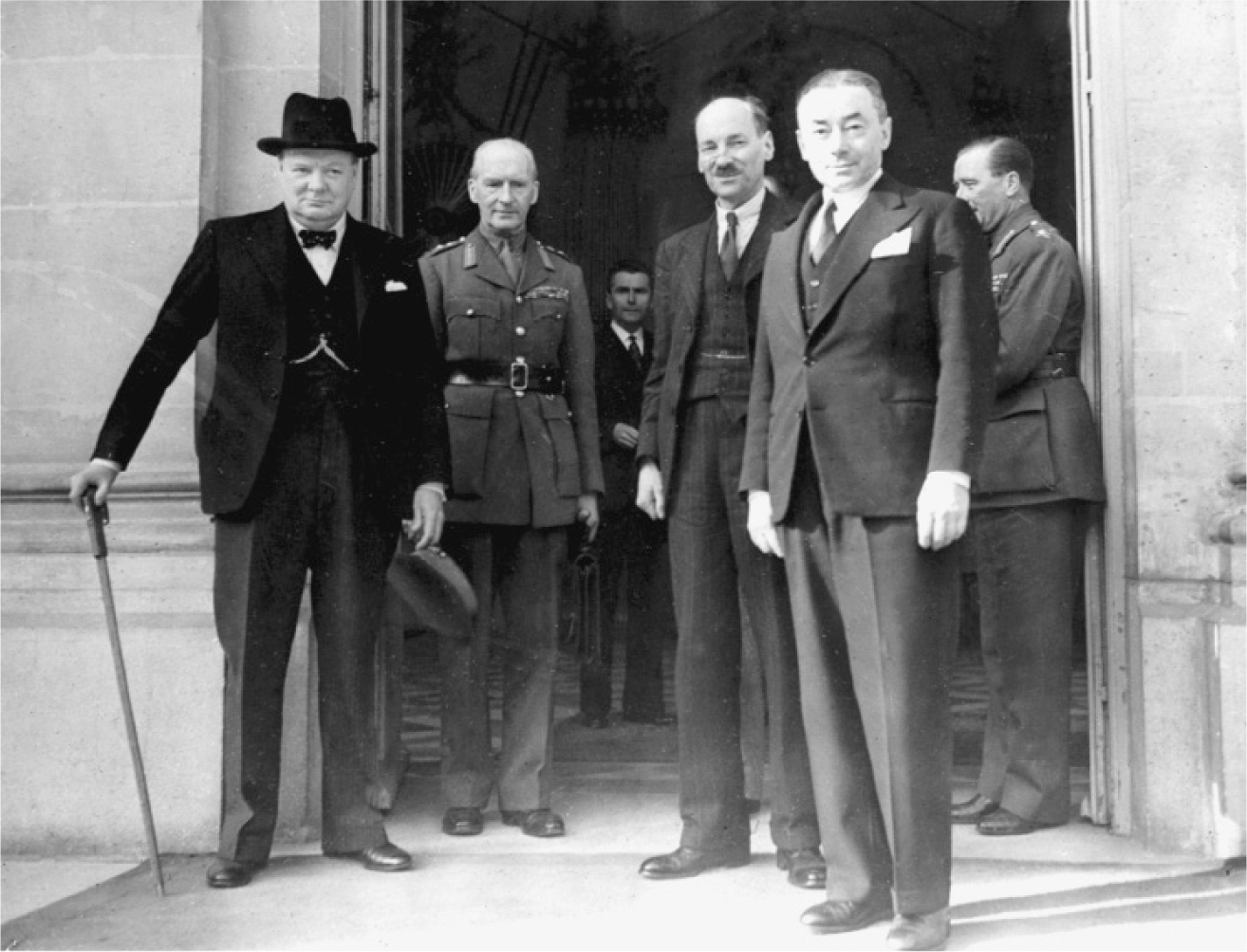

Churchill, General Sir John Dill, Attlee, and Reynaud at a meeting of the Supreme War Council, Paris.

Among the prime minister’s attributes was a well-developed nose for disaster, as well as a gamecock’s fighting instincts. Nobody had greater, or more varied, experience of military and naval disasters over many decades from the reign of Queen Victoria to that of her great-grandson George VI than the prime minister. Few people had stronger nerves, or a more deeply ingrained belief that attack is the best form of defense too, but Churchill came to the Supreme War Council determined to listen. His respect for the French Army remained unshaken, and although the War Cabinet was cautious about any undertaking to send more RAF fighter squadrons to France, the prime minister, always a Francophile, was inclined to be sympathetic toward Reynaud’s appeal on the subject, and had sent four more fighter squadrons to France in the morning.

Unfortunately neither Premier Reynaud nor General Gamelin understood that the British fighters were a part of an intricate and complex defense system—admittedly the most visible and glamorous part, but not intrinsically more important than the radar towers along the southern coast of England, or the young women of the WAAF* who plotted incoming attacks at Fighter Command Headquarters and watched the radar screens, or the repair facilities scattered throughout southern England that could take a damaged Hurricane or Spitfire and restore it to fighting trim, sometimes overnight (and often returned to the fighter squadrons by young civilian women ferry pilots), all of it linked together by hundreds of telephone and telex lines buried deep underground and armored in concrete to withstand even a direct hit by a bomb.

The king and Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, commander in chief of Fighter Command.

Churchill himself did not yet appreciate or understand the complexity of Fighter Command, or the degree to which the precious fighters and their pilots would be wasted operating from makeshift airfields in France without the organization that Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, commander in chief of Fighter Command, had been building up painstakingly since 1936. Sending more Hurricanes to France—there was no thought of sending the more sophisticated Spitfire, which was more difficult to manufacture and whose narrow undercarriage track made it unsuitable for rough fields—was, in Dowding’s mind, “turning on a tap” that no politician would have the courage to turn off, and that risked leaving England defenseless when the Luftwaffe attacked.

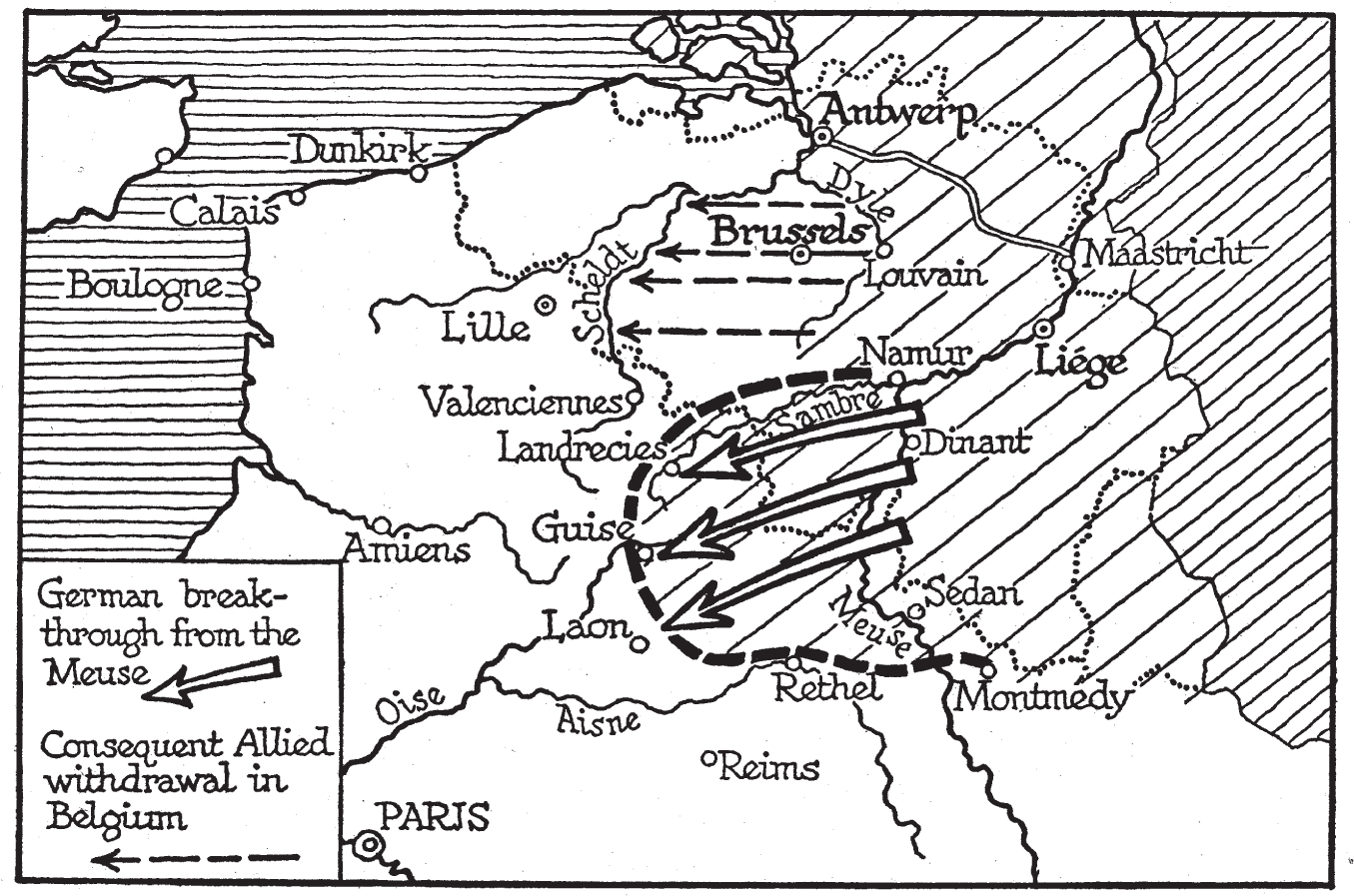

The meeting took place in Reynaud’s “study” on the Quai d’Orsay, and Major-General Hastings Ismay, Churchill’s military adviser, thought as he looked at the faces of Reynaud, Daladier, and Gamelin, “The French High Command are beaten already.” The meeting was not made more cheerful by the sight through the windows of clouds of smoke and pieces of charred paper rising from bonfires in the gardens as “venerable officials [pushed] wheelbarrows of archives onto them,” a sign that the French government was already planning to leave Paris. “Utter dejection was written on every face,” Churchill wrote, remarkably for someone who did not normally pay much attention to other people’s feelings. Everybody was standing—there was no big conference table. General Gamelin stood beside what Churchill described as “a student’s easel” with a map that showed “a small but sinister bulge at Sedan.” In a flat and unemotional voice Gamelin explained the military situation. The Germans had broken through and were advancing “with unheard-of speed towards Amiens and Arras, with the intention, apparently, of reaching the coast at Abbeville or thereabouts. Alternatively they might make for Paris.” It still does not seem to have dawned on Gamelin that Abbeville loomed larger in the Germans’ minds than Paris.

Gamelin talked for several minutes, after which there was, understandably, a long and uncomfortable silence. At last, the prime minister asked where the strategic reserve was? “Breaking into French, which I use indifferently (in every sense),” he recalled, he asked, “Où est la masse de manoeuvre?” General Gamelin shrugged and said, “Aucune.” (There is none.)

Churchill was “dumbfounded,” he later confessed, although whether he was quite as surprised as he claimed in his memoirs to have been is open to doubt. After all, he had flown from London with Generals Ismay and Dill. Ismay had never had any faith in Gamelin’s Plan D or the idea of fighting the Germans in central Belgium, and Dill had served in France under Lord Gort and had had every opportunity to observe the flaws in the French Army at close range. As for Gamelin’s somber tour d’horizon, he passed over the fact that he had a powerful mobile strategic reserve, but had placed it in northern France to advance into Holland and support the Dutch when the battle began. With the collapse of resistance in Holland what remained of General Giraud’s Seventh Army should have been moved south immediately to reinforce the flagging Ninth Army before Sedan. It was not that there was no mobile strategic reserve—Giraud had not only some of the French Army’s best infantry divisions but three armored corps with heavier and better armed tanks than the Germans—it was simply in the wrong place.

Churchill hit on this immediately, but Gamelin explained smoothly that he had not been able to effectuate this movement because the Belgian railway workers were on strike. “Shoot the strikers,” Churchill replied,† sharply changing the tone of the meeting. It is possible, even probable that Churchill merely wished to light a fuse under Gamelin, rather than to suggest that the French Army start executing Belgian railwaymen. Certainly he was annoyed that the French commander in chief had spent five minutes talking about his woes without proposing any solution to them. What Churchill saw when he looked at the map was a long, narrow German salient created by armored divisions that were moving much faster than the infantry divisions marching far behind them on foot—a perfect opportunity for a counterattack on the exposed German flanks, which was exactly what Hitler and his senior generals feared would happen.

But Gamelin would have none of it. The French troops, he insisted, had been prevented from counterattacking by German bombing—he needed fighter aircraft to protect the infantry, and also the railway lines over which reinforcements would have to be brought up. This was at last something on which all the French present could agree—lack of British fighter aircraft was responsible for the German breakthrough, and it could only be halted by more British fighter squadrons, which were required immediately. As M. Daladier put it, perhaps giving away more of the truth than Gamelin would have wanted to, “If the French infantry could feel that the fighters were above protecting them, they would be given confidence and would not be taking cover when the tanks came along.”

This was the first admission that the real problem was the morale of French soldiers, who were unable to hold their ground when attacked by Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers, even though dive-bombing produced far fewer casualties than a well-organized artillery barrage, or when they saw German tanks approaching in the distance. The fact was that the French were fleeing from even the rumor that German tanks were near, and that their nerve was broken by the howl of the Stukas as they dived—the Germans had cleverly attached a siren under each wing of the Stuka, “Jericho Trumpets” as they were called, which gave off a howling, piercing, banshee screech that froze men’s blood. It was a classic case of the bark being worse than the bite.

If Gamelin was reading the messages on his desk, he must have known how badly things were going. A staff officer he sent to see for himself what was happening on General Corap’s front facing Sedan reported back, “This Army is in an indescribable disorder, troops are falling back on all sides, Army H. Q. have lost their heads, they do not even know where their divisions are. The situation is worse than anything we could have imagined.” This was a rout that could hardly be stopped by more fighter aircraft, and Gamelin knew it, despite his carefully maintained façade of eerie, calm self-satisfaction.

Churchill could see well enough that the demand for more fighters was merely a convenient way of ignoring the fact that the French divisions at Sedan had performed very poorly, and at the same of shifting the blame for the French Army’s failure to stop the Germans from their own shoulders to those of the British, and did his best to explain in rational military terms why this was not the case. Tanks, he pointed out, could not be stopped by fighter aircraft armed with .303-caliber machine guns, the bullets of which would simply bounce off their armor. “It was not reasonable that the British aircraft should be required to take on German armoured fighting vehicles. This should be done by ground action,” he pointed out.

The French had ample numbers of seventy-five-millimeter cannon, the famous “French seventy-fives,” and fired over open sights these could destroy any tank the Germans had with one shot. As for bridges, they were notoriously difficult targets for bombers,‡ and the Germans had plenty of antiaircraft guns with which to defend them—losses would be crippling. These reasonable arguments accomplished nothing. Whatever their other differences, and there were many, Gamelin (who feared for his job), Daladier (whose protégé Gamelin was), and Reynaud (who wanted to get rid of them both) all agreed that only the prompt arrival of British fighter squadrons could prevent the German armies from continuing their advance toward Paris. If the Germans reached Paris, Daladier said, the war would be lost.

Churchill could already see where all this was leading, and although he kept it to himself for the moment it was clear enough to him that the war would not be lost if the Germans reached Paris—the French Army was still big enough to hold a line somewhere in France and fight it out, and if it could not, then Great Britain would have to carry on the war alone if necessary, in which case the fighter squadrons would be essential for its survival.

As the meeting dragged on disputatiously—Gamelin remained silent, as if he had no place among all these civilians and foreigners and was anxious to be back at Vincennes, where nobody could ask him inconvenient questions—Churchill finally offered to add six more squadrons to the four that had been promised that morning, subject to the approval of the War Cabinet. Although there was no particular magic in the total of ten fighter squadrons except that it was a round number, it seemed to satisfy the French. By Churchill’s reckoning this would represent one-quarter of the number of squadrons that would be needed to defend Britain, a figure he seems to have made up by himself—in fact Air Chief Marshal Dowding had stated that he needed fifty squadrons of fighters only the day before in a charged confrontation at the War Cabinet—but it was no doubt intended to impress the French, or at least to shut them up for the moment, and in that it succeeded.

Churchill went back to the ornate calm of the British Embassy on the rue du Faubourg St. Honoré and composed a careful message to the War Cabinet asking it to agree to send six more fighter squadrons at once. His message makes it clear that his recommendation to send them is not basically a military decision but a political one. “It would not be good historically if their requests were denied and their ruin resulted,” he wrote, prompting one of his secretaries to say, “He is still thinking of his books,” although it may be that the prime minister was already thinking of the judgment of history, and that it would not look good if Britain failed its only ally at this crucial point in the war. He emphasized, in another powerful phrase, “the mortal gravity of the hour,” and the importance of giving the French Army “the last chance . . . to rally its bravery and strength,” and ended by asking for the reply to be telephoned to General Ismay “at Embassy in Hindustani,” Ismay having previously worked out that two British officers communicating in Hindustani would be safe from any Frenchman (or German) who was listening in on the line.

At 11:30 that night Ismay received a call from London. The answer was “haan,” or yes.§ He informed the prime minister immediately, who was so pleased that he decided to break the good news to M. Reynaud personally, and bundled General Ismay into an embassy car to drive to the premier’s apartment at once.

Reynaud had already retired for the night, much to Churchill’s surprise since he was himself an indefatigable night owl, so the two Englishmen were obliged to wait in the darkened living room while the premier was woken. Not being a ladies’ man the prime minister failed to notice a fur coat and several items of intimate female clothing strewn about the room, so when Reynaud at last emerged in his dressing gown to hear the good news, Churchill could have no notion that the Comtesse de Portes, Reynaud’s mistress, was listening from behind the door to the bedroom. Many difficulties over the next three weeks might have been solved had Churchill known of the degree to which Reynaud was subject to the wishes and opinions of his mistress, whose outspoken Anglophobia and disapproval of the war was one more factor in the rapid deterioration of the alliance.

_________________________

* Women’s Auxiliary Air Force.

† Churchill later denied saying this, but his words were confirmed by General Ismay.

‡ With the aircraft then available for the task, Battles and Blenheims carrying 250-pound bombs, it was indeed an impossible task. Later in the war it would be calculated that a minimum of 250 tons of bombs were required to guarantee the destruction of a bridge.

§ As Ismay points out, this was not a new or original idea. Prime Minister David Lloyd George did the same thing at crucial moments during the Versailles peace conference, except that in his case he arranged for a Welsh speaker to be present in London.