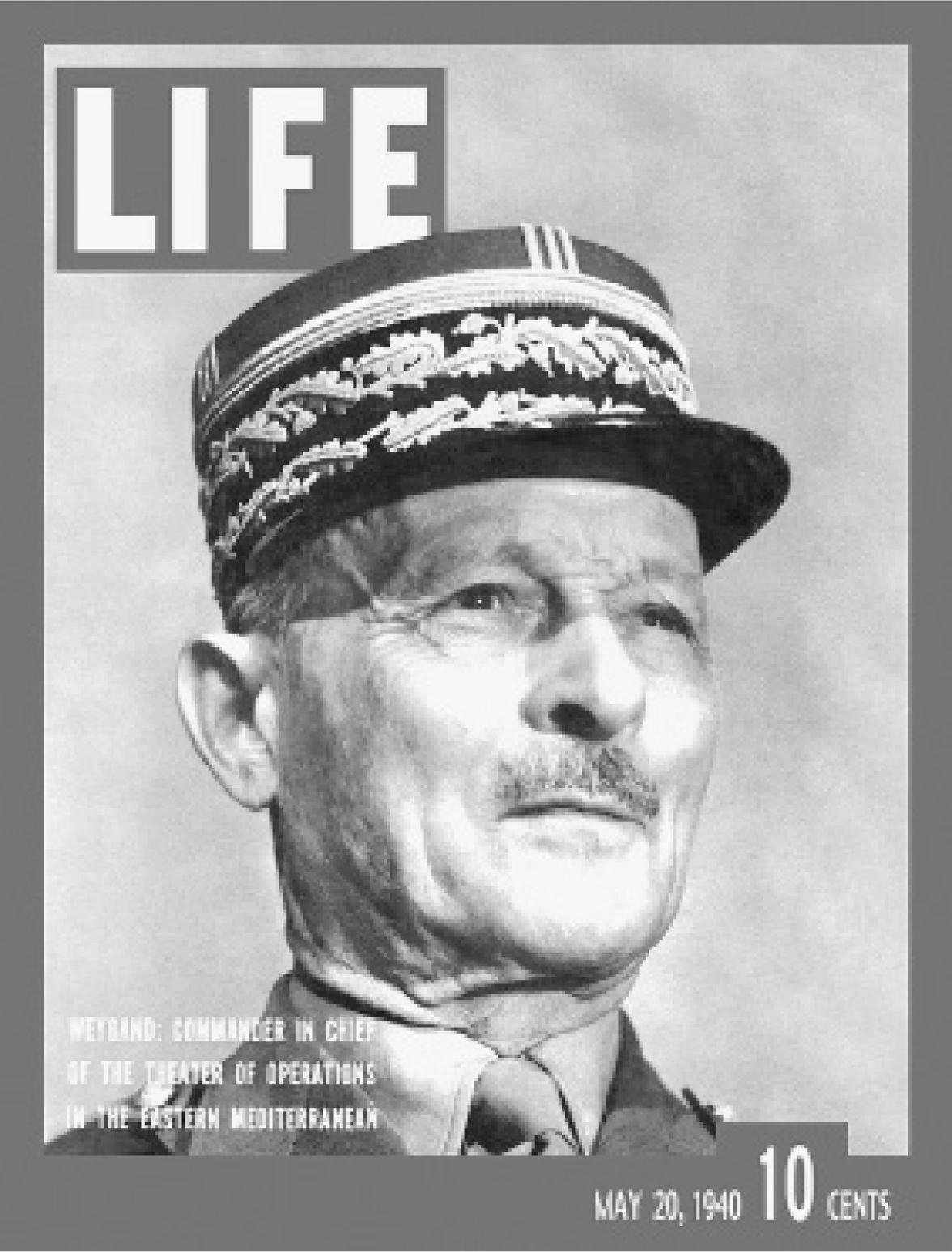

General Weygand.

May 20, 1940:

“A Pretty Fair Pig of a Day”

General Weygand.

SUCH NEWS AS was printed in the United Kingdom did not of course reflect the dramatic visit of the prime minister to Paris, or the real state of the French Army. The Times, usually cautious and accurate but still under the spell of GQG’s communiqués, hailed “the vigorous counter-attack” of the French at Sedan, and the “powerful” bombing attacks of the RAF against the German pontoon bridges over the Meuse. On May 17 the Times described the German attack through the Ardennes as “small in scope compared with the momentous battles farther north,” the exact opposite of the truth, and referring to General Corap’s troops, hailed “the gay spirits of these lean, wiry young men who in an hour or two were to go back into the lines,” when in fact they were retreating in disorder, having abandoned their guns.

In Well Walk, Hampstead, the Times did not appear in the nursery. Nanny Low read the Daily Express and the Daily Mail, which ran stories of the “magnificent” French Army, of the Belgians and Dutch driving back the Germans, and of titanic air victories. These Nanny perused carefully through her thick reading glasses, and carefully clipped out stories like that of the four Battle bomber crews, the only ones of their squadron to have returned from an attack on the bridges over the Meuse, who bravely volunteered to go back and try again. None of them returned, but “the bridge was destroyed.” Several different versions of this story ran in all the “popular” press, and Nanny not only read it aloud to me but tucked it in the corner of one of her framed photographs of other children she had cared for—she had a nephew who was an air gunner in the RAF, so she had a particular interest in stories of RAF heroism, of which there were plenty at the time, perhaps because the RAF was better at what is now called “public relations” than the other two services. Needless to say, the press did not run stories about the fact that the RAF raids on the Meuse bridges had produced the highest rate of loss in RAF history without seriously inconveniencing the Germans.

British eyes were still fixed on the battle in central Belgium, not on the collapse of the French Ninth Army at Sedan, about which even those much better informed than the average newspaper reader remained ignorant. It was the BEF fighting successfully against the odds that held the public’s attention. Not only were they “our boys” but many of the names of places they passed through on the way to the Dyle River were engraved in the memory of the previous generation: Mons, Ypres, Passchendaele, familiar landmarks of the great battles in Flanders that had cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Britons only twenty-six years ago. The names of the regiments involved were recognized all over the United Kingdom, since each regiment had strong local roots: the Cheshire Regiment, the Middlesex Regiment, the Gordon Highlanders, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, the Royal Norfolk Regiment, the South Staffordshire Regiment, the West Yorkshire Regiment, the Sherwood Foresters, the Lancashire Fusiliers, the North Staffordshire Regiment, the Royal Welch Fusiliers, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, the Black Watch, the Buffs, the Green Howards, the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment, the Gloucestershire Regiment, the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, the list goes on and on of battalions from almost every one of the famous regiments of the British Army, each with its own traditions, peculiarities of dress, numerous battle honors won in every corner of the globe, and turreted and mullioned home depot in its county seat, and that is without counting the five regiments of the Foot Guards (the Grenadier Guards, the Coldstream Guards, the Scots Guards, the Irish Guards, and the Welsh Guards) or storied cavalry regiments now converted to tanks or armored cars like the King’s Royal Hussars, the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry, the Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards, the 12th Royal Lancers, the Queen’s Bays, the 10th Royal Hussars, name after name familiar in British history.

There can have been few people in the United Kingdom who did not have a relative who had served or was now serving in one of these regiments, no county or big city throughout the United Kingdom that did not pride itself on its local regiment and its history, from the Tyneside Scottish to the Durham Light Infantry. Of course there were specialist services too, the Royal Artillery, the Royal Engineers, the Royal Army Service Corps, and so on, not to speak of the Royal Air Force, but this was still an army of nearly 400,000 men whose territorial and local roots remained relatively strong, and most of whose units retained fierce regimental loyalty and local pride.

A number of its officers were noblemen, including the 9th Duke of Northumberland, a lieutenant in the 3rd Battalion the Grenadier Guards, the 10th Viscount Downe who commanded the 69th Brigade, and of course the 6th Viscount Gort, the commander in chief. Despite the intermingling of Territorial battalions, the BEF still reflected the older British Army, in which musketry, discipline, and regimental esprit de corps were all-important, and the bayonet charge remained the final arbiter of battle.

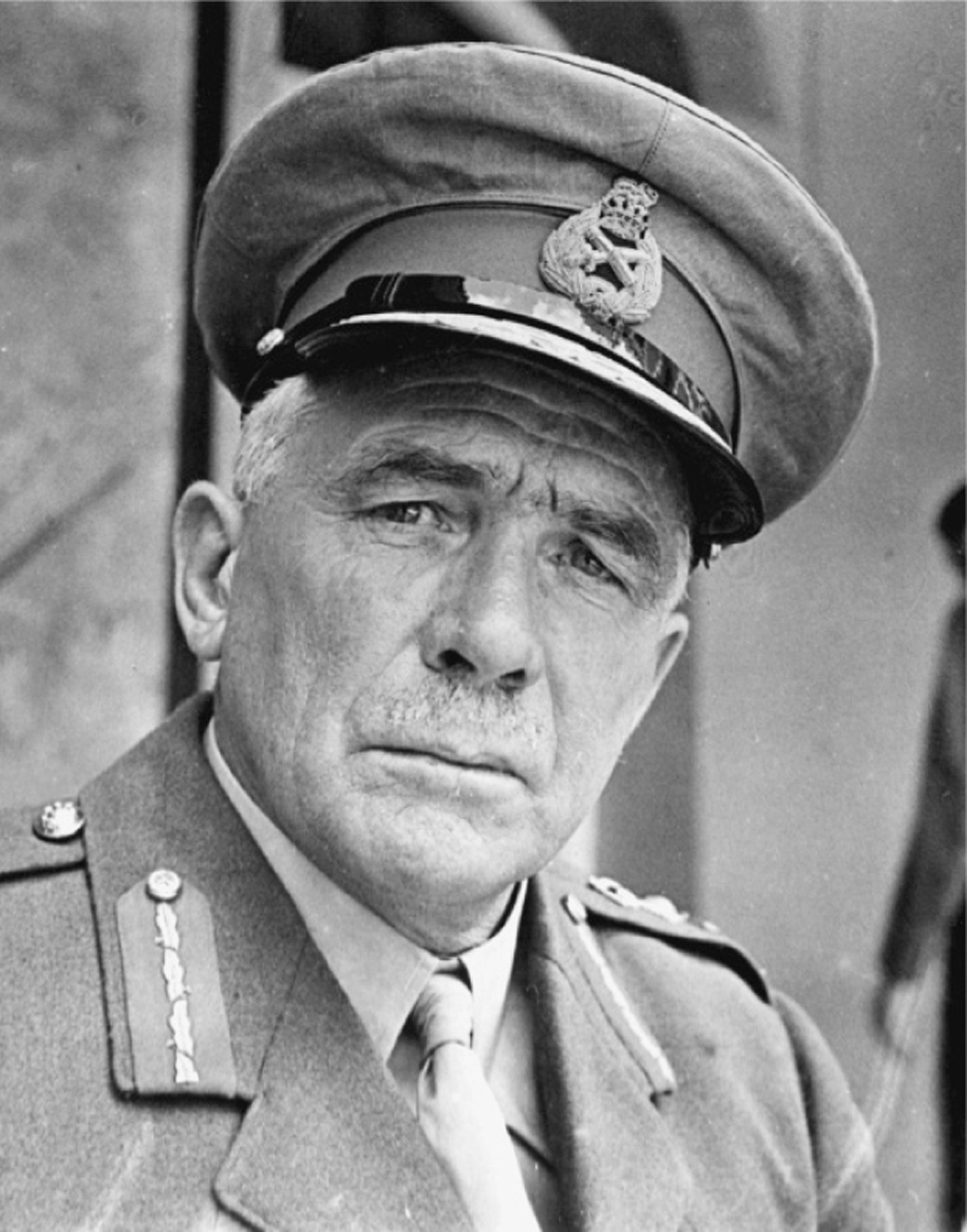

This was the army that had advanced to the Dyle River on the orders of General Gamelin, and had already been ordered to fall back by stages to the Escaut (or Scheldt) River, since the Belgian Army to its north was withdrawing and the French First Army to its south was “shaken,” as General Pownall tactfully described it. Pownall already foresaw that Brussels was a goner, and complained that General Billotte, to whom General Georges had delegated the “coordination” of the three northern armies, was unable or unwilling to do so, with the result that nobody was effectively in command—a very dangerous situation against a well-trained, more numerous, and better-armed foe. An army is never in greater danger than when it is in retreat, and there was a real possibility that the entire Allied line from north of Brussels to the Ardennes might simply disintegrate—already there were reports of Belgian soldiers fleeing in large numbers without their rifles, hopelessly mingled with hordes of desperate civilian refugees who blocked the roads, the beginning of a huge exodus of misery that would soon involve millions of people. In these circumstances it was something of a miracle that the BEF managed to withdraw in relatively good order despite some heavy fighting, first to the Senne River, then to the Dendre, and finally to the Escaut, where the BEF was firmly established by midnight of May 19.

The BEF had advanced to the Dyle River in three days and it took it three days to march back again, reminding more than one participant of the old nursery rhyme commemorating the futile maneuvering of HRH Prince Frederick, the Duke of York, second son of King George III, in the Flanders campaign of 1793–1794 against the French:

Oh, the grand old Duke of York,

He had ten thousand men;

He marched them up to the top of the hill,

And he marched them down again.

This was, surely not accidentally, the last time a member of the British royal family had personally commanded troops in the field.* In May 1940, of course, the BEF was obeying the orders, or perhaps more accurately the vaguely expressed misgivings of General Billotte. British casualties were still considered “light,” mostly from German dive-bombing of the roads, and few vehicles were lost except for the heavy “I” tanks—slow, cumbersome, and poorly armed—which the striking Belgian railwaymen refused to load onto flatcars, so the BEF returned to the Escaut more or less intact.

Disappointingly, even the Escaut turned out not to be as formidable a military obstacle as General Billotte had supposed from looking at the map. Nobody seems to have informed him that the water level had dropped several feet because of “a long spell of dry weather” and the closing of the sluices farther upstream, so there were places where it would not be difficult for German infantry to cross. Falling back to the Escaut carried with it other problems—the loss of Brussels and Antwerp, thus making it increasingly difficult for many Belgians to see any good reason for continuing to fight, and eliminating one of the major strategic reasons for the BEF to be in northern France in the first place.

Even more alarming was the fate of what remained of the French Seventh Army, which was in the process of disintegrating as it attempted to move behind the BEF to reinforce the collapsing Ninth Army farther south—its commander, General Giraud, one of the more energetic and competent French generals, who would go on to become briefly a rival of de Gaulle’s, was captured by the Germans in his command car as he tried to rally the rest of his army. Thus what remained of the best-equipped French army was fed into the battle piecemeal, instead of being concentrated for a single powerful counterattack—another major tactical error on the part of General Georges.

Gort’s line on the Escaut was badly stretched, for he had only seven divisions with which to hold a front thirty miles long, and on one of his rare visits to Gort’s headquarters the hapless General Billotte held out little hope that the gap farther south could be filled in, which meant that short of a miracle Guderian’s armored divisions would shortly advance straight across the BEF’s tenuous lines of communication with the major ports of Le Havre, Brest, and Cherbourg, and leave it stranded in Flanders—cut off and desperately short of supplies and ammunition. The spearhead of Guderian’s panzer forces, Billotte confided, was already close to Cambrai, and he had nothing with which to slow down or stop this rapid mechanized march to the sea—the Germans would very shortly be closer to the English Channel than the BEF was.

If what Billotte intended was to put in Gort’s mind the idea of moving the BEF south to join the shattered fragments of the French Ninth and Seventh Armies in forming a line on the Somme, he failed. On the contrary, his “gloomy” visit to Gort at midnight on May 19 seems to have been the point at which it first dawned on the British commander that the only way to save the BEF might be to carry out a fighting retreat to Dunkirk and evacuate it altogether. Gort was the bravest of generals, and the least “political”—that and his nickname in the British Army, “Fat Boy,”† may have led the French high command to underrate his intelligence—but he had not forgotten that his orders gave him the right to make a direct appeal to his own government if he thought that the BEF was in danger, and that preserving the BEF was his responsibility, and not that of the French chain of command.

It was all very well for Premier Reynaud to complain to British Ambassador Sir Ronald Campbell “that British generals always made for harbors in an emergency,” but Gort was of all British generals the one whose first instinct was to stay and fight. He had loyally obeyed the few orders he had received from General Billotte over the last nine days, but Billotte now seemed to have no idea what to do, and assuming his information was correct Gort might soon have German armored divisions behind him as well as on his flanks.

In “guarded language” General Pownall, Gort’s chief of staff, conveyed his commander in chief’s concerns to the director of military operations (DMO) in London, whose reaction Pownall described as “singularly stupid and unhelpful,” and who wanted to know why the BEF couldn’t “make for Boulogne,” revealing that it had not yet occurred to anybody at home that the Germans would almost certainly reach Boulogne before the BEF could get there, and that by moving his army to the northwest Gort would be exposing his right flank to the German armored divisions.

The next day (“A pretty fair pig of a day,” noted Pownall) began with the arrival of the chief of the Imperial General Staff himself, Tiny Ironside, bearing an order that the BEF retire southwest, toward Arras—a reflection of Churchill’s belief that if the BEF could move south and the French First Army could move north, they could meet and squeeze off the German “bulge.” Pownall described this as “a scandalous (i.e. Winstonian) thing to do and in fact quite impossible to carry out,” and he was right.

The BEF was only just beginning to consolidate its position on the Escaut facing west against a vastly superior force, and was now being asked to abandon that position before they were even dug in. Very fortunately, the news that Arras was already under attack by German armor made the order academic. From Arras, it must have occurred to everyone, it is only ninety miles by good roads to Calais and the English Channel.

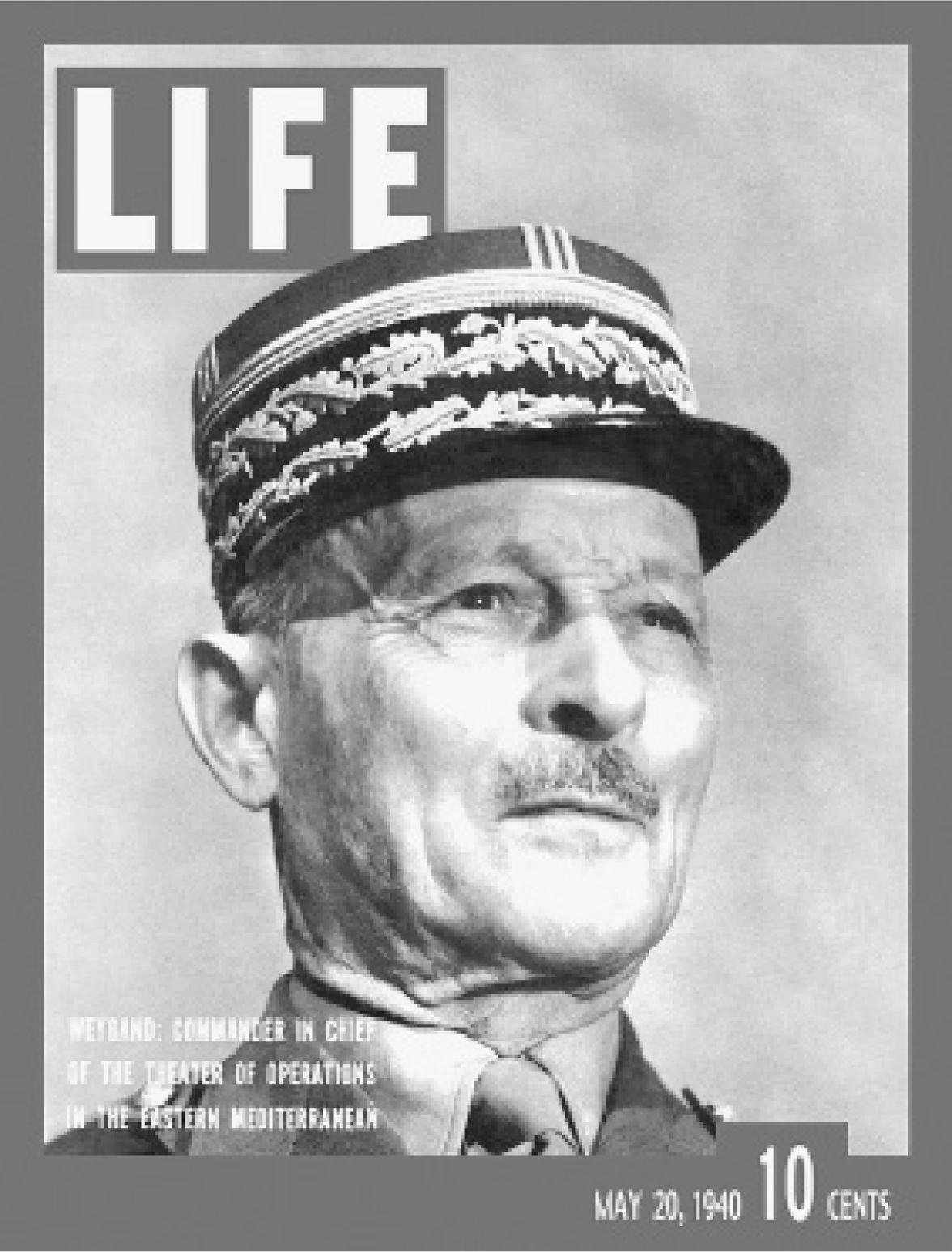

General Ironside.

Ironside was a professional soldier, which is to say a realist. “At this moment it looks like the greatest military disaster in all history,” he confided to his diary before leaving to visit Lord Gort’s headquarters at Wahagnies, close to the Franco-Belgian border. By the time he arrived there a major French political crisis was in full swing. Premier Reynaud had reshuffled his cabinet, taking over Daladier’s place as minister of national defense—Daladier was moved, reluctantly, sideways to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—while Reynaud retained his own place as Président du Conseil. Daladier had fiercely defended his protégé General Gamelin, despite ample evidence that Gamelin had no idea what to do after his Plan D failed, but Reynaud sent him unceremoniously into retirement and replaced him with General Maxime Weygand, who was recalled from Beirut immediately to become commander in chief.

Weygand was reputed to be spry and lively, certainly a big change from Gamelin, but he was seventy-three years old, and his chief claim to fame (apart from rumors that he was the illegitimate son of King Leopold II of Belgium) was that he had served Marshal Foch loyally as his chief of staff for years, the supremely tactful spokesman for a man who spoke as few words as possible himself. As if these changes were not enough, Reynaud also protected himself politically from his enemies on the right by bringing the eighty-four-year-old (and some said senile) hero of Verdun, Marshal Pétain,‡ back from Spain, where he had been serving as French ambassador, to serve in his cabinet as deputy prime minister, a fateful decision for France.

All but the most fervent of the marshal’s admirers thought he was too old, and those in the know believed he was also tired, pessimistic, and deeply Anglophobic. Minister of the Interior Georges Mandel, Clemenceau’s fierce right-hand man, described him as “barely alive—and what there is left is pure vanity.” Nevertheless, Pétain’s belief that France had been drawn into an unnecessary war with a poorly prepared army (thanks in his view to Socialist and Jewish politicians in the thirties) to serve the purposes of the perfidious British, who would let the French do all the fighting and dying, was widely shared, and not just by reactionaries or admirers of Hitler—the commander of the French Navy, Admiral of the Fleet François Darlan, never ceased to remind people that his great-grandfather had been killed by the English at the Battle of Trafalgar.

Marshal Philippe Pétain.

Admiral Darlan.

“Belief” is the correct word—for distrust of Great Britain was part of an ingrained system of belief, beyond mere politics, in which France was always the innocent victim. The Germans, after all, had only made their appearance as France’s enemy in 1870, whereas the English had been fighting France for over nine hundred years. There was no child in France who did not begin to learn French history by hearing the story of Joan of Arc, whom the English had caused to be burned at the stake in 1431.

For a man of his age General Weygand made a remarkable journey in stages from Beirut to Paris seated in a rickety garden chair placed in the fuselage beneath the midships gun turret of a Glenn Martin bomber, which crash-landed on arrival. Weygand had to be “extricated” with some difficulty from the wrecked aircraft, and proceeded at once to pay his respects to the major political and military figures he would have to deal with. He had no immediate strategic solution to the problems facing the Allied armies; indeed when he was shown the position of the armies on a map, Weygand is said to have remarked, “If I had known the situation was so bad I would not have come,” perhaps a sign that already “he was thinking of his reputation” more than of victory.

There was no sympathy lost between Weygand and Premier Reynaud, quite the contrary. Weygand was an unapologetic reactionary, a “political general” rather than a fighting one. Reynaud had picked him, as he had Pétain, in the hopes of disarming his political enemies on the right, and because Weygand had been so close to Foch, perhaps expecting that some of Foch’s fighting spirit might have rubbed off on Weygand, at least in the eyes of the public. If so, he was mistaken.

Joan of Arc.

General Ironside, perhaps embarrassed that he had been sent by the War Cabinet to make Lord Gort attack to the south only to find that he agreed with Gort’s decision not to do so, was astonished to realize how detached General Billotte was from the battle—Gort had received no orders from him in over a week. Taking General Pownall with him, Ironside set off toward Béthune in the hope of finding the elusive commander in chief of the armies in the north, and was swiftly caught up in the chaos of defeat. “The road’s an indescribable mass of refugees,” he wrote, “both Belgian and French, moving down in every kind of conveyance. Poor women pushing perambulators, horsed wagons with all the family and its goods in it. Belgian units all going along aimlessly. Poor devils. It was a horrible sight and it blocked the roads.” He eventually found Generals Billotte and Blanchard at Lens, near the old Vimy Ridge battlefield of the previous war, “in a state of complete depression. No plan, no thought of a plan. Ready to be slaughtered. Defeated at the head without casualties. Très fatigués and nothing doing.”

Ironside lost his temper, shouted at the emotionally exhausted Billotte, and shook him by a button of his tunic to emphasize his points. He must have made an impressive and threatening sight, broad shouldered, nearly six and a half feet tall and powerfully built, as he towered over the two French generals, both of them shouting indignantly back at him, but in the end it produced nothing, and neither did a call to General Weygand, the new commander in chief of the Allied armies, although he promised to come and straighten matters out himself the next day—more than Gamelin had ever done. Ironside returned to London via Calais, where his room at the Hotel Excelsior was struck by a German bomb as he slept, blowing him out of his bed.

_________________________

* To be fair to the Duke of York, he later served for thirty-two years as commander in chief of the British Army, and was an effective, if occasionally corrupt, administrator, though his strongest interests were women and gambling for high stakes.

† Judging from photographs Lord Gort was not so much fat as stocky, tall, and broad-shouldered. He exercised furiously and ate abstemiously in a lifelong effort to control his waistline.

‡ Marshal Philippe Pétain was an immensely popular figure, both for his victory at Verdun in 1916 and for his firm, but relatively humane, suppression of the mutinies in the French Army after General Nivelle’s failed offensive on the Chemin des Dames in 1917. Pétain’s reputation as an indefatigable womanizer did him no harm among the French, either. At one point during World War One, an aide, unable to find him in an emergency, went up and down the corridors of a Paris hotel until he saw the general’s massive boots placed outside a door next to a tiny, elegant pair of women’s high-heeled shoes.