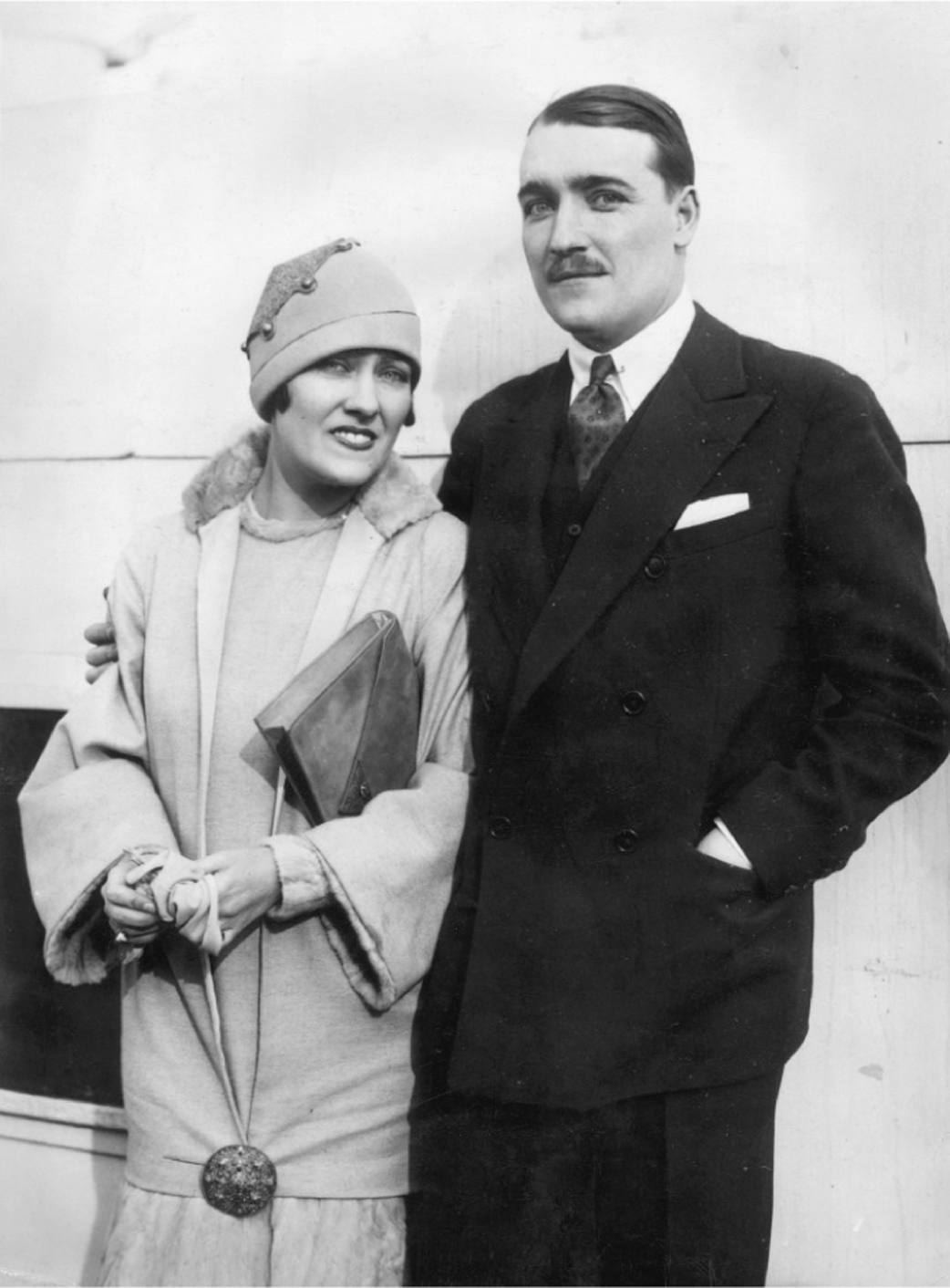

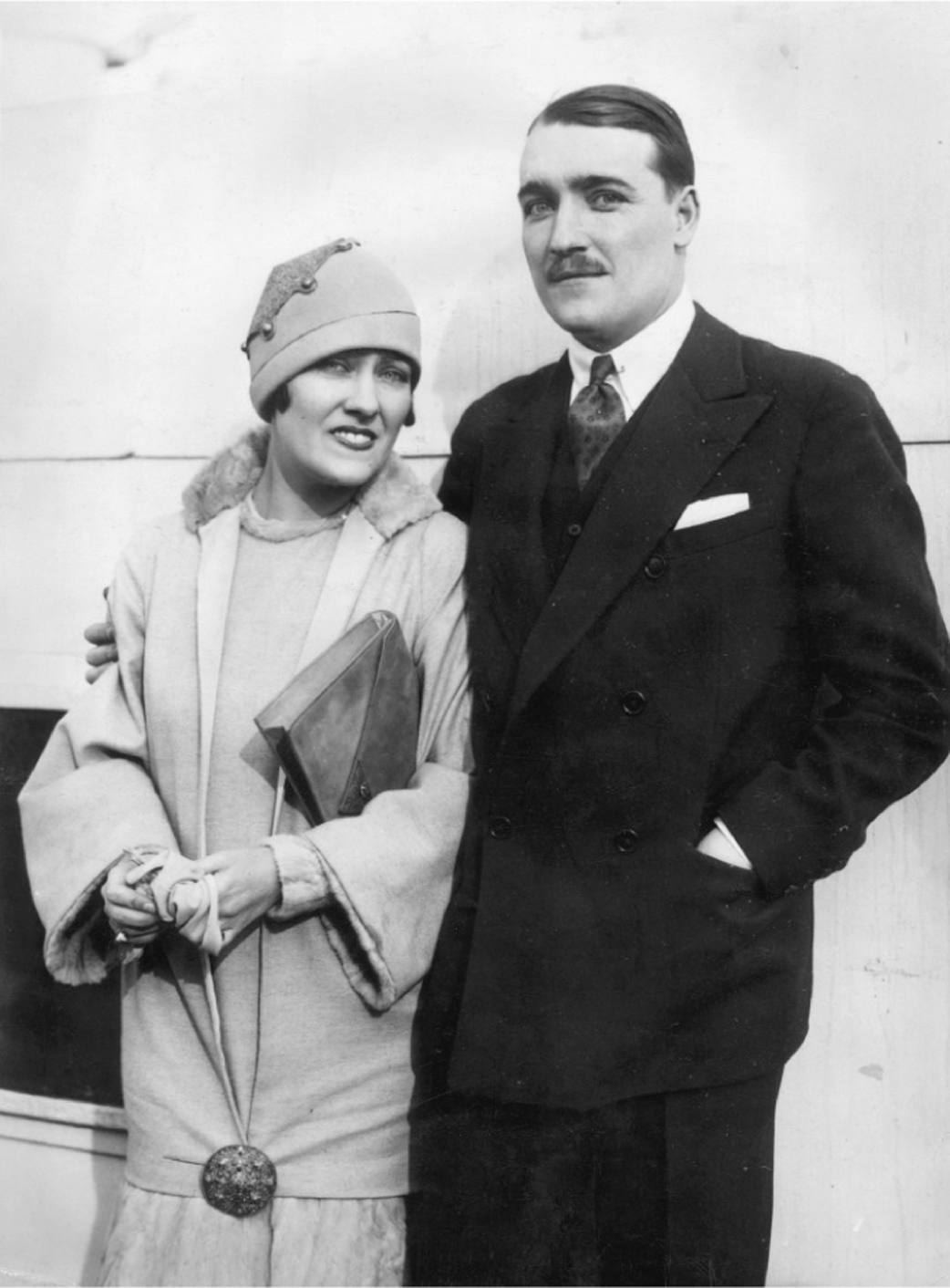

Gloria Swanson and her husband Henry de la Falaise, marquis de La Coudraye.

Gloria Swanson and her husband Henry de la Falaise, marquis de La Coudraye.

THE 12TH (Prince of Wales Own) Lancers had been the first Allied regiment to cross the Franco-Belgian frontier on May 10, 1940, and drive east through cheering crowds toward the Dyle River, which their advance guard of armored cars reached that night—the first step in General Gamelin’s ill-fated Plan D.

Since then, the experience of the 12th Lancers mirrored that of most of the BEF. They had, in the words of one trooper, been “buggered about” for over a week, absorbing as an armored reconnaissance regiment the constant pressure of overwhelming stronger enemy forces, bombed and machine-gunned remorselessly from the air, and obliged to retreat from a line they thought they could have held into the vast chaos of a retreat from one line to the next. They fought to hold every stream, river, and canal along the way, of which there appeared to be hundreds, having been transformed overnight from the proud and dashing advance guard of the British Expeditionary Force into its beleaguered rear guard.

The 12th Lancers was an elite regiment that stood out even in an army full of regiments with long histories, many battle honors, and fiercely defended peculiarities of dress and behavior. Raised in 1697 as a regiment of “light dragoons”* intended to put down a Jacobite rebellion, the 12th Lancers not only fought the French in Egypt and at Waterloo but was honored by George III, who added “the Prince of Wales Own” to its name (after the future Prince Regent and George IV). Its cap badge became that of the three ostrich feathers bound with the Garter from the Prince of Wales’s coat of arms, in addition to which its noncommissioned officers wore three coveted tiny silver ostrich feathers on their sleeves above their stripes. A “regular” regiment, the 12th Lancers surrendered their horses and converted to armored cars in 1928—a big change for a regiment a squadron of which had carried out the last full-scale lance charge in the history of the British Army, on August 28, 1914, at the Battle of Mons. Even in armored cars the officers of the 12th Lancers remained for the most part aristocrats or upper-class sportsmen at ease in the hunting field who prided themselves on their boldness, their stiff upper lip, and their almost feudal relationship with their troopers. Exchanging horses for armored cars had not altered the esprit de corps of the regiment, or its swagger.

Their Morris armored cars were far less well armored or armed than their German equivalents (as well as the French Panhard), basically an angular, clumsy-looking riveted armor-plate shell built on a fifteen-hundredweight truck chassis with an open-topped turret looking like an old-fashioned tin bathtub. It had a crew of three, a driver in a coffin-like armored box, with the commander and the gunner behind him seated side by side in the open turret, armed with a Bren light machine gun and the notoriously ineffective Boys antitank rifle. The Morris armored car had been designed with warfare against dissident desert tribes in Egypt, Iraq, and Afghanistan in mind, not for service in northern Europe against the German Army, and its armor plate would not stop anything much larger than a rifle bullet, but what the 12th Lancers lacked in sophisticated vehicles they made up for with espirt de corps.

Morris armored car.

General Georges had planned from before the war for a high level of integration between the British and French forces under his command. A Franco-British Military Mission of Liaison was set up with its headquarters at Arras, a prosperous and picturesque city in the Pas-de-Calais, close to the Belgian border. Selected English-speaking French officers were trained to accompany British fighting troops at the battalion level, not so much as interpreters merely, but rather as tactful facilitators intended to avoid conflict between British troops and French civilians and to act as the link between French units and British ones when needed. In some cases they rapidly became an integral part of the British unit they joined, despite wearing French uniform.

Belgian civilians fleeing.

The liaison officer chosen for “A” Squadron of the 12th Lancers was James Henry Le Bailly de La Falaise, marquis de La Coudraye, who had joined the French Army while still underage in World War One and been awarded the Croix de Guerre, then went on between the wars to Hollywood, where he directed at least five films and married two major movie stars, first Gloria Swanson, then Constance Bennett. His marriage to Gloria Swanson turned him into something of a worldwide celebrity for a time, since it was the first marriage between a major movie star and a European aristocrat. Immensely handsome and courageous, a “man’s man” to the core, but also notorious as a “ladies’ man” on two continents (Lillian Gish gushed over the sight of him in a bathing suit on the beach at Malibu), Henry de La Falaise (as he was usually known to English speakers) was the perfect choice as liaison officer for the 12th Lancers.† The commanding officer of his squadron was “a high-strung polo player,” a cool gambler, and a natural horseman, and the second-in-command was an earl—La Falaise must have fit right in from the first day.

Fortunately, along with charm, good looks, perfect manners, and guts, La Falaise had an eye for detail, and was in an ideal position to describe the battle as it unfolded. He was on leave in Paris on May 10, but he moved fast. By that evening he had reached Arras by rail, and he crossed into Belgium the next morning. He noted that the Belgian defenses against the French were formidable and difficult to remove once they suddenly became allies on May 10—the Belgians had played the “neutrality card” until the very last moment, perhaps even a moment too long. His journey toward the Dyle River to find his regiment was difficult, involving guile, good luck, and sheer determination. No rail traffic was moving east of Brussels, and La Falaise was basically a hitchhiker in a foreign uniform carrying his own kit toward the front line in search of the 12th Lancers, at a point when wild rumors of spies, German parachutists wearing Allied uniform or disguised as nuns, and “the fifth column” were rife.

Everybody’s memories of the battle in Flanders contain incidents in which innocent civilians, or soldiers in the wrong place at the wrong time, were hastily executed in the panic that followed the German attack. “Better safe than sorry,” was the general opinion in both the British and the French armies, and the safest thing was to shoot anyone who wasn’t attached to a unit, or didn’t have a good explanation for why he was on his own. A man alone on a battlefield is always at risk from his own side. Despite all this, La Falaise reached “the lovely green valley” of the Dyle safely in the late afternoon of May 11 (he seems to have been the only person to remark on its beauty), on the far side of which he at last rejoined his regiment, momentarily stunned by the ceaseless noise of artillery fire and bombs all around him.

When he was sent late that night to make contact with nearby French and Belgian units, his armored car was halted by “the flow of fleeing humanity . . . I can hear frantic screams when bombs plaster the road ahead . . . accompanied by the crash of nearby explosions and the bleating and mooing of the terrified farm animals.”

The speed of the German advance was such that civilians suddenly found themselves engulfed in the combat zone and left their home or farm in panic—the first wave of a flood that within the next few weeks would put millions of people in Belgium and France on the road. The Germans contributed to the panic both as a matter of military policy—Schrecklichkeit, or sheer frightfulness, has always been the fallback position of Germany toward its enemies—and because the refugees unwittingly blocked the lines of communications of the Allied armies. The Germans bombed and machine-gunned the refugee columns mercilessly, which of course added to the panic, spreading fear far and wide and thus setting more people in motion. The burning of Belgian villages and the bombing of Belgian towns was carried out with the usual German thoroughness, reinforcing the impulse to flee. People set out with all the possessions they could carry, farmers even drove their own livestock before them (after all, they were a farmer’s most important possession), while livestock left behind went unfed, unwatered, and unmilked, adding their cries of pain, complaint, and fear to the misery that was rapidly engulfing this peaceful, prosperous, rural corner of Western Europe.‡

The fact that the Allies were withdrawing does not mean they were not fighting. Gamelin’s plan to hold a line on the Dyle quickly collapsed, partly because the Germans were moving too quickly to permit drawing a fixed line against them as he had intended, partly because he had not allowed for the overwhelming effect of German air superiority and the accuracy of the Stuka dive-bombers, nor for the collapse of Dutch resistance in only five days, but La Falaise’s account of the next week of battle is a constant succession of intense firefights and soaring casualties, none of which seem to have dampened his spirits, or his uncanny ability to find freshly baked bread, wine, and cheese in the most unlikely places. By May 12 the 12th Lancers were about fifteen miles east of the Dyle River, the line on which the Allied armies were still assembling—and which, if they could hold it, would theoretically protect Brussels and the great port of Antwerp. They were about twenty miles southeast of historic Louvain, home of the famous university and its library, which the German Army had razed to the ground in August 1914, an act of vandalism that had shocked the world—and that the Germans were about to repeat.

In this tiny triangle of what is in any case, even for Europe, a small country, the Germans concentrated a devastating nonstop air assault, completely destroying countless small towns and villages. The Luftwaffe was virtually unopposed—the Belgians had no modern antiaircraft guns, the French and the British had not brought theirs forward yet, and the bulk of the RAF in France and what remained of the French Air Force was in action a hundred miles to the south, attempting to slow the German breakthrough from the Meuse to the west. The Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers, with their slow speed and fixed undercarriage, were easy prey for British fighters, but in the absence of these—and aided by perfect weather—they flew in large formations and peeled off one by one to dive-bomb every target they could see, with remarkable precision.

“The Stuka was the sharpshooter among bombers,” recalled one of the Stuka pilots, and British troops soon learned the importance of camouflaging every vehicle and gun, and of not concentrating at crossroads or in village squares. From a thousand yards up in good weather a Stuka pilot could see even the smallest sign of a potential target: puffs of dust raised by a vehicle on country roads or lanes, tracks of motorcycles and armored cars leading to cover in a wood or a farm, a carelessly placed cook stove, the barrel of an antitank gun sticking out of a hayrick leaving a telltale shadow, or a flash of sunlight from a pair of field glasses carelessly handled.

Soldiers eventually hardened to the infernal noise the dive-bombers made—in addition to the sirens below their wings, they had whistling fins on their bomb—and soon grew to accept the eerie sense of vulnerability that came from a sudden attack from the sky. A private of the 5th Border Regiment recalls jumping headlong into a filthy ditch for cover as he heard the noise of a Stuka diving, just beating a civilian to it as the bomb fell. When he stood up after the explosion, he saw an object rolling toward him across the road. “Who the hell is playing football at a time like this?” he thought, only to realize that what he was looking at was the civilian’s head.

The first encounter of Allied troops with the enemy was usually the approach of a German advance guard of motorcycle troops coming down the road toward a bridge or village that was being held. Their motorcycle battalions were equipped with a high proportion of machines that had a sidecar for a gunner with a light machine gun. At the first sign of opposition the motorcycle troops dismounted and spread out under the cover of the light machine guns. If they could, they stormed the position, if not they sent a motorcycle messenger back to alert the tanks and armored cars behind them, with infantry in trucks and towed artillery behind them. If the opposition was more serious than they could overcome, air support was called in, either from Stukas or flights of twin-engine Heinkel 111 bombers, which flew straight and level and carried a heavier bomb load, enough to obliterate a small village. On both sides, casualties among motorcyclists were high—at a range of one or two hundred yards a man on a motorcycle is an easy target for a competent marksman, and standards of marksmanship in the British regular army were very high indeed. As for the British, almost every account of the fighting mentions dispatch riders lying dead or dying beside their machine, since the British relied on them to carry messages rather than on their relatively unreliable radios, and a man on a motorcycle presented a perfect target for the gunner of a low-flying Stuka or for German fighters.

Careful and detailed as Plan D was—and General Gamelin’s staff had almost two years to perfect it—it still relied on wild overestimates of the tenacity and duration of Belgian and Dutch resistance, and on the belief that however quickly the Germans attacked initially they would sooner or later be stopped by a fixed line as in 1914–1918. The notion that Army Group B might get to central Belgium in strength before the Allied armies could even prepare a fixed line had been excluded from Gamelin’s plan.

The experience of the 12th Lancers was typical of the bloody fighting that took place in the days that followed the German attack. The regiment moved well forward, nearly twenty-five miles east of the Dyle River, one troop holding “a small bridge on the River Gette, north of Tirelemont,” with a Belgian division “fiercely engaged” on their left and a French division légère méchanisée§ (light armored division) heavily engaged on their right. The next day, La Falaise was ordered to drive forward with “the fighting lorry” (a truck carrying cans of gas and ammunition, a dangerous task) and after being machine-gunned by three Stukas firing from six hundred feet above him, managed to reach the point where one troop of the regiment’s armored cars was holding a railway bridge across the Gette. The Germans were concealed in a line of trees about a hundred yards away, and had already managed to get a few machine guns across the stream, although not without suffering some casualties. “Three wrecked German motor cycles and six dead bodies [lay] sprawling on the mud thirty yards ahead,” as La Falaise and his friend the troop commander exchanged pleasantries under fire while watching German aircraft bomb a nearby village. By the evening the Belgian troops began to withdraw, and “loud explosions rock the earth as the Belgian ammunition dumps a mile away are blown up.”

By nightfall the armored cars of the 12th Lancers were ordered to withdraw to the highway leading to Louvain. “An appalling sight greets us there. Enemy bombers have reduced this wide and lovely road to havoc and desolation. Trucks, large passenger buses, private cars, some still on fire, are strewn over it. One huge holiday bus has been blown up beside a wrecked house, its front wheels resting on what remains of the roof. It is still flaming like a gigantic pyre, casting a red glow on the pools of blood and the mutilated bodies which are lying about it.”

The Belgians have come in for a bad press in history (and in the memoirs of British soldiers of every rank) since 1940 for fighting poorly and surrendering too quickly, but La Falaise captures in his narrative the terrible destruction caused by the German attack on a small, unprepared neutral country—a neutrality that had been solemnly reconfirmed by Germany as recently as October 1937. In 1940 as in 1914 Germany simply ignored Belgian neutrality, and rained death, destruction, and savage “reprisals” on the Belgian people, whose only offense was geographical: their country stood in the path of the German attack against France. The notion that both the Allied and the German war plan had transformed Belgium into the fighting ground for a major battle, and that every time the Allied forces “pulled back” or “withdrew” they were leaving part of Belgium to the untender mercy of the Germans was not one that was likely to inspire Belgian morale.

Later that night La Falaise reports more bad news—the two French DLMs to the south are falling back, taking (and possibly inflicting) heavy casualties, and the 12th Lancers are ordered to “retard” the enemy as long as possible. La Falaise takes shelter from a bombing attack in the cellar of a burned-out house, feels the presence of somebody beside him in the dark, turns on his flashlight and discovers “the mangled body of a woman, lying in a pool of coagulated blood a few inches from [him]. Her left leg is cut off from the thigh down. . . .” He stumbles over her leg as he leaves the cellar. At dawn he and the rest of the 12th Lancers stand in silent awe as wave after wave of German bombers methodically destroy Louvain again—rebuilt by innumerable donations from all over the world after the end of the First World War—the “ancient buildings fast becoming piles of stone and rubble . . . under a thick cloud of black smoke and dust.”

By the evening of May 14 the 12th Lancers were back on the west bank of the River Dyle, only three days after they had crossed it, getting over the bridge just before the Royal Engineers blew it up, taking a platoon of German motorcycle scouts with it. In full keeping with the traditions of the British Army, La Falaise’s friend Lord Frederick Cambridge (a member of the royal family, he being the nephew of Queen Mary, widow of the late King George V), a captain in the Coldstream Guards, sent him a bottle of “old brandy” by dispatch rider, with a note explaining that he was too busy to share it—Lord Frederick was fighting in the ruins of Louvain, where he would be killed the next day.

The following few days passed in an exhausted blur of bitter fighting, through one destroyed town after another. Caught up in the bitter, nonstop fighting around Brussels, La Falaise does not hear until May 16 about the German breakthrough farther south at Sedan, by which time he has been on his feet (and in his boots) for four days and nights, so the bad news scarcely makes an impact on him. On May 18 La Falaise learns that Brussels has fallen, and that the Allied armies are withdrawing to the Dendre River, with the 12th Lancers again forming part of the rear guard. Their fighting retreat takes them from the battleground of Waterloo to the sites of many of Marlborough’s battles in the seventeenth century, and past some of the British Army’s most terrible battles in World War One. It is as if this tiny patch of Belgium has been fought over for three centuries, and it is hardly possible to travel more than a few miles without seeing neat rows of British graves. Along the way the 12th Lancers continue to lose men and armored cars, pause to bury their dead, and move on.

La Falaise describes a typical moment, after a bombing attack:

A bright orange flame blinds me and a number of earsplitting explosions lift the car. . . . The armored car which was ten yards ahead of us, is on its side [now] in a deep gully. . . . For five minutes, we dig and push while another armored car skids and tugs at its bogged-down mate. . . . Our work is made more difficult by the constant attention that two bombers are showering on us in the shape of short bursts of machine-gun bullets. . . . My shirt and tunic are soaked with sweat from heat and fright. . . . Andrew, [the troop commander] who has worked twice as hard as any of us, finally straightens up and calls the whole thing off. All equipment and weapons are removed and the Major himself ends the life of the armored car with his own pistol, shooting the engine full of holes.

That night they “tear down the highway at full speed . . . passing bodies, wrecked cars and flaming farm houses,” cross the Dendre River, and then drive on to lager for the night at Buissenal, about two-thirds of the way between Brussels and the Franco-Belgian border.

“The Major’s voice giving orders to the squadron arouses me from my slumber,” La Falaise writes, “I look at my watch. I have slept ten minutes!

A small girl has just entered the kitchen. She has immense dark eyes, thick, curly, black hair and her skimpy pink dress is crumpled and soiled. She holds an infant in her arms and she begs for a little milk for the baby, her brother. I want to go back to sleep, but there is something so appealing in her quiet, assured, older-than-her-age tone of voice that I can’t help watching her. Her right shoe is split open, her feet are swollen and sore and, while the milk is being made warm, she sits up very straight on a chair with the baby on her lap and tells me her story.

She has walked all the way from Brussels, forty miles, in a day and a night. She is eleven years old. Her parents, German Jews, used to live near Berlin, but they had to flee when the Nazis came to power, and settled in Brussels. Soon they found jobs and things were beginning to look brighter. Then came the baby brother, the war, and the invasion. Once more they fled. She tells me that her mother and father are sick and that she has left them lying on some straw in a barn nearby.

I can see that she has serenely taken upon her frail shoulders the whole responsibility for the family. She wants nothing for herself, only for her father, her mother, and the baby. Her only hope, her goal, is the frontier of France. She seems to feel that if she can get her family across the border they will be safe forever. She knows that they have over thirty miles to go, but she is a most amazing small person, in her absolute certainty that the Allied troops are to stop the Germans—at least long enough for her to get to the border. I do not contradict her.

She asks me if I think it will be safe for her to lie down and rest for a few hours. “Because you see,” she adds, “I am very tired, and my feet are very sore.”

I promise her that I won’t let her oversleep and will wake her up before we leave which will certainly be early in the morning.

The kind-hearted woman who owns the farm and who has overheard our conversation brings some hot water, a basin to bathe the child’s feet and also gives her a pair of rubber sneakers to replace her worn-out shoes. Our cook makes sandwiches for her and her family, and, as the brave child leaves the kitchen, she thanks us with exquisite politeness and, with the dignity of a queen, solemnly steps out into the dark night holding her tiny baby brother in her tired, aching arms.

I follow her to the door and watch her as she crosses the courtyard and enters the straw-filled barn. As she walks away in the night, she suddenly seems to grow in stature and embody the spirit of her persecuted people as well as the undying determination of the human race to live on. And I suddenly feel ashamed of my weariness.

A radio operator brings us orders. We are to leave at 3.00 A.M., returning to the Dendre River to try to hold the heights above Lessines while our infantry withdraws.

There isn’t an unoccupied square foot of flooring anywhere in the house on which to lie down and sleep; all the rooms are filled with refugees. So I roll up in my blanket under a damp pile of hay in the orchard.”

La Falaise, perhaps because he is a European, has a sharper sense of what is in store for the young girl than his British fellow officers do. He knows that behind the German armies will be coming the Gestapo, the Sicherheitsdienst, and what Winston Churchill called “all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule,”¶ and that German-Jewish refugees, along with anti-Nazi Germans, will be among the first to be swept up and removed to concentration camps. He can do nothing for the young girl, he cannot take her, the baby, and her family in one of the 12th Lancers armored cars, and perhaps he has already guessed at some level what is likely to happen to them all once they are back in German hands. La Falaise is describing a tragedy within a larger tragedy, a tiny fragment, a sliver of the vast misery and suffering that is being unleashed on Western Europe. The frail Jewish girl in the pink dress holding her baby brother is both a symbolic and a real victim of French and British diplomacy in the thirties, of appeasement, of rearmament too long delayed, of American isolationism, of mistaken strategy and worse tactics. He sees her one last time, in a crowd of refugees pushing a baby carriage with one broken wheel toward France, surrounded by a vision of hell: “The road is a mess. Huge trees blasted by bombs, wrecked cars and transport buses riddled with bullet-holes bar it at several points. The bodies of disemboweled horses have been blown up on the embankments, and in several places men’s bodies lie mangled and bloody in the dust. Straight ahead the smoke column rises ever blacker and thicker and bright red flames leap skyward over Tournai.”

La Falaise is on his way in the staff car to scout the ruins of Tournai for the regiment, where he finds that every house is scorched and empty, the library is in flames, and the streets are blocked by live wires from overturned trolley cars, and by rubble. He cannot stop to speak with the little girl in the pink dress. There will be no Dunkirk for those like her.

By May 20 the 12th Lancers have crossed the frontier back into France only to learn that Arras, which just ten days ago was the headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force and of the Franco-British Military Mission of Liaison, is already under attack by German tanks, and a plume of smoke rises from the city. Just a few miles from Arras, La Falaise’s armored car is halted at a level crossing by a massive traffic jam caused by French artillery moving south while French infantry in trucks is moving north—a symptom of the collapse of the French command and control over the battle—and he discovers a dejected railway worker staring at a huge, overturned locomotive blocking the tracks. La Falaise asks why nobody is trying to clear the railway line. The railwayman “answers with a shrug: ‘What the hell is the use? Les Boches have cut the line south of Arras.’ ”

For the first time, La Falaise realizes the full import of what has happened. “The long, steel cord which joined us to the heart of France,” as he describes it, has been cut, the German breakthrough from the Meuse at Sedan has severed the connection between the French armies in the north and the bulk of the French Army to the west and south, leaving the BEF with no place to go but the sea, and stranding what remains of the Belgian Army in a tiny corner of northwestern Belgium.

Ordered to proceed toward Arras and see whether it is in German hands, La Falaise observes vast clouds thrown up by the long columns of refugees, French now, instead of Belgian, then realizes that the Germans are using the dust clouds to slip tanks in among the fleeing civilians and their cars, carts, and horses. The sound of a massive artillery barrage and bombing proves that Arras is still holding out, but then a German tank opens fire, punching a hole in one of the troop’s armored cars, wounding one of its crew and killing another, and by the late afternoon the troop pauses, not far from Arras, to bury its dead in a “quiet pasture, surrounded by thick green hedges . . . reminiscent of an English landscape.”

Settling down to defend a village for the night with some French armored cars of the 1st Cuirassiers,# La Falaise learns that the French 1st DLM has experienced “staggering” losses, and over 80 percent of its tanks and armored cars have been destroyed. As for news from the world outside, the rumor is that General Gamelin and General Corap, commander of the French Ninth Army on the Meuse, have committed suicide. While nobody seems to believe this rumor, which was in fact untrue, the general feeling of the Cuirassiers officers is that they ought to have done so, given what a mess they have made of things.

By midnight they receive orders to take part in a last-ditch attempt to relieve Arras, which is visible in the dark as a vast, glowing fire on the horizon.

_________________________

* “Light dragoons” evolved into hussar and lancer regiments and then were converted into light tank or armored car regiments.

† His father won three Olympic gold medals for France as a fencer, and his niece would become the famous Loulou de La Falaise, fashion icon, much photographed beauty, and muse of the fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent.

‡ Part of this was merely the immemorial cruelty of war, of course. The Allies too placed artillery batteries in orchards that had been lovingly tended for generations, parked tanks and armored cars in barns and stables to hide them from the German bombers, ransacked and looted abandoned homes, etc., but they did not deliberately bomb and strafe vast numbers of fleeing civilian men, women, and children or, at this stage of the war, target for bombing towns and cities of little or no military importance.

§ These were not the equivalent of a German panzer division. They constituted basically infantry divisions in trucks, with elements of tank and armored car units attached to be used to support the infantry. Their purpose was defensive, not offensive; they were incapable of the kind of long, sweeping breakthrough being carried out by the divisions of Panzer Group Kleist to the south.

¶ House of Commons, June 4, 1940.

# Cuirassiers were elite “heavy cavalry,” wearing breastplates, brightly crested metal helmets, and thigh-high boots, like the Horse Guards in Britain, now converted to the “armored role” of tanks and armored cars.