British machine gunners in the streets of Dunkirk.

“Fight It Out, Here or Elsewhere”

British machine gunners in the streets of Dunkirk.

NO NEWS OF these massacres reached Britain, of course, or even General Lord Gort’s headquarters. Communications between units of the BEF had broken down, and communication between the BEF and London was reduced to faint and unreliable telephone calls. All that was known was that the army was falling back on Dunkirk.

In London no hint of the disagreement in the War Cabinet on May 27 reached beyond the small circle of those who were close to its members. Churchill’s private secretary John Colville was near enough to his new boss to note that “there are signs that Halifax is being defeatist,” but even Churchill’s old friend and confidant Lord Beaverbrook, owner of the Daily Express and the Evening Standard, who was certainly aware of everything that went on in the War Cabinet, was careful not to leak a word of what was going on. More people in Rome or Berlin knew of the rift between the prime minister and the foreign secretary than did people in London. Of course in Rome and Berlin they hoped that it was an old-fashioned “cabinet crisis,” and that Halifax had weighty support in the War Cabinet, but in fact he had none—his doubts were personal and moral, or perhaps philosophical, and were not even shared by former prime minister Neville Chamberlain, now lord president of the council, whose detractors still spoke of him disparagingly as “Old Umbrella.”

Chamberlain had reverted to the tough-minded, hard-nosed politician he had always been before being led down the garden path of appeasement, and showed little sympathy for Halifax’s proposal to let the French find out what Hitler’s terms might be for peace, preferably with honor if that were possible, and still less for giving in to French demands for more fighter aircraft and British troops. Possibly Chamberlain’s experience of having Daladier as a partner during the Czech crisis—playing Sancho Panza to Chamberlain’s Don Quixote—had soured him altogether on France, but he now appeared as the apostle of realpolitik. In any case he had never cared much for the French, even less for the Czechs, the Poles, or for that matter the Germans, whether as represented by Hitler or otherwise. He was mildly interested in foreign policy, but disliked foreigners, a very English point of view. Improbable as it seems, Chamberlain was now a full supporter of Churchill—he brutally dismissed French claims to have been deserted by the British, and disparaged French accounts of how hard they had fought. He offered little support to Halifax; indeed one has the impression that he had hardened within his carapace like certain sea animals. Certainly Hitler was mistaken if he supposed that a full-scale cabinet revolt was brewing—so far it only consisted of one man, battling for Churchill’s soul, or his own. Still, that might have been enough, had Dynamo failed.

As yet, however, Dynamo had not even begun. The public had not been prepared for bad news—indeed the daily communiqué from the GQG in Vincennes remained improbably “cheerful” in tone and optimistic, in contrast to the real state of events, let alone the state of mind of General Weygand, Premier Reynaud, and the rest of the French government. The Times for May 28 passed on the official GQG view of events via the Ministry of Information with this headline: “B. E. F. FRONT REMAINS INTACT, COOPERATION WITH FRENCH TANKS,” and repeated an old bromide of World War One, “The French, after twice repulsing the Germans at Valenciennes, have withdrawn to previously prepared positions,” a euphemism older readers who had lived through the First World War would remember for “headlong retreat.”

The more popular newspapers speculated that the Germans had already sacrificed nearly half a million men in suicidal attacks, possibly as many as 600,000, as well as most of their aircraft. In fact, the Germans suffered a total of about 150,000 casualties, of whom about 27,000 were killed, during the entire campaign from May 10 to the surrender of France, and the Luftwaffe more than made up its losses in aircraft. The gap between reality and the official French military communiqués had become so alarmingly wide that Minister of Information Duff Cooper was worried that the British public “were, at the moment, quite unprepared for the shock of realization of the true position.” To that view Churchill sensibly replied that the announcement of the Belgian surrender “would go a long way to prepare the public for bad news.”

In fact, most people in Britain were not nearly as misled as their leaders supposed them to be. They drew their own conclusions from the maps in the newspapers, which made it clear that the BEF was surrounded with its back to the sea, as well as from an instinctive mistrust of the French and, at least in southern England, from the sight of “small ships” and even small boats being gathered rapidly in familiar rivers and harbors.

The Ministry of Information was still combining patriotic propaganda with the kind of wildly improbable stories in the old Fleet Street manner so richly caricatured by Evelyn Waugh in Scoop, like that of a couple of unarmed Auxiliary Army Pioneers (pick-and-shovel men) who put two German tanks out of commission with their picks, then took the crews prisoner. Perhaps out of a sense of its own dignity the Times did not stoop to explain how to stop a tank with a pick, although the eminent literary critic Cyril Connolly fiercely caricatured the story in “How to stop a tank”: “If you are very close, insert a knitting-needle into the tank’s most vulnerable spot, the back-ratchet.”

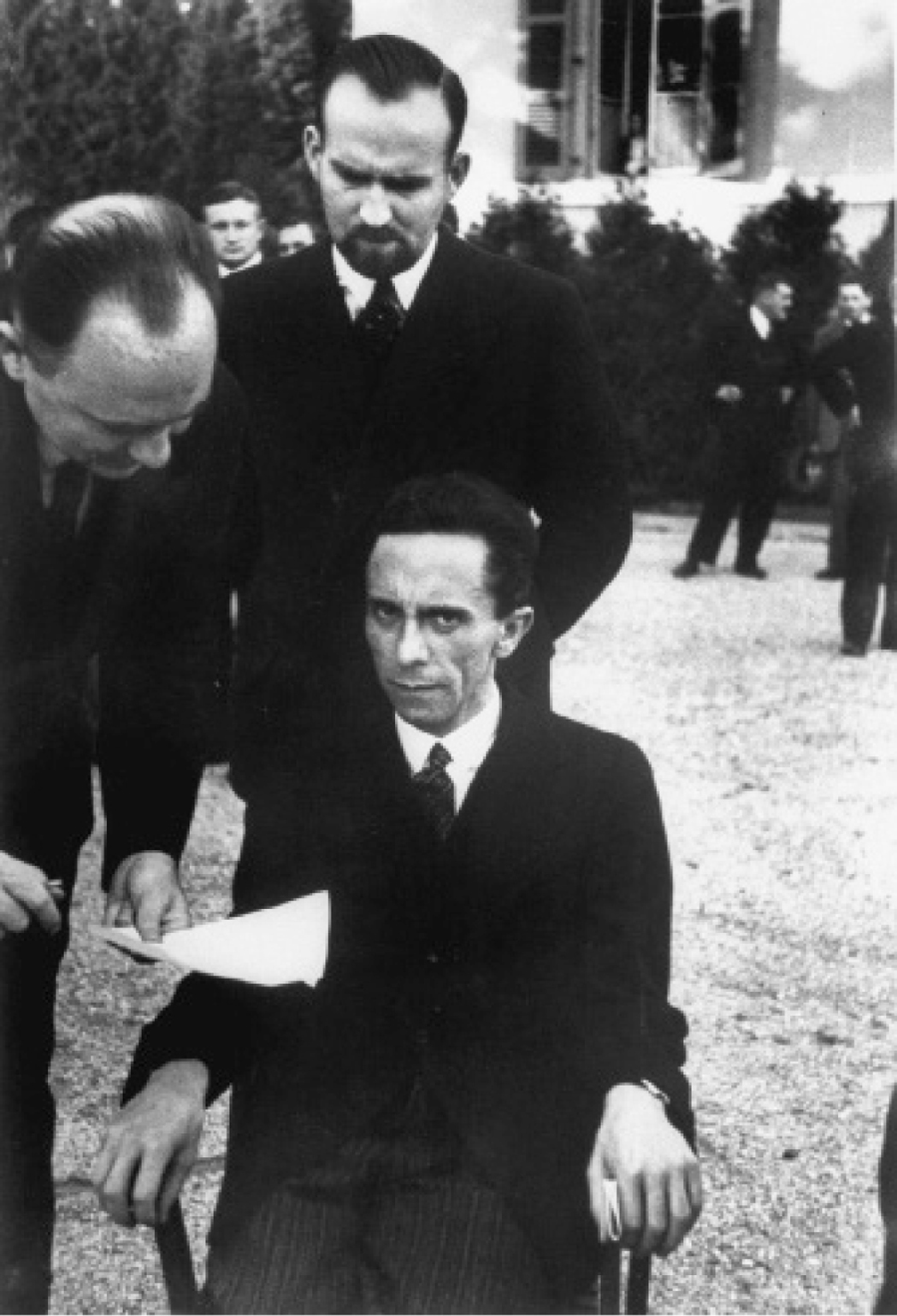

Dr. Joseph Goebbels, Reich minister of propaganda, having just been told that the person taking his photograph is Alfred Eisenstaedt, of Life magazine, a German Jew who had emigrated to the United States.

Traces of this head-in-the-sand news policy would continue to surface in the press for some time, but eventually Churchill managed by his own gift for oratory and for dramatizing the historic moment to make the British public feel not only good but heroic about bad news,* something that Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels never dared to try with the German public until it was too late.

At home in Hampstead my father looked increasingly grim, as well he might—a survivor of the collapse and surrender of the Austro-Hungarian Army in 1918, he recognized the signs of military disaster, however well disguised with Schlag,† better than most. The Austro-Hungarian Army in 1918 had “withdrawn to prepared positions” until it simply disintegrated, like the empire itself. At least its soldiers could march back home to Vienna, Budapest, or Prague, rather than to a beach. At the studio in Denham Vincent was surrounded by huge sets he had designed for films that could no longer be made there, and as his men were withdrawn into the armed forces or the weapons industry, the cavernous soundstages were silent and empty. Whatever his reluctance was, he must have known by then that he was going to have to fit into Alex’s plans.

He was not, of course, about to share these with me. Like so many children in England at the time, most of them far less fortunate than myself, I was about to be packed off in a hurry to places unknown. All over the country people were abandoning homes and families, children, pets, and cherished possessions, to undertake new and unexpected responsibilities, often in faraway places. Men younger than my father were “joining up”; indeed one of his assistants had already left to join the Royal Air Force. Men of my father’s age and older of a certain class were being drawn away by one of the many mysterious organizations that had proliferated in London since the beginning of the war and were identified, if at all, only by odd initials like SIS or SOE.‡ My father had been eager to do his bit for his adopted country, and was interviewed for some hush-hush military job involving camouflage—which, as a painter and scene designer he would have been very good at—but the last question at his formal interview, put to him by a senior officer in uniform, was whether he would be willing to learn how to ride a motorcycle, to which he very sensibly said no.§ My father was then forty-three years old, and anybody who had ever seen him struggle with a motorcar would have realized that there was no chance at all of his being able to ride a motorcycle. It may also be that my father’s appearance, with his scuffed shoes, suit jacket with the buttons in the wrong buttonholes, and unpressed trousers, had something to do with it, or perhaps his thick Hungarian accent. It would have been hard to imagine him in British uniform crisply returning salutes.

In any event, Alex’s needs, as always, took precedence over his own, even when it came to serving his country, so there was no chance of his getting into uniform. If Alex’s films could not be made at Denham, then they would have to be moved to where they could be made, and that was that. During April and May 1940 as the war began to escalate, Alex flew back and forth between London, New York, and Los Angeles at a time when this was neither safe and easy nor possible at all without a high government priority. He returned to London on May 17 via Tangier and soon met with his old friend Minister of Information Duff Cooper, who gave him Churchill’s blessing for making That Hamilton Woman in Hollywood—a bold move intended to make it seem that the film was a big-budget American production, as opposed to just another British propaganda film. This was made more plausible by the fact that Olivier and Leigh were each just coming off a huge Hollywood success, he in Wuthering Heights, she in Gone with the Wind, and would have been treated as “bankable” stars by any Hollywood studio.

One might suppose that a man faced with the possible loss of the lion’s share of the British Army followed by a German invasion would have other things on his mind than the making of a movie about Nelson and Lady Hamilton, but one of Churchill’s most remarkable abilities was his determination to control every aspect of the war, down to the most minute details. Although business leaders are constantly advised to learn how to delegate, the four world leaders in the Second World War shared a passion for detail. Hitler reached the point where he was moving about mere battalions, Stalin spent hours reading through the lists of people condemned to be shot, initialing or countermanding every name with a sharp red crayon, and FDR had the memory of a computer when it came to politics.

Of them all, Churchill’s interests were the most widespread, and from the very beginning of his prime ministership he sought to review and control every decision. When something drew his attention, he was unflagging in his determination to see it done the way he wanted it to be, from the dinginess of the Admiralty flag, which caught his eye, to the casting of Alex’s film and the importance of launching it as an American film, not a British import. It was not just that propaganda, as Alex put it, needed “sugar-coating,” in order to affect American public opinion; it also needed to sail under the American flag, not the Union Jack. Every effort was made to make That Hamilton Woman seem like a big Hollywood romantic drama, one that just happened to be about a British subject (so, after all, were Wuthering Heights and Rebecca).

My father had no particular desire to leave England for Hollywood, and anyway crossing the Atlantic for the moment was far more dangerous than being in London. Asked years later how he had felt about leaving for Hollywood at a time when many people expected an invasion, my father merely shrugged—he had done what Alex wanted him to do, and Alex had done what Winston Churchill wanted him to do, and that was that. When Alex and my father returned to Britain in 1942, they were briefly criticized for being “homing pigeons,” as those who returned from Hollywood once the danger of invasion was over were called. (They included Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, among many others, as well as Alfred Hitchcock.) My father, puzzled by their accusations, told a meeting of angry British filmmakers, “Please, vat is all this talk about ‘homo-pigeons?’—at which point the meeting broke up in helpless laughter. Alex was knighted, the first film knighthood ever, and he and my father stayed on in London making films despite the bombing, the German “doodle-bugs,” and the V-2s. Alex’s house on Avenue Road was bombed, as was ours on Well Walk. My father never felt any degree of shame about leaving when he was told to. If asked about it in his old age, he would stare into space for a moment as if looking for Alex, then sigh and say, “Ah, vat the hell, all zat vas a long time ago.”

Of course “all that” was still a long time before us on May 28, when the fate of the BEF was added to my nightly prayers, a sign that by then even Nanny Low, despite the best efforts of the Ministry of Information, understood that the BEF was in grave danger. I am guessing that several million other children in the United Kingdom also added the BEF to their nightly prayers about then. Even the sturdiest of optimists felt by now that it would take a miracle to save them—and, being British, assumed that God would provide one.

I know it was May 28 because that was my grandfather Ockie’s birthday, in honor of which I was shepherded downstairs before going to bed to call him in Hendon and wish him a happy birthday—in those days it was an unusual thrill for a child of seven to make a telephone call, since the telephone was an instrument strictly for grown-ups, heavy and black, not at all like the bright, flimsy ones today. Ours sat on an antique side table in the hallway, and in the evenings my father was often obliged to take his glass of red wine out to the hall and stand there talking to one of his brothers in vehement Hungarian at great length. God only knows what the people who monitored overseas calls made of these long calls in Hungarian! Every so often one overheard a word or two in English, “dollars,” “pounds,” “Hollywood,” and names of course: “Larry,” “Vivien,” “Ralph,” “Orson,” “Selznick,” “Louis B. Mayer,” and many more, sometimes even my own name, “Miki.” Vincent made many calls to Los Angeles, a major undertaking in those days, to reach Zoli, the middle Korda brother, who had already made the trip to America with his wife and two small children. Afterwards my father would come back to the dining table, pour himself another glass of wine, and say, “Vat the bloody hell.”

He never explained what the subject of the conversation had been—it was understood by everyone, even my mother, that anything said in Hungarian was none of our business, and also that asking about it would be pointless.

I duly wished my grandfather a happy birthday—he was always genial, kind, and slow-spoken, even on the telephone. Except for film people like my uncle Alex and my father (and theater people like my mother), most people tried to keep their telephone calls short in those days. Chattering on the telephone was considered wasteful and extravagant to begin with, and in any case the lines were supposed to be kept clear as much as possible for official use. But Ockie never hurried; he had the kind of warmth and old-fashioned courtesy that must have put all his patients at ease, even though he still used a foot-powered dentist’s drill, and extracting forceps that looked like something that might be used on a horse, and he always sounded genuinely interested even in what a child of seven had to say, which not many people are.

Afterwards I was taken upstairs to the “nursery,” where I had my supper, brushed my teeth, then got down on my knees to say my nightly prayers, over which Nanny Low usually presided sternly, arms crossed over her ample bosom, to make sure I went slowly and didn’t leave out anything or anyone. This night, however, she surprised me by getting down on her “poor old knees” (as she always referred to them) beside me and told me to pray with her “for the safety of the British Army in France.” Her own palms were pressed tightly together, and there were tears in her eyes behind her gold-rimmed pince-nez. She usually said her prayers long after I had said mine and gone to bed, and she had so far as I know no relatives in the BEF. It was nothing personal—it was as if the whole nation were, for a brief moment, united in anxious prayer or, for those who did not pray, in silent thought.

I did not picture in my mind our army on a beach. That idea had not as yet occurred to anyone except Admiral Ramsay—the idea was still to remove as many of them as possible from the port of Dunkirk, just as the German idea was to bomb the town and port day and night to prevent their evacuation. Getting fifty thousand of them out, Admiral Ramsay still thought, would be a triumph.

The next twenty-four hours would change that picture dramatically, to everyone’s surprise.

Dunkirk was already a shambles. Bombing had shattered the town and set the inner docks on fire, as well as the numerous oil storage tanks of the big refinery to the west of the harbor, which would burn without letup for the next week, blackening the sky by day and producing a vast eerie orange glow, visible for miles, by night. Dunkirk already had “the stink of death. It was the stink of blood and cordite,” according to one British soldier who passed through it. Those who were there never forgot the choking stench of burning fuel oil and the pall of dense oily smoke that blackened everything and filled the lungs, mixed with the nauseating smell of decaying bodies and burning gasoline and rubber as the British set fire to thousands of vehicles to prevent their falling into enemy hands. (Even so, photographs of the German invasion of the Soviet Union a year later show a surprising number of British Army Bedford lorries.)

The streets were full of rubble and broken glass, and there was inevitably a certain amount of looting and indiscipline—many of the troops had been on their feet, without sleep for three days or more, under constant fire, and not a few had lost their officers. The civilian population of Dunkirk had fled, or was dead or in hiding, the contents of houses and shops blown into the streets. The water plant had been destroyed, and such water as could be found was contaminated by raw sewage—thirst, rather than hunger, was the first thing that every survivor remembered.

Many of the rear guard had no idea of where they were retreating to, still less of the plan to get them home. They were in constant contact with the enemy, marching by day, digging foxholes for the night. Jack Pritchard, a guardsman of Number 4 Company, 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards, describes what it was like for the troops:

We found the roads in chaos, as constant shelling had brought down telephone and electricity poles. . . . We formed into columns of three and began to march. No-one was aware . . . of our destination. Hour after hour we marched. The journey continued, with only a few minutes break every hour, for the tired troops to relieve themselves, or to have a drink from their water bottles. . . . Men grew listless, and spoke very little, automatically marching in step. . . . Occasionally a guardsman would weave off to the flank, half asleep or suffering from dehydration. His weapons and ammunition would then be distributed among his comrades, and he would be placed in the centre rank between two of his comrades, who would steer him by his elbows in the required direction. No-one was allowed to fall out, or be left behind. . . . As the columns approached a bridge, there would be a flurry of activity by the sappers waiting there. The engineers would then detonate the charges under the bridge, giving little time for the last Grenadier to find cover from the hail of bricks and debris which followed the explosion. The roads were littered with broken down and damaged vehicles, some were burnt out, and others . . . had simply run out of petrol. Refugees were everywhere . . . old people and invalids were just left sitting or lying in the shade of the trees, thoroughly exhausted, and unable to go any further. . . . We marched through all this desolation and despair, unable to help.

J. E. Bowman, then a Lance-Bombardier in the 22nd Field Regiment Royal Artillery, describes what it was like on May 28 as he too, with his beloved gun,¶ retreated without any idea of where he was going:

Obviously the whole front was becoming compressed and the roads more and more congested. . . . There was this village in which we hesitated and halted, running into the Hun, under shell fire and pointing the wrong way. Our infantry were busily engaged kicking open doors, lobbing grenades through windows and protecting each other as they darted from cover to cover. . . . Through debris, past sagging walls and burning interiors we edged along. . . . Through a broken window I glimpsed a body hanging by the neck. Summary justice was meted out in these parts. We crept along, up a corridor with enemy troops very close on one side, and not very far on the other.

Private Gordon Spring of the 2nd/5th Royal Leicestershire Regiment described a typical moment of the retreat.

We got to this barn and dead tired fell asleep in the hayloft. When I woke up there were Germans below us. We had to wait for dark, jump and leg it. We came across another building. I did have a Thompson [sub]machine gun with me. We approached it warily. Nothing there. We’d just turned around to leave and shots rang out. My sergeant was dead. In anger I rushed back blasting away with [it]. I shot three of the bastards, but then needed to get away myself. No shots followed me.

On Tuesday, May 28, the entire BEF, as well as several French divisions, was converging painfully on Dunkirk from three directions, constantly machine-gunned and bombed from the sky, a sweltering mass of over 400,000 men, some in vehicles of every description, most on foot, many of them in fierce close combat with the enemy, with the “sappers” (Royal Engineers) blowing up bridge after bridge over rivers and canals, often just as the Germans reached them.

Ahead of them was the glow and black smoke cloud of Dunkirk—they only had to get there.

Although there was no way the soldiers could know it, the British War Cabinet was still dealing with the politely expressed doubts of Lord Halifax about the wisdom of continuing the war. That afternoon the prime minister made a dignified statement to the House that “the Belgian Army [had] ceased to resist the enemy’s will” and surrendered. He had been dissuaded at the last minute from heaping scorn on the king of the Belgians, and went on to speak perhaps his finest words on the war: “Meanwhile, the House should prepare itself for hard and heavy tidings. I have only to add that nothing which may happen in this battle can in any way relieve us of our duty to defend the world cause to which we have vowed ourselves; nor should it destroy our confidence in our power to make our way, as on former occasions in our history, through disaster and through grief to the ultimate defeat of our enemies.”

Churchill had not yet acquired the affection of his own party—there were still louder cheers for Chamberlain than for the new prime minister. Their hearts were still with Chamberlain, not him. Applause had been surprisingly tepid and perfunctory in the House when he spoke of “blood, toil, tears and sweat.”

On the other hand, Churchill had, as if by instinct, found the right phrases to appeal to the public. They were prepared to suffer through “disaster” and “grief” so long as their government was willing to fight, and Churchill’s natural bellicosity caught the national mood, even if it did not appeal to many of his own party.

The division between the old and the new showed up when the War Cabinet met on May 28. Halifax had Sir Robert Vansittart, perhaps the most determined anti-appeaser in the Foreign Office, find out exactly what the Italian government had in mind. This was an odd choice for the task since Vansittart was vehemently opposed to the dictators, and to Halifax’s patient search for peace as well, and the choice may have been intended to put Vansittart in his place. In any case, he brought back from the Italian Embassy the message that what Mussolini expected was a “clear indication” that Great Britain wanted his mediation. The prime minister instantly pounced on this. “The French,” he said, “were trying to get us on to the slippery slope.” There was some rather testy discussion about the French approach to Mussolini, and about Reynaud’s hopes for an Allied appeal to President Roosevelt. Arthur Greenwood, the (Labour) minister without portfolio, echoing Churchill, dismissed the latter suggestion bluntly: “M. Reynaud was too much inclined to hawk round appeals. This was another attempt to run out.”

As recorded in the minutes, Halifax eventually staked out his position clearly: “He still did not see what there was in the French suggestion of trying out the possibilities of mediation which the Prime Minister felt was so wrong.”

Churchill staked out his ground: “The nations which went down fighting rose again, but those which surrendered tamely were finished.”

It is possible that Halifax would have carried this argument to the point of resigning, thus causing a cabinet crisis, but fortunately Churchill was obliged to end the War Cabinet to attend a meeting of the full cabinet, which had been arranged most providentially “earlier in the day.”

There he made a much more impassioned impromptu speech of nearly one thousand words, telling the cabinet very frankly of the disastrous military events of the past few days, and ending with the conclusion that he had not so far been willing to present to Lord Halifax.

It was idle to think that if we tried to make peace now, we should get better terms from Germany than if we went on and fought it out. The Germans would demand our fleet—that would be called “disarmament”—our naval bases, and much else. We should become a slave state, though a British government which would be Hitler’s puppet would be set up—“under Mosley# or some such person.” And where should we be at the end of all that? On the other side, we had immense reserves and advantages. Therefore, he said, “We shall go on and we shall fight it out, here or elsewhere, and if at last the long story is to end, it were better it should end, not through surrender, but only when we are rolling senseless on the ground.”

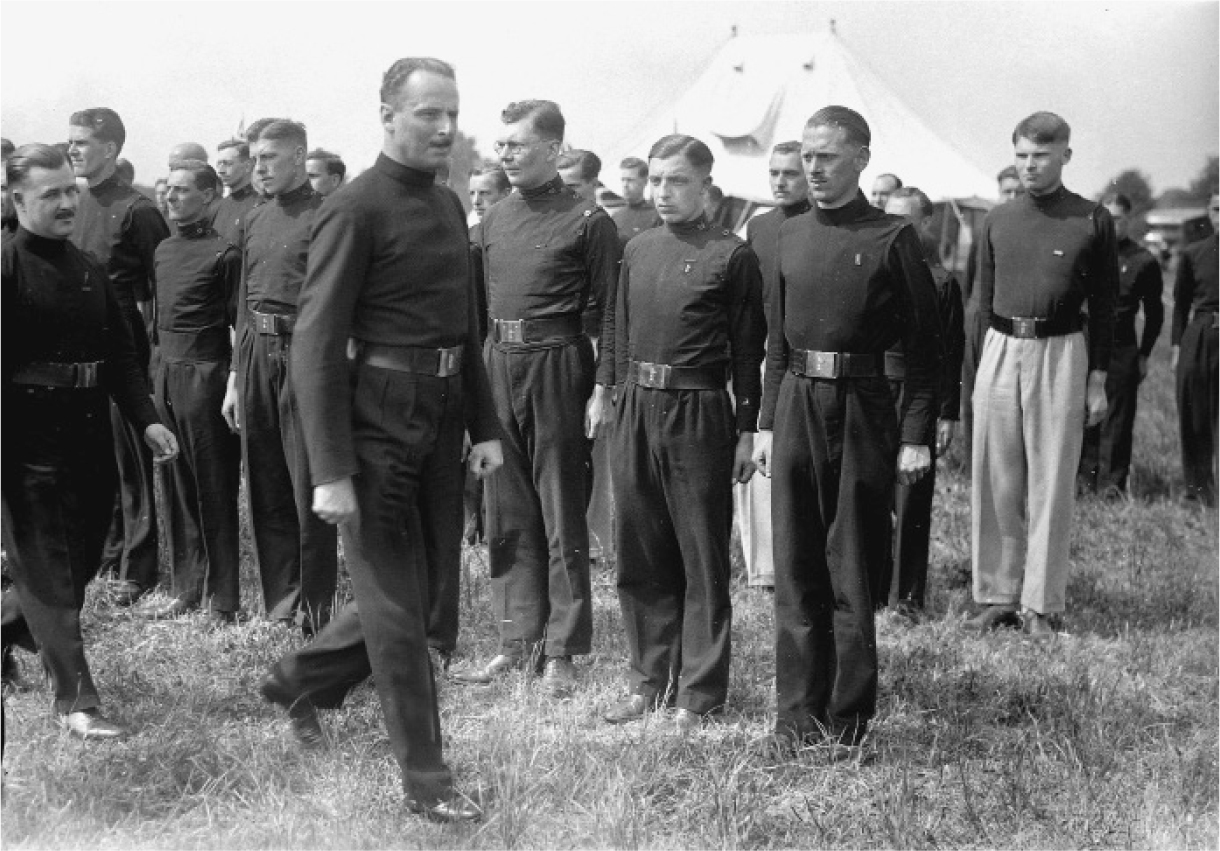

Sir Oswald Mosley, Bt.

These were the words he had been unwilling to address directly to Halifax, and they produced first a murmur of assent, and then a rare explosion of passion seldom experienced in British politics among the twenty-five members of all three major parties in the cabinet—the members of the War Cabinet did not attend the meeting, rather a pity, although it was just the kind of theatricality that Halifax deplored, noting, “It does drive me to despair when [Winston] works himself up into a passion of emotion when he ought to make his brain think and reason.” But Churchill was as moved by his own words as his audience was, the mark of a born orator. “Quite a number seemed to jump up and come running to my chair, shouting and patting me on the back,” Churchill recalled later, a feeling that he thought was almost universal, “a white glow,” as he described it fulsomely, “overpowering, sublime . . . ran through our Island from end to end.”

The “white glow” did not extend to Halifax when the War Cabinet resumed about the time that I was saying my prayers, but it had stiffened Churchill’s resolve in the meantime. The cabinet had spontaneously and emphatically backed his position against Halifax’s search for peace terms. Halifax was no coward—he had sought active service in the First World War despite having been born without a left hand, a defect he nearly always managed to hide, and he would have been as willing as Churchill to die choking on his own blood if needs be, but he did not think that a fight to the finish was necessary if Hitler’s peace terms were to prove acceptable. There was not much chance they would be, of course—he knew that; after all he had met Hitler—but he thought it was prudent and logical to find out before Britain was bombed or invaded.

But Churchill’s determination to fight on was reinforced now by the knowledge that he had the backing of the full cabinet—not only that, their applause and admiration—and he ended the argument between himself and Halifax abruptly about the time that I fell asleep in Hampstead. He would not join the French in making an appeal to Mussolini, or allow Halifax to continue his exploration of that possibility. When Halifax brought up once again Reynaud’s proposal for an Allied appeal to President Roosevelt, the prime minister put an end to that too. He thought that “an appeal to the United States would be altogether premature. If we made a bold stand against Germany, that would command their admiration and respect; but a groveling appeal, if made now, would have the worst possible effect.”

Late that night, the prime minister called Premier Reynaud in Paris to give him the news personally, and exhorted him to remember that “we may yet save ourselves from the fate of Denmark or Poland.” It was in vain. Reynaud was looking toward the Somme and the Seine, where French resistance was crumbling, Churchill toward the beaches of Dunkirk, where the BEF was beginning to mass.

That day, May 28, Admiral Ramsay’s ships took 5,390 men off the beaches to the east of Dunkirk, and 11,874 from Dunkirk harbor. Even Captain Tennant, the senior naval officer in Dunkirk, thought that the evacuation could not be continued for more than another thirty-six hours, and that the chances were “100 to 1 against being able to bring a large proportion of the troops back.” Nobody, least of all the Germans, could have guessed the evacuation would go on for another full week, or that 338,226 troops would be brought home.

_________________________

* Like Lincoln, Churchill had a gift for uplifting oratory about grim news, perhaps borne out of his long relationship in war and peace with David Lloyd George. His first speech as prime minister struck exactly the right note: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.” He had an instinctive understanding of the fact that the British as a people dislike boasting, and pride themselves not on victory but on being able to “take it.” The Ministry of Information and the press were slow to catch up with him.

† Whipped cream, without a frothy dollop of which no cup of coffee or dessert in Austria or Hungary is complete. It was a word often used in Hollywood in the days when many directors were Central European, meaning more sentiment or glamor, as in “Do it again, but this time with more Schlag.”

‡ SIS stands for Secret Intelligence Service, or MI6, and SOE for Special Operations Executive, intended to sow terror and subversion in German-occupied Europe.

§ An alternative question was “What sports do you play?” to which the right answer was rugby and cricket. My father would have found this one equally difficult, since he played neither.

¶ A “gun” always means an artillery piece, in this case “a 25-pounder Mark Two” (the standard field artillery piece of the British Army in World War Two and the Korean War), never a pistol, rifle, or machine gun.

# Sir Oswald Mosley, Bt., was leader of the British Union of Fascists, and was imprisoned during much of the war together with his wife, Diana, one of the Mitford sisters. The Führer had been a witness at their marriage in the Berlin home of Reich Propaganda Minister Dr. Joseph Goebbels.