The beach at Dunkirk.

The beach at Dunkirk.

IRONICALLY, BY May 28 the German generals were becoming aware that they had made a major mistake. Admittedly much of this would come out in the form of being wise after the event, expressed to Allied interrogators after they had surrendered, during which almost to a man they cast the entire blame on Hitler.

The argument that the area around Dunkirk was not “good panzer country” was true enough, but had the Germans nevertheless committed the three armored divisions close to it on May 26 or 27, it is hard to imagine they would not have broken through the perimeter defense of Dunkirk and exposed the beach and the shore to direct fire. As a result a reasonably successful evacuation might have been turned into a bloodbath. As would so often be the case later in the war, Göring had promised more than he could deliver: the decision to rely on the Luftwaffe to finish off the BEF was a mistake—the combination of bad weather and thick black smoke over Dunkirk greatly diminished the accuracy of the air attacks, and the sand dunes of the beaches tended to absorb bomb explosions rather than to produce lethal bomb splinters.

Even General Halder, usually an acerbic commentator on military decisions other than his own, merely remarks to his diary with a certain degree of schadenfreude that “the British are streaming back to the coast and trying to get across the sea in anything that floats. La Débâcle.”*

In this case, however, Halder was wrong. The evacuation of the BEF at Dunkirk was not a downfall; it would prove a salvation. Had the Germans been in a position to slaughter the BEF or compel its surrender, the polite disagreement between Halifax and Churchill in the War Cabinet might have taken a very different turn, but the arrival of “anything that floats” was about to change disaster into a victory of sorts—and to demonstrate, as so often in British history, the advantages of being a seafaring nation and of living on an island.

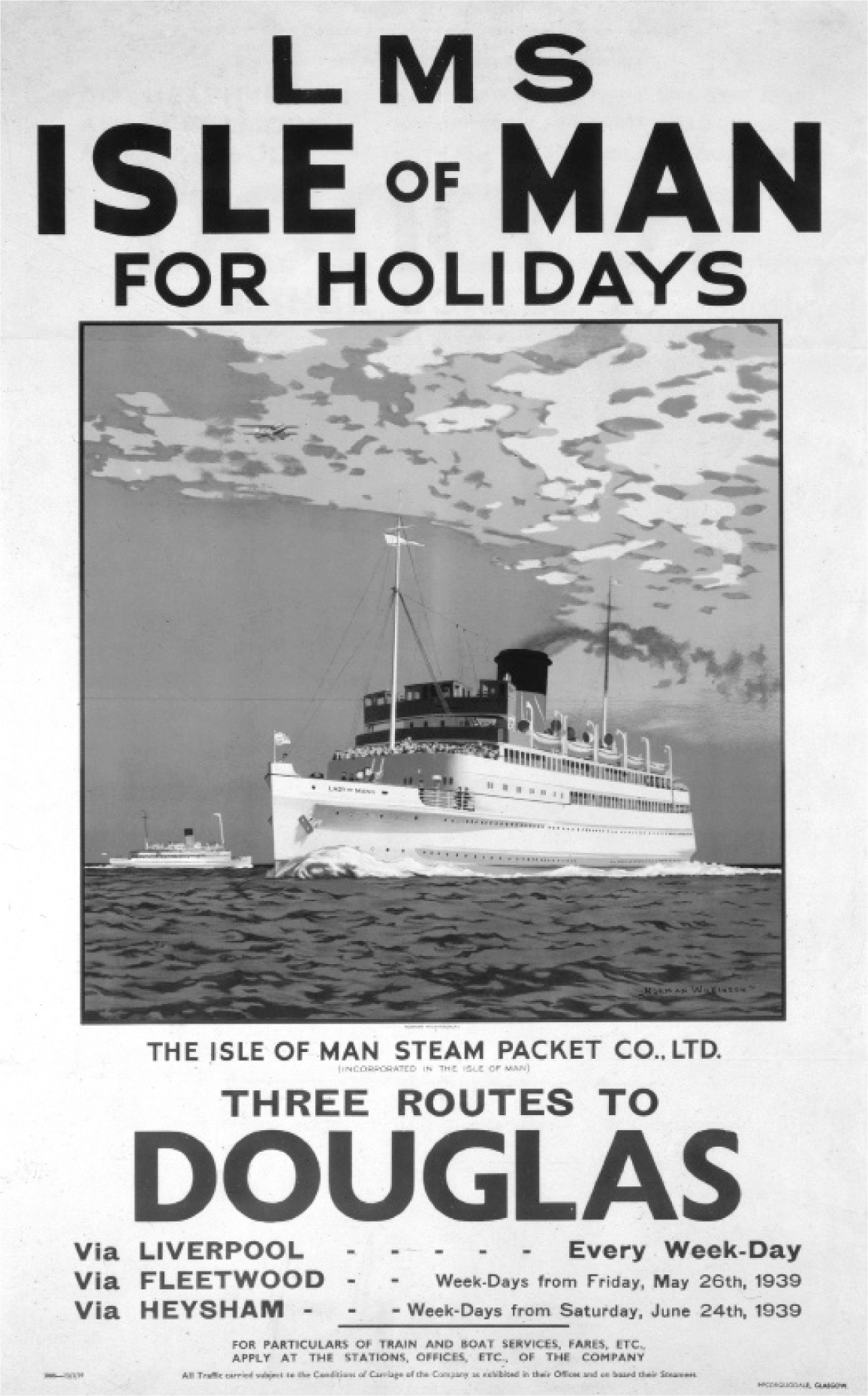

The initial days of Operation Dynamo were not an unqualified success. Mona’s Isle, a former pleasure steamer of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company, managed to berth in Dunkirk’s battered inner harbor and take off 1,420 troops, but was shelled on her way home, one shell disabling her rudder, then was “machine-gunned from the air” by German fighter aircraft, which killed 23 men and wounded 60. That and the heavy bombing of the town and inner harbor led Captain Tennant to advise Dover that shipping should concentrate on the beaches to the east of Dunkirk and the outer (or eastern) mole. Use of the beaches would require a multitude of small boats to carry troops out to ships waiting in deeper water, while the outer mole had never been intended for ships to tie up to—it was essentially a narrow breakwater, a long stone jetty the last few hundred yards of which consisted of a fragile wooden extension. A kind of ramshackle boardwalk had been built for most of its length, just wide enough for four or five people to walk abreast, but in places it was missing whole sections. The eastern mole was a good place to fish from, but not necessarily one from which to evacuate more than 100,000 men under fire.

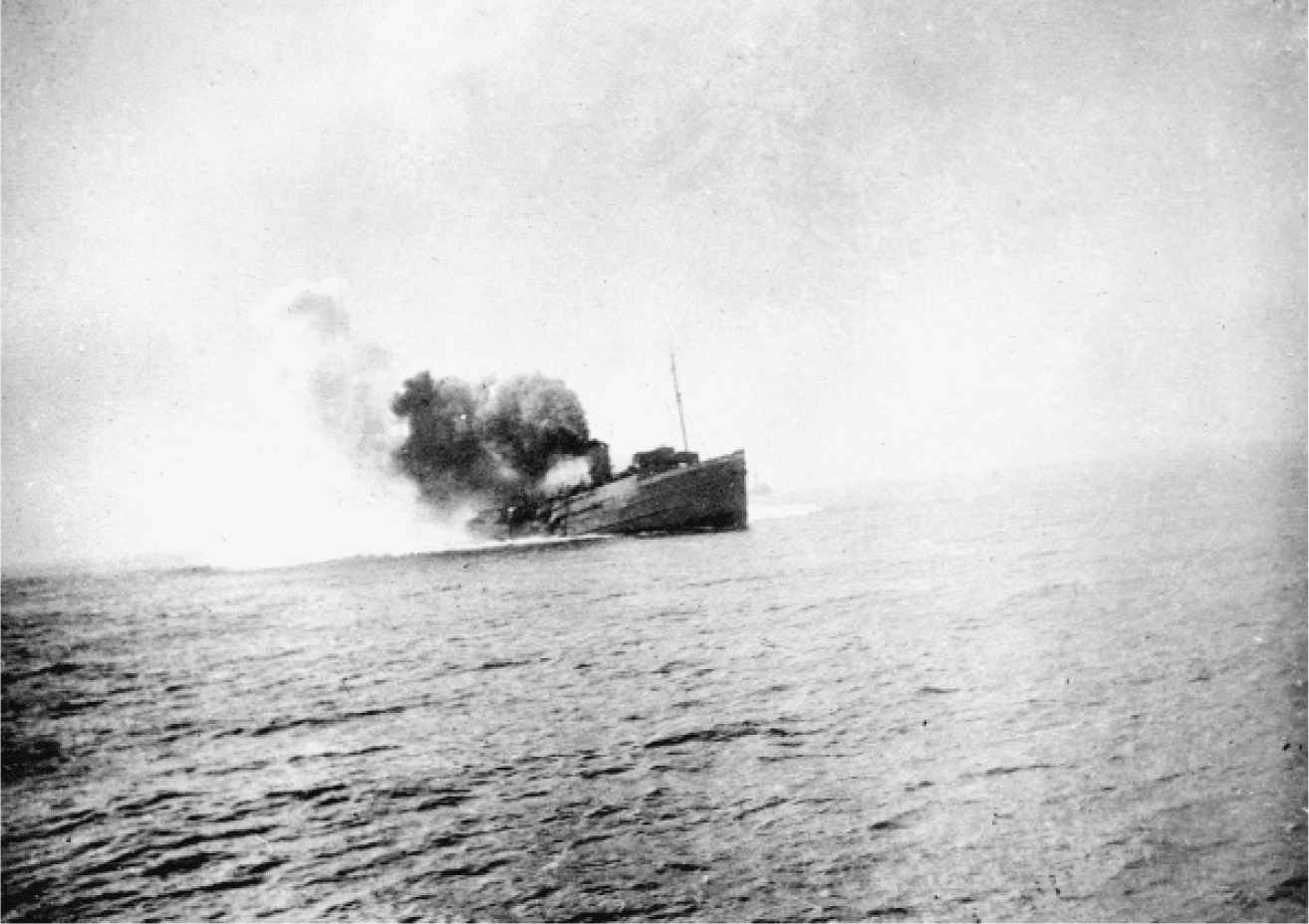

The Isle of Man steamer S.S. Mona’s Queen goes down after hitting a mine at Dunkirk, and opposite, in her peacetime role.

It was Tennant’s genius to see that it could be done, and to start the movement of men down the beach to the east of the harbor from Nieuport Bains toward the eastern mole, along a stretch of dunes sparsely covered with grass almost twenty miles in length on May 28. At first, his concern was to take off “line of communications troops” (the “useless mouths”) and the wounded, but as units of the fighting troops began to converge on the beach, Lord Gort, who placed his headquarters that night at La Panne, a modest beach resort about ten miles east of Dunkirk harbor, soon realized that getting the fighting units back to Britain was a more urgent priority than sending the wounded and line of communications troops home. It was a harsh, but sensible, military decision. Although not put into practice universally or with any kind of draconic precision on the beaches, it was more easily enforced as troops lined up neatly to file onto the eastern mole. If there is one thing the British are good at it is queuing, as the troops were to prove (with some exceptions) over the next few days.

The beach at La Panne.

By May 28 the BEF and at least three divisions of French troops had been driven back to what was called “the canal line,” forming a purse-shaped pocket that followed the Canal de Bergues from Dunkirk east to Furnes, then the Canal de Furnes northeast to the sea at Nieuport Bains. At its widest point the pocket was only six miles deep. The ground to the west of Dunkirk was held by one loosely spread French division, and from there the German front line was less than five miles from the center of Dunkirk—all evacuations would therefore have to take place from the Dunkirk eastern mole and from the beaches to the east of the port. Because the focus of attention since the war has always been on the “little ships” and the beaches, the hard, unrelenting fighting of those British and French troops who were holding the perimeter, without whose sacrifice no evacuation could have taken place at all, is seldom given its due. The relatively slow pace at which the Germans were able to compress the perimeter is an indication of just how hard the fighting was. Even deprived of the panzer divisions that would have dealt the BEF the coup de grâce, the Germans had an immense superiority in numbers and equipment, and no inclination to slacken off now that they were in sight of their goal.

Each of the many bridges across the canals was the scene of fierce fighting. A British war correspondent in Nieuport describes how one “gallant sapper,” discovering that the fuse to the charges laid by the Belgians to destroy a bridge had been placed on the wrong side of the bank, ran back across it under fire, lit the fuse, then swam back across the canal as the bridge exploded.† The Germans themselves were astonished at the ferocity and skill of the British defense, although in many places British troops were beginning to run short of small arms ammunition—in some units soldiers were issued only five rounds—a case of the organization collapsing, since the area surrounding Dunkirk was full of abandoned trucks, many of them loaded with ammunition. Clearly, if the Germans could break through the relatively thin line holding the eastern flank of the perimeter, they would be able to roll up the scattered and poorly armed mass of British forces on the beach waiting for evacuation, but at no point did they ever manage to break that thin line. They forced it back relentlessly for five days, but it continued to hold to the very end, when the perimeter consisted of nothing more than the eastern mole, a few streets, and a few miles of open beach—a remarkable feat of arms. A thoughtful German Army report issued on the battle, Der englische Soldat, reflects a certain admiration for the British soldier, particularly when it came to defense: “He bears his own wounds with stoical calm. He did not complain of hardships. In battle he was tough and dogged . . . a fighter of high value. . . . In defense the Englishman took any punishment that came his way” (italics in the original).

The Germans set a high store on careful infiltration by small groups and sniping, intended to break the enemy’s will, and they were good at both, which probably explains why so many of the British troops believed they were being shot at from behind or from the flanks by renegade “fifth column” civilians, and also the high number of civilians shot out of hand for looking suspicious, or for replying in Flemish (often mistaken for German), or simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

One artillery battery was so harassed by sniping that a gunner took to the lower branches of a tree to reply with a Boys antitank gun, a heavy weapon of amazing awkwardness that looked like a complicated piece of plumbing and was normally carried by two men. “Mouthing a string of indecipherable Gaelic curses, with the word ‘bastard’ frequently interpolated . . . at his one and only shot, L—— was propelled from the tree by the powerful recoil and was brought to the ground, shaken but with no limbs broken.”

What sustained the troops on the perimeter, which the German report fails to mention, was above all a sense of humor and ironclad, old-fashioned loyalty to their own regiment or branch of service: among them the Black Watch, the South Lancashire Regiment, the Royal Irish Fusiliers, the East Surrey Regiment, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, the Coldstream Guards, and the Grenadier Guards; these and others were among the finest and oldest regiments of the regular British Army, not to speak of the batteries of the Royal Artillery, which kept up a steady shelling of the enemy despite heavy losses until they ran out of ammunition or were ordered to blow up their own guns. Many of the infantry regiments still retained fierce local loyalty, for example, the 2nd/5th (Territorial) Battalion of the Leicestershire Regiment. The regiment, whose nickname was “the Tigers” because of the Indian tiger on their cap badge and buttons, dated back to 1688 and was recruited almost entirely from the city of Leicester—soldiers and noncommissioned officers knew each other and had roots in the city or its suburbs, creating bonds that were unlikely to break even in the most extreme circumstances. The officers came from the same area, were simply of a different class. The Black Watch too was a regiment with strong local roots, still recruited from the same area of the Scottish Highlands, and fiercely devoted to the regiment’s long history, customs, and traditions, including its famous black-and-green kilt, the pattern and color of which has been borrowed by manufacturers of shirts, dressing gowns, and Scottish souvenirs all over the world.

As the fighting troops pulled back under German pressure, all of them remarked on the squalor and chaos of the roads jammed with refugees, Belgian and French troops, many of whom had thrown away their weapons and abandoned vehicles of every description. One officer of the Royal Irish Fusiliers reported being overrun by a horsed regiment of French cavalry, which “pushed us with extreme selfishness into the ditch,” and commented disapprovingly on the “anachronistic appearance of this unit with its carbines and its sabres,” while to their other side British gunners “bore themselves in a pleasantly business-like way,” firing at the enemy in textbook fashion as if they were firing a salute at the king’s birthday.

The fairest assessment of May 28 is that those troops in contact with the enemy were holding out magnificently under increasingly difficult conditions, while those who had reached the beach between Nieuport and Dunkirk were suffering from lack of organization and control, caused in some cases by officers taking the first chance they could to get on a boat, leaving their men behind. Fighting troops, as they approached the evacuation area, were shocked. “The scene on the beaches was indescribable,” wrote Jack Pritchard of the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards. “Long columns of troops stretched far into the sea. . . . All kinds of debris littered the foreshore. Haversacks, rifle, bayonets, thousands of sealed tins of Players cigarettes, tinned foods and discarded clothing, stretched as far as the eyes could see. . . . Here and there lay a dead horse, some stinking to high heaven, with their feet in the air, and their distended stomachs seemingly ready to burst. Others were being mutilated by Frenchmen, who were cutting steaks from the hindquarters of the unfortunate animals.”

“In the roadside fields,” as the official history describes it, “burning equipment and abandoned stores heightened the appearance of disintegration. But through the formless texture of the scene the British divisions which had been fighting by day and retiring at night wove a firmer thread; marching doggedly, tired and often hungry, shocked by all the crowding and confusion but too preoccupied to bother much, they moved imperturbably through a crumbling world, upheld by discipline and the traditions of their Service.”

That Captain Tennant, in the highest traditions of his Service, managed to get nearly 18,000 men off the beaches and the eastern mole on May 28 was a kind of miracle. By that night the evacuation fleet had grown to “3 hospital carriers, 7 personnel steamers and 2 destroyers” operating from the eastern mole in Dunkirk Harbor, and a strange mixed fleet operating over more than twelve miles of open beach to the east of Dunkirk around Bray consisting of: “some twenty destroyers, 19 paddle and fleet [mine] sweepers, 17 drifters, 20 to 40 shoots, 5 coasters, 12 motor-boats, 2 tugs, and 28 pulling cutters (or row boats) and lifeboats.” The Dutch schuyts, like the coasters, motorboats, and tugs, could get closer in to the beach than the destroyers and minesweepers, but it was realized at once that the critical factor would be the oared “pulling cutters” and lifeboats that could actually approach the beach close enough to pick up men as they waded into the water to waist or shoulder level, then take them out to the larger ships waiting offshore—although if they ran aground it took a tremendous effort to slide them back into the water again, or they had to wait under bombing or machine-gunning for the rising tide to refloat them.

More small boats were desperately needed, as well as men experienced in handling them; in the meantime the boats from the destroyers were used, but there were constant problems as “they were rushed and swamped by the soldiers.” Order was eventually restored during the day, and by nightfall the boats from two of the destroyers had carried off nearly one thousand men “during continuous bombing attacks.” This was a hopeful sign, but Tennant was still not optimistic about the chances of evacuating more than a fraction of the BEF. The surf on the beaches complicated the task of getting men into the boats without capsizing them; as for the eastern mole, tying ships up to it in the daylight hours made them a sitting target for German dive-bombers.

The German Army seems, for once, to have been caught napping, or perhaps it was simply not prepared for the stout resistance of a foe they thought had already been defeated. The ubiquitous 12th Lancers, now reduced to five armored cars and “a fighting lorry,” was thrown again into the thick of the fighting around Nieuport to secure the eastern flank of the perimeter, where the canal line met the sea. Henry de La Falaise describes a bold attack on a German motorized detachment late on May 28, in what he calls with his usual light touch “a lively encounter,” during which many Germans were killed.

By the end of the day, he recalls, the 12th Lancers were “holding the bridge at Furnes,” with “intense machine-gunning and artillery fire all along the front. The gun fire is especially sharp and spectacular. . . .” After a “forlorn hope” defense of a bridge at Nieuport, during the course of which the 12th Lancers were relentlessly bombed and shelled, what remained of them would be withdrawn to a new position within six miles of Dunkirk, only eighteen days after they had crossed the Belgian frontier at dawn as the leading unit of the Allied attack.

_________________________

* Halder is presumably referring to Emile Zola’s novel about the French defeat of 1870.

† This sounds like a propaganda story, but in Charles More’s The Road to Dunkirk the sapper, Lance-Corporal Hourigan, is named and the incident described in detail.