EARLY IN THE morning of Friday, May 31, Churchill and his party left for Paris in two de Havilland Flamingos, escorted by nine Hurricanes. Popular with neither its crews nor its passengers, the Flamingo was slow, cramped, noisy, and prone to ground accidents, and in this case the journey was protracted by a long roundabout route over the Jersey Islands (soon to become the only part of the United Kingdom occupied by the Germans, for five long years), then due east to Villacoublay, a French Air Force field close to Versailles, in order to avoid enemy fighters. Churchill does not seem to have cared or noticed—action, risk, danger, movement always cheered him up and got his juices flowing. He was still, at heart, the same young man who had participated in the last major cavalry charge of the British Army in 1898 at Omdurman in the Sudan with the 21st Lancers, Mauser C-96 automatic pistol in hand (a present from his mother, Lady Randolph Churchill), shooting dervishes at a gallop as they appeared before him.

He paused for lunch at the elegant British Embassy in Paris (whatever the crisis, Churchill was not a man who ever skipped a meal, or hurried one, if he could avoid it), but once the meeting of “the Supreme Allied War Council” began, it quickly became apparent that the small number of French troops who had been evacuated so far from Dunkirk was not the chief concern of the French. They wanted more British troops, and above all more British fighter squadrons, neither of which the prime minister was in a position to provide. The truth is that the French War Cabinet had already written off the battle in the north, although nobody had as yet bothered to tell Admiral Abrial in Dunkirk of the fact. With the prescience of the damned they were waiting for the German armies to attack southwest, cutting off the Maginot Line and rendering it useless, and isolating Paris, which they correctly anticipated would fall like a ripe piece of fruit. The last days or hours of the “bridgehead” at Dunkirk was by now the least of their concerns. Even the news that Lord Gort would be ordered to leave that night, now that his command was reduced to the strength of a corps, did not make much of an impression on them, any more than did Churchill’s announcement that henceforth fighting troops would be brought off before the wounded, since the most urgent need was to reform and rearm those “who were vital for continuing the struggle.”

Churchill’s robust presence seems to have momentarily reanimated Premier Reynaud, but did not win over most of those present, possibly because he insisted on speaking in execrable French throughout the meeting. When Admiral Darlan, the commander in chief of the French Navy, proposed sending a message to Admiral Abrial in Dunkirk that when the troops holding the perimeter were obliged to withdraw, British troops should be embarked first, the prime minister intervened, and with a vivid gesture locked his arms together in front of his chest. “Non, bras dessus, bras dessous” (arm in arm), he said vehemently, and promised that the French would be gotten off first from now on.

The presence of Marshal Pétain, now deputy premier, put a damper on the proceedings. Major-General Hastings Ismay, Churchill’s chief staff officer and military adviser, trenchantly described the atmosphere of the meeting: “As we were standing around the table . . . a dejected-looking old man in plain clothes shuffled towards me, stretched out his hand and said, ‘Pétain.’ It was hard to believe that this was the great Marshal of France whose name was associated with the epic of Verdun. . . . He now looked senile, uninspiring and defeatist.” Captain Berkeley, a member of the War Cabinet military staff and a fluent French speaker (whose gift does not seem to have been required), remarked that Pétain “looks his 84 years.” Berkeley also remarked that Churchill’s favorite, Major-General Spears, was “muscling in on a very high plain,” causing tremendous indignation among the French. (Berkeley may have been among those who thought that Spears’s ability as a French linguist was less than his reputation among his fellow British.) “An agreeable person but, it seems, a ruffian,” Berkeley commented. “I hear sad accounts of Desmond Morton, Prof. Lindemann and Brendan Bracken* also. PM does like glib imposters!”

At the conclusion of the long meeting—it appeared even to Churchill, who was not always sensitive to the feelings of others, that Pétain’s attitude throughout “was detached and sombre”—Spears challenged the old man face-to-face about what would happen if France sought a separate peace. “I suppose you understand, M. le Maréchal, that that would mean blockade?” Pétain did not reply, his icy blue eyes reflecting nothing, least of all his feelings about a British temporary major-general addressing a marshal of France this way, but someone else among the French smoothly remarked that in the event that “a modification of foreign policy,” a wonderfully tactful French phrase, was forced upon France, a British blockade of French ports “would perhaps be inevitable.” Spears then spoke directly to Pétain, pointing out sharply that it would mean not only blockade “but bombardment of all French ports in German hands.”

The unthinkable had been spoken. Pétain said nothing—it was as if he had not heard Spears speak to him—but after the departure of the British he turned to Reynaud and said, “And now your ally threatens us!” The British were now Reynaud’s ally, not France’s, and the full meaning of it was unmistakable—that Reynaud could no longer rely on his own cabinet.

Despite all this, Churchill’s spirits were buoyed. He insisted on “tramping through the tall grass in the flurry of propellers with his cigar like a pennant,” to review the nine Hurricanes of his fighter escort. He had reason to be pleased, for the number of troops being returned was rising sharply—over 68,000 would be brought home by the end of the day on May 31, bringing the total so far to 194,620. More than half the BEF was home.

For those on the beach at Dunkirk, however, it did not seem like a triumph. By now Dunkirk Harbor was almost blocked by the wrecks of ships the Germans had sunk, there were great gaps in the eastern mole, and the foreshore of the beach was littered with wreckage and sunken boats and ships. By noon on May 31 the destroyers that had been waiting offshore along the beach had to withdraw farther out to sea as they came under fire from German heavy artillery, 155 mm and heavier. “Each time the destroyers put to sea, gloom settles along the beaches, everyone wears a long face,” wrote Henry de La Falaise. Remarkably, the 12th Lancers had not only been kept together but retained their weapons and their kit. After nine hours in the dunes and on the beach under heavy bombing and artillery fire, the colonel arrived in a small car salvaged from the beach, and the regiment was ordered to follow him toward Dunkirk, almost ten miles away. La Falaise’s squadron was placed in arrow formation. “The Major walks along unflinchingly. He is shouldering parts of the kits of many exhausted men and has not once slackened his pace or ducked to dodge bombs and bullets.” The thick sand slowed the men down, and it was early evening before they reached the outskirts of Malo-les-Bains, after seven miles of marching under fire. “When we reach [the colonel] he tells us that we have now come to the end of the road and must take to water. We are going to embark!”

Longboats and launches were coming toward them, and the sailors signaled the troopers to come out as far as they could into the water. “The wind is rising and there is quite a swell as everyone wades out into the cold sea. We are soon shoulder deep.” Together with the senior officers of the regiment, La Falaise helped to get the men into the launches without capsizing them, then tried to make it to a nearby dredger that was coming inshore. “A heavy swell which washes over my head makes me lose the haversack I was holding above the water. In this I had put a dry shirt, a sweater, some valued personal belongings and my gas mask. I try in vain to recover it, but it sinks to the bottom like a stone, waterlogged.” A launch floated near him, but he did not have the strength to climb into it, weighed down by his heavy soaked uniform, his riding boots, and his steel helmet. He dropped his helmet and his revolver into the sea and tried again, at the end of his strength now, then “four strong arms” hauled him into the launch. “All I can hear is the roaring of the German motors sweeping over us, the screaming of the bombs and the loud explosions.” Another French officer helped him extract a treasured flask of brandy from his pocket, and they shared it as the bombs fell all around them.

Two hours later La Falaise was “sitting stark naked on a heap of coal in the engine room of the dredger,” with his uniform hung in front of the furnace to dry, still shaking from the cold, while the damaged dredger drifted since, as a stoker told him cheerfully, she was off course and lost in a minefield. A passing minesweeper hailed the dredger and gave her master a new course, and La Falaise, with what remained of his adoptive regiment, proceeded toward Dover and the White Cliffs at a stately two knots, since the German bombs had loosened some of the bow plates. Wearing his dried uniform, another man’s dirty boots in his face, La Falaise fell fast asleep in the crowded wheelhouse for the first time in days, the war behind him for the moment.

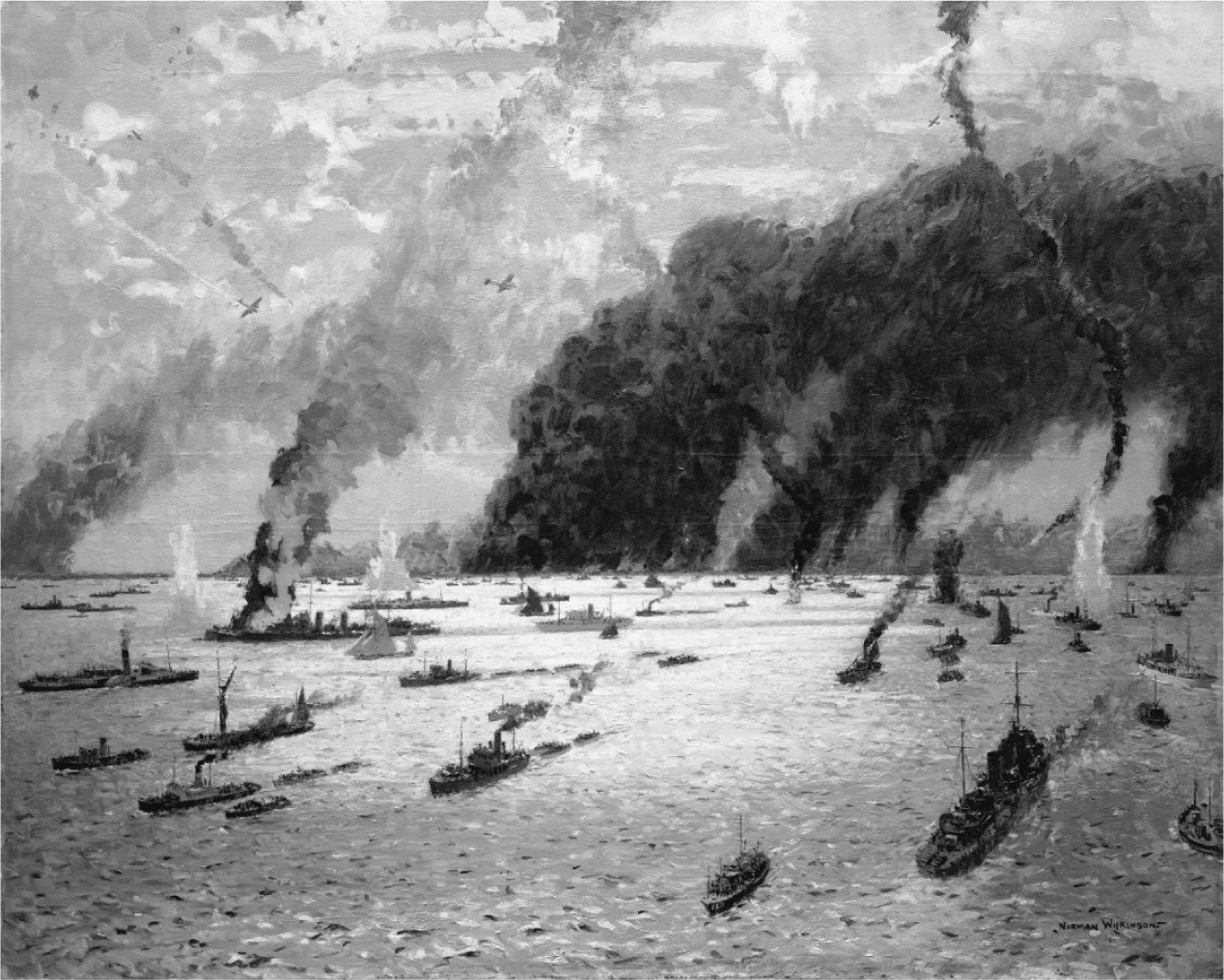

The beach presented an extraordinary spectacle from the sea. “Almost the whole ten miles of beach was black from sand dunes to waterline with tens of thousands of men. In places they stood up to their knees and waists in water. . . . It seemed impossible we should ever get more than a fraction of all these men away. . . .” The great need was “pulling” boats. (In the Royal Navy oarsmen “pull”; only in civilian boats do they “row.”) The day before had seen the arrival in numbers of the vast and strangely assorted fleet of small boats that was required to get men off the beach and farther offshore where the larger ships waited (it was also the day when the Channel Islands passenger ship Dinard, converted into a hospital ship, made it out of Dunkirk harbor under shellfire, earning for her peacetime stewardess, the fifty-nine-year-old Mrs. A. Goodrich, the only Mention in Dispatches awarded to a woman during the evacuation).

May 31 also presented the rescuers and the rescued with a new and serious problem: bad weather, “a fresh northerly breeze blowing and at once a heavy sea.” Of course the word “breeze” connotes something different for a sailor than for a landsman, still more a “fresh” breeze. It produced mountainous surf, which broached and capsized many small boats and forced others onto the beach, where they had to be abandoned as the tide fell—both soldiers and “pullers” were by now too exhausted to drag them a hundred yards or more to where water was deep enough to float them as the tide ran out. By now a whole armada of “little ships” was at work, including the lifeboats of every port in southern England, the “floating fire-engine” of the London Fire Brigade Massey Shaw, a fleet of Thames sailing barges (many of which were lost, and one of which, Lady Rosebery, carried the youngest seaman to be killed at Dunkirk, J. E. Atkins, aged fifteen), “old cutter-rigged cockle boats of the Thames Estuary,” the War Department’s launches, and five Royal Air Force motorboats (fast seaplane tenders of the kind T. E. Lawrence had served on in his last years in the RAF as Aircraftman Shaw), two of which were sunk. The names of the motor yachts, most of them captained by their owner, with the help of a civilian crew (including several teenagers and at least one woman), evoke a whole different peacetime world of summer day cruising on the rivers of southern England: Golden Spray, Gipsy King, Rose Marie, Count Dracula (a former World War One German navy launch), Blue Bird, Folkestone Belle, Gertrude, Grace Darling IV, Madame Sans Gêne (!), Miss Modesty, Our Maggie, Pudge, numerous Skylarks, White Lady, and Yola, to name only a few. Gaily painted and varnished, with gleaming brass, they were bombed and machine-gunned like every other vessel, and the Admiralty’s list of civilian vessels at Dunkirk is full of private motorboats bluntly described as “lost,” by my count sixty-nine, one of them only eighteen feet long, two of them rowboats, one of them described with blunt naval stoicism as “Mined & sunk with all hands.” This amounts to a loss of about 10 percent of the total number of privately owned ships and boats.

Nurses returning to Dover.

There had never been such a brave and bizarre fleet as that collected from the motor yacht owners of England, who included numerous doctors, a typographical designer, a scenery designer, and a pub keeper (the Gloucester Arms at Kingston). Several were owned by celebrities, like Blue Bird of Chelsea, the fifty-two-foot motor yacht built for Sir Malcolm Campbell, the famous world speed record holder (his land speed record was over 300 mph, set in 1935, and his water speed record was 141.740 mph, set in 1939). The oldest skipper was over seventy, many of the seamen were mere boys, and the actor Laurence Olivier’s brother, Gerard, not only sailed to Dunkirk but won a Distinguished Service Medal there. By May 31 the number of boats operating off the beach was so great that one skipper compared it to Piccadilly Circus at rush hour. The navy helped with charts, good advice, supplies of gasoline, water, and food and arranged for most of the hundreds of motorboats to be towed across the Channel and through the minefields, but the civilians were often treated with gruff no-nonsense commands by the professionals—one bewildered motor yacht owner entering Dunkirk harbor asked where to go (the harbor was strictly reserved for bigger ships) and was crisply told from the bridge of a destroyer, “Get out of the bloody harbor!”

On Friday May 31 the stream of yachts, fishing vessels, and small boats being towed by tugs and drifters made a continuous stream over five miles long, one that the Germans bombed and machine-gunned from the air all the way across. “The bombs dropped out of a cloudless sky,” one yachtsman recalled. “Some came down in steep dives. . . . One came low, machine-gunning a tug and its towed lifeboats. Then came another. We knew it was coming our way. It was crazy to sit there, goggle-eyed and helpless, just waiting for it, but there seemed singularly little else to do. The seconds were hours. ‘Wait for it and duck!’ shouted someone above the roar of the engines. ‘Now! and bale like bloody hell if he hits the boat.’ We ducked. The rat-a-tat of the bullets sprayed around the stern boats of our little fleet. . . .”

The number of people brought off the beach by the small boats and yachts was extraordinary. Dr. Basil Smith’s yacht Constant Nymph, for example, brought off over nine hundred men, an amazing feat for a twenty-foot motor yacht. Dr. Smith skippered his boat himself, with a crew of two Royal Navy stokers-in-training. It took him three days to get to Dunkirk, because of endless naval formalities, but once there he and his crew worked the beach for nearly twenty-four hours nonstop, with nothing to eat or drink, in constant danger of being hit by a bomb or swamped. Dr. Smith and his crew were ordered to hand his boat over to a naval petty officer and some naval ratings, but the petty officer soon got into trouble with Constant Nymph, the wind and waves having increased, and Smith and his two stokers had to give up their “tea and bread and butter and jam” on board HMS Laudania (a Dutch freighter taken over and armed by the Royal Navy) to take her over again. By the end of the day Constant Nymph’s engine was giving out—a constant problem with motor yachts was that people tended to put them up for the winter and not get around to servicing the engine until the summer, which in England means July and August—so Dr. Smith was obliged to turn his beloved Constant Nymph over to a naval drifter that was said to have mechanics on board, and return to England on the Laudania. Dr. Smith, who would be awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his services at Dunkirk, was a jaunty and self-confident man. As he boarded the Laudania and got his pipe going to his liking, an old soldier wearing the 1914–1918 ribbon saw him and remarked that he had thought this was “a young man’s war.” “Well, you’re no bloody chicken!” Smith replied, somewhat ruffled, but when he saw his face in a mirror with several days’ growth of beard, he thought he looked like a tramp. On the way home, he watched as the crew attempted unsuccessfully to blow up a drifting mine, and after she moored at Margate, the navy sent him home to Ramsgate in a taxi. Since Constant Nymph does not appear on any of the Admiralty lists of vessels lost at Dunkirk, he may have been eventually reunited with his yacht.

The vessels that did such heroic service on May 31—and the days before and after—were all sailed with reckless courage by soldiers and civilians alike. They included such oddities as “Falcon II, a sailing clipper of 1898, which had spent its working life bringing Port from Portugal to England,” surely one of the oldest boats at Dunkirk, a sailing barge named Ethel Maud built in 1889, and Chalmondsleigh, the motor yacht of the famed comedian and showman Tommy Trinder,† a favorite of the Royal Family. The Germans bombed everything that floated mercilessly, but fortunately few targets are harder to hit from the air than a moving vessel, and their bombing of Dunkirk itself was hampered by the dense clouds of black smoke from the burning oil tanks.

On shore in Dunkirk a tense binational drama took place on May 31, when Major-General the Hon. H. R. L. G. Alexander, on whom command of the BEF had descended with the departure of Lord Gort, paid a visit to Admiral Abrial in his bastion. Either because he had not been informed that the remaining British divisions were to be evacuated rather than participating in a last-ditch defense of Dunkirk, or because he knew but was determined to make General Alexander squirm, Abrial insisted that General Lord Gort had promised him three British divisions to defend Dunkirk. Abrial could hardly have chosen a better target for his sarcasm than General Alexander, the future field marshal and 1st Earl of Tunis, an Englishman who presented the perfect image of an English gentleman as perceived by the French, better even than that famous hero of Pierre Daninos’s bestselling book Les Carnets du major Thompson, who would typify to a later generation of French everything they ridiculed (and secretly admired) about the English. Like Churchill, Alexander was educated at Harrow, but unlike Churchill, who had been miserable there and did not become sentimental about Harrow until old age, Alexander as schoolboy had been something of a legendary cricket hero in what has been described as “the greatest cricket match of all time,” played between Harrow and Eton in 1910. Having chosen soldiering as a career rather than art, his first choice, Alexander went on to Sandhurst, was commissioned in the Irish Guards, and became a much decorated hero of World War One, winning the DSO, the MC, and the Légion d’Honneur, as well as the admiration of Rudyard Kipling, whose only son had been killed as an officer in the Irish Guards. Alexander was tall, handsome, wore a carefully trimmed military mustache, was always perfectly dressed and groomed whatever the conditions—the very picture of what a guards officer should look like. Unlike his colleague Major-General Montgomery (the future field marshal the Viscount Montgomery of Alamein), Alexander was also modest, well-mannered to a fault, and horrified of being thought brainy or pushy. It would have been hard to find an officer in the British Army less suited than General Alexander to breaking to the prickly admiral the news (if it was news, about which there is much doubt) that the BEF was going, rather than staying on to defend Dunkirk hand in hand with the French.

General Alexander.

It fell to Alexander to tell Abrial and French General Fagalde, “Lord Gort has not told me to hold a sector of the Dunkirk bridgehead with French troops; he has told me that all English troops are to be evacuated.” Abrial and Fagalde felt (or pretended to feel) incredulity. Since the only record of the discussion was taken by the French, it inevitably bears a strong Anglophobic tone, noting that Alexander spoke “without conviction” and seemed embarrassed. Abrial spoke disparagingly of the British offer to evacuate French troops: “The 5,000 places which the English Navy has put at our disposal for the last two nights are insufficient to evacuate the 100,000 Frenchmen who are defending Dunkirk.” This was a gross exaggeration. There were at most 70,000 French soldiers left in the Dunkirk perimeter, and many of them were in the dunes and on the beach, trying to get away, hardly defending anything. Alexander replied that he was sorry, that all those who did not leave would be captured by the Germans, and that “everything that can be saved will be saved.” At this point a French naval officer, Capitaine de Frégate (Commander) de Laperouse, made exactly the kind of grand statement that never fails to irritate the British about the French: “No, General, it is still possible to save honour.”

The record then notes that General Alexander stared at the table in front of him, wiped his forehead and pretended he did not understand. Any French patriotic statement that featured “honor,” “glory,” or “the flag” was likely to produce among the British by this time a sharp counterreaction. Upon Alexander it produced a polite, but stubborn, determination to keep on repeating the order that Lord Gort had given him. He let the flood of inflated French rhetoric flow over him until Admiral Abrial finally said that the only way to resolve matters was to go and see Lord Gort at La Panne, at which point Alexander was forced to admit that Gort had already left for Dover at 4 p.m. Whoever was taking notes wrote down, at this point, “Long silence—disappointment.” Abrial dug the knife in a little deeper, determined to have the last word. “Since we cannot count on English co-operation, General,” he said, “I will fulfil my mission using French troops. We French have a mission which is to fight to the last man to save as many soldiers as possible from Dunkirk. Until we have achieved this goal, we will remain at our posts.”

Others reported that when Alexander was told that he should place three of his divisions so as to support the French resistance he had laughed and said, “You must be joking!” but this does not sound like Alexander. As for Abrial, far from fighting personally to the last, he was evacuated, received in audience by King George VI, returned to France to become an important figure in Pétain’s collaborationist government, then condemned to ten years of forced labor in prison after the war. The French taste for passionate patriotic rhetoric (and for having the last word, historically speaking) and the British preference for the stiff upper lip and steely avoidance of public demonstrations of emotion had hardly ever been in sharper contrast—each nation lived up to the other’s unflattering stereotype.

Despite these age-old differences of national character, each of the allies did more than the other had expected. If a substantial number of French units had not fought on to protect Dunkirk Harbor from May 31 to June 3, the evacuation would have had to be cut off. And in the end, the British would take off about 140,000 French soldiers, as compared with 198,000 of their own. Of the 140,000 only 3,000 would eventually choose to join de Gaulle’s Free French forces; the rest were repatriated to France to rejoin the battle and mostly ended up in German prisoner-of-war camps for the remainder of the war.

_________________________

* Desmond Morton was Churchill’s adviser on secret intelligence and Professor Lindemann (later Lord Cherwell) was Churchill’s adviser on scientific matters. They, along with Bracken, were thought to be overbearing, impatient with minds less quick than their own, and a bad influence on Churchill.

† The yacht’s name was pronounced “Chumley.” Trinder loved to make fun of the English upper-class tradition of names that were pronounced altogether differently from the way they were spelled, and would introduce himself as “Trinder, that’s spelled T-R-I-N-D-E-R, pronounced Chumley.”