ONE

Melting Snow

All the way to heaven is heaven itself.

In the fall of 1980, after I completed Zen training in Los Angeles with my teacher, Maezumi Roshi, I came to the East Coast with the intention of establishing a Zen arts center—a place where Zen training would be used as the vehicle for studying, enhancing, and cultivating a creative life.

The Zen Arts Center opened in Mount Tremper in October of 1980. Its main thrust was the practice of art within a Zen context.

Art had been a passion of mine since I was young, but its deep connection to my spiritual journey didn’t become obvious until much later. I started photographing when I was ten, and by the time I’d reached my mid-thirties photography had become an important part of my life. While working as a research scientist, I began teaching photography part-time at a local college. Spirituality was not in the picture—at least not overtly. The first time these two areas overlapped was in the late 1960s when I traveled to Boston from New York to see a photography exhibit titled “The Sound of One Hand,” by Minor White.

I didn’t yet have any sense that art might be a doorway to serious and transformative spiritual practice, but something more than good technique drew me to Minor’s work. Minor was a “straight photographer”: he didn’t manipulate his prints during the developing process, yet his images transcended their subject. Looking at his photographs, I felt myself being pulled into another realm of consciousness. Minor’s work pointed to a dynamic way of seeing, a new way of perceiving.

My life has been the poem I would have writ,

But I could not both live and utter it.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

One day in 1971 I received a letter from Aperture magazine announcing a workshop that Minor was giving at the Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, Connecticut. I took one look at the price and threw the letter in the garbage. A friend saw me, and she picked it up.

“Isn’t this the man you’re always talking about?” she asked. I nodded. “Then why are you throwing the letter away?”

“I don’t have the money to pay for it.”

“Send it in, John,” she said. “Something will come up.”

And, miraculously, something did. A month later a tax refund that I had completely forgotten about arrived in the mail. I sent in my portfolio, along with my date and place of birth so an astrologer could determine whether this was an auspicious time for me to do the retreat. With the acceptance letter I got the workshop’s reading list. It consisted of three books: Carlos Castaneda’s A Separate Reality, Eugen Herrigel’s Zen and the Art of Archery, and Richard Boleslavsky’s Acting: The First Six Lessons. Nothing on photography. What did my astrological chart or these books have to do with photography? At the time I was making my living as a physical chemist, and my rational, highly critical mind did not take well to these requests. But I really wanted to study with Minor, so I went along with what he asked.

When I arrived at the Hotchkiss School I saw that there were sixty participants, ranging in age from eighteen to seventy. Minor greeted us as we arrived. He was a striking figure, well over six feet tall, with a flowing mane of white hair. He moved quietly, gracefully, and when he entered a space, he filled it completely.

This oceanic feeling of wonder is the

common source of religious mysticism, of

pure science and art for art’s sake.

ARTHUR KOESTLE R

The first full day of the workshop began at four in the morning. The sound of a bass drum moving down the hallway arrived without warning. It was pitch black outside. How are we going to photograph in the dark? I wondered. Drowsily, I dressed and filed outside with the others. We gathered on a grassy field and a modern dancer began to lead us through a series of exercises. Everyone was participating, including Minor.

I turned to the man next to me. “Why are we doing this? What does this have to do with photography?”

“Ssshhhhh. Just do it,” he said.

I had paid hundreds of dollars to study photography with Minor, and I wasn’t about to spend the week undulating in the dark! Furious, I stormed away.

Back in my room, I started to pack my things. Dawn was breaking, and the line of dancers caught my eye as I passed the window. They were spread across the length of the field. I took the camera, screwed on a telephoto lens, and began to shoot, feeling very pleased with myself. They can do whatever they want. I’m going to photograph. That thought perfectly summarized where I was at that time in my life: standing apart, looking at the world through a lens, like a voyeur.

After the morning session, a group of students led by the dance instructor came to my room to convince me to stay. “You’re not giving it a chance,” they said. “You’re copping out.” I could have defended myself, but I was moved by the fact that they even cared whether I stayed or left. And deep down I knew that I couldn’t just walk away. I wanted so badly to learn to see the way Minor did, to photograph my subjects in a way that didn’t render them lifeless and two-dimensional.

As the days unfolded I woke up before dawn, meditated, and danced with everyone else. We attended lectures and did various exercises. We didn’t even touch our cameras for the first day or two. Then Minor began to challenge us with different questions that dealt with our way of seeing ourselves and the universe, questions that needed to be resolved visually.

One of these assignments was a turning point for me. On day four of the workshop, Minor told us to photograph our essence. “Don’t photograph your personality,” he explained. “Try to go deep into the core of your being. Photograph who you really are.”

Who I really am? I was absorbed in this question as I walked outside and sat in the field underneath a sprawling oak. I suddenly started sobbing. I couldn’t stop, and I had no idea why. Somehow, that seemed terribly funny, and I began to laugh. I kept laughing until I was exhausted. Who am I? That question repeated itself over and over in my mind.

Back in my room, I packed my 4 × 5 camera and a small backpack, prepared to stay out overnight in order to resolve this question. I set off for the nearby forest and began wandering. Minor’s instructions echoed in my mind: Venture into the landscape without expectations. Let your subject find you. When you approach it, you will feel resonance, a sense of recognition. If, when you move away, the resonance fades, or if it gets stronger as you approach, you’ll know you have found your subject. Sit with your subject and wait for your presence to be acknowledged. Don’t try to make a photograph, but let your intuition indicate the right moment to release the shutter. If, after you’ve made an exposure, you feel a sense of completion, bow and let go of the subject and your connection to it. Otherwise, continue photographing until you feel the process is complete.

The state of mind of the photographer while

creating is a blank.....[but] It is a very active state

of mind really, a very receptive state of mind, ready

at an instant to grasp an image, yet with no image

pre-formed in it at any time.

MINOR WHITE

Minor’s language was foreign to me. I had no idea what this resonance was supposed to feel like, or how I would recognize when my subject acknowledged me. I didn’t know if I could feel a sense of completion, or what I was supposed to do to “let go.” Yet, surprisingly, I was willing to trust Minor, and the process. Somehow, I intuited that I could do what he had asked. More importantly, I knew that I had to do it in order to answer the question.

Around noon I came to a beautiful gully and decided to rest. I built a small fire, leaned against a rock, and was eating my lunch when I sensed someone’s presence nearby. I looked up and saw the elegant figure of a man standing at the top of the ridge, the sun glowing behind him. He climbed down the rocks toward me, and I recognized John, a modern dancer and one of Minor’s senior students. I had been impressed with John since the beginning of the retreat. He would often photograph as he danced, leaping and turning in the air with a Polaroid camera in his hand. Like Minor’s work, John’s photos made me realize that there were other ways to photograph, other ways to see that were not so rational or linear.

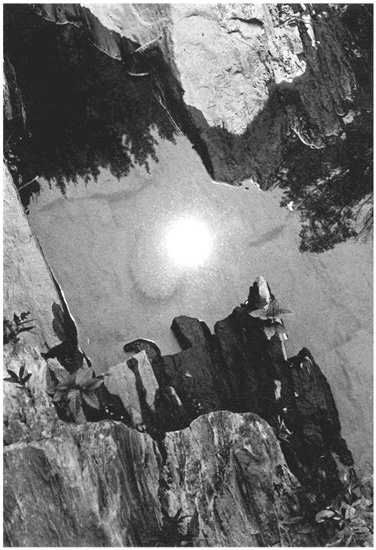

I invited John to join me and offered him a cup of tea. As soon as he sat down, I started jabbering about anything and everything. In the middle of my rant he abruptly whispered, “Listen! Listen!” In the silence I heard a faint tinkling. Intrigued, I picked up my camera and headed off toward the sound, leaving John behind. I soon found myself in thick, dark woods. A brook trickled through the mossy rocks. Light streamed through the trees; bright reflections danced on the water in the surrounding darkness. Enchanted by the scene, I stayed by the brook for an hour or more, completing several photographs in a slow, methodical, almost meditative way.

When I returned to the gully John was gone, and there was no sign of him ever having been there. The teacup was still in my knapsack, completely clean. There were no crumbs on the ground, no traces of him anywhere. It was as if our meeting had never happened— in fact, I wasn’t sure that it had.

I packed up and continued my wandering. As the sun passed the zenith and began its descent across the sky, the light that filtered through the canopy of trees became softer and warmer. None of the photographs I had taken so far seemed to touch the essence toward which Minor had pointed me.

Again, I heard Minor’s voice in my head. Photograph who you really are. I was looking at the ground, navigating over big roots with the heavy camera on my shoulder. I looked up and saw a tree standing a few feet away and off to my right which riveted my attention. It was an ancient hardwood with a gnarled trunk. Something about the way the light spilled over it drew me nearer. I approached it, bowed, set up my camera, and sat down on the ground next to the tripod, waiting for my presence to be acknowledged. I sat as still and quietly as I could, with my hand on the shutter release. Briefly, I wondered how I was supposed to know when to make the exposure. That’s the last thing I remember.

Hours later, I realized I was shivering. The sun had set behind the mountains and the afternoon had turned cold. Somehow, time had vanished for me. I slowly rose, aware that something deep inside me had shifted. The questions I had been struggling with during the workshop—all of my life, for that matter—had melted away. I felt buoyant and joyful. The world was right; I was right. I didn’t even know whether I had taken a photograph of the old tree, but at that point it didn’t really matter.

I headed back to the school, for an appointment I had with Minor to discuss my work. He was sitting on the porch outside his room, waiting for me. Settling next to him, the list of questions I had prepared earlier in the week no longer seemed relevant.

He looked at me and said, “You had a good day, didn’t you?” I smiled, and he smiled, too.

“What would you like to talk about?” he asked.

“Honestly,” I said, “I don’t have anything to say.”

“Good,” he replied. “Then let’s just sit here together.”

The days that followed deepened my appreciation for Minor and his teachings. Something had opened in me, and the techniques and activities of the workshop started to make sense. Minor was guiding us to go beyond simply seeing images. He was inviting us to feel, smell, and taste them. He was teaching us how to be photography.

As I was leaving, I felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude for Minor’s teaching that I didn’t know how to requite. When I said this to Minor, he simply said, “You’re a teacher, right?” I nodded. “Well, then teach.”

For a while this is what I did. I was very productive at first. I was seeing and photographing in a new way, and the workshops I taught around the country reflected a deeper understanding of myself as a photographer. But as the months passed, this new way of seeing and the feeling of peace that accompanied it receded, and my feelings of wholeness and well-being began to fade.

I tried to regain my balance by re-creating everything we had done during Minor’s workshop. I read books on religion, spirituality, and philosophy. I stood on my head, ate vegetarian food, and meditated. I listened to the music that Minor had played for us. I kept coming back to the questions: What had allowed the world to disappear so completely when I sat in front of the tree? Why did everything feel so right after that? Why did I feel at peace? And how did everything become cloudy again?

Do not go where the path may lead, go instead

where there is no path and leave a trail.

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

I then set out on a crooked path to find the answers to these questions, not knowing that this path would lead me to the mystical tradition of Zen and a new way of understanding art. But the first step on this path was to see if Minor could help me to make sense of what I was going through, so that’s where I started. Feeling a little nervous, I gave him a call. Without hesitation, without even asking me for a reason or even pausing to think it over, Minor responded. “Come,” he said generously, “we can have dinner and talk.”

Minor’s large two-story house in Cambridge was meticulously clean and sparsely furnished. It was sectioned into dormitories and studios for Minor’s apprentices, including a state-of-the-art darkroom facility equipped for archival printing and framing. Minor divided his time between teaching photography at MIT and maintaining this apprenticeship program, reminiscent of the traditional way in which artists and artisans learned art from a master. The training was rigorous and experiential, an extension of what I had encountered at the workshop.

Minor and I sat down to talk, but I was too shy to bring up my feelings of loss and confusion. Instead, we discussed music, art, philosophy, and some of the exercises we had done at the workshop. Hours passed, and just being in his presence somehow helped bring me back to the openness I had so painfully missed. Later, I would see how he had readied me, once again, to see what was right in front of me. He helped me to return to a state of “not knowing,” a willingness to trust what the next moment would bring.

Back in the hotel lobby later that night I noticed a poster for a conference on visual dharma at the Harvard Divinity School led by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a Tibetan Buddhist teacher. The poster must have been there when I’d passed through the lobby earlier that day, but I’d been too preoccupied to see it.

Various religious teachers were presenting, among them a Zen master who would demonstrate the “Way of Tea.” I knew in my gut that I needed to be at that conference. This was my next step, though I still had no inkling where I was heading.

The Saturday evening conference brimmed with excitement. Three hundred people filled the hall, many of them graduate students from the divinity school, and other students and teachers of various spiritual traditions. The highlight of the evening for me was the tea ceremony conducted by Eido Shimano from Dai Bosatsu Zendo, a Zen monastery in upstate New York.

As the stage was being prepared with the tea implements, I found myself oddly charged with anticipation. Eido appeared dressed in full robes. I was struck by his precise movements, his strong yet graceful presence. He walked slowly across the stage, knelt on a tatami mat and presented a brief overview of the Zen arts, using an example of Zen calligraphy hanging behind him and a small flower arrangement. He then led us through a fifteen-minute guided meditation in preparation for the tea ceremony. During the meditation, my body calmed. I felt relaxed, yet as solid as a rock. It was as if I had been drawn into a deep well, and a vast openness held me.

I watched closely as Eido prepared a cup of traditional powdered green tea. On the surface I saw someone simply preparing and drinking a cup of tea, but I sensed that the whole procedure had a much deeper significance. Eido’s movements were smooth and unhurried. He added boiling water to a scoop of tea he had placed in the bowl. He whisked the tea into a froth, bowed to it, lifted the cup and placed it on the palm of his hand, rotating it two times. Then he said to the audience, “I drink this tea with everyone.” He drank the tea in two sips and a final slurp. Then he carefully cleaned the tea implements and returned them to their tray. An assistant cleared the stage as Eido continued to sit in a meditation posture. He then opened the floor to comments and questions.

“I’ve tried to meditate, but I find it essentially boring,” said someone.

“Boring?” said Eido. “Boring? What does this mean, boring?” People shouted out definitions. “Oh, oh, oh,” said Eido, slapping his thigh. “I understand. . . . ‘Boring!’ ” He began to laugh and laugh, so heartily that it became contagious. The questioner began to laugh, too. In a few moments, the entire hall was caught up in laughter. Then, abruptly, Eido stopped laughing, folded his hands on his lap, lowered his eyes, and became silent again. After a pause, he softly said, “Next question.”

“I find myself agitated most of the time,” said a young man, “so it’s difficult for me to sit. What would you suggest I do?”

Eido reached for the pitcher of water that was sitting next to him. He lifted it with a swift jerk, causing water to spill. “What can I do?” Then he jerked the pitcher to the right. Again water spilled. “I don’t know what is happening.” Again to the left. “I can’t settle down.” Again to the right. Suddenly, he held the pitcher high above his head and in a deep voice shouted, “TIME TO SHUT UP AND SIT!” and slammed the pitcher on the floor. He reared back, stared at the pitcher, pointed at it, turned to the audience, and said, “Look, it’s still.”Again he folded his hands, lowered his eyes, and became silent.

I was hooked. There was something in what Eido represented that day—something that I intuitively knew had much to teach me. I had a feeling that these teachings were the reason for my visit to Minor. They were behind my impulse to go to the Hotchkiss workshop, and they were connected to what I had found in the woods sitting with the tree. Zen fit in with all of this. I didn’t yet know how, but I was sure of it.

Soft spring rain—

Since when

Have I been called a monk?

SOEN NAKAGAWA

After his question and answer session, Eido showed three slides of Dai Bosatsu Zendo while he talked about the training there. The slides were pathetic, underexposed, drab, and poorly framed. One was slightly out of focus. This man needs a photographer, I said to myself. I could have said, I need a teacher. But I just wasn’t ready to admit that yet. Instead, I told myself that I was going to help him.

After Eido’s presentation, I pushed through the crowd that had gathered around him onstage. I tugged at his sleeve and asked him for the monastery’s phone number. I wrote it down, feeling with absolute certainty that the way had opened up for me.

Dai Bosatsu Zendo, literally “Great Bodhisattva meditation hall,” was a three-hour drive from where I was living at the time. Pulling off the main highway, I followed small country roads that got narrower and narrower. I passed by the monastery gatehouse and proceeded up a very steep dirt road that wound through a beautiful forest to Beecher Lake—named for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s family, which had owned the property. At the lake’s edge stood a rambling nineteenth-century house. Up the hill, construction was under way for a new Japanese-style monastery building.

I parked and walked up the driveway to meet the head monk, who knew I was coming. He briefly described the lay of the land, and invited me to spend as much time photographing as I needed. That day I walked through the woods, following streams, circumnavigating the lake.

I returned to the office at dusk to ask the head monk if I could come back the next day. I told him this kind of photographing would take some time: several weeks, perhaps even months. I simply didn’t want to leave. The monk said it was fine for me to come back and asked if I would like to join them for dinner and the evening period of zazen, or seated meditation.

So began a ritual that continued for several years. I spent three or four days each week at the monastery, at first photographing, and then, later, as part of the lay sangha (the community of practitioners).

One evening, a senior monk said that Soen Nakagawa Roshi, Dai Bosatsu’s founder, had arrived from Japan. “Would you like to go to dokusan with him this evening?” he asked. By this time I was familiar with the language of Zen training, and knew that dokusan meant a face-to-face meeting with the abbot or Roshi (“old teacher”), so I said yes.

That evening, after the sitting period had begun, the dokusan line was called. When my turn came, I entered the dokusan room, prostrated myself to the altar, and stepped in front of the cushion where I’d been told Soen Roshi would be sitting—but the cushion was empty. I had no idea what was going on. I thought for a moment that I had walked into the wrong room. Still holding my hands palm to palm together in gassho in front of my face, I peered around the darkened room. “Roshi? Roshi?” I called out in a soft voice. Only then did I notice the master, sitting silently in a dark corner, watching me.

I walked over, bowed, and kneeled before him. He pierced me with his gaze, drinking me in.

“Please teach me,” I said to him.

“Namu dai bosa,” he said in a deep, resonant voice. “Do you understand?”

“Yes, I do.” I had chanted those words many times with the sangha. “Be one with the great bodhisattva.” I nodded again.

Soen repeated, “Namu dai bosa. Now, you say it.”

In a squeaky little voice I repeated, “Namu dai bosa.”

“From the hara!” he commanded and poked me below the navel with a long stick that he had in his hand, the kyosaku or waking stick. “From here!” I repeated it, this time with a little more strength and resonance. “Again!” he growled. “Again!” Finally he relented, “Ah, good enough,” not pushing me any further. “Namu dai bosa,” he continued. “Every day, all day. Namu dai bosa in evening, Namu dai bosa in morning, Namu dai bosa waking up, Namu dai bosa going to sleep. Whole body and mind Namu dai bosa.” As he spoke he reached down and rang his bell, ending the encounter.

“Namu dai bosa” embedded itself in my consciousness. I found myself following Soen’s instructions as closely as I could. Whenever my mind was not engaged with something, it was engaged with “Namu dai bosa.” I chanted it morning, noon and night, when I photographed, when I was agitated or scattered.

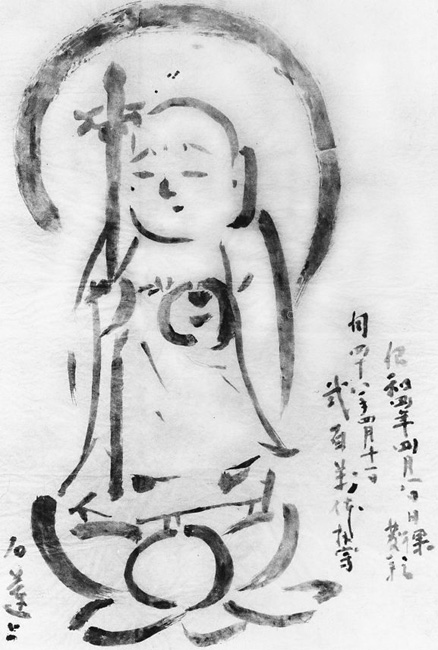

Early one morning after liturgy at Dai Bosatsu, I joined two other students to watch Soen create a calligraphy. Soen, an impish man of sixty-five, was a bit over five feet tall with a shaved head. He was always dressed in robes. Portraits show him as serious, even severe but, in truth, Soen was extremely playful and not just a bit eccentric. One moment, his deep, gravelly voice would boom with great dramatic effect, the next, his craggy face would soften, breaking into the sweetest of smiles.

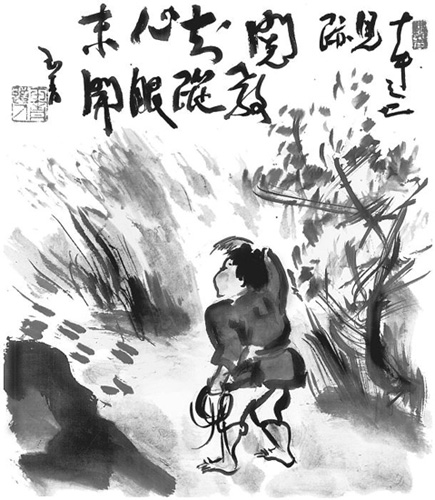

Soen entered the room, carrying a tray and a roll of sumi-e paper. He smiled at us and bowed, then spread out a long sheet, anchored the edges with small stones, laid out his brushes, and began to make ink. He added water to the ink dish and then slowly and quietly began rubbing the ink stone in the water against the rough inner surface of the dish. The ink stone, which is made of carbon soot held together with pine resin and compressed into a rectangular stick, is scented with a sweet perfume that fills the air as the ink is ground. Eyes lowered, Soen continued to work the stone against the dish.

The ink slowly thickened, finally reaching a consistency that satisfied him. He wet his brush and sat with it in hand, poised over a long, rectangular white sheet of paper. With a single smooth gesture, the blank space leapt into dynamic tension with the stroke of the brush. The second, third, and fourth strokes laid out characters. Each stroke complemented the previous one, activating the blank space around it.

Where the spirit does not work with the hand

there is no art.

LEONARDO DA VINCI

Soen diluted the ink by dipping the brush tip in water, and added light gray characters to his work. In the same gray ink he signed his name, in Japanese and Roman characters, and added his seal. He bowed to his painting, then to us. We returned his bow. I knew then that the path I had been following had led me step by step to this moment, this teacher, this bow.

Snow of all countries

Melting into

Namu dai bosa

SOEN NAKAGAWA