TWO

Mountains and Rivers

One of the gifts I received from Soen Roshi was a sense of how the Zen arts live in a person. He awakened in me a hunger to study how this art worked on the human heart, and how the tradition of the Zen arts might be translated into my own art and teaching.

Soen was not only a Zen master. He was an artist, a poet, painter, Noh drama actor, and the most recent embodiment of one of the most important historic lineages of the arts of Zen that went back to the seventeenth century. Soen was the abbot of Ryutakuji, founded by one of Zen arts’ most significant figures, Zen master Hakuin. Hakuin is celebrated as the revitalizer of Rinzai Zen in Japan and one of the most prominent masters in the tradition of zenga (Zen painting).

Hakuin was the beginning of a long line of Zen masters who have passed down through successive generations the tradition of zenga as a visual way of teaching. Of all the masters whom I could have met in my early encounters with Zen, it was my good fortune to meet a holder of this long tradition of the sacred arts of Zen.

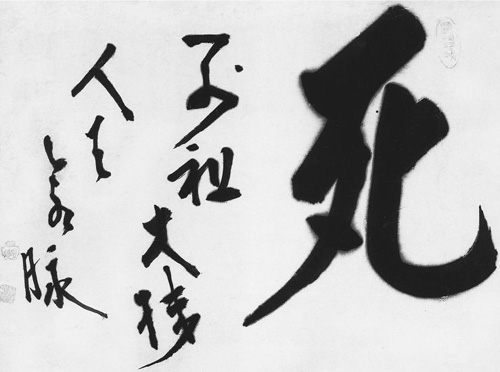

As I worked with Soen, I saw the living spirit of Hakuin reflected in the many paintings that decorated the walls of Dai Bosatsu. Hakuin’s powerful works of brush and calligraphy were charged with energy, yet they were still somehow tranquil. His art spanned a wide range of subjects not usually associated with religious art: acrobats and animals, household utensils and courtesans. His calligraphy contained Zen teachings, quotes from the scriptures, but also nonsensical rhymes and quite a few jokes. Explaining a phrase of the Heart Sutra—one of Mahayana Buddhism’s key texts, chanted daily in Zen monasteries—that reads “form is emptiness,” Hakuin said, “A bowl of delicious soup is ruined by two lumps of rat shit.” Yet Hakuin’s art was never silly or simplistic. Even the most seemingly innocuous phrases contained a hidden barb, a piercing question.

Sometimes, Hakuin’s calligraphy was direct, uncompromising. One calligraphy reads: “A single arrowhead breaks the three barriers,” painted in bold, striking brushstrokes. It shoots the implicit question right into the heart of the viewer: What is the single arrow that can pass through every obstruction, every barrier of greed, anger, and ignorance? We can almost hear Hakuin demanding, “Don’t tell me! Show me!”

As I spent time at Dai Bosatsu, I began to suspect that the key to the profound qualities I was seeing in Zen art was Zen practice, and that zazen—Zen meditation—was its foundation.

I had heard that as a young man Soen Roshi used to sit zazen high up on a tree to train himself not to fall asleep. It was said that once, when Soen was sitting at Dai Bosatsu Mountain in Japan (for which the monastery is named), he fell out of a tree and his head was pierced by a sharp piece of bamboo. Yet this incident didn’t stop him from sitting.

During an intensive meditation retreat at Dai Bosatsu, I witnessed Soen Roshi’s amazing capacity to sit perfectly motionless in zazen for long periods. I saw him sit through the day, into the night, and then on through the next day. Curious, I got up in the middle of the second night to see if he had finally gone off to rest, but there he was, still sitting in the empty zendo. Peter Matthiessen, in his book Nine-Headed Dragon River, wrote that when he was assigned to clean the zendo for work practice, he sometimes had to dust around Soen sitting in meditation.

Soen’s capacity was extraordinary, to be sure, but the power of his meditation wasn’t confined to the zendo, or the zazen posture. Soen’s stillness when he sat was no different from the stillness that preceded his brushstrokes when he created a calligraphy. His every movement was poised, centered, completely present. This stillness and depth was also present in his poetry, which earned him the honor of being considered by many to be the Basho of the twentieth century. One of Soen’s haiku reads:

Early morning,

Birth—

tiny dew drop, tiny plum

All artists are of necessity in some

measure contemplative.

EVELYN UNDERHILL

When Soen wrote a poem or did calligraphy, I could see his whole being shift. He became very quiet, motionless, and I could feel the same stillness descend on me as I watched. Though what I saw in front of me was just a Chinese character, each time I felt as if the piece of art was all there was to see. It filled the universe. Soen disappeared, I disappeared. There was no longer any separation between the art, the artist, and the audience. It was a familiar feeling, similar to the time I had spent with my tree.

While I studied with Soen, I kept working on the slide show of the monastery, and when I finished it I showed it to him and the rest of the community. Millie Johnston, a wealthy art collector involved with various Buddhist groups in the United States, was in the audience. She suggested that I get in touch with Trungpa Rinpoche and offer to teach photography at his new university, Naropa, in Boulder, Colorado.

I was given the job and traveled to Colorado to teach a summer course. One morning shortly after I arrived, I was sitting out on the balcony of my apartment when I saw the university staff moving furniture into the apartment next door, recently vacated by a professor of Hinduism. One of the movers was carrying several Japanese scrolls.

“What’s going on?” I asked him.

“The Hindus are out. The Japanese are in,” he said.

“Who’s coming?”

“Taizan Maezumi, a Zen master from Los Angeles,” he replied.

When Maezumi Roshi arrived, I went next door to pay my respects. I introduced myself and told him I was studying with Soen. That evening, one of his senior monastics knocked on my door and said Roshi wanted to invite me over for a dinner of Kentucky Fried Chicken and sake. I went with him and discovered a full-blown party. For some reason, Roshi took a liking to me and insisted that I stay beside him through the evening. As we sat together, an unusual encounter ensued.

“Daido,” Maezumi Roshi used the Buddhist name that Eido had given me. “Ask me!” He leaned close.

“Ask you what, Roshi?” I said.

Roshi turned his head away and was silent. Leaning close again, he said, “Daido, tell me.”

“Tell you what, Roshi?” Again he turned away and was silent.

This went on for hours. At one point, I surmised that what was happening was a classic dharma encounter that required some kind of a Zen response on my part. So the next time he said, “Tell me,” I lifted the glass of sake to my lips, took a swig, and said, “Aaaaah!” slamming the glass on the table. I looked at him. He made eye contact with me, and with an impish grin, pinched his nostrils together, turned his head away, and made the sound, “Phew!”

Some time around two in the morning I finally convinced him that I had to leave. I began cleaning up the mess we’d made, but he stopped me, said it wasn’t necessary, and pushed me out the door. I was surprised and disappointed that a Zen master would leave such a mess, but I was also exhausted, so I let it go. I went back to my apartment and lay down on the couch in my living room, not wanting to wake my wife. I had barely drifted off to sleep when there was a knock. Maezumi Roshi stood at my door, wide awake and immaculately dressed in robes, his head freshly shaven. “Roshi!” I exclaimed.

“Come with me,” he hissed. It was an order.

I followed him back to his apartment. The place was spotless. The low table in the dining room had four bowls and the implements for a formal tea ceremony. “Come,” said Roshi, gesturing for me to sit down. “We will have tea.”

He spooned powdered tea into a bowl and whisked it into a froth. “Soen Roshi,” he said, placing the bowl before one of the empty seats. He repeated the process and put that bowl in front of the other empty seat, saying, “Yasutani Roshi.” Yasutani was Maezumi’s teacher, who had recently passed away. The third bowl he presented to me. Finally, he whisked one for himself.

The moment I touched the bowl to my lips and took a sip of tea, I felt something piercing, like a long skewer moving through all space and time. It skewered Minor White, Eido, Soen, Maezumi Roshi and, finally, me. I was so moved, tears of gratitude filled my eyes. Embarrassed, I glanced up and saw that Maezumi Roshi, too, had tears rolling down his cheeks.

I put the bowl down and through my tears watched Roshi as he completed the ceremony. Wanting to express my gratitude somehow, I stammered, looking for the right words, “Roshi, I—” He covered my mouth with his hand, grabbed my elbow, and led me to the door. “Roshi—”

“Sssshhh,” he said. He gently pushed me out the door and closed it behind me.

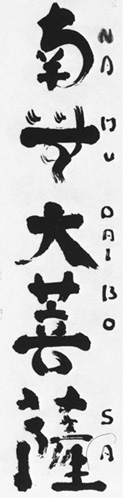

For the rest of Maezumi Roshi’s stay at Naropa we had no contact. I attended his talks, but he acted as if he didn’t know me. The last day, when he was ready to leave, Roshi came to say good-bye. I bowed and thanked him. He looked past me at a scroll of Soen Roshi’s, “Namu Dai Bosa,” hanging over an improvised altar I had set up. He turned to me and said he wanted to offer incense to Soen Roshi.

“But it’s only a silk screen copy,” I said.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said in a gruff, slightly annoyed voice. He offered incense, bowed to the scroll and then to me. He left, and I stood on the balcony watching him, until his car was out of sight.

At the end of the summer, I left Naropa and went back to a farmhouse on the Delaware River, where I had moved with my wife and two-year-old son. Our future plans were not well defined, and with winter approaching, my wife began to worry. “Something will come up,” I told her. “I’m sure of it. Maybe tomorrow morning after zazen, when we’re quiet, we can discuss it and figure out what we’re going to do next.” I felt an inexpressible certainty that where I was headed would become obvious.

The next morning, at the end of our sitting, the phone rang. I looked at my watch. It was seven-fifteen.

“Hello, Daido, this is Maezumi Roshi.”

“Roshi! What time is it there?”

“It’s a little after four. I’m about to go to zazen.” He paused for a moment.

“Daido, what is your relationship to your teacher?”

Surprised, I said, “I don’t know that I have a teacher. I was studying with Soen, but he went back to Japan. So I guess I don’t have a teacher. Why, Roshi?”

“Would you like to come to Los Angeles and study here?”

“Yes, I would love to. But we don’t have any money, and I have a family.”

“Let Tetsugen talk to you.”

He put Tetsugen Glassman, one of his senior monks, on the line. “We’ll pay for your trip,” Tetsugen said. “And you can bring your family.”

I talked to my wife, and soon after we packed all our belongings and headed to the West Coast. We left in the middle of a snowstorm and arrived at the Zen Center of Los Angeles before the December sesshin, the most intensive silent meditation retreat of the year. That was my formal entry into full-time Zen training under Maezumi Roshi, which would eventually lead me to become a Zen priest.

Moving to L.A. and studying in full-time residency with a teacher meant a major shift in lifestyle. The days were filled with meditation, morning, noon, and evening, the chanting of liturgical texts, caretaking the center’s buildings and grounds, ritual meals, and frequent meetings with my teacher—in short, all of the attributes of classic monastic training.

The central focus of my teacher-student relationship during this time was traditional koan study, a device unique to Zen. Koans are designed to short-circuit the intellectual process and to open up the intuitive aspects of our consciousness. To understand the vitality of koan study, one must understand that the question, “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” for example, is not a riddle or a paradox. It’s a question that has to do with the most basic truth. It’s no different than the questions, “What is reality? What is life? What is death? What is God? Who am I?”These questions deal with the nature of reality. They are questions that every religion ultimately addresses.

At the time, Maezumi Roshi was working on a book of commentaries on the teachings of Eihei Dogen, a thirteenth-century Zen master. Dogen was the founder of the Japanese school of Soto Zen Buddhism and one of the most highly regarded masters in the history of Zen. He has recently been discovered by the West and is widely respected, not only as a great religious thinker, but also as a great writer and poet.

Maezumi Roshi’s commentaries focused on Dogen’s “Genjokoan” (The Koan of Everyday Life). I was asked to create color photographs for the commentary. These needed to go beyond simple illustration of passages and bring the teachings to life in a visual way. Isn’t this what Hakuin and Soen did in their brush paintings? Can a photograph reveal the inexpressible aspects of the teachings of Zen in a visual way?

These questions became my work in the face-to-face meetings with my teacher. After presenting my understanding of a paragraph of “Genjokoan,” I would express it with a visual image. At the time, I had little sense of how this work would ultimately impact on my way of understanding the arts of Zen, as well as my own way of creating and teaching these arts.

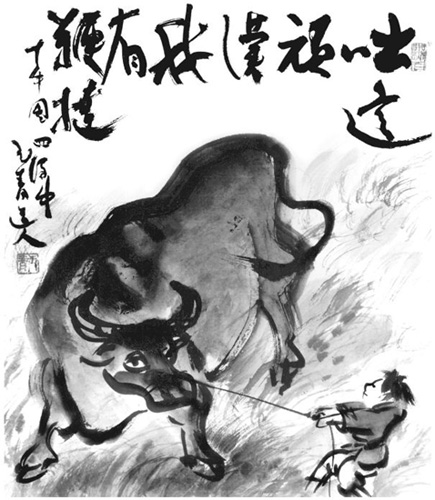

When we finally published The Way of Everyday Life, it was very successful and well received, so we decided to do a second book with another of Dogen’s works, the “Mountains and Rivers Sutra.” For Dogen, mountains and rivers themselves are a Buddhist scripture—a scripture that manifests the Buddha’s wisdom.

When I began studying this sutra, it was an obscure text. The only translation available was a doctoral thesis by Carl Bielefeldt. I got a copy of it from the university library and started to read and digest it. In the midst of this work, Maezumi Roshi told me to go to NewYork City to assist Tetsugen to establish a Zen center. The book was put on hold.

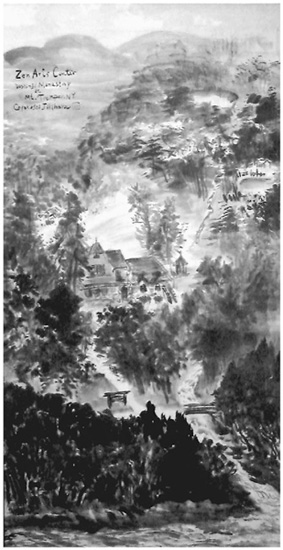

“After you help Tetsugen,” Maezumi said, “you can establish the Zen Arts Center you keep talking about.” I had, for some time, been contemplating using the arts as a way of getting people to appreciate Zen, and was hoping to establish a place for just such a purpose.

After about eight months on the East Coast helping Tetsugen, the opportunity finally presented itself to establish the Zen Arts Center. The building I purchased was located on a property with a mountain behind it and two rivers meeting in front. The auspicious nature of the setting reminded me of the “Mountains and Rivers” work that I had been doing with my teacher.

Although we say that mountains belong

to the country, actually, they belong to

those who love them.

EIHEI DOGEN

Soon after moving into the monastery, I picked up a copy of the Woodstock Times, a local newspaper, and saw, printed in bold type across the top of the second page, the first line of the sutra: “These mountains and rivers of the present are the manifestation of the Way of ancient buddhas.” A page-and-a-half-long story on the “Mountains and Rivers Sutra” followed. I was stunned.

I immediately went to the Times office and burst in on the editor.

“Can I help you?” he politely asked.

“How did you find out about Master Dogen?” I blurted out.

He looked me straight in the eye. “Doesn’t everyone know about Dogen?”

He added that a book titled Mountain Spirit had just been published by a local press. In it was the Bielefeldt translation.

Following that incident, I began to study the “Mountains and Rivers Sutra” with renewed enthusiasm. I went back to it regularly as I encountered the problems and questions that surfaced while I struggled to formulate a way of teaching the Zen arts at the center. I was trying to develop a Western form of the Japanese teachings I had inherited from my teacher, particularly with regard to the arts as a way of making the teachings palpable to the growing number of lay students that were coming to the center. Many were jazz musicians, painters, sculptors, and poets, all intrigued by the relationship between Zen and the creative process. This was reminiscent of secular artists seeking spiritual guidance at the monasteries of Sung China and Kamakura Japan.

The “Mountains and Rivers Sutra” and Dogen’s teachings kept resounding within me, and the early idea of the book that I had discussed with Maezumi Roshi began to re-form itself. I now saw the possibility of expressing the sutra as a film. It felt to me that the sutra needed to be expressed through visual imagery, sound, music, movement, and the words of Dogen.

I began working with one of my Zen students who was an acoustic composer and professor at Juilliard. We began working line by line with the sutra, treating each line as a koan in the same way I had worked with Maezumi Roshi on “Genjokoan.” When our understanding was in agreement, I would express it visually, and he would write a score for it. We slowly progressed through the texts, wrestling with Dogen’s profound language:

Because the blue mountains are walking, they are constant. Their walk is swifter than the wind. Yet those on the mountains do not sense this, do not know it. To be “in the mountains” is a flower opening within the world. Those outside the mountains do not sense this, do not know it. Those without eyes to see the mountains do not sense, do not know, do not see, do not hear this truth.

How could we express this visually? What did it mean to say “blue mountains are walking”? How could such a phrase be expressed musically? Line by line we worked to create a modern manifestation of these ancient teachings.

It became obvious that the music needed to return to the earth itself. A friend of the composer, a professor at the Manhattan School of Music, was brought into the process. He began recording the natural sounds of the mountains and rivers, the birds, insects, wind, rushing water, and he used these as the foundation for synthesizing electronic music that was folded into the score.

There are mountains hidden in jewels. There are mountains hidden in marshes, mountains hidden in the sky. There are mountains hidden in mountains. There’s a study of mountains hidden in hiddenness.

The acoustic composer called on two friends who were sopranos at an opera company to sing Dogen’s words. We were all pleased with the result, and joked about having created the first Zen opera.

The film was a success, and it went on to win awards. But the real success was the transformation of these students—the impact that Buddhism’s ancient teachings in modern form had on their lives. The acoustic composer received the Buddhist precepts. I gave him the dharma name “Kyogen” (Source of the Sounds). Both he and the electronic composer entered a whole new realm in their artistic expression that was precipitated by Dogen’s mystical vision. For me, it was the completion of the circuitous journey that had begun with Minor White and wound its way to the Zen Arts Center. The matrix for teaching Zen and the art of living a creative life had finally taken its shape.