FOUR

Seeing with the Whole Body and Mind

Seeing form with the whole body and mind,

Hearing sound with the whole body and mind,

One understands It intimately.

EIHEI DOGEN

“Whole body and mind seeing,” as Master Dogen refers to it, is the total merging of subject and object, of seer and seen, of self and other. This is, essentially, the experience of enlightenment. In “seeing with the whole body and mind” one goes blind. In “hearing with the whole body and mind” one goes deaf. And there is no way to describe this state of consciousness. The Heart Sutra takes up whole body and mind seeing by saying what it is not: “no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind; no color, sound, smell, taste, touch, phenomena; no realm of sight, no realm of consciousness.” But, as I said before, a person in such a state cannot function. He cannot get across the street without getting hit by a car, since he cannot differentiate between himself and the car.

In terms of spiritual practice, seeing with the whole body and mind is to “reach the summit of the mystic peak.” This may seem like a profound achievement, but in Zen, this is not the endpoint. The journey continues straight ahead, down the other side of the mountain, back into the world. It is in the ordinariness of our lives that this intimate experience of the self merging with the absolute can begin to express itself.

Again, the Heart Sutra: “O Shariputra, form is no other than emptiness, emptiness no other than form. Form is exactly emptiness, emptiness exactly form. Sensation, conception, discrimination, awareness are likewise like this. O Shariputra, all dharmas are forms of emptiness.” It is not until we have reached the place where the absolute basis of reality is informing our everyday existence that the Zen teachings become alive in us.

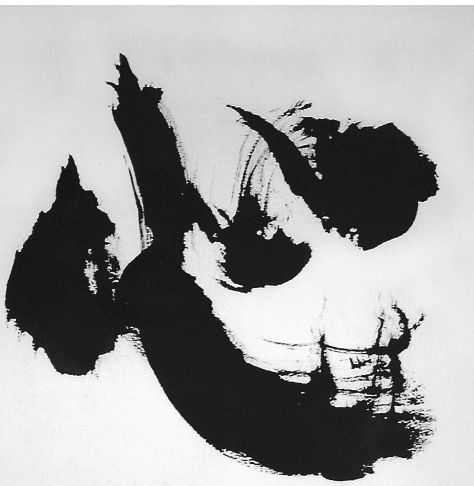

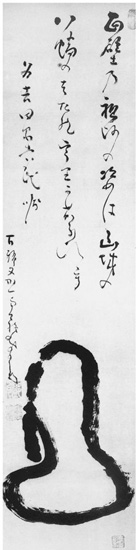

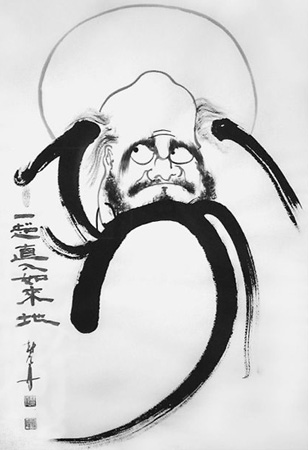

This meeting of the absolute and its manifestation in the world is clearly evident in the classic arts of Zen created by enlightened masters whose perception of the universe is as Dogen describes it.

But what does this mean to the artist or practitioner who has not yet experienced this realization? How can any of us gain entry into this unique way of perceiving the universe, where every breath is the first breath, every sight and sound is fresh, penetrating the universe, reaching everywhere?

. . . Music heard so deeply that it is not heard

at all, but you are the music.

T.S. ELIOT

At one time or another, each of us has experienced this way of perceiving. It comes upon us unexpectedly. Suddenly the music moves into our being and our body responds. There is no thought, judgment, or conscious effort. The music freely passes through us. We pick up a brush and the painting flows from its tip. The poem creates itself, almost without effort.

Then why can’t we live our lives in this way, unhindered, unfiltered? Why do we so consistently get caught up in our ideas, in the belief that we know exactly how things are?

All creatures experience the universe through the senses. And at every moment, a different universe is being created by each being. A spider, for example, feels the universe through its legs, which touch the key strands of its web. It knows when it’s raining, or when food is available. It doesn’t think to itself, “That’s not a fly on the web. That’s rain.” Yet it knows. The spider doesn’t deliberate about what kind of fly it would like to eat or criticize the rain for trying to deceive it. A spider just does what it does, effortlessly and spontaneously.

For most of us, however, our habitual way of perceiving is not so simple. Our universe is filled with internal dialogue, analysis, evaluation, classification. We choose knowing over direct experience. Yet, in knowing, we kill reality, or, at least, we make it inaccessible. We live and create out of our ideas, out of the apparent comfort of certainty that they offer.

Plants and animals, for example, are categorized according to their biological classification, their family, genus, and species. That’s the way science often functions. The multitude and complexity of life’s web, all its myriad forms, are placed into useful groupings and subgroupings. Northern white pine is Pinus strobus. This pine grows all over Tremper Mountain near Zen Mountain Monastery. It’s different than Pinus resinosa, which is Norway pine. Or Pinus virginiana, which is Virginia pine.

But what do these categories really say about the white pine I see each day as I come out of the front door of my cabin? It’s been a friend for more than two decades. It has witnessed my comings and goings. I’ve watched it dance in the mountain’s fierce winds. I’ve seen it shelter birds in a snowstorm, provide a branch for a red squirrel, feed a ravenous woodpecker. This tree, just like me, is an ever changing individual. It is easily recognizable from another Pinus strobus growing right next to it.

How many individuals do we miss in our daily experience because we’ve stopped seeing and started knowing? How much damage do we create in our confusion? James Watt, the U.S. Secretary for the Interior during the Reagan administration, said, during the debate over the giant sequoias in California, “What’s the big deal about these trees? You’ve seen one tree, you’ve seen them all.”

The poet Walt Whitman advises us: “You must not know too much or be too precise or scientific about birds and trees and flowers and water-craft; a certain free margin, and even vagueness— perhaps ignorance, credulity—helps your enjoyment of these things. . . .”

The less we know, the less we’ll try to intellectualize our experience. Intellectualization closes many doors. One of the beautiful aspects of Asian poetry is the vagueness of its languages. Chinese and Japanese characters tend to have broad implications and multiple meanings that depend on how they’re used. They don’t pin things down as precisely as English does.

“Do,” pronounced “dao” in Chinese, means “way,” “path,” “road,” or “track.” It’s the character used in the various arts of Zen, in which it refers to the principles of mental training and discipline. In Buddhism, “do” pertains to the teachings of the Buddha. In Taoism, it is the first principle of existence. In Confucianism, it is the ultimate basis of cosmic reason. In Japanese, there are many other characters that have the same sound, which opens the door to various—sometimes amusing, sometimes profound—plays on words.

Besides this built-in vagueness, we must also take into account the fact that Chinese and Japanese characters are used in a significantly different way within Buddhism and Zen than in ordinary usage. Their meaning can be even more removed from the vernacular.

A professor of philosophy who was raised in China as a Buddhist approached me at the end of the morning service at Zen Mountain Monastery. She excitedly exclaimed that although she had been chanting the Heart Sutra in Chinese every day for forty years, it wasn’t until she heard the English translation that she “finally comprehended it.” The specificity and definitiveness of the English language allowed her to grasp the meaning of the chant. She might have understood it, but by pinning down the sutra’s message, she was left with a concretized version lacking poetry, mystery, and spaciousness. Perhaps the experience was satisfying, but I’m afraid the sutra probably lost much of its subtle profundity.

This need to categorize, to understand our world, is an inherent part of being human. Take a simple object—a cup, for example. When I reach out and touch the cup, the moment my hand makes contact is pure touch; the sensation is unprocessed. But within milliseconds my mind needs to identify the object, and so the intellect kicks into gear. It sorts through its memory bank of previous contacts, just like a computer looking for a bit of information. Is it cold? Is it warm? Is it hard? Is it soft? Is it delightful? Is it furry?

Once we’ve identified the cup, the process of perception stops, and all other aspects of the cup are lost to us. We tacitly believe that when we’ve got a name for something, we know it. And once we know it, we stop noticing its qualities. We stop noticing the fact that it is perpetually changing and how it changes; we disregard what else it is. The art of attention developed in zazen lets us stay alert to the moment. It shows us how thoughts arise and interfere with our seeing. We can affect that process by letting go of thoughts and returning our attention to the immediacy of the breath and its pure sensation. We keep beginning, breath by breath. When that kind of attention informs our life, we see beyond our ideas into reality itself.

Practice: Direct Experience

The tea ceremony in Zen involves experiencing a cup of tea, but an important part of the ritual takes place at the end of the ceremony, when the tea master brings out all of the implements used for the guests to examine and appreciate. The tea bowl is presented as a unique work of art, without peer. It is examined by the guest both visually and tactilely.

See for yourself if it is possible for you to take up an ordinary teacup and just experience its physical existence, without naming, analyzing, judging, or evaluating it. Just feel it. See it. Touch it. Experience it without the mind moving. When you find your mind moving, acknowledge the thought, let it go, and come back to the cup in the same way that in zazen, when a thought arises, you acknowledge it, let it go, and come back to the breath.

Usually we don’t really look at anything at all.

CHOGYAM TRUNGPA

You’ll find that the more you repeat this, the more you’ll develop the ability to experience things directly, without evaluation. You’ll be able to just see, hear, feel, taste, smell. And, as your attentiveness and awareness increase with this practice, they will appear in other areas of your life and art. You will begin to notice little things that you have been seeing every day but barely noticed in passing. This kind of mindfulness is a state of consciousness that is free of tension and focused on the here and now, with no attempt to name or even understand what is being perceived.

An ancient Chinese master was asked for a teaching by one of his students. The master mixed some ink and readied his brush and paper. He sat in the presence of the blank sheet, then in a single breath executed the character for attention. He looked at it briefly and gave it to his student. “It’s beautiful! But what does it mean?” said the student. The master took up his brush, executed the same character again, and presented it to the student. “Yes, yes, I understand,” asked the student, “but what does it mean?” The master shouted, “Attention means ATTENTION!”

When we truly pay attention, we see each object or situation for the first time—and it always seems fresh and new, no matter how many times we’ve encountered it before. We break free of our habitual ways of seeing.

Only that day dawns to which we are awake.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

Suppose you have to work in a garden, picking weeds, and instead of the boredom and distraction that an inattentive mind would soon create, you see each weed as the first weed and the last weed of your life. You pick a weed—first weed, last weed. When you put it down, you let go of it completely. The next weed you pick is totally new. You don’t know anything about it. You just pay attention. What does that mean? Attention means ATTENTION!

Practice: Caretaking

Create a simple practice for yourself using some routine task that you do every day, such as washing the dishes, sweeping the floor, or making the bed. Make an agreement with yourself to perform this task with total awareness. When you wash the dishes, just wash the dishes. As the Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh said,“You can wash the dishes in order to have clean dishes, or you can wash the dishes to wash the dishes.” The same is true of any other task that we do almost mindlessly. Try bringing to it a mindfulness that is not critical, evaluating, or analytical, but focused simply on being present in the moment.

To practice attention means that when a thought arises, we see it, let it go, and return to the breath, to pure sensation, to the activity in front of us. That willingness to return to simply doing what we’re doing while we’re doing it is enough to open our eyes and let seeing happen. It is actually a radically different way of living. When we’re not seeing, we get bored with our jobs, with our partners, with the day-to-day events of our lives. We keep inventing sports and challenges to keep ourselves excited.

Ordinary life has its own rush. We feel it when, being completely present, we step out into the world. There can be a rush in simply driving a truck or a bus, or digging a ditch, building a house, washing clothes, doing the dishes, but only if we don’t blanket the unknown manifestation of the moment with our preconceived notions. We just allow each event to be what it is, entering it completely.

For hundreds of years Zen artists have continually revisited the same limited number of themes in their work, yet invariably, their expressions are unique, fresh, alive, and fulfilling. Hakuin’s Bodhidharma is not the same as Sengai’s. Basho’s haiku are not the same as Ryokan’s, though the two masters often wrote about the same subjects. In the art of shakuhachi, the same piece acquires a completely different tenor depending on the mastery, and even the personality of the artist who plays it. The ceremony of tea is made up of a very specific and deliberate set of movements that does not leave much room for spontaneity. And yet the process is different each time it is practiced. It is given a particular life by the artist who creates it and the uniqueness of the moment of creation. The same is true for all art.

Most people have seen photographs of a sunset. But of the hundreds, thousands of photographs of sunsets, maybe one or two will stand out, will really grab us with their force. Why? What was the artist able to capture in such a way that the sunset became unforgettable?

My own photography students often complain that their photograph of a sunset did not at all translate into the image. But, I tell them, it’s not that there is anything wrong with the image. It’s just that they were photographing only one aspect of their experience: what they could see.

There are painters who transform the sun

into a yellow spot, but there are others who,

thanks to their art and intelligence,

transform a yellow spot into the sun.

PABLO PICASSO

We are usually only dimly aware—if we’re aware at all—of the converging of information from our senses when we experience an event. We’re so dependent on seeing that we tend to ignore what the other senses are communicating.

When we stand on top of a mountain, gazing at the sunset, we can clearly see the dazzling colors and shapes of clouds draped over the distant mountains. Yet, at the same time, we also feel the warm evening breeze touching our bodies, we smell the dampness of the mountain pines, we hear the sound of the wood thrush, we feel the cool earth under our feet. All of these sensory experiences contribute to our experience of the sunset.

It may be that we have to turn the camera away from the sunset and photograph our big toes, or some other image that evokes the totality of the experience of the sunset. This is not only true for photography, but for all the arts. The poet, the painter, or the composer who is locked into only the visual phenomena of the sunset may miss the heart of what was actually being experienced.

This is why whole body and mind seeing is so important. When we practice this whole way of attending and experiencing as we move through our daily lives—when we make direct contact with reality—we go beyond an ordinary way of seeing, of being, and touch the sacred dimension of our lives. To paraphrase Master Dogen: “In the mundane, nothing is sacred. In sacredness, nothing is mundane.” Evelyn Underhill wrote at the turn of the nineteenth century in her book Mysticism:

Contemplation is the mystic’s medium. It is an extreme form of that withdrawal of attention from the external world and total dedication of the mind which also, in various degrees and ways, conditions the creative activity of musician, painter and poet: releasing the faculty by which he can apprehend the good and beautiful and enter into communion with the real. [emphasis mine]

Be aware that the mystic is none other than each one of us. “Entering into communion with the real” does not mean entering some kind of esoteric state of mind. It is your mind, right here, right now. To contemplate is to use your ability to see directly, intimately, and to express through the creative process and your life what you see—not what you think you see, but what actually is.

I shut my eyes in order to see.

PAU L GAUGUI N

Practice: Experiencing Without Identifying

Have a friend put five or six small objects that can be held in your palm into a small wastebasket. The objects should represent various kinds of tactile surfaces. Without looking into the basket, reach in and take one of the objects. Now spend ten or fifteen minutes exploring it with your hands, your eyes closed. Feel every part of the object, but avoid trying to identify it. As thoughts arise, acknowledge them, let them go, and return to the object. After a few minutes, return the object to the basket and put it aside. Repeat this process at another time.

You’ll find that as you return to this handful of objects and examine them, you’ll begin to develop the ability just to experience the object directly, without the need to identify it. You can then extend this practice to other sensory experiences, such as visual images projected on a screen or sound images. Try to develop the ability to just see, just hear, just taste, just touch, just smell, just see a thought (but without processing it) without the need to give it a name or identity. This way of perceiving will then begin to translate into the way you express yourself through your art.