SIX •

Jeweled Mirror

Many artists spend a lifetime creating, exhibiting, and publishing their art, yet never know how their audience experiences their work. Professional artists who have published or exhibited know what the critics think of their art, or whether it’s commercially successful. But beyond that, do they really know what they’re communicating? What are the emotions their art awakens? The same questions apply to anyone who practices art as a hobby.

Our art is always communicating, and we need to be conscious of what its message is. Creative feedback offers artists an opportunity to get a sense of the impact of their work: the visceral, direct effect that they’re having on their audience.

It should be clear at this point that the process of quieting and focusing the mind is common to creative perception and creative expression. As we will see here, it is also the central element of creative feedback.

Evelyn Underhill, speaking about the mystic’s way of perceiving, describes the following exercise.

Look for a little time, in a special and undivided manner, at some simple, concrete, and external thing. This object of our contempla tion may be almost anything we please: a picture, a statue, a tree, a distant hillside, a growing plant, running water, little living things ..... Look, then, at this thing which you have chosen. Will fully yet tranquilly refuse the messages which countless other aspects of the world are sending; and so concentrate your whole attention on this one act of loving sight that all other objects are excluded from the consciousfield. Do not think, but as it were pour out your personality towards it: let your soul be in your eyes.Almost at once, this new method of perception will reveal unsuspected qualities in the external world.

What one seems to want in art, in experiencing it,

is the same thing that is necessary for its creation,

a self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration.

ELIZABETH BISHOP

First, you will perceive about you a strange and deepening quietness; a slowing down of our feverish mental time. Next, you will become aware of a heightened significance, an intensified existence in the thing at which you look. As you, with all your consciousness, lean out toward it, an answering current will meet yours. It seems as though the barrier between its life and your own, between subject and object, had melted away. You are merged with it, in an act of true communion: and you know the secret of its being deeply and unforgettably.

Many years later, photographer Minor White applied some of these principles of intimate perception and contemplation in his photography workshops in a process he called “creative audience.” In this book we will be dealing with the same process, embedded in the teachings of Zen and Zen meditation.

The inner—what is it?

if not intensified sky . . .

RAINER MARIA RILKE

It’s sometimes surprising what happens when we suspend judgment and get in touch with how art makes us feel. I sat in a creative feedback session once where two young women, Cynthia and Rose, were working on a photograph of a beautiful rocking chair sitting in front of a window, with light streaming on it. Rose, who was giving the feedback, began to describe how the chair made her think of an old woman with arthritis in one hand.

“She’s holding a cane,” Rose said, “and she’s wearing a shawl around her shoulders. She’s also a bit blind.”

While Rose was talking, Cynthia began to cry. Rose was describing Cynthia’s grandmother, an old woman who had sat in that rocking chair every day for forty years. Rose had never met Cynthia’s grandmother—she had passed away some time before—but her intuition allowed her to tap into the depths contained in the image of the rocking chair.

This is not an easy process. It requires a deep sense of trust between the person giving the feedback and the person receiving it, and it takes time and patience to develop this trust. Once the process is working, it acts as a doorway to insight. What we create in our lives can be a powerful teacher. A key element that enables this to happen is a creative feedback group. Members of such a group do not necessarily have to be artists. They can be peers, nonartists, anyone willing to look at your art.

In my own work, I have preferred to work with small groups. The group I used for years consisted of a couple of art critics, a photography teacher, an art student, a writer, the farmer across the road, and my mother.

It was very revealing to have such a mixed group since, even though their knowledge of and interest in art varied widely, the comments I heard from each were not that different. My mother, for example, never understood my abstract photographs. She would invariably say to me, “Oh John, you have such lovely children! Why don’t you photograph them instead of these silly rocks?” Yet, her feelings about my work were essentially identical to the feelings that the critics and photographers expressed.

Part of training a feedback group requires that you be relentless in demanding that your audience express their feelings, not their ideas, criticisms, or opinions. Some people have difficulty getting in touch with their feelings, but you’ll find that the process itself will help them to open up. It takes time, patience, and commitment to develop a functioning feedback group.

As the artist receiving the feedback, you need to train yourself how to hear what’s being said and draw out the information that only the audience can give you. The tendency for the artist is to “hear” what he wants to hear, according to his preconceived notions of his art, rather than what it is actually communicating.

One of the pitfalls of creative feedback is you may find yourself trying to create art that pleases your creative feedback group, rather than art that springs from your own vision. Learn from your group, but keep going, keep exploring. Don’t get hooked on looking for approval. It’s easy for us to work hard until we master a technique, then just keep plodding along in a rut because we know we can work well in it. Take chances. Some of the greatest work has been produced by people who were willing to be rejected. Experiment.

Practice: Creative Feedback

For creative feedback to work, we need to enter into the still point first, deepening our attention until the mind is relaxed, free of tension, and focused on the here and now. Although you may have been practicing zazen and have developed skill in attentiveness, your group of volunteers may not have acquired such skills. They will need to be guided through a relaxation and focusing process before engaging the art.

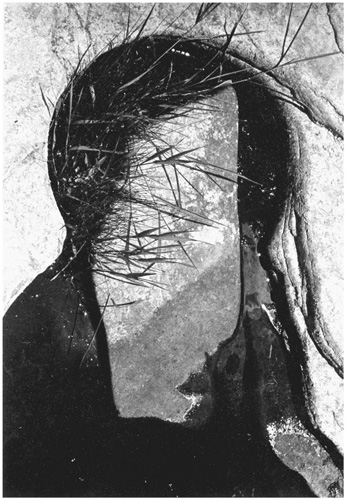

What follows is an example of how this process works. Using yourself as the audience and the picture on the previous page as the subject, try this practice yourself. Since creative feedback is a guided, meditative way of experiencing art, you should either prerecord the following instructions or have a friend read them to you as you engage the image. The instructions must be given in a slow and deliberate manner, allowing enough time for each step to be engaged.

Place the image in front of you, but don’t study it yet. Make yourself comfortable and relax your body completely. Begin by closing your eyes and becoming aware of your face, especially the muscles around the eyes. Become aware of any tension that may be there, then deliberately and consciously let go of that tension. Next relax the muscles of your jaw so it hangs loosely, gently pressing your tongue against the roof of your mouth. Now move to the muscles on the back of the neck; be aware of any tension there and let it go. Relax the muscles of the back, the shoulders, and the chest.

Become aware of your breathing. Allow yourself to breathe deeply and easily, without effort. Imagine each inhalation bringing energy into the body and each exhalation letting go of tension. If your mind begins to wander, don’t fight it. Witness what it’s doing, and after a few moments, bring your attention back to your breath.

Next let go of the tension in your stomach. Become aware of the muscles of the arms and let go of any tension that you may be holding. Do the same for the forearms, and the muscles in your hands. Feel the muscles of the thighs, the calves, and the feet, letting go of any tension left in your body.

Now imagine you are sitting next to a small pond. On its surface floats a white swan. It’s very still. There is no movement. No wind. No sound. Try to feel that stillness with your whole body. Try to contact that still place within yourself that relates to the pond and the swan.

Turn your awareness to your hara. Begin drawing energy from all parts of your body to that point, from the top of your head and the tips of your toes and fingers. Focus all the energy of your body in your hara; feel it building there. Now begin to move that energy upward to the back of your closed eyelids.

When you’re ready to begin, open your eyes, take a flash look at the image, and close your eyes again. Keep yourself still and quiet. How does it feel? What part of your body is involved in this perception?

Try to see the image on the back of your closed eyelids, and notice how you feel—not what you think of it, but how you feel. Fill in areas of the image that are unclear to you. Don’t worry about getting it right. Stay connected with your feelings.

Now open your eyes and take in the whole image at once. How does that feel? Not what you think of it, but how it feels. See everything that the artist intended to present. Begin to move slowly through the image. Are there parts that attract you more than others? Sections that repulse you? Allow your eyes to scan every section of the image— don’t leave anything out. Try to postpone your judgment. Just see and feel. If thoughts arise, acknowledge them, let them go, and return to just seeing, just feeling.

Now imagine yourself entering the image, becoming part of it. Be aware of how it feels from the inside. Are visceral sensations evoked by the image? Is it smooth, hot, pebbly? Do you feel nervous, excited, relaxed? Just keep seeing and feeling without judging or analyzing. Tune into your body as you move from area to area, noticing how the ground feels beneath your feet. Is it spongy, smooth, hard, wet? Are there any sounds? Smells? Don’t try to make sense of what you’re feeling. Just let it move through you.

Now choose a particular area of the image to go into. Become it. Notice how you feel, being this place. How does the rest of the image look from this position? Do you feel big, small, frightened, confident, weary, or angry? Notice any bodily sensations. How does it feel to move out of being this one area and back into the whole image?

What happens if you try to move out and beyond the image? How does the image continue beyond the borders? Do you feel relief, anxiety, fear, joy? Spend some time outside the borders of the image. Then return to the image just as it is, seeing it as a whole. Take it in all at once again, before closing your eyes, and again see the afterimage on the back of your closed eyelids. Fill in any areas that aren’t clear. Notice the sensations you are left with. Try to amplify the feeling and really experience it. Then let it go.

Draw your energy back down to your hara and away from your eyes. Feel the energy building there until you feel that sense of lightness, warmth, or buoyancy. Then consciously and deliberately let it go. Let go of the feeling; let go of the image. Become aware of yourself, the room, and sounds. Move your body slightly, and, when you’re ready, slowly open your eyes.

Now, if you’re in a creative feedback group with an artist whose work you’re responding to, you’re ready to give feedback. Stay with your feelings. Leave your analysis for a critical audience. Criticism is also important, but it’s a separate process. Try to convey to the artist everything that you experienced during the creative feedback process.

It’s easiest to learn the instructions for creative feedback using a visual medium, but once you are familiar with the process, you can adapt it to other art forms. For a short piece of writing, the “flash look”might be the word or two that catches your eye in that first impression. Then you can listen to or read the poem as a whole piece. Next, read the poem more thoroughly, line by line, allowing yourself to move into and experience each image or line, and how it feels to move through it. Then choose one phrase or line to move into and become that one phrase. Going beyond what is actually written on the page, do you feel you can move outside the poem? Does it continue in a similar way or radically change?

For a longer piece of writing, or a performance piece of dance or music, the “flash look”is simply your first impression, the change from the quiet before the piece begins to the initial movement. Stay aware of your visceral experience throughout. Allow yourself to be moved by the piece; move through it, in it. Allow yourself to become the music, words, or dance, noticing the sensations in your body. When the piece ends, close your eyes and sit quietly. Be aware of any residual impressions and feelings, and intensify them. Then consciously and deliberately let them go and return to your center and the sounds in the room. Then open your eyes.

The instructions for doing creative feedback with a visual image are presented in a way that will allow you to experience the image from different perspectives, not just what is comfortable or familiar to you. For other media, the same principles of awareness apply, but the process can’t be as structured. You need to open yourself to the movement of the piece as it is presented, allowing it to unfold without comments or criticism.

This kind of creative feedback requires a very deliberate commitment to stay with the direct experience, to not move away into day-dreaming, numbness, or inattention. Some parts of the piece may be difficult to feel, others pleasurable, but don’t try to prolong a particular feeling or hold yourself back.

It is also possible to give nonverbal feedback using touch, movement, theater, or mime. Be creative. The point is to communicate as clearly as possible your experience to the artist. One of the most powerful responses that I ever received came from a performance artist. His short performance directly transmitted his experience of my photograph. When he finished, I had no doubt about what my photograph communicated to him.

Please keep in mind that in this process, your art and audience are functioning as a teacher, a guru—a mirror reflecting you back to yourself.

If you still don’t understand.

Look at September, look at October.

Leaves of red and gold

Fill the valley stream.

JOHN DAIDO LOORI