EIGHT

The Zen Aesthetic

Up to this point we have been working with a series of ancient and modern practices and teachings that function in the arts of Zen. They inform and are reflected in a particular aesthetic unique to Zen. Over time, different art historians and commentators have attempted to define this aesthetic and its relationship to its roots in Zen Buddhism.

We have seen in working with zazen that as the meditation process deepens, a particular kind of chi or energy develops which ultimately leads to a state called samadhi, the falling away of body and mind. When this energy develops, absolute samadhi becomes working samadhi, which functions in activity. This is known as the functioning of “no mind,” one of the characteristics of the Zen aesthetic.

In no mind there is no intent. The activity, whatever it may be, is not forced or strained. The art just slips through the intellectual filters, without conscious effort and without planning. This functioning of no mind is sometimes called the action of no action. This is the Taoist concept of wu-wei: a continuous stream of spontaneity that emerges from the rhythm of circumstances.

There is a clear sense of the presence of this quality in Zen paintings and poetry. It is an essential component of the martial arts. In the instant in which there is intent there is expectation. Expectation is deadly because it disconnects us from reality. When we get ahead of ourselves, we leave the moment. No mind is living in the moment, without preoccupation or projection. On the other hand, hesitancy or deliberation will show in our art when we leave the moment. Words in a poem will not flow. Notes from the flute will lack smoothness. The flower arrangement will be contrived rather than a natural reflection of nature herself.

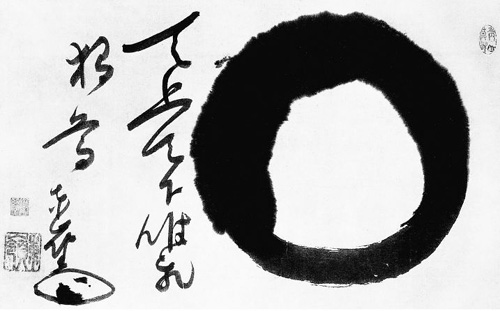

The Zen circle of enlightenment painted by the monk Torei Enji (1720–1792) embodies the quality of no mind. Torei was one of Hakuin’s chief disciples. His Zen circle is crude and closed, without the characteristic gap that Zen circles usually have. It is uneven, thick in some places, narrow in others, but bold and captivating. There is no sense that it is forced or strained. There is a feeling of emptiness and, simultaneously, of fullness and infinity. The poem included with the painting says, “In heaven and earth, I alone am the honored one.” These are the words attributed to the Buddha at the time of his birth. They are an expression of the realization of his unity with the totality of the universe, where there is no subject or object, no self, no other—where the moment fills all space and time. This is no mind.

This “no mind” approach to the creation of art ultimately led to a body of work that was devoid of the usual characteristics found in sacred arts, such as perfection, grace, formality, or holiness. The sacred arts of Zen do not aspire to these ideals, but are instead imperfect and worldly. It is through their ordinariness that they go beyond perfection and holiness.

The great Zen master Linji said, “Followers of the way, if you want to get the kind of understanding that accords with the teachings, never be misled by others. Whether you are facing inward or facing outward, whatever you meet up with, just kill it. If you meet a buddha, kill the buddha.”

The word “kill” here is not literal. It means to put an end to, or to cause to stop. That is, not to be controlled by convention, precedent, or rules, but to express one’s creative energy freely and spontaneously.

When seen in paintings, this quality appears as irregularity, crookedness, unevenness, or it may be seen as the shocking or unusual turning of a phrase in a poem. Sometimes called “the rule of no rule,” this characteristic reflects a fundamental aspect of Zen teachings which is called “teaching outside of patterns” or “action outside of patterns.”

Zen teaching and practice tends to be expressed very directly, without excessive ornamentation. The design of a typical Zen monastery reflects this. The space is sparse, unobtrusive, and uncluttered. We see this in the simple flower arrangement on the Buddhist altar, in the architecture of the monastery’s buildings, in its gardens and pathways. We also see it in the kind of food that is served and the way it is served, as well as in the practitioners’ vestments. All of it reflects a simplicity that allows our attention to be drawn to that which is essential, stripping away the extra.

We hear this simplicity in the chanting during liturgy. Chants are monochromatic and follow the deep drone of a wooden drum. They tend to ground us, rather than lift us to higher states of consciousness, the way that Gregorian chants might do. The chanting has the sound of a heartbeat or the pounding of the surf.

This quality of simplicity or lack of complexity opens up a creative space that is filled with possibility. In simplicity there is a touch of boundlessness. Nothing limiting, like a cloudless sky. There is a dynamic that exists in the relationship of form to space, or of sound to silence. The moment the brush touches the blank canvas, the empty space springs into activity and enters a dynamic relationship with form. When the wooden block is struck to call practitioners to the meditation hall, the sounds are interspersed with silence of decreasing length.

This quality of simplicity is also experienced in the execution of a work of art. Calligraphy is often produced in a single stroke. Some zenga paintings are created, and haiku is recited, in a single breath:

Garden butterfly—

a child crawls to it; it flies.

He crawls; it flies.

ISSA

Our lifestyles have become extremely complex. How can we simplify our lives, reduce consumption, lower our impact on the environment, do less harm to other living things, reduce expenses, have fewer distractions, have less maintenance, enjoy more freedom and flexibility, and be able to live in a way that is financially less demanding? These are the questions that the simplicity of Zen can help to address.

Another trait of the Zen aesthetic is “no rank.” Master Linji, instructing his assembly, said, “In your lump of red flesh is a true person without rank who is always going in and out of your senses. Those who have not yet realized this should look! Look!”

The true person of no rank cannot be measured or gauged. There is a sense of being matured, seasoned, or ripe. Inexperience and immaturity have vanished. In their place appears a hardiness that comes with aging.

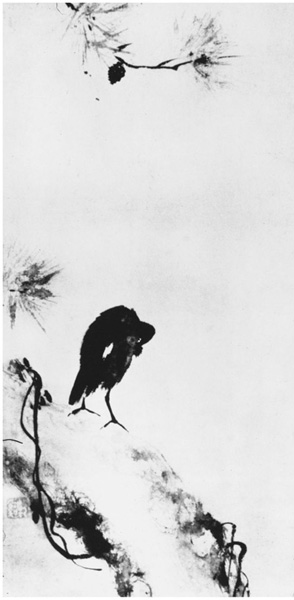

This quality is regarded as an important element in the Zen concept of beauty, which first emerged in the Heian period when the Japanese aesthetic of poetry was being defined. No rank, or ordinariness, reflects a seasoning wherein all weakness and frailty have been removed. Sensuousness disappears and in its place surfaces a poverty in which there is nothing superfluous. The late thirteenth-century Chinese painter Muchi’s bird on an old pine is a manifestation of the quality of mystery in the Zen aesthetic. With a few bold brushstrokes, Muchi has created a timeless image. The crow is clearly the nucleus of the painting. The surrounding space gives the image openness and freedom. It clearly conveys a sense of containing within itself the totality of being. The tiny dot of the crow’s eye pulls you into the painting’s boundlessness.

Deep in this mountain

is an old pond.

Deep or shallow,

its bottom has never been seen.

JOHN DAIDO LOORI

Whether we’re speaking of art, religion, or life, there are always apparent edges beyond which we cannot see. As Master Dogen says, the limits of the knowable are unknowable. The process remains open. There is an element of trust that must be functioning, a trust that when the foot is thrust forward to take the next step, it will find solid ground. There is always a little bit further than can be seen.

In the Zen arts, this is reflected as implication rather than naked exposure of the whole. From within that sense of bottomlessness is born a sense of possibility and discovery. That is the way life is. That is the way truth is. It cannot be contained. It extends indefinitely and infinitely. New perspectives previously unseen appear and open up. Where does it end? It’s endless. It is without boundaries. That’s what makes the unknowable so wonderful and pregnant with possibilities.

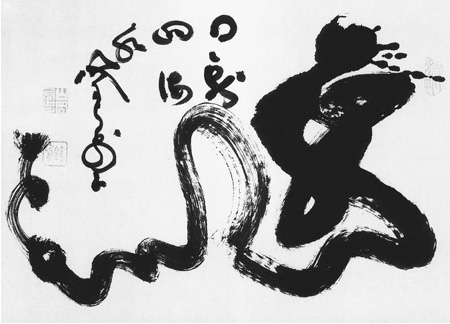

Yamaoka Tesshu’s (1836–1888) dragon is an embodiment of this quality. The dragon is a mysterious enlightened being in Zen lore. Tesshu’s poem accompanying the calligraphy reads: “Dragon—it feasts on sunlight and the four seas.”

Despite its obvious profundity, the Zen aesthetic also contains a certain playfulness in the way the teachings are presented, perceived, and transmitted. Zen embodies a wide and unusual range of teaching methods, unique religious expressions, and a healthy ladleful of laughter, humor, clowning, and playfulness. Zen has always taken the liberty of poking fun at itself and dispelling the legend of grim austerity that people sometimes conjure up when they think of Zen because of the intensive meditation that accompanies it.

By faithful study of the nobler arts, our nature’s

softened, and more gentle grows.

OVI D

In the paintings of Zen we see again and again the monk Hotei, who traveled about carrying a bag of things discarded by people to give as gifts to the children he encountered along the way. He is often portrayed laughing at falling leaves and delighting in all things. During his life, people weren’t sure whether he was a sage or a madman.

Master Nanquan said to Master Huangbo, “Elder, your physical size is not large, but isn’t your straw hat too small?” Huangbo said, “Although that’s true, still, the entire universe is within it.”

ANDREW FERGUSON, TRANS., ZEN ’ S CHINESE HERITAGE

The characteristics we have been dealing with up to this point are essentially palpable qualities. Still point, no mind, simplicity, ordinariness, mystery, playfulness are traits that can be seen in a picture, heard in a poem, or perceived in a subject. There is, however, one other aspect of the Zen arts that is less obvious. We must rely on our intuitive faculties to become aware of it. It is suchness.

Suchness, or thusness, is used in Zen literature to suggest the ineffable: a truth, reality, or experience that is impossible to express in words. It refers to the “that,” “what,” or “it” that is self-evident and does not need explanation. It is essentially being as it is, the all-inclusive reality that is manifested as a sense of presence.

Everything should be as simple as it is,

but not simpler.

ALBERT EINSTEIN

When Yantou came to Deshan, he straddled the threshold

And asked, “Is this common or holy?”

Deshan immediately shouted.

Yantou bowed low.

BOOK OF EQUANIMITY, CASE 22, INTERNAL TRANSLATION

Thusness is the points of two arrows meeting in midair. It is a quality of being that is nondual and does not fall into either side.

Once a monastic bid farewell to Zhaozhou. Zhaozhou said,

“Where are you going?”

The monastic said, “I will visit various places to study the

teachings.”

Zhaozhou held up the whisk and said, “Do not abide in the place where there is a buddha. Pass by quickly the place where there is no buddha. Upon meeting someone three thousand miles away, do not misguide that person.” EIHEI DOGEN ’ S THREE HUNDRED KOAN SHOBOGENZO, CASE 80, JOHN DAIDO LOORI AND KAZUSKI TANAHASHI, TRANS.

This holding up of the whisk points to the meeting place where differences merge.

The quality of suchness is not limited to this nondual instant of merging alone. There is more to it than that. Zen Master Yuanwu addressed the assembly, “If you want to attain the matter of suchness, you must be a person of suchness. Since you already are a person of suchness, why raise concern about the matter of suchness?”

In the words of Zen Master Dogen, “Because [the truth] is suchness, it is something that arouses the Bodhi mind spontaneously. Once this mind arises, we throw away what we played with before and we vow to hear what has not yet been heard, and we seek to verify what has not yet been verified. It is not at all our own doing.”

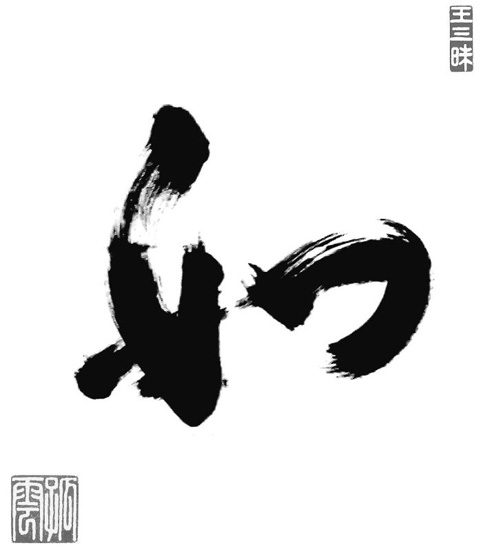

Suchness is not something added from outside. It is being itself. It is in living life itself. It is the “isness” of a thing, indeed, the isness of existence itself. Suchness is a translation of the Sanskrit word tatha, sometimes used as part of the term used to refer to the Buddha: Tathagata, the “One Who Thus Comes.” It is expressed in the calligraphy Thus! of Maezumi Roshi. It can be felt in Muchi’s “Persimmons,” six simple fruits, no two alike, suspended in space, and with an irrefutable sense of presence: Here we are!

To bring that sense of thusness into a painting, poem, or piece of music gives it a vitality that is easily experienced, although difficult to pinpoint. It may be only an instant in time, a moment out of the constant flow of life. But to sense thusness and to be able to express it brings it into our own reality.

Dirt on the cool melon

muddied

by the morning dew.

BASHO

Several hundred years later, Joyce Carol Oates expressed thusness with a similar subject in her poem “That”:

A single pear in its ripeness this morning swollen ripe,

its texture rough rouged,

more demanding upon the eye than the tree

branching about it.

More demanding than the ornate grouping limbs

of a hundred perfect trees.

Yet flawed, marked as with a fingernail,

a bird’s jabbing beak, the bruise of rot,

benign as a birth mark, a family blemish.

Still, its solitary stubborn weight, is a bugle,

a summoning of brass.

The pride of it subdues the orchard.

More astonishing than acres of trees, the army of ladders,

the worker’s stray shouts.

That first pear’s weight exceeds the season’s tonnage,

costly beyond estimation,

a prize, a riddle, a feast.

As we begin to realize how to recognize suchness and move with it, rather than opposing it, we enter a realm of harmony with the flow of things and we’re able to discover for ourselves the words of Master Jianzhi Sengcan:

Obey the nature of things [your own nature]

and you will walk freely and undisturbed.

When thought is in bondage, the truth is hidden,

for everything is murky and unclear,

and the burdensome practice of judging

brings annoyance and weariness.

What benefit can be derived

from distinctions and separations? . . .

. . . For the unified mind in accord with the Way

all self-centered striving ceases.

Doubts and irresolutions vanish

and life in true faith is possible.

With a single stroke we are free from bondage;

nothing clings to us and we hold to nothing.

All is empty, clear, self-illuminating,

with no exertion of the mind’s power.

Here thought, feeling, knowledge and imagination

are of no value.

In this world of Suchness,

there is neither self nor other-than-self.

In an attempt to deepen our appreciation of some of the characteristics we have discussed in this chapter, I would like to show how they function within some of the various Zen arts, so that we may gain insight into how they might appear in contemporary art and life.