NINE

Have a Cup of Tea

Zhaozhou questioned two new arrivals at his temple. He asked the first monk, “Have you been here before?” The monk said, “No, I haven’t.” Zhaozhou said, “Have a cup of tea.” Then he asked the second monk, “Have you been here before?” The monk said, “Yes, I have.” Zhaozhou said, “Have a cup of tea.” The head monk asked,“Setting aside the fact that you told the one who’d never been here before to have a cup of tea, why did you tell the one who had been here before the same thing?” Zhaozhou said, “Head monk!” The head monk responded, “Yes?” Zhaozhou said, “Have a cup of tea.”

EIHEI DOGEN, THREE HUNDRED

KOAN SHOBOGENZO, CASE 233

Tea is to East Asian Buddhism what wine is to the Judeo-Christian traditions. It holds a sacred place.

Chado, the way of tea, has been called the expression of Buddhism’s spiritual, philosophical, moral, artistic, and social aspects. It embodies the spirit of the artless arts of Zen and contains all the essential characteristics that define the Zen aesthetic. Many of the other Zen arts—calligraphy, poetry, flower arrangement, and gardening—are also prominently featured in the context of the tea ceremony.

Although I’ve experienced the formal tea ceremony many times and in a variety of circumstances, my first encounter with it in a traditional teahouse at a small temple in Japan was a memorable occasion.

The path to the teahouse was a winding trail of stepping-stones that guided us through the tea garden. The slow approach made my companion and me appreciate the mountain setting and gently disconnected us from the urban turmoil we were leaving behind. The garden was simple, yet beautiful. Little clusters of moss on stone and a meandering stream that disappeared behind the teahouse embodied serenity and a timeless beauty.

The teahouse itself was surprising in its simplicity, contrasting with the more elaborate buildings of the temple compound. It was a small hut, like a hermitage for a single person. It had a thatched roof and was constructed with rustic materials. The natural tones matched its setting. We approached a low stone basin into which water flowed through a bamboo pipe. We stopped to rinse our hands and mouths in a symbolic act of purification—a preparation for the ceremony.

The entryway to the hut was a four-foot-high sliding door. In order to come in, we had to lower ourselves nearly to the ground. Once inside, the first thing we encountered was the tokonoma, a small alcove that held a single scroll of calligraphy with a poem that was appropriate to the season. There was also a modest flower arrangement, the blossoms reflecting the spring months. The light, filtering through shoji screens, was subdued. The room had a soft glow to it, and the walls were bathed in gentle, warm colors. As my tea partner and I took our places, settling ourselves comfortably on the tatami mats, we could hear the sound of boiling water in a cast iron kettle and birdsong outside.

The great earth innocently

nurtures the flowers of spring.

Birds trust freely

the strength of the wind.

All this derives from the power of giving,

as does our self, coming into being.

JOHN DAIDO LOOR I

Usually, conversation in a teahouse avoids business matters or controversial subjects such as politics. It focuses rather on nature and the unfolding season, or relaxed silence is maintained. In this case, we chose to simply remain silent and absorb the atmosphere.

The tea master appeared. Kneeling, he placed his fan in front of him and lowered his head to the ground, welcoming us. We returned his bow. He exited the room and began to bring in the implements for the ceremony. Holding one corner of a silk cloth in his left hand, he ran his right hand down the cloth and smoothly folded the cloth into three parts. Reaching the end of the cloth, he joined the corners together, folding the cloth again in three parts. He then used this piece of silk to symbolically clean each of the ceremonial objects—symbolically, because the tea implements were already meticulously clean. He ritualistically rinsed the bowls with hot water taken from the kettle as we watched. He dipped a bamboo whisk in the water, examined it, and placed it to one side. He poured the hot water into the tea bowl, and then wiped the bowl with a damp cloth.

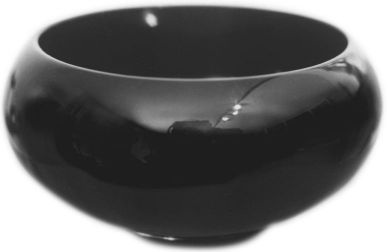

The master gestured to us, inviting us to enjoy the sweets that he had placed before us. While we ate, he proceeded to prepare the tea. With deft movements he opened the tea caddy and with a bent bamboo spoon measured jade green powdered tea into the bowl. He dipped a long-handled dipper into the kettle and poured hot water onto the tea. Then, with a bamboo whisk, he whisked the tea into a froth. He turned and set a bowl in front of me, with the most striking side of the bowl deliberately facing toward me. I lifted the bowl and brought it closer. I bowed to my tea partner. I lifted the bowl into the palm of my hand and turned it two short turns so its “front” faced away from me. I bowed to the tea and drank it in a few sips, slurping the last bit, which is considered in good taste in Japan.

Finishing the tea, I rotated the bowl to its original position and placed it on the floor in front of me. I bowed. The tea master retrieved the bowl and washed it with hot water. Meanwhile, my companion enjoyed his tea. After he was finished and the master had cleaned his bowl, the master returned the bowls to us so we could examine them and appreciate their uniqueness.

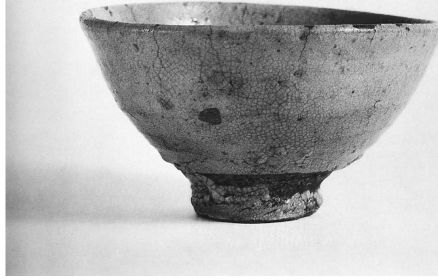

Historically, many of the most sought-after bowls for tea ceremony in Japan were dull colored and roughly finished, not elegant or refined in their craftsmanship. A few of the favored tea bowls were originally inexpensive but wonderful Korean rice bowls intended for everyday use. They were accidental masterpieces of form and design—asymmetrical, cracked, occasionally wobbly, with a thick coating of glaze and an unglazed foot.

The appreciation of the utensils and bowls we used was an important part of the ceremony. Each of them was picked especially for us, brought out for the occasion by our host. We leisurely examined the bowls and the utensils, appreciating their finer qualities, and then returned them to the tea master. He put them away in a little alcove and returned to kneel in front of us. The ceremony concluded the way it began. He placed his fan on the ground in front of him and lowered his head to the floor. We returned the bow, and he retired to the alcove. We left the way we came, down the winding path through the garden, back into the fray of our lives, yet somehow more buoyant, more fulfilled than when we had entered the teahouse.

I realized that the tea ceremony was a manifestation of the merging of host and guest, the apparent differences that are spoken of in the teachings of Zen, as well as a beautiful reflection of the liturgy I had experienced in Zen monasteries.

A well-performed tea ceremony will provide the participants with the taste of certain qualities of the artless arts. To the eye of an experienced tea master, the tea bowls display wabi and sabi, qualities that have become synonymous with the Zen aesthetic. Wabi is a feeling of loneliness or solitude, reflecting a sense of nonattachment and appreciation for the spontaneous unfolding of circumstances. It is like the quiet that comes from a winter snowfall, where all the sounds are hushed and stillness envelops everything. Sabi is the suchness of ordinary objects, the basic, unmistakable uniqueness of a thing in and of itself.

Two other qualities used to describe the feelings that Zen art evokes are aware and yugen. Aware is a feeling of nostalgia, a longing for the past, for something old and worn. It’s an acute awareness of the fleeting nature of life, its impermanence. Yugen is the mystery, the hidden, indescribable, or ineffable dimensions of reality. These qualities are expressed by the bowls, the hut, the master’s movements. They are in the atmosphere itself. This is the classic expression of the Zen aesthetic, which can be found not only in the arts of Zen, but throughout Japanese culture as well.

If only you could hear

the sound of snow . . .

HAKUIN EKAKU

There is also the overarching theme of poverty in chado—not the poverty of down and out, but of bare-bones simplicity, the simplicity of not clinging to anything.

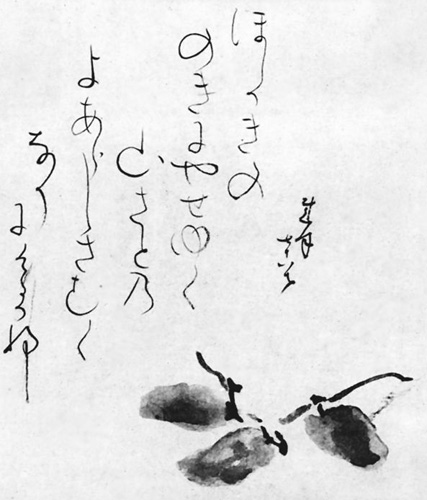

Ryokan, a Zen master and poet, lived in a simple thatched hut. He was born around 1758 and ordained at the age of eighteen. Shortly after receiving dharma transmission, Ryokan’s teacher died. The poet went to live in a hermitage on Mount Kugami, where he spent his time sitting zazen, talking to visitors, and writing poetry. Many stories of Ryokan’s simplicity and his love for children have come down to us, as well as of his indifference for worldly honor. In fact, Ryokan called himself Daigo (Great Fool).

One evening, when Ryokan returned to his hut, he surprised a thief who was naively trying to rob the hermit. There was nothing to steal in the hut. Yet Ryokan, feeling sorry for him, gave him his clothes, and the thief, shocked, ran away as fast as he could. Ryokan, shivering as he sat naked by the window, wrote the following haiku:

The burglar

neglected to take

the window’s moon.

To be simple means to make a choice about what’s important, and to let go of all the rest. When we are able to do this, our vision expands, our heads clear, and we can better see the details of our lives in all their incredible wonder and beauty.

Simplicity does not come easily to us in the West. In general, we don’t like to give anything up. We tend to accumulate things, thinking that if something is good, we should have more of it. We go through life hoarding objects, people, credentials, ignoring the fact that the more things we have to take care of, the more burdensome our lives become. Our challenge is to find ways to simplify our lives.

Rikyu, the founder of the tea ceremony, was a serious student of Zen. He spent many years in rigorous training in the monasteries of Japan. After perfecting the ritual aspects of the tea ceremony, he became widely known and respected. Rikyu’s close friend, the shogun, regularly frequented Rikyu’s teahouse. The shogun, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, though known to be a despot, was also a great patron of the tea ceremony. In praise of Rikyu he recited the following poem at one of his tea parties:

When tea is made with water drawn from the depths of

Mind

We really have what is called chado.

One summer, Rikyu managed to acquire blue morning glory seeds, virtually unknown in Japan at the time. He planted them in the garden around his tea hut. This was discussed widely, and eventually word of the morning glories reached the shogun. He sent his messenger to tell the tea master that he would come for tea in order to see the new flowers. A couple of days later, the shogun appeared at Rikyu’s place, but when he strolled into the garden, he couldn’t find a single morning glory.

“Where are those beautiful new flowers I’ve been hearing so much about?” asked the shogun.

“I had them removed,” answered Rikyu.

“Removed!” said the shogun, surprised and not a little perturbed. “Why?”

“Come,” said Rikyu, leading the shogun to the teahouse. The shogun angrily removed his swords and shoes and then bowed down to enter through the low door of the tea room. In the tokonoma, resting in a slim bronze vase, lay a single, freshly cut morning glory, still wet with the morning dew. At that instant, without any distractions standing in the way, the shogun saw that flower, singular in its beauty, completely filling his universe.

All beings are flowers

Blooming

In a blooming universe.

SOEN NAKAGAWA

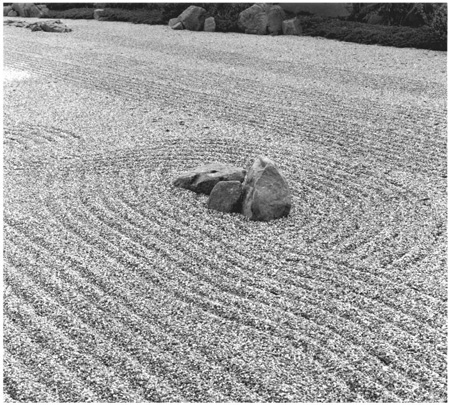

The quality of simplicity that is present in traditional Zen monasteries also exists in Zen gardens. A Zen garden features a few carefully placed rocks, raked sand, and trees trimmed to expose the hills in the distance. Each rock is chosen because of its characteristic shape and form. In the West, by contrast, our gardens tend to overflow with beauty, so much of it that we miss the beauty.

Our culture of excess is growing, infiltrating even our most basic activities. Overeating and obesity are epidemic in the United States. The size of servings at restaurants has doubled in the past twenty years. In Japanese restaurants a small steak comes on a very large plate with a little cluster of potatoes, a few spears of vegetables, and a sprig of parsley. The portion is reasonable in size and appealing in its presentation, with the same dynamic of form and space seen in a Zen garden. We are nourished by the presentation as we are nourished by the food. And we walk away a little hungry. My dharma grandfather Yasutani Roshi used to say, “You should always stop eating before you feel completely full.” That’s one of the themes in oryoki, the ceremonial meal taken at Zen monasteries during long meditation intensives.

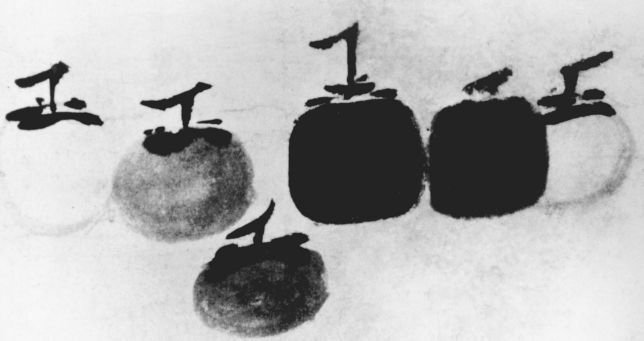

In developing the tea ceremony, Rikyu was influenced by oryoki or juhatsu, the liturgy of eating practiced respectively in the Soto and Linji schools of Zen. Oryoki roughly means “that which contains just enough,” and it also refers to the Buddha bowl monks receive at their ordination. Oryoki, like the tea ceremony, is a very detailed ritual. Each movement is attended to with care and painstaking detail. Everyone begins and finishes together. Starting with the five bowls that are lined up over a folded cloth, to the serving and receiving of the food, to the cleaning and wrapping of the bowls, each movement in oryoki is precise and deliberate. Chants accompany the ceremony, which emphasizes that what is taking place is not only the ordinary act of eating, but a sacred activity.

In Zen monasteries, the beginning and end of each activity is punctuated with appropriate liturgy. This ranges from a simple gesture of placing both hands palm-to-palm together in gassho and bowing before entering a room, to an elaborate, two-hour-long funeral service. This mindful engagement of an activity is designed to help us awaken to what we are about to do. Formal ceremonies, work and study, the practical functions of eating and washing are all carried out with a mind that is alert, attentive, and completely present. When the mind is in that state, every single thing we encounter is as complete and simple as Rikyu’s morning glory.

It is easy to imagine that the formality of the tea ceremony or oryoki is confining, or that the spirit of simplicity calls for everything to be stripped away, leaving only a bare form. Nothing could be further from the truth. When completely embodied, the true spirit of simplicity is freedom in action. Within the specific form we become free of that form.

Once, Soen Roshi and a group of students were meeting someone at Kennedy Airport in New York City. One of the students arrived late. When he appeared, Soen said to him, “You missed the tea ceremony.”

“A tea ceremony at Kennedy Airport?” said my friend, looking around him incredulously. “Where?”

“Ah,” mused Soen. “Maybe you’re not too late. Come with me.” Soen dragged him into a nearby doorway. Two women rushed by pulling huge suitcases behind them, while a man waved frantically at someone in the distance. They didn’t notice a strange Japanese man in flowing robes with his arm around his bewildered companion.

Soen reached into his sleeve and pulled out a little porcelain container with powdered green tea and a small bamboo spoon. He took a spoonful of tea and said, “Open your mouth.” My friend obeyed and Soen plopped the tea in his mouth, lifted his chin so his jaw was closed, and said, “Now, make water.”

The elaborate ritual of the classic tea ceremony, which can take over an hour, was reduced to its essence in this simple act. All that was left was the taste of tea.

The fact that both of these manifestations of tea ceremony— Soen’s improvisational form and the traditional and elaborate ritual—can exist side by side is a testimony to the true spirit of freedom implicit in the teachings and practice of the Zen arts.

Ultimately, oryoki, like the tea ceremony, is a state of mind. It has nothing to do with a set of bowls or being in a meditation hall. It has everything to do with being completely present, and doing what we’re doing while we’re doing it—whether we’re at a Burger King, an airport, or a monastery. If our mind is cluttered with thoughts or worries, we’re not doing oryoki. We’re not being simply present. The way we use our mind is the way we live our lives. If we understand these principles and take them up as practice, we will liberate ourselves.

There was an old tea master who received notice that a high official would be coming to have tea at his teahouse. He directed his young apprentice to prepare the garden for the guest. The apprentice worked diligently all morning, raking and clearing the garden of fallen leaves that had cluttered the streams and the rock gardens. He persisted until the garden was meticulously clean, not a stray leaf in sight. When he asked the tea master to examine his work, the master looked at it and said, “Almost perfect, but not quite.” Then he walked over to a couple of the maple trees and shook them lightly so a few crimson leaves fell on the path and garden.

For simplicity to be simple, it needs to be natural, almost unnoticeable. It can’t be contrived or forced. The meticulous garden calls attention to itself by virtue of its meticulousness. Going a bit further with this story, I would say, let the leaves just fall on the path by themselves.

Layman Pang, a ninth-century Chinese Zen master, had his own version of simplicity. Realizing that he wanted to devote the rest of his life to the spiritual path, Pang loaded all of his possessions onto a boat and sunk them in a river. I’ve always wondered why he didn’t give his stuff away to people who could have used it. His intent was noble, but he went a bit overboard.

Being simple doesn’t mean being simpleminded. It doesn’t mean indiscriminately getting rid of everything you don’t want, or doing away with form, style, or discipline. Nor is it the other extreme: enduring the discomforts of simplification, putting yourself through a heroic cleansing, a forced renunciation or asceticism.

Renunciation is not giving up the things of this

world, but accepting that they go away.

SHUNRYU SUZUKI

Many years ago I set off on a weeklong canoe trip in the headwaters of the Oswegatchie River in upstate New York. Arthur, a Jamaican friend, who had spent most of his life hunting, fishing, and backpacking, generously offered to accompany me. I loved the outdoors, but had never spent an extended period of time cross-country camping.

Arthur arrived at Cranberry Lake village, where we had agreed to meet, just as I was cramming the last of my gear into the pack. My canoe, Chestnut Darling, was on the ground next to the car. Arthur took one look at my pack and burst out laughing. “Man, you got the white man syndrome!” he said, shaking his head. I stared at him blankly. “What are you trying to do—bring your entire house with all of its comforts into the woods?”

I looked at my pack. Every single compartment, down to the tiniest pocket, was filled with various items. I thought all of them were necessary. It didn’t take me long to find out that trying to carry a ninety-five-pound pack across long canoe portages was not only uncomfortable, but unnecessary. I couldn’t keep up with Arthur. Still shaking his head and grinning, he switched packs with me, and carried my “house” for the rest of the trip. To his credit, he agreed to go out with me again. Next time around we trimmed my pack down to sixty-five pounds.

As time went by, my love of camping grew, and my packing ability improved. First, I did away with the extras, the little amenities that were really not necessary to survive, like books. Then I stopped taking pots and silverware. I cooked food in my army surplus canteen cup and ate with my sheath knife. Seeing how much I could pare down became both a challenge and an obsession. I did away with all my extra clothes, and learned to pack just enough food to last me the length of the trip. With each successive outing, my pack got leaner and leaner, and I realized I did not miss the equipment at all. On the contrary, I felt lighter, freer, and more in touch with my surroundings than I had before.

My wife did not share my enthusiasm for minimalist camping, and since I was adamant about not bringing anything on our trips that wasn’t absolutely necessary, she began to smuggle silverware and books by taping them to her body.

One late summer in 1965 I returned to the headwaters of the Oswegatchie, this time by myself. I set up camp in the early evening and the next morning packed my camera and a knapsack with a small survival kit, intending to spend the day photographing a distant mountain lake I had spotted on my map. The day was cool and overcast, the light perfect for photographing. I hiked a couple of miles to a small swamp, waded slowly through it, and continued. I made my way up the mountains until I reached the lake. It was a small but beautiful expanse of water, its slate-gray surface rippling softly in the wind.

I shot through the changing light, but before long it started to rain and I had to pack my gear. The rain turned into a downpour. I thought I could wait it out, but after a couple of hours it still hadn’t let up. I decided that the best thing would be to return to my camp-site. I made my way down the mountain, through the woods, and back to the swamp, only to discover that the rain had turned it into a pond that was too deep to cross. I tried to find my way around it, but couldn’t. Night was falling, it was turning cold, and the storm continued in full force. I didn’t think I would be able to retrace my path in the dark, so I decided to stay where I was until morning.

I felt both apprehensive and excited as I searched for high ground, far from the water in case it continued to rise. Here was a real test of my ability to make do without gear. I began by creating a small circle of rocks in front of a large boulder that would reflect the heat of a fire. I rigged my poncho into a lean-to, then built a small fire and made a cup of broth from a packet that I always carried in my survival kit. Tired, and warm from the soup, I settled down with my back against a tree.

Arm for a pillow, watching the gemlike

raindrops from the eaves, alone.

BASHO

When I awoke in the middle of the night, the storm was still sweeping over the mountains, but I was perfectly warm and dry. I threw more wood on the fire, watching the storm. I slept on and off until morning, and in the light of day it was easy to bushwhack my way around the pond and pick up the trail that led back to my camp.

That trip completely changed the way I perceived camping. I realized that with a bit more food, I could have stayed out for several days. Even the minimal pack that I was so proud of had proved unnecessary. These days, I camp with a tent, a stove, and silverware again, but I haven’t lost the spirit of simplicity I touched in those early trips.

The Zen arts in their bare-bone simplicity and sobriety may sometimes appear archaic, but they are surprisingly modern, both in appearance and function. The lines of a classic Japanese teahouse, rock garden, or a simple ceramic pot are invariably clean and elegant. By avoiding overstatement, the Zen artist conveys the impression of disciplined restraint, of having held something in reserve. And in the art’s empty spaces we sense a hidden plenitude. The result is a feeling of implied strength, a suspicion that we have only glimpsed the power and full potential of the artist.

In a society that assures us that more is better, it’s not always easy to trust that we have enough, that we are enough. We have to cut through the illusion that abundance is security, and trust that we don’t have to buffer ourselves against reality. If we have learned to trust abundance, we can learn to trust simplicity. We can practice simplicity.

Zen, and by extension the Zen aesthetic, shows us that all things are perfect and complete, just as they are. Nothing is lacking. In trying to realize our true nature, we rub against the same paradox: We don’t know that we already are what we are trying to become. In Zen, we say that each one of us is already a buddha, a thoroughly enlightened being. It’s the same with art. Each one of us is already an artist, whether we realize it or not. In fact, it doesn’t matter whether we realize it—this truth of perfection is still there. Engaging the creative process is a way of getting in touch with this truth, and to let it function in all areas of our lives.

No creature ever comes short of its own completeness.

Wherever it stands, it does not fail

to cover the ground.

EIHEI DOGEN

If I was asked to get rid of the Zen aesthetic and just keep one quality necessary to create art, I would say it’s trust. When you learn to trust yourself implicitly, you no longer need to prove something through your art. You simply allow it to come out, to be as it is. This is when creating art becomes effortless. It happens just as you grow your hair. It grows.