FOURTEEN

Indra’s Net

Imagine, if you will, a universe in which all things have a mutual identity. They all have an interdependent origination: When one thing arises, all things arise simultaneously. And everything has a mutual causality: What happens to one thing happens to the entire universe.

Imagine a universe that is a self-creating, self-maintaining, and self-defining organism—a universe in which all its parts and the totality are a single entity, all of the pieces and the whole thing are, at once, one thing.

This description of reality is not a holistic hypothesis or an all-encompassing idealistic dream. It is your life and my life. The life of the mountain and the life of the river. The life of a blade of grass, a spiderweb, the Brooklyn Bridge. These things are not related to each other. They’re not part of the same thing. They’re not similar. Rather, they are identical to each other in every respect.

Lest we assume that this is simply some esoteric Buddhist metaphysics, consider the recent quantum physics experiment conducted in Geneva, Switzerland. The researchers took a pair of photons and sent them along optical fibers in opposite directions to sensors in two villages north and south of Geneva. Reaching the ends of the fibers, the photons were forced to make a random choice between alternative and equally possible pathways. Since it is expected that there is no way for the photons to communicate with each other, classical physics predicted that one photon’s choice of a path would have no relationship or effect on the other photon’s choice. But when the results were studied, the independent decisions by the pairs of photons always matched and complemented each other exactly, even though there was no physical way for them to relay information back and forth. If there was communication, it would have had to exceed the speed of light, which, according to Einstein, is not possible.

There is no place at all that is not looking at you.

RAINER MARIA RILKE

Each photon knew what was happening to its distant twin and mirrored the twin’s response. This took place in less than one one-thousandth of the time a light beam would have needed to carry the news from one place to the other. The connection and correlation between the two particles were instantaneous. They were behaving as if they were one reality. This experiment indicates that long-range connections exist between quantum events, and that these connections do not rely on any physical media. The connections are immediate and reach from one end of the universe to the other. Spatial distance does not interfere or diminish the connectedness of the events.

This interconnectedness of all things revealed in the Geneva experiment has been part of the Zen teachings for 1,500 years. It’s spoken of as the diamond net of Indra, in which all things are interconnected, co-arising, sharing mutual causality. Every connection in this net is a diamond with many facets, and each diamond reflects every other diamond in the net. In effect, this means that each diamond contains every other diamond. You cannot move one diamond without affecting all the others. And the whole net extends throughout all space and time.

Only the incomprehensible gives any light.

SAU L BELLOW

This diamond net is not a metaphor. For Zen Buddhists, it is an accurate description of reality. It is a description of what is realized in the practice of Zen. That is, the fact that we are all totally, completely, and intricately interconnected throughout time and space.

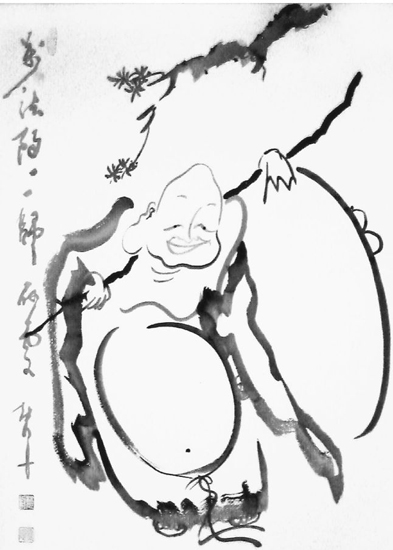

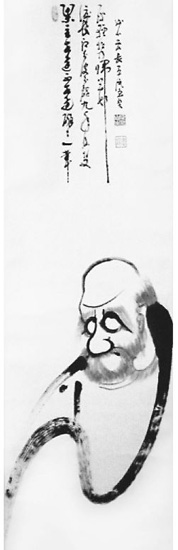

This same truth was expressed by the Indian monk Bodhidharma. As I mentioned before, Bodhidharma defined Zen as “a special transmission outside the scriptures, with no reliance on words and letters. A direct pointing to the human mind and the realization of enlightenment.”

One of the immediate misconceptions about this statement is to devalue words or imagine that by remaining mute we arrive at enlightenment, that ideas have no value in realizing the truth of the universe. There are Zen monasteries and centers where reading is strictly forbidden and books are kept under lock and key.

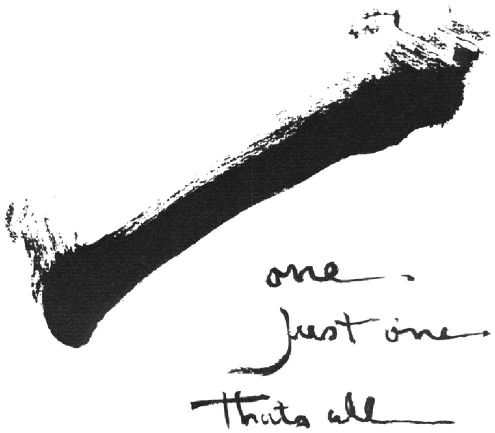

Because of Bodhidharma’s declaration, there evolved in Zen lore the phrase, “Painted cakes do not satisfy hunger.” This is an echo of “Zen does not rely on words and letters.” That is, painted cakes—a representation of reality, the words, ideas, images that describe a reality—are not the reality itself. And they do not satisfy our hunger for reality.

This is a narrow interpretation of Bodhidharma’s phrase. Zen master Dogen corrected this misunderstanding. He was not only open to using language as a way of teaching the truth of reality, but also clearly recognized that the symbol—the word or image—and the symbolized are in actual fact a single reality. Dogen took up “painted cakes” and made them nutritious. He said, “Painted cakes do satisfy hunger. Aside from painted cakes, there is no other way to satisfy hunger.”

My photographs are painted cakes. My poems are painted cakes. This book is a painted cake. Aside from painted cakes, there is no other way to communicate what I am feeling, what I am thinking.

Artistic creations are no less real than reality. From Dogen’s perspective, they are not an abstraction of reality. They are indeed reality itself. Your poems, your art, are reality. What Dogen is saying is that we need to get past our dualistic perception of the universe and the self. We need to train ourselves not to accept either the imaginings or reality at the expense of one another. They are, in fact, nondual and a clear expression of the truth.

Reality is nondual. When we are awake, all dualities—self and other, is and is not, good and bad—merge into a single suchness of the moment. They are no longer seen in the realm of this and that, the realm of separation. All the permutations and combinations that we go through in defining things always ultimately come down to right here, right now, right where you stand.

What you are looking for is who is looking.

S T. FRANCIS OF ASSISI

Yet, when we first come in contact with spiritual practice, we approach it from a deeply ingrained dualistic perspective. We perceive our whole universe in a dualistic way. Our philosophy, education, medicine, psychology, and politics are dualistic. The way we’ve structured the universe in our minds, the way we understand things is always from a conditioned dualistic perspective. Within that conditioning, our art is also dualistic. It is about self and other, subject and object, artist and audience.

The most powerful medicine for our dualism is to uncover the still point resting within all the dualities. This is the work that takes us past the separations and conditioning to the very ground of being. When we really make contact with the still point, we make contact with the core teaching of Zen. As we’ve seen before, the Heart Sutra refers to it as the experience of “no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind; no color, sound, smell, taste, touch, phenomena; no realm of sight, no realm of consciousness.” All the myriad forms dissolve.

But now, what we have is a useless lump of meat sitting on a meditation cushion. It doesn’t see, it doesn’t hear, it doesn’t think, it doesn’t love, it doesn’t hate, it doesn’t dance, it doesn’t cry. It just sits there like a big blob of protoplasm. Is that what our life is? Is that the still point? Definitely not! Consider the life of Soen Roshi, or any of the Zen teachers introduced in this book. They were full of life, constantly manifesting life. So there must be something more, something that goes beyond that place of no eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind. We need to see and live beyond the quietism of the still point.

And so the process continues. We come down from the holy peak into the world. Again, the Heart Sutra states: “Form is no other than emptiness; emptiness is no other than form; form is exactly emptiness, emptiness exactly form.” Having let go of the absolute perspective, the two apparent dualities are now merged in one reality. When mind and objects are a single reality, all dualities merge. You and I are the same thing. But I’m not you and you’re not me. Both of these facts exist simultaneously. Both of these facts are true.

This truth was expressed by the ancient master Shitou Xiqian in his liturgical poem “The Merging of Differences,” in which he said:

Each and all, the subjective and objective

Spheres are related

And at the same time independent.

Related and yet working differently,

Though each keeps its own place . . .

. . . Within light there is darkness,

But do not try to understand that darkness.

Within darkness there is light,

But do not look for that light.

Light and darkness are a pair,

Like the foot before and the foot behind in walking.

Each thing has its own intrinsic value

And is related to everything else in function and position.

Ordinary life fits the absolute as a box and its lid.

The absolute works together with the relative

Like two arrows meeting in midair.

It’s hard to get a handle on this description of reality. It is a fundamental paradox of our lives, one that is impossible to resolve intellectually—but it doesn’t have to be. It simply needs to be manifested in our lives.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

I am large, I contain the multitudes.

WALT WHITMAN

That’s why practice is so important. The essence of our lives, the heart of the matter is essentially ineffable. You’ll never be able to explain it. No teacher will ever be able to explain it. The Buddha could never explain it. Why? Because it doesn’t come from the outside, from a Buddha or a master, a book or a phrase. It already resides in you. It’s already your life. The problem is that it’s obscured, buried under layers of conditioning, under habitual ways of using our minds.

In the depths of stillness all words melt away,

clouds disperse and it vividly appears before you.

JOHN DAIDO LOOR I

What’s being offered in all the incredible teaching of Zen and the Zen arts is simply a process. If you walk away from this book thinking you understand Zen or creativity, then I have failed. If everything goes well, you will never understand it. On the other hand, if you can appreciate the process and are willing to engage it, you will have a way to return to your inherent perfection, the intrinsic wisdom of your life.