CHAPTER VII

Extractivist-Oligarchic Type

In comparison with the other four types presented in this research, the extractivist-oligarchic (EO) type shares most features with the donor-dependent orthodoxy (DDO) type—to be discussed in chapter 8—and yet EO cases are not donor-dependent, nor did they follow orthodox policy prescriptions during the commodity boom years. As in the DDO configuration, and unlike the remaining three types, EO denotes states that lack a large domestic capitalist class with substantial autonomy from the state. As with DDO, in EO cases, access to the state and thence to networks of transnational capital is the major source of both economic and political power, where rule is secured through leveraging control of the state to appropriate and distribute resources along networks of patron–client relations.1

The most salient difference between EO and DDO types, in terms of explaining their distinct trajectories over the boom years, lies in their differing levels of engagement with the transnational vectors from which state managers’ economic resources flow, particularly in the preboom years. In DDO type cases, since at least the 1990s, the most important source of capital flowing through the state came in the form of aid. Aid dependence brought high levels of conditionality, and, in the context of very low levels of state capacity, many elements of neoliberal reform programs were directly devised and supervised by donors. As we will discuss in chapter 8, without strong, organized domestic capitalist or popular voices to press for change, DDO state managers have found it difficult, or perhaps undesirable, to articulate and implement any substantive reorientations away from neoliberal trajectories, since this would involve a break with the priorities of donors, upon whose financing streams political elites have long depended to cement their power. Importantly, unlike DDO cases, neither Kazakhstan nor Angola entered the period of the commodity boom with state structures dependent on donor funding and technical capacity. In consequence, while the two EO states arguably may be seriously lacking in any coherent development strategy, their actions are less constrained by a neoliberal bureaucratic imprint left by decades of donor tutelage.

After a brief introduction, I will begin by outlining the features of the EO trajectory, noting its similarities to the rentier state model. As with some of the classic cases of oil-based rentierism, it may well be that, under commodity boom conditions, the sheer quantity of extractive surplus that flows through the domestic economy is sufficient to spark a true process of accumulation, rather than simple distribution, even if this is accompanied by predictably high levels of waste and predation (Ovadia 2016, 2018).

Next, I will turn to the impact of the commodity boom in the two EO cases, Angola and Kazakhstan, showing that increases in oil prices and production volumes have been largely responsible for massively increasing government revenues and expenditures in both states. It is this fiscal capacity to set policy, independent of external pressures, that has enabled the distinctive blending of developmental and predatory policies and behaviors, together with a blurring of the lines between public and private sectors, that has come to define the political economy of Kazakhstan and Angola. Finally, I focus on the domestic political economy of the two cases, with a more extended discussion of Angola (used as the exemplar case here), detailing its political-economic path since emerging from civil war in 2002.

The most striking ideotypical feature of EO states is a strongly stated developmentalist orientation, outwardly reflected by often impressive investment in infrastructure and urban centers, behind which lies a pervasive (though perhaps mutating) system of clientelistic rent distribution that undergirds the logic of governance. The scale and quantity of development projects, along with the opportunities for rent-seeking which they bring, were turbocharged during the boom years by an accelerating flow of resource revenues. To some degree, these processes seem to have brought genuine accumulation, too.

Echoing a political-economic pattern seen across many locations and eras—including a number of Southern states during the neoliberal period—patronage flows out from a powerful central authority, facilitating the enrichment of a thin stratum of elites. For EO type states under commodity boom conditions, though, this equation has been modified by the centrality of a high modernist vision of development, the articulation of which forms a key part of government efforts to maintain hegemony. The result is that a focus on large-scale infrastructure development—for instance, in housing, transport, or urban transformation—provides a convenient channel through which to reward allies and maintain loyalties, although this channel, for all its inefficiency and predation, still produced tangible, if highly uneven, improvements.

As will be seen more clearly in discussion of the two cases, without the vast increases in resource revenues (relative to gross domestic product) brought by the commodity boom, this EO model would not have been viable. This is not to say that a less predatory system, not grounded in patronage relations, would have otherwise emerged. However, the sheer scale of government-funded initiatives seen in the EO cases simply would not have been possible during a sustained period of low hydrocarbon prices. Dependence upon international financial institution support—likely in such a context, given high levels of government indebtedness—would have effectively ruled out the officially promoted policy package, with its starring role for publicly led investment.

With access to abundant resource revenues, though, road networks were overhauled, cities were created or reconstructed, and new industrial ventures were pursued, in programs that all appear to lie somewhat along a continuum between developmental and predatory intent. In some senses, these characteristics recall—or, in the worst cases, perhaps parody—the ambitious plans for industrialization and modernization advocated by Southern states during the era of post–World War II decolonization. In other ways, there is a self-conscious appropriation of contemporary intellectual tropes, particularly the linguistic trappings of the developmental state concept. In this way, for example, even the highly inequitable sharing of the spoils gained from export revenues can be presented as state nurturing of a rising national bourgeoisie (Power 2012).

Importantly, state-owned extractive companies themselves were very much run along commercial, profit-oriented lines, particularly in hydrocarbons, meaning that the rents that underpinned the model continued to flow as long as export prices remained sufficiently high. Thus, both states came under increasing economic pressure with the end of the boom, but they have responded somewhat differently. While Kazakhstan has cut spending in some areas, it also sought to prop up its overall economic model with stimulus amounting to 12 percent of GDP from 2014 to 2017 (Brown 2018). Angola, meanwhile, has been more severely affected and appears to have embarked upon a more orthodox stabilization program, involving a raft of privatizations (International Monetary Fund 2018; CNBC Africa 2018).

The two cases took rather different paths through the neoliberal era and into a reassertion of policy autonomy in the 2000s. Neoliberalism and its constraints, to some extent, skipped Angola, which was embroiled in civil war from the time of its independence, in 1973, until 2002. Though some efforts were made to organize a conference with donors, following the end of hostilities, a combination of rising oil prices and Chinese investment allowed the victorious Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, or MPLA) to overcome a postwar fiscal crisis without engaging IFIs and traditional donors.

In contrast, Kazakhstan, formerly part of the Soviet Union, entered a period of economic liberalization following its independence, in 1991. The reforms were encouraged and financially supported by the IFIs (Cooley 2003), with the speed and extent of the process lying somewhere between shock therapy in Russia and recalcitrance in Turkmenistan (Pomfret and Anderson 2001). In terms of the lasting effects of neoliberalization, though, Kazakhstan differed from the otherwise broadly comparable postsocialist DDO case of Mongolia in two crucial respects, which together account for Kazakhstan breaking with a liberalizing path while Mongolia did not.

First, Kazakhstan possessed (and retained) important state-owned gas and oil companies, which continued to provide a key source of external rents and would, during the boom years, present an easier means for the state to enter into partnerships with transnational extractive companies, on better terms (Vivoda 2009). Second, Kazakhstan’s relationship with Northern interests and IFIs never could be primarily characterized as that of donor–recipient, as table 7.1 shows. Thus, because Kazakhstan was far less reliant than the likes of Mongolia on international extractive companies and donors as a source of technical capacity and, probably more importantly, less dependent on donors as a wellspring of government financing, during the mid-2000s, Kazakhstan was able to turn decisively away from its previous trajectory of neoliberalization.

Official development assistance as a percentage of gross national income

|

1991 |

1996 |

2001 |

2006 |

2011 |

||||||

|

Angola* |

2.8 |

7.8 |

3.8 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

|||||

|

Kazakhstan |

0.1 (1993) |

0.6 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

|||||

|

Mongolia |

3.0 |

15.0 |

16.9 |

6.1 |

4.4 |

*Angola’s official development assistance receipts did temporarily increase in the mid-1990s, peaking at 23 percent of gross national income in 1994, though this was overwhelmingly composed of humanitarian aid related to an internationally brokered peace deal, which was not sustained.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

This external autonomy is, in both cases, combined with a central state that is far more powerful than weak capitalists or any other domestic groups, producing political-economic orientations in both EO states that act to strengthen the direct participation of the state (and state-owned enterprises) in the economy and to distribute patronage to key allies. (Similar trends were observed elsewhere, in earlier booms; see, for example, Winters [1996] on Indonesia.) This is broadly consistent with several accounts that view Kazakhstan, along with other energy-exporting Central Asian states, as new examples of the rentier state (such as Franke, Gawrich, and Alakbarov 2009; Robinson 2007), and with others that consider it self-evident that postwar Angola also fills the bill (Sidaway 2007; Wiig and Kolstad 2012).

There are clear indications, in both cases, that an oligarchy connected to the upper reaches of the state controls the internal distribution of hydrocarbon rents, funneling a large proportion to its own consumption and prestige projects (particularly the radical overhaul of urban landscapes in Luanda and Astana). A further share is diverted toward co-opting potential internal threats via distribution of patronage resources, such as through the incorporation of former rebel commanders into patron–client networks in Angola. In Kazakhstan, a serious opposition from organized interest groups, including an emerging capitalist strata, is more dangerous. As a result, the government has acted to co-opt business groups and quell occasional urban unrest by extending access to rents to a second tier of elites (Junisbai 2010, 2012; Isaacs 2013).

The Extractivist-Oligarchic Ideal Type

In spite of the developmentalist trappings, in several respects, the closest conceptual comparator to the EO type is the rentier state (RS). First suggested by Mahdavy (1970), in relation to prerevolutionary Iran, and most prominently developed by Beblawi and Luciani (1987), rentier states are usually defined by their reliance upon external sources of revenue, accruing principally to the government, which controls the consumption and distribution of these flows. The state therefore essentially acts as landlord or gatekeeper, pocketing unearned rents rather than levying taxes on productive activity.2

Much of the literature on rentier states is linked to notions of the resource curse (Karl 1997; Yates 1996; Jensen and Wantchekon 2004; among many others), with the claim that predation and poor institutional quality tend to arise through the lack of need to extract taxation from domestic sources. In this account, freedom from the need to levy taxes blocks the emergence of the classic liberal social contract of tax revenues supplied consensually by the citizenry in exchange for representation and government accountability (Ross 2001). Unconstrained by the need to respond to taxpayer demands, government tends to become inefficient, corrupt, and perhaps authoritarian (Skocpol 1982). Worse, state managers can divert a portion of their rents toward establishing a system of patronage through which any potentially restful social groups can be bought off and pacified. Given a seemingly guaranteed revenue stream, there also are few incentives for state managers to encourage economic diversification or, more broadly, development of the economy, particularly since such processes may well serve to create alternative bases of power on the domestic scene.

One of the most striking aspects of this schema is its degree of compatibility, despite a rather different theoretical heritage, with much of the conceptual apparatus I employ to explain links between domestic class configuration and political-economic regime type. A retooling of the rentier state model along these lines, in fact, is extremely useful in demonstrating these connections for the EO type.3 The RS departure point—that the lack of state reliance upon taxation removes a key lever of social pressure with which to influence the behavior of state managers—may be modified to note, instead, that the lack of dependence on the actions of domestic capital precludes the application of domestic capitalist structural power in influencing the state. Indeed, Ross (2001) notes that rentier states operate “autonomously” from society.4

Where rentier states’ autonomy ends, though, is in the circumstances of their insertion into the global market for their commodity exports.5 This is clearly seen in many of the cases discussed in other chapters (not least with regard to the donor-dependent orthodoxy type), given the ability of IFIs, donors, and capital markets to advance neoliberal conditionalities during an era of low commodity prices. Some states with particularly high export volumes and relatively capable parastatal extractive companies—such as Venezuela—certainly were able to use resource rents as a means of delaying or minimizing reforms during much of the neoliberal period (Coronil 1997, 370; Hertog 2010). Even in these cases, though, a liberalizing direction of travel was clear in the years prior to the commodity boom.

At this point, the significance of a legacy of aid dependence becomes crucial for unraveling the distinct trajectories of EO and DDO states under boom conditions. For those rentier-like states that, during the neoliberal era, came to rely heavily upon aid in order to fulfill basic state functions, there clearly was an impact on the shape and culture of the bureaucracy, through such measures as insisted-upon organizational reform, direct donor input into spending choices and staff training, and others. Probably more importantly, however—and as will be discussed in more detail in chapter 8—as aid flows rather than resource revenues became the major source of rents captured by the state, aid correspondingly replaced export revenue as the nexus of the distribution and patronage networks underpinning the authority of political elites (see, for instance, Szeftel 2000; Moore 2004). Understandably, then, while state elites in DDO cases are undoubtedly aware of the potential for capturing a larger proportion of the extractive surplus, and in some instances have made rather inconsistent attempts to do so, they are reluctant to endanger existing flows of aid rents by explicitly abandoning their donor-led development agenda.

Without aid rents to protect, state managers in the EO cases, unlike their DDO counterparts, entered the boom without the need to hedge their bets between resource revenue maximization and maintaining the favor of donors. While, again, this difference does not necessarily translate into a more coherent approach to development, EO governments under conditions of high export prices are left with a relatively free hand when it comes to setting policy. In effect, then, the revenues flowing into state coffers during the commodity boom have allowed EO type state managers the kind of policy autonomy (from both domestic society and external capital) commonly associated with the rentier state, for better or worse.

There are further parallels between EO cases and their West Asian comparators, which go beyond, and in some senses confound, the RS model. Although the sincerity of EO governments’ developmental agendas is at the very least questionable, the sheer volume of commodity rent passing through the domestic economy may well be enough to spark true processes of accumulation rather than simple distribution of the extractive surplus.

Interestingly, this situation seems to recall the historical political-economic path already taken by the Gulf monarchies. Hanieh (2011, chap. 2) provides an account in which the circulation of sufficiently large quantities of oil rents spurs a twin-track process of capitalist formation. Here, rulers’ distribution of real estate and high-level public sector jobs to relatives, prominent allies, and older merchant families, while initially allocative or even parasitic, eventually proved to be the basis for future accumulation. Beyond this inner circle, emerging business groups generally were not permitted any direct control over extractive sectors, but they did begin to provide ancillary services around the oil and gas industries—in construction, basic manufacturing, or transport, for instance.

With the enrichment of bureaucrats through payments for contracts (from both internal and external sources) and states moving to offer interest-free loans to nascent capitalists (including those outside the rulers’ inner circles), discerning a clear separation between state and capital, as well as predation and accumulation, became difficult. Nevertheless, and confounding expectations, most of the Gulf states now house successful downstream industries, usually state owned, which serve primarily as vehicles for “true” capital accumulation rather than patrimonial rent allocation (Hertog 2010).6 Hanieh’s (2011, 15) comparison here is with Engels’s description of the Russian state as providing a hothouse for the growth of the capitalist class. While there are marked differences, particularly in the sense that the dominance of capital-intensive extraction in the Gulf has not involved the creation of a working class,7 the other side of the ledger, where the state incubates nascent capitalists via subsidies and the granting of concessions, is rather similar.8

Though such processes are less advanced in Kazakhstan, and particularly in Angola, they do appear to have been occurring to some degree during the boom, with high prices acting as an accelerant in the formation of capitalist classes overlapping with and highly dependent upon the state. In both cases, hydrocarbon rents are directly channeled into a mix of allocative and accumulative activities, through state-owned companies answerable directly to the president. In Angola, this has prompted the rise of a new post–civil war economic elite, which, while seemingly harboring little interest in long-term productive investment, represents a shift from the pure predation of exchange rate manipulation and war profiteering of the 1990s (Soares de Oliveira 2015, chap. 1). In Kazakhstan, post-Soviet upheaval did allow for the emergence of a somewhat more independent group of capitalists, who were not linked to extraction and had fewer ties to state officials. Although this group has periodically been a source of opposition to the government, its role increasingly appears analogous to that of the second-tier Gulf capitalists—excluded from energy sectors but otherwise appeased via a share of government contracts.

External Market Conditions and Their Political-Economic Implications

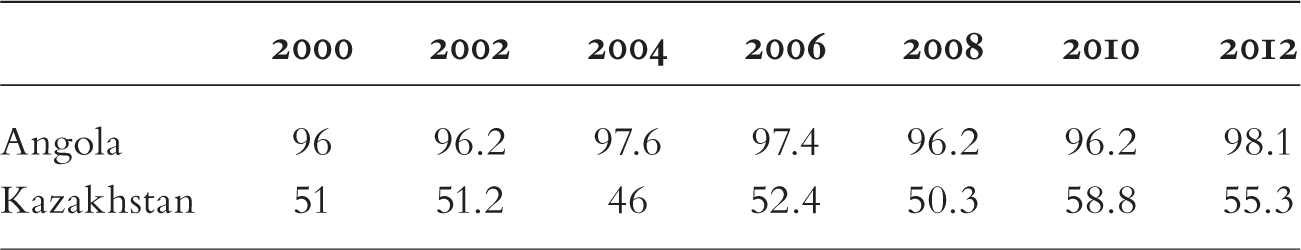

Crude oil dominates the export profile of both Angola and Kazakhstan, though to a lesser extent in Kazakhstan, which also exports minor amounts of copper, zinc, and natural gas as well as wheat. With most production occurring offshore, the Angolan oil sector was not unduly disturbed by the country’s long civil war, and petroleum has accounted for more than 90 percent of exports since the early 1990s (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development n.d.). In Kazakhstan, the average has been above 50 percent since 2005 (table 7.2), with a large boost possible in the future as production at the Kashagan Field ramps up.9

Oil as a percentage of total merchandise export value

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity.

Although both cases possessed important oil sectors prior to the 2000s, a clear line can be traced between the boom in oil prices, expanding export receipts for the two states, and huge increases in government revenue and expenditure over the same period. Figure 7.1 shows the progression of total merchandise export values in Angola and Kazakhstan since 1998, together with that of the average international spot price per barrel of crude oil. As can be seen, the three curves follow similar trends, with an initial increase in oil prices during the late 1990s, reflected in export revenue movements (though weakly), followed by a stronger correspondence among indicators over the course of the commodity boom proper, beginning in 2003.

The relative weight of hydrocarbons in the export sectors of both cases suggests that the commodity boom would be associated with positive economic trends in Angola and Kazakhstan. However, establishing a connection between oil prices and government revenues and expenditures provides much stronger evidence linking change in commodity markets to a newfound capacity to implement independent development strategies. Comprehensive and accurate figures relating to the importance of oil revenues in government accounts are complicated, in the cases of Kazakhstan and Angola, by the fact that parastatals (Samruk-Kazyna and Sonangol) control a large proportion of these funds and directly allocate them to development projects, bypassing the regular budget process.

Figure 7.1 Angola’s and Kazakhstan’s total merchandise exports relative to oil prices, 1998–2014.

Sources: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTADStat data center; World Bank, Commodity Price Data—Pink Sheet Data.

Nevertheless, IMF estimates of oil revenue as a percentage of total revenue in Angola are 80% for 2011 and 75% in 2013, while equivalent figures are 53% (2011) and 47% (2013) for Kazakhstan (International Monetary Fund 2014a; 2017). Given that export revenue, powered by the resource boom, rose so quickly and that oil payments have played such a large role in public finances, it is hardly surprising that government spending expanded rapidly in both EO states since 2003. Figure 7.2 illustrates this in the case of Angola, showing an index value for both general government revenue and expenditure, drawn from IMF statistics, which may well underestimate their growth, again because of the likely omission of many Sonangol activities. Adjusted for inflation, revenue had, by 2005, doubled from its 2000 level, and had tripled by 2011, after a dip in 2009, following the global financial crisis. Similar trends are observed in expenditure, though it is worth noting that the eventual decision on the part of the Angolan authorities to turn to the International Monetary Fund, in 2009, came after the growth in spending had begun to outstrip that of revenue and was not fully adjusted downward to compensate for the postcrisis blip in receipts. While the ensuing $1.4 billion loan from the fund did not come with particularly stringent policy conditionalities attached, these events prefigured the greater apparent shift in policy that has more recently come with a more sustained drop in oil prices (International Monetary Fund 2018).

Figure 7.2 Angola revenue and expenditure indexes (in real), 2000–2014. Calculated from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database.

The argument for a connection between the commodity boom and the ability of resource-rich states to break with neoliberal constraints rests primarily upon the impact of Chinese demand on the structure of global commodity markets rather than necessarily upon any direct bilateral trade links. However, it is interesting to note that, in this regard, China has played a rather important direct role in the expansion of Kazakhstani and Angolan resource exports. A key plank of Kazakhstani foreign policy following independence has been the desire to balance Russian, Chinese, and Western influence, something which extends to external economic relations. While it is therefore no surprise to find that no one market dominates Kazakhstan’s exports, China’s share has grown steadily since 2000, becoming Kazakhstan’s number one export destination by 2008. By 2012, one-fifth of Kazakhstani exports went to China—more than double the proportion that went to Russia, in second place (United Nations Comtrade n.d.).

The reentry of China into Angola has been a major focal point of recent media and academic interest in China–Africa relations, and the signing of a $2 billion oil-backed loan deal with China’s Eximbank, in 2004, was of major significance. Indeed, the “Angola model” has become the standard term for the system of commodity-backed loans for infrastructure that were advanced by Chinese policy banks to many Southern governments in subsequent years (Brautigam 2009, 73–77; Brautigam and Gallagher 2014; Tan-Mullins, Mohan, and Power 2010). The terms of this loan and of similar deals with the Angolan government have led to the involvement of both public and private Chinese entities in Angolan construction and infrastructure, though, perhaps surprisingly, Chinese firms are only peripheral players in the extraction of the country’s oil (Corkin 2011).

Where the bilateral relationship certainly has strengthened is in trade. The Chinese share of Angolan oil exports jumped, following the end of the civil war, from 16.5 percent in 2002 to 41 percent two years later, and China has been the number one buyer of Angolan oil every year since 2008 (with a 62 percent share in 2008) (Observatory of Economic Complexity n.d.). Viewed from the other side, Angola is now the second largest supplier of petroleum to China, after Saudi Arabia (Weimer and Vines 2012). Nevertheless, though China has been an important trade partner and, in the Angolan case, creditor in the commodity boom period, it is the takeoff in the oil market, combined with particular domestic conjunctural factors—the end of the Angolan Civil War, new extractive projects in Kazakhstan—that have allowed both EO states the fiscal leeway to assemble their distinctive post-neoliberal orientations.

Angola

The pace of change in Angola since the end of civil war, in 2002, has been remarkable, with the economy becoming sub-Saharan Africa’s third largest by 2005 and GDP growth peaking at 23.2 percent two years later (World Bank n.d.). This is despite a deeply troubled twentieth-century history. A liberation struggle against Portuguese colonialism began in 1961 but was only ended by the outbreak of revolution in Lisbon in 1974. By the time Angolan independence was declared, a year later, three domestic factions were fighting for control.

Though the ostensibly socialist MPLA held the capital, Luanda, throughout, the civil war grew larger in scale and duration as it morphed into a Cold War proxy conflict. The Soviet Union sent significant military aid to the MPLA, and the United States provided military assistance to the União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola, or UNITA), based in the diamond-producing highlands. The conflict escalated to the point of direct military involvement on the part of both Cuba and apartheid South Africa, but it continued for more than a decade after the end of the Cold War and the withdrawal of foreign forces, ending only with the death of UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi in 2002. A aside from low-level conflict in the enclave of Cabinda, thereafter President José Eduardo dos Santos ruled largely unchallenged until he stepped down in 2017.

During the 1990s, both sides in the civil war financed their war efforts almost entirely through the sale of oil (in the case of the MPLA) or diamonds (UNITA) (le Billon 2001). However, there clearly was huge capacity for the expansion of oil production under peacetime conditions, and it is the realization of this potential—with rapid growth in oil exports, from $5.9 billion in 2002 to $63.2 billion in 2012 (Observatory of Economic Complexity n.d.)—which was almost single-handedly responsible for the booming economy.

Having developed a “parallel state” apparatus centered on national oil company Sonangol during the 1990s (Soares de Oliveira 2007), the victorious MPLA leaders entered peacetime at a moment of rising prices and with an ideal vehicle through which to maximize their take from the growing oil revenue. These advantages, together with the involvement of China and other nontraditional donors, afforded President dos Santos the leeway to manage Angola’s reengagement with the world largely on Angolan terms. This, in turn, left the government free to pursue a state-led, high modernist development model, which, in many senses, may be more rhetorical than substantive but nevertheless brought an impressive reconstruction of infrastructure (Power 2012; Soares de Oliveira 2015, 72–82). Clearly, though, much economic activity is blighted by elite predation, and development plans often actively exclude the vast majority of the population (Ovadia 2013).

At the end of the war, any ambitious development schemes seemed a distant prospect. With an impending fiscal crisis, it might have seemed inevitable that the government would establish an orthodox relationship with Northern donors and creditors and thus enact the neoliberal reforms that such an arrangement would require. While the government negotiated with the international financial institutions and repeatedly called for a donor conference in the initial postwar years, however, international demands that Angola submit to an IMF monitoring program and account for apparently missing oil revenue were largely ignored. Though clearly much of the Angolan objection can be ascribed to a reluctance to demystify opaque oil financing, Power (2012) points out that another concern was the prospect of neoliberal paring back of the state administration at a time when a primary MPLA goal was the territorial consolidation of its rule. More generally, the postwar government had an understandable sensitivity about questions of sovereignty and, crucially, unlike the majority of sub-Saharan states, this was Angola’s first real encounter with conditionality, the initial stages of which had also been resisted, in various ways, by several neighboring states during the 1980s (Mosley et al. 1991).

Had the situation persisted, Angola, too, might have been forced to reluctantly engage with donor demands. Instead, a combination of rising oil prices, new deepwater fields coming on line, and the arrival of a new creditor, in the shape of China, allowed the government to largely define its own approach to economic management.10 The involvement of China is by far the most prominent of these factors noted in the literature, and not without reason. Oil-backed loans from China’s Eximbank (and later from the International Commercial Bank of China), beginning with a $2 billion deal in 2004 (Brautigam and Gallagher 2014), have become the paradigmatic examples of China’s now widespread practice of offering commodity-backed loans to Southern states—the Angola model.

As Brautigam (2009, 275) points out, the first Chinese loan was not entirely novel, in that Angola had already contracted large amounts of oil-backed debt, mainly owed to Northern banks, over the 1990s. This said, the Eximbank deal was different in important respects. First, the terms were far more generous than those previously offered by Northern commercial banks, with low interest rates and a much longer repayment period. Second, this loan and the subsequent commodity-backed credits were tied to infrastructure projects, with the stipulation that 70 percent of ensuing contracts would be awarded to Chinese firms (Soares de Oliveira 2015, 56).

It is quite clear that large-scale loans from Chinese policy banks, to the tune of perhaps $20 billion by 2014 (Brautigam and Gallagher 2014), have been a major part of the post–civil war Angolan development story. For dos Santos, however, this was not simply about shifting dependence away from the global North and toward China. As in Kazakhstan, as we will see, the new Chinese presence was rather astutely parlayed into a greater freedom of government action, with a larger array of potential international partners and thus enhanced bargaining power for the Angolan side in choosing with whom to engage. Indeed, within a year of the first Eximbank deal, Angola secured two loans from British and French banks, totaling $4.35 billion and with commercial rate, though reasonable, terms (Brautigam 2009, 276).

Despite the political importance of oil-backed loans from the People’s Republic of China, these did not lead to Chinese dominance, even in the oil sector, where Chinese companies were granted only limited access in comparison with more technically advanced Western firms (Soares de Oliveira 2015, 174). In line with the MPLA aim of diversification of partners, capital from other sources, including Brazil, Portugal, and Israel, is also very active in Angola, with the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht becoming the largest private employer in the country.

Interestingly, Brautigam (2011, 277) cites a comment from the Angolan finance ministry that the 2002–2004 engagement with the IMF was primarily sought as a means of gaining an IMF seal of approval, which would then allow the government to continue raising capital from Northern banks at reasonable rates. The fact that such loans were forthcoming, as were the British and French credits, only a few years after rejecting the IMFs advances, points to rising production volumes and prices in the oil sector as a more fundamental basis of Angola’s ability to maintain policy independence than direct Chinese engagement alone. Though it is perhaps possible that Chinese activities in Angola over the mid-2000s brought something of a spotlight to Angola, which might have helped to enthuse Northern banks, this is hardly the sort of green light for banks and capital markets that a positive assessment from the IMF usually provides. The fact that, even without IFI endorsement, Northern finance flooded into Angola over the next decade is surely evidence of the power of the commodity boom to attract capital inflows to resource-rich locations—even to a historically unstable, low-income state with poor infrastructure and little evidence of “sound” institutions or policy beyond a basic orthodox macroeconomic framework.

In 2009, following the global financial crisis, Angola did turn to the IMF for a $1.4 billion loan. However, even at this point of relative economic weakness, the comparatively lax conditions asked of Angola are striking, with the MPLA government essentially disregarding requested reforms that were not to their liking (Soares de Oliveira 2015, 178). The desire on the part of the fund to establish a presence in Angola, which by this point had become Africa’s third-largest economy, shows a major shift in bargaining power from the early post–civil war years. As Soares de Oliveira points out, the IMF had gone from a complete refusal to engage, on the basis of $4.22 billion hole in government finances as of 2001, to sympathetic concern (but little condemnation) over a $32 billion gap (or 25 percent of GDP) ten years later.

The rising level of unaccounted-for funds are the direct result of the growth of a parallel state system, which bypasses the formal institutions of public administration (Soares de Oliveira 2007; Shaxston 2007). During the civil war, the state-owned Sonangol possessed a much higher credit rating than the government itself—largely because of the offshore location of the majority of its oil reserves—and thus became the main recipient of international loans. Oil-backed financing, coordinated through Sonangol, thus became the main means of funding the civil war in the 1990s.

During the postwar period, the company rose to become Africa’s second largest, with a range of subsidiaries across shipping, banking, insurance, and real estate, along with overseas interests in Portugal, Brazil, Iraq, Venezuela, South Sudan, Algeria, and Cuba (Soares de Oliveira 2015, 185). Sonangol and the Gabinete de Reconstrução Nacional (National Reconstruction Cabinet), responsible for allocating the majority of (quasi) public funds, are both very much under the direct control of the presidency and clearly serve as vehicles for the enrichment of a thin stratum of MPLA elites and their allies (Ovadia 2013). Nevertheless, Sonangol itself appears to be run with a high level of technical competence, and it is undeniable that large-scale reconstruction efforts have taken place, particularly in infrastructure, since 2002. It may well be possible to ascribe many of the developmental advances that have occurred to little more than a side effect of the opportunities for enrichment arising from project deals, particularly when these include joint ventures with foreign partners. Even so, and somewhat similar to the experience of the Gulf states, the lines between predatory rentierism and accumulation, as well as between the state and private enterprise, are increasingly difficult to discern.

However, even if the MPLA ran a narrow, clientelistic system during the latter years of the civil war, there appears to have been a realization that a somewhat broader-based nation-building and development project was now necessary to secure the foundations of their rule. The concentration of efforts and funding in infrastructure, especially on the reconstruction and extension of the road and rail networks, to the tune of $4.3 billion per year, or 14 percent of GDP from 2004 to 2010 (Pushak and Foster 2011), is likely to have been of most benefit to a broad swath of the population. Overall, however, rural areas and the peri-urban musseques (slums) were ignored in favor of an aspiring urban middle class, encompassing perhaps a half million of the country’s 20 million inhabitants. Improvements for this social layer came through the provision of house and car ownership, the extension of pensions, and a doubling of the number of civil servants, to four hundred thousand (Soares de Oliveira 2015, 82–83). The growing number of Angolans with disposable income added a second layer to the elite-driven urban gentrification, seen most obviously around Luanda’s seafront, with the development of new supermarkets, shopping centers, and restaurants to a modernizing blueprint and with Dubai held up as a reference point (Power 2012).

With regard to the nascent middle classes, it is again difficult to mark a clear distinction between the extension of clientelistic networks as the basis for regime stability and a process of genuine class formation. Although it may not fit with a traditional RS schema, in this, Angola seemed to be following in the footsteps of several Gulf States that were largely excluded from fruits of the oil boom, though with a much larger domestic population. Hanieh’s (2011) evocation of Engels’s state as hothouse is particularly appropriate here, though with oil revenue utilized as fertilizer and the government very much in control of the process. As Soares de Oliveira (2015, 83) puts it, “The MPLA wants to internalize the process of class formation: through a limited distribution of the oil rent, it seeks to engineer the rise of a loyal and dependent state class rather than create the conditions for the spontaneous emergence of an unattached and unreliable middle class.”

One of the more interesting aspects of the trajectory of Angolan development over the boom years was the manner in which its claimed intellectual basis shifted and solidified behind a kind of high modernist developmentalism quite at odds with neoliberal norms, and certainly with donor preferences (Sogge 2011; Soares de Oliveira 2011). The justification for favoring a relatively narrow band of society was premised on the creation of a so-called national bourgeoisie, with this term variously used to describe the enrichment of a small number of oligarchs (with, for example, 85 percent of Angolan banking credit being directed to around two hundred individuals) as well as in the somewhat broader sense of the creation of an urban consumer class. Rentierism and multilevel patronage thus could be justified in developmental terms, drawing on a multifaceted spectrum of influences, ranging from the final years of Portuguese colonialism to the Marxist roots of the MPLA to the image of Brazil as an idealized model society. While there is little suggestion that the Chinese model was interrogated in any depth by Angolan officials, the emphasis on experimentation and state-led megaprojects is familiar. The national bourgeoisie trope also seems very reminiscent of the desire to promote a black capitalist class in postapartheid South Africa (see chapter 9).

Beyond infrastructure provision and Sonangol, there were relatively few indications of long-term development planning on the part of government or capital. Several large-scale projects, which resemble pre-neoliberal industrialization efforts, were undertaken, chiming with the claimed developmentalist orientation of the state. Most prominent is the special economic zone outside Luanda. The special economic zone scheme, in its first phase, involves the development of seventy-three state industries, described by Soares de Oliveira as “a sort of theme park of import substitution industrialization” (Soares de Oliveira 2015, 63)—an apt summation of the government’s approach to development as a whole.

While the costs associated with the special economic zone are difficult to ascertain, its workings are emblematic of the kinds of initiatives pursued since the end of the civil war. The various factories that comprise the facility were publicly funded, but they were developed by foreign firms as turnkey projects and then handed over to the government upon completion. That most of these factories either failed to produce anything or else ran at a loss seems to be due to a lack of interest in long-term planning in favor of the use of such schemes for short-term enrichment of favored insiders, beginning with the various contracts involved in the construction of the venture. Next, after a completed project was handed over to the government, it often would be quickly privatized, commencing another round of rent-seeking. According to Soares de Oliveira (2015, 63–71), this pattern was been repeated across a range of initiatives that, on a surface level, resembled familiar state-led developmentalism. These included kibbutz-style agricultural schemes, Chinese built-housing complexes, and a state-run network designed to purchase and distribute food from small producers, which apparently devolved into a conventional, privately run supermarket chain.

Kazakhstan

Although it was possessed of both a much higher per capita GDP and more autonomous capitalist elements, Kazakhstan’s experience of the boom shared many important features with that of Angola and the EO ideal type. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, in 1991, Kazakh Communist Party leader Nursultan Nazarbayev took over as president of the newly independent country and remained at the helm of an increasingly authoritarian state up until 2019. Nazarbayev’s paternalistic rule was apparently popular, with its legitimacy built upon an ability to deliver relatively rapid economic growth after the 1990s falloff common to almost all post-Soviet states (Koch 2013).

During this initial period after independence, neoliberal reform and privatization produced a new class of oligarch (Spechler 2008), though, in contrast to neighboring Russia, the state retained control of most strategic industries. Thus, the new capitalists, from early on, depended heavily on their ties to the presidency (Libman 2010), in a system resembling the “power vertical” of Putin’s Russia (Isaacs 2010), rather than relying on loans from domestic capital, as with the Yeltsin government. The finansovo-promyshlenye gruppy, or financial-industrial groups, which emerged in the decade or so following the collapse of the Soviet Union, may be divided into two tiers (Junisbai 2010). The outer grouping consists of oligarchs who are permitted to accrue large fortunes in a more-or-less competitive environment. However, these figures were not allowed to own firms in the hydrocarbon or mineral sectors, Kazakhstan’s most profitable industries, these being reserved for an inner circle around President Nazarbayev. At various points, the emergent capitalists of the second tier agitated for change and even formed opposition parties, though these efforts were rebuffed. Moreover, Nazarbayev demonstrated, several times, that the position of oligarchs in both tiers was dependent upon his personal patronage, even while he allocated oil wealth toward both strata of the elite to stave off potential destabilization (Isaacs 2008; Ostrowski 2009).

Borrowing the motif of the Asian tiger economies, Nazarbayev’s stated goal for Kazakhstan—to become a Central Asian “snow leopard”—from the beginning associated regime legitimacy with developmental ambition. Initially, these efforts looked toward the World Bank’s neoliberal narrative of development in the newly industrialized countries—published not long after Kazakhstan’s independence—as a blueprint, with the state’s role mainly being to prepare the ground for an effectively functioning market economy (World Bank 1993; Stark and Ahrens 2012).

However, with oil exports tied to Russian pipeline infrastructure and expansion of capacity dependent upon Western oil companies, Kazakhstani frustration with the inability to recoup revenue from extractive industries grew. Such feelings intensified in the early 2000s, as oil prices began to rise and huge new discoveries, such as the Kashagan Field (the largest outside West Asia), were made. A stronger bargaining position for the government prompted a reassertion of state participation through the stipulation of a minimum 50 percent share for oil parastatal KazMunaiGaz in joint ventures with foreign firms, as well as increasing attempts to broaden the range of investors as a means of reducing reliance upon any one Russian, Chinese, or Western firm (Domjan and Stone 2010).

A large proportion of hydrocarbon revenues was diverted toward a reorientation of the economy along a more state-led path, particularly following the 2008 financial crisis, though discerning between sincere developmental ambition and the need to allocate resources among supporters and potential enemies of the government is difficult. In many senses, this question may be somewhat moot, however. As with Sonangol in Angola, there appears to have been a recognition at the highest level of the state, if not among many individual members of the elite, that the best way to secure sufficient revenue for distribution of patronage was to run the main engine of accumulation/enrichment, the national oil company, according to commercial, profit-making principles (Franke, Gawrich, and Alakbarov 2009; Domjan and Stone 2010). While islands of efficiency may not extend much beyond Sonangol in Angola, there are some indications that, in Kazakhstan, other areas of the state may tend more toward the longer-term end of the accumulation–rent continuum. This is perhaps a reflection of a relatively stronger bureaucratic tradition, inherited from Soviet times, though, again, the lines between profit seeking and patronage seeking remained blurred over the whole period (Cummings and Nørgaard 2004).

Several sovereign wealth funds were set up during the boom years, including the National Oil Fund, which acts as a source of savings with which to stabilize the economy, and, most importantly, Samruk-Kazyna, which evolved from the unification of state holding companies into an apparent vehicle for development via government investments and loans and now manages $77.5 billion of assets (Grigoryan 2016).11 Samruk-Kazyna plays an important role in industrialization, diversification efforts, and infrastructure expansion and apparently has been modeled on the Singaporean sovereign wealth fund Temask, though with more of an active developmental function (Kemme 2012). However, Samruk-Kazyna also has been used to extend loans to failing companies owned by members of the elite—particularly during the post-2008 recession—and has been criticized for the politically motivated appointment of senior figures and for largesse in payment of bonuses in recent years (Peyrouse 2012). As in Angola, the state parlays its control of resource rents into a dual, not always contradictory role as both development actor and guarantor of a national network of elite patronage.

Conclusion

In several senses, Angola and Kazakhstan may appear to be little more than some of the latest additions to the extensive roll call of rentier states, with the size of their resource sectors, relative to the rest of the economy, resulting in political-economic structures distorted and dominated by the struggle for control and distribution of extractive rents. These dynamics are in no way unique to the commodity boom period and can equally be applied to a range of states across the global South and in a variety of eras. There are good reasons, however, to argue for the designation of the EO type as representing a distinct form of rentierism that would not have been possible without the China-led resource boom.

Many of the structural adjustment initiatives of the 1980s and 1990s were partly geared toward tackling the perceived problems of rent-seeking behavior particularly associated with rentier states (Evans 1989). Nevertheless, the proposed solution, of shrinking the size, reach, and power of the state apparatus, tended to simply shift the focus of rentierism rather than eradicating it. I discuss this phenomenon in more detail in chapter 8, where I show, for instance, that even in a case such as Zambia, where privatization of the copper industry removed the major source of rent from state control, distribution of patronage, now increasingly derived from aid flows, continued to drive the country’s political economy to a great extent, even if patronage networks now increasingly encompassed private as well as public office holders. In other cases, even during a neoliberal era of generally low prices and pressure to limit state participation in extraction, natural resource revenue was not dislodged from its position as the central source of rents. Neoliberalism, therefore, proved very much compatible with rentierism, even if dismantling state bureaucracies altered its institutional shell.

The circumstances of the commodity boom enabled the emergence of the particular form of rentierism seen in the EO type, which appears rather distinct from the kind of rentier state that would be expected under neoliberalism. While much of the developmentalist rhetoric emanating from the governments in Astana and Luanda was primarily intended to confer legitimacy upon the respective regimes, it also tended to draw from visions of economic transformation that ran contrary to neoliberal views. Similarly, although the ensuing development initiatives may have been vehicles for elite enrichment, these vehicles look rather different from those that would be expected under a regime seeking to appeal to neoliberal sensibilities. The leading role played by Sonangol in Angola, and increasingly by Samruk-Kazyna in Kazakhstan, gave a quasi state capitalist character to the functioning of both economies, in keeping with their economic priorities, which seemed to hark back to an older, modernization-inflected understanding of development.

The contrast between these features and the prevailing orthodoxy is particularly striking in the case of Angola. For all the World Bank’s renewed enthusiasm for infrastructure in recent years, it seems safe to say that most of the Angolan government’s major publicly funded schemes—the special economic zone, suburban housing development, airport construction, state-owned supermarkets, or the sheer scale of road and rail investment—would not have found their way into any Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper. This is not necessarily meant as praise of Angola’s development strategy; after all, there seems little evidence of even an attempt to improve the lives of the majority of the population. There is no doubt, however, that the conditions of the commodity boom allowed both Angola and Kazakhstan to assert policy autonomy, with sufficient fiscal resources to pursue strategies of their own making.