Chapter 8

Speaking Out in the Age of Trump Matters

The day after Trump was elected president was particularly difficult in the Thomas household.

The night of the election I started getting tired around my regular bedtime, which is shortly after the kids go to sleep. Watching the election results and the commentary had the same effect on me as the sound of ocean waves or a lullaby after some warm tea for me. I woke up in the middle of the night, rolled over to check my phone to see the updates, and I couldn’t believe my eyes. Donald Trump had won the election. I must have gasped because I woke up my wife who had been sound asleep, and she asked what was wrong. I told her and she replied, “Stop playing, that’s not even funny.” But she turned on the TV and it was confirmed: Donald Trump would soon be sworn in as the next president of the United States of America. We couldn’t move. I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I had to be having a bad dream, a nightmare. So after it finally set in, my wife and I asked each other a question that kept us up for the rest of the night: what were we going to tell the kids?

The next morning, there was an eerie atmosphere. We sat eleven-year-old Malcolm, nine-year-old Imani, and six-year-old Baby Sierra down at the breakfast table and we told them the election results. They too were in denial for quite some time. Imani and Baby Sierra said they were ready to move to Grenada, where my family is from. Malcolm just sat there in disbelief; his little heart was broken. Like when a kid finds out that there is no Santa Claus, or no tooth fairy, or that wrestling is fake. It’s like his whole entire world had turned upside down. He just kept repeating, “How could this happen, Daddy? There are that many racist people in the country? There are actually that many people who don’t like women and who don’t like Mexicans or Muslims or Black people? There are really that many people who agree with him and think that he would be a good president for us?” I told him apparently so.

Imani’s mind was made up: she told me to call the prime minister of Grenada (as if I could just ring him on his cell phone or something) and explain that we were ready to come home. She said it wouldn’t be safe for us here in the US. She had friends who were Latino—would it be safe for them here? Should they come to Grenada with us? Nichole was hugging them and trying to assure them that we were going to be okay, but her eyes betrayed her. I really couldn’t come up with any words to say at all. I had nothing. I was still in shock myself.

Malcolm said he was scared and didn’t feel safe, and that on the one hand he didn’t want to live here anymore, but on the other—and he paused before asking—“Would Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, or any of the people I have learned about run away, or would they stay and fight? I don’t want to give Trump this country, he doesn’t deserve this country.”

I told him that was a good point, then I said that Black people have survived much worse than Donald Trump, and we still made it. Malcolm said, “That’s right.” Nichole smiled and said she couldn’t argue with that at all.

Later that day, I discovered there were protests all over the country, on social media, in DC, New York, Chicago, LA. All over the country people were letting their voices be heard. And athletes were tweeting their disapproval of the election results. It was almost as if Trump’s victory was energizing everyone. Not long after, I asked ESPN commentator Michael Wilbon for his thoughts on athletes using their platforms to speak out against Trump.

Etan: Right now, athletes are speaking out more than we’ve seen since the 1960s. Do you think this is a good thing, or do you think athletes should pretty much stay in the lane of sports and athletics?

Michael Wilbon: No, I don’t ever believe in anybody staying in any type of a box. I think it’s absolutely incredible what I am seeing from athletes. I think there are many reasons that have ignited this surge of athletes speaking out. Two of them are the election and the relationship, or the lack thereof, between police and specifically young Black men. And you’re absolutely right—this is not new . . . But I think the difference is, there is less risk. I am old enough to have covered athletes when there was enormous risk. Where people would just shut you down completely, and I’m not talking about being at risk of losing your endorsement dollars, I mean being at risk of losing your career, your livelihood . . . We are blessed to live in a different world now. We are now in a time where we have more freedom, and I say “we” because I couldn’t have my job in the 1960s if I had written some of the things I wrote in the 1980s, so there is less risk for me as well.

Etan: Now, with current players speaking out against Trump, and many NBA CEOs being conservative Republicans, I would think there would still be a great deal of risk in speaking out.

Wilbon: Well, you know why I don’t think so is, for one, you have half the country speaking out against Trump, and in a case like Gregg Popovich, who is really in a place where few public figures in sports have dared to go, that’s something that didn’t happen thirty, fifty years ago . . . But it’s a different time. We saw entire basketball teams speak out against police violence, even with the WNBA situation. They initially wanted to punish the players and silence them but they couldn’t . . . The entire power dynamic is different now, and I’m sure that emboldens people.

Etan: Yeah, but it seems like sometimes you have the freedom to say it, but only as long as enough people agree with it. There are certain things that you still can and will be punished for.

Wilbon: Well, some protests are much more popular than others, there’s no doubt about that. But there are others that have direct penalties and others that will allow you to only be unpopular, but won’t cost you your job.

Etan: We have seen a surge in players speaking out about racism. Some players seem fearless: Jeremy Lin taking strong stances against racism and what he has been subjected to as an Asian American; Bradley Beal standing up for Black Lives Matter; Serena Williams taking a break in the middle of Wimbledon and tweeting, “In London I have to wake up to this. He was black, shot 4 times? When will something be done—no REALLY be done?!?!”

Wilbon: I am so glad that they are using their voices and I could do a complete section on each of the people you named. I was so happy to see Bradley Beal take the stance he took, especially me being here in DC and covering the Wizards. But let me talk about Serena. Look at the support she got from within the industry and outside of it—it was wildly effective. If Arthur Ashe did the same thing forty years ago in his heyday, would it have had the same effect? . . . There were other people who supported Serena in bringing that racism that she experienced to the forefront, and that was extremely important. Just as it was extremely important for Jeremy Lin to bring that racism to the forefront . . . When athletes like Lin and Serena take those stances, they are taking it for all of the people who don’t have the power they have to bring racism to the forefront.

So many athletes did just what Michael Wilbon is referring to: they took to social media to show their disapproval of Donald Trump, especially when he signed an executive order to suspend the entire US refugee admissions system and implement a Muslim ban. The executive order targeted seven Muslim-majority countries and looked to prevent individuals from those countries from entering the United States for ninety days. It suspended the US refugee program for 120 days and put an indefinite halt to all refugee intake from Syria. It even prevented quite a few legal US residents who were en route to the United States when Trump signed the executive order from entering when they landed. Several of those travelers were detained and others were deported back to the countries that they had flown in from. Thousands of people flocked to airports across the country to protest.

After the signing of the order, a number of athletes utilized their social media platforms to voice their disapproval. Los Angeles Laker Luol Deng told reporters:

I would not be where I am today if it weren’t for the opportunity to find refuge in a safe harbor. For the people of South Sudan, refugee resettlement has saved countless lives, just as it has for families all over the world escaping the depths of despair.

It’s important that we remember to humanize the experience of others. Refugees overcome immeasurable odds, relocate across the globe, and work hard to make the best of their newfound home. Refugees are productive members of society that want for their family just as you want for yours. I stand by all refugees and migrants, of all religions, just as I stand by the policies that have historically welcomed them.

Former NBA superstar Hakeem Olajuwon told reporters, “I’m a public figure. I’m a Muslim. We don’t have too many public figures that can really speak up. If I don’t, then I’m not taking my responsibility . . . We can’t exclude some people or countries. He can say it’s not against Islam, but really, indirectly, it is.”

The Major League Soccer Players Union issued the following statement:

We are deeply concerned, both specifically for our players who may be impacted, and more broadly for all people who will suffer as a result of the travel ban . . . We are extremely disappointed by the ban and feel strongly that it runs counter to the values of inclusiveness that define us as a nation. We are very proud of the constructive and measured manner in which [US men’s team captain] Michael Bradley expressed his feelings on the ban. It is our deepest hope that this type of strong and steady leadership will help to guide us through these difficult times.

I tried to show my son every time people were demonstrating or marching or protesting, and athletes were tweeting, and Malcolm’s reply was always the same: “Good, I hope everyone who has a voice continues to use it.”

I asked MSNBC’s Chris Hayes, host of The Chris Hayes Show, for his thoughts.

Etan: You’ve been supportive of athletes using their voice as a political platform. How important do you think it is, right now, for athletes to speak out?

Chris Hayes: Well, I think it’s always important, but I don’t think it’s any different from any other citizen. It’s important because citizenship is important, and civic society is important, and athletes are citizens; they are human beings; they are fellow members of the American political system. It’s particularly important, I think, because it’s not just a massive platform, but access to audiences that might not find their perspective. That, to me, is why it is so important, but it is also a very loaded topic.

A professional athlete has an access to a set of people watching him or her that is not defined by politics. Whereas the rest of media is increasingly organized around political lines. So if you’re LeBron or Dwyane Wade or Russell Westbrook or you’re Colin Kaepernick, and you’re giving a postgame press conference, the audience for that is not an audience defined by people’s politics . . . That’s actually what’s both so powerful and so explosive about it. Because people are coming to it because they want to see how their fantasy football players did. And they’re like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa . . .”

Etan: Right. So it’s kind of invading their space.

Hayes: That’s exactly right! Yeah, but that’s productive. One thing I struggle with is that it’s gotta go both ways also, in the sense of an athlete who’s a Trump supporter has every right to express their ideas and thoughts and opinions as an athlete who is not. Because people are selective, where they’ll be like, “Oh, I’m glad you’re speaking out,” when you agree with me, but it’s like, “Oh, you’re an athlete, why do I want to hear what you have to say?” when they don’t agree. You can’t do that. It has to go both ways.

Etan: Nobody is disagreeing with the athlete speaking out about domestic violence. But anytime you’re dealing with a more divisive topic, whether it’s Mike Brown or Trayvon Martin or Trump, that’s where there’s an issue. But from an athlete’s perspective, you have to know that when you do speak out, some will agree with you, some will vehemently disagree with you, and that’s okay.

Hayes: Oh no, that’s fine. I just feel like people need to check themselves, myself included. If an athlete is speaking out in a way that you don’t agree, there’s that instinct to be like, “Well, what the hell do you know?” (Laughter) But if they speak about a thing you do agree on, there’s an instinct to be like . . . (clapping), but you gotta be consistent.

I do think there’s a particularity around race. Because the racial dynamics of sports performance and fandom are so complex, and loaded, and now I think it’s part of the other thing that’s so profound and powerful, particularly around issues of race: that Black athletes have an access to a white audience to be able to talk to them about the experience of race that very few others will have or ever have . . .

I think the politics of sports are interesting, and sports is such a massive part of our public life . . . It’s like Silicon Valley isn’t “politics,” but there’s a lot of politics about what goes on in Silicon Valley. You can’t understand Silicon Valley without understanding politics. Politics are what shapes the structure of those markets, the structure of how things get raised, the perception. The same thing is true with sports, and in some ways sports occupies even a bigger part of our mental landscape.

Me and Chris Hayes after an interview. He always enjoys talking sports and politics with me.

Etan: When the New England Patriots visited the White House on April 19, 2017, after winning the Super Bowl, many athletes chose not to attend. How strong of a message does that send, or do you think this is less about social justice and more about Trump himself?

Hayes: Yeah, I mean in some places, Trump is the polarizing thing. It’s not just sports.

Etan: So it seems like you’re forced to have an opinion about it even if you’re not into politics.

Hayes: Totally, yes. Agreed. But now I’m going to go and walk on the other side and argue against myself.

Etan: Okay, go ahead.

Hayes: The country is increasingly polarized. That’s a brute fact. This is diagnosed in a hundred different ways . . . Like what kind of restaurant you eat at. Like where you live, urban or rural. And the thing that I will say that I like about sports, I do like the fact that I find myself talking to someone who I don’t share political views with, where we can discuss sports.

There’s something amazing in a landscape of America in which people are so polarized. There is this pressure-valve thing . . . I can talk the playoffs or the Cubs or whatever, with anyone, across any political perspective.

And a really interesting moment in the culture right now is whether sports becomes something increasingly like other parts of culture. In terms of that polarization. And I’m not saying it’s good or bad, I’m just saying that’s a question right now . . . Can sports preserve that in the face of an increasingly polarized America?

Etan: Okay, let’s say you have somebody who is an avid Trump supporter and you’re talking to them about the playoffs. Are you saying that can provide some common ground? In hopes of moving toward some type of growth or something positive?

Hayes: Yeah. In fact, that’s the power that particularly athletes hold: to have the ability to move people. And I’m actually more curious about what you think about this.

Etan: I’m supposed to be interviewing you, Chris (laughing).

Hayes: I know, but unfortunately, I don’t get a chance to talk about this as much as I would like . . . but when you have really high-profile examples of athletes coming out on political issues, I feel like most of the coverage tends to focus on the backlash, right? . . . But I was wondering about the people who aren’t being loudly backlashy. I always wonder if it’s penetrating them. And you’ll see these sort of interesting defenses from people . . . You’ll see someone come and defend Colin Kaepernick and you’ll be like, I am absolutely shocked that you of all people would be a person to defend Colin Kaepernick.

Etan: That’s a good point. Because there was definitely some unexpected support that I saw, though it also worked the opposite way as well. Even with certain members of the Patriots choosing not to go to the White House because of Trump, you saw some people vehemently objecting to that, using words like anti-American and anti-police.

Hayes: So, Kaepernick took a stance that was this really admirably conscientious private gesture. And the response was, “Oh, you’re an attention hog.” And it’s like . . . he was just doing this thing as his expression of conscience. But other people made it this big thing and then obviously it went from there. What’s amazing about it is just the platform. And you were absolutely right when you said it’s like you are invading people’s safe space. You are forcing people, in a part of American life, where they’re not thinking about politics, to think about politics.

Etan: As you know, I grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. I’m looking at some of the Trump rallies, and I’m looking at the same people who I went to school with on Facebook. And they are these avid Trump supporters. Or I think of fans who are filling up the arenas, going to the Oklahoma City Thunder games, then going to the Trump supporters’ rally. So then there’s this dynamic where you think, Okay, it’s not quite transferring. You see me and love me and cheer for me on the court, but as soon as the game is over, you put on your Make America Great Again hat and go talk about building a wall?

Hayes: I think that’s what’s so powerful, right? I mean, the thing that you can’t escape in all this is race and the centrality of it . . . But the racial dynamics of fandom are really complicated. Like the racial dynamics of white fandom. For many white people, the most intense focus and attention they have on a Black person is an athlete. For a lot of people, particularly for men of a certain age. Like if you’re a fifty-five-year-old white man in Oklahoma and you’re a Thunder fan, you’re invested in Russell Westbrook in a way that’s like really, fascinatingly, psychologically fraught.

Etan: No question. So you feel love and admiration toward Russell Westbrook, then Terence Crutcher is murdered in Tulsa and you feel nothing.

Hayes: But even when that happened to Thabo Sefolosha, no one did anything. That’s what’s so fascinating. I was surprised that moment wasn’t bigger for that reason. Where I sort of feel like, even at the pure level of fandom, just apolitical fandom, you broke my dude’s leg. He was going to play for us and you took him out of the playoffs. And I was surprised that was not a bigger thing.

Etan: Why do you think that is?

Hayes: I think because sports coverage is still conditioned to be resistant about letting those issues in. They don’t know how to deal with it and it’s like the police say, “Well, he was being unruly,” or whatever they said about Thabo.

Etan: “Resisting arrest.”

Hayes: “Resisting arrest,” which is just like the first excuse or justification that is always given in any case . . . But it’s like there’s just this fear of wading into the thicket of that. Although that’s changed a little, but it still has a long way to go as we saw with the coverage of Thabo Sefolosha.

Etan: It has a very, very long way to go, but the reason we are seeing any change at all is because of the athletes in particular. It’s like they’re forcing people to talk about it. So before, the CEO of Under Armour came out and supported Trump. Now Steph Curry, Misty Copeland, and the Rock—three of the most high-profile people sponsored by Under Armour—came out and said, “No, we do not support this.” They were very clear about their position and then you saw the CEO completely backtrack on his statement. You know what I mean?

Hayes: That’s power.

Etan: It’s power. So the fact that more athletes, right now, are using that power, I don’t know if we have ever seen this. We can go back to the sixties, but even then, it was a select few.

Hayes: Oh, it’s more than I’ve ever seen in my lifetime . . . There is no question that athletes have been more outspoken, committed, and public on controversial political issues.

Etan: I just hope it continues to grow.

Hayes: Why do you think that’s changed? Because I feel like when you were playing, you were like a real outlier in a way that if I put you on a team right now . . .

Etan: It would almost be the norm—almost.

Hayes: It wouldn’t be the norm, but it would be closer to the norm than when you played. Because when you played it was like, “Whoooaaaa, he’s talking about Iraq? He’s talking about President Bush?” And not just lightly talking about it, but breaking it down to particulars and verbalizing those particulars in a way that I personally had never really heard an athlete do.

Etan: I think people are more aware now. I don’t want to say things have gotten so much worse, but with Trump, you’ve got to say that people are more aware of how bad it is. A lot of that may have to do with social media as well. You had police brutality before, but now everybody is seeing it on video. Then they are seeing cops get away with it. So that is pushing guys to speak out who have never spoken out before. It’s a beautiful thing to see so many young athletes using that power because it forces people to have conversations and deal with things that they don’t want to deal with in their sports arena.

Hayes: Absolutely. That’s 100 percent true.

Etan: So why do you think people don’t want to deal with this so much in their sports arena?

Hayes: I think there’s two reasons. One is it creates a weird, uncomfortable fan/athlete relationship. If a person’s saying something that you don’t agree with, it instantly complicates the emotional experience of fandom. So for me, my example of this is Jake Arrieta. Jake Arrieta is like stud star pitcher for the Cubs. I’m a huge Cubs fan, I am massively invested in Jake Arrieta’s performance. I always sort of suspected his politics were conservative ’cause he’s like a good ol’ boy, he’s from Texas . . . He tweeted after Trump was elected, “Time for Hollywood to pony up and head for the border #illhelpyoupack #beatit.”

Etan: That ruined it for you.

Hayes: Right! Like all of a sudden, the emotional relationship that I had with this person, who’s a complete stranger to me by the way . . . I just project, which is the experience of fandom, I project all this emotional investment and all of a sudden I was like, Uhhhhhh, what a bummer.

Etan: Right.

Hayes: It’s like the experience of fandom is bizarre, irrational, childlike in its emotional simplicity . . . Then another part of it, particularly when the issues are front and center of race, which I think have been the most kinetic, explosive, dominant in this era . . . I think part of it is just like white resistance to talking about race and dealing with racial inequality and wanting and feeling like, I don’t want to hear about it, or resistance or feeling like they are being attacked or they are being guilt-tripped for all these things, which shows up in other domains but is particularly intense in the very racially fraught experience of white fandom with Black athletes.

So I think it’s those two things together. Which I think applies in different directions. Do I wish Arrieta had not tweeted that? Yes, and then I think there’s a more profound kind of social justice point, the particular nature of white fandom and Black athletes and this sort of pretty messed-up kind of . . . thing that a lot of white fans want, which is like, “I want to root for you but I don’t want to see the larger racial context of your life and your existence. Just shut up about that.”

Etan: Interesting. I also interviewed Craig Hodges, who talked about his experience with the Chicago Bulls after he wrote the letter to the older Bush. A lot of fans turned on him. He was the three-time three-point champion. He had one of the highest three-point percentages in the NBA, but everybody looked at him differently now because they knew what he thought.

Hayes: Right. And in some ways . . . there’s a certain undo-ability to that. Like I can never go back to the world in which I don’t know that Jake Arrieta feels this way. It’s like forever . . . But again, that’s one hundred times more loaded in the context of “white fans, Black athletes” issues of racial justice.

Etan: Keep going with that. Say specifically what you mean by “loaded.”

Hayes: It’s loaded for the athletes in terms of the wrath that they can incur. It’s loaded for the fans because they feel like some part of the edifice they built around their understanding of race is being challenged or they are being guilt-tripped.

Etan: Then you have someone like Trump, who is polarizing on racial issues, but in the opposite direction. That makes people uncomfortable too.

Hayes: Yes, it definitely does. I do think that Trump is definitely polarizing, but also so polarizing in sort of demographically predictable ways. When you’re looking at the New York Knicks, what did Trump get of the share of die-hard New York Knicks folks? Not that much . . . What did he get of the die-hard Chicago Bulls fans? Not that much. Right? . . . I think in a weird way, because he’s so polarizing and because that polarization has been forced into so many parts of life, it’s made it safer for athletes to come out.

Etan: I agree.

Hayes: It’s like, well, everyone’s choosing sides and everyone’s sort of out there about this thing and no one’s going to pretend that this huge polarizing event didn’t happen in American life. So I’m not going to pretend either. And then, also, if I happen to be in a market, I’m not saying that athletes are calculating, because I don’t think they are, but I also think it’s a case of, if you come out against Trump while you’re a starter for the New York Knicks, I don’t think you’ve really hurt yourself.

Etan: Okay, but then you have somebody like Gregg Popovich, who coaches in San Antonio, Texas. He hasn’t really experienced a lot of backlash, but then there’s a different racial dynamic since he’s not Black.

Hayes: Yeah, I totally agree, although I also think it’s like the same thing with Kerr. Like Kerr’s a better example. Curry and Kerr, they’re in the East Bay.

Etan: Right. They’re different, but Popovich is in Texas and Cuban is in Texas and that’s a little bit different, and they’re also white men speaking out.

Hayes: Exactly, and they haven’t gotten that same, “Why does anyone want to hear what you have to say?” Or the, “You’re just an athlete so shut up and play basketball.”

Etan: Let me ask you this, though. If they were both Black—if Popovich was a Black head coach and Mark Cuban was a Black CEO—would the reaction have been different?

Hayes: Hmm, good question. I think it would be. I think it always is . . . I do think the Popovich thing is a fascinating case study ’cause I was kind of blown away that he said that. I was like, Whoa, dude.

Etan: I was too, and I was waiting for the backlash.

Hayes: And I was waiting for the backlash too. I also sort of always assumed coaches are conservatives.

Etan: Especially in the NFL. The NFL is different than the NBA.

Hayes: I would be curious what you think. I also think there’s just a huge difference, to me, in the politics of the leagues.

Etan: The NBA versus the NFL? Completely. Night and day. Not even close.

Hayes: The NBA appears to be a much more liberal league as a whole. There’s a certain raw demographic nature of the fact that the NBA is a Black league. African Americans in America are more liberal than white people, on the whole, on average. Ergo, it’s a more liberal league.

Etan: What are the percentages of Black people in the NFL, though? It’s not a “Black league” but the percentage is pretty high.

Hayes: It’s pretty high. The other thing to think about is that as leagues get less white, how do they manage the politics of that? Because my feeling about the NBA is so defined by these sort of . . . There was the Magic-Bird era, which is this perfect rivalry for the league to promote, both because they’re incredible players but also one’s white, one’s Black.

Etan: And they’re friends.

Hayes: They’re friends. One’s from, you know, one plays out west, one plays in the Northeast. It was so perfect. It was like this perfectly representative thing of what they wanted. Then you get the Jordan era and Jordan achieves this level of apolitical stardom because he chose to be apolitical—that’s incredibly transcendent across racial lines because he chooses to sublimate anything that would threaten that, right?

Etan: Right.

Hayes: The point of politics in the league is the fight in Auburn Hills. The Pacers-Detroit fight.

Etan: Of course, the “Brawl in the Palace.”

Hayes: Which is where all of the ugly subtext about white fandom comes out.

Etan: The fear.

Hayes: The fear. Thugs, all this stuff. The fact that they actually swung at fans. It was just like the worst nightmare from a management perspective. And that’s the point where you see the league in its conception and projection, to me, take a kind of right-wing turn. Like that’s when the dress code comes in . . . the idea of, we need to make these athletes less threatening from a marketing perspective. I remember you writing at length about this topic and you were spot on. There’s also the Latrell Sprewell incident too, which was a Black man choking a white coach; that’s when the league got into this very kind of reactionary Black-lash place, and then I think, for whatever reason, they started to come out of that in the last eight years . . . The league, to me, got less reactionary and more progressive over, say, the last eight years.

Etan: As far as what in particular?

Hayes: The messages it’s sending, the tenor of its public service announcements, its relationship to American politics in terms of the outspokenness of its players . . . From 2004 to like 2011, there’s this kind of reactionary turn. Three things happen in that era. There’s [Allen Iverson] and the crazy challenge that A.I. is to the league’s image because he’s . . . so unapologetically Black. Everything about his game, the cornrows, the way he’s perceived, he records a hip-hop album. The Latrell Sprewell coaching incident, the “Brawl in the Palace.” That period . . . you can feel the league feeling a crisis about its management of how it’s selling “Blackness” as nonthreatening to its white fans.

My question to you is, what happened?

Etan: So what I saw happen was, you had the Trayvon Martin murder. Then you had Eric Garner’s murder. Then you had Michael Brown’s murder. Then you had Trump elected. I think that’s what happened.

Hayes: So you think it’s just like society was driving consciousness among the athletes, who then pushed the league in a direction?

Etan: That’s exactly what I think. What do you think?

Hayes: Yeah, I think that’s right. I also wonder . . . I’m just curious about the demographics of the league’s fandom . . . because the thing about basketball is it’s all about economics, as is all sports. And the people that spend money on NBA league pass packages, jerseys, they’re majority white but disproportionately Black. Right? So the league’s fandom, the people it’s marketing to, are a greater share of African Americans than the American populace. And I wonder how much of the “progressiveness” is simply because they recognize their fan base.

Etan: There’s no question. Because you look at the difference in the NBA and NFL. The NFL is completely different—I don’t think they would have embraced some of the activism we saw in the NBA. Can you imagine if all the NFL players wore I Can’t Breathe jerseys?

Hayes: They’d go crazy. But you think that’s also about the fan base?

Etan: I’m not sure if it’s the fan base. I think the powers-that-be in the NFL are a lot more conservative. So it just kind of trickles down.

Hayes: Right.

Etan: So . . . there’s a little bit of suppression of athletes speaking out in a way that you don’t really see in the NBA.

Hayes: Yeah. That’s definitely how it feels.

Etan: Because LeBron doesn’t get the backlash that Kaepernick gets.

Hayes: No.

Etan: LeBron has done a lot and said a lot of the same things that Kaepernick has said, but the backlash is completely different. I think that’s just the way it is.

Interview with Alonzo Mourning

Back in high school and college, if anybody asked me what type of player that I wanted to play like, I would immediately say Alonzo Mourning. When I saw him transform his body from his early years at Georgetown to his years with the Miami Heat, where he at times almost resembled an action figure, it made me get in the weight room. His power jump hook to the middle of the lane. His sweep to the middle, then spin to the baseline. The way he blocked shots, the physicality and intensity he played with, and how hard he worked on the court. In fact, one of the reasons I wore 33 at Syracuse was because of Alonzo Mourning.

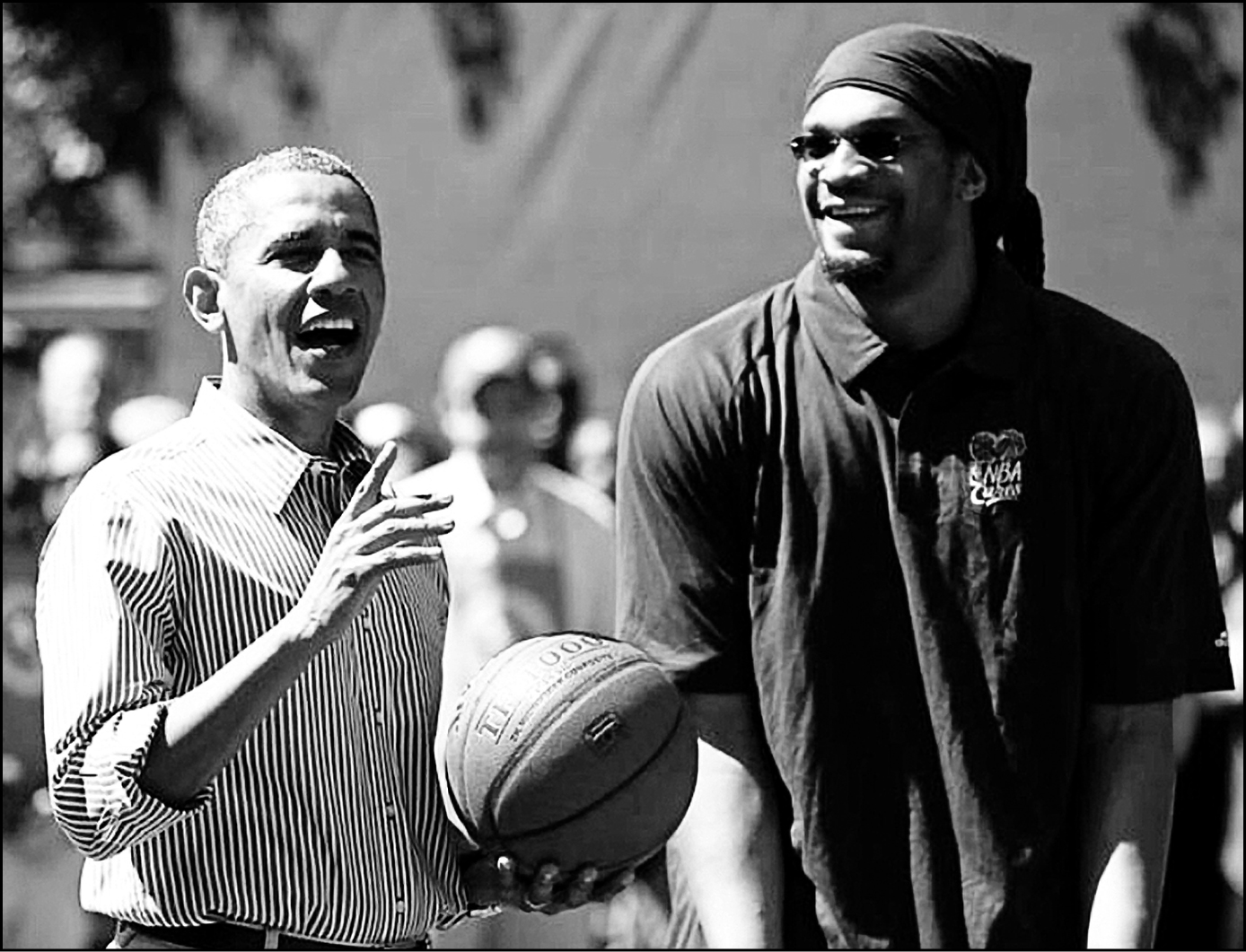

Another thing I noticed about Alonzo Mourning was how much work he did in the community—his activism, and his willingness to take a stand on different issues. It was an honor to serve with him as a “surrogate” for President Obama during both terms. As a surrogate, I campaigned on the president’s behalf: I woud appear at rallies performing spoken word or giving speeches; and I participated in debates and political discussions on MSNBC and at various events in DC. Alonzo would engage in other types of activities, such as hosting campaign fund-raisers in Miami. I would support Alonzo’s events and he would support mine. He has sat on a few of my panel discussions, including the Black Lives Matter program we did during All-Star Weekend 2015 in Harlem.

Alonzo is a great example of an athlete who took his education seriously, wasn’t afraid to speak out, and has used basketball to open doors to change.

Me and President Obama shooting hoops at the Easter Egg Roll. It was an honor being a surrogate for the Obama administration, participating in his fatherhood initiative, and working with My Brother's Keeper.

Etan: What led to your decision to throw your full support behind President Obama?

Alonzo Mourning: When I saw the opportunity and the potential he had, and the overall way he communicated to the American people, that drew me to understand that this brother is going to need all of the support he can possibly get to become the commander in chief. So when I had the opportunity to support him, I jumped at that opportunity. He is a huge basketball fan as everybody knows, and through the up-close-and-personal interactions that we did have, we developed a brotherly type of relationship and it was genuine. We shot around on the court . . . We developed the type of relationship that allowed me to continue to support him on his journey and utilize that camaraderie to build bridges. He had a dedication to helping boys and young men of color, and by serving on his initiatives and boards like My Brother’s Keeper and the President’s Counsel on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition, which was very near and dear to my heart . . . And as his term progressed, and he won the presidency and his responsibilities increased, it became more and more evident that there were forces who did not want to see him succeed, which made me want to support him even more.

Etan: You live in Florida, a state that often goes “red” in presidential elections. Did you ever fear the blowback for your support of President Obama?

Mourning: I wasn’t concerned with anybody else’s opinion in any way, shape, or form . . . I did what I thought was right and I chose to support a man who was on the right side of right. Yes, he was the first African American president . . . but if he wasn’t on the right side of right, he wouldn’t have received my support. I closely examined the candidates that he was up against . . . but there was a genuineness behind President Obama in his understanding and caring about the American people, and that’s what set him apart. You could hear it in his speeches of how he laid out the plans for us to be a better nation . . . It wasn’t about color; it was about service and doing the right thing for our country as a whole, inclusive of everybody. And I think during his terms he did a phenomenal job, especially considering what he inherited and the opposition he received throughout his entire presidency. No other presidency in history experienced the level of disrespect and opposition that he experienced. No one. But he never turned bitter. When they went low, he went high, like First Lady Michelle Obama said. And they represented themselves with nothing but grace and class.

Etan: There were probably more athletes who actively supported President Obama than any other president in history.

Mourning: That definitely didn’t surprise me. The way he communicated to the American people and the way he articulated his message helped us understand the genuineness behind his purpose and reason in wanting to become the president of the United States. That drew athletes to want to support him.

Etan: Now, with the Trump administration, the opposite is happening. We are seeing an unprecedented number of athletes and management speaking out against the president.

Mourning: The one thing about our political system is that everyone has their own different values and different opinions of how they see our country. And based on those different perspectives, each elected official is put into those positions to make decisions to serve the public, and unfortunately, it is very apparent that not everybody has those intentions. Some people speak a certain rhetoric that encourages people to vote for them and to put them in that particular position, but when they get there, their words are simply not genuine and their hidden agendas become revealed. Hearing the messages from the Trump administration, it is quite disheartening. There are not a lot of facts that are being expressed; instead, there are a lot of untruths . . . So of course you will have a lot of people, not just athletes, who object to those messages and the rhetoric, the untruths.

Etan: You do a lot of work in the community, especially through the Mourning Family Foundation and the Overtown Youth Center. In this Trump era, what is your direct message to the youth?

Mourning: To first of all do your homework. We live in a world that is dominated by technology. You are able to find the truth. Don’t just believe what you hear on television, or what you hear people say on social media, but actually do your homework and educate yourself about what is going on and the rules of the game. There is a reason why the current administration put a gag order on our environmental agencies. Because they speak the truth . . . Think about it right now: as we speak, our executive government is actually putting a gag order on our environmental agencies, and that’s a problem. That’s a huge red flag. That has never happened in the history of the United States. So that should send you the signal or raise your curiosity as to what they are hiding . . .

Etan: So you are basically telling them to arm themselves with knowledge to combat the hidden and many times not-so-hidden agendas of this current administration?

Mourning: The easiest way to control somebody is to keep them uneducated . . . They made it illegal for us to be educated during slavery. It was against the law . . . That’s why we had to sneak in churches and act like we were just having Sunday-morning church service—because our ancestors knew the power of being educated. And just as it was crucial then, it is crucial now. Education is the only way for you to be an active participant; you have to educate yourself on what is going on. So, for instance, when you don’t vote, that’s a problem. Educate yourself on, first of all, why you have the right to vote, educate yourself on the sacrifices that other people have made way before you even existed . . . Then you will understand the reason behind your vote, and that’s just one example.

Etan: What would be your advice to other athletes?

Mourning: When you think of the stage we have, the presence we have on social media and with the media in general, when an athlete says something, people hear it. Doesn’t mean they agree with it, but they hear it. They are exposed to it . . . We live in a society where everyone wants to follow but people don’t want to lead. The way you become a leader is you create a positive movement that everybody can attach themselves to with the goal of making a difference in other people’s lives. When you do that, it will become infectious . . . We as athletes have to realize how much power we have.

Interview with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

I remember my mother giving me a VHS cas about Kareem Abdul-Jabbar called, Kareem: Reflections from Inside. I must have watched it a million times. And my grandfather always had a tremendous amount of respect for Kareem, going back to his days at Kareem’s Power Memorial Academy in New York City. My grandfather always said that the sky hook was a shot that more people should utilize, including myself, but he also always talked about Kareem’s intelligence. Different books that he had written, and projects that he has been involved with.

When I took my grandfather to meet Kareem, he immediately began asking the legend about people from the playground back in the “Rucker Park heyday.” He thanked Kareem for being a great example for his grandson to follow, in how he was never afraid to stand up for what he believed and how he valued his education and pursued his writing and all of his other talents. It was an honor to interview Kareem for this book, and an honor that he was eager to be a part of it.

Etan: You of course have been on the Mount Rushmore of athlete-activists since your days at UCLA, but in the contemporary matters of police shootings and President Trump, how crucial is it for athletes to continue to let their voices be heard?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I think that anyone who is concerned with his/her community should be involved. It doesn’t matter if you’re an athlete or not . . . I understand the tremendous platform that athletes have, but sometimes regular everyday concerned citizens have a tendency to sit back and expect someone else to speak out or take a stand. We don’t want to put it all on the shoulders of athletes and entertainers . . . This is America. The First Amendment gives you the right to speak out on issues that you feel are important, and you should not hesitate to do that. Now, back to your specific question: all athletes have that right, and their additional status as athletes will make their platform bigger and enable them to reach more people on their platform and gain more attention, and it is my belief that they should definitely continue to do so in a positive way.

Etan: How do you feel about the people who go out of their way to tell athletes to just shut up and play?

Abdul-Jabbar: Pay them absolutely no attention at all. Nobody has the right to tell you what you can or cannot or should not be involved in. Athletes are no different from any other person. If you are concerned about something and you have a platform, then use it. The reason why those people focus on athletes is because their additional status in their community, among their peers, fans, and the entire country, means they have power and can really influence people. And of course just think of it logically: if you have someone with that type of power and influence, pushing for something you don’t agree with, of course they are going to try to do whatever they can to silence them, because they are a threat to them . . . But athletes should definitely never shy away from their power, but rather recognize and embrace their capabilities. Look at what happened at the University of Missouri. The football team made a statement and the people on campus had to listen. They had that much power. Now, they should always use that power wisely, but that power is there.

Etan: You recently expressed a “rage of betrayal” that you felt from the election results, which seemed to roll back progress for people of color in America. You also stated that the country will find it difficult to make this transition if society “embraces the leadership of a racist.” How do you see us as a country surviving the Trump presidency?

Abdul-Jabbar: Well, that’s a tough question. I can’t predict what is going to happen. I definitely don’t want people hanging on my words thinking that I have some answers that I don’t have. But I will tell you this: unless we get together and organize politically, whatever answers we do come up with won’t be listened to. I think that is the most important issue here. President Obama said it very clearly: “Don’t boo, vote.” That means you have to organize, you have to understand what the issues are and vote with the people who agree with you in how to achieve progress. One thing that everyone really woke up to when Mr. Trump was elected was there was too much apathy, too many people said, “Well, the people who vote will take care of it.” Well, your vote was missing, and your vote would have made a difference in that election. So we have to change that.

Etan: What was your reaction when you heard about the Muslim ban?

Abdul-Jabbar: Well, anytime that one group is singled out, that’s an alarm. Just think about this logically, and historically: if one group is being singled out, subjected to sanctions, pointed at as the cause of problems, or thought of to need extra vetting or to be an overall threat to the well-being of the larger society . . . it’s only a matter of time before the finger will be pointed at your group as well. This is a slowly creeping situation. I am glad that the system of checks and balances stepped on Mr. Trump’s toes and made that an impossibility. But we have to be careful here. We are starting to regress . . . and that’s really what we have to avoid. We are looking at a blatant attempt to erode all of the progress we have made over these last eight years, and that’s not to say that President Obama was perfect or all of his policies were perfect, but there was a lot that we accomplished as a whole under his two terms, and it’s sad to see that so much of that is being undone with the swipe of a pen . . . This is a tragedy and we have to combat it with all of our ability and all of our strength. And we have to do this together: Black, white, Christian, Muslim, male, female. We all have a common problem, and we have to come together to fight against this common problem.

Etan: How would you advise young people to get involved?

Abdul-Jabbar: They should use whatever means they have to get people out to vote. The whole “Get Out the Vote” campaign—that takes money, you know. One thing that we are sadly lacking is the financial wherewithal to become active politically. When we do not vote, our voice is diminished. That’s how we increase our voice. And we have to increase our organizational capacity so that we can go out and vote and make our political power known.

Trump’s plan involves scaring voters with a constant barrage of lies and exaggerations. The fact that this propaganda is so effective is especially sad, because the nation that once stood up to bullies like Hitler, Castro, and Khrushchev is now falling into goose-step behind a homegrown bully who seems afraid of everything that isn’t part of his entitled life, who responds to his irrational fears the way a child does.

There is a reason that the administration continuously attacks the news media—because if they can continuously create doubts in the minds of the average person who is too lazy to read and educate themselves on these issues, they’ll be incorrectly informed . . . People have to get to the point where they are not gullible. But, of course, that may be wishful thinking.

Etan: Another aspect of the current administration that has brought many athletes out is Trump’s misogyny. We saw a massive women’s protest all across the country . . . Talk about the importance of not only female athletes but also male athletes continuing to speak out against the sexism coming from the Trump administration.

Abdul-Jabbar: It’s an indication of how they view women and the status they want to keep. We have to educate people and the women have to organize. If you look at some of the polls, so many women actually voted for Trump and helped put him in office, which I definitely had a hard time and I still have a hard time comprehending. They actually voted against their best interest. They are either naive or ignorant to exactly what his intentions were and what his history was. But I don’t see how they could be ignorant to that fact, because it was broadcasted so much prior to the election, so I am just as befuddled on that one as anyone else. We have to inform people and inform voters. But it’s not just women who voted against their own interest. Many people . . . are now getting a rude awakening as they discover who he is and the direction he is taking us. We all should be very, very concerned about that.

Etan: Were you as surprised as I was to see some Black faces in the sports world standing next to Trump, urging other people to support him?

Abdul-Jabbar: Nothing really surprised me, Etan. Anytime someone like that can win the nomination, you know that there is a lot more to it than meets the eye. There is a lot of nostalgia for the good ol’ days, right after World War II and thereabouts, where the people who controlled everything politically and economically were very comfortable. And that’s changed a lot since then, and Trump brings back a nostalgia for that . . . So we have to be fully aware of what’s going on and do our due diligence before we support anyone or allow ourselves to be used in that manner. We can’t be puppets. We have to be educated, informed, knowledgeable people who can in turn use our platform and our powers for good, not allow ourselves to be used or exploited or taken advantage of for a photo op and used for evil. I can’t belabor the point enough that the vote counts, and is of the utmost importance. And we have to be very careful of who we align ourselves with.

Etan: How do you feel about seeing young athletes being as involved as they are these days?

Abdul-Jabbar: I know that the young athletes are noticing what has been going on and they are alarmed. And I’m glad to see that they are paying attention and they are doing something about it. Just the fact that they are calling attention to what the issues are is helping. When athletes speak out, it creates an immediate dialogue . . . When a prominent athletes takes a stand, he is going to shed light on that topic and people are going to start talking about it . . . You can’t change people’s minds if people don’t discuss the issues. They may see something or hear a point of view that they never would have imagined. And sometimes they can’t hear that from other political figures because the political line in the sand has been drawn . . .

But most, most important, and I know I have repeated this like a broken record, but I am going to end with this: we have to get out and vote and athletes have to use their platforms to urge the masses to get out and vote . . . We can’t complain after the fact, and have voter turnouts as low as they are. Youth voter turnout is consistently lower than the older generation . . . And not just the presidential elections, but local elections—the elections that decide who the mayor will be, who the police chief will be, who the local officials will be that directly impact their everyday lives. We have to keep encouraging the masses to vote so that we don’t allow a catastrophe like Mr. Trump to ever happen again.