3

‘A Small but Individual Name’: April 1910–May 1912

(i) Editors, publishers and printers

Lawrence’s movement between Jessie, Helen Corke and Alice Dax necessarily shapes our understanding of one aspect of his emotional turmoil during 1910; it is important, however, that we set this alongside the great strides he made in his writing, and the development in his understanding of the literary marketplace. On 25 April Lawrence received a response from Sydney Pawling to the revised manuscript of ‘Nethermere’. Pawling was evidently disappointed that more material had not been cut from the novel, but Lawrence was quick to defend its length and construction: he replied that he would ‘delete as much as I can in phrases and perhaps here and there a paragraph from the proofs, but there are now no passages of any length that I could take out’ (1L 159). Negotiations for the novel’s publication progressed smoothly: on 1 June he reported to Helen Corke that ‘Heinemann was very nice: doesn’t want me to alter anything.’ He signed a contract which gave him 15% royalties on normal sales; he also committed himself to offering Heinemann his next novel.

The experience of dealing with editors and publishers was not something that Lawrence relished, however: he declared that the ‘transacting of literary business’ made him ‘sick’ (1L 161). His subsequent correspondence with Frederick Atkinson, a reader for Heinemann, to establish a new title for ‘Nethermere’ illustrates Lawrence’s impatience with the processes involved in publishing, and his naivety concerning the marketing of his writing to a particular readership. In three letters spanning a whole month he suggested a range of options, including ‘The Talent in the Napkin’, ‘The Talent, the Beggar and the Box’, ‘Tendril Outreach’ and ‘Crab-apples’ (1L 163, 167, 169). He admitted that he was ‘no good’ at titles (1L 166). When Atkinson finally settled on Lawrence’s idea of ‘The White Peacock’, it seems to have been against the author’s own inclination.1

Further irritation was inevitable in his dealings with the English Review. Austin Harrison had contacted Lawrence in January to secure his services as a future contributor, and Lawrence agreed to continue sending work to the journal.2 By early March, however, he was complaining that Harrison had chosen to publish five of his poems against his wishes: they appeared as a sequence entitled ‘Night Songs’ the following month.3 Worse was to follow: although ‘Goose Fair’ was published in the February number of the journal, ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’ was held up by the backlog of contributions that Harrison had inherited from Hueffer. Proofs were produced in March 1910, but the story would not appear in the English Review until June 1911,4 by which time Lawrence had extensively revised it, the published version incorporating three distinct layers of corrections, cuts and additions.5

‘The Saga of Siegmund’ also gave Lawrence cause for concern. After its completion in early August he decided to send it to Hueffer before forwarding it to Sydney Pawling at Heinemann. There was no family holiday that year, since money was in short supply (the Eastwood miners had come out on strike in June; Lawrence’s father was working reduced hours, so the family relied upon contributions from Lawrence and Ada). Instead, Lawrence went away with his friend George Neville for a week in Blackpool from 6 to 13 August. They stayed in a boarding-house close to the North Pier owned by one of Neville’s relatives; they evidently enjoyed their stay, having fun at the expense of their fellow guests and flirting with some girls. Lawrence took a special interest in a young woman from Yorkshire. Towards the end of the week, he travelled with Neville to Barrow-in-Furness to visit an old college friend, Nina Stewart.6 However, when he returned to the Midlands, intending to fetch his mother back from Leicester, where she was visiting her sister and brother-in-law, Ada and Fritz Krenkow, he received some devastating news: she had been taken seriously ill during her visit. Lawrence wrote to tell Willie Hopkin that ‘a tumour or something has developed in her abdomen’ (1L 176); a doctor who was a close friend of the Krenkows diagnosed it as a cancer. Lawrence was forced to return to Croydon for the start of the new school year at the end of August. The proofs of The White Peacock finally arrived at the same time. He travelled back to Leicester on the first Sunday of the new term, 4 September, to check on his mother, only to find that her health was deteriorating. Back at Colworth Road he set to work correcting one set of proofs for Heinemann and sent the other on in batches to Louie Burrows in Quorn, anxiously checking whether his mother might be able to read any of them. He finished the proofs on 18 September.

In the meantime, on 9 September he had received a response to the ‘Saga’ from Hueffer, who told him that it was ‘a rotten work of genius, one fourth of which is the stuff of masterpiece’ and that it had ‘no construction or form’. Hueffer thought it ‘execrably bad art, being all variations on a theme’; more worryingly, he found it ‘erotic – not that I, personally, mind that, but an erotic work must be good art, which this is not.’ He suggested that publishing the novel might ‘damage’ Lawrence’s reputation, ‘perhaps permanently’ (1L 178, 339). This posed a genuine problem for Lawrence because while he was inclined to trust Hueffer’s judgement where his literary career was concerned, he was also aware that he was contracted to offer the novel to Heinemann.

(ii) ‘Paul Morel’

Fortunately, a potential solution emerged. In early October Lawrence sketched out a detailed chapter plan for a two-part novel in one of his College notebooks.7 He had begun work on ‘Paul Morel’, a novel drawing on events in Lawrence’s own early life, and on the lives of his friends and extended family; the plan suggests that it was to be more tightly structured and economical than the ‘Saga’. When he wrote to Sydney Pawling on 18 October he described the ‘Saga’ as ‘the rapid work of three months’; he told Pawling that if it were not to Heinemann’s taste, then he would be ‘content to let it lie for a few years’ and could offer him ‘Paul Morel’ instead. He reassured him that this was ‘plotted out very interestingly (to me)’: it would be a ‘restrained, somewhat impersonal novel,’ not ‘a florid prose poem’ (like the ‘Saga’) or ‘a decorated idyll running to seed in realism’ (like The White Peacock) (8L 4).

‘Paul Morel’ was the latest in a line of realist writings he had produced since autumn 1909 and, unlike the ‘Saga’, it was the kind of provincial working-class fiction of which Hueffer would approve. In the first months under Hueffer’s mentorship Lawrence had deliberately attempted to tone down the romantic and ornate features of his writing in favour of the quieter autobiographical realism of ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’, A Collier’s Friday Night and the two fictional sketches of December 1909 (‘A Lesson on a Tortoise’ and ‘Lessford’s Rabbits’). ‘A Blot’ (written in April 1910 and later revised as ‘The Fly in the Ointment’) would employ the same first-person narrator as the earlier short sketches: its graphic account of a penurious young man breaking into the back kitchen of the narrator’s lodging house (closely based on Colworth Road), and being bluntly upbraided for it, shows Lawrence depicting in extremely unsympathetic terms the social deprivation he witnessed around Croydon and in school. However, while such realism was well suited to drama and short sketches, it could easily lapse into melodrama or sentimentalism in longer third-person short stories. For example, in the surviving fragment of the earliest version of ‘Delilah and Mr Bircumshaw’, a tale written in January 1910 and focusing on the power games played between a young married couple, the brisk comedy of the dialogue between Mrs Bircumshaw and Mrs Cullen gives way in a rather studied fashion to a darker, naturalist emphasis on the brutish animality of the former’s ‘lusty’ husband and his loss of self-esteem under the ‘scorn’ of his wife (LAH 197). Around the same time, Lawrence had experimented with the realist style in a piece entitled ‘Matilda’: it was set in Croydon, but the plot was based on events in his mother’s youth, and particularly on an early and fondly remembered relationship she had with a sensitive, artistic man. This projected novel stalled 48 pages in, shortly after the beginning of the second chapter.8 Lawrence read it through in late July as he was working on his third revision of ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’ and found it ‘rather foolish’: he decided to ‘write her again when I’ve a bit of time’ (1L 172). Instead, in October he finished writing his second play, The Widowing of Mrs. Holroyd, which was closely linked in subject matter to ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’; this was completed by 9 November.9 He then turned his attention to ‘Paul Morel’: the challenge was to exploit the strengths of his realist sketches and dramas in a longer work of fiction.

Lawrence’s interactions with Heinemann in the next few months proved frustrating. Hueffer did not forward the manuscript of the ‘Saga’ to the publisher until mid-October; by 14 November Lawrence had still received no response to it, so he wrote to Pawling asking whether he had ‘temporarily forgotten the matter’ (1L 187). He would hear nothing back until late January. He was anxious to receive an advance copy of The White Peacock to show to his mother, who was getting ‘rapidly weaker’ (1L 186). She had been brought back to Eastwood at the end of September; Lawrence was now visiting her on alternate weekends. Other commitments kept him busy, too. At work he was helping the pupils to prepare for a performance of W. B. Yeats’ play ‘A Pot of Broth’ at the School Concert on 30 November; he painted stage scenery and helped to adapt the script.10 Reading this dialect comedy may have encouraged him to begin The Merry-go-Round, his own comical dialect play set around a bed-ridden mother; he worked away at this during late November and December. It is full of wildly energetic word-play and farce involving a vicar and a pet goose; it concludes with three marriage declarations in a scene which directly alludes to As You Like It (another play which Lawrence was about to teach at school).11 He told Violet Hunt: ‘When things get too intolerably tragic one flies to comedy, or at least romance’ (1L 200).

Lawrence was also asked by the Croydon branch of the English Association to give a paper on a living poet. He chose to briefly introduce the work of Rachel Annand Taylor, a Scottish poet and fellow-contributor to the English Review whose verses in the October 1909 number he had found ‘exceedingly good’ (1L 141); he had subsequently met her at one of the poetry evenings organised by Ernest and Grace Rhys. He now wrote to her, asking whether he could borrow some volumes of her poetry, and he went to visit her on 15 October, on one of the Saturdays he spent in Croydon. He felt that his paper on her in mid-November went down ‘very well’ (1L 189); an Inspector of Schools who was not kindly disposed towards Lawrence later recalled the ‘thrill’ that went through the audience when he announced her name in a dramatic fashion and ‘went on to chant her jewelled verbosities.’12 The provocative, ironic and restless quality of the script, and the animated nature of its delivery, were evidently intended to liven up the ‘vague, middle-class Croydonians’ (1L 179).13 Lawrence told Taylor: ‘It was most exciting. I worked my audience up to red heat – and I laughed’ (1L 191).14

There was, however, a manic quality in such exuberance: the paper was delivered around the time that Lawrence was told by the doctors that his mother had only a fortnight to live.15 On 23 November, the school allowed him to return to Eastwood to be with her. Ada was constantly by her bedside; a trained nurse, Florence (or ‘Flossie’) Cullen, the daughter of a family friend, helped to care for her;16 and Louie Burrows continued to visit. On 2 December Lawrence finally received his advance copy of The White Peacock. When he showed it to his mother she could do no more than glance at it. Later she asked what the inscription said and Ada read it to her: ‘To my Mother, with love, D. H. Lawrence’ (1L 194).

(iii) Engagement to Louie

On the following day, Saturday 3 December, Lawrence met Louie in Leicester. While taking her home on the train to Quorn, during the final leg of the journey from Rothley Station, he proposed to her and was accepted. He told Rachel Annand Taylor that it was ‘quite unpremeditated’ (1L 190), and he offered Arthur McLeod back in Croydon a detailed account of it, ending: ‘What made me do it, I cannot tell. Twas an inspiration. But I can’t tell mother’ (1L 193). This seems to have been another of those instances in which Lawrence laid claim to a form of spontaneity that was more imaginary than real. He told Louie that he had raised the possibility of marriage to her with his mother ‘a month or six weeks’ before: after initial resistance to the idea, she had agreed to it so long as he would ‘be happy with her’ (1L 197). The problem, as he saw it, would be financial: he informed Louie that he had just £4 4s 2½d to his name; she admitted that she did not have ‘twice as much’ (1L 194), but she had just secured a new post as headmistress at a school in Gaddesby, Leicestershire, at a salary of £90.17

Lawrence returned to nursing his mother. In the quiet spells he copied a painting – Frank Brangwyn’s ‘The Orange Market’ – for Ada. It is likely that his uncle, Fritz Krenkow, a keen Arabist, passed on to him a copy of Heinrich Schäfer’s Die Lieder eines ägyptischen Bauern, containing parallel texts of Egyptian ‘Fellaheen’ folk songs in Arabic and German; Lawrence turned his hand to translating some of these from German into English, sending them on to Louie as he did them. Witnessing his mother’s suffering caused him to reflect closely on the conflict that she had experienced in her marriage to his father, and on the bond that he as the youngest son had shared with her. He wrote to Rachel Annand Taylor: ‘We have been like one, so sensitive to each other that we never needed words. It has been rather terrible, and has made me, in some respects, abnormal’ (1L 190). In the same letter, he told her about his engagement to Louie, as if indicating that one bond replaces another, though he also stressed that Louie was not possessive like Jessie and could not have the soul of him, which had already been claimed by his mother.18 He wrote to Louie: ‘I must feel my mother’s hand slip out of mine before I can really take yours’ (1L 195).

(iv) Death and love

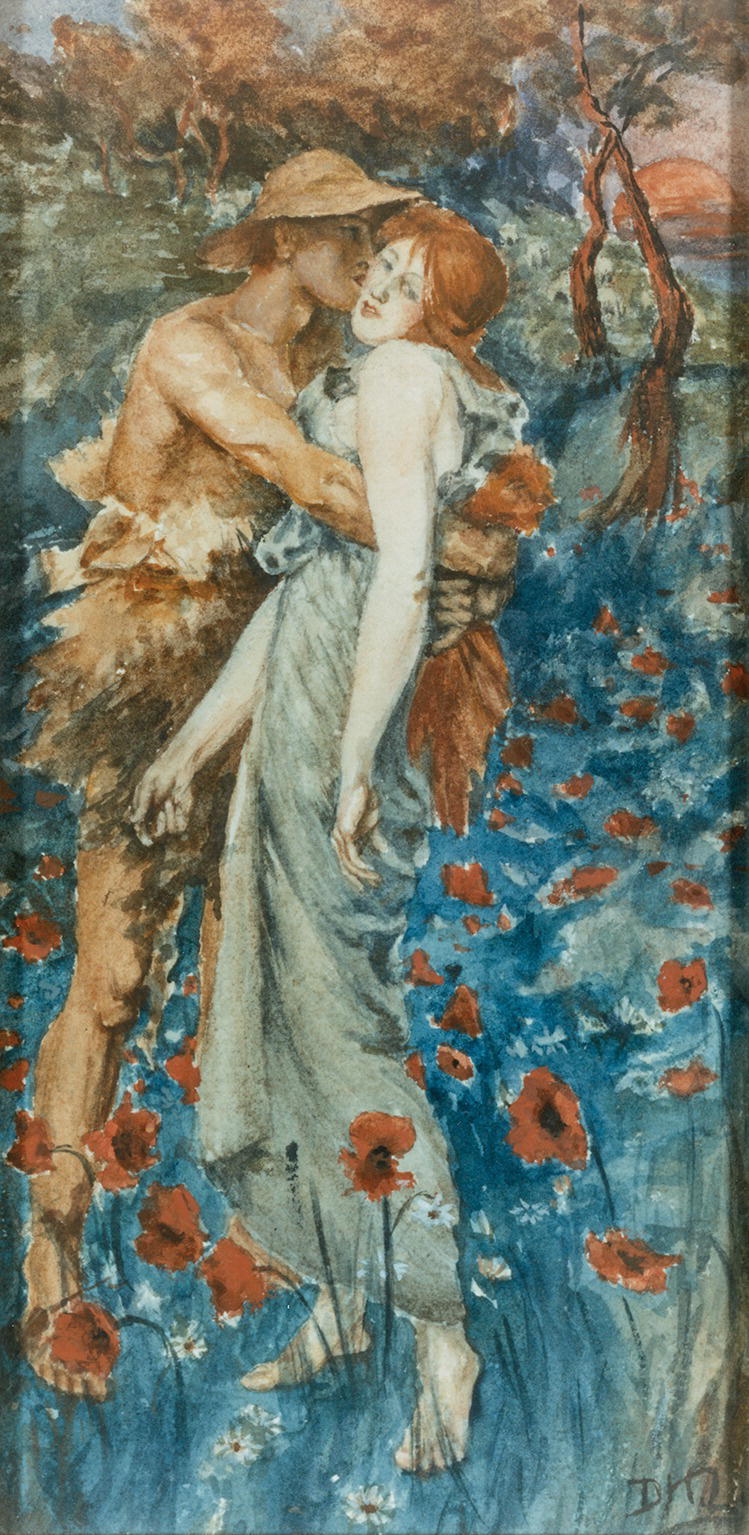

Lydia Lawrence died on Friday 9 December. On the night of her death Lawrence began the first of his four copies of Greiffenhagen’s ‘An Idyll’: his decision to paint this image of male passion and female submission at precisely this point arguably reveals the extent of his reflection on his parents’ unhappy marriage and how it might differ from his own engagement to the conventional and sexually reticent Louie.19 It was a way of thinking through the love he had felt for his mother, the ways in which it had shaped him, and how it might be transmuted into other kinds of attachment. During a miserable walk with Jessie the following Sunday, he told her that he had ‘always loved mother … loved her, like a lover. That’s why I could never love you.’20

Lydia was buried amid teeming rain the next day; Lawrence returned to Croydon immediately afterwards and taught out the remainder of the term. He made some half-hearted enquiries about moving to a country school as a headmaster in order that he could earn enough money to marry early (he requested an application form for a position in Truro, Cornwall, with a salary of £115).21 At some point in the final weeks of the year he received an urgent request from Heinemann for a last-minute change to the phrasing of a short passage in The White Peacock; he dealt with this straight away. In between work commitments he continued to translate the folk songs and to paint: he produced a very striking still-life watercolour of a ginger jar and three oranges (the arrangement had been set as an exam subject for his pupils).22 He did not go to Eastwood for Christmas this year, instead taking a week’s holiday (from 24 to 31 December) in Brighton with Ada and Frances Cooper before travelling to Quorn to see in the new year and spend the rest of the holiday with Louie.

Lawrence returned to Croydon on 8 January. He soon heard from Ada that she was having problems with their father. Arthur had stopped working as a butty between April and September, and was now employed as a dayman in other butties’ teams. The miners’ strike had ended on 25 November but he was still working reduced hours; he had made Ada angry by withholding money needed for housekeeping and using it to go out and get ‘drunk or tipsy.’ Lawrence sent letters to both Ada and his father trying to smooth over the situation, then wrote to the Reverend Robert Reid seeking help. He described his father as ‘disgusting, irritating, and selfish as a maggot,’ but also expressed some pity, since ‘he’s old, and stupid, and very helpless and futile’ (1L 220). Following his mother’s death Lawrence felt an aversion from Eastwood. On 9 February he told Ada: ‘I shan’t come home to Lynn Croft. I don’t much want to come to Eastwood at all’ (1L 229). A month later, on 9 March, the surviving family came together when Ada and her father went to live with Emily, her husband Sam King and their two-year-old daughter Margaret at Bromley House in Queen’s Square. Lawrence told Ada that there was nothing he really wanted from the old house ‘saving the woman, and, if you like, the black vases, which will always remind me of home: not, God knows, that one wants too much to be reminded thereof.’ He claimed to ‘hate Eastwood abominably … I should be glad if it were puffed off the face of the Earth’ (1L 233).

Figure 4 The copy of Maurice Greiffenhagen’s painting ‘An Idyll’ made by Lawrence for his sister Ada and begun on the day of his mother’s death, 9 December 1910. (Manuscripts and Special Collections, The University of Nottingham, La Pc 2/7.)

It was perhaps easier for Lawrence, away in Croydon, to draw a line under all that his home had meant to him than it was for Ada. The strain of nursing her dying mother and then having to keep house for her father resulted in a painful loss of faith; by late March she was ‘dipped into disbelief’ (1L 248). Lawrence, sensitized to her situation by his own loss of faith at College, responded by writing her a remarkably supportive and understanding letter: he offered to send her some books of philosophy if they would help, but he also stressed the need for her to gradually discover her own beliefs and religious awareness. He told her that it is ‘a fine thing to establish one’s own religion in one’s heart, not to be dependent on tradition and second hand ideals’ (1L 256).

Lawrence and Ada had always shared a special connection: the experience of caring for their mother brought them even closer together. Lawrence reassured Ada that she was his ‘one, real relative in the world’ (1L 231) and that she had no reason to be jealous of Louie. In fact, Lawrence wanted to protect Louie from the suffering that he and his younger sister had witnessed in their mother’s marriage, since his fiancée had ‘seen nothing whatever of the horror of life’ (1L 230). Louie had a stable family background and a firm Christian belief; she had taken the same route to a teaching career as Lawrence (attending the Ilkeston Pupil-Teacher Centre and Nottingham University College) without suffering comparable doubts and disappointments along the way. Although she was a committed suffragist and Lawrence had nurtured her interest in writing short stories, she did not have the same intensity of engagement with reading as Jessie, nor the same tragic outlook. It is easy to see the attraction of a woman like Louie for Lawrence after his experiences with his mother, Jessie and Helen Corke. He told Rachel Annand Taylor: ‘When I think of her I feel happy with a sort of warm radiation – she is big and dark and handsome’; elsewhere he described her as ‘a glorious girl: about as tall as I, straight and strong as a caryatid … and swarthy and ruddy as a pomegranate, and bright and vital as a pitcher of wine’ (1L 190, 193). Any doubts about their compatibility were initially quelled by Lawrence’s determination that her warmth and liveliness should bring about a fresh departure in his life.

Their engagement began optimistically. They agreed that in order to marry Lawrence would need to have ‘£100 in cash and £120 a year income.’ Although his current wage was just £95 per annum, and with contributions to his father’s upkeep he would not be able to save ‘£5 a year without descending to petty carefulness’ (1L 223), he was hopeful that future literary earnings might significantly supplement his income. Much would depend on the reception of his first novel: if it was well reviewed, then Lawrence felt it would break him an entrance into ‘the jungle of literature’ and help him to establish ‘a small but individual name’ (1L 222). Heinemann published The White Peacock on 20 January (for copyright reasons it was published in New York, by Duffield, the day before). After an anxious fortnight waiting for notices to appear, it began to receive a pleasing amount of attention. The review in the Times Literary Supplement was rather critical, but those in the Observer, the Standard and the Daily News were more positive. Violet Hunt wrote a glowing review in the Daily Chronicle, as did Henry Savage in Academy, and Willie Hopkin was typically supportive in the piece he wrote for the Eastwood and Kimberley Advertiser.23

Lawrence now heard back from Frederick Atkinson about ‘The Saga of Siegmund’: Atkinson admitted that he did not particularly like the parts he had read, but he agreed to publish it all the same.24 Lawrence – acting on Hueffer’s advice – responded by restating his determination not to release it on the grounds that it had ‘no idea of progressive action,’ was too ‘chargé’ in its ‘purple patches,’ and was ‘finally, pornographic’ (1L 229). He asked for the manuscript to be returned to him. This meant, however, that he would need to make rapid progress with ‘Paul Morel’ if his second novel was to benefit from the publicity generated by The White Peacock. Unfortunately that novel had stalled back in November ‘at the hundredth page’ (1L 230): he had not had the heart to go back to it since his mother’s death. Extra claims were now being made on Lawrence’s money (in addition to the support he was offering to his family back in Eastwood, at the end of January he was asked to contribute to a friend’s medical costs).25 To make matters worse a threat of legal action was brought by the family of Alice Hall, a contact in Eastwood, over her portrayal as Alice Gall in The White Peacock (Willie Hopkin had to diplomatically step in and sort out the situation).26

Lawrence’s mood in the midst of all this was thoroughly fatalistic. He was reading Gilbert Murray’s translations of Greek tragedies and urging Louie to adopt his own attitude: ‘I wish all this toil of writing were put away, and we were perfectly untroubled and unanxious, in a quiet country school. – But who can alter fate, and useless it is to rail against it’ (1L 235). The mood during Louie’s visit to Croydon on the weekend of 11–12 March must have been sombre, since afterwards Lawrence admitted that they could not marry ‘yet awhile for a long time’ (1L 237). Cracks were already starting to appear in their relationship: while Louie was perturbed by his failure to save money, jealous of Jessie’s continuing presence in his life, and upset by her family’s disapproval of her engagement, Lawrence was finding it increasingly difficult to accept Louie’s refusal to respond to his physical advances. He told her that she made him ‘ashamed of passion’ (1L 242); he confided to Ada that he was ‘a bit off in health,’ but ‘Lou doesn’t understand a bit – and I never say anything. I’m afraid she’s one I shan’t tell things to – it only seems to bother her’ (1L 243).

There was, however, another pressing reason at this time for Lawrence to adopt a principle of secrecy where Louie was concerned: he was still sexually attracted to Helen Corke. A letter of 14 March shows that he had asked Helen to become his mistress, and that she had once again put him off by offering him intimacy without sex.27 He responded: ‘We are always so intimate, vitally – that the other seems to me merely natural, like a phrase in the conversation. If it is not natural and good, God is an idiot’ (1L 239). His frustration was exposing self-divisions in his nature. His newly discovered love of Italian opera, for instance, convinced him that he was ‘just as emotional and impulsive’ as the Italians, but the English climate and his upbringing had made him ‘cold-headed as mathematics’ (1L 247). He rebelled against the ‘black suit of convention,’ feeling like ‘a very wicked and riotous person got up to look and behave like a curate’ (1L 259). The immediate reference here is to the black suit which he continued to wear as a public sign of mourning for his mother: he clearly felt the disparity between wearing these sombre clothes for the sake of social convention and continuing (in private) to experience the attraction to Helen. Louie’s ‘churchy’ (1L 343) attitudes meant that he was forced to speak in code in order to express his sexual frustration. He would use French in his letters when he wished to be more outspoken, signing off with ‘je te cherche, bouche et gorge, pour t’embrasser’ (1L 259) (‘I long for you, mouth and throat, to kiss you’) or ‘Hélas, que vous êtes loin d’ici, que votre corps loin du mien’ (1L 263) (‘Alas, how far you are from me, how far your body from mine’). Although in Lawrence’s early letters to Louie he willingly adopted the role of the blundering lover chastened by his fiancée’s meek ways, its comic potential soon wore thin as their underlying differences started to be felt.

During their weekend together in Croydon Lawrence and Louie would have spoken about their difficult financial position. It is probably no coincidence that the day after Louie’s return to Leicester he wrote to her announcing: ‘I have begun Paul Morel again.’ The tone of his letter, however, makes it clear that in his current mood he shrank from the prospect of writing a novel dealing with his own early life and family. A few days before his mother’s death he had stated that ‘after this … I am going to write romance – when I have finished Paul Morel, which belongs to this’ (1L 195). Now he told Louie: ‘I am afraid it will be a terrible novel’ (1L 237).

As he began to work away at ‘Paul Morel’, in mid-March Austin Harrison wrote to request a review copy of The White Peacock and asked whether Lawrence had any stories he could send to him at the English Review. He worked up ‘A Fragment of Stained Glass’ and (once again) ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’, sending the heavily revised proofs of the latter story – now with three layers of revision – to Louie so that she could produce a legible copy. Re-writing the ending took him ‘such a long long time’: ‘You have no idea how much delving it requires to get that deep into cause and effect’ (1L 250). ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’ would finally be published in June 1911; ‘A Fragment of Stained Glass’ appeared in September. In April he polished up two more stories: ‘The White Stocking’ and ‘The Shadow in the Rose Garden’ (a story which drew on ‘The Vicar’s Garden’, written way back in autumn 1907).

(v) ‘Intimacy’

In March or April 1911 Lawrence may also have written an early version of a new short story entitled ‘Intimacy’ (later revised as ‘The Witch à la Mode’).28 Its setting derives from the musical evenings he had started to attend in Purley, hosted by Laura Macartney, the sister of Herbert;29 the plot explores Lawrence’s attraction to Helen on these occasions, and his near infidelity to Louie. It follows its central protagonist Bernard Coutts, a civilised man of weak character, as he drifts back into his former intimacy with Margaret Varley, only to run away from her at the moment of physical contact. As the story opens, Coutts is returning from a stay in France to his fiancée at their rectory home in Ingleton, a village in the Yorkshire Dales (the Louie-figure in this story is located in the north and strongly associated with religious propriety). Coutts breaks his train journey from Newhaven to Ingleton in Croydon, the town which he had left five months earlier; he convinces himself that he is stopping there on purely practical grounds, but his excited reflection on the spark which jumps from the overhead wires of the tramcar – ‘Where does it come from?’ (VicG 125) – suggests that he is already anticipating the possibility of romantic transgression with his former love.

The most remarkable aspect of the story is the subtle manner in which it critiques Coutts’ attitude to his situation. His impulsiveness is overlaid with a troublingly romantic self-consciousness and capacity for self-delusion which the story connects to his cultured sensibility. He is attuned to the symbolic potential of the electric spark and the ‘blade of the moon,’ while the tawdriness of his real motives goes unacknowledged. Coutts enters the home of the young widow, Laura Braithwaite, in Purley and is immediately ensconced in the drawing-room environment which nurtured his artistic temperament at the expense of trapping him in a state of emotional deadlock. In a comical and poignant moment, Laura and her father, Mr Marston, discuss the mysteries of ‘Free Will’, and we are told that ‘Coutts showed his teeth in a smile’ (VicG 127). The drawing room vibrates to the music of Chopin, Brahms, Grieg and Saint-Saëns, while the evening moves towards its thrilling climax. Back at Margaret’s house in Croydon they enter into a familiar, intimate and fraught dialogue which gives way to a physical embrace and kissing, until Coutts knocks over the stand holding a tall ivory paraffin lamp, which smashes on the floor, setting fire to her silk dress. He smothers the flames on her, then leaves the house, ‘running blindly,’ his hands burnt and his face singed (VicG 138). He had earlier reflected that Margaret was ‘a tragic woman’ (VicG 132) who had gone through one love tragedy and might suffer more; he has allowed himself to be drawn into the destructive orbit of her life, and believes himself literally and metaphorically burned by the passion they invoke in one another.

(vi) Kinds of betrayal

Lawrence was growing accustomed to exploring his own motives in an analytical mode in his fiction. The process was both fascinating and painful. ‘Paul Morel’ continued to progress very slowly: on 12 April Lawrence referred to it as a ‘great, terrible but unwritten novel’ and was ‘afraid it will die a mere conception’ (1L 258). After spending a little over a week in Eastwood and Quorn in the Easter holidays, he braced himself to return to work on it, but found it hard to settle to the task: on 28 April he complained to Louie that ‘I simply cannot work. I have done only about five pages of MSS, ‘Paul Morel’; and that only from sheer pressure of duty’ (1L 262). Three days later he had made the resolution to write at least 10 pages per day.30 This taxing schedule created a high degree of anxiety in him, which on occasion found expression in irritable outbursts; for example, on 9 May he asked Louie ‘Am I a newspaper printing machine to turn out a hundred sheets in half an hour?’ (1L 266).

Around this time Lawrence received a short story from Jessie based on the devastating conversation they had had back on Easter Monday 1906: on that occasion, in carrying out his mother’s (and Emily’s) injunction to clarify the terms of their relationship, Lawrence had told Jessie that he could not love her as a husband should love his wife. Jessie’s purpose in sending the story to Lawrence was to stress the damaging effect that his mother’s love for him had had on the subsequent course of their romantic involvement; in Jessie’s own much later words, she ‘wanted to make the effect of his mother’s attitude clear to him’ on the understanding that the pain this would cause ‘might lead to health.’31 Lawrence’s initial response on reading the story was far more pragmatic. He told her: ‘I don’t think you’ll get anyone to publish it with alacrity; it’s too subtle’ (1L 268). This struck Jessie as being a pose of detachment, but in fact it demonstrates Lawrence’s instinctive tendency to treat the claim to truth in her story as subordinate to issues of literary form. During the later stages of his work on ‘Paul Morel’ he would rely a good deal on Jessie’s clear recollection of their youth, but he also reserved the right to shape reality to his own artistic aims: his need to discover patterns and meanings in past experiences required a degree of control and single-mindedness which could seem like a cruel betrayal to the people who were closest to him.

At the end of May he sent most of the ‘Paul Morel’ manuscript to Louie for her comments, only keeping back some of the latest writing in order to continue working on it. He asked her to ‘collect and correct’ the ‘heterogeneous’ manuscript (1L 263), as she had done with the almost illegible proofs of ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’. He refused to let her see his latest poetry notebook, however, since it contained poems relating to both Jessie and Helen;32 these, like ‘Intimacy’, referred to aspects of his life which he kept hidden from her. The prudence of his decision to withhold them was demonstrated in late June, when Louie appears to have reacted negatively to the short story ‘The Old Adam’,33 a tale of passion and simmering resentment in which Lawrence – extrapolating from his own position at Colworth Road and his closeness to Marie Jones – explores the situation of a young lodger who wins the affections of his landlady and comes to blows with her jealous husband.34

Lawrence’s contractual commitment to Heinemann weighed heavily on him as he struggled to work on ‘Paul Morel’, but during summer the publicity generated by The White Peacock relieved the tension by opening up new publishing contacts and possibilities. On his return to Croydon from his short Whitsuntide holiday in the Midlands he found a letter waiting for him from Martin Secker, who had read and admired The White Peacock and ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’ and wanted to know whether Lawrence would be interested in publishing a collection of short stories with his new company (which he had set up the year before).35 Lawrence wrote straight back on 12 June saying that he was ‘very much flattered’ (1L 275) and hoped that some of the stories he had to hand might be sufficient for a volume. Secker gave him the option of working towards publication the following spring.36 Stories were proving to be quite an attractive option for him, and a lucrative one, too (in July he would receive £10 from the English Review as payment for ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’: twice the sum he had expected).

Lawrence enjoyed the luxury of a further one-week holiday in the Midlands from 16 to 25 June to celebrate the coronation of King George V, but this interrupted the rhythm of his writing. ‘Paul Morel’ stalled again in mid-July at around page 353; he abandoned the draft just as he was finishing a long story entitled ‘Two Marriages’ (later revised as ‘Daughters of the Vicar’). On 17 July he wrote to Louie in desperation, telling her that he had ‘not done any Paul lately. I’ve only done a short story’: ‘I am a failure at everything tonight – writing, verse, painting, reading, everything … This evening, and last evening it’s been ghastly. – But what’s the use of talking’ (1L 288-9). Tensions had come to a head with his inability to finish the novel, but other factors lay behind the outburst. In May Louie had applied for, and secured, a new post as headmistress at the Quorn Church of England Junior School;37 the job officially began on 1 September, but she was allowed to leave Gaddesby early, so by 17 July she was contemplating returning to live with her parents. Lawrence felt that this would rob her of her independence and place still further limitations on their freedom to be together. Another factor in Lawrence’s upset was Helen Corke. A letter he wrote to Helen on 12 July alludes to the ongoing ‘sex strain’ between them; he had been with Helen the previous weekend (8–9 July) and after leaving her on the Sunday evening had disposed of two condoms given to him by Jones some months before. He now declared that he would ‘never ask for sex relationship again, never, unless I can give the dirty coin of marriage.’ He told Helen: ‘I love Louie in a certain way that doesn’t encroach on my liberty, and I can marry her, and still be alone.’ This all sounds very much like making a virtue of necessity: his resentment of Helen’s resistance to his advances is evident in his petulant remark that in future he will only have sex with a prostitute ‘whom I can love because I’m sorry for her’ (1L 285–6).

Problems arose after Louie moved back into her parents’ home, ‘Coteshael’. Their opposition to the engagement put Louie in an awkward position; for his part, Lawrence was very conscious of the parents’ conservatism and was now careful in his letters to use French when expressing any opinion either about them or Louie’s situation. The end of term came as a great relief. He went on holiday with Ada and Louie to Prestatyn from 29 July to 12 August (they were joined at some point by George Neville). On his return Lawrence visited various friends back in the Midlands: he stayed with his former headmaster, George Holderness, in Eakring; he went to see Alice and Harry Dax in Shirebrook, ten miles north of Eastwood (they had moved there in summer 1910); and he briefly stayed with his former College friend, Tom Smith, in Lincoln, cutting the visit short to return to Quorn and spend the final days of the holiday with Louie.

(vii) Edward Garnett

Then, on 25 August, out of the blue, Lawrence received a letter from Edward Garnett, a very experienced and respected literary adviser to the publishing firm of Gerald Duckworth, and the man who had helped to launch the career of Joseph Conrad. Garnett’s letter had been sent to Heinemann some weeks before and forwarded via Croydon. He had written to Lawrence on behalf of the New York publishing house Century Co., requesting some short stories for their magazine, the Century. Lawrence responded enthusiastically, promising to send Garnett several of the stories he had to hand once he was back in Croydon. This opportunity was sufficient to offset the disappointment of having The Widowing of Mrs. Holroyd rejected by the playwright, producer and critic Harley Granville-Barker a few days later (Hueffer having forwarded it on Lawrence’s behalf).38 Lawrence submitted a few stories to Garnett, including ‘Intimacy’, but Garnett returned them on the grounds that they were insufficiently commercial and unsuitable for an American readership; he felt that ‘Intimacy’ took too long to build tension. On 20 September Lawrence went to dinner and the theatre with Austin Harrison, who asked him to ‘do a bit of reviewing for the English’ (1L 305): he would write reviews of three volumes of German verse by the end of the year.39 After moving with the Joneses two doors down, from 12 to 16 Colworth Road, on 22 September, he sent ‘Two Marriages’ to Garnett, hoping that this longer story might be serialised in the Century. Garnett responded very positively to it; he asked Lawrence to split it into three parts, and arranged to meet him on 4 October. However, as they ate lunch together Frederick Atkinson came into the same restaurant: he would have been surprised to see Lawrence meeting a reader for a rival publisher. Garnett was ‘sarky’ to Atkinson. Lawrence noted Garnett’s dislike of ‘Heinemann’s people’; it was an attitude that Lawrence himself was quick to adopt. Heinemann had been slow to send proofs of The White Peacock to him the previous summer, and they had been tardy and unenthusiastic in their response to the manuscript of ‘The Saga of Siegmund’. Lawrence told Louie: ‘I hate Atkinson – I don’t go to Heinemanns because I don’t like the sneering, affected little fellow’ (1L 310). In a later letter to Garnett he sarcastically referred to Heinemann as ‘the Great Cham of publishers’ (1L 326).

Lawrence found Garnett ‘quite sweet’; he was invited to spend a weekend at the Cearne, Garnett’s house in Edenbridge, Kent. Garnett’s enthusiastic advocacy of the full range of Lawrence’s writing was clearly very welcome at a time when he had chosen to hold back his second novel from publication and was struggling to complete his third. Lawrence immediately looked to Garnett for advice and support. In anticipation of his visit he sent Garnett the manuscript of The Widowing of Mrs. Holroyd, and promised to send him the other two plays he had written once Hueffer returned them. Garnett mentioned the possibility of publishing a volume of his verse with Duckworth in the spring.

Before his first visit to Garnett’s home, Lawrence entertained his brother George in Croydon over the weekend of 7–8 October. On the evening of Saturday 7 October the two went to the Savoy Theatre, where they met Helen and Jessie (apparently without design, though the coincidence of their attendance at the same performance suggests that it was planned).40 Jessie was staying with Helen in Croydon for the weekend: Lawrence spoke to them during the interval. He had not had contact with Jessie for around six months prior to this meeting; it now prompted him to send the incomplete manuscript of ‘Paul Morel’ to her, to seek her response to it.

The following weekend at the Cearne, 13–15 October, confirmed Lawrence’s initial feelings about Garnett: he was impressed by the house, which was 13 years old but ‘built in the 15th Century style’ (1L 316): it had a ‘brick floored hall, bare wood staircase, deep ingle nook with a great log fire, and two tiny windows one on either side of the chimney: and beautiful old furniture – all in perfect taste.’ He reported back to Louie on the unconventional living arrangements Garnett had established with his wife, Constance: ‘He is about 42. He and his wife consent to live together or apart as it pleases them. At present Mrs Garnett with their son is living in their Hampstead flat. She comes down to the Cearne for week ends sometimes’ (1L 314–15). Louie was unlikely to respond enthusiastically to such marital arrangements; Lawrence’s instant ease in this environment illustrates the extent of his detachment from the restrictive values of her parents’ home.

Garnett proved to be ‘beautifully free of the world’s conventions’ (1L 362). He and Lawrence ‘discussed books most furiously’ during that first weekend together. Garnett flattered Lawrence, praising him for the ‘sensuous feeling’ in his writing; he expressed an interest in frank writings about sex and sexuality, telling Lawrence that he would ‘welcome a description of the whole act’ (6L 520). Garnett had clearly decided to mentor Lawrence and take some responsibility for nurturing his career: he offered to introduce Lawrence to a new set of literary contacts and told him that his ‘business’ was ‘to get known’ (1L 315). Shortly after his return, though, Lawrence was invited to lunch with Heinemann, who now acted to defend his investment: like Garnett he offered to publish a volume of verse in the spring, and he made Lawrence promise to give him ‘Paul Morel’ in March and hold back on delivering the stories to Secker until the autumn. Lawrence was inclined to think it ‘a fairly good arrangement’: he asked Garnett to return the batch of poems he had forwarded to him, with the observation that ‘I know you are not keen on verse’ (1L 317).

Garnett’s personal interest in Lawrence’s writing was, however, far more important in many respects than the contracts and readers’ reports that Heinemann supplied. Garnett sent copies of his own plays to Lawrence: Lawrence was particularly struck by The Breaking Point (1907), in which an inexperienced girl who falls pregnant by a married man commits suicide because she is unable to reconcile the conflicting claims made on her by her lover and her stern academic father.41 Lawrence admired the play’s ‘clean bareness … It is a fine, clean moulded tragedy, The Breaking Point’; he compared it favourably to the plays he had recently written, with their ‘ravels of detail’ (1L 317). Garnett asked to see Lawrence’s writing with a view to discussing its suitability for particular readerships. He began by placing two of Lawrence’s poems, ‘Lightning’ and ‘Violets’ (the revised version of ‘Violets for the Dead’), with the Nation, ‘a sixpenny weekly, of very good standing’ (1L 324); they appeared on 4 November 1911. One of the first contacts he sought to introduce Lawrence to was Rolfe Arnold Scott-James, literary editor of the Daily News, the newspaper that had described the characters in The White Peacock as insufferably cultured and taken issue with its ‘cloying descriptiveness’ and cleverness.42 The idea was to expose Lawrence’s work to new readerships and encourage him to consider such criticisms in a new light; Garnett was also, like Hueffer, intent on drawing out from Lawrence some ‘more objective, more ordinary’ (1L 304) writing about Eastwood. Under his mentorship Lawrence was immediately encouraged to write three more dialect poems: ‘The Collier’s Wife’, ‘Whether or Not’ and ‘The Drained Cup’.

The weekend of 27–29 October was spent in Quorn and Eastwood, meeting Louie and Ada, and spending a little time with his family. By 3 November, back in Croydon, he had received Jessie’s response to the manuscript of ‘Paul Morel’; on that day he announced that he was ‘going to begin Paul Morel again, for the third and last time … It is a book the thought of which weighs heavily on me.’ The comment would seem to reflect Jessie’s recommendation that he should draw more directly on his close family history in re-writing the novel. Jessie later claimed that she found the writing in this second draft of the novel ‘extremely tired’ and ‘story-bookish’.43 The fact that Lawrence had written it without her help may well account for her negative memory of it, but her feeling that it would benefit from a closer attention to the reality of everyday family life (and particularly from the inclusion of the details of Ernest’s death in October 1901) was astute and helpful. In the July 1911 version of the novel, Walter Morel kills his youngest son, Arthur, by throwing a steel (or knife-sharpener) at him during a heated domestic dispute; Lawrence was drawing on the sensational case of his paternal uncle Walter Lawrence, who had killed his 14-year-old son during an argument at their home in Ilkeston on 18 March 1900.44 When revising the novel, Lawrence would omit this dramatic incident and concentrate instead on the experiences of his nuclear family. He asked Jessie to write down her recollections of their early days together, since her memory was better than his own.45 Lawrence started the novel knowing that if he was to ‘keep it true to life,’46 as Jessie suggested, he would need – at least – to confront the death of his brother; he told Louie that he dreaded setting pen to paper and asked her to ‘Say a Misericordia’ (1L 321).

In early November, shortly after he returned to writing ‘Paul Morel’, Lawrence finished the first full draft of another long story: ‘Love Among the Haystacks’. It drew closely on his memories of working with Alan Chambers in fields near Haggs Farm in the summer of 1908 (the Chambers family had given up the Haggs in March 1910 and moved to a farm in Arno Vale). He sent it to Garnett on 11 November, asking him whether he should approach Austin Harrison with a view to serialising it in the English Review; Garnett evidently thought this a good idea, since he appears to have forwarded it to Harrison himself.47 This was the first Eastwood story that Lawrence had written under Garnett’s influence; the fact that he was asking Garnett about the possibility of serialisation shows how discussions with his mentor had caused him to think more seriously about literary commerce and about producing works tailored to individual journals and newspapers.

Garnett had spoken to Lawrence about giving up teaching and earning his living as a professional writer. As early as 15 September Lawrence had told Louie that he was ‘rather tired of school’ and broached the delicate subject of a change of employment: ‘Should you be cross if I were to – and I don’t say I shall – try to get hold of enough literary work, journalism or what not, to keep me going without school. Of course, it’s a bit risky, but for myself I don’t mind risk – like it’ (1L 303). He had been complaining about teaching ever since the start of the new school year at the end of August: he found the first few days back ‘pretty rotten’ and told Louie that he hated being in school ‘because of the confinement’ (1L 298–9). His dissatisfaction with teaching and desire to take his chances with writing clearly became more pressing as the weeks went by: on 11 October he told May Holbrook (Jessie’s sister) that Jones had just been ‘jawing’ him about ‘how to make my fortune in literature’ (1L 312). To Garnett he complained that lunchtime appointments in the week could barely be managed in his Davidson Road lunch break, and he painted a vivid picture of his current life: ‘I’m supposed to be marking Composition – such a stack of blue exercise books at my elbow. How’s that for MS? – it is awful: it’ll be the death of me one of these days’ (1L 318–19). By early November he was ‘really very tired of school’ and told Louie ‘I am afraid I shall have to leave – and I am afraid you will be cross with me’ (1L 326). He had begun to think seriously about how he might make the transition to living as a writer. Thinking about the payment of £50 owing on The White Peacock and the money that might accrue from his second novel and a volume of poetry, he wondered whether he could ask Heinemann to pay him a fixed yearly income of ‘£100 a year for one, or two years’ (1L 323).

(viii) Collapse and convalescence

Lawrence’s attempt to combine his full-time job with a burgeoning literary career was beginning to have consequences for his health. Since the beginning of the term he had been extraordinarily busy balancing commitments to work, to Louie, to his family, and to his writing. Inspectors had visited Davidson Road School on 13–14 September; there was the house move on 22 September; and since early October he had spent weekends with his brother George, Garnett, and Louie and Ada, in addition to fitting in various meetings with Harrison and Heinemann; he had also been seeing a lot of Helen Corke, and possibly Alice Dax, too. His letters contain uncharacteristic complaints about tiredness. On Wednesday 11 October, in the middle of a school week, he told May Holbrook that he had ‘worked all night at verse – you don’t know what that means’ (1L 312). Things came to a head in the week beginning Monday 13 November. That evening he went to see Wagner’s Siegfried in Covent Garden after school; on Thursday evening he was asked by George to take a friend of his to the theatre; on Friday evening he was invited out to a party organised by Mrs Smith, the wife of his headmaster; and on Saturday he travelled to Kent for another weekend with Garnett at the Cearne. In the midst of all this he was attempting to make plans for Christmas with Louie, and continuing to work – as best he could – on ‘Paul Morel’.

On Sunday evening, 19 November, he returned to Colworth Road feeling very ill; Jones later said that he looked ‘as if he was suffering from a frightful hangover.’48 It had rained the day before; he got wet en route to the Cearne and did not change his wet clothes. As a result he caught a chill which kept him off work. Over the next week it developed into double pneumonia. On 21 November he managed to dictate a note to Marie Jones and sent the typed and revised manuscript of ‘Two Marriages’ to Garnett for him to forward to the Century. Four days later Ada travelled down from Eastwood to look after him with the help of a nurse; the doctor gave him injections of morphia to help him sleep. Ada wrote to Louie to keep her informed; she asked Louie to avoid coming to Croydon, ostensibly on doctor’s orders, to keep Lawrence from getting unduly exercised about things (though it is likely that he would, in any case, have preferred to be nursed by his sister alone).

The crisis came shortly after 28 November. He survived it, but the process of recovery was very slow and frustrating for a man who was ‘by nature … ceaselessly active’ (1L 337). Only on 2 December was he able to scribble a short note to Louie, thanking her for sending flowers. Two days later he sent a letter to Garnett, enclosing the manuscript of ‘The Saga of Siegmund’, which had just been returned by Heinemann; he asked for Garnett’s opinion of it, noting that Hueffer had been ‘prejudiced against the inconsequential style’ (1L 330). By 6 December he was allowed to read again; on that day Garnett paid him a brief visit in the early evening. However, it would be a few more days before he could sit up in bed, propped up on pillows. Ada wrote to Louie again, informing her that the doctor was ‘emphatic’ that a visit from his fiancée might upset him (1L 331); to placate Louie, Lawrence wrote to suggest that she might visit at Christmas, and that they could perhaps go together to Bournemouth for a week in the new year, as part of his convalescence.

During his confinement Lawrence managed to write reviews of two books of German poetry for the English Review: The Oxford Book of German Verse and The Minnesingers.49 He reassured Louie that they were ‘only trifles’ (1L 336): he wrote and sent these off between 6 and 13 December. He received eggs from May Holbrook, two chickens from William Edwin (or ‘Eddie’) Clarke (Ada’s fiancé), and a letter from Agnes Holt, inviting him to visit her and her new husband in their home at Ramsey on the Isle of Man. A letter he wrote to Grace Crawford on 13 December suggests that he had also been in contact with Heinemann to extend the deadline for the submission of ‘Paul Morel’ from March to June.50 Sitting up to take tea was ‘a weird, not delightful experience’ (1L 337), and walking was more difficult still. On 18 December he reported that his legs ‘won’t hold me up’ (1L 340); two days later, though, he ‘strolled into the bathroom, prancing like the horses of the Walküre, on nimble air’ (1L 341). That week he began to sketch out another copy of Greiffenhagen’s ‘An Idyll’ (this time for Arthur McLeod) and wrote a story entitled ‘The Harassed Angel’ (later revised and retitled ‘The Soiled Rose’ and then ‘The Shades of Spring’), which he sent to Garnett on 30 December.

As he started to receive more visits from friends – from Eddie Clarke, Garnett (again), Lil Reynolds, and Helen and Jessie – it was becoming clear to him how much had changed in his life since the end of November. Although a sputum test had proved negative for tuberculosis, he informed Garnett that ‘The doctor says I mustn’t go to school again or I shall be consumptive’ (1L 337). In some ways this bout of pneumonia, like the one 10 years before, in 1901, had changed the course of his life for the better. Back then illness had rescued him from life as a clerk and bonded him more closely than before to his mother. Now it promised to remove him from onerous teaching commitments and gave him the perfect opportunity to try forging an alternative career as a writer. He was lucky to have Garnett there to advise him on the transition and to support him in other ways. His mentor lent him seven guineas to cover the cost of medical fees and his convalescence in Bournemouth, and (to Lawrence’s delight) he expressed enthusiasm for the problematic ‘Saga’ and offered to try publishing it with Duckworth (they soon settled on The Trespasser as a suitable new title for it).51 The mending of his health heralded a transformation in his circumstances.

(ix) Breaking off

These developments were always likely to alienate him still further from Louie. Without the security of a stable teaching job and the capacity to save, it would be impossible to maintain even the pretence of preparing for a future married life together. Lawrence told her on 9 December: ‘It is queer, how I have turned, since I have been ill.’ He now wished to leave Colworth Road as soon as possible: ‘I want to leave Mrs Jones, and Mr Jones, and the children’. His letters show how he began to be impatient, too, with Louie’s expressions of concern for him. When she finally came to visit him at Christmas he told Garnett that he was ‘not particularly happy, being only half here, yet awhile. She never understands that’ (1L 343).

Lawrence and Louie spent a couple of days with Lil Reynolds and her mother in Redhill, then Lawrence travelled alone to Bournemouth on 6 January. He would stay for three and a half weeks at a boarding house on St Peter’s Road named Compton House; it could accept around 80 guests, but had a regular occupancy during the week of 45 to 50. Lawrence’s adjustment to the new environment followed a familiar pattern. He initially felt quite lonely and ‘forlorn’ (1L 347), writing to various friends and contacts, and asking Garnett to send him some books,52 but he soon bonded with the people around him, so that by 21 January he could reflect how ‘Here I get mixed up in people’s lives so – it’s very interesting, sometimes a bit painful, often jolly. But I run to such close intimacy with folk, it is complicating’ (1L 354). His letters contain vivid sketches of the various people he met and dramatic accounts of the outings they took and the scrapes they got into.53 He kept in contact with at least two of his fellow guests after he left (the sisters Margaret and Irene Brinton).

Lawrence appreciated the warmer weather in Bournemouth, and he found the structure of the day quite amenable. He would wake at 8.30; take a substantial breakfast of ‘bacon and kidney and ham and eggs’ (1L 347) at 9.00; talk in the smoking room until 10.30; then work in his room until 1.30pm, when he would go for lunch, followed by a walk or card games in the recreation room. Although he suffered a ‘vicious cold’ (1L 352) in the first weeks of his stay, he soon began to put on weight. The three hours per day of work in his room allowed him to accomplish a great deal without being too taxed. Some negotiations for publication continued as he recuperated. Back on 30 December Lawrence had heard from Garnett that the Century had rejected ‘Two Marriages’; he sent him ‘The Harassed Angel’, which Garnett managed to place by 8 March with another American magazine, Forum (it would be published a year later, in March 1913, as ‘The Soiled Rose’). On 9 January Austin Harrison returned ‘The White Stocking’ but agreed to publish another story, ‘Second-Best’, straight away in the English Review (it appeared in the February number). Lawrence took the opportunity to revise The Trespasser: he toned down some of the purple patches and worked in particular on the old Chapter XII (entitled ‘The Stranger’), taking Garnett’s advice to make it ‘more ordinary & natural’ (T 323), less ‘literary’ (1L 353). Returning to the manuscript made him aware of how his writing had developed since August 1910: ‘I was so young – almost pathetically young – two years ago’ (1L 344). His rate of progress with the revisions can be gauged by the fact that he had only just completed the first chapter by 3 January, but by 29 January was ‘past the 300th page’ (1L 358) and looking to finish it during the following week. He wrote to Helen Corke to make her aware that he planned to publish the ‘Saga’ in its revised form, and he offered to send her the manuscript to set her mind at rest about the changes (though she never actually got to see it).54

After he left Bournemouth, on 3 February, Lawrence went to spend a week with Garnett at the Cearne before travelling to Eastwood, where his sisters could provide him with a temporary home. He was now forced to think about his plans for the immediate future. At Bournemouth he had entertained the idea of going abroad: a German cousin, Hannah Krenkow, had invited him to visit her in Waldbröl, near Cologne, and he considered taking up the offer in the spring. He also had to confront his changed feelings for Louie. According to a note written by Louie after his death, at some point following his illness Lawrence proposed that they should marry straight away (in January 1912), and Louie accepted the offer.55 Any such proposal would most likely have been made in Croydon in late December or during their few days together at Redhill; it would have been made on impulse, in the face of mixed feelings, and under the influence of Louie’s presence. The intervening time for reflection – and the opportunity to confide his feelings to Garnett – underscored his need to break from his past, and from the notion of settling down to a comfortable married life as a teacher.

The day after his arrival at the Cearne he wrote a letter to Louie breaking off their engagement. The letter was carefully phrased and decisive, providing sound reasons why he should not marry, but it also made it clear that he did not wish to do so. He cited ‘what the doctor at Croydon and the doctor at Bournemouth both urged on me: that I ought not to marry at least for a long time, if ever,’ but he also told her that illness had changed him ‘a good deal,’ breaking ‘a good many of the old bonds that held me’ (1L 361). The change in his character was confirmed by Ada in a letter she sent to Louie 12 days later; in it, she claims that he is ‘changed for the worse’ and refers to ‘his flippant and really artificial manner.’ Even allowing for the likelihood that Ada exaggerated Lawrence’s state of mind in order to ease the blow for Louie, the strength of her expression is striking: she told Louie that she ‘wouldn’t marry a man like him, no, not if he were the only one on the earth.’56 It is possible that Lawrence had said unpleasant things about Louie to Ada while she nursed him through the worst of his illness back in late November; she may also have learnt about his relationships with Helen Corke and Alice Dax. Louie’s response to the letter was to ask Lawrence to reconsider, and to reply by telegram. Instead he wrote a brief note confirming his determination to end things: ‘I do really feel it would be better to break the engagement. I dont think now I have the proper love to marry on’ (1L 363).

The sense of freedom and relief which accompanied his decision to break with Louie precipitated an immediate appeal to Helen. His intense imaginative re-engagement with The Trespasser would have meant that she had been occupying his mind fairly constantly during the past month. The day after he had sent his first letter to Louie, Lawrence wrote to Helen, asking whether she could meet him one evening on Limpsfield Common, so that they could walk down to the Cearne together. He suggested that she ‘might stay the night, if you would consent’ (1L 362). Lawrence was alone with Garnett in the house, and he assured her of his host’s broad-mindedness and tact. Helen, however, refused to fall in with his plans. Lawrence finished revising The Trespasser during his stay with Garnett; he left the manuscript at the Cearne when he departed for Eastwood on 9 February (he visited Hueffer and Violet Hunt en route, attending a matinee performance of plays by J. G. Adderley, Yeats and Lady Gregory at the Royal Court Theatre).

Life at his elder sister Emily’s house in Queen’s Square during the next three months would be quite claustrophobic after the freedom of Bournemouth and the visit to Garnett: he would be living with Emily, her husband Sam King, their young daughter Margaret (‘Peg’), plus Ada and their father. The first days were eventful: on the day of his arrival there was a party to celebrate Peg’s third birthday, then in the next few days Lawrence arranged a number of meetings. He wrote to Jessie and went to see her at her new lodgings in Nottingham (she was teaching at Musters Road School): his attention had now returned to ‘Paul Morel’, so he would have wanted to collect the notes on their youth which he had asked her to produce for him, and which she had continued to write during the period of his illness.

Then, on 13 February, he met Louie in Nottingham. Lawrence told Garnett that she was stern and aloof, though her own (conflicting) account stressed how Lawrence ‘was already in evening clothes & kept his overcoat buttoned up,’ while she was ‘dumb with misery.’57 The following day he arranged to see Alice Dax; in the letter to Garnett he describes a ‘sequel’ to his meeting with Louie ‘which startled me’ and could not ‘be committed to paper,’ and he refers to his meeting with Alice as ‘another rendez-vous’ (1L 366), which strongly suggests that he had succumbed to the sexual attraction he felt for Alice back in March 1910. The intensity of her feelings for him at this time (and in the preceding months) were such that she later claimed to have conceived her second child (her daughter Phyllis Maude) under their influence.58 Lawrence seems, however, to have taken a far more detached approach to the affair. During a party he attended on 24 February with Ada at Jacksdale, a ‘mining village four miles out,’ he disgraced himself by ‘kissing one of her friends goodbye’: he told Garnett that ‘life is awfully fast down here’ (1L 369). Four days later he wrote to the Croydon Education Committee to resign from his teaching post; it would have given him particular satisfaction in light of the anger he felt about the money they had deducted from his December wages, on account of his long-term absence.59 Agnes Mason delivered a leaving gift of two books to him on 9 April (one of them was a volume of Chekhov’s plays).60

It is revealing that Lawrence’s return to the place of his youth only intensified his feelings of emotional unrest and rootlessness. His plan to travel to Germany in the spring would have allowed him to think of his stay in his sister’s house as a brief interlude, rather than any more permanent arrangement. Then again, daily life in Eastwood was disrupted by the national disputes over miners’ wages which had been ongoing since early February. On 26 February the miners came out on strike; their industrial action would last through until 6 April (Lawrence went out to deliver relief tickets to badly affected families on 2 April).61 Between mid-February and 17 March, Lawrence wrote four fictional sketches based on the industrial unrest and the strike: ‘The Miner at Home’, ‘A Sick Collier’, ‘Her Turn’ and ‘Strike-Pay’. Garnett seems to have encouraged him to write them: Lawrence had little enthusiasm for the task, though he worked to make them as ‘journalistic’ (1L 376) as he could. They concentrate on the camaraderie between the striking miners, their anxiety about money, and the anger and resentment of the wives and mother-in-laws (who are forced to run their houses, and care for their children, on reduced money). The sketches demonstrate Lawrence’s ability to record what he now saw around him with an insider’s understanding but an outsider’s interest and attention to detail. Garnett immediately managed to place one of the more documentary pieces (‘The Miner at Home’) in the Nation; it was published on 16 March. Other sketches were sent, with no success, to The Daily News and The Eyewitness.

Lawrence relied heavily on his existing contacts to help him out in negotiating with publishers and journal editors. Garnett continued to be very attentive to Lawrence’s literary affairs: his support was crucial in securing Duckworth’s agreement to publish The Trespasser (Lawrence corrected proofs in early April, waging further war on the novel’s adjectives).62 Garnett also managed to exploit topical interest in the miners’ strike to involve the actor and producer Ben Iden Payne in negotiations with Lawrence for the staging of one of Lawrence’s plays.63 Walter de la Mare acted on Lawrence’s behalf in forwarding some of his poems to John Alfred Spender, editor of the Saturday Westminster Gazette (which published a sequence entitled ‘The Schoolmaster’ in four consecutive weekly numbers between 11 May and 1 June).64 Then there was Austin Harrison, from whom Lawrence sought support (he had agreed to publish the poem ‘Snap-Dragon’ in the June number of the English Review, though he was irritated by Garnett’s involvement in Lawrence’s dealings with the journal).

During this period of change Lawrence settled to work again on ‘Paul Morel’. He rapidly transformed the incomplete second draft of the novel into something close to the version we now know as Sons and Lovers, incorporating into the early chapters the same rich descriptions of mining life which he put into the sketches. He passed on his work to Jessie as he completed it: she was initially delighted that he was including the realistic detail which she had felt was missing from the previous draft, but in time she would be dismayed and finally devastated by the version of their relationship he presented through the characters of Paul Morel and Miriam Leivers, and by what she saw as the betrayal implicit in his failure to describe their early intellectual kinship. At some point in March he started to post his work to Jessie rather than meeting with her to discuss it in person.

(x) Frieda

In early March something happened which would completely transform Lawrence’s life, helping to cut him free from the past at the very point when he was working so hard to safeguard his future. His aunt and uncle, Ada and Fritz Krenkow, had been instrumental in urging Lawrence to spend some time in Germany in the spring. They now encouraged him to explore his chances for employment there, perhaps as a schoolteacher or a lecturer (since they lacked confidence in his ability to support himself as a writer). It seems likely that they took the initiative in arranging for Lawrence to speak with Ernest Weekley, Professor of Modern Languages at Nottingham University College, and one of the two tutors whom Lawrence had admired during his time as a student. Weekley was perfectly placed to advise Lawrence, since he had briefly held a post as Lektor in English at the University of Freiburg before taking up his current position at Nottingham in 1898.

Weekley invited Lawrence to lunch at his house in Private Road, Mapperley, on Sunday 3 March. Lawrence had initially planned to visit Alice and Harry Dax in Shirebrook that weekend,65 and was in any case uncertain about the value of meeting with Weekley to discuss teaching, so he initially turned down the invitation. However, when the offer was repeated by Weekley’s German wife, Frieda, he accepted and put off his visit to the Daxes until the Sunday evening or the following day. In any case, when he arrived at the Weekleys’ house in the late morning on that warm Sunday, Weekley was not at home and Lawrence, in his best clothes, was shown in to the sitting-room by his wife. Their three children, Montague or ‘Monty’ (aged 12), Elsa (10) and Barbara or ‘Barby’ (eight) were playing in the garden, visible through the open doors of the French windows. Frieda and Lawrence had half an hour together before her husband arrived: they spoke animatedly about Oedipus and women (Frieda was ‘amazed at the way he fiercely denounced them’).66 We do not know what was said over lunch, but Lawrence never seriously considered teaching as an option when he was in Germany; he did not see Weekley again. It was the beginning, however, of his lifelong relationship with Frieda.

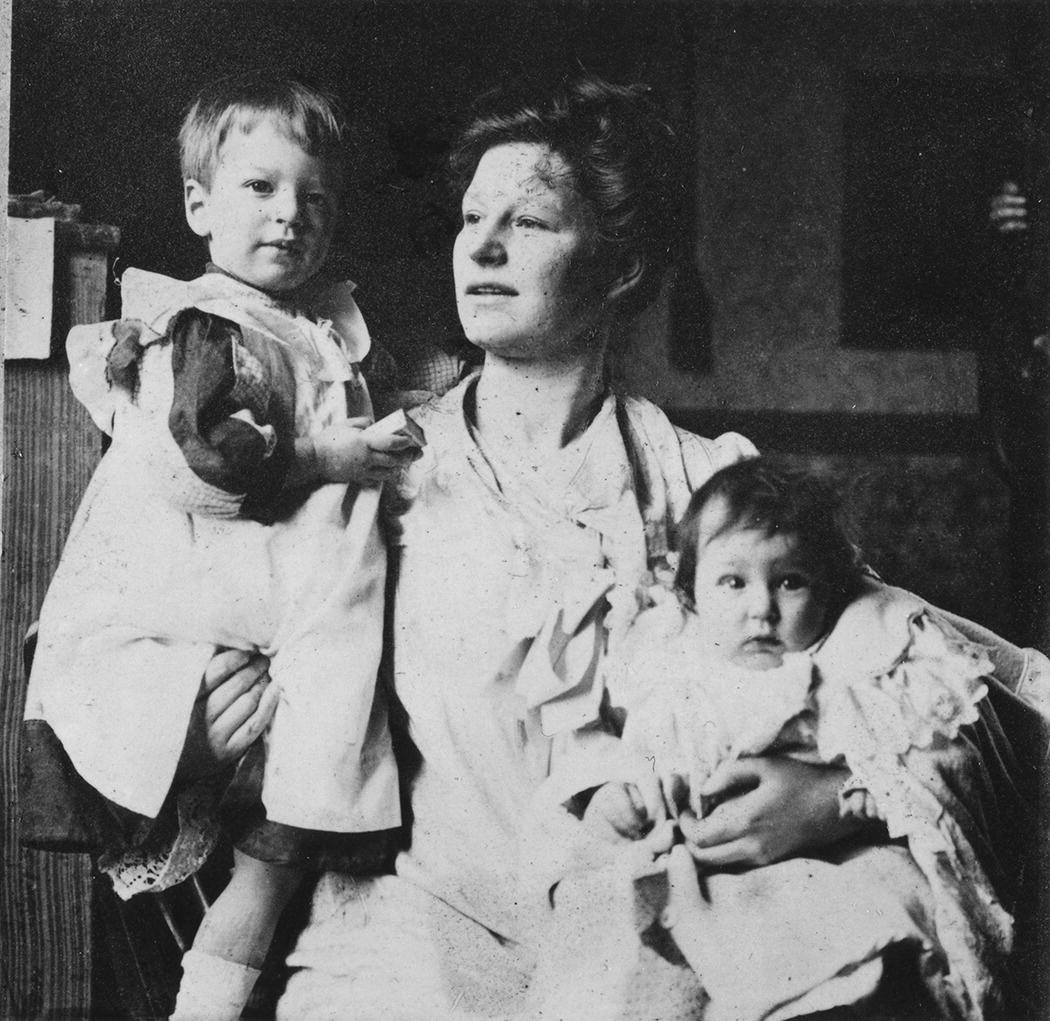

Figure 5 Frieda Weekley with two of her children, Monty and Barbara, Nottingham, c.1905. (Manuscripts and Special Collections, The University of Nottingham, La We 6/2.)

That afternoon he visited the Chambers family at their farm in nearby Arno Vale, and shortly afterwards he travelled to Shirebrook to spend a few days with the Daxes. Although any relationship with Frieda would have seemed impossible for him at that time, he was immediately taken with her beauty and the unflinching courage and intelligence he had detected in her during their brief meeting; within hours of seeing her he told Jessie that it would do her good to know Mrs Weekley.67 He might have sensed, even at this early stage, that Jessie’s strong moral sense and stubborn commitment to the experiences they had shared in the past would be helpfully offset by Frieda’s outspokenness and willingness to challenge his resentment of women. He did not yet know how Frieda’s background and marriage had nurtured her vivaciousness.

Frieda was the second of the three daughters of Friedrich von Richthofen, a former army officer who had been injured in the Franco-Prussian War and now had a reserve commission, working as a civil engineer in the fortified city of Metz. Lawrence told Garnett that Frieda’s father was ‘Baron von Richthofen, of the ancient and famous house of Richthofen’ (1L 384), though Friedrich and his wife Anna were more gentry than aristocracy (his family had fallen on hard times as a result of a series of farming disasters). Frieda’s parents were badly matched, and her father had taken to gambling and womanising; her own marriage to Ernest Weekley in Freiburg in 1899 (at the age of 20) gave her a kind of stability which she had never had from her parents. Weekley was 14 years her senior and a serious, and gifted, scholar who had worked his way up from a modest background to attain a strong academic reputation and middle-class respectability: he had taken an external degree at the University of London before winning a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, to study Middle English and modern languages, and had spent time at the Sorbonne before moving to Freiburg. Frieda led a comfortable existence in Nottingham: she had, for example, a German nurse (Ida Wilhelmy) for her three children, and the family home was very substantial, located in a quiet suburb to the north of the city. She had some limited opportunity to contribute to her husband’s academic pursuits, too, preparing a small edition of Schiller’s verse and a volume of German fairy tales for pupils of German, and helping one of Ernest’s colleagues to translate W. B. Yeats’ play The Land of Heart’s Desire into German.68 Yet her sexual relationship with her husband had been disastrous from the start, and she often felt lonely and dissatisfied with the routines and values of provincial English life. Like her sisters, Else and Johanna (or ‘Nusch’), she had taken lovers to alleviate her boredom: since 1907 she had had affairs with three men, in both Germany and England (the Nottingham lace manufacturer William Enfield Dowson, the Austrian psychoanalyst Otto Gross, and the Swiss painter Ernst Frick).69

Lawrence seems to have known almost immediately that he loved Frieda (and that he loved her enough to want to marry her). Within a week of meeting her, he sent her a note saying ‘You are the most wonderful woman in all England’ (1L 376). She responded in a robust manner: ‘You don’t know many women in England, how do you know?’70 Frieda was six years older than Lawrence, and far more sexually experienced and pragmatic about relationships. Yet the attraction between them was obvious, and she soon began to reciprocate his feelings. Meeting was difficult, but it could be managed with careful planning. He made occasional visits to Private Road; they went to the theatre together in Nottingham, to see Shaw’s Man and Superman; and they went together with Frieda’s daughters to visit May and Will Holbrook at their cottage in Moorgreen. Lawrence’s ability to lose himself in imaginative games with the children stayed in Frieda’s memory for the rest of her life. She particularly recalled an occasion when he took her and her two daughters for a walk in Sherwood Forest. He floated daisies face upwards in a fast-flowing brook, and then made paper boats, filling them with burning matches to re-enact the defeat of the Spanish Armada. The girls were in ‘wild excitement’ at having ‘such a play-fellow.’ Frieda recalled how it was at this moment that she felt a different kind of ‘tenderness’ towards him that she had ‘not known before.’71

Around their meetings Lawrence found time to go on seeing old friends like George Neville, whom he visited at his new home at Bradnop in Staffordshire from 25 to 31 March. On 8 March Lawrence was shocked to learn that Neville had got married in secret back in November to a girl who was already heavily pregnant.72 Neville had already fathered one illegitimate child; this time he had been dismissed from his teaching post in Amblecote on the back of the ensuing scandal and moved to another school near Leek. His new wife was living with their child at her parents’ house, some 50 miles away in Stourbridge. Lawrence was evidently amused by the scrape that Neville had got himself into. On his return from the visit, he wrote a play based on his old friend’s unenviable situation: it was a ‘comedy – middling good’ (1L 386) entitled The Married Man. It is notable for containing Lawrence’s first fictional portrayal of Frieda: the role of Elsa Smith is to introduce a healthy blast of amorality into proceedings, telling Sally Grainger (the outraged wife of the philandering Neville-figure, Dr Grainger) that she should stay with her husband, since it is perfectly possible for him to have affairs with other women and still retain all his love for his wife.