6

‘The Real Fighting Line’: August 1914–December 1915

(i) Nightmare

The war affected Lawrence very deeply from the moment he heard of its declaration. He told Edward Marsh: ‘I don’t see why I should be so disturbed – but I am. I can’t get away from it for a minute: live in a sort of coma, like one of those nightmares when you can’t move’ (2L 211). In one sense, of course, his connections with Germany and his marriage to Frieda meant that he was more closely touched by the conflict than he might otherwise have been. Soon after 9 August, he wrote a short but remarkably prescient article entitled ‘With the Guns’, in which he placed his experience of seeing the English soldiers waved off at Barrow railway station alongside his witnessing of military manoeuvres in Bavaria in autumn 1913. Lawrence warned that this would be ‘a war of artillery, a war of machines, and men no more than the subjective material of the machine’ (TI 84). The piece was published in the Manchester Guardian on 18 August. He and Frieda heard of losses on both sides (including the early death of Udo von Henning on 7 September);1 they were able to see behind the propaganda in the newspapers and contested the opinions of friends, even while they became subject to the spread of anti-German sentiment.

The hostilities exposed them to public suspicion, but war also threatened Lawrence’s ability to support himself through his writing. Just days after his return to London, he learnt that Methuen had returned the typescript of ‘The Wedding Ring’ to Pinker; the company had responded to the outbreak of war by suspending all new projects for six months, which entailed the withholding of royalties. Lawrence had spent money freely on the understanding that his receipt of the second half of his advance – the second instalment of £150 – was imminent. He was plunged into financial difficulties. The most pressing problem was to find somewhere to live, since he and Frieda could not go on staying rent-free in Gordon Campbell’s house. Fortunately, one of their new friends, Gilbert Cannan, helped them to find a small cottage (‘The Triangle’) near Chesham, Buckinghamshire, at the cost of just six shillings per month. The Lawrences moved in on 15 August. It was ‘tiny, but jolly’ (2L 208). There was only one bed, so Lawrence was forced to get a camp bed in order to accommodate guests; he set about cleaning and whitewashing the place. He and Frieda had grown accustomed to moving and creating new homes since they had first left England in May 1912: they were resourceful and skilled at surviving on little money.

Their first instinct, as always, was to invite people to visit them. Lawrence wrote to Amy Lowell to establish which of his poems she wished to include in Some Imagist Poets (1915); he almost begged her to drive the 30 miles ‘to Chesham, through Harrow’ (2L 209). Kot and Edward Marsh also received invitations, and Lawrence cultivated new bonds through his contacts (notably with the painter Mark Gertler, who was a close friend of the Cannans, and with Francis Birrell, a friend of David Garnett). John Middleton Murry and Katherine Mansfield came to stay between 14 and 26 October: Lawrence helped them to plaster and paint their own new cottage near Great Missenden, a short distance from Chesham.2

People began to rally around Lawrence once they became aware of the extent of his financial predicament. Marsh was particularly generous: he sent more money to Lawrence for his contribution to the first volume of Georgian poetry, plus a cheque for £10 which moved Lawrence ‘almost to tears’ (2L 213). Mary Cannan informed some of her contacts about Lawrence’s troubles, which resulted in a further cheque for £10 from the dramatist and translator Alfred Sutro. Lawrence was encouraged to apply for relief to the Royal Literary Fund: with the support of Maurice Hewlett (a novelist, poet and essayist), A. E. W. Mason (a novelist and playwright), Harold Monro, Marsh and Gilbert Cannan, Lawrence was awarded a payment of £50 in October.3 In contrast, an application to the Society of Authors came to nothing, much to Lawrence’s disgust.4 Lawrence was certainly willing to accept financial support, but he was very sensitive to any suggestion of charity or condescension: Amy Lowell (once she was back home in America) got around this by sending him a typewriter, which he received in early November.5

Pinker had helped Lawrence by placing ‘Honour and Arms’ with Metropolitan magazine in America for £25. Lawrence was keen, however, to wrest back a duplicate typescript of ‘The Wedding Ring’ from Mitchell Kennerley. Back in May a cheque which Kennerley had sent to Lawrence in part settlement for the American publication of Sons and Lovers had bounced; Lawrence had returned it to him, and the publisher’s failure to respond now became a cause of anger and frustration.6

In the midst of so much upset and uncertainty it was important for Lawrence to keep busy. In late August, Frieda had the idea of translating The Widowing of Mrs. Holroyd into German.7 Meanwhile, on 5 September Lawrence began writing his book about Thomas Hardy, out of ‘sheer rage’ at the war. Swift completion of the short book would have secured a very welcome payment of £15, but Lawrence (with his penchant for reading against the grain of authors) was never likely to toe the series line: he soon recognised that his book would be ‘about anything but Thomas Hardy … queer stuff’ (2L 212). Like the ‘Foreword’ to Sons and Lovers, the so-called ‘Study of Thomas Hardy’ – which Lawrence wanted to call ‘Le Gai Savaire’ after Nietzsche’s Die fröhliche Wissenschaft (1882–1887)8 – became an unpublishable vehicle for his impassioned critique of English culture. It identified in Hardy’s novels a conventional commitment to social morality and the cause of the weak and kind-hearted, but it also explored Hardy’s more compelling imaginative fascination with passion and lawlessness (through demonised characters like Sergeant Troy, Alec D’Urberville and Arabella Donn). Safety and risk, Love and Law, become the binary terms in a quasi-philosophical treatise which reads the war spirit in England as a mass reaction against a negative form of society based on self-preservation. Lawrence identifies destruction and self-destruction as the only available means of self-realisation for the allied soldiers on the battlefield.9

This view of soldiers as helpless beings unconsciously drawn to violence was bound to appal a good many people in Britain during war-time. Lawrence was convinced of it; indeed, his understanding of soldiers and their motivations only darkened as the war progressed. It was during early October that Lawrence first grew a beard: this was partly because of illness, but his refusal to shave also became a sign of his difference and of his status as a radical and outsider. His anger about the war found expression in tirades: he had to apologise to both Catherine Jackson and Kot for the intensity of his outbursts in late October and mid-November.10 Lawrence blamed the meaninglessness of civilian life in England for creating suicidal impulses in the soldiers. During the first months of the war he was inclined to draw comparisons between marital conflict and the fighting in Flanders; when proofs of his new collection of short stories for Duckworth began to arrive in October, he suggested to Garnett that it might be called ‘The Fighting Line’, since ‘this is the real fighting line, not where soldiers pull triggers’ (2L 221). Garnett, however, re-named ‘Honour and Arms’ ‘The Prussian Officer’ and made that the title of the volume, too, when it was published on 26 November, identifying its topicality, and the story’s depiction of German military sadism, as potential selling-points; Lawrence thought him ‘a devil’ (2L 241) for doing so. When Lawrence received the special ‘War Number’ of Poetry on 17 November, courtesy of Harriet Monroe, the ‘glib irreverence’ (2L 232) of its contributors made him so furious that he tapped out his own war poem in response, on his new typewriter. The surviving sections of an early version of this poem, entitled ‘Ecce Homo’, show how Lawrence sought to offset the voyeurism and aestheticising blandness of several of the contributions by writing from the perspective of a soldier immersed in combat and utterly unable to distinguish ally from enemy.11 A letter he wrote shortly afterwards to Amy Lowell suggests that he was alert to the difficulties Americans might face in properly comprehending the immersive reality of a European war: ‘The war-atmosphere has blackened here – it is soaking in, and getting more like part of our daily life, and therefore much grimmer’ (2L 234).

(ii) Fantasies of escape

Lawrence and Frieda had always planned to return to Italy in the autumn; even at the end of the year they clung to the idea of going back to Fiascherino (Frieda gave their old Italian address to Amy Lowell on 18 December in anticipation of their return).12 They drew a network of friends around them in Buckinghamshire and London, but the feeling of entrapment and powerlessness created obvious tensions. Lawrence’s anger at Kennerley tended to be expressed towards Frieda; for her part, Frieda still pursued the goal of gaining access to her children. In late November, just as Lawrence put the finishing touches to his book on Hardy and began revising ‘The Wedding Ring’, she decided to visit Nottingham to try to speak with Weekley in order to secure his permission for visits. Lawrence travelled with her: they stayed with Ada in Ripley between 6 and 10 December. The meeting was a disaster. Frieda gave a false name to the maid in order to gain admittance to the house: Weekley was infuriated by the intrusion and threatened her with legal action.13

It was hardly an ideal opening to the Christmas period. Yet, Lawrence was in bullish mood coming into the festivities. His revision of ‘The Wedding Ring’ was progressing well; he soon came to enjoy working on it and sending it on in batches to Pinker. He had sent the Hardy book to Kot for typing. Its diagnosis of the state of English society, and its spirit of opposition to the war, show how he now perceived his writing as a means to question the accepted forms of society: it was the job of literature in war-time to irritate, provoke and subvert. Kot warned him that the critics would ‘beat’ him over his book on Hardy, but Lawrence took his friend’s wariness as a good sign. He proudly announced to Amy Lowell that The Prussian Officer and Other Stories was not doing very well: ‘The critics really hate me. So they ought’ (2L 243). He had argued that Sons and Lovers was written to change the perceptions (and the lives) of young Englishmen like Bunny and Harold Hobson; the war made his message all the more urgent. Lawrence hoped that there would be a revival of interest in serious novels: he told Pinker that war would ‘[kick] the pasteboard bottom in the usual “good” popular novel’ and would bring about a ‘slump in trifling’ (2L 240).

On Christmas Eve, the Lawrences invited Gordon Campbell, Kot, Murry, Katherine Mansfield, Mark Gertler and the Cannans to ‘The Triangle’ for a party. Lawrence asked Kot to bring along two flasks of Chianti; they would drink them ‘in memory of Italy’ (2L 243). Lawrence made rum punch and Frieda produced marzipan: they all sang and danced. The next day the group went for dinner with the Cannans. This time they acted out small plays and mimicked music-hall sketches; the revelry was not without its tensions, however, since Murry and Katherine Mansfield were encountering real difficulties in their relationship and the conflict showed through in their performances.14

On 3 January, Lawrence sent a cheery letter to Kot containing his first reference to ‘Rananim’. Roughly based on his friend’s yuletide rendition (in Hebrew) of the first line of Psalm 33 (‘Rejoice in the Lord, O ye Righteous’), ‘Rananim’ was a term Lawrence used as a form of shorthand to describe a small community of friends with whom he might set up a selective ‘Order’ in the face of a hostile world. It was a way of commemorating the precious feeling of camaraderie he had felt at Christmas, but it was also a fantasy to offset the reality of the war and the growing feeling of isolation in his small cottage: it has been called ‘a kind of complex, private game, played by people who felt trapped in England.’15 The very different terms in which Lawrence described the concept to his friends, and the wholesale transformation of the small community idea over several years, points to its central role as a way of asserting the bond of friendship through shared ideals. He told Kot that its motto would be ‘Fier’ (‘Proud’); two days later, he responded to Lady Ottoline Morrell’s praise of The Prussian Officer by telling her that he wanted ‘the appreciation of the few’ and that ‘life is an affair of aristocrats’ (his personal motto would be ‘Fierté, Inégalité, Hostilité’ [2L 254]). He had met Ottoline (the titled daughter of Lieutenant-General Arthur Cavendish-Bentinck and Lady Bolsover) at a party she gave at her house in Bedford Square back in August, shortly before his move to Buckinghamshire. On 18 January, Lawrence described his ‘pet scheme’ in rather different terms to his old Eastwood socialist friend Willie Hopkin: ‘I want to gather together about twenty souls and sail away from this world of war and squalor and found a little colony where there shall be no money but a sort of communism as far as necessaries of life go, and some real decency’ (2L 258).

It would be easy to dismiss these declarations as politically naïve, or even opportunistic. However, we get closer to the spirit of the utterances if we attend instead to the contradictions which lie at the heart of Lawrence’s idea of ‘community’. These rest largely on his changing understanding of his war-time readership. At times he believed that his writing could appeal in a vital way to a common humanity and help individuals through to a new understanding of self, society and sexuality; at others, he despaired of ever being understood and became belligerent, aloof and haughty in order to ward off his feeling of rejection and isolation. Lawrence thought of himself, at different times, as inside and outside the camp: as coaxing and encouraging, and as hurling abuse from the sidelines. Both stances would take their place in his great war-time writings.

(iii) ‘Coming into my full feather’

As he worked at turning ‘The Wedding Ring’ into The Rainbow, Lawrence retained a very firm belief in his ability to transform his readers. His ambition was to reveal the historical and psychological shifts – religious and scientific – across three generations of the Brangwen family, in order to explore areas of continuity and change in male and female experience. From late November he had worked in particular on the first two generations of the novel, fleshing out the Tom/Lydia and Will/Anna relationships to trace a family line of courageous independence and female rebellion through to the trail-blazing and decidedly modern Ursula Brangwen (he had changed his heroine’s name from ‘Ella’). The addition of a good deal of new material – including Will and Anna’s visit to Lincoln Cathedral – allowed Lawrence to dramatically explore the conflicts in relationships, and to develop an elaborate and complex series of symbolic patterns and correspondences.16 He was helped in this by his reading of Katherine L. Jenner’s Christian Symbolism (1910). The additions meant that by 7 January he had decided to split his novel in two, keeping the later material (including his heroine’s relationship with Birkin, and Gudrun’s relationships with Gerald and Loerke) for a further volume.17 It would eventually form the basis of Women in Love. He was surprised by the extent of his own revisions, and he worried that Methuen might complain about the new version and ‘wonder what changeling is foisted on him,’ but he told Arthur McLeod that he was ‘coming into my full feather at last’ (2L 255).

Lawrence came down with a troublesome cold early in the new year of 1915. He was struggling with the cold, damp, cramped conditions at ‘The Triangle’; he grew to hate it in the darkness of winter. Catherine Jackson (shortly to marry Donald Carswell) found Lawrence miserable during a visit she made, ‘holding on to himself against depression’;18 she evidently told her friend Viola Meynell (daughter of Alice, the poet and essayist) about Lawrence’s plight, since Viola invited him to live rent-free at her cottage in Greatham, Pulborough, Sussex. The cottage was one of several renovated by Viola’s father Wilfrid for his three daughters (Monica, Madeline and Viola) on their 80-acre family estate. Lawrence was initially a little perturbed by the prospect of living amid ‘the whole formidable and poetic Meynell family’ (2L 255), but he gratefully accepted the offer. He and Frieda left ‘The Triangle’ on 21 January and spent two days in London, staying with David and Edith Eder in Hampstead. On the day of his departure he had lunch with Ottoline Morrell and tea with Edward Garnett. He went back to Ottoline’s house for dinner with E. M. Forster and David Garnett; Duncan Grant, Mark Gertler and Dora Carrington joined the party afterwards. The following day, Lawrence accompanied Forster to Grant’s studio, to see some of his paintings. He hated what he saw and was vocal in his criticisms: to Ottoline he complained of Grant’s ‘silly experiments in the futuristic line’ (2L 263). It was an inauspicious introduction to Bloomsbury aesthetics.

On the evening of 23 January, Lawrence and Frieda were taken by car to their new home. En route they sent a little blue plate with a dragon design to Catherine – now Mrs Carswell – as a wedding gift and a token of their affection.19 The cottage was ‘rather splendid – something monastic about it – severe white walls and oaken furniture – beautiful’ (2L 261). Unlike ‘The Triangle’, it boasted a bathroom and two spare bedrooms, so friends could be accommodated quite easily. Nestling ‘at the foot of the downs’ (2L 269), it gave the Lawrences access to open countryside, and to the coast at Littlehampton. After Buckinghamshire it felt like a form of re-birth from the nightmare of the past few months.20

Lawrence was soon able to get back to work on The Rainbow; Viola Meynell agreed to type it for him. Ottoline Morrell came down for the day on 1 February; Lawrence appreciated her support, and her social connections made her the perfect person to involve in his ‘Rananim’ idea. He felt that she might ‘form the nucleus of a new community which shall start a new life amongst us’ (2L 271). There was a very practical element to her involvement. Ottoline suggested, for instance, that the Lawrences could move to a cottage she was planning to build in the grounds of Garsington Manor in Oxfordshire (a property which she had bought two years before, but would only move into in May 1915, once the current tenants had left); like Katherine Mansfield, Ottoline was recruited by Frieda to help her gain access to the children (Lawrence felt that her social status might impress Weekley and make him co-operate). Unfortunately, neither plan came to anything.

In Greatham, the ‘Rananim’ idea went from being a fantasy about community to a plan for ‘social revolution’. Again and again in letters to friends, Lawrence argued for a change in the fabric of life, addressing an over-reliance on money by ensuring the equal distribution of basic necessities: ‘Private ownership of land and industries and means of commerce shall be abolished – then every child born into the world shall have food and clothing and shelter as a birth-right, work or no work’ (2L 292). On 8 February, Ottoline brought her lover, the celebrated Cambridge philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell, to visit Lawrence; although Lawrence was initially rather alarmed and intimidated by the prospect of the visit, the two men got on well. Russell was so impressed by Lawrence’s powers of psychological insight that he thought him ‘infallible … like Ezekiel or some other Old Testament prophet.’21 Lawrence used Russell as a sounding-board for his ideas of revolution; he planned to visit Russell in Cambridge in early March to think of ways in which they might collaborate, though he was also intensely aware that Russell’s world and language were in some sense closed to him.22 Russell would need to come over to Lawrence’s world if they were to work together: the gulf between his political pacifism and Lawrence’s religious idealism would soon be starkly exposed.

Other possible candidates for the revolution also visited the Lawrences. E. M. Forster sent Lawrence copies of Howards End (1910) and The Celestial Omnibus (1911), and then came to stay between 10 and 12 February. After a lively enough start, the visit proved awkward. Forster had decorously retreated from Lawrence’s critical outburst in Duncan Grant’s studio, and he was willing to accept Lawrence’s harsh judgement of his novel and short stories, but he baulked at having his character and sexuality dissected at length in his host’s cottage. He subsequently sent Lawrence an outspoken letter stating his dislike of ‘the deaf impercipient fanatic who has nosed over his own little sexual round until he believes that there is no other path for others to take.’23 Lawrence liked Forster, but found his life ‘ridiculously inane’; he told Mary Cannan that Forster ‘was very angry with me for telling him about himself’ (2L 293). Forster particularly objected to being addressed by the ‘firm’ (2L 277) of both Lawrence and Frieda: he was not alone in finding aspects of Frieda’s behaviour, and Lawrence’s insistence on her central role in his creative life, distasteful (Murry and Kot both had their reservations). It took a particular kind of person to bear with Lawrence’s forceful ideas and to fall in (or appear to fall in) with his schemes. Forster gracefully withdrew; Gordon Campbell had an altogether more personal and mystical understanding of religion which Lawrence found uncongenial;24 and Cynthia Asquith, who visited from 16 to 17 February, was found to be unsuitable.25 Murry was the great hope: he came to stay with Lawrence for a week from 17 February, and was nursed by him after coming down with flu following Katherine Mansfield’s departure for Paris to spend time with Francis Carco.26

On 2 March, Lawrence finished The Rainbow; by the middle of the month he was revising the typescript as it came back from Viola Meynell. This was a process that would continue through to the end of May. Lawrence now sought to redress the balance between Will and Anna in the second generation of the novel, making Anna equally culpable for the conflict between them. In early April Lawrence sent a first batch to Ottoline, asking for her opinion of it. Two further batches would follow. Viola’s typing was very slow (she eventually needed to seek assistance from Eleanor Farjeon), and Pinker was impatient; it was not until 31 May that Lawrence could send the final typescript pages directly to him, asking him to dedicate the novel in Gothic script ‘Zu Else’ (in honour of his sister-in-law). It was not the kind of request which a publisher could have acceded to in 1915: Lawrence had to agree to the dedication appearing in normal type and in English.27

(iv) ‘Philosophicalish’

After finishing his novel in early March, Lawrence turned straight back to his philosophy. The short book on Hardy – ‘mostly philosophicalish, slightly about Hardy’ (2L 292) – had developed beyond the terms of the commission; it was unusable, so Lawrence decided to re-write it and publish it in instalments in a pamphlet as a kind of manifesto or call to arms. At various points the re-written philosophy, or ‘Contrat Social’ (2L 312), was entitled ‘The Signal’, ‘the Phœnix’ and ‘Morgenrot’;28 it finally became ‘The Crown’. It moved on from the earlier focus on self-realisation in the ‘Study’ to examine in despairing mood the kinds of self-containment, self-hatred and immersion in destruction which Lawrence saw around him (in the maimed soldiers returning from the Front, and in the men and women left behind and hopelessly attracted to the glamour of violence).

Over the course of its composition, between March and October, ‘The Crown’ drew in (and analysed) various experiences which confirmed Lawrence’s sense of general disintegration in war-time England. Two negative events during March and April were soon incorporated into his philosophy. From 6 to 8 March Lawrence visited Russell in Cambridge. He expressed some trepidation about the visit beforehand, fearing that he would be ‘horribly impressed’ (2L 300) and that he would be found to speak ‘a little vulgar language of my own’ (2L 295). In fact, although he got on rather well with Russell, and enjoyed talking with the mathematician Godfrey Harold Hardy, he hated Cambridge. One event particularly troubled him. Russell took him to visit the economist John Maynard Keynes late one morning in his rooms at King’s College. Thinking Keynes absent, Russell had begun to write a note for him, when the door opened and ‘K. was there, blinking from sleep, standing in his pyjamas.’ Lawrence felt ‘the most dreadful sense of repulsiveness – something like carrion’; he said that it made him feel ‘insane’ and dream of beetles. The same feeling was reactivated on the weekend of 17 and 18 April, when David Garnett brought Francis Birrell and William MacQueen to Greatham. Lawrence detected in Birrell a ‘form of inward corruption’ (2L 320–1); it made him dream of ‘a beetle that bites like a scorpion. But I killed it – a very large beetle’ (2L 319). He wrote to Bunny to warn him off from further involvement with Birrell, telling him to go away ‘and come to your real self’ (2L 322).

As always in Lawrence, the strong, emotive language which he used to describe these experiences – ‘horror’, ‘decay’, ‘corruption’, ‘frowstiness’, ‘repulsiveness’, ‘wrongness’ – indicates a very conscious desire to grasp and make sense of his feelings; it is not simply a case of visceral recoil from something unspeakable. It would be reductive, therefore, to see the disgust he expresses as a straightforward symptom either of his own repressed homosexuality or of a hatred of homosexuality in others. Lawrence’s letters to Henry Savage had revealed his conviction that all humans are to some extent bisexual; he makes it clear in the letter to Bunny that he does not consider homosexuality ‘wrong’, and he does not ‘speak from a moral code’ (2L 320–1). It is his assumption about the attitudes of Keynes and Birrell that horrifies Lawrence. In ‘The Crown’, he would diagnose (and deplore) in the wider culture a kind of predatory voluptuousness which he considered wholly repulsive, reducing other people to objects of use.

A visit to Worthing on 29 April only confirmed Lawrence’s sense of the country’s immersion in violence and destruction. He saw many soldiers on the sea-front: they reminded him of ‘insects – one insect mounted on another.’ In a letter of 30 April to Ottoline, Lawrence reassured her that his response to the soldiers ‘isn’t my disordered imagination’ (2L 331). The statement reveals his awareness of how others might interpret his reaction. Lawrence responded to his anguish over the war by developing a theory which contained and made sense of it; he interpreted everything through the theory, making the troubling outside world over into his own imaginative universe and ordering it in his writing. This made him an impatient, intolerant and sometimes insensitive friend and contact. When Barbara Low visited for Easter, Lawrence found her irritating precisely because she persistently questioned his responses and attitudes.29 On hearing that Maria Nys, a Belgian refugee living with Ottoline (and the future wife of Aldous Huxley), had attempted suicide at a moment of crisis, perhaps fearing being sent away by her patron, Lawrence told Ottoline that she was responsible for it: he detected wickedness in her attitude and an underlying desire to torture Maria.30 Ottoline was understandably cross on reading his ‘elaborate theory’ (2L 329).

Lawrence’s reading was also affected by his philosophising. When he read a volume of Van Gogh’s correspondence in late February, he felt that the artist’s madness proceeded from the denial of his desire for ‘a united impulse of all men in the fulfilment of one idea.’ Lawrence told Ottoline that Van Gogh ‘struggled to add one more term to the disorderly accumulation of knowledge’ instead of pulling it down altogether: in doing so, he was ‘submitting himself to a process of reduction’ (2L 296–7). After reading Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot (1869) in March, Lawrence detected in the author a desire to profess love while feeling evil hatred.31 His interpretations are closely shaped (and perhaps even bounded) by his developing philosophy.

The darkness of Lawrence’s mood was soon made worse by his financial worries. He was pursued by solicitors for divorce costs which he was unable to pay. He had to attend the Probate Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court on 10 May to declare current funds and future income; he avoided being declared bankrupt, but by the end of the month he still feared that submission of The Rainbow to Methuen might result in a petition to the publisher for payment of outstanding monies. Only Robert Garnett was able to set his mind at rest on this issue;32 the situation required some careful manoeuvring with Pinker to secure payment for the novel without confiscation. The sinking of the RMS Lusitania on 7 May had deepened anti-German feeling and produced riots in London a few days later, so that Frieda’s longing for her children was exacerbated by her isolation as a German woman in war-time England. She and Lawrence tried hard to find her a room in Hampstead, which would allow her to be alone, and at least to see the children on their walks to and from school, but they were late in applying for one property; only in early June did they settle on a flat at 1 Byron Villas, Vale of Health, ‘right on Hampstead Heath,’ for ‘£36 a year’ (2L 354). They would move there in August.

Lawrence was, however, ultimately unsympathetic to Frieda’s plight. He told Kot: ‘She spends her time thinking herself a wronged, injured and aggrieved person, because of the children, and because she is a German. I am angry and bored’ (2L 343). A stay in London from 7 to 10 May, and a subsequent two-day visit to Cynthia Asquith in Brighton, had proved difficult. Lawrence found the capital ‘like some hoary massive underworld, a hoary, ponderous inferno’ (2L 339); at Brighton, he had felt an urge to walk over the edge of a cliff.33 Cynthia Asquith described the company of her guests as ‘intoxicating’; in her diary, she referred to Lawrence as an ‘X-ray psychologist’, able to give ‘the most subtly true analyses of people.’34 After he had left, she asked him to provide an analysis of her son, John, an undiagnosed autistic child. Lawrence responded with a good deal of agitation at her ‘demand for a letter’, feeling that she was treating him as ‘a mixture between a professor of psychology and a clairvoyant, a charlatan expert in psychiatry’ (2L 335).

(v) ‘England, My England’

Into this situation came Monica Saleeby, Viola’s eldest sister, who had suffered a nervous breakdown following the break-up of her marriage; she came to live on the Meynell estate with her 10-year-old daughter, Mary. The young Mary had received no formal education, so Lawrence agreed to give her regular morning tuition in preparation for her starting at St Paul’s Girls’ School in September. It was one of the few things which bound him to Greatham as the summer drew on. Lawrence explained to Ottoline that Monica ‘just flops in bed for 3 weeks’ (2L 344). She had a nurse and doctor to care for her, and was driven out to various places to help her convalesce. Lawrence joined her for one trip to Bognor. Here, he saw a soldier with an amputated leg on the pier, and noted how he was the object of female attention: ‘he is strangely roused by the women, who seem to have a craving for him’ (2L 342). This was another incident which found its way into ‘The Crown’: it provided further evidence of the widespread fascination with fighting and deathliness.35

Lawrence’s sense of bitterness at the authorities deepened in the wake of his dealings with Weekley’s solicitor: he now saw himself as ‘an outlaw’ and a ‘secret enemy, working to split up and dismember the pack from inside’ (2L 352). A sharp and satirical short story he wrote on Amy Lowell’s typewriter at the beginning of June encapsulates his spirit of resistance to patriotism and propaganda. In the first version of ‘England, My England’ (published in the English Review in October), Lawrence built on what he knew of the lives of the middle Meynell daughter, Madeline, her soldier-husband Perceval Lucas, and their three daughters, to explore the links between marital dissatisfaction and the compensatory attraction to grotesque self-realisation through death at the Front. The central character in the story, Evelyn Daughtry, is an ineffectual husband and father thoroughly alienated from his wife Winifred and their children, and interested only in gardening. One of his daughters is accidentally maimed by a ‘sharp old iron’ (EmyE 222) left lying around in their garden; Evelyn has to defer to Winifred’s father to secure the services of a specialist doctor for her. Only the outbreak of war causes Evelyn to gain a sense of purpose and motivation. He enlists in the army and is stationed at Chichester before being drafted into the artillery and shipped out to France. Here he feels fulfilled and satisfied as an agent of death: ‘a destructive spirit entering into destruction’ (EmyE 225). In the shocking finale, he is maimed by an exploding shell while manning his gun, but still manages to shoot three Germans before being shot and stabbed to death. His face is mutilated by a German soldier who is compelled to remove any trace of Evelyn’s ‘ghoulish, slight smile’ (EmyE 232).

Lawrence’s title – ‘England, My England’ – subverts W. E. Henley’s patriotic jingoism,36 while the battlefield descriptions cast a bitter and ironic light on the tales of heroism and selflessness circulating on the Home Front. The Meynell family would feel terribly hurt by the story. Lawrence lighted on small details (like Percy Lucas’ love of his garden, and the tragic accident which befell their daughter Sylvia in summer 1913) and presented them as symptomatic and foreboding. This is characteristic of Lawrence’s tendency in the early war period to extrapolate and schematise, seeing small details and incidents in terms of larger unconscious motivations. When Percy Lucas was killed in France a year later, on 6 July 1916, Lawrence regretted that he had published the story.37 He did not flinch, however, from upsetting friends and even injured soldiers (like Beb Asquith, Cynthia Asquith’s husband, who returned hurt from action in Flanders in early summer 1915), telling them that a lack of emotional fulfilment and the power of innate violence lay behind the call to arms, rather than any grander or more noble objectives.38

Lawrence continued to encourage friends to join with him in his resistance to the war. Parts of his philosophy were sent to Forster, Russell and Ottoline. When Lawrence heard that Trinity College had rescinded its decision to appoint Russell to a Research Fellowship, instead renewing his lectureship for five years (perhaps owing to his involvement with the Union of Democratic Control), he encouraged Russell to be glad and to embrace separation.39 Russell travelled alone to stay with Lawrence at Greatham from 19 to 20 June. During these days he and Lawrence developed a plan to deliver a series of anti-war lectures in London in the autumn: Russell would lecture on ‘Ethics’, Lawrence on ‘Immortality’ (2L 359). The day after Russell left, Cynthia and Beb Asquith motored the Lawrences out to see them in Littlehampton. Lawrence had a ‘war talk’ with Beb on the beach, insisting that the conflict was caused by a ‘will to destroy’ in each of the soldiers; Beb’s counter-arguments fell on deaf ears.40 A recent visit to Garsington had convinced Lawrence that this would be a fitting place to host revolutionary discussions.41

Lawrence began revising proofs of The Rainbow in early July; at the same time he responded to Pinker’s call for changes to objectionable phrases. His revisions were so extensive that Methuen would exercise their contractual right to charge him for exceeding the stated printer’s fees.42 The novel’s concluding vision of an old life swept away and a new one issuing forth must now have seemed increasingly alien to Lawrence as the desperate optimism he had felt in the first months of the war receded. He was preparing to leave Greatham: this time the departure would signify not a re-birth, but a determination to leave behind the cloister in order to fight against the world he hated.43 Lawrence visited London from 10 to 12 July, staying in Hampstead with Dollie Radford (the poet and playwright whom he had first spoken to at length in March when she stayed on the Meynell estate).44 Dollie helped Lawrence and Frieda to plan for their move, offering them accommodation while they decorated and prepared the flat.

Fundamental differences between Lawrence’s and Russell’s approaches to the war soon emerged. Russell sent Lawrence a draft of ‘Philosophy of Social Reconstruction’: an outline of the lectures he planned to deliver in London. Lawrence obliterated it with negative comments. He thought that Russell was too concerned with social criticism rather than with reconstruction; he told him to avoid the popular approach and give serious attention to the relationship between the individual and the state. Lawrence’s own philosophy was being re-conceived through the lens of John Burnet’s Early Greek Philosophy (1892).45 His letters to Russell, Ottoline and Cynthia Asquith during July show the extent to which his politics had been altered by his despair and hatred of society. He felt that the state was collapsing and that the war would ‘develop into the last great war between labour and capital.’ If labour won, then Britain would be plunged into ‘another French Revolution.’ Lawrence believed that the solution was to dispense with notions of equality and embrace a new state model in which ‘every man shall vote according to his understanding’ (2L 366). This effectively meant that ‘the artizan’ would vote for the things that immediately concerned him, but ‘electors for the highest places should be the governors of the bigger districts’ (2L 368). There would be a Dictator and Dictatrix to control the public and private lives respectively. Both Ottoline and Russell expressed concern at Lawrence’s ideas and language. In response to Russell’s objections, Lawrence insisted: ‘It isn’t bosh, but rational sense.’ He now envisaged the Dictator as ‘an elected King, something like Julius Caesar’ (2L 371).

Lawrence rightly worried that he and Russell might not share a unanimity of purpose. He admitted to shrinking from the idea of delivering the lectures, longing for the safety and remoteness of his former writing life in Italy. The sense of vocation he had discovered in Italy to write in order to change his readership had given way to an imaginative concern with creating an alternative community, which had in turn been transformed into a plan for political action and revolution. It is easy to see how the tumultuous events of the past year led Lawrence down that path; it takes a particularly close and sympathetic reading of the letters to recover confusion and naivety from the constant repetition of reactionary bitterness.

(vi) Hopefulness – and despair

Lawrence left Greatham on 30 July to spend four days in Littlehampton, going on excursions with Dollie Radford and her daughter Margaret, before travelling on to London and the new flat. Shortly before his departure he informed Pinker that Duckworth had expressed interest in ‘a book of my sketches’ (2L 372): these were the travel pieces he had written during 1912 and 1913, to which he had long intended to add further essays on Gargnano, San Gaudenzio and Fiascherino. He sent Pinker an essay entitled ‘The Crucifix Across the Mountains’ (a completely re-written version of ‘Christs in the Tyrol’) and from 20 August started forwarding revised versions of the other essays to Douglas Clayton. He sent all the typed essays to Pinker, together with a new piece entitled ‘San Gaudenzio’ (written by 11 September), on 20 September, promising to write more sketches in order to bring the volume from 30,000 up to 50,000 words.46

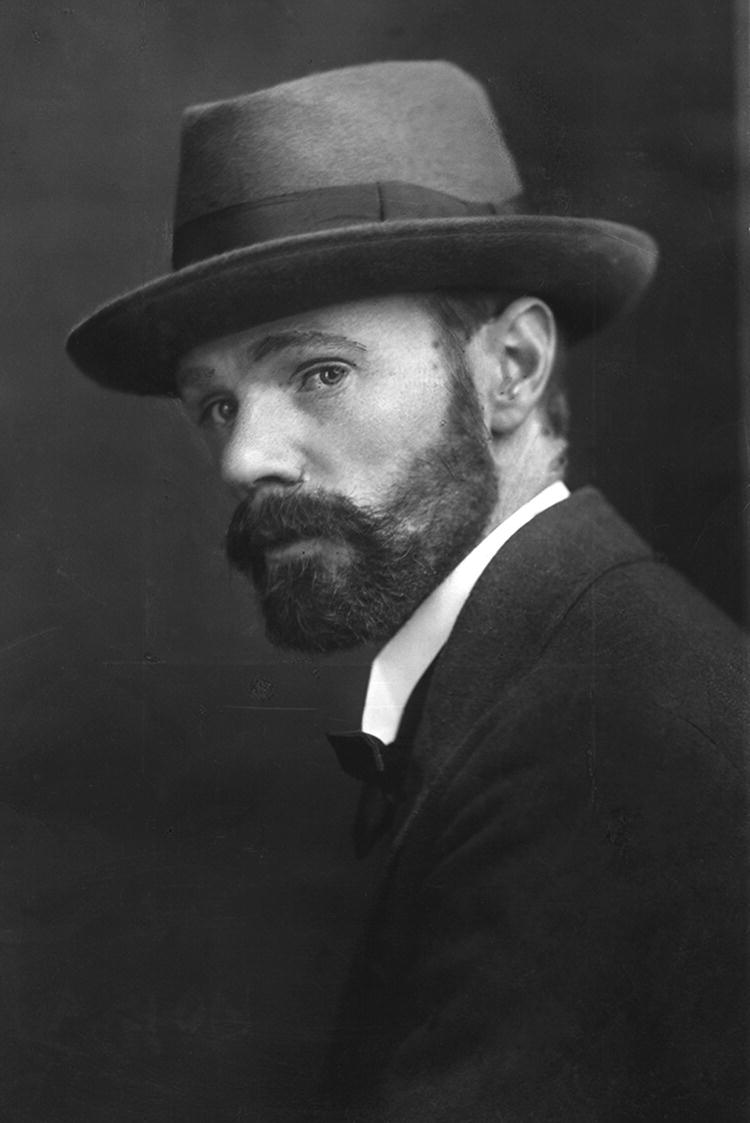

The first weeks in Hampstead, in early August, were spent furnishing the new home. On 6 August, Frieda was surprised to receive a letter from Weekley’s solicitor stating that she could see her children for 30 minutes in his office on 11 August (her thirty-sixth birthday). Weekley had learnt that she had moved to London and realised that she would go on shadowing the children on their way into and out of school; she was thrilled at being allowed to see them, though their cool response to her revealed how much of a stranger she had become during the past three years. At some point in the late summer, Lawrence had his photograph taken by the London firm of Elliott and Fry. Two of the surviving studio shots show him in formal poses: in one he is seated at a desk pretending to read a book; in the other he is wearing a trilby hat. The photographs were probably intended to help publicise The Rainbow; they show Lawrence as a professional author at the very moment when he seemed poised to consolidate his reputation on the London literary scene.

Figure 7 D. H. Lawrence, London, late summer 1915.

(© National Portrait Gallery, London.)

The sleek publicity images of the suited and upwardly mobile author contrast sharply with the reality of Lawrence’s embattled relationship to the English state and desire to speak out against the war. In Littlehampton he had quarrelled with Dollie about ‘the Infinite’: he may have been thinking about the topic of his planned lectures with Russell. By mid-August, however, these seemed remoter than ever. He told Cynthia Asquith: ‘I don’t know if they will ever begin.’ Russell had told Lawrence that he cherished illusions and could not think.47 Lawrence responded by asserting that Russell’s concern for ‘democratic control and the educating of the artizan’ was pure bad faith: ‘all this, all this goodness, is just a warm and cosy cloak for a bad spirit.’ If Russell was not going to fall in with Lawrence’s ideas, then he must be just another ‘little established ego’ (2L 378) labouring within the old system and given up to the universal disintegration. Lawrence’s idea of gathering together ‘a nucleus of living people’ (2L 381) was swiftly disappearing in mutual misunderstanding and recrimination. Russell and Ottoline were dismissed as ‘traitors’ (2L 380).

At the beginning of September, just as the Zeppelin bombing raids began over London and the eastern counties,48 Lawrence, Murry and Katherine Mansfield lighted on the idea of ‘issuing a little paper, fortnightly, to private subscribers’ (2L 385). It would be entitled The Signature; it would be printed in the East End and circulated to the sympathetic few. Its main purpose would be to publish Lawrence’s ‘philosophy’ in serial form, though Murry would contribute writings on ‘freedom for the individual soul,’ and Katherine some ‘little satirical sketches’ (2L 386). The plan was also to have an associated ‘club’ of contributors and readers; a room for its meetings was hired at 12 Fisher Street, Southampton Row.49 Leaflets were produced in order to secure private subscriptions. Lawrence sought support from (among others) Russell and Ottoline, Forster, Ernest Collings, Willie Hopkin (who was asked to drum up support in Sheffield, and to contact Alice Dax, Blanche Jennings and Jessie Chambers),50 Arthur McLeod and Cynthia Asquith, plus Harriet Monroe, Amy Lowell and Zöe Akins in America. By 22 September they had only heard back from around 30 subscribers; by 2 October this had risen to just 56.

Russell refused to subscribe to The Signature. He did, however, send on an essay entitled ‘The Danger to Civilisation’ for publication in it. Lawrence, doubtless irritated by Russell’s refusal to offer financial support for the venture, hated the piece. On 14 September he replied ‘very violently’ (2L 393), telling Russell that the pacifist sentiments he expressed in his essay were ‘a plausible lie’ intended to hide the violent nature of his unconscious desires: ‘What you want is to jab and strike, like the soldier with the bayonet, only you are sublimated into words.’ The letter ended by accusing him of ‘perverted, mental blood-lust’; Lawrence suggested that they should ‘become strangers again’ (2L 392). It was a brutal letter, full of hatred for what Lawrence saw as Russell’s hypocrisy and intransigence. Russell took its accusations seriously enough to consider committing suicide. Once the mood passed, however, he dismissed Lawrence’s letter completely; after a brief rapprochement in mid-November, he would come to despise Lawrence.51

October began with great hope, but ended in despair. The Rainbow was published by Methuen on 30 September. Lawrence detested the popular dust-jacket Methuen had put on it, and the changes he made in the copy he gave to his sister Ada show that he would have wished to revise it further,52 but he had every reason to feel proud of his achievement. He was keen to hear from Pinker ‘how the libraries and so on behave,’ but felt that if Methuen did not make money from it in the short term, then ‘he will do so later’ (2L 406). By 2 October he had finished all six of his ‘Crown’ essays for The Signature and felt that they were ‘very beautiful and very good.’ He was convinced that ‘if only people, decent people, would read them, somehow a new era might set in’ (2L 405). Pinker had also negotiated an agreeable contract with Duckworth for the book of Italian sketches.53 Lawrence would work on the second half of the book in the coming weeks, writing four wholly new essays: ‘Il Duro’, ‘Italians in Exile’, ‘On the Road’ (later re-titled ‘The Return Journey’) and ‘John’. The complete typescript was sent to Duckworth on 26 October.54

Lawrence’s optimism, however, was soon dashed. The Signature attracted less than half of the subscriptions it needed in order to survive, and only three of the six planned numbers appeared (on 4 and 18 October, and 1 November). Even sympathetic readers like Cynthia Asquith responded in a hostile spirit to Lawrence’s philosophy, disturbed by its ‘comfortlessness with regard to the war’ (2L 412). She found The Rainbow ‘strange, bewildering, disturbing’; she thought that the intensity of the anti-war sentiments expressed in ‘The Crown’ might ‘technically … amount to treason.’55 The two meetings at Fisher Street, on 11 and 24 October, were a disappointment (the second one only going ahead because there was insufficient time to cancel it); the tenancy agreement lapsed at the end of the month and was not renewed. The death of Katherine Mansfield’s brother on 6 October and Cynthia Asquith’s brother on 19 October came as a real blow, too, as did news of the death of Else Jaffe’s eight-year-old son Peter.56

Lawrence’s unhappiness with England caused him to think of going to America with Frieda and Murry. He applied for passports and asked Cynthia to write to a friend in the Foreign Office with a view to expediting matters. Even when he was advised against wintering in New York on medical grounds, he clung to the idea of getting away to the north of Spain.57 His despair about the war and his desire for a new world, and a new life, away from England’s debilitating atmosphere, are made clear in the poem ‘Resurrection’, which he sent to Harriet Monroe on 26 October, and the short story ‘The Thimble’, completed by 30 October. He would quote six lines of the poem in a letter to Cynthia Asquith on 28 November: ‘Now like a crocus in the autumn time / My soul comes naked from the falling night / Of death, a cyclamen, a crocus flower / Of windy autumn when the winds all sweep / The hosts away to death, where heap on heap / The leaves are smouldering in a funeral wind’ (2L 455).

Lawrence remained oblivious for some time to the fate of The Rainbow. The libraries had refused to stock it, and Doran in America told Pinker that it would be impossible to publish it there without significant revisions.58 Worse still, reviews were damning. Robert Lynd in the Daily News on 5 October condemned it as ‘largely a monotonous wilderness of phallicism,’ James Douglas in the Star on 22 October described it as ‘utterly lacking in verbal reticence’ and opined that it had ‘no right to exist in the wind of war,’ while Clement Shorter in the Sphere stated that there was ‘no form of viciousness, of suggestiveness, that is not reflected in these pages.’59 Catherine Carswell, who was ‘puzzled and disappointed’ by the novel, wrote a positive but not uncritical review of it in the Glasgow Herald of 4 November, and lost her job as a result.60 The novel’s negative reception alerted the authorities, who sought to prosecute Methuen under the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, visiting the publisher’s offices on two occasions (the second time on 5 November with a Bow Street magistrate’s warrant to remove all unsold copies and unbound sheets). Methuen recalled copies from shops. The company did not resist the process: in fact, it had discreetly withdrawn advertisements for the novel on 28 October and was inclined to bring matters to a speedy conclusion. A hearing before a magistrate was planned for 13 November.

(vii) ‘The end of my writing for England’

Lawrence first heard about the magistrate’s warrant and the suppression of sales on 5 November through W. L. George and then Pinker. It made him feel ‘sick, in body and soul.’ On the same day his and Frieda’s passports arrived. He was now determined to go to Florida for the winter. America seemed to offer the only chance for him as a writer. He told Pinker: ‘It is the end of my writing for England’ (2L 429). He spent that evening with several friends (including Kot, Murry and Katherine Mansfield) at the studio of the Honorable Dorothy Brett (a member of the Bloomsbury circle whom he had met through Mark Gertler); the party was gate-crashed by a large group including Lytton Strachey and Clive Bell.61 The drunkenness that ensued was certainly out of keeping with Lawrence’s mood; Brett was unaware of the dreadful news that Lawrence had just received. The next day he heard from Pinker that Doran had arranged for Benjamin W. Huebsch in New York to publish The Rainbow; he agreed to let Huebsch proceed with publication on the condition that he was made fully aware of recent events. Lawrence soon began to seek financial support from contacts like Edward Marsh and Ottoline Morrell for his plans to settle in America; Marsh gave him £20 and Ottoline gathered together £30 from a group of friends (including Russell). A visit to Garsington between 8 and 10 November lifted Lawrence’s mood somewhat, though the beauty of the house and grounds offered him ‘a sort of last vision of England … the beauty of England, the wonder of this terrible autumn’ (2L 434).

Methuen pleaded guilty to the charges of publishing obscene material at the hearing on 13 November; Lawrence was not given the opportunity to defend his work. In his summing up, the magistrate, Sir John Dickinson, called the novel ‘utter filth’: he ‘made an order for the copies of the book in the possession of the police to be destroyed’ and forced Methuen to pay costs of £10 10s.62 Lawrence subsequently took various routes to try to reverse the court’s decision. He wrote to G. Herbert Thring, Secretary of the Society of Authors, asking whether the committee might consider the issue of the suppression of his novel.63 He sought support for The Rainbow from fellow authors: George Bernard Shaw sent him £5, and the poet John Drinkwater was anxious to help out, too.64 Arnold Bennett praised the novel, referring to it as ‘beautiful and maligned’ in an article in the Daily News on 15 December.65 Prince Antoine Bibesco, a Romanian diplomat married to the step-sister of Beb Asquith, offered to get the novel published with Editions Conard in Paris.66 Lawrence also approached Ottoline’s husband, Philip, a Liberal MP, with a view to raising questions about the proceedings in the House of Commons. Morrell duly did so on 18 November, and submitted a further question on 1 December. The Home Secretary, Sir John Simon, confirmed that action was taken against the publisher, not the author, so it was Methuen’s decision whether or not to call the author to defend himself against the charge; Lawrence would have needed to insert a clause in his contract if he wanted to compel the publisher to inform him of any legal proceedings brought against his work.67

Lawrence alternated between hopelessness and the desire to fight for a new audience. On 15 November he sent the manuscript of The Rainbow to Ottoline and told her to burn it if she did not want it: ‘I don’t want to see it any more’ (2L 435). On the other hand, meetings with the young poet Robert Nichols (who had been injured serving with the Royal Field Artillery) and Philip Heseltine, a 21-year-old composer and friend of Frederick Delius, made Lawrence look to the future. He supported Nichols’ verse and took Heseltine with him to Garsington from 29 November to 2 December. Heseltine, in turn, would write to Delius to enquire after accommodation for Lawrence in Florida. During December Lawrence gathered around him a nucleus of young people: Heseltine, an Indian named Hasan Shahid Suhrawardy, the Armenian-born writer Dikran Kouyoumdjian (who would later gain notoriety, and wealth, writing under his adopted name ‘Michael Arlen’), and Aldous Huxley. He felt that he could ‘unite’ with them to ‘do something’ (2L 468). He believed that Heseltine and Huxley might even follow him to Florida.68

The few days at Garsington brought home to Lawrence the precariousness of his current situation. He joined Ottoline and her friends in dressing up and acting out scenes, using her collection of ‘exquisite rags, heaps of coloured cloths and things, like an Eastern bazaar’ (2L 465). ‘Make-belief’ seemed like the only way to be truly happy. Walking around the grounds he saw turkeys in a nearby farmyard; they reminded him of the wild turkeys which he had been imagining in Florida, so that returning to the house was like moving between visions of the new world about to be born and the old one which he felt dying away. The long, visionary, rhapsodic note which he wrote for Ottoline on 1 December commemorated his feeling of psychological displacement, deathliness and resurgent hope.69

He was soon displaced in a very practical way, too, since he had decided to let the flat in Byron Villas from 20 December and sold the furniture. Prince Bibesco called to express his outrage at the treatment of The Rainbow, while Donald Carswell – a recently qualified barrister – urged Lawrence to take further legal measures.70 Lawrence was glad, though, to let things rest; although he joined with Pinker in organising the signing of a petition against the prosecution, his thoughts were now set on leaving England. When, in mid-December, he received a copy of Huebsch’s American edition of the novel, published on 30 November, he was ‘sad and angry’ (2L 480) to find it expurgated, but he took no further action. Lawrence did not know it at the time, but Huebsch (who decided to publish The Rainbow after receiving glowing reports on it from two trusted advisers)71 had only distributed a small number of copies and had not advertised it or sent out review copies. He was afraid that the Society for the Suppression of Vice would cause trouble if they found out about it.

The idea of escaping to Florida was a great consolation for Lawrence.72 However, he would not be allowed to leave the country without first gaining an exemption from military service.73 On 11 December he queued for nearly two hours at the recruiting station in Battersea Town Hall to be attested and get the exemption. He took along with him a certificate which Dr Ernest Jones, a friend of Barbara Low, had written for him to support his case,74 but in the event he came away before being seen, feeling the situation (and his impending rejection) to be ‘vile and false and degrading’ (2L 474).

This meant that after spending Christmas with his family at Ada’s home in Ripley, he would need to find somewhere to stay in England before going abroad. He considered Devon, Somerset and a farmhouse in Berkshire, before accepting the novelist J. D. Beresford’s offer to stay at his cottage in Cornwall. Murry had helped him to secure the offer, so on 20 December Lawrence wrote to Katherine Mansfield suggesting that, on her return from France, she and Murry should come to Cornwall and they should all ‘live together … in unanimity’ (2L 482). It was a gesture toward the idea of communal living which he had conceived the previous Christmas.

On 21 December, the Lawrences left Byron Villas. They stayed first with Vere Collins (of Oxford University Press); Collins showed Lawrence a book of Ajanta frescoes recently published by the Press, which Lawrence loved. He eventually bought a copy with Russell and sent it to Ottoline as a Christmas present. To Lawrence the frescoes represented ‘the zenith of a very lovely civilisation, the crest of a very perfect wave of human developement [sic]’ (2L 489). They would have reminded him of the ‘blood-being or blood-consciousness’ which had fascinated him when he read James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890–1915) and Totemism and Exogamy (1910) a few weeks before.75 On Christmas Eve he headed to Ripley with Frieda. Returning home and seeing all his family (even Emily, who was down from Glasgow) was ‘very queer.’ He explained to Cynthia Asquith that he was ‘fond of my people, but they seem to belong to another life, not to my own life’ (2L 486). He loved to see his sisters’ children – Margaret (‘Peggy’) King and John (‘Jack’) Clarke – but he quarrelled violently with his brother George and felt that the local miners were so immersed in ‘wages and money and machinery’ (2L 489) that they could not see beyond such things. He was glad to leave for Cornwall on 29 December.