18

‘Dropping a Little Bomb in the World’s Crinoline of Hypocrisy’: May 1928–August 1929

(i) Polemical essays

While Lawrence was waiting for the paper to arrive in order to print his novel, he wrote a short ‘Note’ and an alternative, longer ‘Foreword’ for his Collected Poems, since Robert Bridges had not responded to Secker’s request for an introduction. He also set his mind to writing a short article for the Evening News, in response to an approach from its literary editor. The piece, entitled ‘The Bogey Between the Generations’, reflected on the hypocrisy of an older generation of men and women who claimed to censor works of art in order to protect younger female readers, when in fact those younger women were much more open-minded and receptive. This article was published on 8 May under the title ‘When She Asks “Why?” ’ (later re-titled ‘The “Jeune Fille” Wants to Know’); it was well received by the editor and the readership, and its success led to Lawrence becoming a regular contributor to the newspaper.

Lawrence quickly became adept at writing stimulating and polemical articles on topical issues around censorship, relations between the sexes, and modern living. Producing a ‘four-pager’ (6L 401) was relatively effortless, and he could demand upwards of 10 guineas for 1000 words of text. His next contribution to a paper would be written as part of a series by men in the Daily Chronicle on the subject of ‘What Women Have Taught Me’. Lawrence’s article was entitled ‘That Women Know Best’. Taking his mother’s dominance in the Lawrence household as his example, he argued that women’s downright belief in moral absolutes had taught him ‘not to be too sure of right and wrong’ (LEA 85). The article was accepted around 15 June, but not published until 29 November. On 13 May, Lawrence sent Nancy Pearn the manuscript of ‘Laura Philippine’, which he had written over a year earlier; she managed to place this account of the hedonism of the younger generation in T.P.’s and Cassell’s Weekly (where it was published on 7 July).

During May, Lawrence saw Enid Hilton and her husband, who stayed for a time close by in Vingone during their holiday in Italy. He asked Enid to take back to London seven of his watercolours and three smaller oil paintings; he was preparing to exhibit his work back in England. He began to think that some of Earl Brewster’s paintings might be exhibited alongside his own, and he wrote to Mark Gertler asking advice on the best way to transport the remaining paintings, and how best to photograph them.1

Only on 31 May did he receive the last of the proofs of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. It was at this time that Lawrence – suffering from flu – developed the habit of writing in bed. At some point in late May he produced a short article entitled ‘All There’. It was written in the form of a conversation between a young couple and the narrator, dealing with the man’s inability to compete with jazz for his sweetheart’s attention. Lawrence may have hoped that it would appeal to a magazine like T.P.’s and Cassell’s Weekly, which had accepted ‘Laura Philippine’, but Nancy Pearn was unable to place it. He also wrote the short story ‘Mother and Daughter’, about a domineering mother (Rachel Bodoin) and the negative influence she has over her daughter (Virginia); the daughter is only saved by the timely intervention of an older Armenian suitor (perhaps based on Michael Arlen) whose forthrightness and imperviousness to Rachel’s spite prevent him from being summarily dismissed in the fashion of an earlier romantic interest. The mother’s final taunt as Virginia prepares to leave for Paris with her new husband is shocking: she refers to her daughter as ‘just the harem type.’ The daughter’s insouciant response emphasises the difference between the generations: ‘I suppose I am! Rather fun! … But I wonder where I got it?—Not from you, mother—’ (VG 122).

(ii) Travelling with the Brewsters

On 7 June, Lawrence sent back to Orioli the corrected proofs of his novel, together with the 1000 signed and numbered sheets which would face the title-page.2 The day before, the Brewsters had come to visit; they were staying in Florence, since Lawrence had told them that they could use the Villa Mirenda once he and Frieda had left. Lawrence looked so ill that they decided on the spur of the moment to accompany him and Frieda on their travels in order to spend time with their friend while they still could. On 10 June, they all left Florence together. Lawrence had no clear plans, but he was eager to improve his health by heading to the French or Swiss Alps and staying somewhere with an altitude similar to Les Diablerets, which he felt had been so good for him in January. On the first stage of their journey (a train trip to Turin, where they stayed overnight) Lawrence treated the Brewsters to a disturbingly passionate rendition of the Moody and Sankey hymns he knew so well, including the temperance song ‘Throw Out the Life-Line’, which he illustrated with appropriate arm gestures, dragging in imaginary drunkards with grotesque delight.3 He knew every word of every hymn, and his skills as a mimic were put to good effect in mocking the earnestness of the salvationists, exposing the manic aggression which he sensed lay beneath their expressions of benevolence.

From Turin, the group travelled to Chambéry, Aix-les Bains and Grenoble in the Rhône-Alpes region of south-eastern France. They stayed here from 11 to 13 June. Lawrence liked it, but the heat was oppressive, so on 14 June they headed up into the mountains. They checked into the inauspicious-sounding ‘Hotel des Touristes’ in St Nizier-de-Pariset. The hotel was situated in a pleasant spot and at 3500 feet the air was much fresher. However, Lawrence struggled to adjust to the thinner air and his coughing during the night was so severe that the manager spoke with Earl Brewster in the morning and asked them to leave.4 Brewster told Frieda, and they persuaded Lawrence to move on, remaining silent about the reason for their sudden departure; when he found out, he ‘felt very mad’ (6L 428). Luckily, by that time they were settled at the Grand Hotel at Chexbres-sur-Vevey in the Swiss canton of Vaud, where the Brewsters had stayed once before. It was ‘a biggish hotel, but decently comfortable’ (6L 426), with wonderful views out over Lake Geneva.

They stayed for three weeks. On 19 June, two days after their arrival, Frieda left to spend a few days with her mother in Baden-Baden (she would return on 25 June). In her absence, the Brewsters offered Lawrence invaluable support and company; they looked after him, and in turn he shared with them the things he was writing, asking their opinions and seeking their advice.5 Although Lawrence told Arthur Wilkinson that he was ‘feeding and loafing’ (6L 433) during this period, in reality he was keeping a close eye on his literary affairs. On one occasion he spoke vehemently about money, telling the Brewsters: ‘One must fight for his just share, never mind if peace of heart were dearer than the just share!’6 He was now anxious to hear from Orioli about progress with the binding of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and plans for its distribution.7 Secker’s edition of The Woman Who Rode Away had been published on 24 May, followed the next day by Knopf’s; Lawrence was aware of the negative reviews that the book was receiving in America, but he acknowledged the ‘boost’ it got from Arnold Bennett’s positive notice in the Evening Standard.8

Once settled in the hotel, he began writing the second half of The Escaped Cock, made arrangements to send his paintings to London (though he did not decide for sure to exhibit at Dorothy Warren’s gallery until 4 July),9 and at the same time worked on a number of newspaper articles ‘to keep the pot boiling’ (6L 469). In one of the pieces, entitled ‘Thinking About Oneself’, Lawrence criticises the modern obsession with ‘forgetting oneself’ (LEA 91) through mass participation in immersive forms of entertainment like dancing to jazz or attending the cinema; he celebrates the fun involved in thinking through one’s complaints against life and questioning the meaning of happiness and fulfilment. The value of self-reflection for Lawrence consisted in getting outside one’s habitual perspective and viewing one’s actions and desires truthfully and earnestly in order to bring about some change in life. He was alert to the dangers of self-absorption and had a life-long aversion to self-advertisement. On 21 June he received a request to write a short autobiographical sketch for the Paris publishing house Kra, and tried to get Else Jaffe to send the one which she had written earlier for the Frankfurter Zeitung.10 He told Else: ‘I simply can’t write biographies of myself’ (6L 430). In the event, he was forced to write one,11 but the incident was telling: Lawrence was more inclined to explore his own desires, convictions and experiences through the shifting and relativising lenses of essays, poetry and fiction.

Other articles would be written in response to specific requests from the Evening News. ‘Insouciance’ drew on an experience Lawrence had with two elderly English ladies in a neighbouring room at the hotel, one of whom wished to engage him in a discussion about international politics across their balconies while he was trying to appreciate the beauty of the view; he used this incident to illustrate a modern tendency to worry about abstractions rather than responding to the physical world. ‘Master in his Own House’ and ‘Matriarchy’ contain wry reflections on contemporary gender roles of a kind guaranteed to appeal to a popular readership; they were happily accepted by the paper. A fourth article, entitled ‘Ownership’, expressing Lawrence’s resistance to the British obsession with property, was rejected.

Lawrence finally received his own copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the post on 28 June.12 The first copies were sent out to American subscribers, but the far more numerous British orders followed soon after. He was very anxious to make sure that the books arrived safely: he asked trusted friends to send him telegrams back with the single word ‘Received’. Most of the early copies seemed to move through the post with no problems, though Harold Mason in the States would advise him that his own copy had been confiscated by the authorities. More seriously, at the end of July he found that booksellers and bookdealers (like Foyles and B. F. Stevens and Brown Ltd) wanted to return copies once they discovered the nature of their contents. Lawrence had to arrange for friends in London (Enid Hilton and Kot) to pick them up and store them.13

(iii) Gsteig-bei-Gstaad

On 6 July, while all this drama was being played out, the Lawrences and Brewsters decided to move on, travelling to Gsteig-bei-Gstaad in the Swiss canton of Bern. They checked into the Hotel National, but three days later Lawrence found a little peasant chalet a mile higher up, at an altitude of around 4000 feet, in the village of Kesselmatte. It was located just below the snow-line on the Pillon Pass, around eight miles from Les Diablerets; members of the peasant family who owned it had moved further up the mountain for the summer and were glad to rent it out (the landlady and her daughter came daily, in the early evening, to help with the housework and to prepare a meal). There were a table and bench under a pear tree at the front of the chalet, where Lawrence could write and paint (he immediately began a watercolour study of men catching horses). The Brewsters stayed in the hotel, trekking up to see the Lawrences on most days, since Lawrence himself could not manage the uphill return journey.14 Brewster arranged for his Indian friend, Boshi Sen (a scientist working at the University of London) to give Lawrence ‘Hindu massages’ (6L 547); he and Achsah also listened to him reading his latest writings and encouraged him in his painting. A short time after arriving in Gsteig, Lawrence would paint ‘Accident in a Mine’ and ‘The Milk White Lady’ (based on lines from the folksong ‘The Two Magicians’, which he sang with the Brewsters).15

Between 11 and 17 July, Lawrence wrote a review of four books for Vogue, including Somerset Maugham’s short story collection Ashenden, or the British Agent (1928); he admired Maugham’s powers of observation, but found the characters flat and fake.16 He also wrote a short story entitled ‘The Blue Moccasins’ especially for Eve: The Lady’s Pictorial. Although it contains clear traces of its origin as a commissioned piece for a woman’s magazine, this story possesses a complexity in its characterisation and an open-endedness in its plot which lifts it above the level of mere domestic melodrama. It focuses on the experiences of a cultured and privileged middle-aged lady who marries a much younger bank clerk with whom she had become intimate before the war, only to find that their marriage is empty once he returns from active service as a captain in Gallipoli. The woman (named Lina McLeod) encourages her young husband to take up a job as a bank manager and resume his former interest in singing in the choir, but at the end of the story he has developed a new intimacy with a war widow of his own age who shares his popular tastes and predilections. Percy Barlow takes his wife’s prized blue moccasins and lends them to his new lover, who wears them in a Christmas Eve performance of a romantic play entitled The Shoes of Shagpat, in which they take the lead roles. Lina deigns to attend the performance at the last moment and confiscates her shoes from the stage in a fit of pique when she is forced to endure seeing her husband embrace Alice Howells. In the first version of the ending, she gives them the shoes back, but in the final version she refuses to return them. The story juxtaposes the older lady’s detachment and the man’s common touch in the community drama, with the shoes symbolising the fundamental differences in their outlook (since she wants to paint them in a still life, and he wants to use them in the play). We are left uncertain whether his latest intimacy is the real thing, or if he will return to his wealthy wife.

Cheques were now starting to come in for Lady Chatterley’s Lover; by 4 September Lawrence would have made around £700 from the novel. The experience of privately publishing it made him more assertive in fighting his corner with publishers and booksellers. When Martin Secker asked him to sign 100 special copies of his edition of Collected Poems, Lawrence insisted that he should receive one third of the extra money that would accrue from their sale. During August he would insist on receiving 25 guineas rather than 20 for signing 530 copies of Rawdon’s Roof for the limited edition planned by Elkin Mathews as part of its ‘Woburn Books’ series.17 Lawrence felt wealthy enough to offer to pay for his sister Emily to come out and join him in Switzerland;18 on 5 August he heard that Emily’s 19-year-old daughter, Margaret (‘Peggy’), would be accompanying her. He was certainly in need of cheery company, since the adjustment to the higher altitude initially worsened his cough and made him feel seriously ill: he told the Huxleys at the end of July that he had ‘made [a] design for my tombstone in Gsteig churchyard, with suitable inscription: “Departed this life, etc., etc. – He was fed up!” ’ (6L 483).

His mood was not improved by the news that more copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover were being returned by British dealers, and that American copies were being retained by vigilant customs officials. Lawrence asked Enid Hilton and Kot to collect the returned copies and to drop off or post new British orders from their supply. He sought the advice of Laurence Pollinger at Curtis Brown, who in turn managed to secure further subscriptions. Enid proved very helpful in distributing the book, but Kot was more anxious and passed on rumours to Lawrence that a warrant had been issued for the impounding of all copies in Britain, and that undercover police agents were masquerading as booksellers to catch them out.19 At the height of his concern, Lawrence arranged for 30 copies to be passed to Richard Aldington for safekeeping; Aldington, who had told Lawrence that the novel was ‘a feather in the cap of the XX century’ (6L 484), was happy to help out, but Lawrence later came to feel that the move had been unnecessary and was angry with Kot for over-reacting.

There was a strange contrast between the uneventful, ‘serene’ (6L 491) life in the chalet in Gsteig-bei-Gstaad and the daily upheaval of dealing with correspondence in relation to all the controversies in Britain and America. Lawrence did manage, however, to produce another oil painting during August, on a board given to him by Earl Brewster: ‘Contadini’ shows two nude Italian peasants (the figure in the foreground perhaps based on Pietro back at the Villa Mirenda).20 He also finished the second half of The Escaped Cock, and wrote two further articles for the Evening News (‘Why I Don’t Like Living in London’ and ‘Cocksure Women and Hen-sure Men’)21 as well as an essay entitled ‘Hymns in a Man’s Life’. In the latter, Lawrence reflected on his love for the mystery and wonder of certain hymns sung at the Congregational Chapel in Eastwood and at his school, which he much preferred to the ‘sentimental messes’ (LEA 133) also available.

His sister Emily duly arrived with Peggy for a two-week visit on the morning of 26 August. Unfortunately, despite his pleasure in seeing them again, their stay put Lawrence in an awkward position, since to avoid shocking them he had decided not to tell his sisters about the decision to privately publish his novel.22 This meant that while they were around the chalet he could not openly express anxiety or outrage over the latest developments. The Brewsters left for Geneva on 30 August, which would have contributed to Lawrence’s sense of isolation, and matters were made worse by the atrocious weather over the three days between 28 and 30 August.

Lawrence spent the precious time he had alone in re-reading Stendhal’s La Chartreuse de Parme (1839) and he produced a painting entitled ‘North Sea’, depicting naked male and female figures ‘on the sand at the sea’ (6L 543). He was now eager to leave Gsteig and head to somewhere warmer – and drier – before conditions began to affect his health (he thought of taking up an invitation to join Aldington and Arabella Yorke for the winter at the Vigie – or small fortress home – which they were renting on the island of Port Cros, in the south of France). The fortnight of enforced secrecy about the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover brought home to him the difference between his own values and beliefs and those of his elder sister, and made him long for the company of his friends. He told Enid Hilton: ‘though I am glad to see them [Emily and Peg], it worries me and depresses me rather. I am not really “our Bert”. Come to that, I never was’ (6L 535). His annoyance and depression over Emily’s conventional attitude to things would ultimately make him reluctant to return to England during the autumn. He thought instead of going straight to the south of France after visiting his mother-in-law in Baden-Baden; he preferred to let Frieda travel alone to England and report back to him on the exhibition of his paintings in London.

(iv) ‘Red Trousers’

Emily and Peggy left on 7 September. Lawrence’s relief was tempered by his growing irritation with the American customs officials, who were now systematically impounding copies of his novel. On 8 September, Lawrence told Brett that he had sold ‘about 600 or 650 in Europe’, while only 140 had been sent to America and he had ceased sending any more until he heard ‘how many have not arrived’ (6L 550). He was infuriated to hear from American subscribers who claimed not to have received their copies; he suspected that American booksellers were lying about non-receipt (since he heard that they were selling the copies bought for $10 at the hugely inflated price of $50). The combination of official disapproval of his work and profiteering at his expense was particularly distasteful to him: he grew ‘tired of America and the knock-kneed fright in face of bullying hypocrisy’ (6L 568), and he felt that the Americans were ‘unclean and ignominious. So absolutely unbrave’ (6L 576).

He tried to evade the attentions of the customs officials by arranging for a number of copies to be shipped over the Atlantic with false wrappers: the title he mockingly chose for it was ‘The Way of All Flesh / by / Samuel Butler’ (6L 561). He had earlier used the invented title ‘Joy Go With You – by Norman Kranzler’ (6L 525). To avoid being exploited by the booksellers, he agreed to let Orioli sell the last 200 copies of the expensive edition at four guineas in Europe and $21 in America. The reaction of the American authorities forced his hand in one respect, however: although Alfred Stieglitz was eager to exhibit Lawrence’s paintings in New York (and Lawrence had received supportive letters about Lady Chatterley’s Lover from both Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe),23 he could not now risk having his paintings confiscated in transit, so he decided to cancel these plans and let Dorothy Warren mount a longer exhibition during her preferred time in late October or November. Friends like Kot warned Lawrence that his paintings would be likely to attract controversy and trouble for both himself and the gallery, but Lawrence was committed to ‘dropping a little bomb in the world’s crinoline of hypocrisy’ (6L 552).

That mood of bravery and rebellion against the authorities and middle-class opinion is delightfully captured in an article entitled ‘Red Trousers’, which he sent to Nancy Pearn on 13 September, for submission to the Evening News. Here, Lawrence discusses the admirable energy of modern crusaders who fight for worthy causes like socialism, or the freedom of small nations, or votes for women, but he argues that the outcome of their crusades is less interesting than the means they use to achieve it. He proposes a new crusade on behalf of comic insouciance, in order to undermine ‘the serious mock-morality of the film and the wireless.’ Wearing bright clothes in central London, crusaders would be expressing a simple light-hearted joy in life, of a type experienced during ‘really great periods like the Renaissance.’ This is an observation which Lawrence had earlier ascribed to Oliver Mellors.24 In a move which reflects his recent response to Emily’s visit, he dismisses social utility and openly celebrates the courage to be individual ‘in the teeth of a dreary convention’ (LEA 138). The success of journalistic pieces like this one led the BBC to approach Curtis Brown to secure Lawrence’s services for radio broadcasts. It is intriguing to think of Lawrence addressing a BBC audience on a range of topical issues, but his depiction of radio as a disembodied medium promoting the mindless consumption of words in Lady Chatterley’s Lover provides a graphic sense of his opposition to ‘broadcasting’. His decision not to return to England gave him sufficient reason to turn down the BBC’s offer, but he told Nancy Pearn that, in any case, the very idea of it made his ‘blood run cold’ (6L 552).

Lawrence was finally able to leave Gsteig in mid-September. He invited the Brewsters to join him and Frieda in Baden-Baden. Frieda’s mother had taken rooms for everyone at the Hotel Löwen in Lichtenthal. To mark the occasion of Earl’s fiftieth birthday, they all rode out together in two horse-drawn landaus to see the Altes Schloss; they also took the funicular up to the summit of the Merkur, and there were daily concerts in the Kurgarten and regular visits to the Kurhaus, plus plenty of opportunities to dine out and engage in good conversation.25

(v) Port Cros

During their stay in Baden-Baden, Lawrence heard that Raul Mirenda had turned the Pini family out of their home in San Polo Mosciano. This contributed to his decision to leave the Villa Mirenda for good. Accordingly, it was decided that Frieda would travel to Florence to pack up their things before coming to join him in the south of France for the visit to the Vigie on Port Cros. Lawrence left Baden-Baden with the Brewsters on 1 October (the day before Frieda), travelling first to Strasbourg and then via Lyon to Toulon. Unfortunately, the young porter was late bringing their luggage from the Hotel Löwen, so they were forced to take an afternoon train and were delayed in Strasbourg. They went into a cinema to keep warm. It was showing Ben Hur, and Lawrence was so appalled by the artificiality of the emotions on show that he told the Brewsters he had to leave or he would be ‘violently sick.’26 They travelled onwards during the night. Lawrence arrived in Le Lavandou the following morning; Else Jaffe met him at the station, and he parted company with the Brewsters (who were going on to Nice). He spent the next few days with Else, Alfred Weber and the Huxleys (who stopped off to see him en route from Forte dei Marmi to their house in Suresnes, near Paris). On 3 October, they all took a boat from Hyères to Port Cros, so that Lawrence could look at the place before Aldington arrived. It was a 10-mile journey and took two hours. Lawrence liked Port Cros, but thought it rather isolated. There was no shop, so all supplies had to come from the mainland. There were just three postal deliveries per week, and to get to the Vigie one had to face ‘an hour’s stony walk uphill’ (6L 584).

Back on the mainland, Else, Alfred and the Huxleys left on 5 October, and Lawrence waited by himself for Frieda to return. On 8 October he received a telegram from Aldington to say that the Vigie was fine and that they were looking forward to his arrival. However, he only heard from Frieda on 10 October. She had decided to stay in San Remo on her way back, instead of stopping with the Brewsters in Nice (as Lawrence had planned). Lawrence’s anxiety at not hearing from her reflected his tacit understanding that she was with Ravagli; Frieda was never a very reliable correspondent, but her silence during these days would have been deafening. She finally arrived on the evening of 12 October, having endured a three-hour taxi ride from St Raphael on account of a rail strike.27 They spent a few days together and travelled to Port Cros on 15 October.

On his arrival at the Vigie, Lawrence found that it was not the castle he had expected, but ‘a fortification on the top of the tallest hill of the island, a thick low wall going round enclosing a couple of acres of the hill-top’; inside, there was ‘a sitting room and four bed-rooms on the south side, a big dining hall, and kitchen, pantry’ (6L 592), plus a room they used for dining. It came with the services of a 28-year-old Sicilian named Giuseppe Barezzi, who cleaned the place and went with his donkey Jasper to collect supplies from the port. Aldington and Arabella Yorke were there with Brigit Patmore, an old friend of the Lawrences. Aldington and Brigit were busy writing during their time on the island: he was working on a translation of The Decameron and beginning Death of a Hero, while she was finishing off her second novel, entitled No Tomorrow. On sunny days the whole group would go down to the beach, but the nearest bathing spot was a 45-minute walk away and the steep road back prevented Lawrence from joining them.

Lawrence’s poor health and the location of the Vigie meant that he was just as isolated on Port Cros as he had been in the chalet in Kesselmatte. Frieda had returned from Italy with a bad cold, which Lawrence soon caught. He was confined to bed and had a few days of small haemorrhages. The weather on the mainland had been very settled and sunny, but it was more changeable on the island: Lawrence noted that they had ‘all weathers, from violent mistral to creeping hot fog’ (6L 596). He feared that the moist air was bad for his health. There were other reasons for his unhappiness on the island, too. At some point early in their stay, Aldington told Arabella that he intended to leave her; he began an affair with Brigit. The emotional fallout from this was painful: Arabella sought ‘consolation’ with the young Sicilian helper, and threatened (and maybe even attempted) suicide.28 Lawrence’s sympathy for Arabella caused him at one point to suggest to Brigit that she should leave the island with him and Frieda and let Aldington and Arabella sort themselves out.29 Lawrence’s disgust at Aldington’s treatment of Arabella would have been deepened by an event which revealed his (Aldington’s) willingness to encourage Frieda’s relationship with Ravagli. Aldington helped Frieda to keep up communications with Ravagli in Italy by collecting letters for her from the post office. After Lawrence’s death, Frieda would confide to her friend Martha Crotch that on one occasion a letter which Aldington fetched for her, addressed from Ravagli to Frieda, fell out of his pocket when he went to bathe, and Lawrence read it.30

Lawrence’s reaction to this confirmation of the powerful feelings which now bound Frieda to Ravagli is made clear in an exchange he had with Brigit, who was particularly attentive to him (the two grew to enjoy one another’s company). She recalled that on one occasion he opened up to her about his lack of interest in doing further creative work. He told her: ‘you think you have something in your life which makes up for everything and then find you haven’t got it … Two years ago I found this out’.31 The comment almost certainly reveals his devastating awareness that he had lost the love of his wife.32 To be forced to witness the sexual manoeuvrings of others, and their emotional turmoil, would only have deepened Lawrence’s dismay at his own situation.

To pass the time on the island Lawrence read Huxley’s recently published novel Point Counter Point (1928), which appalled and impressed him in equal measure by its frank portrayal of the younger generation. He told Huxley: ‘I do think that art has to reveal the palpitating moment or the state of man as it is. And I think you do that, terribly. But what a moment! and what a state!’ (6L 600). He was similarly appalled by the sections he read from the opening of Aldington’s Death of a Hero: he felt that both men were fascinated by ‘murder, suicide, rape’ (6L 601). Lawrence may have exorcised his anger at Aldington’s behaviour on the island by writing an early version of the poem ‘The Noble Englishman’, in which he indicates that beneath the ‘Don Juan’ aspect of the ‘very normal’ young Englishman is a self-loving ‘sodomist’ whose fear of his own feelings leads him to be spiteful to women (Poems 387–8).

Lawrence also immersed himself in translating a story by the Italian Renaissance writer ‘Lasca’ (Antonio Francesco Grazzini): The Story of Doctor Manente being the Tenth and Last Story from the Suppers of A. F. Grazzini called Il Lasca. This was to be published by Pino Orioli as part of a series of short translations. Lawrence clearly enjoyed working on it; he was able to discuss details of translation, and word choices, with other members of the group, and it was not too taxing, so the work progressed swiftly. It was half finished by 27 October, and almost complete by 1 November.

On 30 October, he received a package of reviews of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, including damning pieces published in John Bull and the Sunday Chronicle. He sat down that evening to go through them with the group. John Bull referred to the novel as ‘a literary cesspool’. Lawrence is said to have responded by saying: ‘Nobody likes being called a cesspool.’ He subsequently stoked up the fire in violent fashion as a form of angry response to all the negative comments.33 Although he thrived on the conflict with publishers and the authorities, and afterwards referred to the cuttings as ‘a babbling of village idiots’ (6L 602), open insults which failed to distinguish his writing from pornography roused a degree of hurt as well as anger and outrage. The unwanted reviews made it impossible for Lawrence to continue keeping the book a secret from his sisters; he was forced to send copies to them, though he advised Emily not to cut the pages of her volume in order to maintain its value.34 After reading it, Ada told Lawrence that she felt he had always hidden part of himself from her; Lawrence responded by telling her that it had never been hidden, but she had refused to see it.35 He soon heard rumours that the novel had been pirated; Charles Lahr confirmed the truth of these a few weeks later.36

On the same day that the reviews arrived, Lawrence had a letter from Nancy Pearn asking for an article for the Sunday Dispatch on the subject of ‘What is Sex Appeal’, and another on ‘England as a man’s country’ for the Daily Express.37 In the following weeks, he would write articles entitled ‘Is England Still a Man’s Country?’, ‘Sex Appeal’ (published in the Sunday Dispatch as ‘Sex Locked Out’), and ‘Do Women Change?’ (which appeared as ‘Women Don’t Change’ in the same paper). Lawrence preferred writing the longer pieces (of 2000 words) for the Sunday Dispatch rather than the 1000 word articles he was accustomed to producing for the Evening News, primarily because it allowed him greater scope to properly explore his subject, but also because he could think of placing the longer articles with Vogue in America. An article in the Sunday Dispatch could take him around an hour and a half to write and earn him £25; in contrast, he received just £165 from Secker for annual royalties on all his books. From a financial perspective alone, it is easy to see why he decided in this period that he would write no more novels after Lady Chatterley’s Lover.38 He would later tell Mabel Dodge Luhan: ‘I put myself on my feet by publishing Lady C. for myself’ (7L 547). The money he gained from it allowed him to invest several thousand dollars in share holdings through the New York branch of Curtis Brown.39

Lawrence had intended to stay at the Vigie until December, but by 8 November the situation on the island was such that he decided to leave. His letters to friends imply that the main reason for his urgent departure was the stormy weather, since they could not get supplies from the mainland when the boats were prevented from setting sail.40 However, the breakdown of relationships and Lawrence’s poor health – and fears for his well-being in the event of further haemorrhages – must have featured strongly in his decision to leave (and in the decision of the others to go too). One of his last acts on the island was to reply to a letter he received out of the blue from David Chambers (the youngest brother of Jessie); his old friend, who was now a Lecturer in Adult Education at Nottingham University College, wrote enclosing a first scholarly publication. Lawrence’s warm reply (which Jessie did not see until after his death)41 looked back nostalgically on his youthful trips to Haggs Farm, and asserted – against the spirit of the letter he had written during Emily’s visit to Kesselmatte – the extent of the continuity between the earlier ‘Bert’ and his current self: ‘whatever else I am, I am somewhere still the same Bert who rushed with such joy to the Haggs’ (6L 618). The acuteness of his yearning for that former self is understandable in the context of his upset over Frieda and Ravagli.

(vi) Bandol and Pansies

The party left Port Cros on 17 November. After a rough crossing, Lawrence and Frieda settled nearby in Bandol, ideally situated on the coast between Toulon and Marseille, on the Côte d’Azur; Aldington and Brigit discreetly stayed on together in Toulon, and Arabella went to Paris. Lawrence was pleased to part from them. He and Frieda took connecting rooms in the Hotel Beau-Rivage, where Katherine Mansfield had stayed for part of her time in Bandol during the war: the rooms were reasonably priced and Lawrence enjoyed the food and was amazed at the warmth of the winter sunshine. Although they only meant to stay for a few weeks (since Lawrence wanted to move on to Spain), they would remain in Bandol until March 1929.

In the first days here he lengthened Rawdon’s Roof for Elkin Mathews and wrote an article for the Sunday Dispatch entitled ‘Enslaved by Civilisation’ (which they accepted but never printed). He also began writing poetry again, producing his Pansies, the often sharp, satirical pieces which he preferred to think of as pensées. Lawrence referred to them as ‘loose’ and ‘peppery’, ‘very modern, written for the young, and quite free-spoken,’ and he was delighted when Frieda called them ‘doggerel’ (7L 64, 122, 110). He may have begun to write these poems during his time on Port Cros, but it was only in Bandol that he truly warmed to the task: he had written over 160 poems by 20 December. Rhys Davies, the Welsh writer who first visited the Lawrences in Bandol between 29 November and 2 December, noted how Lawrence would write the poems in bed in the mornings, and then go out at around 11 or 12 o’clock and stroll along the seafront, spending the afternoon and evening relaxing.42 ‘Desœuvrée’ became one of Lawrence’s new keywords: he felt at a loose end, ‘a bit unstuck from the world altogether’ (7L 119, 71), but this was the perfect frame of mind in which to launch provocative attacks on the ways of the modern world. He filled some of his time in late November going through the typescript of a new novel by Mollie Skinner entitled ‘Eve in the Land of Nod’, which she had sent on to him in the hope that he could work on it as he had done with ‘The House of Ellis’, but after making extensive efforts to re-structure it he decided that he was too far removed from the material to pull it off: ‘How can I re-create an atmosphere of which I know nothing?’ (7L 36).

His poems provided one outlet for his sardonic mood, but he also found time in his new daily schedule to write a further article entitled ‘Oh these Women!’ in response to a cutting from a piece in an American magazine, sent to him by the Daily Express. Lawrence’s article opened with a provocative assertion – ‘The real trouble about women is that they must always go on trying to adapt themselves to men’s theories of women, as they always have done’ – but it went on to criticise ‘modern men’ for not knowing what they want women to be, and for offering them ‘ready-made, worn-out, idiotic patterns to live up to’ (LEA 162, 165). Vanity Fair published the article in May 1929 under the title ‘Woman in Man’s Image’; it did not appear in the Daily Express until 19 June 1929, as ‘The Real Trouble About Women’ (the essay is now better known as ‘Give Her a Pattern’). In America it raised a protest from four businesswomen who expressed outrage at Lawrence’s suggestion that women tend to adapt themselves to men’s ideas of them. Lawrence wrote a dry response to their letter, which was calculated further to infuriate his readers: ‘the ladies do protest too much. They are still acting under male suggestion – only this time, falling over backwards’.43

As Christmas approached, Lawrence had a number of problems to confront. He was attempting to claim back (from Thomas Seltzer and others) the copyright for his volumes of poetry in America, with a view to releasing an edition of his Collected Poems over there.44 According to his own calculations, by 14 December Lady Chatterley’s Lover had made a £1024 gross profit for himself and Orioli.45 However, Alfred Stieglitz in New York had now corroborated Charles Lahr’s account of the free circulation of pirated editions, proving that they were being sold on both sides of the Atlantic; initial reports suggested that two pirated editions were selling for 30 shillings and three guineas respectively.46 Lawrence asked the Huxleys in Paris to check whether pirated editions were on sale there, and he was horrified to learn that Maria had been offered a pirated copy in the librairie Castiglione for the princely sum of 5000 francs.47 His first thought was to undercut the pirates by releasing the 200 unsigned, paper-bound volumes onto the market for £1, though the small number of copies available to him made it highly unlikely that this would have the desired effect.48 Charles Lahr proved very helpful in distributing them: he bought over 100 copies at the cover price of one guinea per book (selling them to trade at 24 shillings and to private individuals at 30 shillings).49 The only other option seemed to be releasing a popular edition, but Lawrence felt unsure about approaching the two leading candidates to publish it (Victor Gollancz and Sylvia Beach).

The other area for concern was his paintings, 24 of which were now with Dorothy Warren at her gallery in London; Lawrence was irritated by her tardiness in arranging the opening of the exhibition, which was further delayed until the new year. While in Florence, Frieda had made contact (through Orioli) with a 28-year-old Australian named John (‘Jack’) Lindsay, who had come to London in 1926 to set up a publishing company called the Fanfrolico Press, managed by another young Australian, P. R. Stephensen. The two men had recently launched a magazine entitled the London Aphrodite as a challenge to J. C. Squire’s London Mercury. They expressed strong interest in publishing a volume of Lawrence paintings. Lawrence was extremely enthusiastic about the idea, and his enthusiasm only increased when Stephensen came to Bandol for two days from 18 to 19 December (accompanying Rhys Davies at the start of his second visit). The young man turned out to be ‘very nice and simple’ (7L 76); he discussed Lawrence’s paintings with relish. He also reassured Lawrence that Charles Lahr was a reliable individual, and he expressed interest in publishing Kot’s recent translation of V. V. Rozanov’s Fallen Leaves. In a subsequent letter to Stephensen, Lawrence asked whether they could avoid using black-and-white collotype to reproduce his paintings and go for colour instead; it was agreed that they would issue 500 copies of a deluxe colour volume and sell it for 10 guineas. Lawrence asked Orioli to send Stephensen a list of all known subscribers to the Florence edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, so that they could send out prospectus forms to those individuals; he accepted £250 for rights to reproduction and 5% royalties, mainly to avoid paying more money than necessary in taxes to the British government.50

Stephensen was really the driving force behind the venture: in February 1929, he would go into partnership with the London bookdealer Edward Goldston and form a separate company, the Mandrake Press, which would see the project through. Lawrence was so positive about it that he immediately started work on an introduction, setting his own ambitions as an artist joyfully celebrating the human form in the context of a post-Renaissance Western art which he felt had been damagingly preoccupied with landscapes and abstraction. At Lawrence’s request, Kot sent him copies of Roger Fry’s Cézanne: A Study of His Development (1927) and Tolstoy’s What is Art? (1897),51 but he also took it upon himself to send on Clive Bell’s Art (1914), since he knew that Lawrence was an enemy of Bell’s idea of Significant Form. Lawrence began writing ‘Introduction to These Paintings’ around Christmas time; it would be finished by 12 January 1929. In the meantime, during his months in Bandol, he would produce two more oil paintings (‘Dance Sketch’ and ‘Summer Dawn’), four watercolours (‘Leda’, ‘Singing of Swans’, ‘Spring’, and ‘Renascence of Man’), an endpiece illustration for the volume of paintings, plus another illustration for a planned volume of aphrodisiac recipes to be edited by Norman Douglas and published by Orioli.52

‘Introduction to These Paintings’ was not the only introductory essay which Lawrence began writing in December 1928; he also started work on his introduction to Pansies, which went through four versions between December and 27 April 1929. The offhand and frequently barbed, satirical nature of the poems enabled Lawrence to exorcise his irritation on a number of trivial and more wide-ranging topics, from Huxley’s depiction of him as Mark Rampion in Point Counter Point and Aldington’s Oxford accent on Port Cros to modern censorship, the romantic allure of cinema, the pretentiousness of the middle classes, and the state of workers in a mechanised workplace. Lawrence sent several of these poems to friends whom he felt would take a particular interest in them. He sent ‘No! Mr Lawrence!’ to Nancy Pearn on 15 December (an ironic reflection, perhaps, on Curtis Brown’s opposition to his publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover).53 Stephensen received ‘My Naughty Book’, about the public reception of the novel; Juliette Huxley was sent ‘Henriette’, a poem about her changing attitude to it; and Charles Wilson was sent five poems to pass on to the Durham miners as a form of New Year greeting, including ‘For God’s Sake’ (about the mechanisation of the workplace) and ‘O! start a revolution!’54

Christmas 1928 was quieter than the previous two years at the Villa Mirenda, in spite of the Beau-Rivage filling with French holidaymakers. Lawrence rather enjoyed being alone much of the time and having just a few sympathetic souls to visit, but Frieda was more unsettled.55 She missed having a house of her own, and longed to move back to Lake Garda or Taormina; she hoped that her daughters would be able to join them for the festivities, but Elsa was too busy with work, and Barby’s trip to Bandol was eventually postponed until 2 January. Rhys Davies left on Christmas Eve. Lawrence and Frieda went to see a ‘pastorelle – a sort of semi-Christmas play, in dialect – very amusing’ (7L 116), but otherwise the days passed by uneventfully. Lawrence even finished writing an essay on Christmas Day. ‘New Mexico’ was a piece which Mabel Dodge Luhan had arranged for him to write for Survey Graphic; its celebration of the majesty of the New Mexican landscape is deeply nostalgic. The last stay at the ranch had been a time of healing: the self-sufficiency of the life he had established there with Frieda was something he looked back on with great affection and longing. He often expressed a wish to go back, and made intermittent plans to travel, but he must have realised at some level that his health would not allow it.56

It snowed in Bandol early in January, and the drop in temperature was accompanied by a strong wind which made Lawrence fearful for his health. However, if he and Frieda had passed a quiet Christmas, they certainly made up for it in the new year. Barby duly arrived for a 10-day visit: she had been feeling rather depressed in London (a condition which Lawrence ascribed to her mixing with the wrong sort of Bohemian set).57 There were other visitors, too. On 4 January, a 25-year-old American named Brewster Ghiselin came to see Lawrence. Lawrence told Huxley that admirers usually had a ‘depressing effect’ on him; ‘Bruce’, as Ghiselin was known, evidently thought of himself as a ‘disciple’,58 but Lawrence found him ‘really nice’ (7L 118) and invited him to move from his nearby hotel into the Beau-Rivage. The handsome young man took an active interest in painting, so Lawrence showed him his own work and discussed his recent writings on art. His visitor was even hardy enough to swim in the sea during his time in Bandol. When Stephensen dropped by from Nice on 7 January to discuss plans for the edition of the paintings, he would have entered a far livelier environment than he or Rhys Davies had experienced before Christmas. Only on 15 January, once Brewster Ghiselin had left, did the Lawrences have a little time alone again.

(vii) Confiscated poems

Lawrence sent two typescripts of Pansies to Laurence Pollinger by registered mail on 7 January; a week later, he sent ‘Introduction to These Paintings’ in the same way. By 18 January he was starting to worry that Pansies had not arrived.59 He was angry that Orioli had recently distributed by post a provocative collection of limericks by Norman Douglas, which had attracted the attention of the English police; he felt that this might prove ‘bad for everybody else’ (7L 142). That very afternoon, Pollinger received a visit from two Scotland Yard officials who informed him that they had seized six copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover recently sent to him by Orioli; they told him that further copies would be seized and destroyed.60 Lawrence did not hear about this until 21 January (the day Aldous Huxley and Maria arrived for a brief visit). Brigit Patmore’s son Derek soon reported that ‘a detective sort of fellow’ (7L 151) had called by and asked for his mother (who was away in Italy at the time); shortly afterwards, Lawrence learnt that his typescripts of Pansies had been confiscated in the post, and ‘Introduction to These Paintings’ was also being examined (though, thankfully, this manuscript was soon released, much to Lawrence’s relief since it was an only copy).

Lawrence’s reaction was typically courageous and belligerent: he vented his outrage to the Huxleys, but decided simply to re-type Pansies, altering some poems and adding others as he went along. He purchased another notebook in Bandol, in which he wrote the new poems. He also pushed on with plans to publish the volume of his paintings: he gave the go-ahead to Stephensen after seeing a proof reproduction in colour of ‘Accident in a Mine’, which was fairly good, if not ideal.61 He had earlier expressed anger at the moral crusade undertaken by the Home Secretary, Sir William Joynson-Hicks (or ‘Jix’, as he was popularly known), and he was keen to contest the authorities’ grounds for their withholding of his typescripts.62 Huxley recommended that he contact St John (‘Jack’) Hutchinson, a barrister who was about to stand as a liberal MP for the Isle of Wight at the next elections. Through Hutchinson and his friend, Oswald Moseley, and with the help of the Curtis Brown solicitors, Lawrence would successfully push to get questions raised about the confiscation of Pansies in a debate in the House of Commons on 28 February, though Joynson-Hicks answered these with downright untruths, claiming that the packages had been opened as part of a standard check on open mail, when they had both been sent via registered post.63

This was a difficult period for Lawrence. Although he continued to enjoy the relaxed nature of life in Bandol, at times he despaired about the state of the literary world. He particularly felt that the admiration he received from the younger generation – and the freedom of expression that he was gradually winning for it – did not translate into practical support. He told Ottoline Morrell: ‘Those precious young people who are supposed to admire one so much never stand up and give one a bit of backing’ (7L 165). Murry’s recent review of Collected Poems in the Adelphi had referred to Lawrence as ‘a creature of another kind,’ with a ‘sixth sense’, which made him feel as if he were being presented as a ‘freak’ (7L 166). Even a comical cartoon by ‘Low’ in the Evening Standard for 26 February, entitled ‘Jix, the Self-Appointed Chucker-Out’, singled him out, showing him arguing alone with a burly policeman outside ‘The Literary Hyde Park’ while a number of other literary figures (including Huxley, Joyce and H. G. Wells) depart with their respective literary muses.64 Although Lawrence insisted that his own position was the natural one in arguing for freedom of expression, it was understandable that he should feel marginalised and beset: he even believed that he might be arrested if he went back to England.65

On 11 February, he sent a typescript of Pansies to Marianne Moore, hoping that the Dial might be prepared to publish some of the poems; Moore would print 11 of them in total. The next day his sister Ada arrived in Bandol for a 10-day holiday. Lawrence was always more temperamentally attuned to Ada than Emily, but on this visit her restlessness left him feeling depressed. She seemed uninterested now in the things that had always given her life meaning: ‘business, house, family, garden even.’ Reflecting on her earlier reaction to reading Lady Chatterley’s Lover, he felt that it was a consequence of her having been ‘too “pure” and unphysical, unsensual’ (7L 213, 214) throughout her life. By the time she left, on 22 February (taking ‘Spring’ and ‘Summer Dawn’ back with her, to give to Dorothy Warren), the cold weather had killed a good many of the palm and eucalyptus trees in Bandol, so the desolation around them matched the feeling of misery he sensed in her. Ada would return in time to witness the death of her father-in-law. It was a terrible situation, and Lawrence (always mindful of members of his family and their feelings) took this opportunity to pay her and Eddie back £50 of the money they had spent in renting Mountain Cottage for him back in 1918.66

Just as he had written ‘Red Trousers’ after Emily had left Kesselmatte, so now he wrote an article entitled ‘The State of Funk’, attacking England for responding to great and radical changes in the times with ‘horrible fear and funk and repression and bullying.’ Lawrence put the case for an open acceptance of sexuality as a means of offsetting unhappiness and restoring ‘the natural flow of common sympathy, between men and men and men and women’ (LEA 223). He sent the piece to Nancy Pearn on 1 March, but (in the charged atmosphere of the time) she held it back and it was never published in Lawrence’s lifetime. In the same package he included an introduction he had written to the novel Bottom Dogs (1929) by a struggling young American writer named Edward Dahlberg, who was being supported by Arabella Yorke in London; it was another instance of his kindness to a younger generation of authors.

On 28 February, Lawrence had sent to Secker what he described – purely for the sake of the authorities, in anticipation of them opening his mail – as an ‘expurgated’ (7L 195) version of Pansies. However, if he had toned down the introduction to the volume and omitted and revised some of the poems, he had also added further poems, and in due course he would arrange for Rhys Davies to send on the excised poems under separate cover.67 He defiantly informed Secker that he would not ‘haul down my flag … for all the Jixes in Christendom’ (7L 249).

Lawrence now wanted to escape to a warmer climate. He thought about taking a house in Corsica, but accounts of the cold weather there put him off.68 A visit to Toulon to order a new suit had left him feeling unwell and caused him to give up all hope of visiting America for another year. His idea was to travel instead to Majorca, but a letter he received from Frank A. Groves, offering to help distribute a cheap Paris edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, led to a late change of plans. Bringing out a pocket edition of his novel would at least enable him to fight back against the publishers of pirate editions: conflict was the one thing which he had always seen as necessary for his well-being. After Rhys Davies arrived in Bandol on 4 March, Lawrence decided to travel with him to Paris to organise its production. Frieda took the chance to visit her mother in Baden-Baden (perhaps going to see Ravagli at the same time).

(viii) Paris

They left Bandol on 11 March, and Lawrence and Davies arrived in Paris the following day. The city struck Lawrence as cold, dark and grey; his health had suffered during the journey, so his first impressions of it were not good. Nevertheless, he made arrangements to visit Harry Crosby and his wife Mary (better known as Caresse) at their luxury apartment to discuss the possibility of them publishing the full version of The Escaped Cock. Although Harry expressed interest in Lawrence’s novella, the lunchtime meeting on 15 March exposed serious differences in outlook between the two men: Harry evidently disliked Lady Chatterley’s Lover and thought Lawrence too ‘engrossed in the body,’ while one can only guess at Lawrence’s objection to the younger man’s ostentation and insistence on his own ‘visionary’ qualities.69

A meeting with Groves revealed the surprising terms of his interest in Lady Chatterley’s Lover: he had acquired 1500 pirated copies of the novel and offered Lawrence the opportunity to authorise these copies and sell them through respectable booksellers, taking 20% of the profits. Lawrence considered the offer for a time, but then declined it. He went to see Sylvia Beach to check whether she had any interest in printing a private edition; she did not, but directed Lawrence to approach a wealthy American bookseller named Edward Titus. Titus would finally agree to print 3000 copies which would be sold at 60 francs to the public and 40 francs to trade. The edition would cost 30,000 francs, which they agreed to split between them. It would soon earn Lawrence as much as the Florence edition.

On 18 March, having seen Edward Dahlberg in the city, Lawrence headed out to stay with the Huxleys at their house in Suresnes. He found the place comfortable, and Maria in particular looked after him very well at a moment when his health was at a low point. The Huxleys encouraged him to see a doctor, and they arranged a second appointment during which he would be X-rayed (though he backed out of this at the last moment). The French doctor discovered that one lung was effectively hopeless and the other badly affected.70 Maria recommended that Lawrence should travel to Holland and put himself in the care of a doctor she knew there. She was so concerned about his health that during a subsequent visit to England she told people that he was dying. Aldous’ similar fears for his well-being also got around; J. W. N. Sullivan reported them to Murry, who swiftly wrote to Lawrence asking to meet him, but his approach was definitively rebuffed.71 Lawrence did, however, arrange to speak with Glenn Hughes, an American professor busily researching a book on Imagism: during their meeting on 25 March, Lawrence told Hughes that the movement was ‘an illusion of Ezra Pound’s, … and was nonsense.’72

That evening Frieda arrived in Paris and Lawrence moved with her to a hotel. Titus had suggested that Lawrence should write a ‘peppery foreword’ (7L 229) to their Paris Popular Edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and he set to work to do this, finishing the piece (entitled My Skirmish with Jolly Roger) by 3 April. He was anxious to leave Paris and head to Spain, but there was a further meeting with Dahlberg on the evening of 28 March, and on the weekend of 29 March to 1 April he and Frieda went to stay with the Crosbys at ‘Le Moulin du Soleil’, the mill which they rented at Ermenonville, 30 miles north of the city. In the course of their stay, Crosby played Lawrence a rare recording of Joyce reading from the Aeolus section of Ulysses.73 Lawrence was unimpressed by it, but Frieda took a liking to the Crosbys’ gramophone, and especially to a recording of Bessie Smith’s ‘Empty Bed Blues’. Lawrence became so exasperated that he broke this record (and perhaps others) over her head. Later, Crosby would send Frieda her own gramophone, much to Lawrence’s disgust.

Rhys Davies left for England on 2 April, in the company of his mother and sister, taking with him ‘the complete Ms.’ (7L 233) of Pansies to give to Charles Lahr for safekeeping. The next day Lawrence and Huxley saw the Crosbys again; this time they argued over Joyce, with Huxley joining Lawrence in disputing Joyce’s achievements. The Crosbys had to leave their meeting to see Joyce and sign a contract with him to print further instalments of his ‘Work in Progress’. When they offered him the chance to meet Lawrence, he declined, on the grounds that his eye was hurting him.74 Lawrence was, in any case, too preoccupied with his own publishing ventures. After his meeting with the Crosbys he arranged for the complete text (parts one and two) of The Escaped Cock to be sent to them, and on 5 April he signed the agreement with Titus for Lady Chatterley’s Lover. At some point he also met Albert Boni, one of two brothers who had taken over the publishing business of their uncle, Thomas Seltzer. Boni had contacted Laurence Pollinger to enquire about the possibility of bringing out a new uniform edition of Lawrence’s works in America, and offered to pay off Seltzer’s outstanding debts to Lawrence of around $4000. Lawrence was willing to discuss the publishing scheme, but he found Boni ‘a bit furtive’ (7L 521), and when he came back to Lawrence’s hotel room and offered to write him out a cheque for $1000 as part payment of the outstanding debt, Lawrence refused to accept it. He ultimately decided to wrest back control of his books from Seltzer and Boni. The untidy nature of his publishing arrangements in America continued to trouble and irritate him.

(ix) Spain, and Majorca

On 7 April, Lawrence and Frieda left Paris to travel in stages to Carcassonne, via Orléans and Toulouse. They arrived on 9 April, briefly staying at the expensive Hotel de la Cité before travelling on through Perpignan to Barcelona. During his travels Lawrence received a request from Studio for an essay on painting: by 15 April, a day or so after he had settled into the Hotel Oriente in Barcelona, he sent Nancy Pearn ‘Making Pictures’, a piece which set out the nature of his own engagement with painting, from his early love of copying works in watercolour through to his recent work in oils. It was a perfect way to advertise both the exhibition and Stephensen’s forthcoming volume of his paintings. In the coming weeks, Lawrence would take a close interest in the photographic reproduction of the paintings, asking Stephensen for further proofs as they became available and commenting in a painstaking fashion on how they might be improved. The venture clearly meant a great deal to him, and he was impatient to see the finished volume.

He was equally preoccupied with the publication of Pansies. His outrage at Joynson-Hicks’ confiscation of his typescripts, and at the failure of all attempts to make the Home Secretary own up to the illegality of the seizure,75 made Lawrence more determined than ever to get the unexpurgated text into print. Secker irritated him greatly by expressing anxiety about individual phrases in poems (he particularly pointed out a reference to ‘cat-piss’ in ‘The Saddest Day’ and ‘pee’ in ‘True Democracy’).76 Although Lawrence offered to write another, shorter foreword for the volume, he demanded to know exactly what changes Secker wished to make to the collection, and which poems he intended to cut from it: he vehemently resisted any attempt to make it ‘respectable’. He even considered printing some of the more controversial poems in a broadsheet to release in time for the general election in England on 30 May 1929.77 He told Laurence Pollinger that he was ‘a black sheep that refuses to be whitewashed all over – must at least be piebald’ (7L 257). In the end, Secker would request certain changes, plus the omission of 14 poems.78 Lawrence only acceded to these in full once he knew that Charles Lahr was interested in bringing out an unexpurgated edition, and even then he fought Secker over the terms of the contract, demanding ‘one-third the profits accruing merely from the signing’ (7L 267) of the special limited edition copies. Lawrence would eventually negotiate with Secker and Lahr to publish 500 unexpurgated copies of Pansies in August 1929, the month after the publication of Secker’s ‘expurgated’ volume. The edition was printed and distributed by Lahr, but it was Stephensen’s name which appeared on the title page.

After spending just a few days in Barcelona, Lawrence and Frieda took an overnight crossing to Palma de Mallorca. The day after their arrival, Lawrence saw the poet Robert Nichols in the street. It was the first time they had met since the war, and Lawrence enjoyed re-establishing connections with Nichols, and with his wife, Norah Denny; through them, he would gain valuable introductions to the expatriate community on the island. After five days, Lawrence and Frieda moved to the Hotel Principe Alfonso, where they remained for the duration of their two-month stay on Majorca. Lawrence was initially rather ambivalent about the place: he enjoyed its Mediterranean climate, but found it expensive and less beautiful than Sicily. He could not tell whether the place was a quiet haven or boring and dull,79 but after an outbreak of fever shortly after his arrival his health picked up and he decided that it would be a good place to stay, at least until the summer heat forced him to move on.

Although Lawrence told Nancy Pearn that he felt no desire to work on Majorca, he did write more than 50 new poems in the notebook he had bought in Bandol, and he produced another essay and article. The essay, which he finished by 29 April, was entitled ‘Pornography and Obscenity’; it was produced for This Quarter, a journal which Edward Titus was re-launching in Paris. This provided an opportunity for Lawrence to question conventional definitions of pornography. He argued that obscenity lies not in explicit descriptions of sex, but in more suggestive texts which cause the mind to dwell on sexual feelings not brought out into the open: ‘Boccaccio at his hottest seems to me less pornographical than Pamela or Clarissa Harlowe or even Jane Eyre or a host of modern books or films which pass uncensored.’ In an even more provocative aside, he extends his list of suggestive texts to include ‘some quite popular Christian hymns’ (LEA 240). He wrote the article ‘Pictures on the Wall’ in response to a request from the editor of the Architectural Review for a piece on artists and decoration; it was finished by 1 May, but not published until February 1930 (it appeared first in Vanity Fair in December 1929). It too is radical and iconoclastic in its suggestion that there should be an Artists’ Co-operative Society formed to lend or sell framed prints to members of the public, allowing them to regularly change the images they live with in line with transformations in their personality and outlook. Lawrence asserts that people should ‘rigorously burn all insignificant pictures, frames as well’ (LEA 257) in order to breathe more freely at home.80

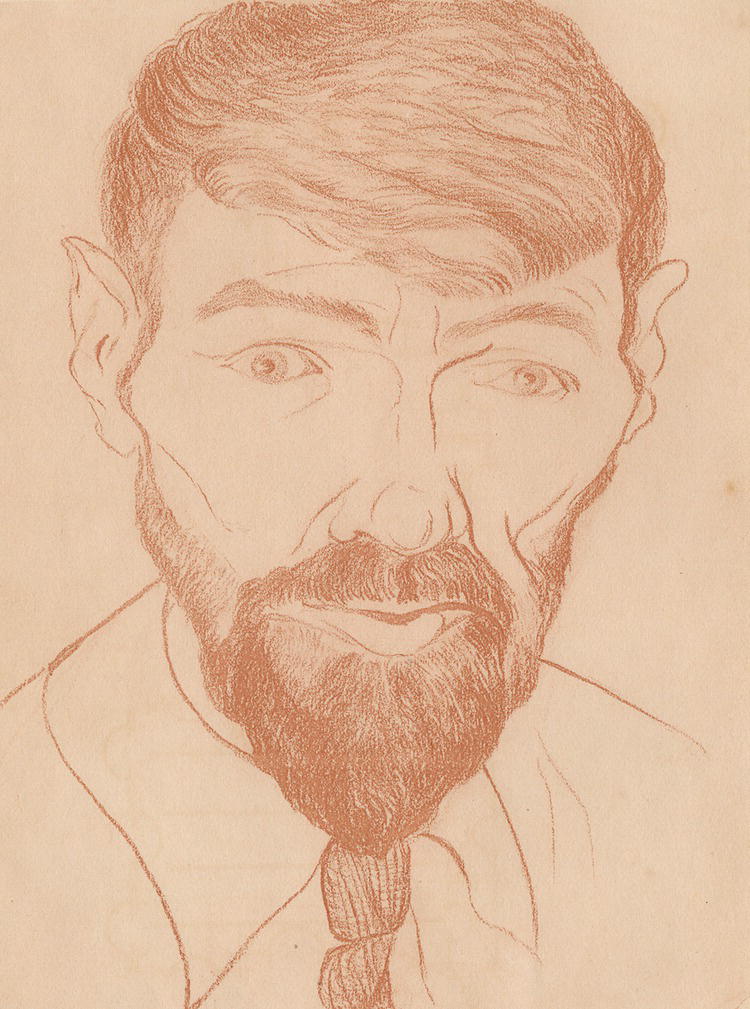

Figure 16 D. H. Lawrence, self-portrait in red crayon, June 1929. First published as the frontispiece to the unexpurgated edition of Pansies.

The other interesting work Lawrence produced on Majorca was a striking self-portrait in red crayon. Charles Lahr had requested either a photograph or a drawing of Lawrence to use as a frontispiece to the unexpurgated edition of Pansies.81 Lawrence arranged a session with a local photographer, Ernesto Guardia, and sat for an artist named Tom Jones. However, he was not satisfied with the drawings of him, which captured him in a seated position. The photographs are fascinating, but they show Lawrence in a relaxed and gentle, reflective mood.82 Lawrence’s own self-portrait reveals a far more confrontational and unflinching figure, facing straight out from the page in a defiant pose. The stylised image is reminiscent of Van Gogh, and there is something almost Pan-like in the pointed ears. Lawrence told Lahr that he preferred his own sketch, saying ‘I think it is basically like me’ (7L 333). It was certainly the image best suited to the tone of the poems, so this was the one which Lahr reproduced in Pansies. Lawrence insisted that Lahr should also reproduce his phoenix image on the cover, since he wanted this to appear ‘on all my private issues’ (7L 336).

Early in May, Frieda urged Lawrence to begin looking for a house which they could rent for several years and use as a permanent base.83 She still wanted to move back to Italy, so they considered the places they knew, or areas close to friends: Lake Garda, Florence, or somewhere around Forte dei Marmi. Lawrence had been forced to consider selling the Kiowa Ranch, but the thought of giving it up was painful: ‘like parting with a lovely stretch of one’s youth’ (7L 288). By the end of the month, with nothing decided about either the ranch or a new European home, their only plan was to leave Majorca, take the boat to Marseille and travel on to Italy. However, a series of delays (occasioned in part by Frieda badly spraining her ankle) meant that by the time they left, on 18 June, the exhibition of Lawrence’s paintings had already opened in London (the private viewing took place on 14 June) and he had received a copy of the book of his paintings from Stephensen.84 It was decided that Frieda should travel to England to see the exhibition and make arrangements for what would happen to the paintings afterwards, while Lawrence went on to Forte dei Marmi, where he could spend a few weeks living close to the Huxleys. He arrived at the Pensione Giuliani on 22 June.

(x) ‘Succès de scandale’

In London, Frieda had her ankle treated by a specialist and was able to see her children again. She was tasked with overseeing Lawrence’s literary affairs, both during her journey and on her arrival. In Paris, she met with Edward Titus and took away a pristine copy of the new Paris Popular Edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which he was just starting to circulate, and in London she personally delivered Lawrence’s self-portrait to Charles Lahr. She spent a ‘coruscating fortnight’ in England, being ‘fêted and champagned and made a fuss of’ (7L 367, 373). Overseeing the exhibition proved to be the greatest adventure. During its opening week it had attracted 3500 visitors.85 Its popularity was reflected in advanced sales of Stephensen’s Mandrake Press edition of the paintings: by 23 June, all 10 of the special edition copies on Japanese vellum at 50 guineas had been sold, and 300 of the 500 normal copies (at 10 guineas) had been snapped up. The entire edition would be sold out by 13 July.86 Yet, reviews of the exhibition, beginning with a notice in the Observer for 16 June, were predictably negative. It was clear that the show was going to be a ‘succès de scandale’ (7L 385), and that it would attract the attention of the authorities, in spite of the fact that Labour had won the election and Joynson-Hicks had been replaced as Home Secretary.

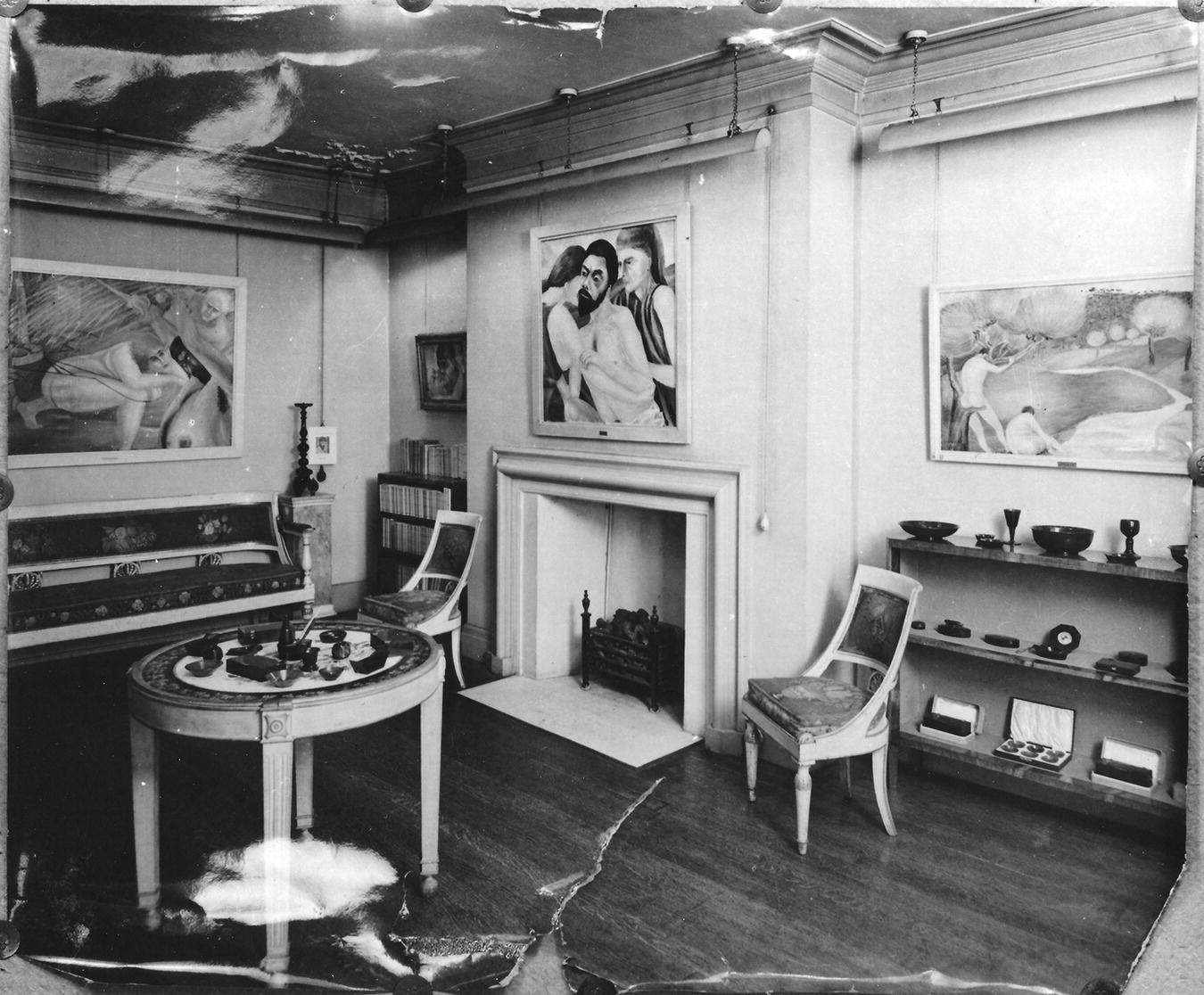

Figure 17 Lawrence’s paintings hanging in the Warren Gallery, London.

(Photography Collection, D. H. Lawrence Literary File P-591, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.)

On 4 July a party was thrown at the Warren Gallery: it was a ‘reception given for Frieda’ and it provided an opportunity to celebrate the paintings.87 It was attended by, among others, Catherine Carswell, Stephensen, Ada, and Willie Hopkin. Around four o’clock the next day, two detectives showed up and asked Dorothy Warren and her new husband, Philip Trotter, to close the exhibition. They refused, but the men returned with policemen an hour later and confiscated 13 of the 25 paintings. They initially turned the offending images to the wall, but were forced to oblige the Aga Khan by turning ‘Contadini’ back again when he and a fellow visitor requested to see it.88 The police subsequently impounded the paintings in a prison cell at Marlborough Street; at the same time, they confiscated four copies of the Mandrake Press edition of the paintings (one of them a valuable vellum copy), plus a portfolio of paintings and drawings by Georg Grosz which had been left in the gallery. They almost took away a book of William Blake’s pencil drawings, too, before the intercession of a member of the public. On 9 July, Frieda attended a meeting at which she, Dorothy, Philip Trotter, and St John Hutchinson and Percy Robinson (the lawyers acting on behalf of the gallery and Lawrence respectively) plotted a line of approach to the situation. Dorothy and Philip agreed to keep the exhibition open, filling the spaces with some of Lawrence’s early watercolours, which they acquired from Ada. It was clear that to get the 13 confiscated paintings back they would either have to take an appeal to the High Court, thus risking having them destroyed by the authorities, or else try to establish a settlement which would secure their return in exchange for a promise never to show them in Britain again. On 12 July Dorothy Warren was called upon to provide reasons why the paintings should not be destroyed; fortunately, the hearing was adjourned until 18 July, and then until 8 August to allow the Detective Inspector in charge of the case to take his summer holiday.

Meanwhile, Lawrence had settled into life in Forte with surprising ease, given his general dislike of the beach life which had attracted the Huxleys to the area in the first place. He was not, of course, able to bathe; he would have been very conscious of the health problems he had experienced as a result of doing so the last time he was here, in June 1927. Yet, his room in the pension was reassuringly similar to the Villa Mirenda, and he found the place quiet and cool. On his arrival, he made arrangements for Pino Orioli to visit for a weekend, and he was visited by a Mexican admirer now living in New York named Maria Cristina Chambers. In the fullness of time, she would prove to be an energetic ally on the opposite side of the Atlantic, but for now she irritated Lawrence, reminding him of the worst qualities in Arabella Yorke, and in Ivy Low, a female acolyte who had stayed in Fiascherino back in 1914.89

On 7 July, Lawrence moved on to Florence, to stay with Orioli. Maria Huxley drove him to Pisa where he caught a train; on his arrival in Florence he looked so unwell that his host ordered a car to get him back home. Orioli then telegraphed Frieda to ask her to return. Lawrence’s health had received another setback, and he was confined to bed for two days, suffering from a sore chest and fever. He described it as a ‘nasty cold’ (7L 363), but it was evidently another flaring up of his tuberculosis; he would variously put it down to drinking ice-cold water in Forte, and to sitting too late on the beach.90 After 9 July, when he heard of the police confiscation of his paintings, he would also ascribe the downturn in his health to ‘their beastliness in London reaching out to me’ (7L 364).

Frieda arrived in Florence on the evening of 11 July; they moved together to the Hotel Porta Rossa. A few days later, Lawrence decided that the best course of action was to compromise and offer never to show the paintings in Britain again in order to secure their return. He was not prepared to sacrifice his works simply on the chance of securing a change in the censorship laws. He arranged to give ‘North Sea’ to Maria Huxley as a gift, and for Orioli to buy ‘Dandelions’, and he gave both Enid Hilton and St John Hutchinson the option to own one of the paintings.91 The strain, however, made him feel ‘irritated and fed up’ (7L 375). He had the impulsive idea of offering the first version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover to Secker and Knopf, but the offhand manner in which he described his reasoning to Orioli – ‘I believe it has hardly any fucks or shits, and no address to the penis, in fact hardly any of the root of the matter at all’ (7L 383) – revealed his irritation at having to think about the tender sensibilities of a mainstream readership.

(xi) Plättig

On the evening of 16 July, when he was well enough to travel, he and Frieda left for Baden-Baden where they were to celebrate his mother-in-law’s seventy-eighth birthday on 19 July. They put up again at the Hotel Löwen in Lichtenthal, and Lawrence enjoyed his usual visits to the Kurhaus, but a subsequent stay with the family from 23 July in a nearby Black Forest spa hotel in Plättig, perched at the top of a mountain at an altitude of 2600 feet, made him thoroughly miserable. His health had only just begun to recover, and in the new hotel he caught a cold and was confined to bed, while the Frau Baronin grew stronger and stronger, seeming to pay little attention to his plight. It was the first time that his affection for his mother-in-law had been so sorely tested: he found her selfishness ‘really rather awful’ (7L 397) and felt that she was sacrificing everything (and everybody) to hold off her own fear of death.

Lawrence spent part of the time in bed starting to translate the first story from the Second Supper by Lasca (in Florence he had managed to write a short introduction to The Story of Doctor Manente, which Orioli was preparing to publish).92 He released some of his anger and irritation by beginning to write a rather sharp short story about a strong-willed woman who decides to leave her husband for one year in order to discover ‘her own rare and magical self’ (VG 253) in a hotel at the top of a mountain in her mother’s home country, only to find it rather cold and terrifying;93 he also wrote a number of stinging poems (or ‘Nettles’) about his critics and the attitude of the people who had been to see his exhibition.94 In a quite different mood, he produced a short article for the magazine Everyman entitled ‘The Risen Lord’, on the topic of ‘A Religion for the Young’. In it, he argues that the young lack any living connection to Christ since available religious iconographies are mainly anachronistic. In the pre-War years Christians had been attracted to the innocent image of the Virgin and the baby Jesus, while during the War they rallied around the crucifixion. Lawrence calls for a new awareness of the Risen Lord as a figure in the flesh, who ‘rose to know the tenderness of a woman, and the great pleasure of her, and to have children by her’ (LEA 271). The essay implicitly promotes the vision of Christ he had explored in The Escaped Cock, whose full text would shortly be published by the Crosbys’ Black Sun Press (with reproductions of four small watercolour decorations and a watercolour frontispiece, all by Lawrence). He would attempt a similar defence of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in October, when re-writing and developing My Skirmish with Jolly Roger – which had been published by itself in a slim but expensive volume by Random House in America – into A Propos of ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’, for the Mandrake Press and the British market.

(xii) Writing for an ‘improper public’