THE MOVES

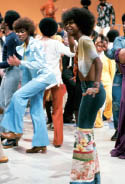

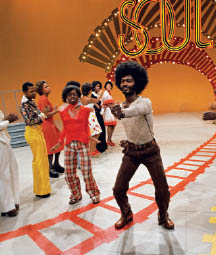

When I was growing up, Soul Train was cool, and cool was Soul Train. This was well before the dawn of the VCR, so the only way you could ensure that you remembered everything about a Soul Train episode was to, well, remember everything. This was doubly true for the dancers. My cousins and I would watch them closely, as intent as any scientist in the field. “You all see that?” one of us would say, shoving the others to attention. “You all see that?” We’d look around to make sure we hadn’t seen it wrong and then head to the mirror to practice. After the show, we’d go out into the street to show off our new moves, where we discovered that most everybody in the neighborhood had the same idea.

Don once stated that the Soul Train Dancers were always intended to be the “true stars of the show.” Whether or not he was able to book the big-name musical acts, he could always count on his dancers, in all their magnetic and stylish glory, to entertain, inspire, and wow the viewers. As it turns out, the unintentional modus operandi of Soul Train was to feature an act on its rise or on its descent, but never while at the top of its game. So ultimately the dancers were the ones who left indelible marks on the audience.

Season 1 Dancers

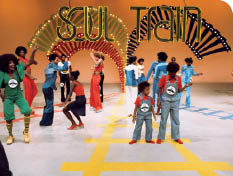

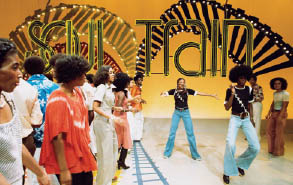

From 1971 to 1975, the dancers were called the Soul Train Gang, but as the word gang took on a negative connotation, Don changed the name to the Soul Train Dancers. He did, however, repurpose Soul Train Gang for a soul music group that he and Dick Griffey formed in 1975 for Soul Train Records.

According to Don, Soul Train was first and foremost a dance show, so he sought out people who looked good on camera and danced well. But when Don arrived in LA and began meeting the kids who eagerly auditioned their contortions, acrobatics, and funky “street” dance styles, he realized that he got much more than he bargained for—and in a good way.

MEET THE CAST

• Charles “Robot” Washington

• Pat Davis

• Thelma Davis

• Damita Jo Freeman

• Jimmy “Scoo B Doo” Foster

• A dance troupe known and named for its pop-and-lock moves, the Lockers included Don “Campbellock” Campbell, Leo “Fluky Luke” Williamson, Adolfo “Shabba Doo” Quinones, Greg “Campbellock Jr.” Pope, Bill “Slim the Robot” Williams, Toni Basil, and Fred “Rerun” Berry.

Pat Davis.

Damita Jo Freeman in 1974.

Adolfo “Shabba Doo” Quinones (right) down the Soul Train Line.

The Lockers.

FRED BERRY WAS MOST RENOWNED FOR HIS ROLE AS RERUN ON THE TELEVISION HIT SHOW WHAT’S HAPPENING!!, WHERE HE’D SPONTANEOUSLY BUST OUT HIS BRAND OF LOCKING IN MOST ANY PLACE, FROM THE SCHOOL CAFÉ TO THE SODA SHOP.

Don dancing down the Line with Mary Wilson in Episode 60 on May 12, 1973.

Pam Brown (center) managed the dancers with kid gloves but adult rules.

Pam Brown’s (center) tenure at Soul Train lasted as long as Don’s.

The search began at a playground in Dinker Park in Los Angeles, and all the killer dancers were there. The kids had to be at least fifteen-years-old to participate, and they came in droves for a shot to blow the minds of anyone who would admire their taut bodies, chiseled facial features, artful hair, and courageous moves. The early auditions were cloaked in midwestern naïveté—Don described them as an introduction to beautiful people who were “just plain exciting to look at.” He said that where he came from, the people who wanted to be on television should never be on television, but “LA contained every person in the world who wanted to be on television and should be.” The glamour, invention, and creativity were refreshing and made him hopeful. That first wave of auditions knocked the producers out and gave Don the gift of developing the nucleus of his show.

At the same time, Don was offering the dancers something positive to engage in, and for many it was the first time they’d get “off the block” and meet new people. The vibe of the show was to encourage the dancers to be creative while requiring them to be responsible and accountable. Don stressed that how they dressed, spoke, acted, and looked would be the face of Afrocentricity that white America would see and judge, and that being a Soul Train Dancer meant being on the frontlines of it all. Therefore Don had rules. Rule number one: Follow the rules. Others included:

• No one under fifteen could audition for the show.

• No cussing, no negativity, no perverseness in dance or language, no disrespect, no attitude.

• No gym shoes, don’t look sloppy.

• Be on time, be tactful, be creative, be funky, be yourself.

• Put your best foot forward.

• Have fun.

Don designated Pam Brown to manage the dancers, and she did just that for the entire thirty-five-year run of Soul Train, from 1971 to 2006. Her first day was the same as Don’s first day. Pam was known as “that gum lady” because she thought nothing was less attractive than a kid on television chewing gum. Her no-gum rule became the most stringent rule of all. She worked at Dinker Park full time in addition to managing the dancers. She cared a lot about those kids and knew many of them, their temperaments, even where they lived. She would give a lift to the kids who might have missed the bus back to the train station. The parents knew that when their teenagers were on the set of Soul Train or with Pam, they were staying out of trouble.

The dancers quickly became mini-celebrities. They performed at public parks, were highlighted in school newspapers, and ventured into different neighborhoods to see what else was out in the world. As we watched them from our couches in Atlanta, Detroit, Philly, wherever, we got to venture outside our own bubbles, if only for an hour. In the dancers and the Scramble Board contestants, we met people from all over, with different ways of saying things, with dance moves unlike anything we’d seen. Instead of comparing and contrasting, or rivaling, we aimed to learn something from one another, whether a hair style, a favorite song, or what other kids did for kicks. Mostly we got to learn new dances.

The way it was before technology connected the world, you would go to Detroit and people would be dancing and talking one way, and then hit Chicago and see them do things that blew your mind, and then experience totally different flavors in Mobile, St. Louis, Miami, or New Orleans. When Soul Train became syndicated, people no longer danced in different ways in different regions—they danced like the kids on Soul Train.

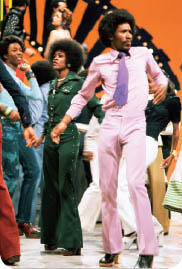

Choreographed moves and clothing were ubiquitous on Soul Train.

Pulling stunts like the performer, Mr. X didn’t need a name to be remembered.

The original superfly, Mr. X.

The Soul Train Scramble Board.

Sharon Moore makes a classic hip-bump move down the Line.

Soul Train Dancers were responsible for many iconic dance trends. Do you remember the first time your classmate did the Robot? He can thank Charles “Robot” Washington for that one. The Stop and Go by Damita Jo? And remember the Hustle, the Bump, the Bus Stop, the Backslide, the Reject, waacking, punking, tutting, popping? The Running Man? They might not have been invented on Soul Train, but Soul Train served as the vehicle to transform local, ingenious dance pioneers into decade-defining, international ones.

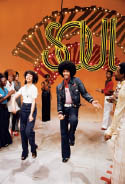

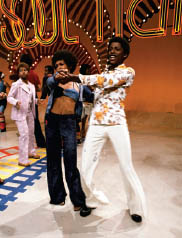

The Soul Train Line

Don said at first he resented the accusation that Soul Train was a second-rate American Bandstand, but once he really thought about it, that is exactly what it was. Except Soul Train was no sock hop. Don was clear that his dancers didn’t get in just because they waited in line; they were chosen by Pam Brown because each possessed a talent and a look that the show encapsulated. This precision in getting the right people to dance on the show was partly rooted in Don’s innate dancing ability. In Chicago’s South Side, where Don grew up, a person’s degree of coolness was wrapped up in how well he could dance. Wherever there was a party, Don was the one who would throw down, so it made sense that he brought this unbridled cool factor to televisions everywhere.

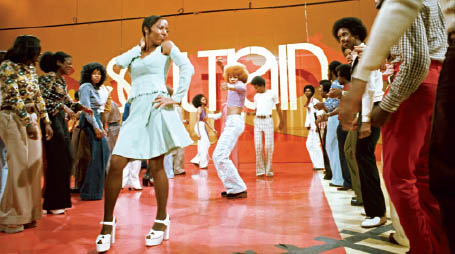

Don took the universally recognizable format of performance and dance in American Bandstand and added a whole new dimension with the Soul Train Line. Week after week everyone waited for the dancers to form the Line. You could sense them chomping at the bit, because soon it would be their turn to show how cool, how smooth, how unique, and how joyful they were.

Originally the Soul Train Line consisted of couples moving down the middle of a row of women and men, who parted like the Red Sea to witness the couple’s choreographed synchronized moves and crazy coordinated fashions. Later, two Soul Train Lines were used, one for women and the other for men. This allowed for more room to dance and more focus on the dancer and his or her individuality.

For a brief time the Soul Train Line was featured in the first half of the show. But its instantaneous popularity prompted Don to use it as the penultimate segment of the hour, before the headliner’s second song. Any broadcasting person knows that to keep viewers tuned in, there needs to be the promise of a grand finale. At my grandmother’s house where my aunts and cousins were participating in their weekly family ritual of having their hair done, the Soul Train Line was their Ice Cream Man. My job was to scream down the staircase to Grandma’s kitchen, “The Soul Train Line is next!”

The Soul Train Line only lasted the length of one song (about three minutes), but in that time, Don brought you a diverse world on its feet. And what that did was abolish the regionalism of ghetto America. Back then the country was much bigger than it is now. Whatever was happening on one side of the country, the other side would never know about. For instance, there was a way of life in the Northeast, its own style, lingo, and dance that other parts of the country weren’t privy to. The same went for the Southeast and the Midwest. Each region spoke funny and looked funnier from coast to coast, but Soul Train bridged these gaps. Watching Soul Train inspired teens to move to LA to be on the show and display their slice of life. Dance and fashion amalgamated, and black people, regardless of location, began to think on one wavelength.

The Soul Train Line was prime real estate, and dancers knew how to work the moment, no matter how brief it was.

Joe Tex and Damita Jo put on a show like no other.

Spotlight on Damita Jo

When Joe Tex pulled Damita Jo Freeman onstage exclaiming “I Gotcha” while performing the 1971 hit in Episode 27 on April 1, 1972, a star was born. She brought the song to life by dancing as if she were a mime—strumming her raised thigh like a guitar, moving her body mechanically as if she were a robot, and air kissing, teasing, and taunting Tex through strut-like movements. It was theater. Later, in Episode 176 on February 28, 1976, when Joe performed the same song, Damita Jo was part of the act, already on stage, choreographing microphone stand tosses back and forth with Tex.

Her range was fluid, mechanical, rigid, and graceful, all in one. Because she didn’t wear crazy outfits or have some sort of gimmick, her dancing and authenticity shined. She didn’t need a stage name, a hat, or a prop to do her thing.

Damita Jo invented dance moves with her partner, Jimmy “Scoo B Doo” Foster, including the Stop and Go, which she premiered in 1972 to “Slow Motion” by Johnny Williams. And when she jumped onstage with James Brown in Episode 49 on February 10, 1973, she worked “Super Bad” as if she had been on the professional circuit for years. You could see the Godfather of Soul turning to his band mates with an inquisitive look, asking, “Did you guys catch that?” Not once did he sing to the audience. He kept his eyes on Damita Jo, marveling at what she could do.

The camera was drawn to her as well, and she always found her way into the dance contest, winning the second year’s contest. What is telling about the “sweet disposition” that Damita Jo was said to have was her gutsy leadership of fellow dancers. She fought for dancers’ rights, and ultimately formed a small dancers’ union to protect them.

That a young girl with no prior background in show business was performing on a nationally syndicated show with legends like James Brown and Joe Tex was astonishing. These were precisely the sort of life-changing opportunities and messages that Don and Soul Train offered an entire generation.

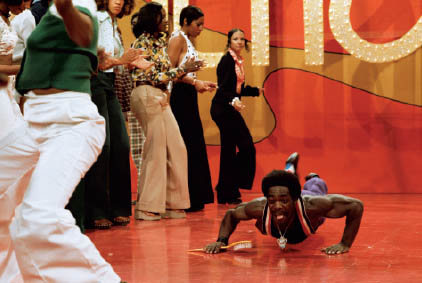

High Energy

The dancers set the tone, the mood, and the energy level of every show. Their enthusiasm for a guest and their reaction to a song, even how hard they danced, influenced how people felt on the other side of the TV. The dancers’ reaction to the music could so powerfully influence viewers’ opinions that I believe Don played less popular songs during the Soul Train Line to garner more support for them. This seemed most apparent to me as I rewatched Episode 12 on December 18, 1971, when the fun really began.

On Episode 12, Don’s pals from Chicago, the Chi-Lites, Joe Tex, and the Originals were guests. It wasn’t the performances of the three Soul Train staple acts that made the episode historical; it was the crowd that day. The studio seemed at fuller capacity than usual, and the audience truly became part of the show. The dancers were hootin’ and hollerin’, cheering on one another, and connecting each corner of the studio in a symbiotic rhythm that was a sight to see. There was so much energy that three Soul Train Lines organically formed. The dancers looked more like a community than a bunch of kids who wanted to dance to some grooves—at least that’s how it looked from my seat. I felt more like a participant than a spectator, and that is ultimately what kept everyone coming back for more.

Without VCRs and DVRs, we didn’t dare blink while the Soul Train Line segment was on, for fear of missing the moves.

As the camera panned, each dancer knew it was their time to shine.

From Street to Saturday Night Fever

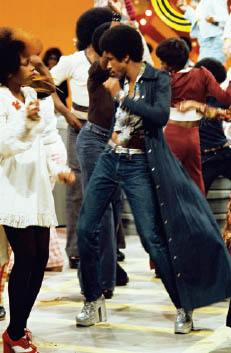

In the process of revolutionizing the art of dance on television, Soul Train introduced a pioneering form of street dance. By Episode 26 on March 25, 1972, the Lockers had come into their own, and suddenly everybody wanted to lock. The original Lockers went on to enjoy outrageous success as choreographers, actors, singers, businesspeople, and creative consultants to music’s A-list.

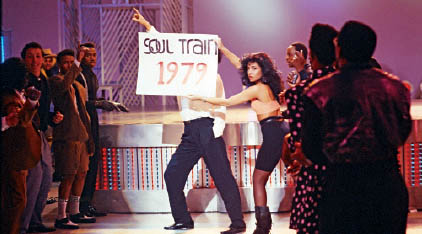

By 1977, disco had a stronghold on the country, so Don tried to adapt by inviting professional dancers on the show, including Lester Wilson and Michael Peters. Don also added dance-offs: having the dancers vote on which couple’s routine was “finished.” This was meant to quench the audience’s thirst for the disco-style, partner-centric dancing popularized by Saturday Night Fever’s Tony Manero in 1977. In my opinion, one of the most successful Soul Train shows of this period was the Minnie Riperton memorial in Episode 303 on September 15, 1979, in which a professional dance couple danced in her honor to her song “Simple Things.”

“Fluky Luke” Williamson with the Lockers.

Christina Sanchez marks the moment with her makeshift sign.

Stepping Out of Line

Before the homogenization of dance that happened during 1983, we had the pioneers of the Soul Train Line. Here are my top picks for the 1970s.

Wayne “Crescendo” Ward—Like so many of the Kids, Wayne didn’t know what he wanted to do, but upon seeing the Kids dancing on Soul Train, he said, “That’s it! That’s what I want to do!” He credits Soul Train with saving him from gangs: “Thug, hood, homeless, whatever, they watched Soul Train, so if I met up with the Four Corner Hustlers, they recognized me from the show and actually gave me money to take a cab back to my neighborhood.”

The Soul Train Dance Contest in 1975 brought out the ingenious in contestants. Even little kids had their chance to get their game on.

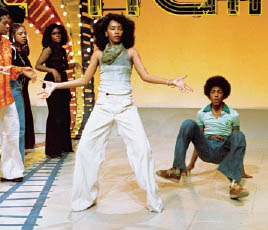

Patricia Davis—One could say Pat shares the title of First Lady of Soul Train with Damita Jo Freeman, even though Pat was officially voted “Soul Train’s Original All-Time Diva” by her peers at a dancer reunion. The camera panned the studio in search of her as much as it did for Damita Jo. While other dancers smiled and mouthed the lyrics to the songs they were moving to, Pat had a stoic look, one of intense focus that said, “I’m in the business of dancing.” She often dressed her hair in oversized, colorful flowers and butterfly clips, inspired by Billie Holiday. Pat was breathtaking to watch down the Soul Train Line—as a rag doll, in a man-tailored suit, or as her showstopper self. She was the epitome of what black girls strived to be: oozing with soul. Oh, and she got to wipe the sweat off Marvin Gaye’s forehead during “Let’s Get It On.”

Even Michael Jackson got a lot of his moves from watching Soul Train. There were not many places that Michael Jackson could go to get ideas about dancing.

IKE TURNER’S COUSIN QUEEN TURNER WAS A SOUL TRAIN DANCER, WHOSE PARTNER WAS EDDIE FRANKLIN, ARETHA FRANKLIN’S SON.

Jimmy “Scoo B Doo” Foster—You had to feel bad for any dancer who went down the line with Scoo B, because you hardly noticed her, unless it was his legendary partner, Damita Jo, who was responsible for bringing him on the show. He was that good and intensely fun to watch. Already a member of the Lockers before joining the show, Scoo B was a master at making his long limbs extend even farther, like an X marking the spot across your TV set. He invented a slew of dances, including the Scoo B Doo, the Scoo-Bot, the Stop and Go, the Scoo B Hop, the Scoo B Kick, and the Scoo B Walk. And if his fluid movements and magnetic personality didn’t make your lashes stick to your eyebrows, his rubber band–like jumps and splits and his sole-sliding manipulations would.

Thelma Davis—Thelma was one of the original members of the Soul Train Gang. Her dance style wasn’t as flashy or flamboyant as that of some of the other dancers. Instead it was elegant and had a flair of trained control, as she spun with precision or danced ballroom style with her many partners. Thelma referred to herself as the “pass around girl” on the dance floor because she got bored easily. When a partner wanted to do the same routines and steps over and over again, she would move on to someone else, wanting to try something new. Dressed many times in a leotard, she looked like she was heading to a ballet bar right after the show.

Darnell Williams—Darnell, who hailed from London, gained fame after Soul Train starting in 1981 for his role as Jesse Hubbard on All My Children. (Before you get the wrong idea, take heart in the fact that my parents were still on their PBS kick then, so my fandom remained strictly related to his role on Soul Train.) He won Daytime Emmy Awards for that role.

Tyrone “The Bone” Proctor and Sharon Hill—Sharon was one of the prettiest and most energetic dancers to grace Soul Train. After Pat Davis urged Sharon to find herself a partner, she saw Tyrone practicing his moves and asked him to join her. So they got together and were asked to do a routine for the weekly dance contest. She and Tyrone did the P.A. Slaughter, which got them into the Los Angeles finals of the Soul Train dance contest. Their routines won each of them many fans across the country, and they became one of the show’s most popular couples. They even won a dance contest on American Bandstand.

SHARON MET HER HUSBAND, MARK WOOD OF THE R&B/FUNK GROUP LAKESIDE, THROUGH SOUL TRAIN.

We tuned into Soul Train so we could show off our moves at parties. It’s hard to imagine a world without Soul Train to provide an outlet for dancers like these.

Lil’ Joe Chism and Yolanda Seay—Lil’ Joe and Yolanda were regular dance partners who did the Scramble Board and won a year’s supply of Ultra Sheen and Afro Sheen products. Yolanda was a vibrant and terrific dancer as well as a fashionista. She smiled a lot, attracting viewers to her warm girl-next-door persona. Lil’ Joe was known for smuggling dancers, including Jeffrey Daniel, into the studio, even though they were supposed to wait in line. I remember thinking Lil’ Joe and Yolanda had to be nervous when they competed in the Soul Train Dance Contest, which was judged by Don and James Brown. However, Yolanda basically went down in lucky-girl history when Marvin Gaye sang “Let’s Get It On.” He pulled Yolanda out of the crowd and sang to her, and afterward she gave him a little kiss on the cheek.

Jermaine Stewart—Pal of Jeffrey and Jody on the dance floor, Jermaine was originally up for lead singer of the group Shalamar, but lost the part to Howard Hewett. Jermaine did, however, tour with the group and remained close with his fellow Chicagoan childhood friends in it, Jeffrey Daniel and Jody Watley. Later, Culture Club member Mikey Craig assisted Jermaine in making a demo and invited him to sing backup with the band until they helped him get a contract with Arista. The result: “You Don’t Have to Take Your Clothes Off.”

PATTI IS ONE OF A SELECT GROUP OF ARTISTS WHO ALWAYS INSISTED ON SINGING LIVE. WITH NINETEEN-PLUS PERFORMANCES, SHE HOLDS THE RECORD FOR HAVING HAD THE MOST LIVE PERFORMANCES OF ANY ACT IN THE SHOW’S HISTORY. OTHER LIVE PERFORMANCES INCLUDED ONES BY BARRY WHITE, AL GREEN, JAMES BROWN, THE J.B.’S, SLY & THE FAMILY STONE, AND TOWER OF POWER.

Labelle never failed to show up in the craziest ensembles.

Labelle in Episode 118 on December 7, 1974.

Side Effect.

Focus on Fashion

Black artists discovered that it wasn’t enough to perform material—they had to entertain their audiences. Visual presentation in a live setting proved crucial to those who would thrive in the 1970s and into the future. The London fashion scene had influenced the style of the 1960s in America, specifically the Bay Area. David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust persona proved mightily influential to both rock and soul audiences, giving them a limitless palette to work with. In my opinion, Labelle’s Episode 118 on December 7, 1974, marked the beginning of a wave of outlandish futuristic costumes. Even though the Pointer Sisters also used theatrics, their references were to an older time. Labelle used costume and theater to reflect the unknown future.

Labelle came to perform their most popular hit, “Lady Marmalade,” sung by Patti LaBelle. Labelle’s performance elicited some of the loudest outbursts of excitement and praise, which during this period of Soul Train was quite the achievement, since the standards were already so high. In her nine appearances on the show, Patti never left the Soul Train audience underwhelmed.

Soon other bands stepped up their presentation game. Mandrill, the New Birth, Instant Funk, Jeffrey Daniel, the Trammps, Side Effect, Teddy Pendergrass, and Shalamar, among others, would baffle, humor, and sometimes haunt me.

Jody Watley and Jeffrey Daniel were childhood friends and dance partners on Soul Train.

Spotlight on Jeffrey and Jody

Probably the most famous dancers to come out of the show, Jeffrey Daniel and Jody Watley were proof of what happens when talent merges with opportunity. They were friends from church from the time Jody was a young teen. A young Jeffrey and Jody carpooled to Soul Train to dance their hearts out. They were accompanied by fellow Chicagoan and Soul Train dancer Jermaine Stewart.

Once Jeffrey and Jody achieved a notoriety and fan base, they began incorporating skits into their dances. A personal favorite of mine is Episode 197 on November 13, 1976 (Aretha Franklin and Ronnie Dyson), where they staged a faux brawl. I thought this was a stroke of genius and moments like these constantly kept me tuned to see what antics they would pull off next. Nobody expected it, and everyone thought it was real, even fellow dancer Tyrone Proctor, who broke up the fight by pulling them apart.

By Season 6 in 1976, the lack of set design and distractions allowed the power couple to shine even more. They began using different props, inciting the popular uses of Chinese fans, skateboards, pogo sticks, a unicycle, and umbrellas. They dressed in running gear, did aerobics, rolled on the ground—you name it.

Of course, what else would you expect from the guy who essentially taught Michael Jackson how to moonwalk, and the woman who would go on to become a Grammy Award–winning solo artist? How about joining a musical group, calling themselves Shalamar, and selling millions of albums worldwide over a seven-year period?

Diana Ross makes a special guest appearance in Episode 55 on April 7, 1973.