THE BIG MOMENTS

For me, the interviews between Don and his guests always let the genius out of the bottle. He used the interview segments for a variety of purposes. There were those fashioned as public service announcements, like when Stevie Wonder spoke about the importance of education or James Brown explained that black-on-black crime could not be tolerated. There was also flirty Don, who couldn’t hide his crushes on female artists, including Bonnie Pointer. Every time Bonnie was in close proximity, even the eight-year-old me knew to yell at my television set, “Get a room.” At other times, Don would run the risk of inciting sibling ire by giving a little too much attention to Bunny DeBarge or Joni Sledge. Even in the hottest moments, Don was so suave that he never lost his cool, no matter who the guest was. The one exception was Diana Ross; he admitted that she made him nervous. And even that admission represented its own kind of humanizing cool.

Diana Ross had already broken from the Supremes by the time she met Don on the set of Soul Train.

After the Rumble in the Jungle match, George Foreman comes in peace to Soul Train in 1974.

Billy Davis Jr. and Marilyn McCoo of the 5th Dimension talk with Don in Episode 87 on January 26, 1974.

In my opinion, Soul Train would have enjoyed only a five-to seven-year run had it not been for Don’s professionalism and ability to communicate through the interviews. Having been on the show twice myself, I can attest that he was the epitome of coolness. The Roots’ first episode, number 946, aired on March 4, 2000. Shemar Moore was hosting, since Don had retired from that side of the show six years before. But Don was still there writing, directing, and producing, and I heard him bragging, “I didn’t have cue cards in my day.” This completely shocked me. How did he absorb all that text? Simple, he didn’t. He genuinely loved his baby and the artists who came to nurture it, so he exuded an air of absolute confidence. And he did his own research, another rarity in show business.

During some interviews, you met a side of Don you couldn’t believe existed. I call it “locker room” Don. It was that guy’s guy thing, and he only had it with certain people. Seeing the fatherly, authoritative Don let loose and talk straight up to a guest as if they had just finished a game of pickup, forgetting the audience was there, was such a kick. That’s why there was always an extra bonus whenever the show was visited by the Whispers, the Temptations, and especially the O’Jays. Don was the loosest during one of the most treasured moments—the famous basketball game between Don and Marvin Gaye, refereed by Smokey Robinson, on TOP 10 ALERT EPISODE 222 ON MAY 7, 1977. For me, this was one of the only good things that happened during Soul Train’s disco era.

Cholly Atkins working with the O’Jays on their song “Give the People What They Want.”

Watching these segments now is so entertaining because I catch sexual innuendos, professional business tensions, and mutual respect that were lost on me as a child. For instance, minutes before the Supremes’ Mary Wilson convinced Don to accompany her down the Soul Train Line in TOP 10 ALERT EPISODE 60 ON MAY 12, 1973, she asked him, “Don, can I dance with you?” Don replied, “Yes, but not on television.” After a commercial break, the Soul Train line segment began, and toward the middle of the song, Don and Mary danced down the Line to “Doing It to Death” aka “Gonna Have a Funky Good Time” by the J.B.’s. This is a top ten alert, as it marks the only time Don danced down the Line. He certainly lived up to his South Side reputation. These were the moments that made everyone smile and feel like they were being invited into Don’s world in a big way.

The O’Jays

The O’Jays’ performances were consistently solid and crowd-pleasing. Their every appearance caused a frenzy among the female dancers because of Eddie Levert’s emotive singing style. The personal chemistry that Don and Eddie shared brought a humorous backdrop to the show. And as incredible as the O’Jays performed, the banter between the two was the true highlight. Eddie helped bring out Don’s humorous side, which was so integral to his persona.

Humor is a way to gain access to the third dimension of a stranger. With humor you get to see someone’s vulnerable side because humor helps people relax. Don and Eddie’s relationship was particularly notable because it was like watching two old friends talk and have fun on camera in front of millions of people. They would often “play the dozens,” meaning they’d dig on one another, joking about a hit single or lack thereof, how one of them was too old, or not hip. In Episode 57 on April 21, 1973, Don invited Eddie to do an impersonation of him, one which Eddie had first showed off at a party they both attended in Cleveland.

For me, a big moment was when the O’Jays enlisted the talents of the incomparable Cholly Atkins, known for his choreography of the Motown family. From the Supremes and the Four Tops to the Temptations, Cholly basically taught them how to dance, spending countless hours rehearsing. He helped define the Motown brand, as each act’s package relied on choreography. Atkins also stepped outside the Motown circle and choreographed many other groups of the ’60s era.

In the mid-’70s, the world of television had few frills, so even the slightest editing trick was enough to make my jaw drop. In Episode 153 on October 11, 1975, a behind-the-scenes tape aired showing Atkins working with the O’Jays on choreography for their song “Give the People What They Want.” Cholly was counting the cadence, “1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4,” as the guys turned and stumbled over their feet. “Do it like you were on Soul Train,” Cholly challenged them; and bam, the O’Jays were cleverly transformed into their show clothes and onto the Soul Train set, where they rolled right into the song, sans the typical introduction by Don. This raw look at what went into getting from point A (conception) to point B (polished and poised entertainers) added an entirely new dimension to what music, entertainment, and collaboration were all about. It showed how Soul Train continued to creatively strive to set new standards in television production and avoid becoming stale while giving the people what they wanted (before they knew they wanted it).

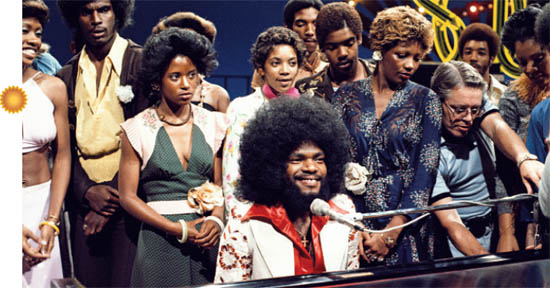

Billy Preston is magnetic in Episode 85 on January 5, 1974.

There’s something to be said about a backstage glimpse of the blood, sweat, and tears that musicianship and entertainment require. But what makes TOP 10 ALERT EPISODE 314 ON DECEMBER 1, 1979, easily an iconic top ten moment of Soul Train, and perhaps in all of performance history, is the exact opposite. In a “Salute to Aretha Franklin,” when Don facetiously challenged a young, pristine Aretha on whether she was “even old enough to know any of Smokey’s music,” she didn’t flinch. Smokey’s cackling reaction had that boys’ club flavor I enjoyed so much between Don and his guests. A jab at the “old man” Smokey it was not. Sitting to the left on the piano bench next to her Detroit comrade Smokey, Aretha was expressionless until she bore the weight of her fingers onto the ivory keys and prayerfully cooed, “Ooo, baby baby.”

Effortless. It was the exact opposite of the commendable rehearsing I’d seen Cholly Atkins do with the O’Jays. It was obviously the other side of the same talent coin. Aretha continued, “Ooo, baby baby.” Like a cat to nip, Smokey rang in his falsetto, and they hypnotically fell into a melodious duet as if they had done it a million times. It was raw organic talent that needed no choreography or showmanship. The stuff legends are made of.

A duo worth dying for, Aretha and Smokey sing it out in Episode 314.

The Fifth Beatle

Similar to Ike and Tina, Billy Preston wasn’t deemed a soul act just because of the color of his skin. He was rock ’n’ roll royalty and had more white fans than black. But Billy, gospel born and soul bred in his bones, arrived to Soul Train acknowledging that he was one of our own. He was not your average piano-playing, singing guy; and Don made certain to say so, establishing for his viewership that this man was a legend, “the fifth Beatle.” I was proud of Don for the reverence with which he treated Billy.

The Isley Brothers

I honor Chuck Berry and Little Richard as the father and architect, respectively, of rock ’n’ roll, but I will say that the Isley Brothers on Episode 119 on December 14, 1974, had an almost hypnotic effect on the Soul Train Kids. This was most notably because of the youngest brother, Ernie Isley, who spent his childhood hiding in a closet spying on frequent stowaway and unofficial family member James Marshall Hendrix as he practiced his left-handed guitar.

After the army honorably discharged him for “unsuitability” in 1962, Jimi Hendrix cut his teeth in the R&B grind doing stints with Little Richard. The last group he worked with before he became Jimi Hendrix was the Isley Brothers. They took him into their New Jersey home from the streets of Greenwich Village. While he was practicing his skills, Ernie was eleven or twelve years old, and he observed Jimi’s every move and then practiced what he saw. And quiet as it is kept, the baton was passed to Ernie when Jimi passed in 1970.

People often think that Jimi’s music found its way into George Clinton’s P-Funk universe, but I don’t think any group had its feet planted in traditional R&B’s past and psychedelic rock’s future better than the Isley Brothers. And this episode demonstrates it well: they are live, and they are loud. The band let Ernie take over the show, picking up where Jimi left off—playing with his teeth, lying on his back on the floor. For a black America that, like me, didn’t know any better, he looked like the pioneer of this stuff. The episode is one of my personal favorites because I had never seen showmanship like this in my life. It is also a historical pick because it established that the Isleys would experience a third decade of success. They grew from a doo-wop act into a futuristic funk rock hybrid. It was a reinvention that most acts could only dream of.

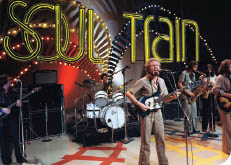

Average White Band and the Undisputed Truth

Episode 161 on December 6, 1975, featured Average White Band and the Undisputed Truth. This is the first time that the Soul Train audience got to see a white band transposed in a black tradition. Even Don’s introduction noted the novelty of Average White Band: “Here is an act that must be seen to be believed. A group so funky you’d swear that they were raised on collard greens, black-eyed peas, and ham hocks, even though they were raised in the UK.”

This was when I stopped trying to be a Bill Withers wannabe guitarist and decided to become a Steve Ferrone–like drummer. Average White Band played live on the show, and instantly I said to myself, That’s my instrument. It was important for them to play live, because without the use of video, America would not have believed who was making a sound so authentically black. Steve, who had just joined the band, was the only African American member. Everyone had seen white acts redo rock ’n’ roll and doo-wop, and play jazz and Bach, but to approximate funk was probably the blackest expression a performer could make.

The Undisputed Truth in Episode 161 on December 6, 1975.

The Isley Brothers in Episode 119 on December 14, 1974.

There’s nothing average about Average White Band in Episode 161 on December 6, 1975.

Add to this episode the second appearance by the Undisputed Truth, a band pigeonholed as a gender-mixed group like the 5th Dimension and Hues Corporation, which were not as popular as unisex groups like the Temptations or the Supremes. At the time, they didn’t stand out as much as those groups, despite their ’70s hit “Smiling Faces.” On the Soul Train stage, though, they came out wearing silver makeup, white wigs, and platform shoes—a crazy cosmic motif. Along with the New York Dolls, David Bowie, and Funkadelic, their outer space shtick proved to be a reinvention for the ages. I remember Don’s reaction during the interview: he was a little weirded out. I think this was because they had looked so normal in Episode 16 three years earlier.

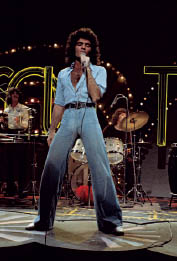

Gino Vannelli, a Canadian signed to the A&M label, stood out for being the first white vocalist on Soul Train in Episode 128 on February 15, 1975. His style was jazz and progressive rock, closer to the music of Weather Report than James Brown.

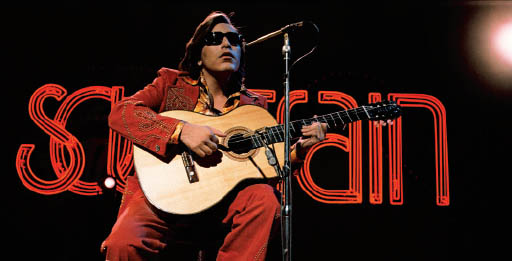

José Feliciano in Episode 120 on December 21, 1974.

Trifecta

Episode 120 on December 21, 1974, showcased a headliner, a supporting act, and a guest act that each hit the bull’s-eye—José Feliciano, Minnie Riperton, and the Dynamic Superiors.

In the first act of this rare trifecta, Feliciano’s singing was on fire, which was important for indicating how people from other cultures embraced the show. The Puerto Rican singer from Spanish Harlem stunned the audience with a fiery performance of “Hard Times in el Barrio,” a cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Golden Lady,” and a striking version of “California Dreamin’” by the Mamas & the Papas.

Not to be outdone, Minnie, in her five-and-a-half-octave glory, demonstrated her dexterity with “Lovin’ You” and “Reasons,” as if they were walks in the park. I remember her performances because she looked just like she does on her album cover, and at the very end of “Reasons” she replicated the sound of a chirping bird. Mortals would have to whistle to reach that high a note, and when Don asked her if she had a golden larynx, Minnie shrugged it off. I had never heard a human being sing that high before, so to watch someone sing notes that you had thought up to that point were whistles was thrilling.

The third act, the Dynamic Superiors from Washington, DC, put on one of the finest near Baryshnikov-level choreographed performances I’ve ever seen, with “Shoe Shoe Shine.” You would think there isn’t much you could do with such a slow melody, but the precision required to keep pace with the ballad is precisely what made the choreography complex. Their moves were exacting and in sync, as they used up most of the floor space to showcase their blend of tapping soles and sweeping footwork.

HISTORIANS NOTE THAT THEY COULD HEAR THE SOUNDS OF MINNIE RIPERTON’;S THEN TWO–YEAR–OLD DAUGHTER, MAYA RUDOLPH, OFF STAGE.

Minnie Riperton in Episode 120 on December 21, 1974.

In July 1979, Minnie Riperton passed away from breast cancer. I was eight years old, and yet the gravitas of the moment was clear. The “Tribute to Minnie Riperton,” in Episode 303 on September 18 of that year, made me sad. I was used to Soul Train being a jovial, celebratory environment, and the dimly lit set made it clear that this was an occasion for mourning. The highlight was an unannounced performance by Stevie Wonder. And even his demeanor was a little too somber. Stevie’s previous performances had shared the motif of him sitting next to Don at the piano, singing impromptu songs. That wasn’t the case this time. Stevie revealed, even though most suspected, that he was the producer of Minnie’s Perfect Angel album. The album credits include “El Toro Negro” (The Black Bull). Everyone knew Stevie is a Taurus and black.

On the episode, Don and Stevie spoke softly to one another. Don said, “You wrote and produced this record.” “Yeah, I was there. I helped,” replied Stevie, his voice cracking. He told stories of how he was obsessed with Minnie, how he had been a fan of her previous group, Rotary Connection, and how when he first met her, he begged her to let him produce her music. It was a sad moment, and as I watched with my grandfather and cousin, I felt the historical significance.

Minnie Riperton.

The recurring theme for the top ten moments on Soul Train is, for the most part, that they were spontaneous moments. When it comes to off-the-top-of-the-head, freestyle wizards, B. B. King, Bobby Bland, and James Brown occupy that street. Is there any form of music that embodies the spirit of visceral impromptu music better than the blues? TOP 10 ALERT EPISODE 132 ON MARCH 15, 1975, was another one of those teachable moments, where you saw all three trading off-the-cuff lyrics like well-seasoned jazz musicians. Don’s nod to the blues legends was an act of commemorating the African American culture, humbling us all with the reality check that even on the eve of the hedonistic disco era, the need to sing the blues might never be too far away.

B. B. King (left), James Brown (middle), and Bobby Bland (right).

Elton John in Episode 121 on May 17, 1975.

Elton John

When Elton John appeared in Episode 141 on May 17, 1975, the show reached its summit, both visually and culturally. His outfit made him look like the leprechaun in my Lucky Charms morning cereal, and his appearance underscored the feverish reputation Soul Train had achieved. By this time, established pop stars like Elton were vying to get on the show. Elton had told Don that he was a fan, using the unfortunate phrase of being “amused by the show.” Nonetheless, when Elton’s people reached out to Soul Train for a booking, Don rolled out the red carpet.

By 1974, Elton had enjoyed two years of massive fame in the States after he hit the Billboard chart with “Rocket Man (I Think It’s Going to Be a Long Long Time),” “Crocodile Rock,” and “Daniel,” and reached glam rock status after his Goodbye Yellow Brick Road album gave the world several more hits. Elton’s arrival was a spectacle, and Don went to the ends of the earth to ensure it was nothing short of spectacular. Only certain dancers were allowed to be on the show, and Elton was permitted to sing live and bring along his custom plexiglass piano.

Performing “Bennie and the Jets” and “Philadelphia Freedom” in his glorious glittered eyewear, Elton was a natural fit—an English pop sensation with soulful overtones. The dancers reacted to Elton by mouthing and singing along. The episode was an important moment for cultural relations. It stated to me that if your music was quality, you would be embraced by Soul Train. Talent transcends all, no matter what color you are. Elton was a prime example.

David Bowie

Botched lip-syncing aside, I loved Bowie’s performances of “Golden Years” and “Fame” in Episode 165 on January 3, 1976. Funky and cool, both songs were well received by the Kids, and Bowie’s grooves coupled with his superlative persona and quality sense of humor called attention to the elephant in the room—that it was impossible to lip-sync songs with special effects like the ones in “Fame.” So what did the guy do? Well, near the end of his song, he stopped and stood staring at the microphone. Then he flicked it as if to say, “Is this thing on?”

Don introduced him as “one of the world’s most popular and important music personalities,” and began the interview. Bowie plugged his film The Man Who Fell to Earth, as well as his upcoming world tour, and told Don that he hoped Russia would allow him to play there. Bowie was nothing but gracious and enthusiastic to be on the show, and the audience members seconded a congratulatory comment made by one of the Kids during the Q&A segment, applauding him for “getting into soul music.” To me, he looked surprised, as though he hadn’t thought of it like that. The Kids and Don accepted Bowie because he was the real deal—a multifaceted star from across the pond. His music was just plain good. Surpassing color, gender, age, genre, and hometown, talent and the sound of one’s music is what really matters.

The End of the Decade

An entire decade had been defined by an intrepid man with a novel idea, but that is not to say Soul Train didn’t equally benefit from what the decade had to offer it. A perfect give-and-take that was at the right place at the right time, Soul Train in the 1970s answered a community’s search for a rainbow behind a hovering dark cloud of grief, loss, and hopelessness. It took a man who was in love with dancing and music to bring a celebration of Afrocentricity into everyone’s living rooms. In a short amount of time, a show that couldn’t attract the “big acts” was not only turning down the soul royalty of the ’50s and ’60s as well as the current trendsetters of the ’70s, it went on to discover and nurture its own acts.

An empire had been built in what seemed like a day, and now it was time to say goodbye to free-bird dance grooves, overgrown Afros, chitlin circuits, five-man Motown singers, and supergroup sensations. Throughout the early ’80s, familiar faces still dropped by the Soul Train stage, but eventually a new era took over that would transform Don Cornelius’s dream and take it to a whole new level.

With a decade behind him and many top ten moments under his belt, Don certainly had something to smile about.