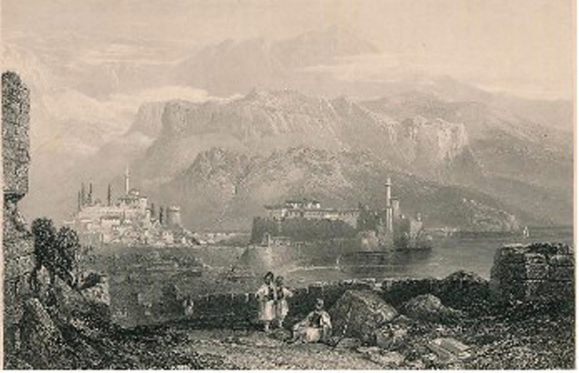

Fig. 13: Engraving by Edward Finden taken from a drawing by William Purser for The Life and Works of Lord Byron (1833).

Fig. 13: Engraving by Edward Finden taken from a drawing by William Purser for The Life and Works of Lord Byron (1833).

| The sun had sunk behind vast Tomerit,1 And Laos2 wide and fierce came roaring by; The shades of wonted night were gathering yet, When, down the steep banks winding warily, Childe Harolde saw, like meteors in the sky, The glittering minarets of Tepalen,3 Whose walls o’erlook the stream; and drawing nigh, He heard the busy hum of warrior-men Swelling the breeze that sigh’d along the lengthening glen. |

||

| LVI | He pass’d the sacred Haram’s4 silent tower, And underneath the wide o’er-arching gate Survey’d the dwelling of this chief of power, Where all around proclaim’d his high estate. Amidst no common pomp the despot sate, While busy preparation shook the court, Slaves, eunuchs, soldiers, guests, and santons5 wait; Within, a palace, and without, a fort: Here men of every clime appear to make resort. |

500 |

| LVII | Richly caparison’d, a ready row Of armed horse, and many a warlike store, Circled the wide extending court below; Above, strange groups adorn’d the corridore; And oft-times through the Area’s echoing door, Some high-capp’d Tartar spurr’d his steed away: The Turk, the Greek, the Albanian, and the Moor, Here mingled in their many-hued array, While the deep war-drum’s sound announced the close of day. |

510 |

| LXII | In marble-paved pavilion, where a spring Of living water from the centre rose, Whose bubbling did a genial freshness fling, And soft voluptuous couches breathed repose, ALI6 reclined, a man of war and woes: Yet in his lineaments ye cannot trace, While Gentleness her milder radiance throws Along that aged venerable face, The deeds that lurk beneath, and stain him with disgrace. |

550 |

| LXIII | It is not that yon hoary lengthening beard Ill suits the passions which belong to youth; Love conquers age -- so Hafiz7 hath averr’d, So sings the Teian,8 and he sings in sooth -- But crimes that scorn the tender voice of truth, Beseeming all men ill, but most the man In years, have mark’d him with a tiger’s tooth; Blood follows blood, and, through their mortal span, In bloodier acts conclude those who with blood began. |

560 |

From Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto II, published in 1812.

On the publication of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage in 1812, Byron later remarked, ‘I woke up to find myself famous’. The poem’s overnight success made the young Lord George Gordon an instant celebrity, and as a consequence of its international fame promoted the mystique of a hitherto obscure Albanian warlord, Ali Pasha. Its narrative follows the journey of a dissolute and disenchanted youth who seeks escape through exotic travel, a theme that was perfectly timed to tap into the growing Continental tastes for romanticism and Orientalism. It was not a work of pure fiction though, but an imaginative retelling of the author’s own adventures, interspersed with meditations arising from his new experiences. One such key moment, the dramatic and evocative description of Byron’s alter ego Childe Harold’s arrival at Ali’s court, gave the European reading public a tantalizing glimpse into a hidden world, and forever linked Ali with Byron both in life and the imagination. This fanciful version of the real-life, and at the time unlikely, meeting of the rising star of the Romantic Movement and a Balkan petty despot is conjured up in dreamlike language reminiscent of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, with its vivid portrayal of the Mongol emperor’s paradise palace.9 It was at Tepelene that Ali had built his own version of paradise, a lavish palace or seraglio, and it was here that Byron and his old Cambridge friend ‘Cam’ Hobhouse were invited to meet him, in 1809. Hobhouse kept his own diary of the journey and his account, with its description of Ali, was published a year later, filling out the prosaic details.10

When Byron and Hobhouse met Ali Pasha he was by then an established potentate in the Oriental fashion, and as a pasha of three tails, the highest rank, commonly given the title of vizier. Although Byron relished the notion of being a pioneer in travelling to such a remote region as Albania, and it is true that Ali’s court would be relatively inundated with Western visitors following in his footsteps, he and Hobhouse were not the first Westerners to pay Ali court. Ali’s growing clout and reputation had made him of great interest to the ‘powers’ (Britain, France, Austria and Russia) as well as of concern to the Sultan. The French had established diplomatic relations since 1797, and François Pouqueville, who would have a profound influence on French writers and politics, was their ambassador there from 1806 to 1815. Britain, concerned with this French influence, responded by making its own representations, and from 1801 onwards had formal relations. Captain William Leake was their man in Ioannina, Ali’s capital. Leake was well travelled and knowledgeable with a military man’s interest in topography and ancient history. His own meticulous accounts of his experiences, Travels in Northern Greece, were not published until 1835, by which time Ali’s name was well known. Leake’s description of Tepelene, on a bluff above the River Vjosë (Aoos) with its palace ‘one of the most romantic and delightful country-houses that can be imagined’, while accurate, would not linger in the imagination to challenge Byron. Reality and romance would be in continuous tension in the recording of all that surrounded Ali. In his diary, Hobhouse records his first impression of Tepelene as ‘ill-looking and small’.

Byron’s poetic antennae were sensitive to a different reality and alert to the making of a legend, one growing in the telling there and then. Ali’s life had already been committed to verse in the Alipashiad by his court poet, Haxhi Shehreti (Hatzi-Secharis, Hatzi-Sechris or Hadji Seret), a work Leake analysed in his Travels, and visitors were honoured in Ali’s presence with war-songs about his victories over the Suliotes. Through Byron’s eyes this inflated heroic vision of Ali, Albania and Greece became the raw material for an Oriental dream. Byron was also sympathetic to other resonances. His descriptions and meditations chimed in with universal, grass roots notions of liberty and nationalism that were taking hold all over Europe. In Britain, memories of the Jacobite Rebellions of 1715 and 1745 were still fresh. Rob Roy McGregor, whose exploits were fictionalized by Sir Walter Scott in 1817, was a prototype of the Romantic outlaw and freedom fighting folk hero. A legend too in his lifetime, he was moulded into a cultural icon of the nineteenth century. The tragically heroic defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Scottish clans at Culloden, which finally put an end to rival claimants to the British crown, only added to this myth-making. The stories around Ali, ambiguous and malleable, provided new source material for the outlaw turned hero, or tyrant turned freedom fighter, and Byron was particularly sensitive to the Romantic appeal of these contradictions.

Because of his turbulent family background Byron had spent his early childhood growing up in relatively humble circumstances in Aberdeenshire. As a Radical, he would have had little sympathy with the absolutism of the Stuart pretenders to the British throne, but he was descended on his mother’s side from King James I of Scotland, and the history of his ‘Ill starr’d, though brave’ ancestors who were ‘destined to die at Culloden’, was all around him. His poem Lachin y Gair (1807) recalls the mountains of his youth where:

my young footsteps in infancy, wander’d:

My cap was the bonnet, my cloak was the plaid;

On chieftains, long perish’d, my memory ponder’d,

As daily I strode through the pine-cover’d glade;

With such thoughts in mind he found in Albania a second home. The rugged Epirote Mountains immediately struck a chord, being ‘Caledonian, with a kinder climate’, and the independence and feuding of the Albanian families reminded him of the humbled Scottish clans. The right to wear their highland dress, the kilt, had only been restored to them six years before his birth, so when he wrote, ‘The Albanese struck me forcibly by their resemblance to the Highlanders of Scotland, in dress, figure and manner of living’, there was an added poignancy. These foreign highlanders inhabiting their ‘glens’ dressed in warlike attire that consisted of a ‘kilt’, or fustanella, recalled the lost highland glory. Even the Bristol born Hobhouse succumbed to this Caledonian nostalgia; the Gulf of Arta, reminding him of Loch Lomond. A few years later, Sir Henry Holland (from Cheshire), who went on to study medicine at Edinburgh University, also made the connection. He visited Albania between 1812 and 1813 and in his subsequent account put the size of population at less than 2 million with ‘the superficial extent of Ali Pasha’s dominions not differing greatly from that of the sister kingdom’ of Scotland.

Ali already had a ferocious reputation. Byron and Hobhouse were not totally ignorant of this before they set off for his territories, but they were young; Byron was only 21, and somewhat politically naive. They had decided to visit Ali seemingly as the result of a last-minute whim while on a stopover in Malta, a port of call on their Grand Tour. As the usual itinerary for such an enterprise was no longer available due to Napoleon’s occupation of Italy, they had taken a circuitous route via Portugal and Spain, with the intention of making for Constantinople and the Levant instead; wanderings that would provide the raw material for Childe Harold. Britain’s treaty with the Ottomans in 1799 had opened up the option of visiting the Balkans on the way, and in particular Greece, the authentic birthplace of classical civilization. Albania was a further detour.

Malta, liberated from the French in 1800, was quickly becoming key to British interests and shipping in the Mediterranean. Here they met Spyridon and George Foresti, father and son, Greeks from Zante, one of the Ionian Islands, and both in the service of the British Government. Spyridon had acquired a dashing reputation when, as Assistant to the English Consul at Zante, he had single-handedly boarded The Grand Duchess of Tuscany, shot and overpowered the pirate who had captured her and salvaged £80,000 worth of cargo. With the islands back in the hands of the French, he was now the exiled English resident in Corfu, apparently with time on his hands. Idling on Malta as yet undecided as to their next move, it was Spyridon who seems to have been largely responsible for Byron and Hobhouse visiting Albania and Ali.

Foresti showed them the sights, all the while beguiling them with stories of Ali, who was at this time friendly towards Britain. Napoleon had apparently sent Ali a snuffbox with his picture on it. Byron wrote to his mother that Ali thought ‘the snuffbox was very well, but the picture he could excuse, as he neither liked it nor the original’. Hobhouse’s diary records that Foresti told them of ‘some curious passages from the wars of the Suliotes written in Modern Greek’ in which,

Three hundred women flung themselves over a cliff. The son of the chief Suliote being taken before the son of Ali Pacha in Ioannina, the young Pacha addressed him with, ‘Well, we have got you and we will now burn you alive’ – ‘I know it,’ replied the prisoner, ‘and when my father catches you he will serve you in the same manner.’

Within six days, in late September, Byron and Hobhouse were aboard The Spider and under sail bound for Preveza, with letters of introduction to ‘Captain Leake’ at Ioannina and to Ali’s court. The exact motives and circumstances of Foresti in diverting Byron towards Ali are murky and will be examined later.

On arrival at a newly built barrack at Salora, the tiny port and custom depot of Arta, Byron was regaled by songs from the Albanian guards. One song eulogized the taking of the nearby port of Preveza from the French (and its Greek defenders), while extolling the name of Ali. Hobhouse tells us that when Ali’s name came round in a song it was dwelt on and roared out with particular energy. This event had taken place eleven years earlier, but the material found its way into Childe Harold, where Byron paraphrased the war-songs sung by the victorious dancing Suliotes:

Remember the moment when Previsa fell,

The shrieks of the conquered, the conqueror’s yell;

The roofs that we fired, and the plunder we shared,

The wealthy we slaughtered, the lovely we spared.

I talk not of mercy, I talk not of fear;

He neither must know who would serve the Vizier;

Since the days of our prophet, the crescent ne’er saw

A chief ever glorious like Ali Pasha.

These were the very same Suliotes he had heard about killing themselves rather than surrender to Ali. The song goes on to glorify Ali’s eldest son, ‘Dark Muchtar’ in Byron’s phrase, who with his horsemen was at this time distinguishing himself campaigning on the Danube against the Russians.

Thomas Hughes who travelled through Greece between 1813 and 1814 with the architect and archaeologist Charles Cockerell records in his own Travels that songs of Ali Pasha’s exploits were commonplace. As he sailed through the Gulf of Corinth toward Epirus, he was introduced to Ali in song by the sailors on his boat who ‘struck up one of those wild national airs… [which] turn generally upon the exploits and adventures of Ali Pasha or some other modern hero’. Byron’s telling of the taking of Preveza avoids the ferocity of Ali’s attack and the mutilation of the executed prisoners. These dark deeds had been reported to Napoleon and published by Captain JP Bellaire in 1805, but he judiciously does not mention the beheading of the Greeks in front of Ali or the pyramid of skulls. Byron was receiving a swift education in the shifting alliances of Albanian politics. As he noted ‘some daring mountain-band’ would challenge Ali’s power and ‘from their rocky hold / Hurl their defiance’, but they would not yield; they could always be bought for gold however. Indeed, adaptability was a necessary virtue of survival. As Edward Lear noted of his host when lodging in Himara many years later (1848); a Greek ‘palikar’, he had had an adventurous history as ‘one of the Khimariotes taken by Ali Pasha as hostages, and was long imprisoned at Ioannina; he was also in the French-Neapolitan service, and more lately, one of Lord Byron’s suite at Missolonghi’ during the Greek War of Independence.

Despite any doubts, Byron delighted in the novelty of Albania, liked the Albanians and in a letter to his mother is full of admiration for the Albanian troops, the ‘best in the Turkish service’ and much taken with everything Turkish. Byron’s attitude to things foreign was open. He made a point of not being biased towards Britain, taking everything on merit, and was disappointed with his servant Fletcher for complaining about everything, from the accommodation, the modes of transport, the food and drink, to the lack of tea! Hobhouse did not share Byron’s wholehearted enthusiasm. In his diary he relates that foreigners were not welcome in Epirus, noted the subservience of the local Greeks and the arrogant behaviour of the Turks who happily let off their guns at whoever displeased them. At the same time he introduces his audience to what became the familiar tropes of Orientalist art and literature: the luxury and colour, the chaos and the squalor, the secretive latticed windows of the houses, the bustle of the bazaar.

Fig. 15: The Palace of Ali Pasha at Ioannina from The Life and Works of Lord Byron illustrated by JD Harding, 1835.

Their first encounter with the ferocity of Ali’s rule was on entering his seat of power at Ioannina, where they were sickened by the sight of an arm and part of the right side of a body hanging from a tree. A reminder that Ali’s

| dread command Is lawless law; for with a bloody hand He sways a nation, turbulent and bold: |

420 |

Their first impression was that these were the remains of a robber. Although in his Diary Hobhouse says the sight made he and Byron ‘a little sick’, in his Travels he shows a certain amount of restraint in condemning this spectacle of Eastern barbarity by commenting that it was only fifty years previously that such a sight would have been common within Temple Bar in London. Only later were they made aware it was a part of the unfortunate Euthemos Blacavas, an insurrectionist Greek priest beheaded five days earlier. If it was Blacavas, who had led a nationalist revolt in Thessaly in the spring of the previous year, it had been some time since he was captured, tortured and then executed. Anyone who had read Pouqueville’s rather gloomily gothic account of his own first audience with Ali would have been prepared for such macabre sights. On his second meeting, Pouqueville passed two freshly severed heads stuck on poles adorning the courtyard of the audience chamber. These had not been there the day before, but went unremarked by the mingling clients and petitioners awaiting their turn. Byron’s poetic account is more impressionistic and circumspect, hinting that such dark deeds ‘lurk beneath’, and prophetically that through the stain of Ali’s ‘bloody hand’, ‘bloodier acts conclude those who with blood began’.

Fig. 16: The house of Nicolo Argyris in Janina (1813) by Charles Cockerell, where most of the notable British visitors lodged. Hughes refers to the plate that illustrates his book as a ‘beautiful and accurate view’.

Byron’s likening of Albania with Scotland recognizes perhaps more than a superficial similarity of topography and clan structure, but of poverty and disadvantage well away from the effete world of the court of George III and the Regency. Byron the outsider, not entirely welcome in his own land, was happy to embrace fellow outsiders in a way that other well-bred travellers were not. The examples of Ali’s cruelty were another matter. From the reports these acts would appear as though they were something unique to the East. By twenty-first century standards Ali’s behaviour was appalling, and seemed shocking to many of his visitors, but the superiority of the Westerners towards what they saw as Oriental despotism would give the impression that they were coming from a world that was totally unused to such things. Yet, in Britain ‘Butcher’ Cumberland, George III’s uncle, had not got his nickname for nothing in the aftermath of Culloden (1745–7), it had not been long since the French revolutionaries had displayed their own taste for bloodletting in the dark days of the Terror (1793–4), or the atrocities committed by both sides in the Dos de Mayo Uprising and the Peninsular War (1808–14), so unflinchingly depicted by Francisco Goya in his series of prints The Disasters of War (undertaken between 1810 and 1820).

Ali was not in Ioannina but away on campaign in ‘Illyricum’, as Byron put it, besieging his brother-in-law, Ibrahim Pasha, in the well-fortified town of Berat. The rather put out Leake, whose plans had been inconvenienced by Byron’s arrival, had informed Ali of their visit, paving the way for an audience by telling him that his visitor was a man of great family. In response, Ali had left instructions for Byron to be treated as befitted an ‘Englishman of rank’; everything provided gratis. The guests were put up in the house of Nicolo Argyri Vrettos, a Greek merchant and patient put upon default host for Ali’s foreign guests. Cockerell and Hughes also stayed with Agryri three years later. Hughes found the ingratitude of Ali towards the Vrettos family, which he had reduced to such poverty that they could hardly cope with the upkeep of their house, worthy of comment whereas Byron was much less questioning in his observations.

Once installed in the house of Nicolo Argyri, Byron fell under the spell of the vizier’s generosity and luxury and he and Hobhouse were soon trying on Albanian costume. Byron’s may have been the one he was to wear in his famous portrait by Thomas Phillips, painted in 1813. They were treated royally, shown round Mukhtar’s palace by Hussein, his 10 years old, but very grave, son, who entered into a courteous conversation about the British parliament. He asked the two noblemen whether they were in the Lords or the Commons, thus impressing them with his knowledge of external affairs. Mahomet, Ali’s other grandson, also around 10 or 12 years old, showed them round Ali’s palace, which was said to have 300 chambers. The son of Ali’s second son, Veli, pasha of the Morea, was living in the palace and already had a pashalik of his own.

In contrast to Byron’s fulsome verse, the prose accounts of Hobhouse and Leake dwell on the often shabby appearance of Ali’s retinue and the quaint juxtapositions of Oriental opulence, silks and furnishings, harems and slaves, with haphazard and misjudged attempts at Western taste. All this existed, it was noted, within a region of backwardness and squalor, with the exception of those areas with proximity to Italy and a history of interaction with the outside world. Complaints of the poverty and dirt of the accommodation with its resident vermin are frequent; even if for the seasoned traveller through Italy, the fleas were not necessarily any worse. The population too was often unwashed and the fleas could even be spotted jumping in the divans of Ali’s palace, brought in by the visiting public. Ali, ‘so accustomed to the rudest Albanian life in his youth’, showed no disgust when receiving petitions from the lowest of his subjects, whose dirtiness Leake obviously found hard to bear. Ali treated them with familiarity and allowed them

to approach him, to kiss the hem of his garment, to touch his hand, and to stand near him while they converse with him, his dress is often covered with vermin, and there is no small danger of acquiring these companions by sitting on his sofa, where they are often seen crawling amidst embroidered velvet and cloth of gold.

At the same time, in 1804, Ali had just completed a magnificent audience chamber in the seraglio of the castle that was

not surpassed by those of the Sultan himself. It is covered with a Gobelin carpet, which has the cypher of the King of France on it, and was purchased by the pasha’s agent at Corfu.

Fifteen years later an anonymous American contributor to The North American Review and Miscellaneous Journal (1820), described the palace as being in ‘the Chinese taste’, with small pillars and points on the roof, painted red and white and decorated with large pictures of battles, hunts and ‘wild beasts devouring each other, the work of poor Italian artists’. Indeed this ‘taste’ apparently stretched to opera. This was the young Edward Everett, the first American to visit Ioannina, who had received an introduction to Ali through Byron. On the same visit was a young Venetian opera dancer joining a troupe of Italians to entertain at the wedding of one of Ali’s grandchildren. Such culture clashes appear more frequently than would be imagined in such a remote area. Everett was greeted by a German band playing ‘God save the King’ in Ali’s court at Tyrnavos in Thessaly; Americans were usually taken to be English. Ali’s eclecticism is endorsed by Hughes, who records that the new seraglio at Preveza was adorned with Persian carpets and Venetian mirrors. This was not so uncommon in a changing world. The reforming Sultan Selim III, who was keen to absorb Western influences, decorated his palaces in the Italian style while European fashions were imitated in the capital. Of course the acquisitive owners of the finest European houses and palaces had long been stylistic plunderers. There was an irony in the snobbish criticism of the travellers to Ali’s court, coming as they did from lands with a penchant for chinoiserie and where the Prince Regent himself indulged his own fantasies for Chinese-Islamic pastiche in the Royal Pavilion at Brighton. Eager to counteract what he saw as the naive myopic classicism with which his contemporaries viewed modern Greece, often only to be disappointed with the present reality, Byron plays up the Ottoman in his verse and the acceptance of things as they are, emphasizing the Orientalist vision.

The harem; something of undying fascination to Western writers, and Everett gives it due attention. Nothing, except religion, defined the Oriental more than the harem and the hamam (bath). Ali was said to have anything from 200 to 400 women in his harem (and perhaps 300 boys, called Ganymedes, in the seraglio), depending on whom to believe. Some were slaves from Constantinople, others native Greeks or Albanians, generally volunteers (or had been volunteered) that could be married off at the right moment to the officers of the court, some had been taken by force. According to Everett, Ali at this time had one wife, 25 years old; he was around 70 by this time. Nubian eunuch guards would stand at the door and attend the women on visits to the bath or out in a covered wagon. In the Ottoman court it was common for black eunuchs to guard the harem, as they had been rendered completely sexless as opposed to their white counterparts who served in the administration. As well as his palace in Ioannina, Ali had two summer residences, one at the north of the lake and one in the town. Here he could retire with the ‘most favoured ladies of his harem’. The town retreat, a marble-floored pavilion surrounded by a wild garden, citrus groves, figs and pomegranate, with roaming deer and antelope, contained a central octagonal ‘saloon’ with a marble fountain and an Italian ‘organ’ playing Italian tunes. Hobhouse’s diary adds that the gardens were in disarray and the organ was a water-organ. Typical of the strange amalgam of East and West, the pavilion was said to be the handiwork of a Frenchman, perhaps a onetime prisoner. Hughes comments on the use of foreign designers, obtained by whatever means. The extensive gardens of the Tepelene seraglio were the creation of two Italian gardeners, ‘somewhat in the style of their own country’. Deserters from the French Army in Corfu whom Ali had taken in, he provided them with houses, a good salary, and wives from his own harem. The exotic picture at Ioannina was completed by the scenes, which Hobhouse did not witness but eagerly imagined, of Ali cavorting with members of his harem, some of whom would dance to an Albanian lute as he reclined on a sofa, to indulge in ‘the enjoyment of whatever accomplishments these fair-ones can display for his gratification’.

Fig. 18: Ali’s grandsons, Ismail and Mehmet (1825) by Louis Dupré.

Ali’s exploits were not only being told in song but stories about him were widely circulated. Hobhouse records that hardly had his party stepped ashore before they learnt from a Greek teacher in Arta that Ali, ‘having made the most of his youth’ suffered from an incurable disorder with the symptoms of secondary syphilis. Rumours of his lurid exploits were common currency: the debaucheries of his court, the oriental splendour, the gold, silks, jewels, the activities of the concubines and scores of pages, the young orphaned sons of parents he had murdered and attached to him like puppies; Ali, bored with his courtiers, roaming the streets of Ioannina in the night disguised as a merchant, in search of adventure. One of the most notorious stories doing the rounds concerned the drowning of twelve young maidens in the Lake at Ioannina on the orders of Ali. This incident took on a life of its own, reaching a large international audience by its mention in The Gaiour (infidel), published in 1813, in which a Venetian Christian extracts revenge for the drowning of his lover Leila, a slave and member of the harem, by the Emir Hassan. Byron set the narrative in the recent past, the abortive Russian-backed rising of the Greeks in the Morea of 1770 which was put down by Hasan Pasha. A note at the end however acknowledges the inspiration of the Ioannina lake drowning. Byron claims factual credence by recounting Ali’s use of drowning as a punishment, the details of which he heard in part from Vassily, his guide supplied by Ali, who claimed to have been an eyewitness to events. In essence the wife of Mukhtar Pasha complained to Ali that her husband had been unfaithful. She supplied a list of his supposed twelve beautiful lovers, who were then seized, tied in a sack and drowned in the lake the same night without a cry. Phrosyne, in Byron’s account, the fairest of the twelve, then became the subject of many a local ballad and coffeehouse story that had spread throughout the region.

Fig. 19: Ioannina with Ali’s citadel by Finden.

The numbers of the victims vary. Cockerell heard the tale from Psalidas, the schoolteacher of Ioannina, who also told him of Ali’s massacre of the villagers of Gardiki in 1799. By then it had more details and a new twist. Phrosyne, now Euphrosyne, was a celebrity who attracted a host of admirers due to her wit and beauty. The dissolute Mukhtar became her lover, but his wife was the daughter of the pasha of Berat whose friendship Ali was at that time especially anxious to cultivate. Ali burst in on Euphrosyne with his guard at midnight and after calling her the seducer of his son and other names, he forced her to give up whatever presents he had made her, and had her led off to prison with her maid. Next day, in order to make a terrifying example to check the immorality of the town in general and his son in particular, he had nine other women of known bad character arrested, and they and Euphrosyne were led to the brink of the precipice over the lake on which the fortress stands. Her faithful maid refused to desert her, and with echoes of the Suliote women, she and Euphrosyne, linked in each other’s arms, leapt together down the fatal rock followed by the others. Another version had it that Mukhtar had refused to give his wife an emerald ring, but had given it to Euphrosyne, whose husband was away in Venice. It was rumoured she had also turned down the advances of Ali. Ali arranged a dinner inviting Euphrosyne, and a selection of the most charming and elegant ladies and some prostitutes. His policemen then burst in, tied them up and shut them in a church all day by the lakeshore, telling them they were condemned to death. The women supposed that Ali was expecting them to be ransomed. That night Euphrosyne and sixteen other girls were drowned in the lake.

George Finlay, who fought with Byron during the Greek War of Independence, told the tale in his History of the Greek Revolution (1861) some years later by which time it had become even more colourful. Euphrosyne was the beautiful 28 years old niece of Gabriel, the archbishop of Ioannina, who spent too much time reading ‘naughty’ episodes in classical literature rather than studying the saints, which led her to revive the customs of the hetairai, the educated courtesans of ancient Greece. While her husband was away in Venice, hoping to keep away from Ali’s designs on his wealth, Euphrosyne was entertaining the wealthy young men of the city and enticing the attention of Mukhtar who showered her with gifts. Her behaviour caused scandal and encouraged imitators, to the outrage of the pious, both Christian and Muslim. After the complaints of Mukhtar’s wife and under a veil of public duty, or even out of rejected jealousy, Ali decided that such activities had to be stopped and punished. Following their arrest, Euphrosyne and her accomplices were held in the Church of Saint Nicholas, until the next night when they were rowed across the stormy lake in small boats and summarily thrown overboard, without being tied up in sacks as was the custom, to drown with solemn dignity. Again Finlay attests to the eyewitness account of one of the guards. The Christian population was indignant and the funerals of the women drew large crowds, but Ali, apologizing for the severity of his justice, justified his actions by saying he would have pardoned them but no one had stood up to intercede for them.

Such incidents and the notoriety of Ali’s propensity for acts of cruelty as reported in the West only seemed to add to his mystery and romance. In fact many of his punishments were part of the Ottoman culture. The drowning of women in sacks was the result of a Turkish taboo against the shedding of female blood; a common punishment for the prostitutes of Constantinople was to end up in the Bosphorus. The extreme case was when the Sultan Ibrahim I (1640–1648) was rumoured, in a fit of madness, to have ordered his complete harem of 280 to be drowned. Suffering was used particularly to deter brigandry, rebellion or political offences. Thus impalement, sometimes using the stake as a spit so that the victim could also be roasted alive, was not uncommon. Hughes reported that despite initially disbelieving the stories he was told on good authority that criminals were roasted alive over a slow fire, impaled, and skinned alive. Sometimes they had their extremities chopped off or the skin of their face stripped over their necks. While still alive the victims were able to plead for water to no avail, as the populace was too afraid to help. Leake saw a Greek priest, the leader of a gang of robbers, nailed alive to the outer wall of the palace at Ioannina in sight of the whole city. On his own death Ali’s head was sent to the Sultan in Constantinople. This was a recognized end for offenders where heads were displayed outside the palace.

On setting out for Ali’s palace at Tepelene, Byron, who seemed determined to see everything in terms of a great new adventure, proudly asserted that he was the first Englishman, with the exception of Leake, to venture ‘beyond the capital into the interior’. The Frenchman, Pouqueville, of course had also travelled extensively throughout Albania and Leake admonished Hobhouse for relying with too much credence for background information from Pouqueville, ‘who is always out’. In reality, neither Hobhouse nor Byron, nor any of the other English writers had much to say in his favour, often criticizing him for his inaccuracies and anti-British bias, but happy to plunder his writings when it suited them. When they arrived at Tepelene on a baking late afternoon, Byron was typically reminded of Scott’s description of Branksome Castle in his Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805) and, allowing for the difference in dress, its feudal customs. The pomp, ceremony and colour of the court made a deep impression. Byron was more taken by the show of military activity than the reality that Ali, inconveniently, was actually at war. Ali had around 5,000 men actively besieging Berat, so the palace was obviously on a war footing, with messengers coming and going from the front line. While Byron shows little interest in the wider military picture, the warlike nature of the Albanians, whom he believed all to be brave, rigidly honest and faithful, capture his imagination. He wrote to his mother describing the pomp of the court:

The Albanians in their dresses (the most magnificent in the world, consisting of a long white kilt, gold worked cloak, crimson velvet gold laced jacket and waistcoat, silver mounted pistols & daggers), the Tartars with their high caps, the Turks in their vast pelisses11 & turbans, the soldiers & black slaves with the horses… in an immense open gallery in front of the palace, the latter placed in a kind of cloister below it, two hundred steeds ready caparisoned to move in a moment, couriers entering or passing out with the despatches, the kettle drums beating, boys calling the hour from the minaret of the mosque.

Again Hobhouse is less awestruck than Byron. As the visitors followed ‘an officer of the palace, with a white wand’, they approached their audience with Ali by proceeding ‘along the gallery, now crowded with soldiers, to the other wing of the building, and… over some rubbish where a room had fallen in, and through some shabby apartments… into the chamber in which was Ali himself… a large room, very handsomely furnished, and having a marble cistern and fountain in the middle, ornamented with painted tiles, of the kind which we call Dutch tile’.

When finally ushered into the presence of the vizier, visitors were confronted with a decidedly portly man of medium height, around 60 years old, with a long white beard and deceptively benign aura, and sharp light blue eyes. Ali received Byron with respect and hospitality, standing up to greet him and flattering him by saying he could see he was a ‘man of birth’ because he had ‘small ears, curling hair and little white hands’. He was not magnificently dressed, but wore a high turban of fine gold muslin and his waist was adorned with a yataghan, or short sabre, studded with diamonds. Though he knew Ali cruel, Byron was impressed by his courtesy and military reputation:

his manner is very kind & at the same time possess that dignity I find universal amongst the Turks. - -

He has the appearance of anything but his real character, for he is a remorseless tyrant, guilty of the most horrible cruelties, very brave & so good a general, they call him the Mahometan Buonaparte. Napoleon has twice offered to make him King of Epirus, but he prefers the English interest & abhors the French as he told me. He is of so much consequence he is courted by both, the Albanians being the most warlike subjects of the Sultan, though Ali is only nominally dependent on the Porte.12 He has been a mighty warrior, but is as barbarous as he is successful, roasting rebels etc., etc.

Rather than being confronted with a lion in his prime Byron had met more of a wily old fox, to whom age had bestowed the air of an almost otherworldly fatherly humility and wisdom. On his way to Tepelene, Byron had experienced first-hand the brutal acts of repression and petty disregard for the ordinary people, turfed out of their homes to give Byron’s party lodgings, but this experience of the arbitrary and avaricious nature of Ali’s government contrasted with the courtly display only seemed to give an added frisson to their audience. The comparison of Ali with Napoleon was enough of an accepted fact by this time to go unquestioned, though after his death, in the Introduction to ‘Les Orientales’ (Oeuvres Complètes de Victor Hugo, 1829), Victor Hugo made the comparison with reservations. Ali was ‘the only colossus of this century who can be compared to Bonaparte… and is to Napoleon as the tiger to the lion, or the vulture to the eagle’.

Pouqueville had been less impressed. He found that Ali did not measure up to what he had imagined from the stories he had heard. In his Voyage en Grèce (1826–7), he elaborates slightly on his previous accounts, perhaps with the flourishes of hindsight that emphasize Ali’s 60-odd years of age. Ali again greeted them standing:

He saluted us, embraced M. Bessières, and drawing himself back in a tottering attitude; he let himself fall backward on the corner of a sofa, apparently without having perceived me. A spectre, with a white beard, accoutred in black, who was present, honoured me with a slight movement of the head to intimate that I was welcome.

Despite the doddery appearance of the corpulent and wrinkled Ali, his Greek secretary lies prostrate on the floor in a state of fear. Pouqueville was excited to see the man who styled himself as a second Pyrrhus, ‘a new Theseus – an aged warrior covered with wounds’, but what he found was someone whose ‘suppleness of the motions of his countenance; the fire of his little blue eyes; impressed on me the alarming idea of deep cunning, united with ferocity’.

Byron in a note to Childe Harold, called Pouqueville’s account in his Travels of the ‘celebrated Ali’ incorrect. Byron, however, was lavished with attention. Ali entertained Byron and Hobhouse with refreshments and pipes, showed them a mountain howitzer in his apartment, while boasting he also possessed several large cannon, and an English telescope, through which Hobhouse tells us, Ali laughingly explained that the man ‘they saw on the road is the chief minister of my enemy, Ibrahim Pasha, and he is now coming over to me, having deserted his master to take the stronger side’. His genial manner impressed them, while giving little away. He did say, though, that the British Navy had taken Zante (Zakynthos), Cephalonia, Ithaca, and Cerigo (Kythera). Congratulating them upon the news, which had arrived a fortnight before, he said he was happy to have the English as allies, believing they would not undermine his authority like the Russians and French by protecting runaway robbers, for which read insurgents. He went on to profess that he had always been a friend of Britain ‘even during our war with Turkey, and had been instrumental in bringing about a Peace’.

Despite the opulence of Ali’s court, Cockerell describes Ali, in contrast to his son Mukhtar, as displaying an austere sobriety. Mukhtar had turned from a happy and open youth to a gloomy and ferocious adult, while still leading a dissolute life. Everett paints a picture of the mainly Muslim elite living a life of luxury and depravity while the peasants struggled in abject poverty. Ali was calculated in the image he projected to his Western visitors, playing up the venerable old man, with a manner that Cockerell found ‘so mild and paternal and so charming in its air of kindness and perfect openness’ that the contrast with his reputation is the more chilling. Ushered into his presence Cockerell, ‘remembering the blood-curdling stories told of him, could hardly believe [his] eyes’. Accompanied by George Foresti, who had replaced Leake, they were confronted with Ali, ‘a truly Oriental figure’, seated on a crimson sofa trimmed with gold.

He had a velvet cap, a prodigious fine cloak; he was smoking a long Persian pipe, and held a book in his hand. Foresti says he did this on purpose to show us he could read. Hanging beside him was a small gun magnificently set with diamonds, and a powder-horn; on his right hand also was a feather fan. To his left was a window looking into the courtyard, in which they were playing at the djerid,13 and in which nine horses stood tethered in their saddles and bridles, as though ready for instant use.

Later Cockerell visited Mukhtar, who, although he was also in good-humour, was:

without any of the inimitable grace of his father, which makes everything Ali says agreeable… Mukhtar’s talk was flat… very civil and rather dull. He smoked a Persian pipe brought him by a beautiful boy very richly dressed, with his hair carefully combed, and another brought him coffee; while coffee and pipes were brought to us by particularly ugly ones. On the sofa beside him were laid out a number of snuff-boxes, mechanical singing birds, and things of that sort. The serai itself was handsome in point of expense, but in the miserable taste now in vogue in Constantinople. The decoration represented painted battle-pieces, sieges, fights between Turks and Cossacks, wild men, and abominations of that sort; while in the centre of the pediment is a pasha surrounded by his guard, and in front of them a couple of Greeks just hanged, as a suitable ornament for the palace of a despot.

All visitors to Ali were intrigued by how he had attained his position, and where he had come from, and various accounts of his life were a common feature of the travel books, often repeating the same tales. In essence it was a story of a climb from disinherited obscurity to power by way of banditry and cunning. Hughes was told of the days when Ali had ‘not where to lay his head’ and how his mother possessed ‘all the martial qualities of an Amazon’. Once enough power was amassed, Ali was able militarily to take on increasingly larger opponents, while always appearing to serve his ultimate master, the Sultan; whether distinguishing himself against the Austrians and Russians, or the Bosnian rebel Osman Pazvantoğlu (Paswan Oglou), but at arm’s length from the seat of power in Constantinople. As Byron put it in a nutshell:

Ali inherited 6 dram and a musket after the death of his father … collected a few followers from among the retainers of his father, made himself master, first of one village, then of another, amassed money, increased his power, and at last found himself at the head of a considerable body of Albanians.

The truth was of course more complex, but a rags-to-riches tale was the pleasingly more satisfying. There was even a rumour that he had overcome his destitute state by discovering a pot of gold hidden under a tree, which enabled him to hire his first followers. The story, attested by Guillaume de Vaudoncourt but doubted by Pouqueville who says it was invented by the Greek scholar Psalidas, was too good to leave alone, and it became part of the repertoire of Ali tales.

Ali told Byron to consider him as a father whilst he was in Turkey, while he looked on him as a son. Byron and Hobhouse stayed four nights. The scent of the forbidden lurks in their accounts. Byron was open about his homosexual desires in letters to friends and homosexuality was a further mysterious element in the mix of Ali’s personality. Byron had intimated that one of his reasons for undertaking his tour was to inquire into the praiseworthy nature of sodomy from ancient times onwards and he made no secret of his affairs with local boys while in Greece. Hobhouse notes in his Diary that Ali looked ‘a little leeringly’ at Byron. He then showered Byron with gifts of sweets as for a child and requested that he visit ‘often, and at night when he was more at leisure’ and by implication, on his own. Peter Cochran suggests that the discrepancy between the number of meetings recorded by Byron and Hobhouse raise the possibility that Byron indeed saw Ali on his own and was probably entertained by his Ganymedes. At Tepelene, one of Ali’s doctors, a Frank and native of Alsace,14 the son of an eminent physician from Vienna, informed them that Ali’s body was unscathed and that within groups with a lack of females ‘pederasty… was openly practised’.

In contrast to Ibrahim Manzour, who stressed the dangers of travel amidst the savage inhabitants of Albania along ‘bad roads that are both dangerous and disagreeable’, the hospitality of Ali and his son Veli impressed Byron enough for him to write in his notes on Childe Harold that the difficulties of travelling in Turkey had been greatly exaggerated. In fact Byron preferred Turkey, as he calls it, to Spain and Portugal. It should be remembered that he had special treatment, always being looked after with guards and his every requirement being catered for. Ali gave him a bodyguard of forty men to escort him through the dangerous passes. Byron then went on to stay with Veli Pasha in the Peloponnese on his way to Athens and was treated even more generously as a brother. In a letter to Hobhouse from Patras on his way to Athens and to Francis Hodgson from Athens, he boasts of having received a stallion from ‘the Pacha of the Morea’, Veli, who ‘received him with great pomp, standing, conducted me to the door with his arm around my waist, and a variety of civilities, invited me to meet him in Larissa [in Thessaly] and see his army’. Other travellers agreed with Manzour, attesting to dangers and discomforts real enough.

In retrospect it seems strange that it was not until Byron and Hobhouse had left Ali and returned to Vostitsa, on the Gulf of Corinth, that they realized to their surprise the enmity between the Greeks and Turks. Hobhouse wrote in his journal, ‘We have observed the professed hatred for their masters to be universal among the Greeks.’ Until then, under the spell of Ali, they had thought Albania and Greece to be tranquil provinces of the Empire. It too dawned on them that their visit, oiled as it was by the wheels of British diplomacy, was not as innocent as they thought. Perhaps they had been used; unaware of British imperialist designs they were only too eager to go as supplicants to Ali’s court. The Romantic Ali would be the image that Byron would portray in verse, even if in reality he knew more.

An ambiguity remains in Byron’s vision of Albania and Greece. When he realized that he and his alter ego, Harold, were travelling through an enslaved culture under Turkish will, he was already indebted to the hospitality of the masters. The revulsion and admiration he feels for Ali and the brutality of bandit law are never resolved. In Childe Harold (1812) on the one hand he wallows in Ali’s bloody deeds, only then to remember, ‘Fair Greece! sad relic of departed worth!’ and the ‘Spirit of Freedom!’, and ‘the scourge of Turkish hand’ that holds the populace enslaved.

Though Byron’s sympathies shifted, he never totally gave up his feeling for the Turks, even during the Greek War of Independence. For Hobhouse too, the situation was complex; the Suliotes are bandits not freedom fighters, whose songs commemorated robbing exploits (Byron’s song beginning ‘Tambourgi, tambourgi’ is punctuated by ‘Robbers all at Parga!’). Again, it was only when the Suliotes came in on the Greek cause of liberty that perceptions changed.

In Byron’s view he had been an explorer, almost another Columbus, bringing back riches from an exotic and faraway land. As he wrote to Henry Drury in 1810:

Albania indeed I have seen more than any Englishman (but a Mr. Leake) for it is a country rarely visited from the savage character of the natives, though abounding in more natural beauties than the classical regions of Greece… where places without name, and rivers not laid on maps, may one day when more known be justly esteemed subjects for the pencil and pen.

When not in poetic mode, Byron was an accurate observer, as later travellers attest. Edward Lear backs up Byron’s account of Albanian singing and is more outraged by the use of women as pack animals and general drudges by their menfolk, set to employment ploughing, digging, sowing and repairing the highways. Byron’s description of Albania in the notes to Childe Harold impressed the mountaineer Bill Tilman, who served with the partisans in the Second World War and wrote When Men and Mountains Meet (1946). Paddy Leigh Fermor commented on Byron’s accurate eye for women’s costume in Roumeli: Travels in Northern Greece (1966), when he found little changed. But it was the poetic Byron that was the one that mattered, and had the more profound influence.

Although the Europeans at Ali’s court reported their personal experience, they were drawn to reinforcing the Westerner’s stereotypical view of the East. From Pouqueville onwards, who despite his position was more concerned with Ali’s appetites, atrocities and scheming than his administration and place within the international context, they played up the otherness, with the result that Ali becomes an all purpose caricature of the Oriental despot, with all the expected vices and contradictions. Byron took Pouqueville’s Ali and sprinkled magic dust on him, with the result that, despite his basis of authenticity, his Albanian excursion in Childe Harold had more in common with the fictitious writings of Chateaubriand, something he was loath to concede. François-Auguste-René, Vicomte de Chateaubriand, his political opposite, diplomat and founding figure in French romanticism, had visited America and the East; he only got as far as Corfu before heading south to Greece and the Levant in 1806–7. His subsequent travel writings were fanciful and his two works of literature Atala (1801) and René (1802) about the Native Americans, although purporting to have the air of veracity were not based on actual experience. Atala and Childe Harold are both works of exile and disillusion, the events of which explore the exotic, taking place on the edge of civilization. In Atala it was commonly believed that Chateaubriand was extolling the virtues of the ‘noble savage’, although he denied this, and Byron’s Albanians too have the same primitive qualities. Byron’s visit to Ali was a pivotal moment in his life; he began Childe Harold only a week after. And he had read Chateaubriand, a debt Chateaubriand felt Byron never acknowledged. The result is that the Ali episode gives off the air of exotic adventure despite its basis in fact. Because of the fame of Childe Harold, in European eyes Ali becomes a character inhabiting another world, rather than a real person, something which later narratives did little to dispel.

To assess whether Thomas Hughes was correct in his statement that ‘the three greatest men produced in Turkey during the present age, have all derived their origin from Albania… the late celebrated Vizir Mustafa Bairactar,15 Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt, and, the greatest of them all…’ Ali Pasha, we shall have to look behind the myth.

1 Mt Tomorr; the highest peak in Southern Albania (2,416m/7,927ft) and a highly visible landmark.

2 Aoös (Greek), Vjosë, Vjosa (Albanian) flows from Greece into Albania where it is joined by the Drino near Tepelenë.

3 Tepelenë, the site of Ali Pasha’s palace.

4 Harem, the women’s quarters in the palace reserved for wives, concubines and slaves.

5 Muslim monk or hermit often regarded as a saint; in Albania specifically a dervish, usually a Sufi who has taken vows of poverty and austerity, and particularly of the Mevlevi order known for their ‘whirling’ dance.

6 Ali Pasha.

7 Fourteenth century Persian poet whose verses celebrating love, wine and nature are traditionally treated as allegoric by Sufis.

8 Anacreon, a Greek lyric poet (c.582–c.485BC) from Teos in Asia Minor, famous for his drinking and love songs and poems.

9 Completed in 1797 but not published till 1816.

10 Apart from unauthorized English editions becoming widely available, within ten years extracts from Childe Harold were translated into Portuguese (1812), then Spanish, German, French, Dutch, Italian, Russian, Polish and Hungarian; Hobhouse’s Travels in Albania and other provinces of Turkey in 1809 and 1810 went through a number of revisions and editions.

11 Short fur-lined jacket like those worn by the Hussars.

12 Refers to the Sublime Porte, the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

13 A combat game involving a horseman throwing a blunted spear at an opponent.

14. Peter Cochran suggests this was Ibrahim Manzour, but there is no evidence he was in Epirus until 1814.

15 Alemdar Mustafa Pasha, grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire (d.1808) who overthrew Mustafa IV and instated Mahmud II against the will of the janissaries.