Japanese individual and infantry crew-served weapons were adequate (with the notable exception of AT weapons), even though they had been developed in the 1920s and 1930s, and sometimes even earlier. They were rugged and fairly reliable, but were comparatively short ranged and did not match the capabilities of contemporary Western weapons in most cases. The short range of infantry weapons was not much of a hindrance in the Pacific though, and the Japanese became adept at employing them offensively and defensively to exploit this characteristic. Their lack of sufficiently heavy and long-range artillery proved to be more of an issue though. This, coupled with outdated fire-control measures, caused them significant problems. Ammunition packaging proved to be inadequate for the extremes of the tropics and was more troublesome than the weapons themselves.

The Arisaka 6.5mm Type 38 (1905) and 7.7mm Type 99 (1939) rifles, while heavy and not as finely finished as Western counterparts, were as reliable and rugged as any five-shot bolt-action in service. These rifles had a Mauser-type action stronger than the US M1903 Springfield’s. Other versions of the 6.5mm Type 38 included the Types 38 (1905) and 44 (1911) carbines, the latter with a permanently attached folding spike bayonet; Type 38 (1905) short rifle; and Type 97 (1937) sniper rifle with a 2.5x scope. The 7.7mm Type 99 was provided in two lengths, the long rifle for infantry and the short rifle for cavalry, engineers, and other specialty troops (test 7.7mm carbines had too hard a recoil). The long rifle was 50in. in length while the short’s was 6in. shorter. Various units within a division carried spare rifles, totaling almost 2,000.

Japanese automatic pistols were of poor quality and lacked knockdown power. The Nambu Type 14 (1925) and the even more poorly designed Type 94 (1934) had eight and six-round magazines, respectively. Both fired an underpowered 8mm cartridge. Rather than being issued as an improvement over the Type 14, the Type 94 was produced only as a lower-cost alternative. Pistols were issued to officers and crew-served weapons’ crewmen.

In the mid-1920s, the IJA adopted the bicycle to improve infantry mobility. One battalion in some regiments was equipped with them. Some regiments deployed to Southeast Asia were entirely equipped with bicycles. A bicycle-mounted infantry battalion could average 10–15 mph if necessary, and could carry rations for up to five days. Troops would walk beside their bicycles for a short time each hour to exercise different leg muscles to prolong their endurance.

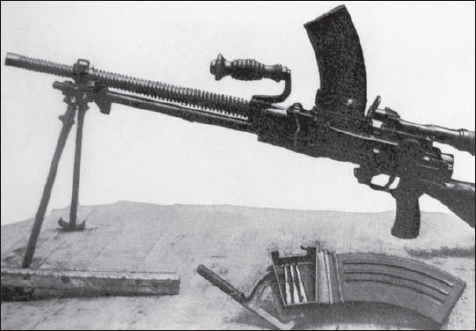

The core weapon of the Japanese section (squad) was the light machine gun. This 6.5mm Type 96 (1936) LMG is shown with a spare 30-round magazine and a magazine loader/oiler. The 7.7mm Type 99 (1939) was similar in appearance, but had a cone-shaped flash suppressor and a folding monopod butt support. Both were based on the Czechoslovakian Brno design, the same weapon from which the British Bren gun was derived.

| Japanese weaponry and equipment designation characters | |

| Character | Meaning |

|

Type |

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

5 |

|

6 |

|

7 |

|

8 |

|

9 |

|

10 |

| A note on Japanese designations: the terms “type” and “model” were both used to translate the Japanese Kanji ideograph Shik, which is actually “type.” The Japanese ideograph for “model” is Kata. Contemporary intelligence documents often used both terms in the same document. “Type” is used throughout this book and “Model” is used for sub-variants. | |

The Nambu 6.5mm Type 96 (1936) and 7.7mm Type 99 (1939) LMGs were bipod-mounted and fed by 30-round top-fitted magazines. The obsolete Nambu 6.5mm Type 11 (1922) LMG was issued as a substitute to some units and even found alongside the Type 96. It had a unique feed hopper in which 6 five-round rifle charging clips were stacked. This tended to collect dirt and vegetation debris, causing it to jam. Besides its bipod, a tripod was available for the Type 11.

The Japanese had some problems with their LMGs. Their rapid extraction sometimes caused stoppages. To overcome this the Type 11 had a complex oil reservoir, which had to be kept full to oil the cartridges as they were fed. The Type 96 required its cartridges be oiled before loading in the magazine, which was accomplished by an oiler built into the magazine loader. A special reduced-charge round was issued. Standard-load 6.5mm rifle rounds could be used, but with an increased chance of stoppage. The 7.7mm Type 99 was an improved Type 96. It was designed to eliminate the need for lubricated ammunition. Both the types 96 and 99 had 2.5x telescopic sights, quick-change barrels, carrying handles, and little used shield plates. To emphasize the Japanese propensity for close combat, these 20 lb weapons could be fitted with a rifle bayonet.

Japan adopted the 7.7mm round for rifles and LMGs on the eve of the Greater East Asia War, fielding the first weapons in mid-1939. The 6.5mm had performed poorly in China where a longer range, greater power, and more penetration were needed. Divisions and brigades in Japan were the first to be armed with 7.7mm weapons, followed by units in China, then Manchuria and lower priority units in all areas. By the time of the invasion of the south some units deploying from Manchuria still had 6.5mm weapons. It was not uncommon for units deployed to a given area to be armed with different caliber weapons, causing ammunition supply problems.

The 5cm Type 89 (1929) heavy grenade discharger was not only an important close-combat weapon, but was also provided with a full range of colored signal smoke and flares. Besides rifled high explosive (HE) and white phosphorus mortar rounds, the Type 89 could fire hand grenades with a propellant charge fitted. The Type 10 (1921) grenade discharger was still issued as a substitute. Popularly called “knee mortars” by Allied troops due to their curved base plate, these compact weapons could not be fired from the thigh, as was rumored, without breaking a leg. Another theory for the source of their nickname is that they were carried in a canvas bag strapped to the thigh—whereas in fact they were carried in a canvas case slung from the shoulder. The Type 100 (1940) rifle grenade launcher was of the cup-type fitting on 6.5mm and 7.7mm rifles. It fired the Type 97 (1937) HE grenade, also the standard hand grenade.

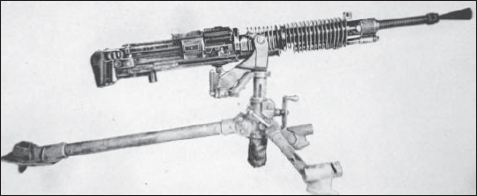

This Nambu 6.5mm Type 3 (1914) HMG equipped battalion machine-gun companies. It was partly replaced by the 7.7mm Type 92 (1932). The two weapons were similar in appearance. The Type 3 had vertical spade grips with large cooling fins on the rear half of the barrel. The Type 92 had two horizontal pistol grips and large cooling fins on only a quarter of the length of the barrel with smaller ones on the rest. Both were based on the French Hotchkiss.

The battalion machine-gun company was armed with either Nambu 6.5mm Type 3 (1914) or 7.7mm Type 92 (1932) HMGs. Even though these tripod-mounted weapons were fed by 30-round metallic strips, a high rate of fire could be maintained. AA adapters could be fitted to both weapons’ tripods and there was a special AA tripod for the Type 3. The 7.7mm HMG used a semi-rimmed cartridge, which could not be fired in rifles and LMGs. The semi-rimmed round had been adopted seven years before the new rifle and LMG round.

Another weapon was the 2cm Type 97 (1937) AT rifle. Capable of semi- and fully-automatic fire with a seven-round magazine, it was surprisingly effective against light tanks and personnel. Its AP-tracer and HE-tracer rounds were not interchangeable with the 2cm machine cannon’s. It was heavy, at 150 lbs, and expensive to produce resulting in its limited issue. Units possessing them normally issued them to the battalion gun company, alongside the 7cm infantry gun.

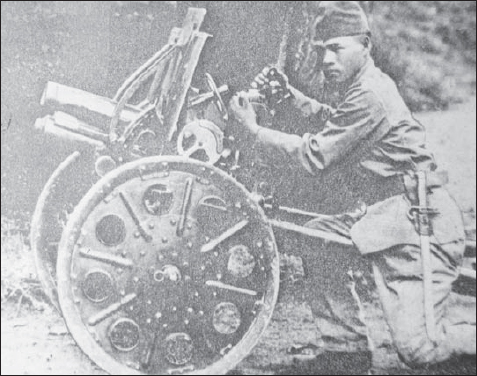

The 7cm Type 92 (1932) battalion infantry gun was issued on the basis of having two in the battalion gun platoon. A few units had a battalion gun company with four pieces. A complex weapon, it nonetheless provided effective direct and indirect fire support. All Japanese infantrymen were issued a Type 30 (1897) bayonet with a 15.75in.-long blade, whether they were armed with a rifle or pistol, or even if they were unarmed.

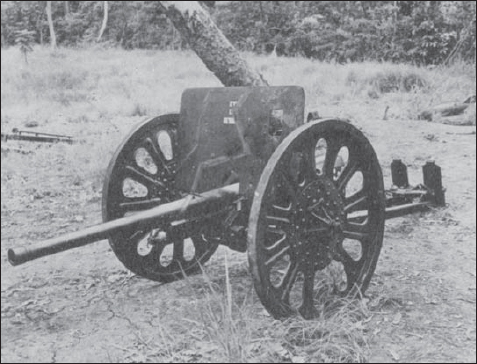

The 3.7cm Type 94 (1934) rapid-fire infantry gun was originally designed as an infantry support weapon for knocking out machine-gun nests. However, it served as the main Japanese AT gun—a role for which it was ill suited, but in which it remained until the war’s end.

The 7cm Type 92 (1932) battalion gun was a comparatively compact weapon weighing 468 lbs, and it could be broken down into a half-dozen man- or animal-pack loads. It had a range of 3,060 yds with HE, AT shaped-charge, and illumination rounds. Normally there were no crew-served weapons assigned at company level, but some units did possess company weapons platoons, which may have had a few HMGs and AT rifles. Otherwise, these weapons could be attached to companies from the battalion.

The regimental gun company was equipped with the 7.5cm Type 41 (1908) infantry gun (a.k.a. the regimental gun) to provide direct and indirect fire. Comparatively compact and light (1,180 lbs), it could be broken down into six packhorse loads. This weapon was originally adopted as a mountain artillery piece, but when replaced by a new 7.5cm gun in 1934 it was relegated to the infantry-gun role. It was provided HE, shrapnel, armor-piercing high explosive (APHE), AT shaped-charge, and white phosphorus rounds and had a 7,000yd range. The ammunition was not interchangeable with 7.5cm artillery rounds.

The principal Japanese ‘antitank’ gun was the 3.7cm Type 94 (1934) infantry rapid-fire gun. Originally intended to deliver direct fire to knock out machine guns, it was provided with HE ammunition. Even though an APHE round was issued, it performed poorly as an AT gun owing to its low velocity and poor penetration. It could knock out a US light tank with multiple hits though. Some units deploying from China were armed with more effective 3.7cm Type 97 (1937) AT guns. These were German-made Pak.35/36 guns captured from China.

While Japanese artillery pieces were upgraded or replaced by new models between 1925 and 1936, no new designs were fielded after that point. The earlier Japanese artillery pieces were based on German Krupp designs, while the new models were based on the French Schneider. The newer guns had longer barrels, improved velocity, increased elevation and traverse, and split trails rather than box trails; they could be towed by vehicle too, though most were still horse-drawn as towing by vehicle proved to be impractical on Pacific islands and in Southeast Asia jungles. Most still had wooden-spoked wheels.

The 7.5cm Type 94 (1934) mountain gun weighed 1,200 lbs. It equipped half of the 12 divisional artillery regiments committed to the Southern Operations. The metal ammunition containers each held six rounds and weighed 118 lbs when full. A packhorse could carry two containers.

The standard divisional artillery piece was the 7.5cm Type 38 (1905) improved gun. This weapon was an improved version of the original Type 38 in 1915, with barrel trunnions further to the rear for increased elevation, improved equilibrators to counter the heavy barrel, a variable type recoil system, and an open box trail to further increase elevation. Even with these improvements it was still an obsolescent weapon barely adequate for its role. It had a 10,400yd range and could fire 10–12 rounds a minute for short periods. Ammunition included HE, APHE, shrapnel, white phosphorus, chemical, and illumination rounds.

The 7.5cm Type 95 (1935) gun was intended to replace the Type 38, but saw very limited issue. It offered a number of design improvements and a split trail, but only a 1,220yd range advantage. An even less common weapon was the 7.5cm Type 90 (1930). It was a more modern design than the Type 95 and intended for truck-towing, being provided with pneumatic tires. It was mainly issued to independent artillery regiments and tank units. A spoked-wheel version did see limited issue to divisional artillery regiments. It had a longer barrel than other models and was fitted with a muzzle break and long split trails. This gave it a higher muzzle velocity and its wider traverse made it an effective AT weapon. Both the types 95 and 90 used the same ammunition as the Type 38. Many divisional artillery regiments were armed with the 7.5cm Type 94 (1934) mountain gun. It could be broken down into 11 components for six packhorse loads. While using the same ammunition as other 7.5cm guns, its range was only 9,000 yds.

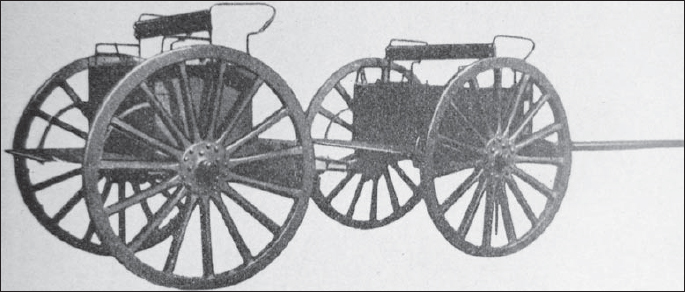

Most Japanese field artillery was horse-drawn. This 7.5cm field howitzer caisson (left) held 60 rounds, and the limber 40 rounds, and was drawn by six horses.

Japanese “10cm” weapons were actually 105mm weapons. The 10cm Type 91 (1931) howitzer equipped both divisional and independent artillery regiments, although few divisions were provided with a 10cm battalion. It could be found with both pneumatic tires and wooden-spoked wheels. The weapon could fire HE, APHE, shrapnel, and white phosphorus to 11,500 yds at a rate of six to eight rounds a minute. Medium artillery regiments had the 10cm Type 92 (1932) gun. It fired HE, APHE, shrapnel, and white phosphorus to 20,000 yds. It required a different type of ammunition to the 10cm howitzer. This weapon was known for its comparatively long range, making it difficult to detect in hidden jungle positions. On Guadalcanal the Marines dubbed these guns “Pistol Petes.” A 10cm mountain howitzer was also available in pack transport form. It only had a 6,000yd range and its HE and illuminating rounds were entirely different to other 10cm ammunition types.

Heavier, non-divisional artillery included the following:

| Weapon | Range |

| 12cm Type 38 (1905) howitzer | 6,300 yds |

| 15cm Type 38 (1905) howitzer | 5,450 yds |

| 15cm Type 4 (1915) howitzer | 10,800 yds |

| 15cm Type 96 (1936) howitzer | 13,000 yds |

| 15cm Type 89 (1929) gun | 27,450 yds |

| 24cm Type 45 (1912) howitzer | 15,300 yds |

| 24cm Type 96 (1936) howitzer | 15,300 yds |

| 30.5cm Type 7 (1918) short howitzer | 13,000 yds |

| 30.5cm Type 7 (1918) long howitzer | 16,600 yds |

| 32cm Type 98 (1938) spigot mortar1 | 1,200 yds |

| Notes: | |

| 1 Often designated 25cm for the spigot diameter; 32cm projectile caliber. | |

Antiaircraft guns and mortars will be discussed in detail in the second volume in this series, Battle Orders 14: The Japanese Army in World War II: South Pacific and New Guinea 1942–44. The principal AA weapons used by the IJA included:

13.2mm Type 93 (1933) machine gun

2cm Type 38 (1938) machine cannon

7.5cm Type 11 (1922) AA gun

7.5cm Type 88 (1928) AA gun

10cm Type 14 (1925) AA gun (actually 105mm)

Mortars included the 8cm (81mm) types 97 (1937) and 99 (1939); 9cm types 94 (1934) and 97 (1937); and 15cm types 93 (1933), 96 (1936) and 97 (1937). With the exception of the 9cm, these were of the common Stokes-Brandt design. These mortars were assigned to non-divisional mortar battalions (see Osprey New Vanguard 54: Infantry Mortars of World War II).

The diminutive Type 92 (1932) tankette was armed with a single 7.7mm Type 97 (1937) machine gun (removed here), based on the Czechoslovakian Brno design. It had replaced the 6.5mm Type 91 (1931). Fed by a 30-round magazine, it was the principal tank machine gun. The Type 94 (1934) tankette was identical in design to the Type 92, but had a much larger rear trailing idler wheel, and featured other suspension improvements.

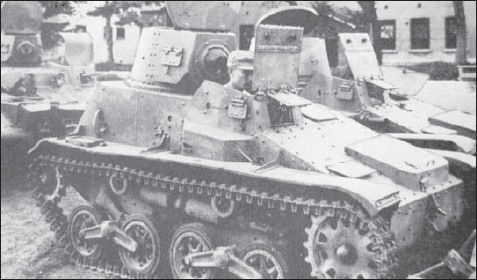

Japanese tanks, with most designs dating from the mid-1930s, were inferior to Western models encountered at the beginning of the war. They were very lightly armored, although the armor was of good quality. Their top speed was in the region of 25mph, but the obsolete Type 94 could only manage 20mph. All used diesel engines, but their mobility across rough terrain was somewhat limited. Accommodation was cramped for the medium tank’s four-man crew and even more so for the light tank’s three-man crew. No periscopes or bulletproof vision blocks were provided, only vision slits, making them vulnerable to small-arms fire. The 3.7cm gun on light tanks was suitable for knocking out pillboxes, as was the 5.7cm on medium tanks. Both were low-velocity weapons and ill suited for engaging enemy tanks. 7.7mm Type 97 (1937) machine guns were mounted in the hull bow and rear of the turret.

A Type 94 (1934) medium tank emerges from a streambed. This obsolete tank was still in use by the 7th Tank Regiment in the Philippines. The white insignia on the bow identified the regiment’s 2d Company. The Type 94 was similar in appearance to the Type 89A and B, but the driver’s and bow gunner’s positions were reversed.

The types 92 (1932) and 94 (1934) tankettes were used for reconnaissance, screening, liaison, and hauling supplies to forward positions. They were little use in direct combat. Both had a two-man crew and were sometimes provided with a small 0.75-ton capacity full-tracked trailer for the supply role. Japanese tanks employed in the Southern Operations included the following:

| Type | Armament | Weight |

| Type 94 (1934) medium tank | 5.7cm gun, 2 x 7.7mm MGs | 15 tons |

| Type 97 (1937) medium tank | 5.7cm gun, 2 x 7.7mm MGs | 15 tons |

| Type 95 (1935) light tank | 3.7cm gun, 2 x 7.7mm MGs | 10 tons |

| Type 92/94 (1932/1934) tankette | 1 x 7.7mm MG | 3.4 tons |

Type 94 (1934) tanks of the Sonoda Detachment churn forward as US–Filipino forces withdraw onto the Bataan Peninsula. The detachment consisted of both of the 14th Army’s tank regiments reinforced by a battalion of the 2d Formosa Infantry. A light machine gunner can be seen in the foreground.