The Physician’s Gun is a work of fiction, but it was inspired by a true event: the Maungatapu Murders, carried out by the ruthless Burgess gang. Descriptions of their evil deeds can be found in numerous books and newspaper articles. (See ‘References and Further Reading’ later in this book.)

A detailed account can be found on the New Zealand History website, but here is a summary:

On 12 June 1866, James Battle was murdered on the Maungatapu track, south-east of Nelson. The following day four other men were killed nearby – a crime that shocked the colony. These killings, the work of the ‘Burgess gang’, resembled something from the American ‘wild west’.

The case was made more intriguing by the fact that one of the gang, Joseph Sullivan, turned on his co-accused and provided the evidence that convicted them. The trial was followed with great interest, and sketches and accounts of the case were eagerly snapped up by the public. Unlike his colleagues, Sullivan escaped the gallows.

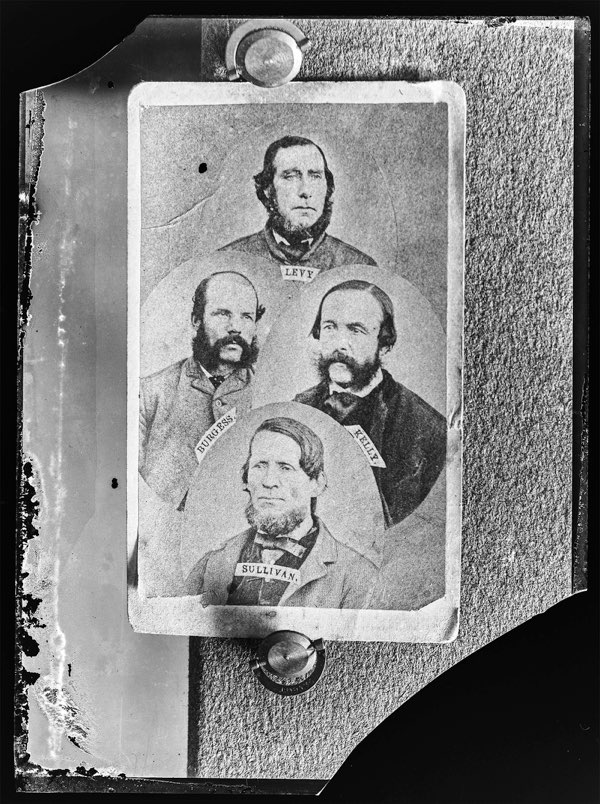

An early composite of the so-called Maungatapu Murderers: Philip Levy (top), Richard Burgess (left), Thomas Kelly (right) and Joseph Sullivan (bottom). (Maungatapu Murderers. Nelson Provincial Museum Collection: 319996)

All four members of the Burgess gang had come to New Zealand via the goldfields of Victoria, Australia. Three of them had been transported to Australia for crimes committed in England. They were the sort of ‘career criminals’ that the authorities in Otago had feared would arrive following the discovery of gold in the province.

The gang’s ringleader, originally known as Richard Hill, had been transported from London to Melbourne for theft at the age of sixteen. After his release he resumed a life of crime and served several prison terms. By 1861 he was calling himself Burgess, the name of a New South Wales runholder he had attempted to rob. In January 1862 he left Australia for the Otago goldfields, where he teamed up with Thomas Noon, an acquaintance from his prison days in Australia. They specialised in attacking and robbing lone prospectors.

In March 1862, members of the Otago Mounted Police tried to bring Burgess and Noon in for questioning over a robbery on the Otago goldfields. Gunfire broke out and the pair fled, but were eventually captured. They were sentenced to 3½ years’ hard labour in Dunedin Jail. After receiving thirty-six lashes for his role in another escape bid, Burgess vowed to exact revenge on society by taking a life for every lash.

On their release, Burgess and Noon (now calling himself Thomas Kelly) headed for the West Coast goldfields and staked a claim inland from Hokitika. Just before Christmas they carried out a series of robberies. Burgess was now living with a woman named Carrie who was pregnant with his child. His plan was to rob the bank at Ōkārito, south of Hokitika, and move back to Australia with her.

In the meantime, William (alias Philip) Levy arrived in Hokitika. He had emigrated to Victoria in the 1850s and established himself as a gold buyer. He also worked as a ‘fence’ (a seller of stolen goods) and passed on information about possible targets for robbery. In Hokitika he helped Burgess and Kelly plan robberies.

In April 1866 the gang was completed by another recent arrival from Victoria. Joseph Sullivan had been transported from England in 1840 for robbery, but by 1853 had established himself as a prize-fighter and publican.

On 28 May the gang murdered George Dobson, a surveyor whom they mistook for a gold buyer. Undeterred, they set up an ambush of the real gold buyer, but they were thwarted by the police and given 48 hours to leave town.

Using assumed names, Burgess, Sullivan and Kelly joined Levy aboard the Wallaby and departed for Westport with plans to rob the bank there. Finding that it had closed, they continued on to Nelson.

They arrived in Nelson nearly penniless on 6 June, and considered robbing one of the town’s three banks, but found the police presence too great. Instead, they decided to walk the 70 miles to Picton and try their luck there. They travelled via the rugged Maungatapu Track, which would take them past the Wakamarina goldfield.

On 10 June they arrived at the goldfields settlement of Canvas Town, 40 miles short of Picton. Levy set about finding a possible target for the gang. At nearby Deep Creek, he met Felix Mathieu, a publican and storekeeper. He and three associates, James Dudley, John Kempthorne and James de Pontius, were about to leave for the West Coast, carrying money and gold. When Levy informed the others, plans were made to ambush the travellers near the summit of the Maungatapu Track.

The gang left Canvas Town early on 12 June and were passed on the track by James Battle. Burgess and Sullivan, concerned about potential witnesses, throttled him and buried him in a shallow grave.

They attacked the Mathieu party on 13 June, killing them one by one. Dudley was strangled, Kempthorne and de Pontius were shot, and Mathieu was both shot and stabbed. The gang acquired cash and gold dust worth £320 (nearly $35,000 in today’s money).

The gang continued on to Nelson, where they booked into different hotels under false names. Next day they sold the gold and divided the proceeds equally before deciding to lie low for seven days, then travel to New Plymouth by ship.

Unbeknown to the gang, a friend of Mathieu’s suspected foul play when they failed to arrive in Nelson. He reported their disappearance to police, and when a search party found some evidence of a crime, Levy was arrested. On 19 June his three associates were located and arrested too.

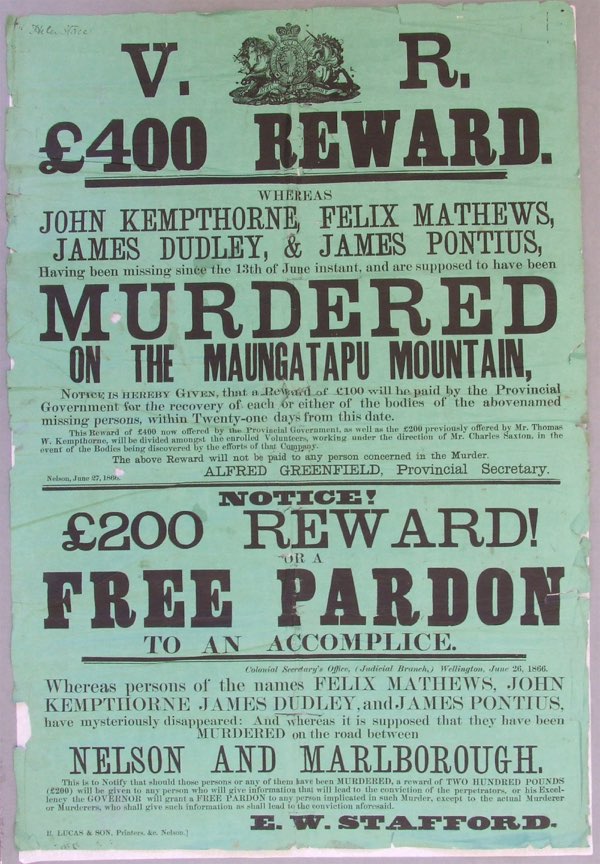

Without bodies, the police case was circumstantial. The government promised £200 (more than $21,000) and a free pardon to any accomplice (not the actual murderer) who turned Queen’s evidence, and Sullivan took the offer. He claimed to have been merely a lookout for the gang, and told the police about the killing of James Battle and incriminated the others. The bodies of Mathieu, Dudley, Kempthorne and de Pontius were recovered thanks to Sullivan’s evidence. Battle’s body was found three days later.

Awaiting trial, Burgess wrote a long statement – ‘The Confessions of Burgess the Murderer’ – in which he detailed his many crimes and exonerated Kelly and Levy.

The case went to the Supreme Court. A special sitting opened in Nelson on 12 September with Mr Justice Johnston of Wellington as trial judge.

In accordance with the terms of the amnesty, Sullivan was not charged. Burgess, conducting his own defence, was determined to implicate Sullivan directly in the killings and cross-examined him for 15 hours without success.

The judge spent more than six hours summing up the case for the jury. He described Burgess as an ‘arch plotter’, a ‘cruel assassin’ and ‘one of the wickedest of men’. The jury took less than an hour to find all three men guilty of murder. Kelly collapsed and was taken away sobbing, while Levy continued to maintain his innocence.

Members of the Nelson Volunteers surrounded the jail on the morning of the execution to ensure that ‘good order was maintained’. Before bounding up the scaffold steps, Burgess declared that ‘he had no more fear of death than he had of going to a wedding’. He selected the central noose and kissed it as ‘a prelude to heaven’. Kelly had to be carried up, while Levy calmly protested his innocence. There was a delay while the three condemned men made their final statements. Kelly was still speaking when – just before 8.30am – the hangman drew the bolt that opened the trapdoor.

Moulds for casts of the three heads were taken as a contribution to phrenology, a then-popular discipline that would eventually be dismissed as pseudo-science. Adherents of phrenology claimed that personal characteristics could be determined from the shape of an individual’s head.

The bodies were buried in the prison yard.

The full story:

https://

HISTORICAL PHOTOGRAPHS

Some extraordinary photographs from the 1860s – including portraits of the Burgess gang – can be found in the archives of our public libraries. A selection of these appear on the following pages. Studying old photos can provide useful information about the buildings, streets, clothes and hairstyles of the 1860s.

The author of The Physician’s Gun, John Evan Harris, inspecting the so-called ‘death masks’ of the three hanged highwaymen at the Nelson Provincial Museum. From left: Richard Burgess, Thomas Kelly and Philip Levy.

The Nelson Provincial Museum has a wonderful online collection, especially the Tyree Studio Collection. (Although many of these photos were taken in the 1870s, later than the 1866 setting of The Physician’s Gun, we can assume that clothing and street scenes did not change too much in those few years.) The museum also has 3800 negatives taken by William Davis during his time in Nelson.

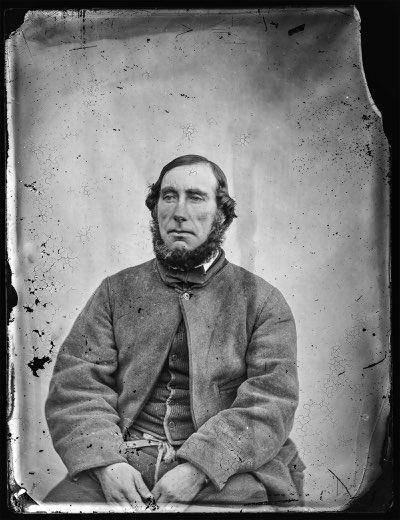

Richard Burgess

This is the only known image of Richard Burgess: a photo taken shortly after his arrest. He was charismatic, manipulative and complex. The writer Mark Twain remarked that Burgess’s ‘confession’ was “a remarkable paper… perhaps without its peer in the literature of murder.”

Born Richard Hill in 1829 in London, it’s believed Burgess was the illegitimate son of a ladies’ maid and possibly a member of the Horse Guards. His mother fell on hard times and young Richard became a pickpocket and then a housebreaker. He was jailed and then shipped off to Melbourne. He became a proficient stonemason but returned to a life of crime, and in 1852 was sentenced to 10 years for a robbery which he proclaimed he did not commit. He endured years of harsh punishment in Melbourne prisons and the notorious floating prison hulks. Hill changed his name to Burgess and came to New Zealand in 1862 where he was soon involved in violent robberies on the Otago goldfield. (Richard Burgess. Nelson Provincial Museum Collection: C1849)

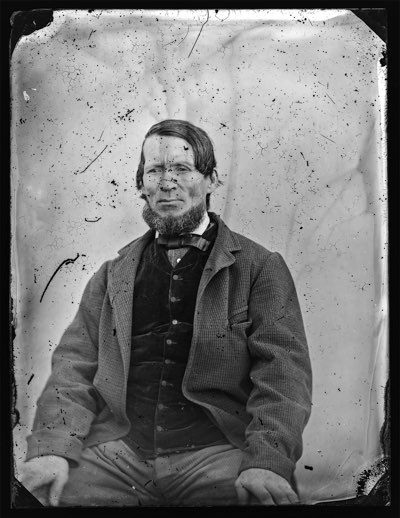

Joseph Thomas Sullivan

A photograph of Joseph Thomas Sullivan taken shortly after his arrest. Born in Ireland to Catholic parents, schooled in London, a boxer and baker, he was convicted of burglary aged around twenty-five and sent to Australia. He married and had two sons, and ran a public house for a decade in Victoria before coming to New Zealand in 1866. Sometimes referred to as ‘Flash Tom’, he managed to wriggle his way out of being put on trial with Burgess and the other gang members, but was promptly tried and found guilty of the murder of the flax-cutter James Battle. After serving a prison sentence in New Zealand he returned to Australia. He was widely loathed by the public not only because they thought he had been an active member of the Burgess gang but also because they believed he took part in the murder of the young surveyor George Dobson – for which he was never tried. (Mr Joseph Thomas Sullivan. Maungatapu Murderers’ Gang. Nelson Provincial Museum Collection: 318174)

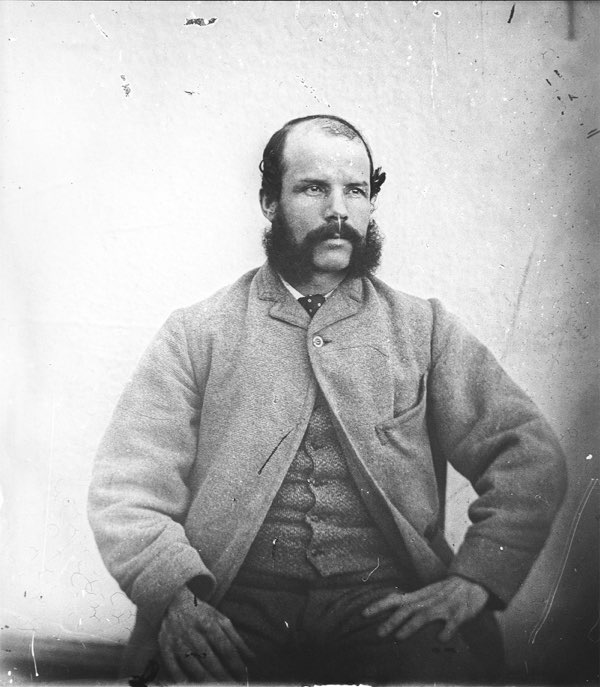

Thomas Kelly

A photograph of Thomas Kelly, taken shortly after his arrest. He was born Thomas Noon in London in 1825, to poor but respectable Catholic parents. After committing many petty thefts and burglary he was transported to Australia. He again took up a life of crime, which continued when he went to New Zealand and teamed up with Richard Burgess. (Thomas Kelly. Nelson Provincial Museum Collection: C1848).

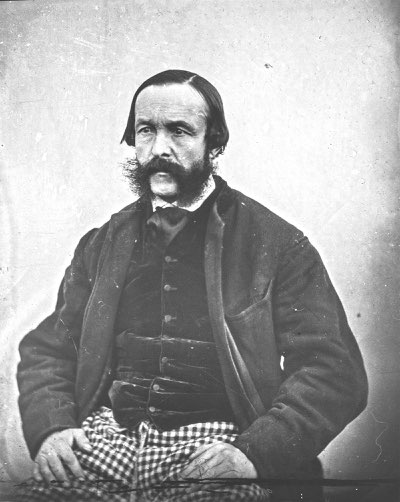

William Philip Levy

William Philip Levy was photographed along with the other members of the gang, shortly after their arrest. Born in London in 1831 to Jewish parents, Levy immigrated to Victoria as a free immigrant – unlike his fellow gang members. But although he set up as a general trader in the Otago goldfields he was suspected of being a ‘fence’ – selling stolen goods – and of helping criminals to identify potential targets for robbery. He was recruited by Burgess to do just that, and soon became an active member of the gang – although he went to the gallows professing his innocence. (Mr William Levy, Maungatapu Murderers gang. Nelson Provincial Museum Collection: 318110.)

When four businessmen went missing on Maungatapu Mountain, foul play was suspected. This poster was printed, and Joseph Sullivan, already under suspicion and languishing in prison, saw the offer of a free pardon for an accomplice and jumped at it. He became Queen’s Evidence and insisted at the trial of his accomplices that he did not take part in any actual murders. (Marlborough Museum, Marlborough Historical Society Collection 1994.040.0005)

Sergeant John Nash

Perhaps he does not look like the heroic law enforcement officer that Henry Appleton perceived him to be, but Sergeant John Nash was certainly a dedicated lawman. According to the NZ Police website, John Nash was born in Killarney, Ireland, about 1822. He sailed for New Zealand in 1845 with the 65th Regiment of the British Army. On leaving the Army in 1857 he joined the Nelson Provincial Armed Constabulary as a constable and was promoted to Sergeant in 1863. He was third in command of the Provincial Police Force in Nelson, and for his work in the hunt for the Burgess gang he was awarded a gold watch. Nash was registered as the first non-commissioned member of the newly formed New Zealand Police Force on 1 September, 1886. He had the number ‘1’ displayed prominently on his headgear. (Sergeant John Nash, July 1887. Nelson Provincial Museum, W E Brown Collection: 16898)

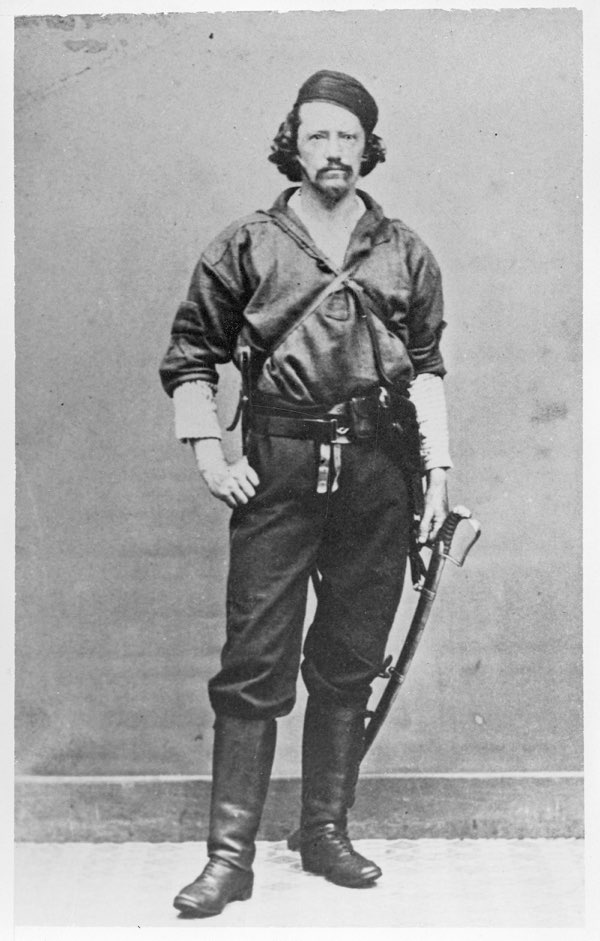

Gustavus Ferdinand von Tempsky

Gustavus Ferdinand von Tempsky became a folk hero in his brief but spectacular military career in New Zealand. He was born into a Prussian family with a long military tradition. After a brief time with the Royal Prussian Army, then digging unsuccessfully for gold in California and Australia, he sailed to New Zealand with his wife and young family in 1862.

On the Coromandel Peninsula he was a gold miner and newspaper correspondent but on the outbreak of war in 1863 he joined the Forest Rangers. They were an ‘irregular’ force intended to match the Māori who were skilled at fighting in the bush. As leader of his own company, he had large steel Bowie knives made for his men, and they used the short-barrelled Calisher and Terry .54 carbine, which was ideal for close quarter fighting. Von Tempsky himself carried two Colt Navy .36 pistols and was often pictured with a sabre which he carried unsheathed when expecting battle. Called “Von” by some of his men, he emerged as a very effective leader who inspired great loyalty. He was known to the Māori as Manurau, “the bird that flits everywhere”. The flamboyant and handsome Von Tempsky was also a talented amateur artist and singer.

But he was a self-publicist, described as being ‘avid for glory and admiration,’ and his impetuous nature led to his downfall. During a misguided and premature attack on Tītokowaru’s main fighting pā, he took one too many risks and was killed by a bullet through his forehead. He died aged only 40. (Gustavus Ferdinand von Tempsky. Making New Zealand: Negatives and prints from the Making New Zealand Centennial collection. Ref: MNZ-0876-1/4-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand https://

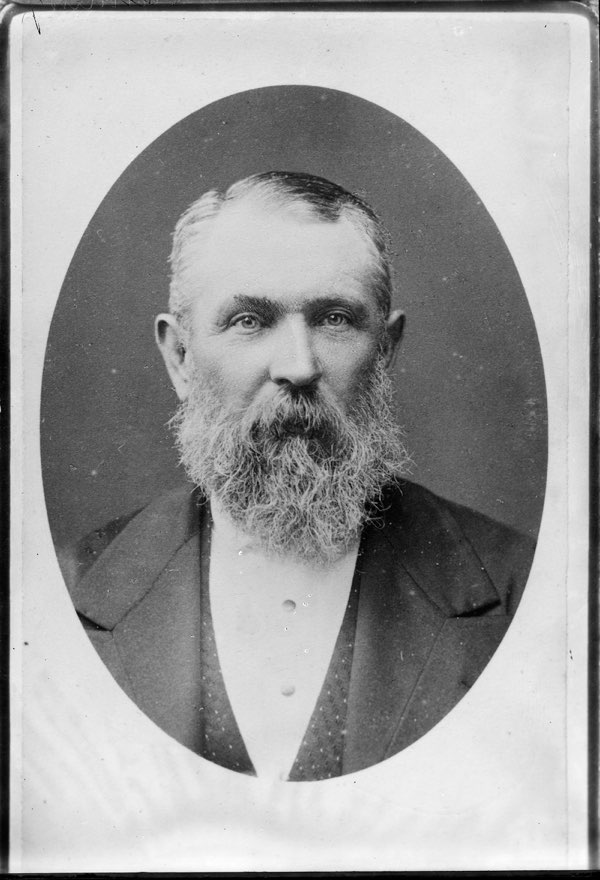

Charles Canning. Nelson Provincial Museum, Tyree Studio Collection: 67863.

This is Charles Canning, a prominent Nelson farmer and businessman who was foreman of the special jury at the trial of the Maungatapu murderers. He was a benefactor who donated or sold land for various community activities, at one stage held the important role of Chief Inspector of Sheep, and was well known for planting a large number of trees in the district. He married Catherine Jane McRae in 1862 and they had two children – Elizabeth Sarah and William Davis. Because his son was ill he took his family back to England in 1884, and he died in Somerset in 1892 at the age of 64.

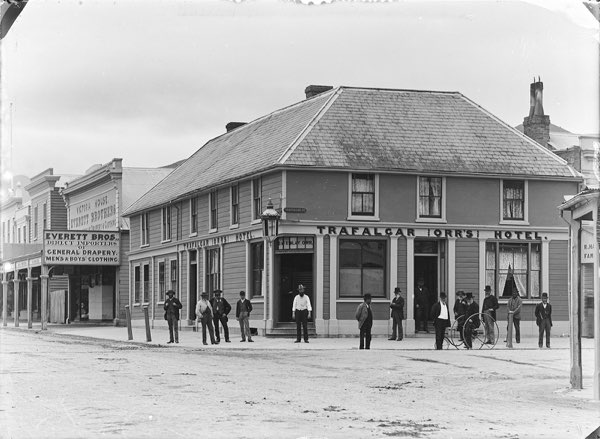

Trafalgar Street, circa 1863. Nelson Provincial Museum, Kingsford Collection: half 743.

This photograph gives us a good idea of what Nelson looked like when Richard Burgess and his gang came to town after their murderous exploits on Maungatapu Mountain. The photo was taken in 1863, just three years before the murders, looking south up Trafalgar Street to Church Hill and the Cathedral. To the left of the cathedral are several buildings, possibly including the Court House and jail.

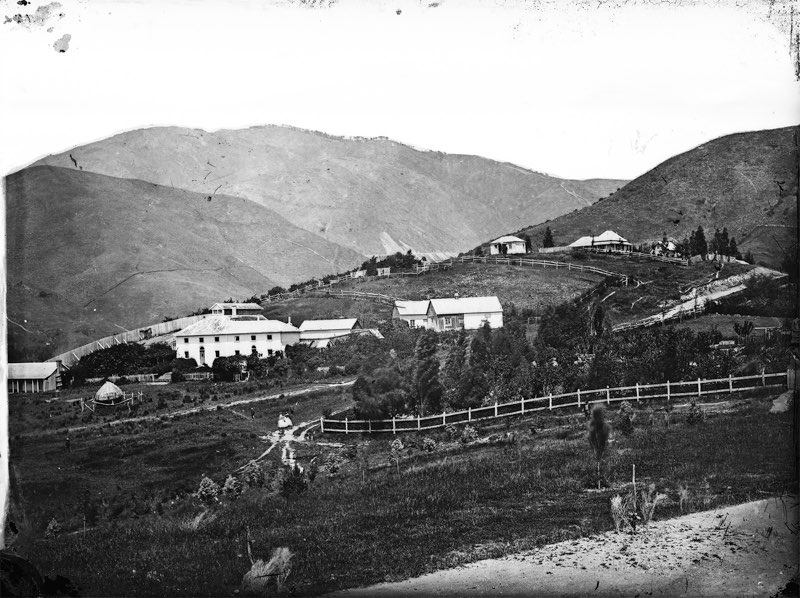

Nelson foothills, 1860s. Nelson Provincial Museum, Kingsford Collection: 156001.

This photograph, taken in the Nelson foothills in Burgess’s time, shows the area was still sparsely-occupied by settlers. But the European influences are plain to see in the design of houses and fences, and the rather unsuitable clothing they insisted on wearing. (Note the long dresses of the two women at the lower end of the fence line!) Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the scene is the lack of native bush and forest: most of the majestic trees have already been felled for timber for houses and other buildings, and for ships’ masts, railway sleepers, fence posts, furniture and export. And firewood.

Trafalgar Hotel. Nelson Provincial Museum, Tyree Studio Collection: 34911.

The Trafalgar Hotel, one of many in the district, stood prominently at the corner of Trafalgar and Bridge Streets.

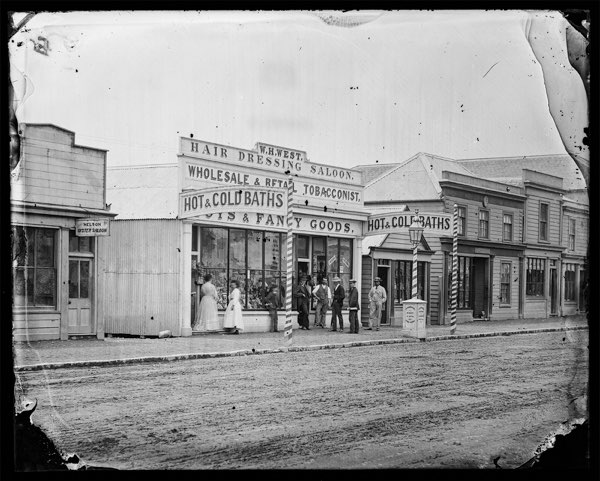

West’s Shop. Nelson Provincial Museum, Davis Collection: 10279

W.H. West’s Saloon and Tobacconist in Hardy Street, where many of Nelson’s menfolk would go for a haircut and shave, to read the newspapers, and to chat. The shop sold toys, fireworks, gun powder and shot for firearms. It also offered hot and cold baths.