Joseph Sullivan cracked his knuckles.

“Surprise!” he leered, exposing his rows of rotten teeth. He jumped at Henry’s mother and wrapped a sinewy arm around her neck.

Henry cried out, “No!”

“Hear the little rooster crow!” Sullivan raised one large fist and knocked Henry to the floor.

Henry saw stars. A pain shot up his jaw.

“That’s for interferin’.” Sullivan pressed a large boot against Henry. “I seen youse in town tonight, ya little runt.”

Henry lay on the floor, half-conscious. Sullivan’s punch had split the skin on his jaw, and it began to bleed. Sullivan prodded him in the ribs with his boot. “Get us the keys for the bank, like Burgess said. Or else.”

He pushed Henry’s mother out the door. “You’re coming with me, lassie.” She looked back at her injured son.

“Henry!”

They disappeared into the darkness.

Henry struggled to get to his feet. “Mother!”

“Just get the keys, punk!” Sullivan yelled from the darkness.

Henry staggered to the door, holding his jaw, and peered out into the night. He began to follow them, then reconsidered. He shouted, “Don’t hurt her! I’ll get the keys.” Somehow. He closed the front door, and avoided looking at his father’s photo on the wall.

I’ve got to get help. He waited just inside the door, trying to think of a plan. My head…

He opened the door a crack. He could see nothing, but the voices carried in the cool night air.

Burgess was out there under the trees. “You shouldna done that, Sullivan,” he growled.

“I don’t trust that little toad,” said Sullivan.

Henry heard his mother say something, and Burgess snapped, “Don’t ’arm the woman.”

“Aye aye, yer majesty,” sneered Sullivan. “Wouldn’t dream ov it.”

There was the rustling of movement in the bushes. “Move aside, Kelly,” said Sullivan.

The sounds receded. Henry leant towards the blackness and listened. Have they all gone?

Then Kelly spoke. “You reckon the lad’ll do it?”

“Get the keys?” replied Burgess. “Course he will. He’s one ’elluva scared kid. C’mon.”

A scared kid? Henry bristled. You wait and see. He heard Burgess and Kelly follow Sullivan into the forest, then shut the door.

He carried the lantern into his bedroom, set it down, then slumped against the wall. He touched his jaw and winced.

He was a frightened kid, all right. And his head hurt. And his backside. He crawled into the lounge… and collapsed.

He dreamt a scene from Masters of the Prairie. He was riding Duke across the wide open spaces, firing his gun in the air, chasing … or was he being chased? The dream abruptly became a nightmare as he found himself being manhandled by Burgess and Sullivan. Running through the forest. Falling. Being shot. Running again. Burgess’s leering face: “I’m yer farver.”

He snapped awake. There were birds singing. Dawn light flickered through the window onto his face. He moaned.

I hurt all over. He pushed himself onto his knees, painfully, and peered out.

It was not yet fully light. The leaves in the trees barely stirred. Duke was standing near the cottage, asleep. I need to get help. Henry crawled into the kitchen, glanced at his father’s photo – Help me, Father – and picked three carrots from the vegetable basket.

Keeping low, he crawled to the back door. Outside, he crept to the corner of the cottage, where he could see Duke. He broke off a piece of carrot and hurled it at the horse. It fell short. He got another piece and flung it harder.

PIT! The carrot hit Duke. The horse snorted. He saw the carrot and sniffed it. Chomped it. Henry waved his arms. Duke looked at him, then resumed munching.

Come here, you stupid horse! He waved a piece of carrot in the air. Duke ambled towards him. That’s right, this way. Henry held out the carrot. Duke took it and munched noisily.

Henry slipped a rope over Duke’s neck and led him around the back of the cottage, where they couldn’t be seen from the woods. Still on foot, he reached the next field, hidden by the barn. Only then did he risk scrambling onto Duke’s back.

We’ve made it.

He rode Duke bareback, hanging onto his mane and the rope. They walked at a slow pace. Henry realised he was trembling with anxiety, but he had a new focus. Henry Appleton to the rescue! He did not dare to think about his mother. She has to be safe. Please.

He had no idea where Burgess and his gang might be hiding, so he made as little noise as possible. Duke seemed to understand, and trod lightly along the rough track through the forest.

There was an occasional whoo whoo from a ruru about to go to sleep. Other birds were already awake and busy – the kākāriki, pīwakawaka, tūi – even in this moment of intense fear, he found himself trying to recall their Māori names.

Their screeching, trilling, twittering, wheezing, coughing, cackling and chirping was almost deafening.

Henry and Duke entered Pritchard’s Glade. It was deserted as always, and Henry tried to avoid the black eye sockets of the cottage’s empty windows. He kicked his horse into a trot.

His father’s headstone was prominent even in the meagre dawn light, but Henry did not look at it as he trotted past. I must get help.

As the sun emerged from the horizon the bright chatter of the birds built to an ear-shattering crescendo. Their warbling was relentlessly cheerful. If only they knew!

Henry and Duke galloped on.

Most of Nelson was still asleep when they trotted into town.

It was June 13, 1866.

A lone shopkeeper was sweeping his porch. Henry paid no attention to him, nor to the man sprawled on the sidewalk, hat pulled low. The man watched Henry leap from his horse and run into the hotel.

Henry rapped on the door to Doctor Smith’s room. The doctor opened it, holding a shaving cloth to his chin. Miriama appeared behind him, once more disguised as a man.

Miriama. Her face was sad, but she smiled when she saw Henry.

Henry pushed past Smith, gasping. “They’ve taken my mother!” He collapsed into a chair. “Burgess and Sullivan. They told me to get the keys to the bank. If I don’t, they’ll kill her.”

He buried his face in his hands. “What can I do? They’re going to kill her if I tell the sergeant.”

Smith placed a hand on Henry’s shoulder. “These men must be stopped.”

He paused. Then, “Miriama, give Henry your room key.”

While she looked for her key, Smith hauled a bag from underneath his bed and took out an object wrapped in cloth. Despite his anguish, Henry watched with interest.

Miriama handed Henry a large door key.

“Henry,” said Smith, “take this key to Burgess. Tell him it’s for the back door to the bank.”

“But he’ll find out!” Henry protested.

“They won’t go to the bank till nightfall,” Smith replied. “That gives me plenty of time to find them.”

What? “You’re going to look for them?” What about my mother?

He was distracted when Smith unwrapped the cloth bundle and pulled out a pair of Tranter revolvers.

The best! Henry was impressed; especially when he saw the guns had pearl handles. Johnny Slick had described a pair in his Civil War novel Gunfight on the High Plateau. Why would a respectable doctor have guns with pearl handles? So flashy!

Smith shoved a box of cartridges into the pouch on his belt. “I’ll start at Pritchard’s Glade,” he said.

“But when they see you –”

“Henry, stop ‘but-but-butting’. I’m an experienced marksman. They’re clumsy thugs.”

“But there’re four of them. I’ll come with you.” I’m not a boy anymore.

“No. That would give the game away.”

“What if they kill you?”

“Then you’ll make sure the sergeant is waiting for them in the bank.” Abruptly, Smith left the room.

Miriama and Henry sat silently for a long moment. They heard the doctor’s footsteps retreating down the stairs.

Henry’s head was spinning. It’s too dangerous! “I don’t like it.”

Miriama squeezed his hand.

The streets of Nelson were still quite empty as Smith rode out of the lane from the stables. He was about to set off when Henry rushed out.

“Doctor Smith – please wait!”

“I’ve waited too long, Henry.”

Henry stood in front of Smith and his horse. “I’m worried about my mother.”

“I’m aware of that. Please move.”

Henry hung onto the horse’s bit. He didn’t know what else to do. The horse shied. “Your wife’s already dead,” Henry cried. “I don’t want my mother to die too.”

Smith’s face was flushed. “Let go, boy!’ He slapped his whip on Henry’s shoulder. Henry yelped, and released the bit. Smith charged off.

Miriama ran out. “Henry!” She pulled back his collar to see the red welt left by Smith’s whip.

Henry scrambled to his feet. “We’ve got to stop him!”

He was about to untie Duke when an exciting thought struck him. The rifle!

Henry was about to untie Duke when an exciting thought struck him. “I need a gun!” he told Miriama.

He bounded up the stairs into Smith’s room. The physician’s Calisher and Terry was where he’d seen him put it, in the corner next to the wardrobe. He grabbed it and took a box of paper cartridges from the top of the wardrobe. This is stealing – but I’ve got to have a gun!

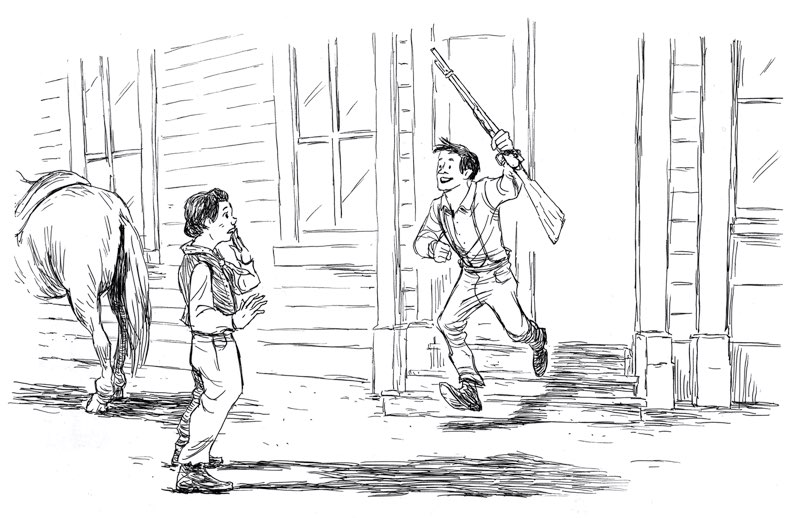

He raced back down the stairs. Miriama’s hand went to her mouth when she saw the rifle, but she said nothing.

“I need a gun!” said Henry. As he untied Duke, he told Miriama, “Find the sergeant! Please! Tell him what’s happening.”

He jumped onto Duke and galloped after Smith. Miriama watched him go, then headed for the side door. She paid no attention to the bedraggled man still sprawled on the footpath. He got up, cracked his knuckles, and followed her.

As Miriama reached for the door handle, a huge arm wrapped around her.

“You’re not going nowhere, sonny,” Sullivan grunted.

Miriama cried out. Her hands clawed at Sullivan’s jacket. She stamped on his foot and smashed an elbow into his midriff.

Many men would have buckled under Miriama’s determined blows. But Sullivan roared like a bull and brought down the handle of his knife on Miriama’s head.

She crumpled.