Duke and Henry galloped across the open space, past the chapel, and came to a stop at the cemetery.

Henry’s mind was swirling with sounds and images of the hanging. He had just seen Richard Burgess die a grisly death, and now he knew where he wanted to go. Where he needed to go. He stopped by the grave of William Henry Appleton, the man who had raised him and passed on his values.

William Appleton may not have been his birth father, but he was the man who had given Henry the love and security he needed.

I want to be like you, Father, not like Burgess. He slumped in the saddle. Why did Burgess have to come into my life?

He rested his head on Duke’s neck and thought about his last visit with Burgess in prison. The man had pleaded with him to call him ‘father’, but he couldn’t. And he had made him a gift.

The gift! Henry remembered the parchment, still folded in his pocket. He wiped his eyes, unfurled it, and squinted to read the intricate handwriting:

Ecclesiastes chapter 9, verse 10: “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do –”

As he read it, he could hear the voice of Burgess:

“… do it wiv thy might, for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom in the grave wither thou goest.”

Henry puzzled the relevance. Why did Burgess write this? He heard Burgess’s voice as he resumed reading.

“He that loveth silver shall not be satisfied wiv silver. Instead shall thou find great treasure beneath the tree where first thy life was spared.”

Henry stiffened. These words are not from the Bible. He looked again. Beneath the tree? The drawing alongside the text showed a figure digging beneath a tree. Nearby, another figure was sprawled on the ground.

That’s me! A horse. That’s Duke! And an egg. That’s where Burgess jumped out at me.

The truth dawned on him like a slap in the face, and he laughed out loud. “Of course!” He reached down and grabbed the handle of a shovel stuck in the earth near his father’s grave. A phrase caught his eye:

Learn to do good; seek justice.

He galloped off and plunged into the dark forest, slowing only to navigate the twisted undergrowth. Here was the track where the ghosts of Burgess and Sullivan had pursued him.

Was it only a few months ago?

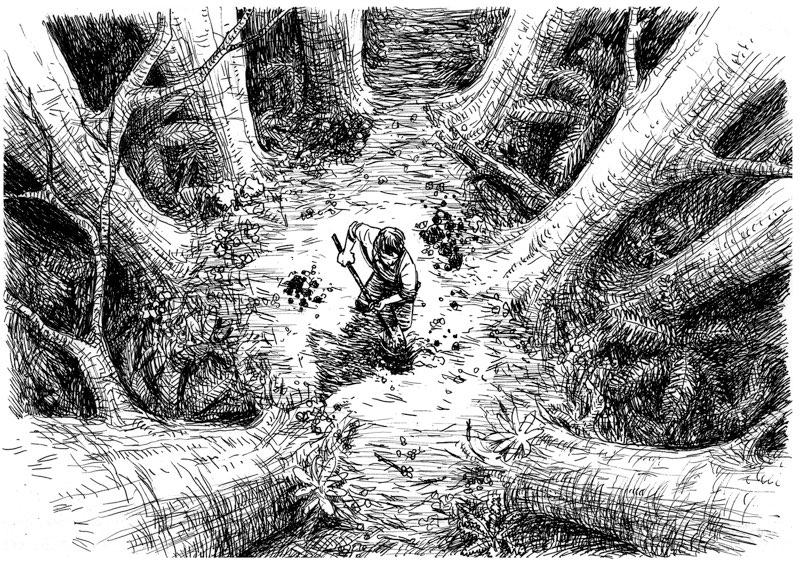

Finally, he came to the spot where Burgess had ambushed him. He slithered from the saddle and saw a dead shrub at the base of the tree. He tossed it aside. The soil was freshly turned. This must be it. He stabbed at it with the shovel. He half-knelt, awkward with his stiff leg. Scraped soil away. It was hard work.

“Treasure of great worth”? What could it be?

He glanced above and about him: it seemed the giant trees were staring down at him. What are you looking at? He continued to scoop out the earth and throw it aside. Feverish now. His leg was aching, but he could not stop.

“Thou shall find great treasure beneath the tree where first thy life was spared.” Henry could hardly breathe with excitement.

Finally, success: he dragged out a box.

“Yes!” This is it! He could hardly breathe with excitement as he wrenched the box open. Inside was a small sack tied with a cord. With shaking hands, he pulled it open.

There, lying before him, was a small pile of gold nuggets.

Treasure!

Some nuggets were no bigger than a pea, but many were the size of a walnut.

They resembled bits of crumpled volcanic rock, except for their telltale dull yellow colouring. Soon they would be cleaned and polished and fashioned into precious bars or jewellery.

Henry scooped up a handful. I’m rich!

He shouted in the air, “Thank you, Burgess! Thank you, God!”

I can buy the farm!

Henry paused to glower at the trees that crowded above him. Then he allowed the nuggets to tumble from his fingers, glinting in the sun, and back into the sack. He tied the cord at the neck of the sack and threw it over Duke’s saddle.