Stalin’s Falcons Decapitated

Ironically, in the year preceding Hitler’s invasion, as the Red Air Force’s numerical strength grew its effectiveness declined. This was in part due to its loss of technical parity with other European air forces, as well as the setbacks it experienced in Spain during the Spanish Civil War and in the Winter War with Finland. The Red Air Force was slow to learn from these hard-won lessons and in common with the Red Army suffered thanks to the destruction of its high command by Stalin.

The Red Air Force was not immune to Stalin’s purges during the late 1930s. General Ya. I. Alksnis, Red Air Force Commander-in-Chief, and General A.I. Sedyakin, Air Defence Commander-in-Chief, were shot during the Soviet leader’s paranoid bloodletting. The execution of the former Red Air Force commander, General Ya. V. Smushkevich, occurred four months after the German invasion, Smushkevich having been dismissed in 1940. His replacement, Pavel Rychagov, lost his job in the spring of 1941 to Pavel Zhigarev. According to German intelligence the actual strength of the air force prior to the invasion was about 30 per cent less than the authorized establishment. Stalin’s air force, like the rest of the Soviet armed forces, was not in the best condition to fend off Hitler’s blitzkrieg.

Stalin, who was almost the architect of his own destruction, did all he could to derail the modernization of the Red Air Force. Alksnis’ crime was being too closely associated with the discredited modernizer Marshal Tukhachevsky. He was on his way to a diplomatic reception in Moscow when, on 23 November 1937, he was grabbed and whisked away to the Lubyanka prison: he was dead in less than year.

Alksnis was not alone; most of his comrades suffered the same fate, including Chief of the Air Staff and Head of the Special Purpose Air Arm Vasily Khripin, Head of the Air Force Political Directorate B.U. Troyanker, and Head of the Zhukovsky Air Force Academy General A.I. Todorski, along with five military district air commanders. Only a year before, these men had received decorations from Stalin himself.

Alksnis’ initial replacement did not prove up to the job and was replaced by the highly experienced Smushkevich ready for the invasion of Eastern Poland in 1939. Under the nom de guerre General Douglas, Brigade Commander Yakov Vladimirovich Smushkevich commanded the Soviet Air Group in Spain known as Stalin’s Falcons. They combat tested the Soviet Union’s I-15 and I-16 fighters as well as the SB-2 bomber. Smushkevich then went on to command the Red Air Force, supporting General Georgy Zhukov’s brief and highly successful border war against the Japanese on the Mongolian–Manchurian border. Smushkevich was unable to repeat his Manchurian successes over Finland and the poor condition of the Red Air Force was highlighted during the Winter War, which broke out in November 1939 and was fought through three and a half months of freezing weather.

Smushkevich had 900 aircraft available for operations against less than 100 Finnish planes. Nonetheless, they suffered heavy losses, especially the obsolescent SB, DB-3 and TB-3 bombers. Large-scale Soviet bombing raids failed to achieve much and ground support was poorly coordinated. By the time the war with the Finns came to an end the Red Air Force had massed 2,000 aircraft against Finland. Despite much backslapping the Soviets lost up to 950 aircraft whilst the Finns lost just seventy. It was a hard-won victory that showed the Red Air Force to be a largely flawed instrument.

In April 1940 Smushkevich was sacked and replaced by his former brother-in-arms Pavel Rychagov. He was another of Stalin’s Falcons, credited with fifteen victories in Spain and named as a Hero of the Soviet Union. Rychagov also saw action against the Japanese in Manchuria. Commissioned as a fighter pilot in Ukraine, he rose in four short years from squadron leader to head of the Red Air Force, only to be swept away in Stalin’s purges barely two months before Hitler’s invasion. He lasted until the spring of 1941, to be replaced by Pavel Zhigarev (another commander from the Soviet Far East) in what must have felt like an unending game of deadly musical chairs. Smushkevich was shot on 28 October 1941, depriving the Red Air Force of his valuable expertise.

The Soviet aircraft industry suffered as well; A.N. Tupolev, head of the Experimental Aircraft Design Section, was arrested on the ludicrous charge of having sold the plans for the Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighters to Germany! His senior design team, including Vladimir Petlyakov and Vladimir Myasishchev, soon joined him. An estimated 450 designers and engineers were interned from 1934 to 1941. Of these, fifty were executed and 100 died in the Gulag.

At the same time, many of the aircraft factories lost key personnel, including directors, chief engineers and designers. The failures of prototypes to meet performance criteria and accidents during test flights were considered deliberate sabotage. When Valery Chkalov was killed in the prototype I-180 fighter on 15 December 1938, the death of this national hero led to a wave of arrests despite the accident being down to pilot error. This fighter was abandoned shortly afterwards, depriving the Red Air Force of 3,000 I-180s that would have been in service by June 1941.

The Soviet armed forces were divided into five elements prior to the Second World War: the ground forces, navy, air force, national air defence and armed forces support. The ground forces accounted for the largest proportion of personnel, with just over 79 per cent. The Red Air Force had just over 11 per cent and the navy had just under 6 per cent. The Red Air Force consisted of four key elements: the Voenno-Vozdushnye Sily (VVS – Air Force), Protivovozdushnaya Oborona (PVO – Air Defence), the Fleet Air Force and Gosudarstvenny Komitet Oborony (GKO – State Committee for Defence) Air Reserve.

The Soviet Union claimed to have the world’s largest air force in 1940, but in reality 75 per cent of them were obsolete I-15, I-152 and I-153 biplanes and I-16 monoplanes. Whilst the I-16 was the best, it was significantly inferior to the German Bf 109E. Their new LaGG-3, MiG-3 and Yak-1 had yet to be issued in any number although by 22 June 1941, about 2,030 of these aircraft had been produced.

Initially, a Soviet fighter regiment consisted of three squadrons with an established strength of forty aircraft. These squadrons flew tight defensive formations with three or four aircraft known as Zveno. A fighter aviation division was made up of three regiments, with a nominal strength of 120 aircraft. These divisions were grouped in two or threes to create aviation army corps with strength of up to 375 fighters.

At the outbreak of the war the mainstay of the Red Air Force’s fighter squadrons were aircraft designed by Nikolai N. Polikarpov. The Polikarpov I-16 was first flown in late December 1933 and was the first production monoplane in the world to feature a retractable undercarriage. It was also the first Soviet fighter to incorporate armour plating around the cockpit. Introduced into service in 1934, this aircraft had a number of major design faults; most notably, the engine was too close to the centre of gravity and the cockpit was too far back. This gave the airframe insufficient longitudinal stability, making it impossible to fly ‘hands off’.

Taking off and landing was not pilot friendly, either. The pilot had to hand crank the undercarriage forty-four times before retraction was complete. When deployed the undercarriage suspension was hard, which meant the aircraft had a habit of bouncing violently when it ran over uneven ground. This gained it the nickname Ishak (donkey). Nonetheless, in the hands of an experienced pilot the I-16 proved to be highly manoeuvrable. The I-16 saw combat in Spain with Stalin’s Falcons against the Spanish Republicans and against the Japanese in the Far East. The Spanish Nationalist Air Force christened it the Rata (rat). This nickname stuck and was used by the Luftwaffe.

Despite its shortcomings, by the time production ceased in 1940 some 6,555 I-16s had been built. Variants included the TsKB-18 assault aircraft armed with four PV-1 synchronized machine guns, two wing-mounted machine guns and 100kg of bombs. The Type 17 featured two wing-mounted cannon and this variant was built in large numbers. The TskB-12P was the first aircraft in the world to be armed with two synchronized cannon firing through the propeller arc. The last fighter version the Type 24 was capable of a top speed of 523km/h (325mph).

The Polikarpov I-153 was first flown in 1938 and was derived from the I-15 biplane fighter. The latter had featured a gull-type upper wing, while the following variant, the I-15bis (or I-152) was fitted with a straight wing. The I-153 reverted to the gull wing arrangement, resulting in it being dubbed the Chaika (seagull). Unlike its predecessor it featured a retractable undercarriage. A series of engine upgrades eventually gave the Chaika a top speed of 426km/h (265mp).

The pilot sat in an open cockpit with only a small windscreen for protection. The aircraft was armed with four synchronized machine guns firing along canals between the engine cylinders. A few were also fitted with two 20mm cannon. The Chaika first saw action in 1939 against the Japanese. It was also heavily involved in the Winter War of 1939–40, when the Soviet Union clashed with Finland. The I-153 was simply too slow against the Luftwaffe and was the last single-seat fighter biplane built in the Soviet Union.

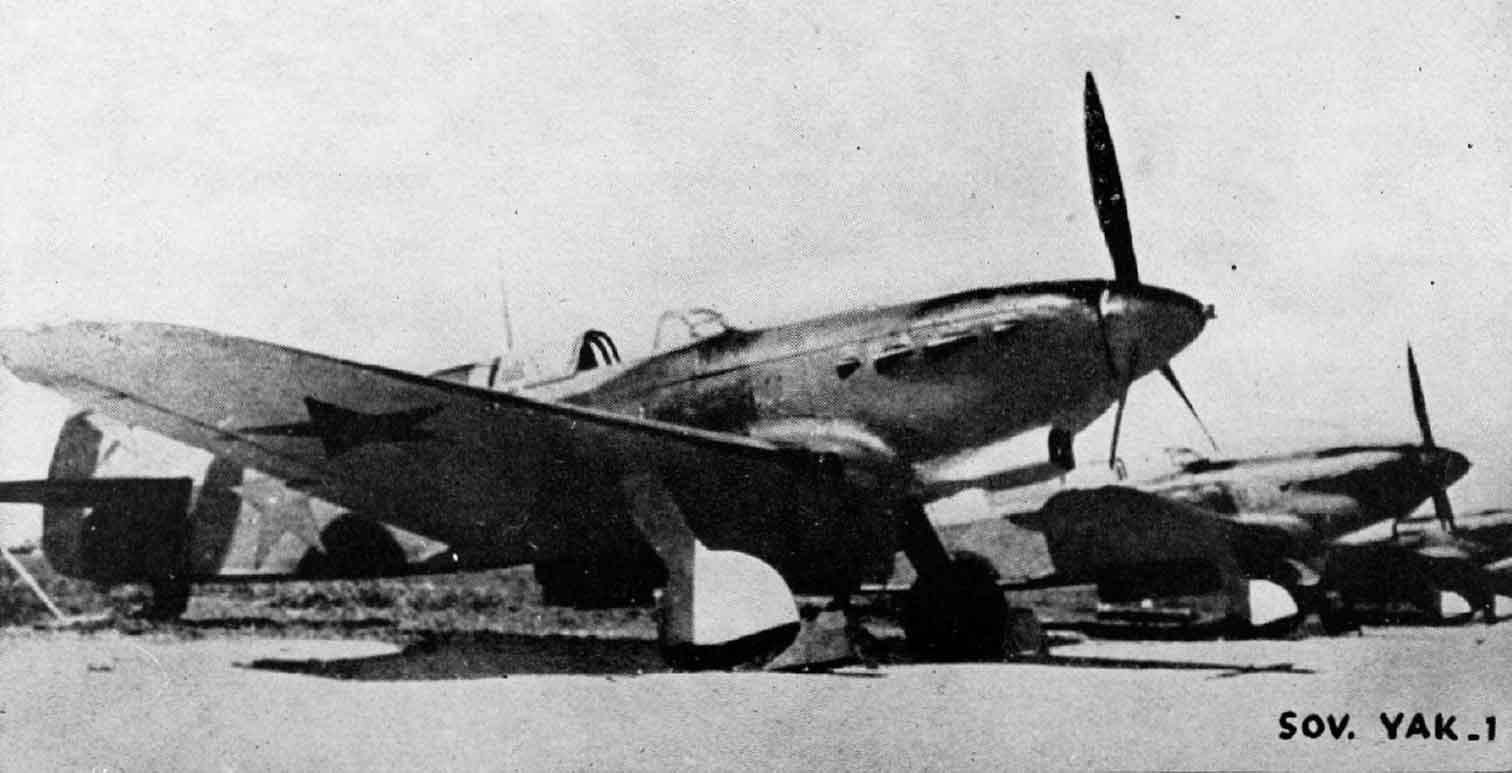

The Soviets were late in developing an effective monoplane in the same class as the British Hurricane and Spitfire and the German Bf 109. The Yak fighter sought to address this shortcoming. The Yak-1 Krasavyets (beauty) first appeared publicly on 7 November 1940. This was Aleksandr S. Yakovlev’s very first fighter design, powered by a 746KW (1,000hp) M-105PA engine armed with a nose-mounted 20mm cannon and two machine guns. This was a crude aircraft; there were no flying blind instruments and no fuel gauges! The gunsight was rudimentary, as was the cockpit equipment. Visibility was poor thanks to the four-piece cockpit canopy. Capable of 600km/h (373mph), it was reportedly a pleasure to fly and easy to maintain. Unfortunately, the German invasion disrupted production while the aviation factories were evacuated.

As a wartime expedient it was decided to convert the two-seat trainer variant, the Yak-7V, into a single-seat fighter by covering the second cockpit. This aircraft was redesignated the Yak-7A, but during 1942 the basic Yak-1 evolved into the slightly improved Yak-1M with a three-piece sliding hood, revised rear fuselage and smaller wing area. Likewise, the Yak-7A was upgraded to the Yak-7B, of which 6,399 were produced. Refinements to the Yak-1M before the aircraft entered quantity production in early 1943 led to the Yak-3. Some of these were heavily armed; for example, the Yak-3K was equipped with a 45mm cannon and the Yak-3T with a 37mm cannon. Another variant, the Yak-9, which was a further development of the Yak-7, entered service in 1942 and became the most mass-produced Soviet fighter.

In late 1939, the design bureau of Artem I. Mikoyan and Mikhail I. Guryevich was ordered to come up with a single-seat, single-engine monoplane interceptor. Within four months they had produced a prototype, which went into production as the MiG-1. Whilst the aircraft had a high performance, this came at a price, with armament being sacrificed in favour of a heavy, high-altitude engine that gave it a speed of 640km/h (398mph).

The MiG-1 was handicapped by the length of its engine, which resulted in poor pitch and directional stability. In addition, following Russian tradition the pilot had to endure high altitudes and high speed in an open cockpit. Despite being difficult to fly and unstable it was rushed into production. The weight of the engine meant that it could only carry one nose-mounted 12.7mm machine gun and two 7.62mm machine guns in the wings. After the first 100 MiG-1s had been built the aircraft was improved and redesignated the MiG-3. This featured a fully enclosed cockpit and an auxiliary fuel tank. Its increased range led to the MiG-3 being employed for fighter reconnaissance roles.

The MiG was needed as a matter of urgency to arm the fighter regiments of the Air Defence Force (PVO) created in early 1941 and by the end of June 1941, 1,309 MiGs had been produced compared to 399 Yak-1 and 322 LaGG fighters. The MiG-3 was the most prolific of the three new types of fighter at the outbreak of war. From equipping just 10 per cent of the front-line force in mid-1941, this rose to 41 per cent by the end of the year.

The MiG-3’s ability at high altitude made it a good tactical reconnaissance aircraft, but at low to medium altitude it was no match for the Bf 109E/F. During the Battle of Moscow the MiG-3 was also used as a night fighter. Despite attempts to improve them, MiG fighters were never a match for the Lavochkin or Yakovlev designs.

The LaGG-3 was one of the most modern fighter aircraft available to the Red Air Force at the time of the German invasion, having just come into service in early 1941. Designed by Semyon A. Lavochkin, the LaGG-3, although well armed with a 20mm cannon and two machine guns, proved to be heavy – slower than the MiG or Yak and hard to control. As a result it was very unpopular with pilots. Whilst the LaGG-3 had similar armament to the Bf 109, crucially it was slower, heavier and much less manoeuvrable. Some 6,528 LaGG-3s had been produced by 1944, before production in Tbilisi had been switched to the Yak-3.

The vastly improved Lavochkin LaGG-3 – known as the La-5 – did not enter service until July 1942 and was followed by the La-7 in 1944. These acted as low- and medium-level fighters. They were also sometimes used in a ground-attack role. Production of the La-5/La-7 series amounted to 21,975 aircraft by the end of the war.

Confident looking Red Air Force pilots photographed in 1939 during the fighting in Mongolia against the Japanese. Stalin’s Falcons gained valuable combat experience fighting in Spain, Finland and Mongolia during the late 1930s. Behind them is a Polikarpov I-16 fighter.

[Top, Above] The Polikarpov I-16 was initially flown on 31 December 1933. It was the first production monoplane to have a retractable undercarriage and was the first Soviet fighter to have armoured plating protecting the pilot. At the time of the German invasion it provided the mainstay of the Red Air Forces’ fighter squadrons. Both these aircraft appear to have suffered violent crash-landings before falling into German hands. It is also conceivable that the second aircraft was caught on the ground by the Luftwaffe’s opening assault on the Soviet Union, although the dent to the lower part of the engine cover indicates it made a nose-down landing.

[Top, Above] Two views of the two-seat training version of the I-16, known as the UTI (there were three models, known as the UTI-1, UTI-2 and UTI-4, based on the Type 1 and Type 5 I-16). These are the UTI-4, which featured fixed landing gear, making them slightly easier to handle. About 3,400 of these were produced; they became scrap after the German invasion.

The Polikarpov I-153 biplane fighter was first flown in 1938 and features a very distinctive gull-shaped upper wing; this gained it the nickname Chaika (seagull). This wing also featured on the I-15, but unlike its predecessor the I-153 had retractable landing gear. This aircraft seems to have been shot up on the ground and never got airborne to meet its attackers.

The Chaika first saw combat against the Japanese over Mongolia during the Battle of Khalkhin Gol in 1939. This aircraft came off worse against the Japanese Air Force.

Rows of captured I-153 in various states of repair. The Germans made no effort to reuse captured Soviet aircraft after they had overrun the Red Air Force’s air bases.

The Yakolev Yak-1 Krasavyets (beauty) was an attempt to produce a fighter on par with the British Hurricane and the German Bf109. However, the four-piece cockpit canopy resulted in poor visibility, and the instrumentation and gunsight were primitive. It appeared in 1940 and led to the more successful Yak-1M and Yak-7A.

A German cyclist stops to watch a souvenir hunter searching a Yak-1 fighter, which seems to have made a remarkable crash-landing in a dry riverbed and survived the impact.

A Soviet wartime expedient was the Yak-7A fighter, which was a conversion of the Yak-7V trainer.

The remains of a wheels-up crash-landed Yak-1. This aircraft was of mixed construction; fabric and plywood covered the aluminium airframe. In total, 8,721 of these aircraft were produced.

[Top, Above] The smashed remains of MiG-3 fighters that had only just come into service in 1941. At low to medium altitude it proved no match for the Luftwaffe’s Bf 109. As both aircraft are resting on their undercarriage it is likely that they were amongst the thousands of Red Air Force fighters destroyed on the ground by the Luftwaffe in the first few hours of Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa.