Circle of Death

Following the disastrous summer of 1941, General Aleksandr Novikov instigated a reorganization of the Red Air Force that in May 1942 witnessed the creation of independent air armies to replace the corps. These bigger formations consisted of five or more fighter aviation divisions, which offered a far greater punch. By 1944 these air armies included more than 1,000 fighters, bombers, ground-attack and reconnaissance aircraft. Also in 1942, in light of the German threat some forty fighter regiments were assigned to air defence. Until November 1942 the Red Air Force focused on rebuilding its ground-attack force in order to help stem the Nazi tide.

By far the best ground-attack weapon in the Soviet armoury was the famous Ilyushin ‘Flying Tank’, or Il-2 Shturmovik, which first appeared in 1941. This was designed as a low-level close-support aircraft capable of defeating enemy armour and other ground targets. Following early teething problems it developed into one of the world’s most potent ground-attack aircraft, armed with 23mm or 37mm cannon, machine guns, rockets and bombs, including anti-tank bomblets. With good cause, the Germans dubbed it the Schlächter (slaughterer).

Il-2 pilots developed the ‘Circle of Death’ for attacking panzers. They would circle around the enemy armour and peel off to make individual attack runs. When the run ended, they would rejoin their formation to wait for another turn. This kept the Germans under constant fire for as long as the Il-2s had ammunition left. Notably, during the summer of 1943 and the Battle of Kursk the Shturmovik finally came into its own, severely mauling the 2nd and 3rd Panzer divisions.

To support Hitler’s plans to smash the Red Army at Kursk, in the summer of 1943 the Luftwaffe massed everything it could spare to support Operation Citadel. General Hans Seidemann mustered 1,000 bombers, fighters, ground-attack and antitank aircraft in support of 4th Panzer Army’s Southern Pincer. The Northern Pincer formed by 9th Army was allocated another 700 aircraft under Major General Paul Deichmann.

In the meantime, the Red Air Force, invigorated by its success at Stalingrad and growing proficiency, felt confident enough to try to pre-empt Hitler’s offensive. Just as the Luftwaffe was about to take off from its five airfields around Kharkov on 5 July 1943, it discovered hundreds of enemy bombers bearing down on it. At the very point that Hitler’s Operation Citadel was launched, the German Army almost lost its vital air support.

At the eleventh hour the Luftwaffe was warned by radio monitors who detected increased communication between the Soviet air regiments. Also, the radar stations at Kharkov reported large formations of enemy aircraft heading their way. These included 285 fighters and 132 Shturmoviks from the Soviet 2nd and 17th Air armies. Panic ensued on the crowded Kharkov airfields and the bombers’ departure was postponed. The plan had been that they would take off first and gather over their bases to await their fighter escort.

Instead, German fighters at Mikoyanovka and Kharkov were scrambled and there followed the largest air battle of the war as they intercepted up to 500 Soviet fighters, ground-attack aircraft and bombers. General Seidemann reported, ‘It was a rare spectacle; everywhere planes were burning and crashing. In no time at all some 120 Soviet aircraft were downed. Our own losses were so small as to represent total victory, for the consequence was complete German air control in the 8th Air Corps sector.’

This was a major setback, for the Red Air Force committing so many fighters to this abortive pre-emptive strike meant that it was unable to challenge Luftwaffe supremacy on the southern flank of the Kursk salient, and in the north its response to Luftwaffe attacks was often ineffectual. Certainly in the northern sector Soviet fighters only began to react to Citadel in the late afternoon and Fw 190s brought down 110 Soviet aircraft by nightfall. Thanks to the poor performance of the two fighter corps with responsibility for providing front-line cover, both had their commanders replaced immediately.

To make matters worse, initial Red Air Force tactics designed to stop Hitler’s panzers were flawed. The Shturmoviks, armed with an array of cannon, rockets and anti-tank bombs, failed to get through. The Il-2s and Pe-2s were despatched in small groups lacking fighter escort and were easily picked off. This was soon remedied using regimental-size formations that were easier to escort and they broke through thanks to weight of numbers. Low-level bombing passes were abandoned in favour of dive-bombing at 1,000 metres at 30 or 40 degree angles. By 8 July, the German Army’s advance at Kursk had slowed and the Luftwaffe’s control over the battlefield was declining.

Supported by Gromov’s 1st and Naumenko’s 15th Air armies, a week later Zhukov launched his counter-offensive with the Western and Bryansk fronts. These were joined by Rudenko’s 16th Air Army on 15 July, when the Central Front went over to the offensive. In just five days, the 15th Air Army flew some 4,800 sorties whilst the 16th managed over 5,000, more than half of which were conducted by Pe-2s and Shturmoviks against retreating German troops.

Fortunately for him the Luftwaffe ensured that Hitler’s defeat at Kursk was not an even greater disaster than it could have been. On 8 July, Hs 129B-2s based at Mikoyanovka and commanded by Captain Bruno Meyer destroyed a Soviet armoured threat to 4th Panzer Army’s exposed left flank. To the north of Kursk, as the German offensive ground to a halt the German Orel salient came under threat as the Red Army sought to surround 2nd Panzer Army. Thanks to the Luftwaffe they narrowly avoided a repeat of Kalach, when the German Army had been cut off at Stalingrad.

Alarmingly, by 19 July 1943, Soviet tanks had reached Khotinez, cutting the vital Bryansk–Orel railway. Stukas operating from Karachev, supported by other anti-tank planes, bombers and fighters, flew to the rescue. For the first time a Soviet armoured breakthrough imperilling the rear of two whole armies was driven back from the air. Although during 19–20 July the Luftwaffe’s pilots prevented an even larger Stalingrad, this was to be its last major operation on the Eastern Front.

To the south the Red Army then sought to liberate Kharkov and the Red Air Force set about German armour, moving up to reinforce their defences. Kharkov was taken on 23 August and once the Kharkov airfields were lost the Luftwaffe withdrew to its bases at Dnepropetrovsk, Kremenchug and Mirgorod to help hold the Dnieper Line. It was once again spread over the whole front, providing direct support to the army. For the bombers, this was a death sentence.

During the last half of 1943, with about 8,500 aircraft Red Air Force numbers remained static, but over the first six months of 1944, it rapidly expanded to 13,500 planes. That year it introduced a new tactical bomber into service, the Tu-2, which was to play a key role in the Red Army’s final offensives. In addition, by 1943–44 some 12,000 Il-2s were in service and the Soviets were flying the IL-2m3 variant, which included a rear gunner. Similarly, the improved La-5FN and Yak-3 fighters appeared in 1943, which helped the Red Air Force wrestle air superiority from the Luftwaffe. By May 1944, the Soviet fighter squadrons were being equipped with an improved version of the La-5, known as the La-7. The Soviets’ dabbling with strategic bombers was half-hearted at best and dogged by engine problems. Production of the Pe-8 strategic bombers, which played a limited role at Kursk, was ended in 1944 after just seventy-nine had been built.

Britain and the Commonwealth supplied a total of 4,770 aircraft, whilst from 1942 until the end of the war America provided another 14,800, of which 9,438 were fighters. Stalin received new ground-attack aircraft in 1944 courtesy of the Americans, principally the Bell P-63 Kingcobra, an upgrade of the earlier P-39 Aircobra, the P-40 and the P-47. The Soviets received about 2,000 P-40s by March 1944, but they did not like them, considering them cast-offs, and the aircraft were largely relegated to training. Only 200 P-47s were sent during 1944–45; in contrast they received 2,421 P-63s, which were based on a proven and well liked design. The Soviets found the Aircobra, armed with a 37mm cannon, to be an excellent ground-attack aircraft. They nicknamed it Britchik (little shaver) and received 4,750 of these.

However, by this stage in the war the Soviets were keener on bombers and transports, as their factories were producing fighters equal or superior in quality and in plentiful numbers. During 1944 aircraft production reached 40,300 machines. To supplement the Soviet bomber force the Americans provided 2,908 A-20 Havoc light bombers and 862 B-25 Mitchell medium bombers.

By the time of Operation Bagration the Soviets had got the hang of their American-supplied fighters. Two years earlier, for fear of American spies or simply national pride, Stalin had refused offers of American pilots and mechanics. The results, as American journalist Walter Kerr recalled, were predictable:

One result was that in the early months when they used our Aircobras and B-25 medium bombers, many were damaged through inexperienced handling. Both planes have a nose wheel, which has led to their being called planes with a tricycle landing gear. In fact, they should be landed on two wheels, then nosed over on to the front wheel as the pilot taxis across the field. The Russians, however, tried to land them on three wheels, and the relatively weak forward wheel frequently broke.

The Americans secured agreement with Stalin for their air force to operate from the Soviet Union in 1944. Apart from the RAF fighter squadron based at Murmansk to help protect the Arctic convoys, this was Stalin’s only concession to the Western Allies’ desire to operate from his territory.

Nikita Khrushchev recalled:

I got my first glimpse of Americans in the late spring or early summer of 1944 near Kiev. It was a bright, warm day. Suddenly we heard a rumbling noise in the distance. We scanned the sky and saw a large formation of airplanes flying toward us. I’d never seen this type of plane before. I realized they must be Americans because we didn’t have anything like them in our own air force. I certainly hoped they were American; the only other thing they could have been was German. I later found out that these planes were B-17 ‘flying fortresses’ and were based outside Poltava as part of our agreement with [President] Roosevelt.

Dubbed Operation Frantic, the Americans had considerable expectations of this shuttle bombing of Germany. However, the success was short-lived thanks to the Luftwaffe. Khrushchev noted: ‘Somehow the Germans were able to track the American bombers back to Poltava and bomb their base. I received a report that many planes had been destroyed and many lives had been lost. Most of the casualties were our own men whom we had provided as maintenance personnel at the base.’

This retaliatory raid took place on 21–22 June 1944. Only eighteen American missions were flown, the whole operation largely being stymied by Stalin, who suspected American motives.

Despite its shortcomings the I-16 was flown by a number of Soviet aces, including Senior Lieutenant A.G. Lomokin, Captain B.F. Safonov and Senior Lieutenant M. Vasiliev. In 1943 it was still in service as a fighter-bomber, but its speed put it at a disadvantage when faced with faster and more manoeuvrable enemy fighters. Losses of I-16 at Kursk ensured it was subsequently withdrawn from operational service.

The Lavochkin La-5 fighter was first tested operationally over Stalingrad by a specially formed trials regiment in September 1942. They found it a vast improvement over the much maligned LaGG-3; early combats showed it to have a better all-round performance than the Bf 109G, except its climb rate was not as good. To remedy this shortcoming the modified La-5FN appeared in March 1943 and helped the Red Air Force establish air superiority for the first time.

The Junkers Ju 87 G-2 was nicknamed the Panzerknacker (tank cracker) or Kanaonenvogel (cannon bird) and was armed with a pair of under-wing Flak 18 37mm cannon with twelve rounds per gun. This proved capable of destroying all but the heaviest Soviet tanks with its tungsten-cored rounds. Even the Soviet T-34 medium tank was not immune to the G-2.

A German bomber pilot scans the skies; a sudden speck on the horizon would lead to chatter on the radio, warning the gunners they were under attack. By 1943, the Luftwaffe’s twin-engine bombers were very vulnerable to enemy fighters when flying without escort.

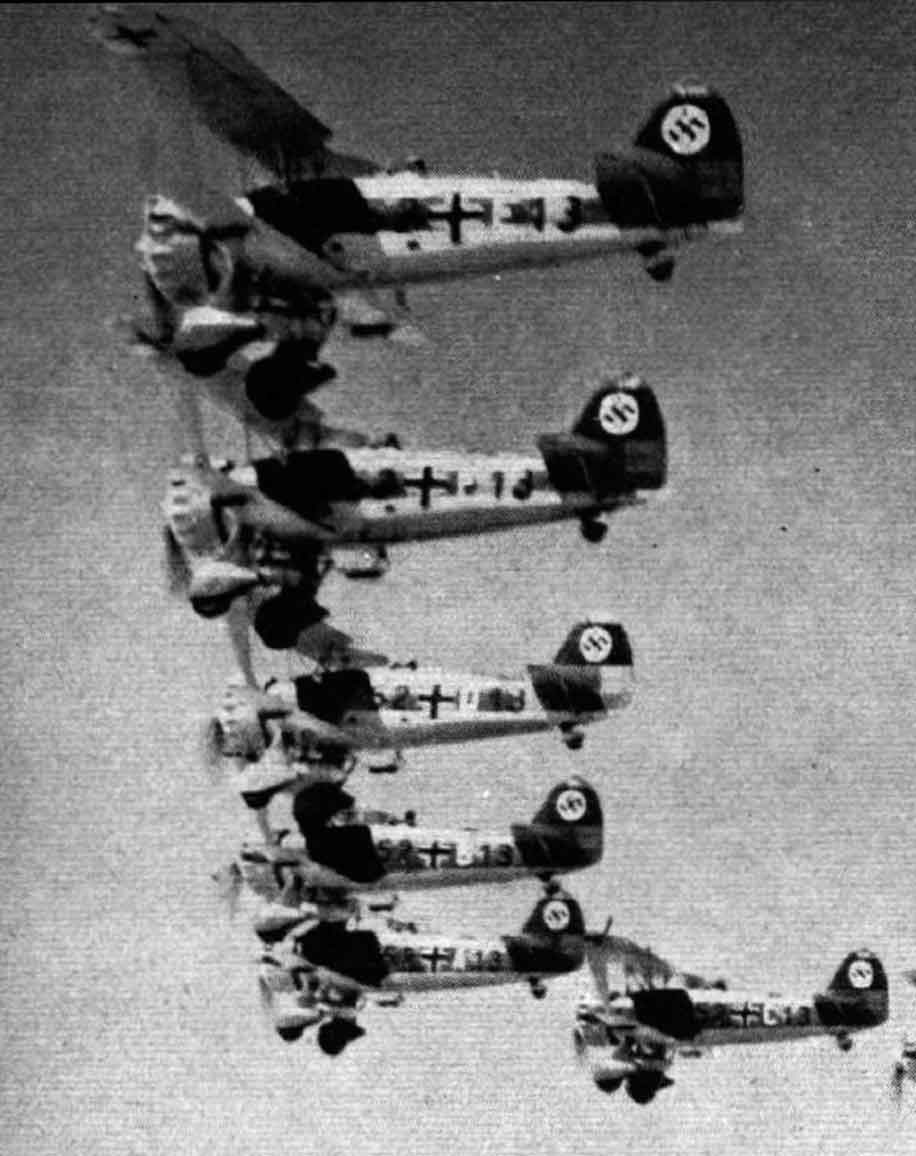

A flight of Il-2 Shturmoviks. The two-seat variant first appeared over Stalingrad at the end of October 1942. The following year, the Il-2M was produced armed with 23mm cannon and the Il-2m3 with 37mm cannon. On 5 July 1943, a force of 132 Shturmoviks – part of a fleet of 500 aircraft – launched a surprise attack on the Luftwaffe’s airfields around Kharkov.

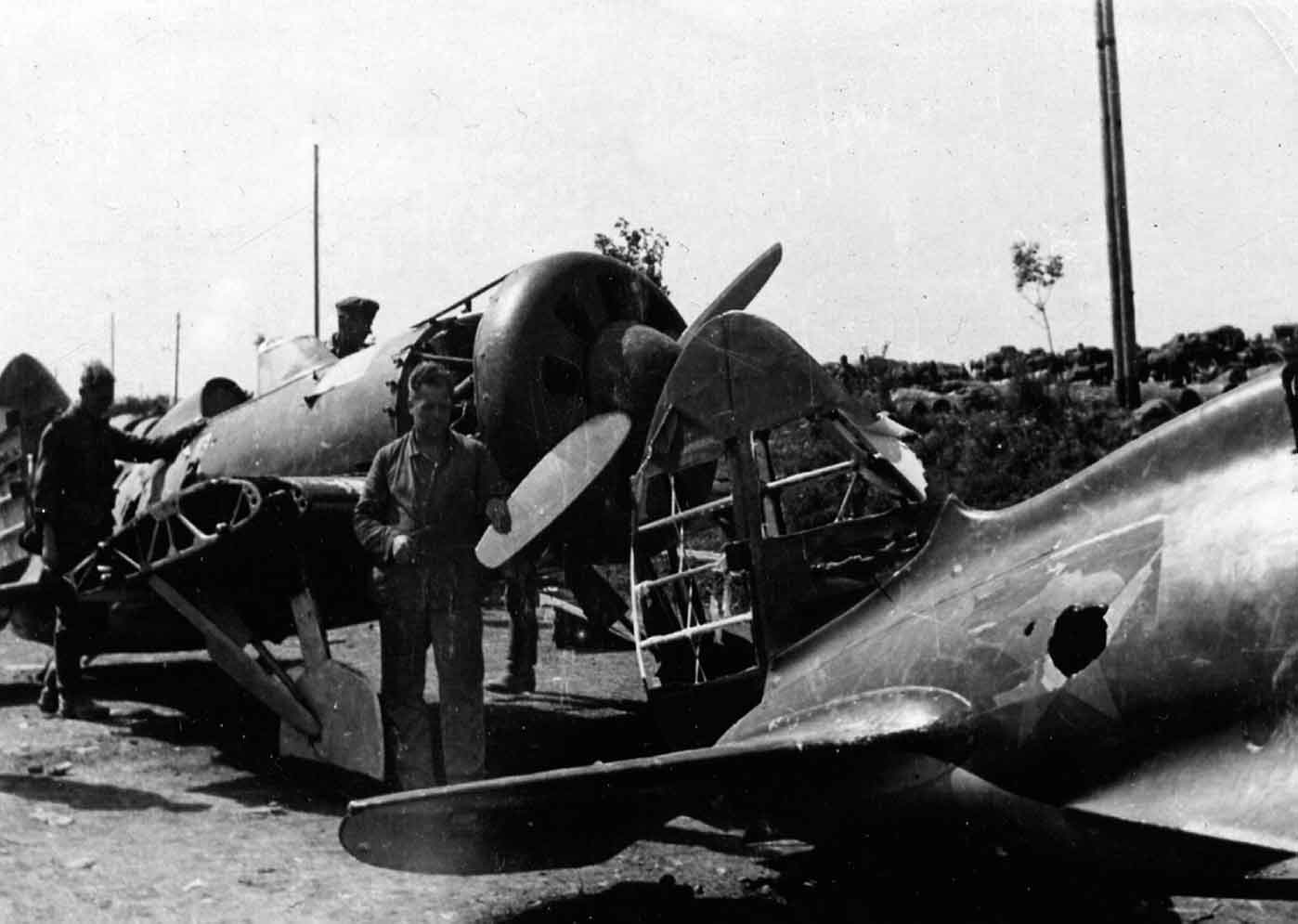

What appears to be the remains of a Soviet SB-2 bomber. An upgraded variant was the SB-2bis, which had up-rated engines and greater fuel capacity. The Luftwaffe was forewarned of the Red Air Force’s attack at Kharkov and managed to shoot down 120 aircraft.

German troops pose on a crashed single-seat Il-2. The large undercarriage fairings on the wings left the retracted undercarriage partially exposed, but meant the pilot could make a belly-up landing without too much harm to the aircraft. In this instance the propeller and the wing have been damaged; the bent propeller props indicate the engine was still running when it hit the ground.

A tail section is all that remains of this obliterated bomber. The loss of so many aircraft from the Soviet 2nd and 17th Air armies on 5 July 1943 in the pre-emptive strike on the Luftwaffe at Kharkov meant the Red Air Force was unable to challenge Luftwaffe superiority over the Kursk salient during the opening stages of Hitler’s Operation Citadel.

Little remains of this Il-2 – the circular metal tube projecting from the propeller spinner is not a weapon, rather a starter dog used for turning and firing the engine in the same way as a vehicle starting handle.

A German souvenir hunter collects the remains of a Soviet aircraft that came down in some woods. The splintered trees were probably a result of the crash.

Heinkel He III bombers were deployed to support Hitler’s Operation Citadel but they proved vulnerable to Soviet Yaks and MiGs.

Introduced in 1942, the German Henschel Hs 129, armed with a 30mm cannon, like the Ju 87G-2 was nicknamed the Panzerknacker (tank cracker) but was never available in sufficient numbers as only 865 were ever built. Nonetheless, on 8 July 1943, HS 129s played a key role in defending the 4th Panzer Army’s exposed flank.

Likewise, on 19 July 1943, Stukas helped prevent the German 2nd Panzer Army from being surrounded in the Orel salient.

Although the Henschel Hs 123A biplane was obsolescent it remained in service on the Eastern Front until 1944. The Hs 123C variant was armed with a 20mm cannon.

A Russian cornfield became the last resting place for this Il-2. In the opening stages of Citadel Shturmovik tactics proved flawed. Initially, the Il-2s and Pe-2s flew in small groups without fighter cover and proved easy pickings for enemy fighters. Once the formations were beefed up they were able to fight their way through and dive-bomb the panzers.

Another Shturmovik that came down on the Russian Steppe.

The Red Air Force received both British and American aircraft, including this Hurricane. The Soviet officer on the left is watching the RAF pilot getting into his parachute.

This Russian house had a near miss judging by the wreckage of this Soviet aircraft.

The Ju 87 was also operated by the other Axis allies, including the Bulgarian, Hungarian and Romania air forces.

A heavily touched up Soviet propaganda shot showing Shturmoviks attacking a column of panzers. The wartime caption reads, ‘Soviet attack planes annihilating a German tank column’.