Heroes of the Soviet Union

The term ‘ace’ was first officially used by the Soviets in December 1941 to describe a pilot with three or more confirmed kills. This was revised by the end of the following year to at least ten, which earned the pilot the Gold Star of the Hero of the Soviet Union. They were used as morale boosters and their names and exploits were made public by Stalin’s propaganda machine.

Ivan Kozhedub, with sixty-two enemy aircraft downed, became the highest scoring Allied pilot of the Second World War. At least six other pilots – Grigori Rechkalov, Aleksandr Pokryshkin, Nikolai Gulayev, Kirill Yevstigneyev, Nikolai Skomorokhov and possibly Nikolai Shutt – are believed to have scored fifty or more. Vladimir Lavrinenkov claimed some twenty-three and Vladimir Orekhov nineteen personal and three group kills. The confirmation process was quite stringent, requiring proof from two other pilots involved, from ground troops, partisans or verification on recaptured territory. The decision to confirm personal or group kills varied from unit to unit, and some group kills were deemed personal, with the lead attacker getting the credit.

Flying the La-5FN and the La-7, Kozhedub clocked up his impressive total after flying 326 operational sorties and engaging in 126 combats. All of his victories were against conventional piston-engined aircraft, with the exception of one Me 262 jet fighter. His exploits were widely reported and he was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union three times. He survived the war and went on to fly over Korea in the early 1950s.

Rechkalov, although accused of being a dangerous glory hunter by fellow ace and superior officer Pokryshkin, was involved in 122 air battles, during which his total reached fifty-six personal and five group victories. Despite being relieved of his command for failing to support his comrades in air-to-air combat he was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union twice and survived the war.

Pokryshkin graduated from the Kacha Air Force Pilots’ School in 1939 and went on to fly more than 600 sorties. He fought in 156 air engagements, achieving fifty-nine kills, including up to six group kills. He initially flew the troublesome MiG-3, followed by the Yak-1 and then the lend-lease P-39 and P-63. He saw action on the opening day of the war and in May 1944 was appointed commander of the 9th Guards Fighter Aviation Division, seeing combat on the Caucasus and Ukrainian fronts. He survived the war and was awarded Hero of the Soviet Union on three occasions.

In June 1941 Boris Safonov was commanding a squadron of I-16s. He then became one of four Northern Fleet pilots to convert to the British Hurricane and served as an instructor for Soviet pilots assigned to the aircraft. The first double Hero of the Soviet Union winner, Safonov was the first Soviet fighter ace to achieve twenty-four personal kills and fourteen group kills, before being killed in his P-40 on 30 May 1942. On his last mission he destroyed three Ju 88s before being hit and ditching in the sea.

Nelson Gevorgovich Stepanyan was a Soviet Shturmovik fighter ace who was dubbed the ‘Storm Petrel of the Baltic Sea’. Before his death in 1944 he conducted 239 combat missions and in that time destroyed 600 armoured vehicles, eighty tanks, fifty-three ships and twenty-seven aircraft, which was quite a tally by anyone’s reckoning.

Stepanyan was in fact not Russian or Ukrainian, but an Armenian, having been born in Shusha, Elisabethpol Governorate in 1913, although his family moved to Yerevan, the Armenian capital, when he was young. He studied at military school and went on to become a flight instructor at the Bataisk Naval Aviation School in the mid-1930s. When Hitler attacked the Soviet Union Stepanyan was instructing at another flight academy.

In response to this assault on his motherland Stepanyan volunteered for active duty. He was assigned as a pilot to a Ilyushin Il-2 fighter-bomber squadron deployed in the Baltic region. Serving with the 2nd Air Squadron, 8th Air Brigade, 57th Division he was involved in the battles to defend Leningrad, which was soon besieged by the Germans and Finns. By November 1942, Stepanyan was reported to have single-handedly knocked out seventy-eight enemy trucks, sixty-seven tanks, sixty-three anti-aircraft guns, thirty-six railroad cars, twenty merchantmen and warships (including a destroyer), nineteen mortars, thirteen fuel tankers, twelve armoured cars, seven long-range guns, five ammunition dumps and five bridges.

The following year he was promoted to the rank of major and took command of the 47th Fighter Division. They supported the Soviet offensives in the Crimea around Sevastopol, Sudak and Theodosia. For their heroic exploits against the German and Romanian forces in the Crimea Stepanyan’s formation was redesigned the Guards 47th Theodosia Fighter Division.

In May, Stepanyan and his triumphant division returned to the Baltic Front to fight against the Germans and their Finnish allies. He had on one occasion been shot down behind enemy lines, but by good fortune fell in with Soviet partisans who escorted him back to Soviet lines so that he could resume his part in the air war. His luck ran out on 14 December 1944, when he was on patrol over Liepāja, Latvia. His aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire and he died crashing his plane into a German warship.

His pilots were so devastated by his loss that they wrote to his parents saying, ‘We all wept when Nelson Gevorgovich failed to return on that fateful day. They say that tears bring comfort. But the few tears of a soldier, like the red-hot drops of metal, burn the heart and call for vengeance.’ Stepanyan was awarded the highest honour with the title of Hero of the Soviet twice, the second time posthumously. He also gained the Order of Lenin twice and the Order of the Red Banner three times.

At the onset of the Second World War, whilst there were no formal restrictions on women serving in combat roles with the Soviet armed forces, initially the Soviet authorities did all they could to discourage them. Despite this, women did become fighter and bomber pilots flying with the Red Air Force. Marina Mikhailovna Raskova is known as the Russian Amelia Earhart because of her civilian flying exploits. In 1933 she was the first woman to become a navigator in the Red Air Force and during the war she formed three all-female aviation regiments (the 586th, 587th and 588th).

It is said that Raskova used her connections with Stalin to get women accepted as combat pilots. She commanded the 587th Bomber Aviation Regiment (also known as the 125th Guards Bomber Aviation Regiment), which flew the Petlyakov Pe-2 twin-engine dive-bomber. This caused resentment amongst many male pilots operating obsolete aircraft. Tragically, Raskova was killed making a forced landing on 4 January 1943.

The first all-female unit to take part in combat was the 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment, which went into battle on 16 April 1942. It was involved in 125 air battles and shot down thirty-eight enemy aircraft. They operated the Yak-1, which appeared in 1940 and led to the more successful Yak-1M and Yak-7A. Yekaterina Vasylievna Budanova, who was credited with eleven victories, along with Lydia Litvyak became one of the world’s first female fighter aces.

After working in an aircraft factory in Moscow, Budanova became a flight instructor in the late 1930s and took part in several air parades flying the single-seat Yakolev UT-1. After the German attack she joined the air force and was assigned to the 586th Fighter Regiment.

Piloting the Yak-1, Budanova flew her first combat missions over Saratov in April 1942. That September, along with Lydia Litvyak, Maria M. Kuznetsova and Raisa Beliaeva, she was sent to join the 437th Fighter Regiment based on the east bank of the Volga. There they were involved in the Battle of Stalingrad.

Because the 437th was operating the LaGG-3 fighter, its commander, Major Khvostikov, was sceptical about the women’s capabilities. He was soon proved wrong and on 14 September 1942, Budanova and Litvyak shot down a Bf 109. Budanova then achieved her first solo kill on 6 October, when she claimed a Junkers Ju 88 bomber. Then, from October until January 1943, she and Litvyak fought with the 9th Guards Fighter Regiment in the Stalingrad area. This unit was made up of aces or potential aces. Initially the two women flew together but then operated separately as wingmen to male pilots.

In January 1943, the 9th Guards Fighter Regiment was re-equipped with American-supplied Bell P-39 Cobra, and Budanova and Litvyak were sent to the 296th Fighter Aviation Regiment so they could continue to fly Yaks. Budanova was awarded the Order of the Red Star on 23 February 1943. On the morning of 19 July 1943, she took off for an escort mission and near the city of Antracit in Luhansk Oblast became involved in a dogfight. Seeing three Messerschmitts going for the bombers she was escorting, Budanova attacked them, shooting down two. Wounded, and with her own plane on fire, she managed to land, but when some local farmers pulled her clear they found she had died of her injuries.

Budanova was twice awarded the Order of the Patriotic War, but it was not until 1993 that she was posthumously awarded the title Hero of the Russian Federation in lieu of the Hero of the Soviet Union. Lydia Litvyak also achieved about a dozen victories, but was killed shortly after her friend, on 1 August 1943. President Gorbachev posthumously awarded her the Hero of the Soviet Union on 6 May 1990.

The third all-female unit, the 46th Taman Guards Night Bomber Aviation Regiment, started life as the 588th Night Bomber Regiment. The practicalities of war meant that only the 588th remained all-female. Major Tamara Aleksandrovna Kazarinova, commanding the 586th, was replaced by a man in October 1942; likewise, after Raskova’s, death a man took charge of the 587th. In addition, the top rear machine-gun position on the regiment’s Pe-2 dive-bombers required someone tall; as not all the women met this criterion, men joined the crews as radio operators/tail gunners and flew with them.

The 588th Night Bomber Regiment flew with the 4th Air Army from June 1942. It was reorganized as the 46th Guards Night Bomber Aviation Regiment the following year and was then honoured with the title ‘Taman’ after taking part in the battle for the Taman Peninsula. In light of the regiment’s U-2/Po-2 being a wood and canvas-built biplane, it did not seem best suited for modern aerial warfare or even being relegated to night raids. However, its maximum speed was slower than the stall speed of both the Bf 109 and the Fw 190, which made it difficult to shoot down. Also, to avoid flak and alerting the enemy on approach to target, they developed the tactic of idling the engine and gliding to bomb release point. This was particularly unnerving for those being bombed and led to the German nickname of Night Witches.

The Night Witches became the most highly decorated female unit, with twenty-three of its members being awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union. The regiment flew more than 23,000 sorties, dropping 3,000 tons of bombs for the loss of thirty crew. Each pilot flew more than 800 missions and often multiple ones; for example, Nadezhda Popova flew eighteen sorties in a single night.

This was how Soviet pilots liked to see themselves – cast in a heroic and dashing mould. This Yak pilot is L. Tomalchen, who was photographed in the Stalingrad Front in early 1943. He had just returned from combat involving seven enemy planes, during which he shot down a Heinkel and damaged a Ju 87.

Another pilot posing for the camera, this time with his Il-2. Ground-attack pilots produced aces as well as the fighter pilots; most notable was Nelson Stepanyan, who was credited with destroying an incredible 600 armoured vehicles, eighty tanks, fifty-three ships and twenty-seven aircraft. Not surprisingly, in light of his naval victories he was dubbed the ‘Storm petrel of the Baltic Sea’.

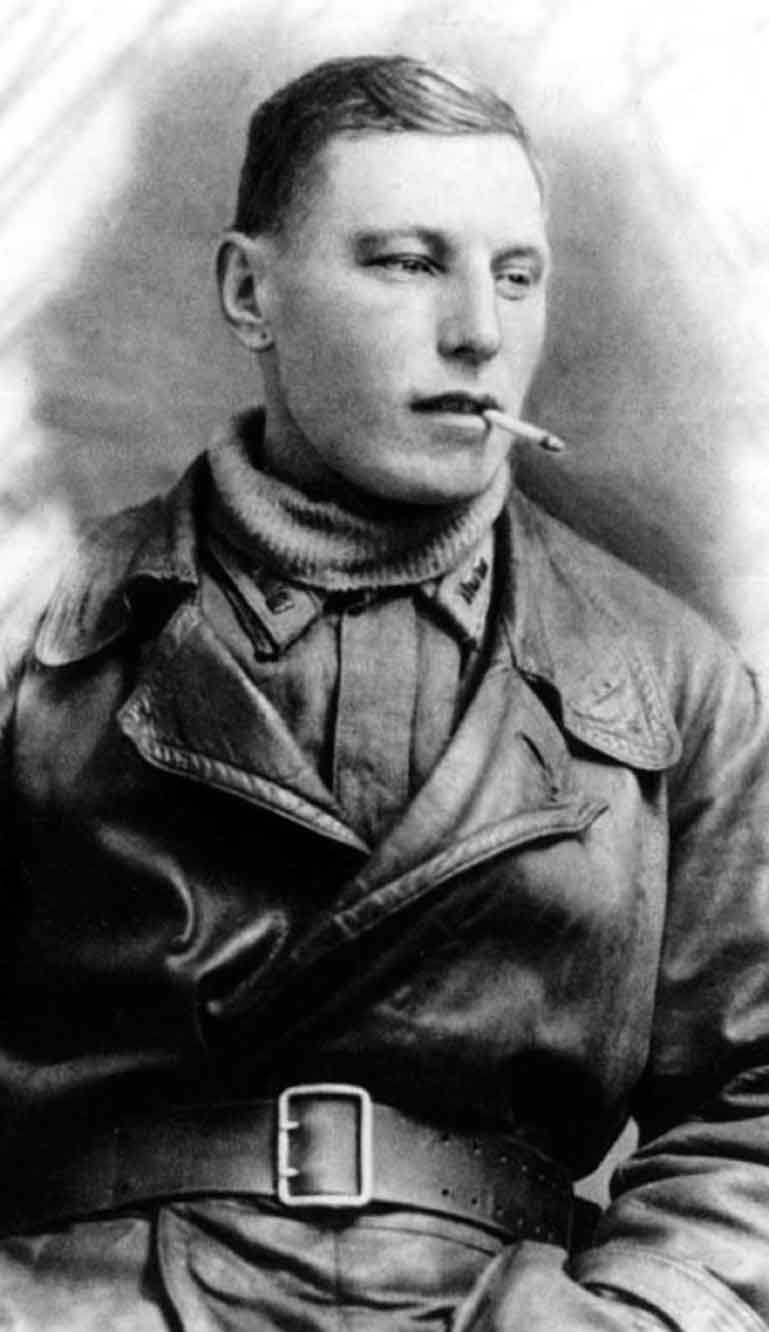

Looking tough, cigarette between his lips, Aleksandr Pokryshkin was made a Hero of the Soviet Union on three separate occasions. He started the war flying the MiG-3, scoring almost twenty victories in this aircraft. Pokryshkin then converted to the Yak-1 and the Bell P-39 Aircobra. He refused to convert to the La-5 on grounds its firepower was insufficient. He also cancelled a conversion to the La-7, opting for the Bell P-63 Kingcobra. During his career he brought down fifty-nine enemy aircraft, although Pokryshkin himself put the figure at nearer 100.

Young Lydia Litvyak was the top female Soviet fighter pilot; she clocked up twelve solo victories and at least four shared kills during sixty-six combat missions. She was the first female fighter pilot to shoot down an enemy plane and the first female pilot to gain the title fighter ace. She was killed at the age of just twenty-one on 1 August 1943, during the Battle of Kursk. Her friend Yekaterina Budanova, credited with eleven victories, was killed on 19 July 1943.

Soviet ground crew preparing a Shturmovik for take-off. The two-seat Il-2M featured a rear-facing 12.7mm machine gun in a heavily armoured cockpit area in addition to the 23mm forward-firing cannon in the leading edges of the wings. Note the Polikarpov U-2/Po-2 biplane just visible in the background.

[Top, Above] German troops examine early model single-seat Il-2s. The first aircraft appears to have crash-landed while the second one was abandoned after being damaged.

The Polikarpov U-2 (supplemented by the R-5 and R-Z) was widely used on the Eastern Front in a variety of roles. As a light bomber it proved vulnerable to enemy flak so in 1942 was deployed in a night bomber role. Its main claim to fame was with the all-female 588th Night Bomber Regiment nicknamed the Night Witches.

This Soviet armourer is arming the bomb load on a U-2. This aircraft could take six 50kg (110lb) bombs, which, delivered at night from low level, had a devastating effect on German morale.

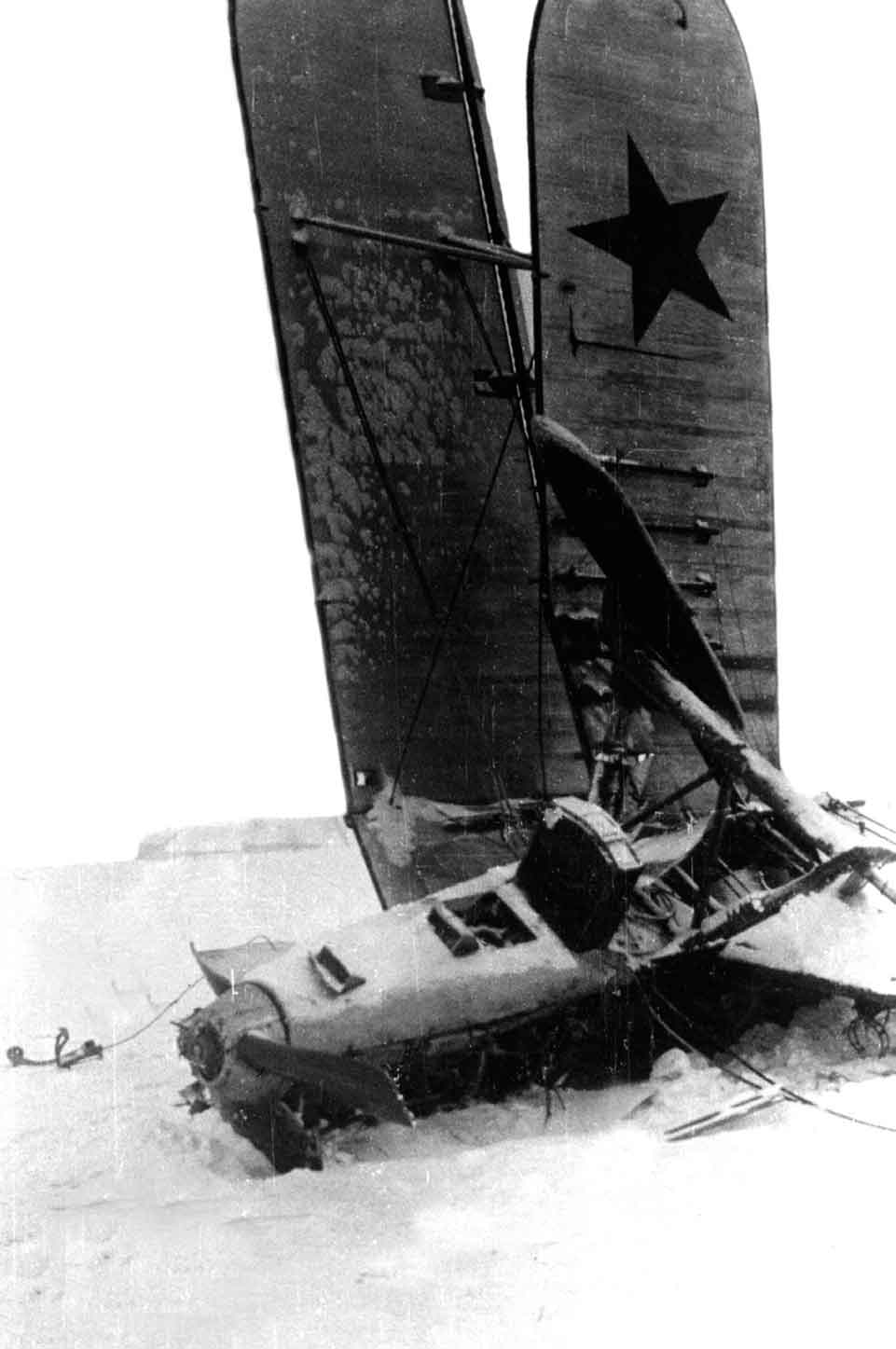

This R-5 or R-Z fitted with skis for winter operations ended up upside down and was either shot down or suffered a take-off accident. The Red Air Force was equipped with some 5,000 R-5 and 1,000 R-Z. They could carry 250kg (550lb) and 400kg (882lb) of bombs respectively.

A portrait for the family extolling the virtues of the Il-2m3 and the U-2. The Soviets were quick to appreciate ground-attack aircraft.

Focke-Wulf Fw 190s on a very wet and muddy airstrip. Luckily for the Luftwaffe it could cope with such rough and semiprepared airstrips. The A-5, introduced in early 1943, was an excellent fighter. Its range, speed and manoeuvrability were notably superior to the Bf 109. However, the Lavochkin La-5, favoured by Soviet fighter ace Ivan Kozhedib, was faster than both.