“Super heroes have a way of arriving just when they’re needed and so did Kirby. Every time the comic book industry needed someone to kick it in the butt or in a new direction, along came Jack. He was like the cavalry with a pencil.”

— WILL EISNER, COMICS CREATOR

THE FUTURE JACK KIRBY was born Jacob Kurtzberg on August 28, 1917, the son of Benjamin and Rosemary Kurtzberg, who resided on Essex Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Another brother, David, followed two years later, by which time the Kurtzbergs had moved to a slightly larger (but still cramped) Suffolk Street tenement house.

Their parents had migrated from Austria some time around the turn of the century. “My father had insulted a member of German aristocracy,” Jack recalled. “The German, who was an expert marksman, challenged him to a duel. My father knew he’d be killed, so he decided to emigrate. All the relatives chipped in for the tickets.” Benjamin, a tailor by trade, obtained intermittent employment in New York garment factories, often getting up before dawn to walk to work.

Even putting in relentless hours, Ben Kurtzberg had trouble making ends meet. “From the time I was old enough to deliver papers,” Jack recalled, “I was aware that the income was necessary. It was that way in all the families in our neighborhood. Whatever you could bring home counted.

“But I was terrible at selling papers,” he continued. “You’d have to go to this building and pick up your papers from the back of a truck. I was the shortest guy and the other boys used to run right over me.” He fared slightly better with an array of messenger jobs and sign-painting chores, but as each ended, he was back with the newsboys, jostling to claim his bundle. It was a metaphor for his life ahead.

The money helped the Kurtzbergs buy groceries, and his parents would allow him a few nickels for his own entertainment and enlightenment. Enlightenment, mostly. Young Jakie, as most called him, avidly read pulps, eagerly followed (and copied) newspaper comics, and frequently spent all afternoon at the local cinema. As he later explained, “The pulps were my writing school. Movies and newspaper strips were my drawing school. I learned from everything. My heroes were the men who wrote the pulps and the men who made the movies. Every hero I’ve written or drawn since then has been an amalgam of what I believed them to be.

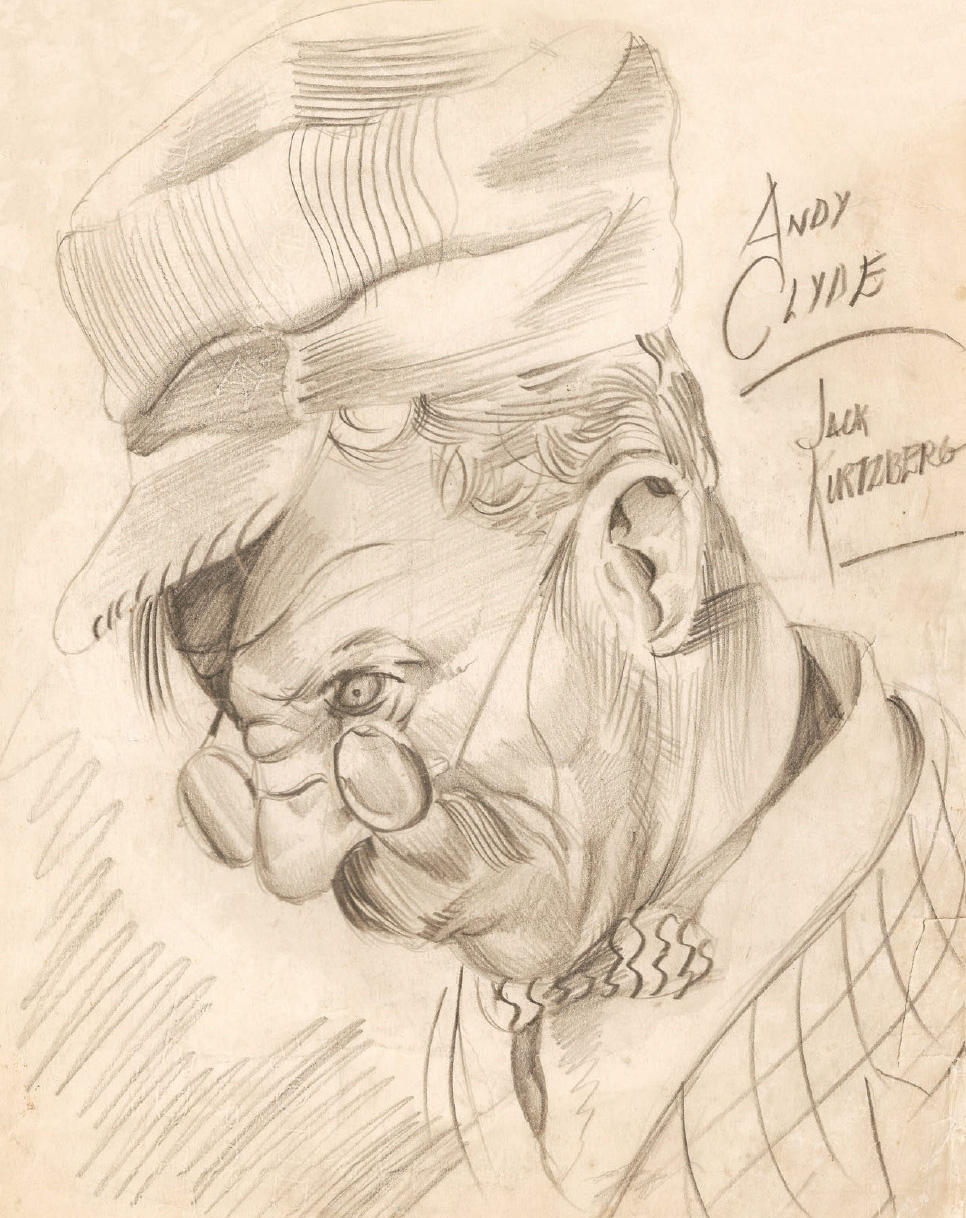

Above and following page

Childhood sketches

Art: Jack Kurtzberg (age 17)

1934

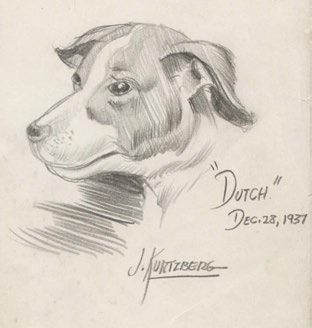

Childhood sketch

Art: Jack Kurtzberg (age 18)

December 28, 1937

“At times, I felt like I was being raised by Jack Warner. My mother would come and get me. She’d go to the doorman, and he knew which kid to drag out of the balcony. Even then, I’d plead with him, ‘Just let me see this next scene again.’ Those scenes still appear in my work.”

Jakie soon became a member of the Suffolk Street Gang. “Each street had its own gang of kids, and we’d fight all the time. We’d cross over the roofs and bombard the Norfolk Street Gang with bottles and rocks and mix it up with them.” Years later, in the Fantastic Four comic books, Ben “The Thing” Grimm—an obvious Kirby self-caricature—would fight a running battle with a mob called the Yancy Street Gang. The references to Jack’s childhood—and skirmishes with the gangs of his childhood—would be unmistakable.

Then there was the Boys Brotherhood Republic, one of many organizations of that era founded to put restless youths on the road to solid citizenry. Young Kurtzberg was already well onto that path but he signed up because, as he later put it, “It was a good place to make friends. In my neighborhood and with my height, I needed all the friends I could get.” Jakie and his new acquaintances launched the club’s mimeographed newsletter, The B.B.R. Reporter. It wasn’t much of a publication—the members had to practically beg family and neighbors to buy it—but it did feature the earliest published cartooning by the future Jack Kirby. (The staff photographer, Leon “Albie” Klinghoffer, became a lifelong Kirby friend . . . right up until 1985 when Palestinian terrorists hijacked the cruise ship Achille Lauro and executed a wheelchair-bound American tourist. The world was outraged at the murder of Leon Klinghoffer, and Jack was more outraged than anyone over the loss of his friend.)

A meeting of the Boys Brotherhood

Republic. Jack Kurtzberg is at top right.

1935

When he wasn’t reading or fighting, Jakie was drawing the visions he saw in his head. Many came from the newspaper strips he came to love and follow. And when he didn’t have paper, he’d draw on whatever was around: “I’d get the Daily News and the Journal,” he recalled. “Sometimes, we’d get them out of the neighbors’ trashcans, if they hadn’t been used to wrap fish. I’d read Barney Google and Jiggs and Maggie, and then I’d sit down and draw Barney Google and Jiggs and Maggie.” As major influences, he would later cite Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond, and Hal Foster, along with editorial cartoonists like C. H. Sykes, “Ding” Darling, and Rollin Kirby. For a time, he really wanted to be Rollin Kirby but would ultimately settle for the surname.

“I’d doodle on the floor of the tenement. I’d stay there all day until the janitor came in and found me and beat the hell out of me.” His parents finally realized that the lad was not about to stop drawing and, though strapped for cash, they began buying him large pads of onionskin drawing paper. Jakie filled each tablet so rapidly that they began to ration them.

With parental approval, he dropped out of school, just shy of the twelfth grade. That was how critical it was to the family to have that weekly paycheck coming in. He would traipse around Manhattan with art samples, praying to land something that paid before his father ordered him to forget about drawing and apply at some factory.

By now, Jacob had become Jack. At least, everyone outside his immediate family was calling him that. He could feel himself changing in other, more meaningful ways. “I wanted to break out of the ghetto,” he recalled years later. “It gave me a fierce drive to get out of it. It made me so fearful that in an immature way, I fantasized a dream world more realistic than the reality around me.”

He may also have fantasized the tale of his one day at Pratt Institute, a story he told often in later years. Details changed with each telling, but essentially involved him landing a few minor illustration jobs—minor in both importance and salary. These jobs, he said, turned around his father’s attitude about there being money in drawing. It was arranged for Jack to enroll in the famed art school, but the very next day Ben Kurtzberg lost his latest tailoring job, and his son had to quit art school.

With or without a day of Pratt on his résumé, Jack continued searching for work. For a time, he and his father took on a pushcart concession, dragging a wobbly wagon to outlying areas of Manhattan to sell day-old baked goods. Jack decorated their “storefront” with hand-painted cartoons and, as he later explained, that paid off: “The other vendors saw them and asked if I’d paint signs for them, which I did. I made more money painting signs than hauling the pushcart around, but either way it wasn’t much.”

Finally, he found work drawing. Well, not exactly drawing, but it was near people who did.

In the spring of 1935, Jack answered a newspaper ad for artists. It led him to the heart of New York’s Times Square and the Max Fleischer animation studio, producers of the Popeye and Betty Boop cartoons. There, Jack started at the bottom-feeding job in the house—opaquing cels. It paid poorly, the work was uncreative, and Jack didn’t get along with his bosses. “Too cocky, too eager to move up” was the rap on him. Cartoon studios expected you to starve for years while you learned your craft and advance to the good positions over time.

Young Kurtzberg couldn’t wait. He insisted on auditioning over and over, practically every week, for the next rung up . . . and in record time, he did advance to clean-up work. Then it was on to assistant animating, another position that didn’t pay well and involved little creativity. In animation, you drew what you were told, copying other artists’ drawings and working in other artists’ styles on stories and characters you didn’t create. The whole oppressive factory atmosphere further convinced him he might be fighting his way up the wrong ladder.

The Max Fleischer Studio, located at 1600 Broadway near Times Square in New York. Kirby later called it, “A great place to get out of.”

One of young Kurtzberg’s try-out drawings for an assistant animation job on Fleischer’s Popeye cartoons. The first cartoon he worked on in that capacity appears to have been “Clean Shaven Man,” which was released in February 1936.

The rumors solidified those feelings. Word was that the studio might go on strike . . . or to avoid a strike, the Fleischers might up and move the whole thing to Florida, a right-to-work state. The latter was what happened, but by that time Jack Kurtzberg had departed.

While making the rounds, he’d met a man named H. T. Elmo who operated the Lincoln Features Syndicate, an outfit that sounded more impressive than it was. Seeking escape from the Fleischers, Jack bombarded Elmo with samples and landed a position with a meager salary—less than what he’d made drawing Popeye—but with a scale of lucrative-sounding bonuses if his output boosted the syndicate’s receipts.

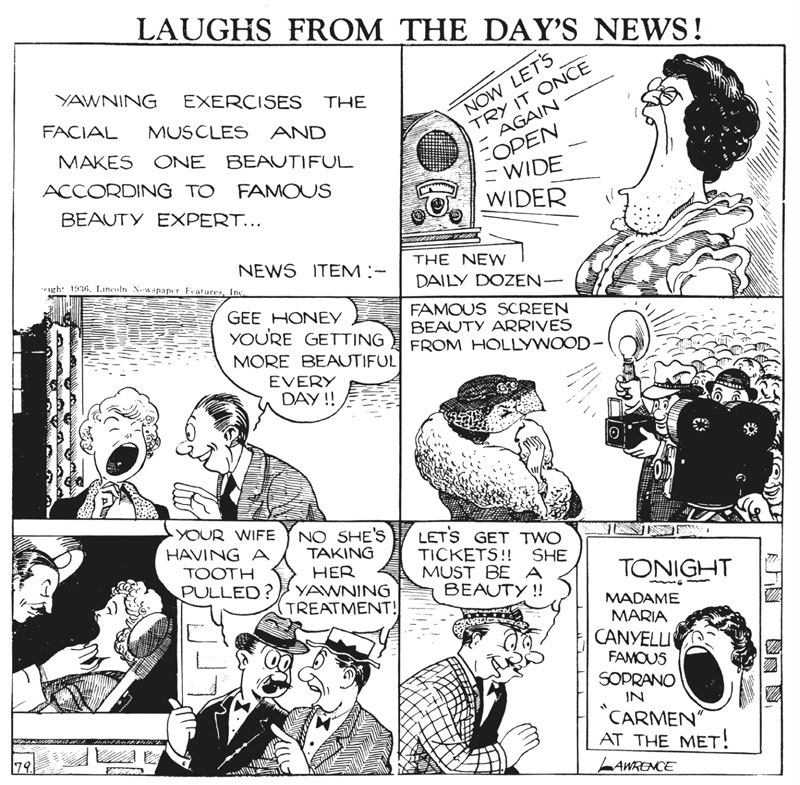

It was a job drawing comic panels for syndication, though just barely. Lincoln offered low-priced wares to papers that either could not afford the product of larger syndicates, or who operated in cities where larger papers had locked up all the popular strips. To this end, Elmo paid low fees and instructed his artists to replicate what the big boys were selling. Can’t get Ripley’s Believe It or Not! for your newspaper? Then why not try our Curious Customs and Oddities? Until Kurtzberg came along, what Elmo offered were pretty much the exact same features as the majors but without the quality.

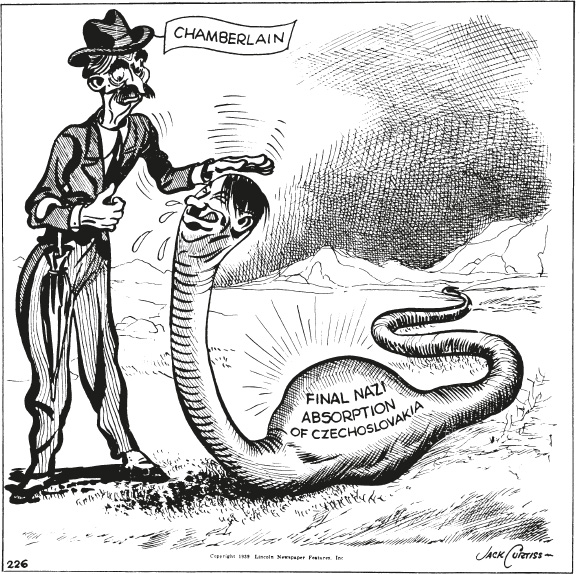

To maintain consistency as artists came and went, and to make Lincoln seem more professional, each feature carried a permanent, spurious byline. “Brady” illustrated Our Puzzle Corner and “Lawrence” was responsible for Laughs from the Day’s News!, but neither artist existed. One feature—a panel of medical facts called Your Health Comes First—was signed “Jack Curtiss,” a name Kirby would use on several early projects, including many of the political cartoons he drew for Lincoln.

For Jack, it was a period of many firsts, chief among them the first time he saw his comic art receive professional reproduction. It was also the first of many instances where he’d look at his employer—at the only job he was then able to secure—say, “I’ve got to build this place into something,” and throw himself into the task.

It was his spin on the American Dream: You make your boss rich and he’ll take care of you. All Jack’s life he believed in that, no matter how many times the bosses got rich and he didn’t.

LAUGHS FROM THE DAY’S NEWS!

1936

Art: Jack Kirby

Lincoln Features Syndicate

Political cartoon

1939

Art: Jack Kirby

Lincoln Features Syndicate

Night and day he labored—a slave for Lincoln, producing more work than Elmo thought humanly possible. Most of the time, Jack wound up drawing at home in the Kurtzberg family flat, working on the kitchen table as his mother scurried around him, cooking and cleaning. Often, she’d be urging him to clear the table so she could set it for dinner, and he’d be pleading for another five minutes so he could finish one more panel. “It was even noisier there than at the Lincoln offices,” Jack recalled, “but at least at home there was someone to bring me soup.” The kitchen seat seems to have been a source of comfort to him. In later years, when he could easily have afforded a more conventional artist’s setup, he often opted for a straight-backed wooden chair, not unlike those from his mother’s kitchen.

Jack was so prolific that Elmo decided to try marketing several daily strips, all drawn by Kurtzberg in different styles and under different names. Jack Curtiss drew The Black Buccaneer, a swashbuckler strip. There was also “Cyclone” Burke by “Bob Brown.” That one was a cross between Smilin’ Jack and Buck Rogers. He even went back to drawing Popeye in a fashion . . . a knockoff by “Teddy” called Socko the Seadog.

Jack loved the diversity of the job as he vaulted from world to world, spending his mornings drawing pirates and his afternoons in outer space. He especially enjoyed doing political cartoons. As busy as he was, he always took out time to follow the news and to formulate strong, often prescient opinions. He was the first of his crowd to proclaim that a war against that Hitler fellow was in America’s future.

But he sure didn’t love the take-home pay. Elmo was unable to place most of the strips for long or at all, and not one of the promised bonuses ever materialized. It was yet another first in the life of Jacob/Jack Kurtzberg/Kirby: He could write, he could draw, he could create the best comics out there with a volume and speed that stunned everyone. But he couldn’t seem to make a deal that would turn his glorious creativity into great take-home pay. Either he’d work for men who didn’t know how to exploit what he gave them, or for men who did and wouldn’t share. Eventually, Elmo started downsizing and Jack, while continuing to draw the features that survived, redoubled his efforts to find someplace else to work.

But where? The top-end syndicates were impossible to crack, and the low-end ones like Lincoln paid close to nothing. There had to be some other place a guy with Jack’s imagination could go and get paid for writing and drawing comics . . .

And there was. The place was those new things they were selling on newsracks and in candy stores: comic books.

These comics started as reprints of newspaper strips. Someone would repaste the panels—not always in sequence—and the publisher would offer sixty-four pages in color for a dime. The magazines were so successful that all the popular strips were quickly locked up. That’s where all those aspiring cartoonists with the portfolios came in handy.

The work Jack did for Lincoln Features Syndicate was signed with a wide array of names, some of which were originated by others. In later years he remarked, “I was not only creating characters to draw, I was creating the guys who drew them.”

Samples of Kirby’s strips for Lincoln Features. Even Jack wasn’t sure which of these actually made it into newspapers.

1936–1939

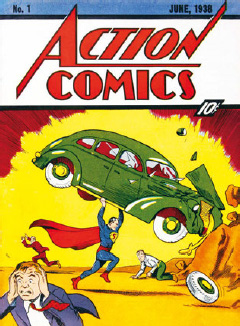

ACTION COMICS

no. 1

June 1938

Art: Joe Shuster

DC Comics, Inc.

If you wanted to publish comic books in the late thirties, you couldn’t get the rights to Wash Tubbs or Jungle Jim. What you could do was hire, for example, those two kids from Cleveland, Siegel and Shuster, to whip up the adventures of their new creation, Slam Bradley, just for comic books. Slam was just different enough from Wash Tubbs to not be actionable. Or you could pay young Bob Kahn (who’d later change his name to Bob Kane) a few bucks a page to draw his Jungle Jim facsimile, Clip Carson. Both appeared in magazines from the company that would soon be known as DC Comics.

None of the first comic book artists could match Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon for anatomy or Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant for sheer brilliance of drawing, even when tracing them directly. But many of the artists could tell a quicker, punchier story in pictures . . . and their work, designed for the comic book page, seemed more organic. Stories weren’t reassembled from daily strips, and therefore weren’t endlessly recapping what someone said six panels earlier.

The form hadn’t quite found itself. No one had yet really thought how to design a comic book page in any way other than to replicate the reconfigured newspaper reprints. But then, Jack Kirby hadn’t started drawing comic books yet.

He did in 1938, arriving at the studio of Eisner and Iger about the same time the first issue of Action Comics was arriving on newsstands. It featured that new strip Siegel and Shuster had created about a guy who could leap tall buildings in a single bound and jumpstart an entire industry . . . Superman. Jack would later call it, “The moment I knew comics were here to stay.”

The Eisner-Iger shop packaged comic book material for several publishers, some overseas. Jack felt instantly at home in the surroundings, and especially with the page format. Newspaper strips were small and confining, and they advanced their storylines in halting baby steps. Then as later, he thought in big pictures.

Eisner-Iger was a great place to learn. Kirby and the other artists swapped pointers, critiques, and ideas. There was also much to be gleaned from Will Eisner who, though only six months his senior, seemed like an adult and a solid role model.

Eisner was an elder statesman of the industry, having been in it for almost two years. Later, when he went off to write and draw The Spirit as a comic book section for newspapers, he’d be the other great innovator of the form—the guy besides Kirby leading the way, making comic books different from strips. When Jack first met Eisner, he was more impressive as a businessman. He had an office. He had a staff. He didn’t pay very well but he’d figured out the money end of comics for himself, a knack most artists (not just Jack) would never quite master.

There was instant mutual respect. Eisner envied Jack’s feisty determination and thought the man drew like he talked. He was powerful and direct, but also unique and quirky. There was envy of how Kurtzberg would attack a page, producing exciting visuals no matter what the storyline . . . and follow with another page and then others, all at an amazing clip. And he was so confident. If you asked Kurtzberg “Can you handle this?” the answer was “Yes” before he’d even heard what it was you needed him to handle. “Eight pages in a day? Sure, I can do that.”

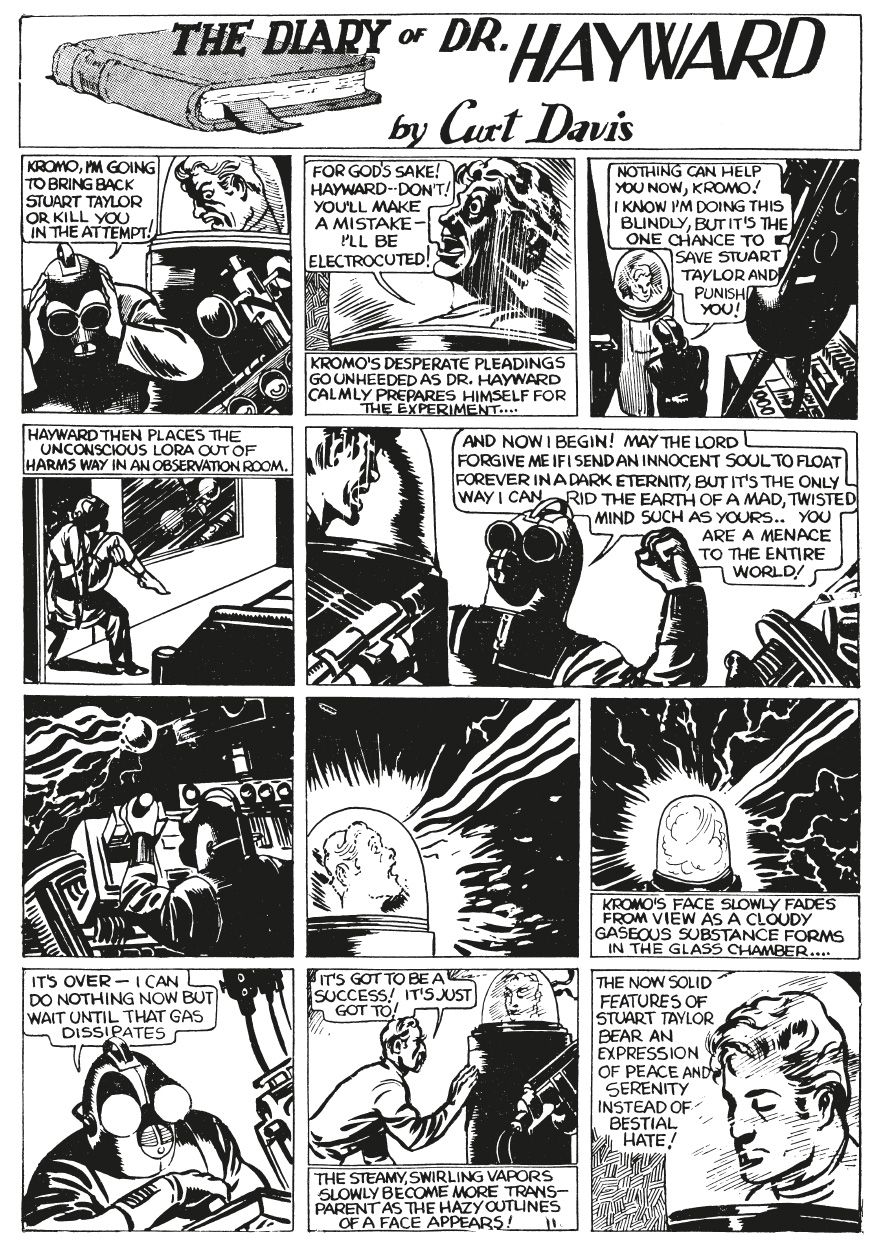

THE DIARY OF DR. HAYWARD JUMBO COMICS

no. 2

November 1938

Art: Jack Kirby

Fiction House

Will Eisner

Kirby called him, “My friend, teacher, and boss—not in that order.”

1941

Jack envied Eisner’s skill at assembly, his ability to run a company . . . even the way he dressed. Later, like everyone else, he would envy The Spirit. “The best comic of the forties,” Jack called it. “No question.”

Eisner and Iger ran a service called Universal Phoenix Syndicate that mainly supplied a British comics magazine called Wags. For them, Jack drew three features: The Diary of Dr. Hayward by “Curt Davis,” Wilton of the West by “Fred Sande,” and The Count of Monte Cristo by our old friend “Jack Curtiss.” The material was also seen in America in Jumbo Comics, published by Fiction House.

Off Jack went to other houses, showing samples, pitching new ideas. One publisher, just getting his first issues together, commissioned gobs of work, promising a high rate. Jack spent a month handing in pages, being assured that the financing to pay him was there. It was always just another few days before there’d be checks.

Of course, there were no checks . . . just, one day, an empty, hastily vacated office and no trace of the “publisher” or all the work Jack had done. In later years, when a script called for him to draw a scene of raw, agonized anger, it would be a handy moment to reflect upon.

Still, he never lost heart; not for a second. His Wilton of the West pages, shown at the Associated Features Syndicate, got him the job of producing a Lone Ranger imitation dubbed Lightning and the Lone Rider. Trying to sound like a cowboy star himself, he signed the strip “Lance Kirby.”

Lone Rider debuted in papers on January 3, 1939, to limited success. The first storyline was set in the old west, and then, without explanation, the continuity jumped to the present day. Didn’t help. The syndicate decided maybe Kurtzberg was the problem and replaced him with Frank Robbins, who couldn’t do anything with it either. (Robbins’s Johnny Hazard, much admired by Jack, would later become one of the longest-running newspaper adventure strips.)

All over New York, Kurtzberg scurried, trying to find someone to buy his artwork and ideas. He heard that Bob Kahn, an artist he’d met at Eisner-Iger, had sold Harry Donenfeld’s company a new strip called Batman. So Jack tried over there, only to get the same answer he heard so often: “Sorry, we have all the material we need.” Finally, at the suggestion of some other artists, Jack did what they all did sooner or later, usually sooner. He went over and enlisted in the sweatshop of Victor Fox, King of the Comics.

“They’d hire anyone over there,” Bill Everett once explained. “They didn’t even look at your samples. The mere fact that you had samples meant you were probably a good enough artist to work there.” Everett only lasted a few weeks, but Jack was on staff for months, many of them spent drawing a lackluster newspaper strip about Fox’s star attraction, the Blue Beetle. It was the first super hero he ever drew and easily the dullest, but one has to start somewhere.

BLUE BEETLE

Syndicated newspaper strip

January 1940

Art: Jack Kirby

Fox Features Syndicate

BLUE BOLT

no. 3

August 1940

Art: Joe Simon

Novelty Press

LONE RIDER

Syndicated newspaper strip January 1939

Art: Jack Kirby

Associated Features Syndicate

Fox paid low but the money was there, what there was of it. It was a place to get out of, and Jack tried like hell. At nights, he’d produce pages of The Solar Legion, a comics feature he’d sold to an entrepreneur named Bert Whitman who, in turn, sold it to Tem Publishing. Then Jack would put in a sixty-hour week working for “the King.” When Fox hired Joe Simon to supervise the writers and artists, the new editor was instantly impressed with Kurtzberg’s productivity.

Like Eisner, Simon was another seasoned veteran of the comic book industry. He’d been in it more than a year in fact, mostly drawing comics for a shop called Funnies, Inc. But before that, he’d worked as a newspaper art director, a photo retoucher for Paramount Pictures, and as a magazine illustrator, so he’d been around. He knew how to do comics, too. Simon even looked at an artist’s samples before he’d hire him.

Side by side, they made a most unusual picture: Simon was 6'3" and weighed in at 150 pounds. Kirby weighed about the same but was almost a foot shorter.

Joe was four years his senior and unlike Jack in many ways but like him in others, starting with their fathers’ professions: both tailors. Simon would later explain, “One of the reasons Fox hired me was because I was wearing a very smart suit that my father had made me. That was where Jack was at a disadvantage. My father made suits, but his father only made pants.”

Simon didn’t mind that Kurtzberg was moonlighting from Fox. How could he? He was moonlighting himself, doing a comic for Novelty Press called Blue Bolt, starring a space hero he’d created while at Funnies, Inc. In fact, Joe was way behind on his deadlines, and since Jack was so fast and eager for extra work . . .

In Blue Bolt, you see the team begin. The first story, done before he met Jack, was all by Joe. The second, published in an issue cover-dated July 1940, is signed by Simon alone, but some of the pages within were by Jack. By the fifth story, they’re clearly working on the same pages—mostly Jack penciling, Joe inking—and the first page is signed “by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.”

Kurtzberg was Kirby, now and forever. The change was no big deal for Jack, and it certainly wasn’t because he wanted to conceal his Jewish heritage—though if you wanted to see steam come out of his ears, suggesting that would make it happen. It was just a desire to sound like a professional. “Kurtzberg” didn’t sound like a famous writer and artist. “Kirby,” he thought, did.

Simon and Kirby. It had a nice sound to it.

As a team, they were a perfect fit. Joe was a good artist, but Jack was better . . . not only better than Joe but better than just about anyone. At least, Jack was faster and more willing to park his keister at the drawing table for long, marathon stretches. Then again, Jack didn’t like to ink and Joe didn’t mind it. Joe was also a genius (Jack’s opinion) at designing covers and opening pages, and making the product look professional.

Not that there was ever a finite division of labor. Sometimes they swapped functions and there would be plenty of jobs where neither man could tell quite where the other left off. To the eternal question of who did what, Jack had a simple answer: “We both did everything.”

True enough, but there was one area where Simon truly outstripped his partner—the business side. Joe knew when to stand and when to advance. He left Fox, his tenure having lasted an arduous three months, and set up shop in an office on Forty-fifth Street. Immediately, he was landing new accounts and urging Jack to come be full-time with him. No, said Jack. As Simon would explain, “He was making a lot more money with the work he was doing with me, working evenings and weekends, but it was all freelance. The Fox paycheck was steady and guaranteed, and he couldn’t bring himself to gamble on the freelance work being steady.” This was in spite of all the work they did for Novelty Press and Prize Comics and for the new company Al Harvey was starting up.

Simon was, like Eisner, that rarest of talents—an artist with some acumen. He could read a contract and negotiate good terms . . . skills in which Kirby was worse than merely deficient. More important, Simon knew how to converse with publishers, speak their language, and gain their trust. When Victor Fox met him, he’d hired Joe on the spot as his editor in chief. Soon after, Simon met with a publisher named Martin Goodman and was promptly offered the same title at an even better salary.

Goodman was of a breed rapidly approaching extinction: He was a publisher of pulp magazines. “Martin believed he had his finger on the pulse beat of the country,” recalled Don Rico, one of his later editors. “From where I sat, he was just a guy who knew how to shovel product onto the stands and make a buck. He usually arrived on the tail end of a trend. Martin got into pulps just as the pulps started to lose popularity.”

In the summer of ’39, Goodman’s line of pulps was in trouble with the Federal Trade Commission (he’d snuck in reprints without labelling them as such), and he was desperate for something else to publish. Hearing that comics were the coming trend, he issued Marvel Comics no. 1, its contents prepared by Funnies, Inc. Cover-featured was a fiery, crime-fighting android named the Human Torch, created, written, and drawn by Carl Burgos. Equally exciting was the Sub-Mariner, an undersea antihero conceived and rendered by Bill Everett.

Goodman’s line went by many names, of which Timely Comics was the most common. He soon added a second title—Daring Mystery Comics, which featured work by Joe Simon, mostly on a strip called The Fiery Mask. Then Goodman, eager to cut Funnies, Inc. out of the loop, hired Simon directly. The deal seemed like a good one, including profit-participation on whatever new books he launched. Joe offered to share it with Kirby. Jack liked the terms but still couldn’t bring himself to leave whatever feeble security the weekly pay from Fox represented.

Joe needed Jack as much as Jack needed Joe, so it was arranged for Goodman to pay Jack a regular salary. For its time, it was a pretty good salary, and when Goodman wondered, Why so high?, Simon assured him: Kirby was great and would produce so many pages, the weekly guarantee would seem like a bargain.

Jack had what he wanted. He joined Simon and from then on, for the next sixteen years, they’d work together. Until very near the end, only a little thing like World War II would separate them . . . and even then, not for long.

CHAMPION COMICS

no. 9

July 1940

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Simon

Harvey Publications

Probably Kirby’s first published cover.

MARVEL COMICS

no. 1

October–November 1939

Art: Frank Paul

Marvel Comics

CAPTAIN AMERICA

no. 9

December 1941

Art: Jack Kirby and Syd Shores

Marvel Comics