“Jack Kirby is definitely my favorite comic book artist of all time because his style is so signature. It’s clear when you see it that it’s him. That’s what art is about, that you have no doubt who made it. Kirby was an original. He got left out in the cold because he designed all those looks . . . and never got paid for that. He’s a bit of an unsung hero in that way.”

— NICOLAS CAGE, ACTOR

JACK WAS PRETTY MUCH back where he’d started: traipsing around New York, looking for work; only now it was even worse than when he’d been doing it in the thirties. Now he had a wife and kids and a mortgage, and the industry was collapsing, not expanding. World War II aside, it was the scariest time of his life. This was when the “out of work” nightmares really kicked in for him.

The companies that survived pleaded the necessity of slashing page rates, sometimes by half. Prize was still publishing Young Romance, and there was some work there for a while, but every time Jack turned in a job, it seemed, he’d bring home a little less per page . . . and more worries that even that income would soon dry up.

He looked for other kinds of employment—maybe writing paperback novels, maybe doing covers or interior illustrations. No luck. His skills only seemed marketable in one line of steadily diminishing work. If he could do anything else, he didn’t know what it was.

New ideas for comics, he had. Plenty of them. But as skillful as he was with stories and art, he was still weak in the area of salesmanship. Little of Simon’s ability to talk with publishers and “pitch” had rubbed off on his partner. Jack’s odd way of speaking didn’t help, either. He had a tendency to ramble from topic to topic, leaping about and leaving one sentence unfinished while he began three others. Even Roz, who was with him every moment he wasn’t out trying to get work or trying to draw what he did get, couldn’t always make sense of him.

As desperate as things got, however, there were some depths to which he wouldn’t stoop. He wouldn’t pay bribes, a not uncommon practice among some editors. One informed Jack he could have plenty of work at a decent rate as long as, ahem, a piece of that rate was kicked back under the table. Jack told him off, stormed out of the office, and took the train home, fretting that ethics had trumped common sense survival. “Payoffs were a particularly sore spot with Jack,” Roz would later explain. “But he was even angrier with himself the few times he gave in to them.”

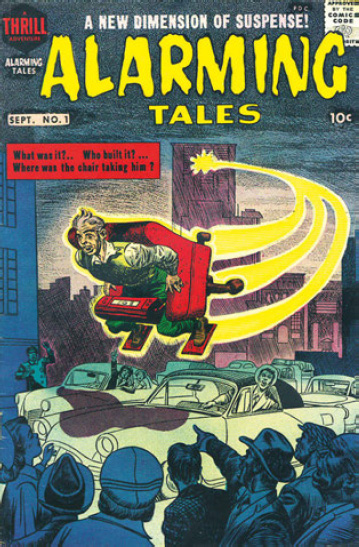

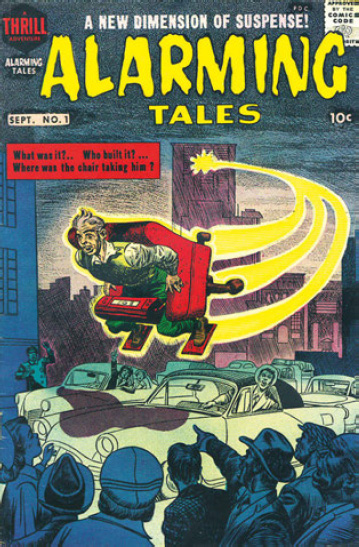

ALARMING TALES

no. 1

September 1957

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Simon

Harvey Publications

There was one other avenue to explore, but for the longest time Kirby avoided it. Martin Goodman’s company didn’t pay well but usually had assignments available. The trouble was that Jack had left there as the firm’s art director and star artist. It was humbling to think of going in and asking his former office boy, Stan Lee, for journeyman work. Also, as Kirby later explained: “I didn’t want Martin to think all was forgiven on the profits we never got on Captain America.”

Still, there was work there at Timely. And Jack needed work. A friend and fellow artist, Frank Giacoia, lived near the Kirbys in East Williston. He acted as go-between, and soon Jack was swallowing his pride and drawing war stories and westerns for Stan Lee. Stan was still in charge and thrilled to have Kirby on his books.

Stan took Jack up on his frequent boast of “Give me anything and I’ll make it sell.” He stuck Jack with Yellow Claw, a series derived from a book by Sax Rohmer, the creator of Fu Manchu. It is not known who wrote these issues—possibly Jack himself—but it almost didn’t matter. As he had at the Simon-Kirby studio and as he would with upcoming assignments elsewhere, Jack dominated the writing process. If someone else was engaged to produce scripts, Jack would give them plots and then rewrite whatever they handed in. Editors would often permit him this unusual power, and if they didn’t, he did it anyway.

Still, Kirby’s creativity and determination could not save Yellow Claw. It was hurriedly cancelled, and not long after, so was almost everything else the company was publishing. The problem was the same thing that had killed Mainline: Goodman’s distributor went out of business. The publisher scrambled and wound up making a deal with Independent News to disseminate his product.

Independent News was part of DC Comics, so it was a curious alliance of rivals, but not without its logic. Goodman had a rep for flooding (and sometimes in doing so, injuring) the marketplace. Jack Liebowitz, who still ran DC, was trying to nurse that marketplace back to health. He decided it was better to control Goodman than to let him play loose cannon. Independent took him on for distribution but severely limited the number of comics he could publish. Goodman wasn’t happy at the restrictions, but he was able to keep publishing comics.

This in turn limited the amount of work Stan Lee could commission. Ergo, no more work for Kirby. It was still that kind of year.

THEY TRIED EVERYTHING. WHEN Mainline was going under, Joe and Jack took all their leftover ideas and presentations over to DC. There was interest in only one of them . . . a comic about a band of men who’d each faced death but managed to survive. Thereafter, since they were living on “borrowed time,” they were ready and willing to take extraordinary chances.

Liebowitz had mixed feelings about welcoming Simon and Kirby back. “He hadn’t forgiven us for leaving him in the forties,” Jack once said. “But he respected us as guys who could generate hits, and with comics in so much trouble, he needed hits.” Liebowitz okayed a tryout for the book, which wound up being called Challengers of the Unknown. It would be published, but not for many months.

Things weren’t the same at DC. The production department, which ruled on matters of art direction, had definite ideas about what a DC comic should look like. Basically, they thought it shouldn’t look like a Jack Kirby comic. Artist Gil Kane, who had similar problems with the same people, would put it this way: “They kept demanding Jack strip his work of all the sharp edges and stylistic inventions that gave it its power and energy. Everything that was special about his art prompted the comment, ‘That’s not how we do it here.’”

Jack put it simpler: “They kept showing me their other books—books that weren’t selling—and saying, ‘This is what a comic book ought to be.’ I couldn’t communicate with those people.” Here and there, one can see signs of pure, energized Kirby peeking out from behind the DC “house look,” but not often. He was also anonymous in another way: the name Jack Kirby never appeared in a single DC book of the period.

Still, it was work . . . for Jack, anyway. The editors weren’t about to let Simon and Kirby have any editorial fees or power, and packaging as an outside supplier was out of the question. Their old nemesis Mort Weisinger was especially insistent on that, and it pretty much left Simon with nothing to do. Seeing no future in working for DC—and very little in doing comics at all—Joe decided to devote himself to his work for Harvey and to generating other, noncomics sources of income.

Kirby could do Challengers of the Unknown without Simon, and he did. A writer named Dave Wood provided scripts, which pretty much meant sitting with Kirby, hearing him spin off a plot, and then going home and typing it up. Jack rewrote whatever he was given anyway.

Challengers was a big enough hit to become an ongoing bi-monthly and the model for other adventure comics DC would launch. DC gave Jack other work, assigning him to Green Arrow, where he did what he could to build one of their duller super heroes into something. It wasn’t much. They also let him draw and occasionally write stories for their ghost/mystery comics. Jack did many, including one about a man finding the hammer of Thor and transforming into the God of Thunder . . . an interesting foreshadowing of triumphs yet to come.

But it wasn’t enough . . . not for Kirby. He drew for DC for thirty months, during which time he produced slightly over six hundred pages—or an average of twenty per month. For an artist who could produce that many in a week, it must have felt like temp work.

SHOWCASE

no. 6

February 1957

Art: Jack Kirby

DC Comics

SKY MASTERS

Presentation piece

Art: Jack Kirby and Wallace Wood

SKY MASTERS

Syndicated newspaper strip

April 26, 1959

Art: Jack Kirby and Wallace Wood

George Matthew Adams Syndicate

From time to time, Jack would help out his neighbor Frank Giacoia, ghosting on Frank’s newspaper strip, Johnny Reb and Billy Yank, wishing he had a strip of his own. Dave Wood had begun functioning as a kind of understudy to Joe Simon, proposing projects and partnerships. Together, Dave and Jack whipped up samples for several ideas, but no syndicate was interested. It would take a while, but the ever-trusting Kirby would eventually realize that Dave Wood was no Joe Simon.

Then came a break—or so it seemed at first. There was a man named Harry Elmlark who put together deals for syndicated strips, and he approached Jack Schiff, the editor of Challengers. Elmlark wanted a space strip created . . . a more modern riff on the old Flash Gordon genre. They were living in the era of Sputnik, with manned space missions just over the horizon, and it was time for a comic strip like that, he thought. Schiff put Elmlark together with Wood, who had a strip he and Jack had created, similar to what Elmlark was seeking. Elmlark told Wood and Kirby how to modify it, then placed their retooled version with a syndicate he also represented.

Kirby was jubilant. He was going to draw a newspaper strip called Sky Masters. Then he and his partners began to refine the terms and he stopped being jubilant.

Elmlark was to get a cut off the top. Kirby and Dave Wood would split the rest, but with all expenses—hiring an inker, paying the letterer, making stats, etc.— coming out of the artists’ share. It was a very poor deal for Kirby, but it got worse when Schiff began demanding a cut off the top as well. Kirby took the contract to a lawyer who told him, “You know, if this thing doesn’t sell to a decent number of papers, you could wind up drawing it for nothing. You could even lose money.”

Above and next page

SKY MASTERS

Syndicated newspaper strip

1958

Art: Jack Kirby and Wallace Wood

George Matthew Adams Syndicate

Kirby tried to refuse Schiff a share. He didn’t think Schiff had contributed enough to warrant his cut, and that it was yet another case of an editor extorting a kickback. That may not have been correct, but it’s the way Kirby saw it.

Wood went to Jack and said, roughly, “If we don’t give him a percentage, he’ll be furious with you and maybe with me.” Both were dependent on DC for most of their income, and neither could afford to make Schiff furious. So Kirby gave in on the point, making himself furious instead.

As the strip’s debut grew closer, they got a better idea how much it would gross. Kirby couldn’t believe how little he’d be making, especially considering he was already putting in more hours than anyone else. He and Wood had agreed that if it wasn’t worth either’s time, they’d drop the whole thing. By now Kirby wanted to drop the whole thing. Once again Wood said that if that happened, it would kill the strip and make Schiff furious. Again, Kirby buried his resentment.

Sky Masters was a troubled strip but a fine one. The writing was sharp and a lot of it was Kirby’s. The only way to get a script out of Dave Wood, Jack would later claim, was to give Dave the plot. And then what Dave would hand in would be unfinished and Jack would have to rewrite it, which of course added to his frustration that his cut was so small. He was writing or rewriting Challengers, too.

The artwork was exquisite, in no small part because Dave Wood had the idea to hire Wally Wood (no relation) to handle the inking. This Wood had proven his brilliance at science-fiction illustration when he drew for E. C. Comics. He proved it further, embellishing Kirby’s pencil art on Sky Masters and also on Challengers, making the incredible seem . . . well, credible. Fans would later debate if Kirby was well served by the overpowering Wood style, but no one would dispute that it was a great-looking comic strip.

Shortly before the great-looking strip debuted, Schiff decided he deserved a larger share. This time Kirby decided he could no longer refrain from making Schiff furious. He exploded, refusing to pay the editor any commission, let alone a higher one. Schiff exploded back. From there on, it went pretty much as Dave Wood had predicted. Suddenly, Jack was no longer drawing Challengers of the Unknown or anything else for DC, and was in deep financial trouble. Attempts to negotiate a settlement with Schiff only made matters worse.

Fortunately, Kirby had gained two other sources of income, one of which would actually last for a time. Stan Lee had called to say the freeze was over and he was buying again. The pay was low, but Jack was willing to take all he could get. At first, “all he could get” wasn’t “all he could do,” but that would change.

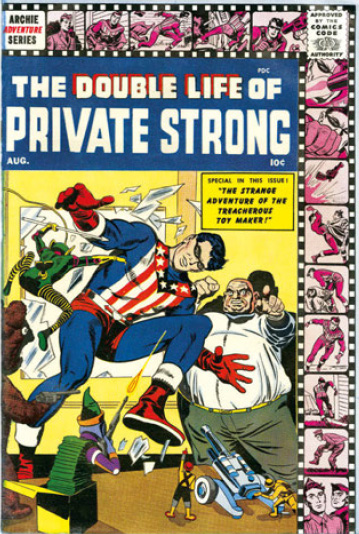

Then one day Kirby decided to go over to Columbus Circle in New York to visit the Archie company and see if they had any work for him. On his way there, he ran into Joe Simon, who was just coming from their offices, having recently made a deal with Archie publisher John Goldwater to launch two new super-hero comics for the firm. In fact, Joe was looking for someone to draw those two new books, Adventures of the Fly and The Double Life of Private Strong. The latter was a new twist on the Shield, the patriotic super hero who’d preceded and been eclipsed by Captain America.

Kirby worked on the first two issues of each. Actually, there were only two issues at all of Private Strong. Elements of his comic sounded to DC a lot like Superman’s, and when Liebowitz threatened legal action, Goldwater folded. The Fly buzzed around much longer, though Jack only helped design and initiate the character. This one was a reworking of an idea Simon had tried to sell years earlier called The Silver Spider. Joe and Jack changed the phylum, gave him flylike powers instead of spidery ones, and threw in some elements of Night Fighter, an unsold Simon-Kirby creation about a commando who walked up walls like a fly.

CLASSICS ILLUSTRATED

“The Last Days of Pompeii”

March 1961

Art: Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Gilberton Publications

With all the redraws demanded by editors, Kirby called it “the worst paying job of my entire life, including times I worked for free.”

And that’s how the Fly was born. The comic continued for years, but Jack left after the second issue and Joe left after the fourth. Goldwater kept complaining that the book didn’t look slick . . . like DC’s current product.

Simon devoted himself to Sick, a new and very successful imitation of MAD. It would be eighteen years before the two men would reunite, and then only for one book. “We didn’t plan it that way,” Jack noted. “But we didn’t see each other for more than fifteen years. There were times after that, I’d find myself missing Joe terribly.”

THE DOUBLE LIFE OF PRIVATE STRONG

no. 2

August 1959

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Simon

Archie Publications

ADVENTURES OF THE FLY

no. 1

August 1959

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Simon

Archie Publications

JACK SCHIFF SUED FOR breach of contract on Sky Masters. Kirby, getting questionable legal advice, thought he could convince a judge that he’d only signed the original contract under duress for fear of losing his work from DC. He was wrong about convincing the judge. The threats, if any, had not been explicit, and had been conveyed through Dave Wood, who didn’t dare cross his boss and back Kirby’s account. It also didn’t help that Kirby, with his wandering mind, faulty memory, and eccentric manner of speaking, was not a great witness. “Under oath, he couldn’t get his own name right,” Roz would remark.

So Kirby lost, and in many ways. He had to pay Schiff a modest sum the Kirby checkbook could ill afford and then keep paying Schiff commissions on Sky Masters, a strip that wasn’t taking in much by then and wasn’t long for the world. (It ended in February 1961.) Losing the suit also dashed any hopes Kirby might have had of getting back in at DC. Which meant he really had one and only one place to get work. “Shipwrecked at Marvel” was how he’d put it. There’d be a few miscellaneous other jobs—a story for Cracked, a few poor-paying jobs for the Classics Illustrated people—but for years to come and all through the sixties, Jack Kirby was stuck working for Martin Goodman’s company.

Which in turn prompted the perfect comment from Mike Sekowsky, one of DC’s star artists. Someone asked him years later who’d won the Schiff-Kirby lawsuit, and Sekowsky replied, “Stan Lee.”

STRANGE WORLDS

no. 1

December 1958

Art: Jack Kirby and Christopher Rule

Marvel Comics

SILVER SURFER

Private commission

1985

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott

Color: Tom Ziuko