“There was no ‘Marvel’ age of comics. It was a Lee and Kirby age. No matter how much the tots in us admired other artists, other writers, the highest massif of the Marvel pinnacle was tenanted solely by that two-headed monster. It is arguable only by idiot deconstructionists or parvenus that Jack Kirby and Stan Lee not only worked way far outside the traditions of the envelope that was comics, they tore it to shreds. They recreated an entire universe. they set a tone, a path, a vision that hungry talents other than theirs perceived . . . and tracked. But Kirby, above all the others, was the Nostradamus. He painted that Sistine Chapel ceiling of funnybook environment with a brush and a palette of colors everyone else—to this day—emulates. No praise is too much.”

— HARLAN ELLISON, SCIENCE FICTION GRAND MASTER

MARTIN GOODMAN’S COMPANY went by dozens of different names—some sort of tax dodge, Kirby said—but the comic book line was mainly referred to as Atlas back then. His other, more profitable divisions put out puzzle books and magazines featuring hard-boiled fiction for males and/or racy cartoons and/or photos of naked women. Some felt he only kept the comics going so Stan Lee would have a job.

That job wasn’t much. Working with almost no staff or budget, Stan assembled approximately ten comics a month. One or two were westerns, two or three were “teen” comics (Millie the Model, to name one), one was usually a love comic, and the rest were an odd kind of science-fiction/monster comic that appealed to the same audience that had flocked to see Godzilla, King of the Monsters! at Saturday matinees.

Kirby drew for all but the teen comics, usually handling at least the cover and lead stories. The rest of the freelance pool consisted of Steve Ditko, Don Heck, Dick Ayers, Paul Reinman, Jack Keller, Al Hartley, Vince Colletta, Stan Goldberg, and, occasionally, Gene Colan. Stan wrote most of the scripts, and what he couldn’t write he farmed out to his brother, Larry Lieber. Larry scripted many of the lead monster stories drawn by Kirby—stories like “Googam, Son of Goom” and “Fin Fang Foom!” “Fin Fang Foom!” was about a giant dragon dressed, for some reason, in a diaper.

In later years, Jack was of two minds about these stories. They were among the poorest-paying of his career, but he saw in them the clear antecedents of the Marvel Super Heroes. There was one story about a brute called the Thing, and several creatures named the Hulk. Beyond the names, there was an underlying sensibility: The “monsters” were not all monsters, the “good guys” were not 100 percent good, and the attainment of great power was not without its downside.

JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY

no. 62

November 1962

Art: Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko

Marvel Comics

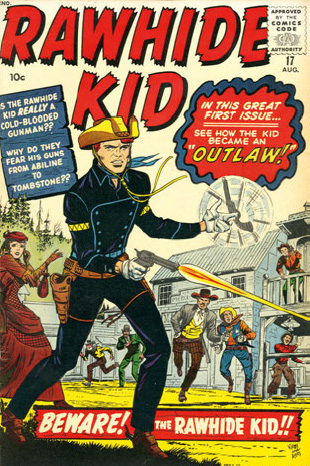

RAWHIDE KID

no. 17

August 1960

Art: Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Marvel Comics

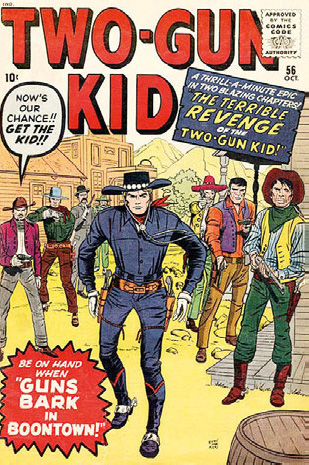

TWO-GUN KID

no. 56

October 1960

Art: Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Marvel Comics

Sometimes the plots came from Stan, sometimes from Jack. When Stan and Jack did a story together, they had a new means of collaboration. It was born of necessity—Stan was overburdened with work—and to make use of Jack’s great skill with storylines. Stan later explained it as follows:

“I’d be writing a script for Ditko to draw. Jack would come in to drop off a job he’d finished and he’d want another script to start on. I’d tell him, ‘I can’t get you one now. I have to finish Ditko’s.’ But so that Jack wouldn’t leave empty-handed, we’d talk out a plot and I’d send him off to draw it. That way, he’d have work, and after he handed the pages in, I’d write the dialogue.”

Sometimes Stan would type up a written plot outline for the artist. Sometimes, not. Later, some of the artists (including Kirby and Ditko) would insist that Stan had contributed very little—sometimes nothing—to the plots of the comics. Since he received the total writing fee and (usually) the total writing credit, that would be a sore point in years to come.

But at the time, everyone was happy just to have work and the “Marvel Method,” as it would come to be known, produced some fine comics. Lee’s dialogue was witty and filled with character. Place it over exciting visual storytelling by Kirby or Ditko and you had something very special.

This was evident first on Rawhide Kid, a long-running western comic that Lee and Kirby revamped in 1960. They then did the same with Two-Gun Kid and whipped up a new strip about a sorcerer named Dr. Droom for Amazing Adventures. Sol Brodsky, who then worked part-time helping Stan with production, detailed their dilemma in a 1975 interview:

“Martin was too quick on the trigger to cancel a book. One slight dip in sales and it was gone. He sometimes didn’t think content mattered. He cancelled Two-Gun Kid before he received sales figures [on the Lee-Kirby revamp]. He didn’t believe what Stan and Jack had done to it would make much difference, but it did. Sales shot way up. He started looking for a place on the schedule to bring it back.”

That was assuming he kept publishing comics. No one was certain if he would, and at times he wasn’t so sure. In later years, Kirby and Brodsky both recalled Goodman actually packing it in at one point.

Jack told of walking into the offices one day around 1961 and finding Stan weeping. The comic line had been discontinued. “They were taking out the office furniture,” Kirby recalled on more than one occasion. “I told them to stop. I told Martin we could turn the company around if he’d just hang in there.” There is no doubt Jack honestly remembered it that way. Other sources suggest his memory was overstating the desperation, the better to improve on a good story.

But if Kirby was exaggerating, it was only by a little: Goodman had already come close to shutting down his comic book division with the cutbacks and buying freeze of May 1957. That downsizing had involved actual furniture removal as well as great interoffice emotion, and was probably the scene Jack was recalling. Business had improved a bit since then, but had never reached any stage of stability.

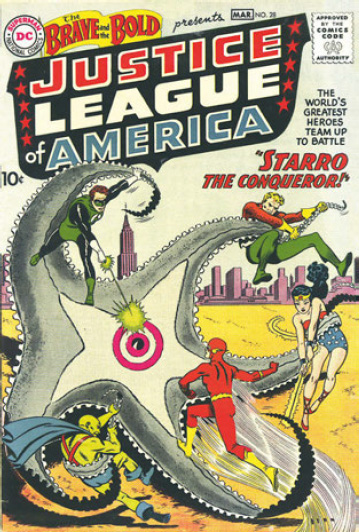

That Goodman kept at it had everything to do with the slow comeback of DC Comics. Even as Stan was allegedly weeping over a shutdown, DC was enjoying modest success with some super-hero revivals. One in particular—the super-team Justice League of America—seemed to suggest a coming trend.

That was all Goodman had to hear. Industry legend, sometimes recounted by Lee, holds that Martin learned of DC’s numbers from Jack Liebowitz during a golf date. Liebowitz, however, would later proclaim he never played golf with Goodman and insisted, “I’m sure I didn’t discuss anything with him about that, but everybody knew what the sales were.” Goodman sure did. He decided to postpone the return of Two-Gun Kid and instead directed Lee to come up with a super-hero team book.

And suddenly, way down at the end of the tunnel, there was light.

TALES TO ASTONISH

no. 34

August 1962

Art: Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Marvel Comics

THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD

no. 28

February—March 1960

Art: Mike Sekowsky and Murphy Anderson

DC Comics

SO ONE DAY, STAN LEE called in Jack Kirby, and between them the first issue of Fantastic Four came to be. It wasn’t polished or even all that coherent. But somewhere in there, there was a sense of beginning.

The origin story that Stan and Jack crafted detailed the story of four adventurers—Professor Reed Richards, Sue Storm, her younger brother Johnny Storm, and test pilot Ben Grimm. Launched into space as part of an experiment, they underwent incredible transformations when their craft was bombarded by cosmic rays. Cosmic rays and all forms of radiation, in those days of atom bomb testing and scares, would prove to be an all-purpose, one-size-fits-all origin device for any comic scripted by Stan Lee.

Returning hastily to Earth, the four discovered their new abilities: Richards could stretch, much in the manner of the classic super hero Plastic Man. This afforded the scientist a physical power in striking contrast to his sedate, intellectual personality. He called himself Mr. Fantastic, though in keeping with a coming dynamic that would emphasize character over gimmick, he would more often be called by his real name. Similarly, his fiancée Sue Storm, who received the power to disappear, would be more often addressed as Sue than as the Invisible Girl.

Her brother, Johnny Storm, could burst into flame, fly, and hurl fireballs. Perhaps inspired by how DC was updating its defunct super heroes of the forties, Lee and Kirby had resurrected and remodeled the Human Torch. Whereas the version created by Carl Burgos had been an android, the new incarnation was a young man whose personality was “hot-headed,” as per his newfound powers.

But the hands-down scene-stealer of the group was Ben Grimm, cursed by the radiation to become a misshapen being with a reptilian epidermis and awesome strength—the Thing. The character had his lineage in the monster comics that Jack was still drawing at the time, but Jack saw another point of origin: himself.

Above and following pages

FANTASTIC FOUR

no. 1

November 1961

Art: Jack Kirby and George Klein

Marvel Comics

FANTASTIC FOUR

no. 5

July 1962

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott

Marvel Comics

FANTASTIC FOUR

no. 7

October 1962

Art: Jack Kirby

Marvel Comics

Though Kirby identified with the character of the Thing, friends have noticed the uncanny resemblance on this cover between Mr. Fantastic and Jack himself . . . all the more intriguing because this was the only Fantastic Four cover Jack ever inked. Therefore, that’s exactly how he intended the character to look.

FANTASTIC FOUR

no. 10

January 1963

Art: Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Marvel Comics

Stan and Jack become characters in their own comic . . . hiding their faces as they encountered their master villain who always hid his own face.

FANTASTIC FOUR

Unpublished cover intended for no. 20

November 1963

Art: Jack Kirby

This one got as far as Stan Lee writing in the cover copy by hand.

THE INCREDIBLE HULK

no. 1

May 1962

Art: Jack Kirby and Paul Reinman

Marvel Comics

TALES TO ASTONISH

no. 35

September 1962

Art: Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Marvel Comics

“If you’ll notice the way the Thing talks and acts, you’ll find that the Thing is really Jack Kirby,” Jack once explained. “He has my manners, he has my manner of speech, and he thinks the way I do. He’s excitable, and you’ll find that he’s very, very active among people, and he can muscle his way through a crowd. I find I’m that sort of person.”

There would later be disagreement over the sequence of events that brought forth the new heroes. Lee would say he figured out the story and characters, typed up a plot outline (which still exists), selected Jack to draw it, and handed him the basics of the first issue. Kirby would say that wasn’t how they ever worked—that even on short, unimportant romance stories, there’d be a plot conference, and then he’d be sent off to pencil pages as he saw fit, with or without a typed plot. He’d say he came up with the characters and even point to how similar the origin was to Challengers of the Unknown.

Among those who worked around them at the time, there was a unanimous view: that Fantastic Four was created by Stan and Jack. No further division of credit seemed appropriate. Not on that, not on all the wonderment yet to come.

None of this mattered when the first issue reached newsstands on August 8, 1961. Creatively, it triggered a revolution in comic book storytelling, particularly in the areas of heroic fantasy. Financially, it began the ascent of Marvel—as the company would come to be known—from a tiny publisher to a massive, multimedia corporation and industry leader. More so than any release since Action Comics no. 1, Fantastic Four no. 1 changed the rules of the game.

The underpinnings of Fantastic Four may have resembled Challengers of the Unknown, but the new book was revolutionary in ways that Challengers was not. The FF characters—especially Ben Grimm, “The Thing”—had uncommon depth and personality, if not in their first issue then certainly as the book began to find its way. Even if Stan’s previous work had not suggested a flair for interesting, ongoing characters, his subsequent efforts, apart from Kirby, certainly would.

IT WAS THE SAME way with the next new comic they launched, though its success was not as immediately evident. Again, both Lee and Kirby would claim to have come up with the idea for The Incredible Hulk, though both cited Jekyll and Hyde as inspiration, as well as the Frankenstein book and movies.

The Hulk was a bridge between the monster comics Marvel had been producing and the super-hero books that were about to displace them. Perhaps that was why initial sales were disappointing. Still, there was something irresistible about the creature, gray-skinned in his first issue; green, thereafter. He was powerful and destructive but he was also more human than a lot of nonmonsters who’d inhabited comic books. Goodman would cancel the book after six issues, but the readers wouldn’t let this one go.

Goodman was, however, warming to the notion that super heroes might be his best wager. He had five ongoing monster/science-fiction anthology titles: Journey into Mystery, Amazing Adult Fantasy, Tales to Astonish, Strange Tales, and Tales of Suspense. He gave the nod to adding super-hero strips to the front of each. A smart move.

And so the Mighty Thor debuted in Journey into Mystery. Larry Lieber did the initial script, but the concept and plot, Stan said, came from him. Jack would later point to all the stories he’d done about gods (Thor, chief among them) walking the earth, and insist the series had originated with him.

Whoever’s idea it was, it was a good one—a new and fertile kind of super-hero franchise: gods, good and bad, warring with our planet as the battleground. It was a perfect way to bring forth an endless stream of intriguing, powerful characters without pausing for a contrived origin. Once you bought the Lee-Kirby spin on Norse legends, you were in. Their version of the God of Thunder had all the attributes of Captain Marvel, right down to the transformation in a bolt of lightning.

Later, when stories veered back toward Asgard, Jack would do some of his most striking ad-lib costume design and architectural rendering. Like so much of what he drew, it wasn’t deeply researched or logical, but it was drawn with such conviction and originality, few quibbled. You thought, Sure, that’s what Odin and his throne room must look like. As Chic Stone, who inked some of Jack’s best work on the strip, remarked, “Kirby could just lead you through all these different worlds. The readers would follow him anywhere.”

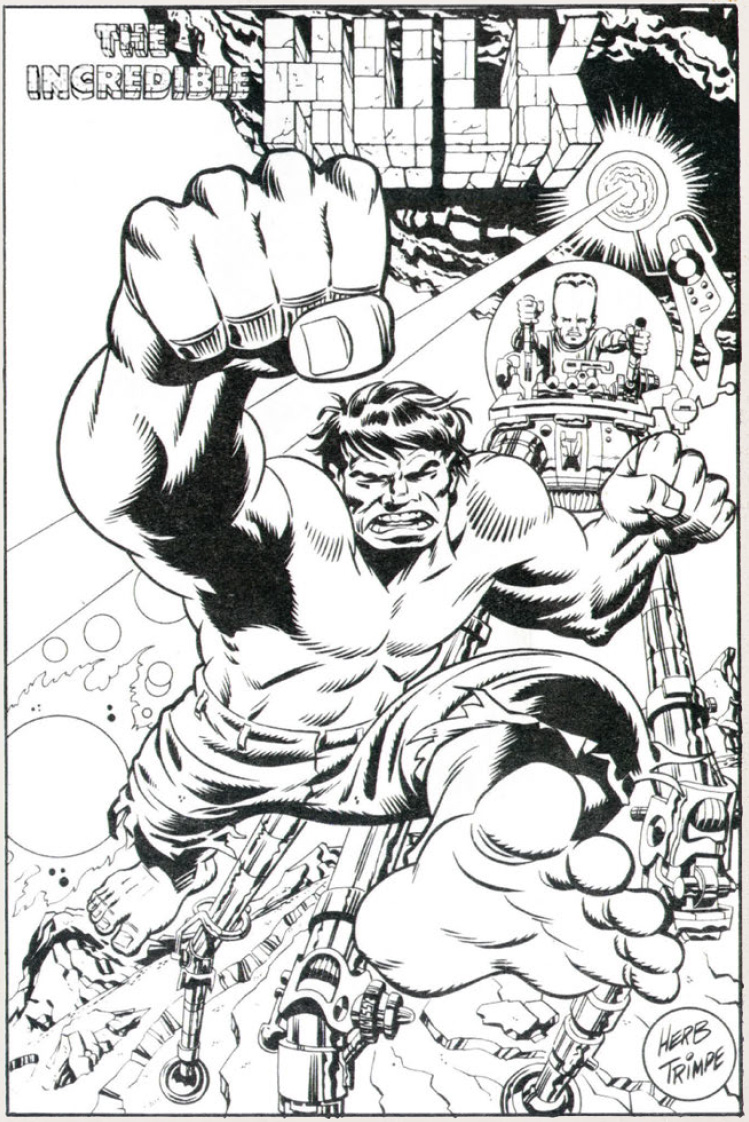

THE INCREDIBLE HULK

Gift to the author

1984

Art: Jack Kirby

Above and following pages

JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY

no. 83

August 1962

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott

Marvel Comics

AMAZING FANTASY

no. 15

August 1962

Art: Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko

Color: Stan Goldberg

Marvel Comics

THE SAME MONTH THOR debuted, a super hero was added to the book that had been known as Amazing Adult Fantasy. He was an unusual creation whose convoluted birthing process would cause considerable friction between Lee and Kirby. Both would forever claim to have come up with the idea for what would prove to be Marvel’s most successful character ever—the Amazing Spider-Man.

In later years, Stan recalled that in his search for new characters, his mind had drifted back to an old pulp hero: “I’d always loved the Spider. I also loved the name Hawkman, but of course DC had a character by that name. But thinking about Hawkman led me to Spider-Man. The minute I said it out loud—‘Spider-Man’—I knew we had to do it.”

Jack, however, maintained that he’d suggested the idea; that Spiderman (no hyphen) was an idea he’d once developed with Joe Simon . . . and he even had an old title logo design by Simon to prove it.

(What did Simon think? Joe agreed he’d developed a character by that name—the same character as the Silver Spider, which he and Kirby had turned into the Fly. But Joe insisted Jack was not involved in the character’s spidery days.)

Regardless, it was either Lee or Kirby who suggested doing Spider-Man, and Kirby began on the first tale of such a hero, similar in some ways to the character who would become famous under that name but different in many others. This one was, like Billy Batson and Captain Marvel, a young orphan who transformed into a muscular adult, in this case via a magic ring.

Jack was a few pages into it when the decision was made to abandon his work and start fresh with Steve Ditko as artist. Lee would say that this was because he decided Jack was making Spider-Man too heroic and muscular. Kirby would say this was because he was too busy and Ditko needed work. Neither account makes a lot of sense.

Kirby was always too busy. Besides, he wasn’t even trying to draw the kind of lithe, less muscled hero that Lee later said he’d envisioned. Jack was drawing something more like the Fly, and he only drew his Spiderman for a few panels on the discarded pages. They could have easily been redrawn. Moreover, neither account explains why the orphan became older, why the magic ring and transformation were dropped, why the origin changed, or why Ditko was told to design a completely new costume. Lee would say, “Jack could never draw Spider-Man the way I wanted him to look,” but Ditko drew a cover for the first appearance, and Stan rejected it in favor of one by Jack.

What would explain it all is if someone at Goodman’s was worried that what Kirby was doing was coming out too much like the Fly. (Ditko, in one of his few public statements on Spider-Man, later wrote that he recognized the similarities and so informed Stan.) John Goldwater at Archie was known to be quite litigious, as was Joe Simon, and Goodman may just have been afraid of a lawsuit. Neither Lee nor Kirby, however, ever recalled that as a motive for the major course correction.

However it changed, it changed. Lee and Ditko did the first Spider-Man story. Goodman hated it and cancelled the comic before receiving any sales figures. Subsequent reports, bolstered by reader mail and Stan’s enthusiasm for the property, would prompt him to launch a Spider-Man comic the following year—the same month, in fact, that he declared The Incredible Hulk a flop and cancelled that book. Talk about a guy who was slow to realize when he had a hit on his hands.

Spider-Man would quickly become Marvel’s biggest success. What Kirby contributed would be arguable and argued over, but Jack felt he’d contributed at least something, for which he received neither pay nor acknowledgment.

IN THE MEANTIME, Tales to Astonish got its super-hero feature in 1962: Ant-Man, a shrinking super hero who could communicate with insects. Kirby drew the first stories, asking all the time if they could be assigned to anyone else. Though his mettle never allowed him to concede he could not make an idea work, he came perilously close with Ant-Man, a character he found too ineffectual. “A super hero should stand for strength,” he later remarked. “No one fantasizes about being the size of an ant.” Years later, Jack would be both incensed and amused by a scholarly article that suggested that because he was not tall, the Marvel hero with whom he most closely identified had to be Ant-Man. In truth, it was probably the character he cared about the least.

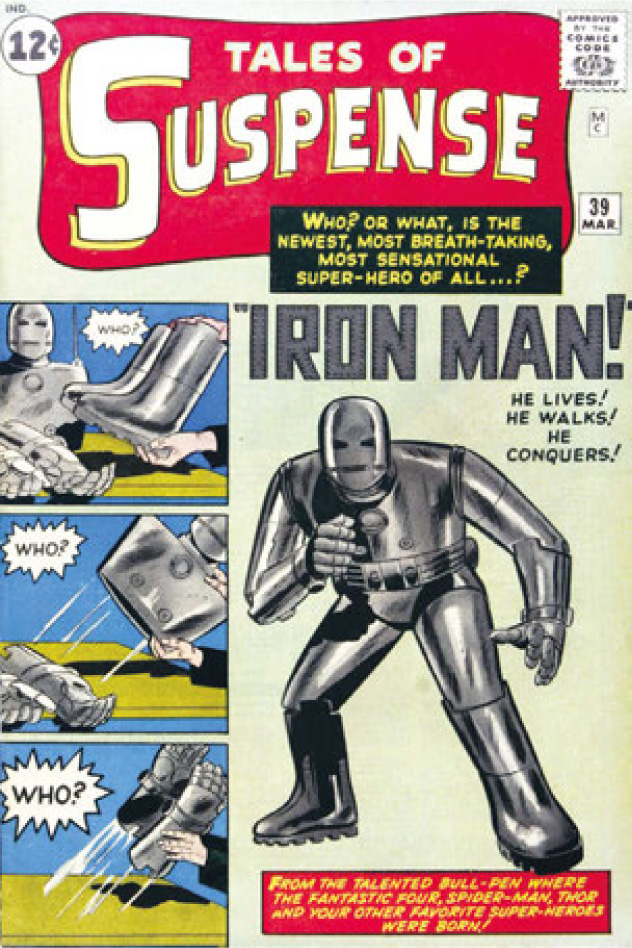

Solo adventures of the Human Torch were added to Strange Tales in 1962, drawn for a time by Kirby. And later, in 1963, Tales of Suspense received its super-hero feature: Iron Man, written at first by Larry Lieber and drawn initially by Don Heck. However, Lieber was working from a plot Stan had given him, and Heck was drawing from a cover and some concept sketches by Kirby. Stan wasn’t happy with the first story so he immediately turned the art chores over to . . . Kirby. Jack was the answer to all problems.

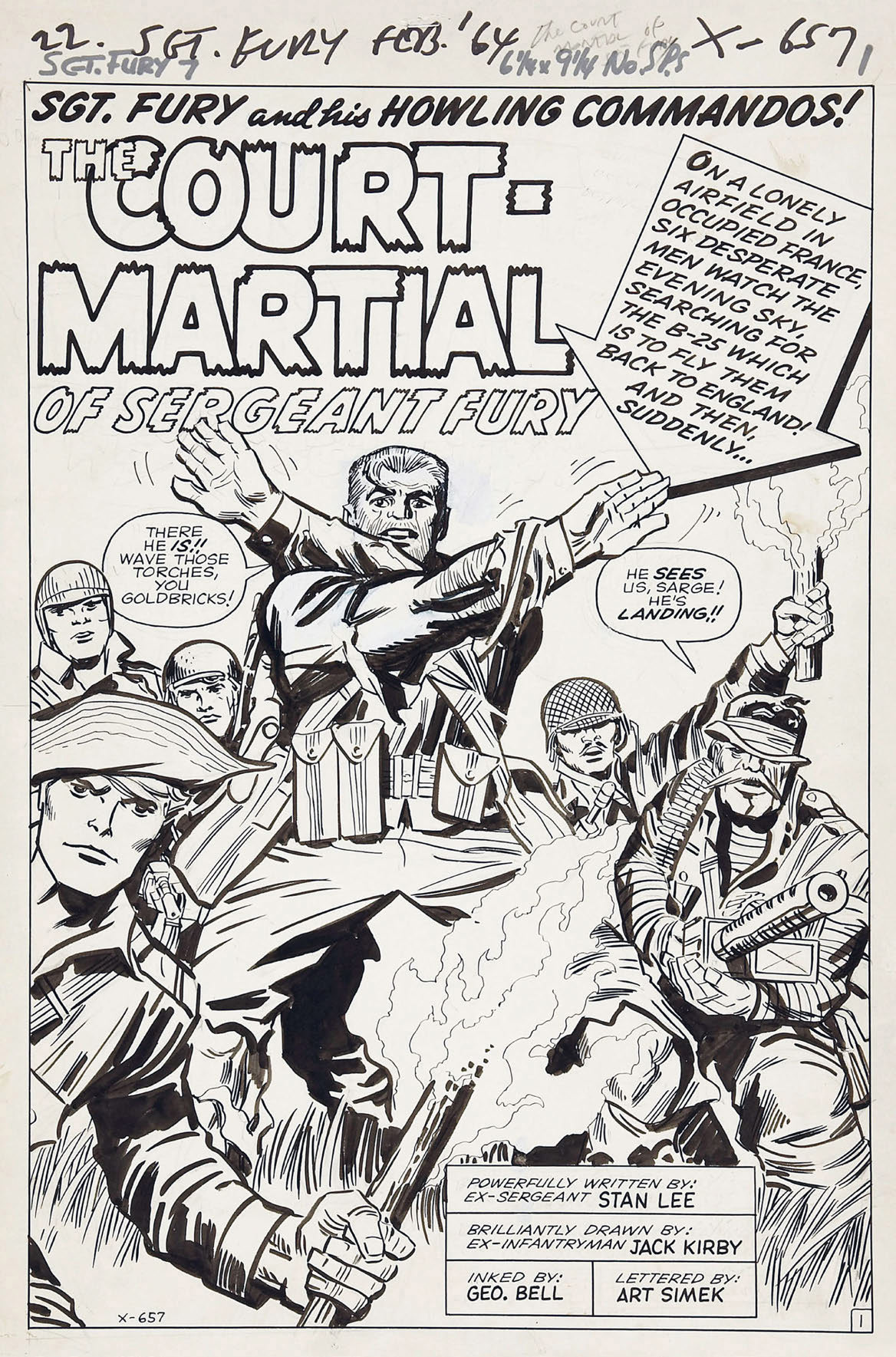

Other innovations followed. Goodman, with one eye on DC’s sales, thought war comics were due for a comeback. Stan had been telling him that he and Kirby had found a “new approach” to comics, a new way of making them exciting. The publisher wondered if this “new approach” would work for a war comic, and Stan said, “It would work for anything.” That was how Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos came about. From 1963 to 1964, Jack drew eight of the first thirteen issues, tapping into his endless cache of World War II memories and fashioning the lead character, the cigar-chomping Sgt. Nick Fury, on himself. Asked about it on one occasion, he explained, “Nick Fury is how I wish others saw me. Ben Grimm [The Thing] is probably closer to the way they do see me.”

TALES OF SUSPENSE

no. 39

March 1963

Art: Jack Kirby and Don Heck

Marvel Comics

SGT. FURY AND HIS HOWLING COMMANDOS

no. 1

May 1963

Art: Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Marvel Comics

SGT. FURY AND HIS HOWLING COMMANDOS

no. 7

May 1964

Art: Jack Kirby and “Geo. Bell”

(George Roussos)

Marvel Comics

THE AVENGERS

no. 4

March 1964

Art: Jack Kirby and George Roussos

Marvel Comics

Goodman still wanted a book like DC’s Justice League of America, so Stan and Jack gave him The Avengers. They gathered together (originally) the Hulk, Iron Man, Thor, the Wasp, and Ant-Man (soon to be Giant-Man) in his various sizes, forming a team of disparate, often bickering heroes. As with Sgt. Fury and other strips, Kirby drew the early issues before handing them off to another artist—in this case, Don Heck.

The most memorable early issue of The Avengers resurrected Captain America and placed him into the pantheon of Marvel super heroes. The star-spangled defender had endured the loss of Simon and Kirby back in the early forties, lasting until an industry-wide trend away from action heroes in the late forties. A brief revival attempt in the fifties had floundered—it wasn’t time for the super heroes to return.

Now that it was, back he came. Another resurrected Golden Age character, Bill Everett’s Sub-Mariner, ventured into chilly arctic waters and came across a block of ice containing the long-frozen form of the “real” Captain America. The Sub-Mariner ripped the frozen crypt free from the iceberg, and it was set adrift toward warmer waters. The Avengers chanced to find it, just as the hero was thawing out.

The science was ridiculous—Stan and Jack would each later blame the other for it—but the character’s impact was undeniable: Captain America was back in all his patriotic glory—and drawn by Jack Kirby! The hero quickly came to dominate the Avengers comic, and soon received his own strip in Tales of Suspense (1964).

Goodman asked for two more titles: a team that might replicate the sales success of Fantastic Four, and another acrobatic hero who might sell as well as Spider-Man. (“Martin was making progress,” Kirby remarked. “He went from imitating others’ successes to imitating his own.”)

For the former, Lee and Kirby came up with The X-Men in 1963, which introduced the concept of mutants into the Marvel repertoire, eventually to great advantage. It was another franchise—a simple premise through which dozens of new characters could be introduced and hit the ground running. The two central themes of Marvel superherodom converged once again: Having great powers could create great problems, and it was occasionally hard to tell the heroes from the villains. Some mutants were good, some were bad, many weren’t certain.

Again, the recollections of the two men would diverge as to how the strip came about, Stan claiming the concept originated with him, Kirby saying he had the idea. By now, that was the norm. So was Jack starting a book, drawing it until it had worked up a good momentum, then handing it off. X-Men would pass through many hands after it left his—some able, some not so able. The comic was even cancelled for a time before others would revive it, add new mutants onto the Lee-Kirby superstructure, and wind up with one of Marvel’s top-selling books from the eighties to the present day.

THE AVENGERS

no. 1

September 1963

Art: Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Marvel Comics

THE X-MEN

no. 1

September 1963

Art: Jack Kirby and Sol Brodsky

Marvel Comics

THE X-MEN

no. 2

November 1963

Art: Jack Kirby and Paul Reinman

Marvel Comics

THE X-MEN

no. 8

November 1964

Art: Jack Kirby and Chic Stone

Marvel Comics

THE X-MEN

Unpublished cover intended for no. 10

March 1965

Art: Jack Kirby and Chic Stone

For the acrobatic hero, Stan brought forth Daredevil in 1964, with Jack’s old friend Bill Everett as artist. Kirby did the early covers and seems to have aided with a few plot ideas, including the design of a “billy club” that the hero used to great, heroic advantage. Later, Jack’s old friend from Sky Masters, Wally Wood, would redesign the character into a more successful property, and others would build thereupon.

DAREDEVIL

no. 1

April 1964

Art: Jack Kirby and Bill Everett

Marvel Comics

STAN LEE WAS ON a creative high, energized especially by his collaborations not only with Kirby, but also with Steve Ditko on Spider-Man and a new magician character, Dr. Strange. The “Marvel Method” of plot first, then art, and then script, allowed Stan to produce hundreds of pages of comic book script per month, filling them with verbiage that was colorful and loaded with personality. It was even at times somewhat sophisticated, at least by comic book standards. He aimed just over the readers’ heads, and they loved it. Equally ingratiating was the chatty ambience of Marvel’s letter columns, cover copy, and house ads. The DC product of the day often read like your uncle was telling you a story. With Marvel, you were on a first name basis and your buddies—Smilin’ Stan and Jolly Jack—were there to entertain you.

He got the best out of his people, Stan did. He certainly got it out of Kirby and Ditko, encouraging styles and imaginations to run free. Not so long before, Jack had been lectured at DC for not conforming to the “house style.” Now, his was the “house style.” Jack was the guy other artists were told to emulate.

Don Heck, who was one of those other artists, would remark, “Stan wanted Kirby to be Kirby, Ditko to be Ditko . . . and everyone else to be Kirby.” Often, Stan would break in a new artist by having Jack do rough layouts for him, hoping it would be a learning experience. Sometimes, Jack taught more directly. Heck himself spent several evenings in the breakfast room of the Kirby home, being served coffee and danish by Roz while Jack coached him on how to make his art more dynamic.

Kirby’s output during this period was staggering, not just for quantity or quality, but for quantity of quality. Marvels carrying dates of 1962–64 featured 3,130 interior pages of Kirby art plus 285 covers—roughly the equivalent of a book a week. Often, on a comic where he did not do the interiors, he’d draw the cover and, in so doing, design a villain or other new character who’d appear within.

His value to the company was immense; his compensation was not. He later told of cornering Goodman in a hallway and reminding him how he’d weathered low pay when the company could not afford more. Rates were going up but not, Kirby believed, commensurate with profits. He also reminded Goodman of the old deal to pay Simon and Kirby 25 percent of the profits on comics featuring Captain America and any other new characters they created. Jack wasn’t even expecting that much on the new books, but he was expecting something.

Just what Goodman promised him, we’ll never know. Kirby later said it was significant, but it was also not on paper. Almost nothing about Jack’s working relationship with Marvel was on paper—not even, at the time, any delineation of what rights he had or was giving up to the material. Jack didn’t much like that, but he didn’t see an alternative.

So Jack hunkered down and kept working. From epic to epic he raced, and once he finished a drawing or story, it often went completely out of his head. Several times he forgot a character design, and it was necessary for the inker to retouch a costume so that it matched the previous issue. In stories continued from issue to issue, Jack sometimes forgot how the last chapter had ended, which led to the next story not linking up precisely.

He worked seven days a week, “chained to the board” (his term) in a dark, cramped basement cubicle he called “The Dungeon.” There were no windows, and when he became engrossed in a story, he usually lost all track of time. Roz would wake up at seven a.m., realize that Jack had never joined her in bed, and find him in the Dungeon, finishing his sixth page since the previous morning. Another artist producing work that detailed might have struggled to manage three a day.

The long hours were not without their effect, and in later years Roz would visibly shudder as she recalled a very real fear that Jack would literally work himself to death. Even when he had the flu, he would insist on dragging himself to the board, at least for a few panels.

He began to have problems with one eye—a condition that would be a constant concern. It would be years before it impacted his drawing, but he didn’t know that at the time and it worried him greatly. If he couldn’t see, he couldn’t draw . . . and if he couldn’t draw, he couldn’t bring home that all-important paycheck.

No one at Marvel knew about his slowly worsening vision. One day, he met with Stan to discuss an idea that had come up: a “super spy” feature built around Nick Fury, the sergeant from the war comic. This version would be set in the present day, and to differentiate it from the older Fury, Stan suggested giving the character an eyepatch.

Kirby was stunned. Here he was, worried about losing the use of an eye, and a character he viewed as his alter ego had just lost an eye. Life imitating art imitating life he called it.

He increasingly asked Marvel for some sort of long-term financial security—something with health insurance and maybe a pension. “We’ll discuss it,” they told him, but they never seemed willing to actually discuss it. Still, he spoke of “trying to build Marvel into something.” Still, there was a steadfast belief that the company’s financial success would trickle down his way.

SELF PORTRAIT

1966

Art: Jack Kirby

Wally Wood, who was publishing a new magazine called Witzend, asked Kirby to create a self-portrait. This is what Jack sent him.

STRANGE TALES

no. 138

November 1965

Art: Jack Kirby and John Severin

Marvel Comics

FANTASTIC FOUR REMAINED THE keystone book in the Marvel line, and moved from one-issue stories to multi-issue epics. It was the comic where great new characters were introduced, including the monomaniacal Dr. Doom, the supernormal tribe known as the Inhumans, and the character many consider the first black super hero in comics, the Black Panther.

And then there was the Silver Surfer.

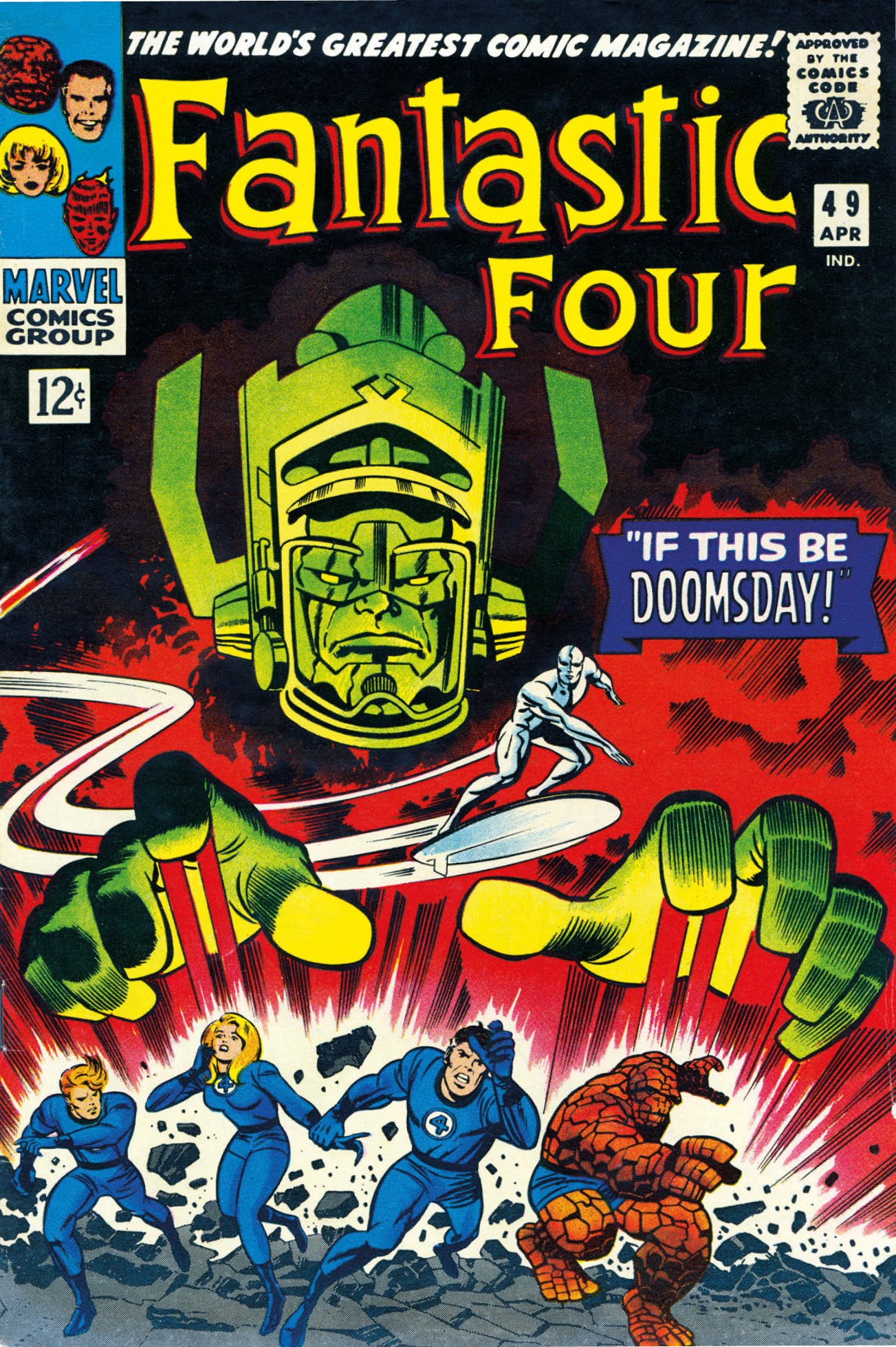

In early 1967, Fantastic Four featured a storyline that many regard as the peak of the Lee-Kirby collaboration: the tale of Galactus, an all-powerful being from another galaxy who feasted on planets, leaving them lifeless in his wake.

Articles would later claim that it all resulted from a four-word “plot” given verbally from Stan to Jack—“Have them fight God”—but it’s hard to see how Galactus, who consumed life instead of creating it, resembled either’s notion of the Almighty. Kirby had two allusions in mind. One was a concern prompted by all he read in science magazines, postulating a day when man might encounter beings from another planet and exchange technology. What, he wondered, if we encounter beings who don’t want to exchange technology? What if they just want to eat us?

The other concern was almost prescient with regard to Marvel. In the stock market section of the paper, Kirby was reading tales of corporate raiders who’d acquire a small company, drain it of its assets, and move on, leaving a hollow, inert shell. Goodman was getting feelers about a takeover, and that made Jack nervous.

FANTASTIC FOUR

no. 49

April 1966

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott

Marvel Comics

FANTASTIC FOUR

no. 84

March 1969

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott

Marvel Comics

FANTASTIC FOUR

Unpublished cover intended for no. 52

July 1966

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott

The first cover featuring a black costumed super hero required a different design, and in the process the Black Panther’s mask was redesigned to hide his face and race. Reportedly, this was to avoid outraging certain distributors who were expected to object.

Though deemed a masterwork among super-hero comics, the “Galactus Trilogy” (as it was later nicknamed) sparked considerable friction, at least from Jack’s end. As he drew the story, he decided to give Galactus a herald—someone to announce the impending arrival. Stan takes up the narrative . . .

“Jack may have come up with the name Galactus, or I might’ve. I probably wanted to call him Irving. The thing came back and I could hardly wait to start writing the copy. All of a sudden, as I’m looking through the drawings, I see this nut on a surfboard flying through the air. And I thought, ‘Jack, this time you’ve gone too far.’”

The nut on the surfboard was the Silver Surfer. In the story, he turned on his master, came to the defense of Earth, and a comic book superstar was born. One of the most popular of all the Marvel heroes had popped up where no one expected. Just like that.

The Surfer became a source of special contention between Lee and Kirby. Though he regarded the earlier Marvel heroes as primarily his concepts, Jack had at least discussed them with Stan before drawing their first stories. But the tale in which the Silver Surfer had debuted had been plotted and illustrated before Lee had even heard about the metallic guy hanging ten through the galaxy.

Both men became possessive about the character Stan sometimes cited as his favorite. A year or two later, Jack would be plotting a Fantastic Four that would fill in much of the Surfer’s backstory when he’d get some disturbing news. Marvel was launching an ongoing Silver Surfer comic and Stan was doing it with another artist, John Buscema. In fact, the first issue—already heading off to press—detailed an origin that Stan had devised for, as he called him, the Sentinel of the Spaceways.

Jack hadn’t been told about this, and it killed his own plans for the character and the story he’d already partially drawn. Lee’s origin also ran contrary to Kirby’s view of the hero. Jack saw the Surfer as a creature formed of pure energy, one who had never been human, which explained why he’d been roaming about the Fantastic Four comic, asking Earthlings to explain love and hate and other (to him) alien concepts. In Stan’s story, the Surfer had been a man on another planet who sacrificed human form to save the woman he loved.

That may have been the Surfer that Stan had been writing, but it wasn’t the one Jack had been drawing. Kirby especially didn’t like that he hadn’t been given first refusal on doing the new book. His idea had been taken from him in every possible sense.

By this time, his relationship with Stan had deteriorated in so many ways. Marvel was hot. Marvel was getting great press. An awful lot of it skewed in Stan’s favor, which may have been only natural. Stan was editor. Stan was the guy who welcomed reporters to his office while Jack was home drawing Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. Stan also gave a much better interview than Jack. He was witty, charming, and eminently quotable.

Above and following pages

The Inhumans

FANTASTIC FOUR SPECIAL

no. 5

November 1967

Art: Jack Kirby

Marvel Comics

“We need to fill some pages. Do some pin-ups of the Inhumans!” That’s what Stan Lee probably said to Jack, and Jack responded with pin-ups that were so fine, someone somewhere probably tore them out of his comic book and actually pinned them up. These are reproduced from Kirby’s file copy stats of the pencil art made after Stan indicated the copy placement for the letterer but before any inker got his hands on the art.

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

Stan and Jack attend a National Cartoonist

Society event in 1966.

To Jack’s complaints about pieces that identified Stan as sole creator—sometimes even of Captain America—Lee pleaded not guilty. He had no control over what reporters wrote. Once, when the Sunday New York Herald Tribune ran a major feature on Marvel, Stan made sure Jack was included in the interviews, but it didn’t matter. The published article still painted Stan Lee as the creative genius, and Jack Kirby as a buffoon who took dictation. Roz was so upset that the morning the paper came out, she woke Stan up at home to demand he do something about it.

As Marvel grew and Stan got busier, Jack was inventing all the plots for the comics they did together. He’d figure out an issue, draw it up, and write notes to Stan in the margins explaining what the heck was going on.

Sometimes Stan’s scripts would merely paraphrase what Jack had written. When they did, Jack would resent that he was receiving no credit or pay for what he was contributing to the writing.

Sometimes Stan would deviate wildly from what Jack had intended. Jack didn’t like that, either. He loved the stories he developed, and would often feel that Stan’s word balloons stripped some issue of its meaning or inverted a key concept. Jack especially resented it when Stan would take the first part of a story in a different direction than he’d intended. Not only would Jack feel his work was being harmed, but it also meant he’d have to redraw the last half (without pay, of course) to correspond.

Similar complaints caused the exit of several artists, Steve Ditko and Wally Wood among them. Both went off to jobs that could never have accommodated or sustained Jack. The Kirbys, with four kids and a steady stream of financial crises, were still just getting by on what Marvel paid.

The only comic book company that might have offered as much was DC, where Kirby was still persona non grata. Not only were several editors there hostile to the whole idea of Jack Kirby, but Jack had been told about an “understanding.” DC still distributed Marvel’s product, and there was an agreement, Jack was told, about not raiding one another’s talent pool. Marvel wouldn’t compete for artists by raising rates. DC, in turn, would not rob Marvel of the indispensable services of Jack Kirby. (Some artists did leave DC for Marvel, but not because they got more money.)

Jack began playing it safer. He would do simpler stories that Stan could dialogue without, he hoped, demanding redraws. He would also try to refrain from suggesting new characters with spin-off potential—or as Roz put it, “No more Silver Surfers until he gets a better deal.” It was agonizing for a creator like Jack, but he did it. At least, he tried to do it. When a new idea came to him, he jotted it down on a scrap of paper and, usually, lost it. Once, he got careless with a cigar, started a small fire in his workspace, and lost over fifty concepts—or as Roz put it, “A whole day’s work for Kirby.” Some new characters survived, however. Some lived to be rendered as fancy, full-color presentation drawings. Jack’s idea was to accumulate a pile of new concepts so that he could sell them to . . .

Well, that was the part he hadn’t figured out yet. There didn’t seem to be any potential customers.

Above and following pages

Presentation drawings for a proposed new version of Thor.

1968—1969

Art: Jack Kirby and Don Heck

Color: Jack Kirby

NOT BRAND ECHH

no. 1

August 1967

Art: Jack Kirby and Frank Giacoia

Marvel Comics

Lee and Kirby engage in a little self-spoofery.

Above and following page

TALES OF SUSPENSE

no. 80

August 1966

Art: Jack Kirby and Don Heck

Marvel Comics

As that better deal seemed ever more unlikely, Kirby’s relationship with Martin Goodman also deteriorated. Goodman was still selling comics in record numbers, and the characters were being merchandised. Jack’s plots and designs were on TV shows, his art was on toys . . . and he wasn’t seeing a nickel from any of it; just the occasional rate increase of a dollar or two per page. There was still nothing for him to live on if he became unable to draw.

Jack worried about getting his due. He heard that Bob Kane, the official creator of Batman, had made a million dollar deal with DC Comics. At about the same time, a writer there named Bill Finger had demanded a better deal, including higher rates and health insurance. Finger and other writers who made similar demands were quickly terminated. It was common knowledge in the business that though he hadn’t received the credit line, Finger had created as much of Batman as Kane had, maybe more.

The lesson was not lost on Kirby: Bob Kane, who’d been recognized as the creator of a successful property, had gotten rich. Bill Finger, who hadn’t, had gotten fired.

Then one day, Goodman sold his company. Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation acquired his publishing empire for a price Kirby described as “less than the value of Ant-Man alone.” Jack would point to the reported amount as proof that Goodman was a man lacking vision: “I could never get what I was worth out of him because he had no idea what his company was worth.”

The sale was executed with swift, almost surgical precision: One day, it was rumored; the next, it was a done deal. The only impediment had been Stan Lee.

The new owners didn’t know from Jack Kirby, but they’d read enough of those magazine articles to know that Stan Lee was the creative genius behind Marvel’s success. They would not purchase the company without him. As Jordan Raphael and Tom Spurgeon put it in their book, Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book, “Goodman encouraged Lee to sign a three-year contract so that he could close the deal. Lee did so loyally, receiving a raise in base pay and a promise from Goodman: ‘I’ll see to it that you and Joanie [Stan’s wife] never have to want for anything as long as you live.’” (If one believes Raphael and Spurgeon, the promise was quickly forgotten.)

Kirby’s lawyer contacted the new owners to tell them that Marvel had two creative geniuses. The response was along the lines of, “Don’t be silly. Stan created everything and the artists just drew what he told them to draw.” Roz recalled the attorney saying he’d even spoken to one high exec at Perfect Film who thought Stan drew all the comics, too.

FANTASTIC FOUR

no. 87

June 1969

Art: Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott

Marvel Comics

Program book for the San Diego Comic-Con

1983

Art: Jack Kirby

Via hindsight, Jack would later admit that this was the end of his Marvel tenure. At the time though, he couldn’t face that. He kept pressing for a better deal—or at least a renewal of his last, expired contract with Goodman. All he wanted was a little more money, some kind of long-term financial security for himself and his family, and an official acknowledgment of his status as co-creator. No more of this “Stan did it all” talk.

In the comic book industry of the eighties and beyond, that kind of working arrangement would be fairly standard, even for beginners. Artists who cited Kirby as their chief inspiration would become millionaires drawing comics he’d help start. But in 1968, it was far beyond out of the question. Not only was Jack refused, but he was lectured like a child with no sense of the world in which he lived. The company, he was told, had to do business the way it did. Any other financial setup and they’d have been bankrupt by week’s end.

Kirby didn’t believe that—not for a nanosecond. In fact, quite the opposite: The business, he told everyone, would have to change or that attitude would destroy it. He just feared it wouldn’t change in time for him to collect.

Then Perfect Film’s business folks just stopped talking to him or his lawyer. Goodman, who stayed on to run the company for its new owners, wouldn’t talk to him either. The only person he could speak to was Stan, who kept saying, “I have nothing to do with that.” Stan was busy jockeying for his own place in the new operation.

TALES OF ASGARD

no. 1

October 1968

Art: Jack Kirby

Cover sketch

Marvel Comics

Toys for Tots

Kirby (assisted by the author) contributed the key art for the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve’s annual Christmas charity drive poster.

1969

The Hulk

Unused poster for Marvelmania International

1969

Art: Jack Kirby

The Hulk

Poster for Marvelmania International

1969

Art: Herb Trimpe

Marvel Comics

HITTING BRICK WALLS LIKE that drove Jack to distraction, and from there to Southern California. In early 1969, the Kirbys moved west. The main reason was daughter Lisa’s asthma and her need to live in a drier climate. But Jack had another reason for hauling his battered drawing table cross-country. (It was the last thing the movers loaded on the truck in New York, waiting patiently as he finished an issue of Thor. And it was the first thing unloaded in California. They set it up, and Jack started drawing Fantastic Four while the moving men went and got the bed out of the van.)

Kirby had hopes that being close to Hollywood might bring him entry to the movie business. There was nothing concrete, but it had dawned on him that kids who’d grown up on his work would soon be old enough to run the studios. Maybe one of them would think, “Hey, let’s get that guy who did that comic I loved.” It was worth a try, at least. Film seemed like the next logical outlet for his creativity, and besides, he had to go somewhere.

Soon, he found one possible avenue of escape. Or maybe it followed him out from New York.

Carmine Infantino was a highly respected artist and an old friend. He and his brother had even worked in the Simon-Kirby shop at one point. Since then, he had become one of DC’s star artists, particularly on the super-speedster, the Flash.

DC had also been sold—to a company called Kinney National Services. Eventually, it would all morph into Time Warner, but in ’69, DC Comics had new corporate owners who were unhappy with their new acquisition. They had bought what they thought was the number one comic book company, and now Marvel had, by some measures, usurped the title.

A major overhaul of the company was needed, which meant new management. Infantino was that new management. Naturally, when you’re the guy in charge and the competition is thumping you, you want to hire away their key men. On a trip to L.A., Infantino met with Kirby and attempted to lure him over.

Kirby asked about DC’s two senior editors, Jack Schiff and Mort Weisinger. Schiff was still angry over the Sky Masters brouhaha. Weisinger’s antipathy dated back to the days when Simon and Kirby had refused to take editorial direction from him. In fact, one of Infantino’s first acquisitions was a weird new comic called Brother Power, the Geek—a Joe Simon creation. Weisinger had raised holy hell in the office and gotten it cancelled as of its second issue.

Infantino explained that a complete editorial restructuring was underway. Schiff, in fact, had retired two years earlier, and Weisinger would soon follow.

Kirby told of how he’d been led to believe there was an “understanding” between DC and Marvel not to raid talent, especially him. It flowed, did it not, from the fact that Independent News (i.e.: DC) distributed Marvel’s wares?

Not a problem, Infantino said. The two firms were no longer in business that way. Perfect Film’s holdings included a magazine distributor, and now that they owned Marvel, the deal with Independent had been allowed to expire.

The turn of events thrilled Kirby, but he was still hesitant . . . not quite ready yet to give up on Marvel. “Take your time,” Infantino said. The door was open.

Jack worked some more for Marvel and fought some more with Stan. There were more articles about how Stan had single-handedly created all the Marvel heroes. There were more pages that had to be redrawn because Stan would decide he wanted something different from what Jack had penciled. Stan thought Jack was getting sloppy with his plotting. Jack thought Stan was getting sloppy with his dialoguing.

There were other tensions, including a dustup over the Silver Surfer comic that Stan had been doing without Jack. The book wasn’t selling, and Stan assigned Kirby to do one issue to launch a new direction. This rekindled anger over how the character had been removed from his creative purview.

Stan’s theory was that the Surfer had not worked as a lead character because he was too much the pacifist. He should be more powerful and aggressive, Lee reportedly told Jack. And they intended to rename him “The Savage Silver Surfer.”

This was, to Kirby, an utter inversion of how he saw the hero, but he saw no reason not to give Stan what he wanted. In the story he crafted, the Surfer, previously a character of infinite peace with a love of mankind, vowed to make the world aware of his power and to battle them on their own terms. A few months later, when it was announced that Kirby was joining the competition, some readers who’d been unaware of the behind-the-scenes battles wondered if the Surfer hadn’t been speaking for Jack Kirby, albeit through Stan Lee dialogue.

Above and following image

SILVER SURFER

no. 18

September 1970

Art: Jack Kirby and Herb Trimpe

Marvel Comics

ALL THIS TIME, KIRBY was working without a contract. The old one with Goodman, which just called for a certain amount of work for a certain amount of money, had expired. Everyone at the new Marvel was just too busy to address his need for a new contract.

Finally, the first week in January 1970, a contract arrived in the Kirby mailbox—the new owners had new lawyers and the new lawyers had new demands. Although the terms under Goodman’s ownership had not been good, these were worse—no raise, no credit, not even any security. Marvel could do just about anything they wanted to him, including fire him whenever they felt like it. If he signed, he could never sue them for anything they’d done to him in the past or anything they’d do to him in the future.

There were other troubling clauses, each more onerous than the previous, so signing was out of the question. Jack couldn’t do that to himself, couldn’t do that to his family. He got his attorney involved, but Perfect Film/Marvel still wouldn’t talk to his attorney.

Then a lawyer or exec from Perfect Film called Jack directly. This is Kirby’s account as he described it in 1970: The caller asked when they’d be receiving the signed contract. Kirby said he needed changes. The caller said there would be no changes; take it or leave it. Sign it or get out.

Jack protested: He was too important to the company to be treated this way. The caller told him he was nuts. Stan Lee created everything at Marvel and they could get any idiot to draw up Stan’s brilliant ideas. At least, that’s how Jack would remember the conversation.

Kirby hung up on him, phoned Infantino, and changed companies.

The comic book universe trembled.

Darkseid

Unused page for New Gods

1971

Art: Jack Kirby