“I admire Kirby’s skill at stirring people, at getting them to drop the habit of skepticism and suspend disbelief. He was a contemporary Homer, spinning tales that entertain and that function as allegories about courage, the battle of good and evil, and the willingness to dream. They illustrate extremes of possibility, and if most of us can’t perform superhuman feats, or wipe out crime in our spare time, we can access some of the daring and pluck Jack’s heroes display, and become heroes of our own lives.”

— DAVID COPPERFIELD, ILLUSIONIST, FROM HIS INTRODUCTION TO THE MISTER MIRACLE COLLECTED EDITION

JACK WAS NEVER THAT happy at DC. Like everything else he did, he did it with maximum effort, but DC wasn’t where he belonged. It wasn’t his company or his style. Some in the office thought as they had in 1956—that a DC comic shouldn’t look like a Kirby comic.

Seeking to avoid another situation like he’d had with Stan Lee, Jack set a condition: He would work with a writer who’d provide a full script—all the plot, all the words up front—or he’d write the script himself. What he would not do is plot and draw a comic for someone else to dialogue. That had long since stopped working for him, both professionally and creatively. “If you don’t fill in the balloons,” Jack explained, “they don’t give you any credit for writing.” He also wanted his stories to remain his stories and not be inverted by someone else.

Jack Kirby filled in the balloons on most of what he did for the remainder of his career, often in a florid, theatrical voice that did to linguistics what his art had always done to the rules of anatomy and physics. Some loved his verbiage. Others hated it. Some who’d loved his work with Stan were just plain bothered by the difference. They wanted him back on Fantastic Four . . . or at least doing comics that read the same.

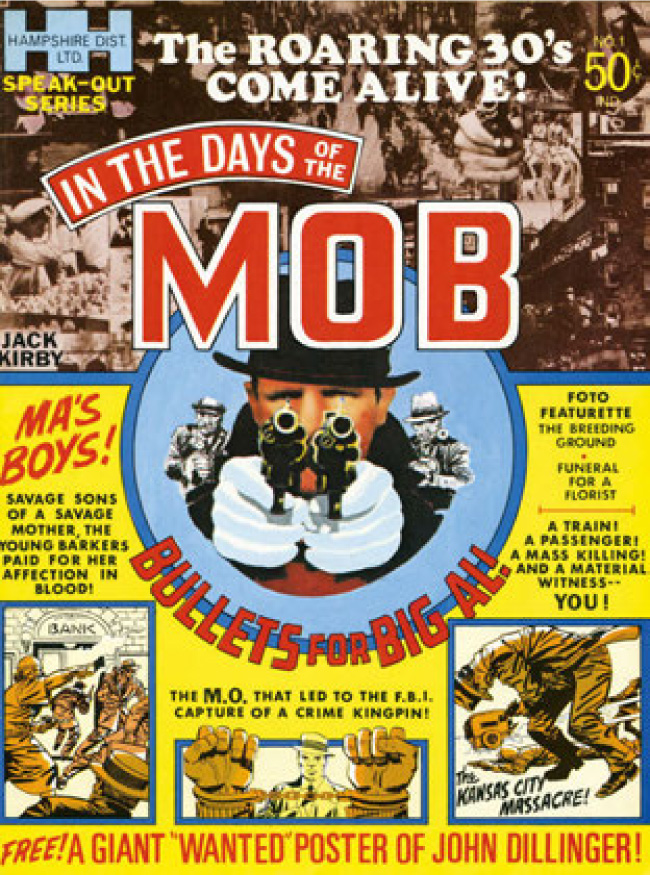

Having escaped Marvel, Jack also wanted to get away from cranking out comics of conventional size and subject. He thought he had more to say than he could in superhero comics. He also thought that package was doomed. The distribution methods by which comics then reached consumers certainly seemed to be. DC needed to try new formats, he said, suggesting several including slick magazines and graphic novels, as well as closed-end series that would later be collected in books and kept in print. Almost everything Jack proposed would later become viable, but at the time, DC was entrenched in one particular route to market. His second year there, they did let him do two magazine-format books on the lowest-possible budget, but canceled the whole endeavor before they even went on sale.

IN THE DAYS OF THE MOB

no. 1

Fall 1971

Art: Jack Kirby and Vince Colletta

Hampshire Distributors (DC Comics)

TRUE DIVORCE CASES

Unfinished page for proposed magazine.

1971

Art: Jack Kirby

In his first year, he started as writer/artist of Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen. The story that circulated was he’d said, “Give me your worst-selling book and I’ll make it your best-selling book.” Jack did talk like that, but Jimmy Olsen wasn’t their worst-selling book.

What did happen was that he was invited to pick any current comic and do whatever he wanted to it. That was how little the company was committed to anything it was then publishing. Jack gave the line the once-over and didn’t see one he wanted. But then Jack was never comfortable taking over someone else’s characters, displacing another voice with his own.

SUPERMAN’S PAL, JIMMY OLSEN

no. 141

September 1971

Art: Jack Kirby and Neal Adams

DC Comics

SUPERMAN’S PAL, JIMMY OLSEN

Unpublished cover intended for no. 133

October 1970

Art: Jack Kirby

Above and following image

SUPERMAN’S PAL, JIMMY OLSEN

no. 143

November 1971

Art: Jack Kirby, Vince Colletta, and Murphy Anderson

DC Comics

Above is what came off Jack’s drawing table. Vince Colletta inked everything but Superman and Jimmy Olsen, and the page was then given to veteran DC artist Murphy Anderson to finish. That meant bringing the characters more in line with “accepted” company interpretations, which were largely in the style of artist Curt Swan. Jack wasn’t happy and a lot of readers weren’t, either.

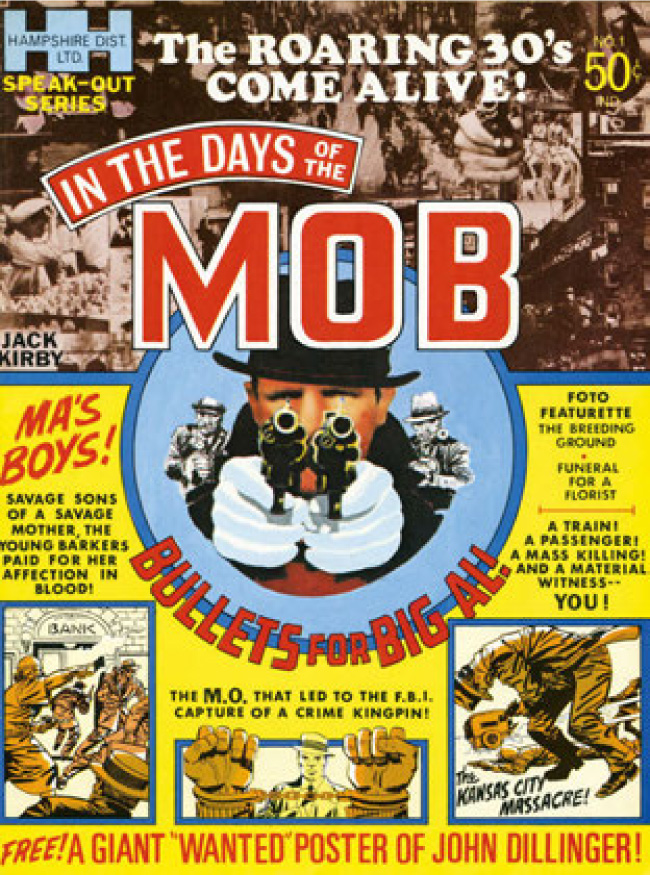

THE FOREVER PEOPLE

no. 1

February 1971

Art: Jack Kirby and Frank Giacoia

DC Comics

DC insisted, so he said, “Give me whatever book doesn’t currently have someone assigned to it.” He hated the thought of kicking a fellow professional off an assignment, especially if the guy’s income might suffer for it. At times, he’d even endure substandard inking on his art because, after all, that inker might need the job in order to feed his family.

As little as Kirby belonged at DC, he belonged less on Jimmy Olsen—a sappy comic about a young reporter who associated with the Man of Steel. The idea of Jack retooling Superman had been suggested, most likely to piss off the hero’s outgoing editor, Mort Weisinger. However, Olsen seemed like a place where Kirby could demonstrate what he’d do with the property.

The trouble was that Superman was DC’s most valuable asset. In later decades, the company would not only tolerate but encourage different interpretations of that asset. But back then, they fretted that Jack’s renditions of Jimmy and his pal didn’t look right. It was like, Give us a new Superman, but make sure he looks and functions like the old one. Jack’s version didn’t, so other artists were brought in to redraw the book’s principals, making for an odd mix of styles on every page: old-style non-Kirby heroes in a new-style Kirbyesque world.

The first Kirby issues sold through the roof, then numbers began a sluggish decline. Jack thought the problem was that readers, as proven by the initial interest, wanted his take on Superman. Due to the retouching, they weren’t getting it. The office consensus was that Jack’s stories were too unusual and disconnected—and they were odd, especially for that book. They ranged from a visit to a planet in a basement where everyone based their lives on monster movies from Earth . . . to a two-issue guest appearance by insult comedian Don Rickles. One Rickles cover had a sales line that cartoonist Scott Shaw! hailed as the greatest ever on a comic: “Kirby says, ‘Don’t ask, just buy it!’” That pretty much summed up Jack’s run on Jimmy Olsen.

EVEN BEFORE THEY LET Jack leave Superman’s Pal in 1972, he’d begun his major effort—a new universe of characters, pulled mostly from that stack of ideas he’d withheld from Marvel. He imagined up a new order of “gods,” a second generation to the kind he’d left behind in the Thor comic. In this new mythology, they dwelled on a planet that had split asunder. Thereafter, the good ones lived (or left for Earth from) a world called New Genesis. The bad ones inhabited the dank and foreboding Apokolips, the domain of an intergalactic Hitler known as Darkseid.

The überstory weaved through three bi-monthly titles and would have been in more had Jack gotten his way. It was another “franchise,” another way to unleash a bevy of characters in volume, and he foresaw endless possibilities.

THE NEW GODS

no. 1

February 1971

Art: Jack Kirby and Don Heck

DC Comics

THE NEW GODS

no. 7

February 1972

Art: Jack Kirby and Mike Royer

DC Comics

THE NEW GODS

The Glory Boat

No. 6

December 1971

Art: Jack Kirby

DC Comics

Pencils prior to inking

The Forever People featured the teenage gods, patterned after the youths that Kirby was observing all around him. In the midst of the Vietnam era, Jack was wholly on the side of those opposing Richard Nixon and the ongoing military action. He saw idealism, passion, and a better future in them and sought to infuse his Forever People with the same hopes, the same sense of responsibility at inheriting a world made dangerous.

The New Gods was the cornerstone title, focusing mainly on Orion, a warrior of New Genesis but also, as would be revealed, the estranged son of the master villain. Just a few years later, Star Wars would be the grand hit of Hollywood—and some of Kirby’s readers noted similarities. In New Gods, Orion had called upon a power called the Source in confrontation with his father, Darkseid. In Star Wars, Luke Skywalker called upon a power called the Force when he battled his father, Darth Vader. Kirby would not suspect plagiarism, but would fume that he had been unable to get his version made into a movie. Star Wars, he felt, had proven what a good, commercial idea it was.

Lastly, there was Mister Miracle, the super escape artist, who was inspired by a previous career of Jim Steranko, a “new generation” comics creator who’d become a Kirby friend and champion. But it was also inspired by Jack’s own feelings of confinement in his own career, and his eternal grasping for some way of breaking free. A few issues in, Miracle got a lady friend who’d later become his bride . . . the beautiful, bountiful Big Barda. A woman of spectacular physique, Barda was based on a Playboy layout of singer Lainie Kazan. At least, that’s where the visual came from. The spirit and personal strength were pure Roz.

Jack had intended to begin the books, pass them on to others under his supervision, and move on to bigger ideas. Infantino, however, wanted Jack to stick with the titles so he did, turning them into the foundation of an intense and highly personal epic. For reasons unknown, the umbrella title became “The Fourth World,” or sometimes, “Kirby’s Fourth World.”

Proud as he was of his world, Kirby sweated its reception. Some readers found it too sprawling, with new concepts introduced at a dizzying clip. The operatic dialogue put some readers off as well, but early sales were encouraging. The trouble was the books weren’t likely to be the Marvel-destroying hits that so many were expecting of him.

Just when Jack thought he was finding an audience, DC had a major price hike, its comics rocketing from fifteen cents apiece to twenty-five. That was a huge increase to buyers in 1971. Martin Goodman undercut with a twenty-cent price tag on all Marvels and better terms for distributors. Sales across the DC line plummeted—a brilliant chess move by Goodman. (But it didn’t negate problems he was having with the new owners. Soon after, he was squeezed out of his own company.)

MISTER MIRACLE

no. 1

March 1971

Art: Jack Kirby and Vince Colletta

DC Comics

MISTER MIRACLE

No. 4

October 1971

Art: Jack Kirby and Vince Colletta

DC Comics

Big Barda

Pencil sketch

1980

Art: Jack Kirby

The Demon

Sketchbook drawing

1981

Art: Jack Kirby

After months of dwindling sales, DC surrendered and dropped the price to twenty cents. Some books began to recover, but not Jack’s. His was a wide and complex—to some, confusing—narrative, and once you dropped out, it was tough to get back in. He had produced pilot issues for two new titles he wanted to edit with others doing the writing and drawing, but DC decided they wanted him doing the new titles instead. New Gods and Forever People were “suspended” (read: canceled) and Mister Miracle soon followed. Jack was crushed. “One of the worst days of my life,” was how he described the day of the call axing the first two. At least for the time being, his Fourth World would be an unfinished symphony, a novel without its final chapters.

The two new books were Kamandi, The Last Boy on Earth and The Demon. Neither was quite his métier, but they ventured where DC thought the market might be heading.

Kamandi was Jack’s spin on Planet of the Apes, a movie he’d heard much about but had not seen. Asked for something to parallel that film, Jack conjured up what was left of Earth after a good, old-fashioned nuclear holocaust and populated the world with a young human protagonist and a lot of people with animal heads. The book was a modest success that would continue until Jack left DC and for a while thereafter—not an industry-changer, but not a flop either.

The Demon was a horror book to the extent Jack Kirby could do a horror book. Despite the title character’s grotesque appearance, it was a work of power and energy and it came with a whole new Kirby mythology, this one derived from Merlin the Magician by way of King Arthur. Readers lost interest early and it was gone in sixteen issues—another blow to Jack’s spirit and his rep.

DC management was in grand panic to find something that would sell. The old distribution machine was broken, and the ever-diminishing number of comics the distributors could sell were mostly Marvel’s. Every time Jack got off the phone with New York, he’d turn to Roz and make the same joke about having fled a slave ship only to wind up on the Titanic.

New titles were being invented, released, and then axed with dizzying turnover. If Kirby seemed to be getting more of his books canned than anyone else, that may have been because he was creating more new ones than anyone else. One heartbreaker—because the vision it offered of the future was so downright fresh and bizarre—was OMAC, a hero whose name was an acronym for “One Man Army Corps.” It was another idea Jack had had at Marvel and withheld. Done there, OMAC would have been Captain America in an era yet to come.

There were other books that came and went with little notice. Jack drew three issues of a new “kid gang” he created—the Dingbats of Danger Street—but DC only printed one.

OMAC

no. 1

September 1974

Art: Jack Kirby and Mike Royer

DC Comics

FIRST ISSUE SPECIAL

no. 6

September 1975

Art: Jack Kirby and Mike Royer

DC Comics

KAMANDI, THE LAST BOY ON EARTH

no. 1

October 1972

Art: Jack Kirby and Mike Royer

DC Comics

SANDMAN

no. 1

Winter 1974

Art: Jack Kirby and Frank Giacoia

DC Comics

Kirby even reteamed with Joe Simon for one comic: Joe was also conjuring up features for DC and, like everyone else, seeing them shot down like skeet. Some were Simon-Kirby retreads like new Young Love stories and old Black Magic ones. Joe also tried a kid gang, and DC killed his after one appearance, too. Then he proposed an innovative twist on the good name of Sandman and someone mused, Hey, maybe if Simon and Kirby get back together, the old magic will reignite. It was worth a try, so Jack drew Joe’s Sandman script and maybe there was a tiny spark there. They put it out in 1974 as a one-shot, but it sold well enough to prompt a few more.

Simon was on the outs with the company by then, so the few more were written by another writer, Michael Fleisher, who was much in favor with DC editor Joe Orlando. Kirby didn’t like the scripts, but what really scared him was that Orlando and Infantino loved them. If Jack reupped his soon-to-expire contract, he’d be writing less and drawing more scripts like those. The ongoing comic didn’t sell to readers, but it sold Jack on the idea, once and for all, that he didn’t belong at that company. (Time-Warner management would soon look at the overall sales and decide that Carmine Infantino didn’t, either.)

Not that life was all bad. Jack’s favorite labor of the period was a tour of duty on an extant war strip called The Losers, an assemblage of characters from cancelled DC combat titles. Kirby didn’t like the jerry-rigged premise, and he especially hated the title, Losers being the last thing he would have called a band of Americans fighting in World War II. But it was an assignment and a chance to dip into his bottomless supply of combat experiences . . . so all in all, not a bad gig.

In 1975, when his contract was up, he returned to Marvel, viewing it as the better of two depressing choices. They welcomed him back and let him write/draw/edit his own comics, on his own. Some were all new, like The Eternals, a Kirby extrapolation on the Chariots of the Gods theory that aliens had visited Earth in prehistoric times. It was a speculation that had long interested Jack, even if he didn’t accept it as probable. In a playful mood, he’d argue, “Can you prove it couldn’t have happened that way?”

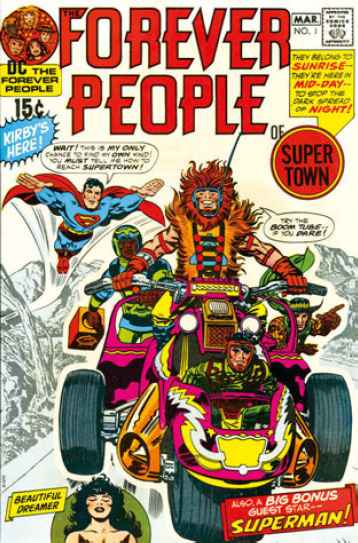

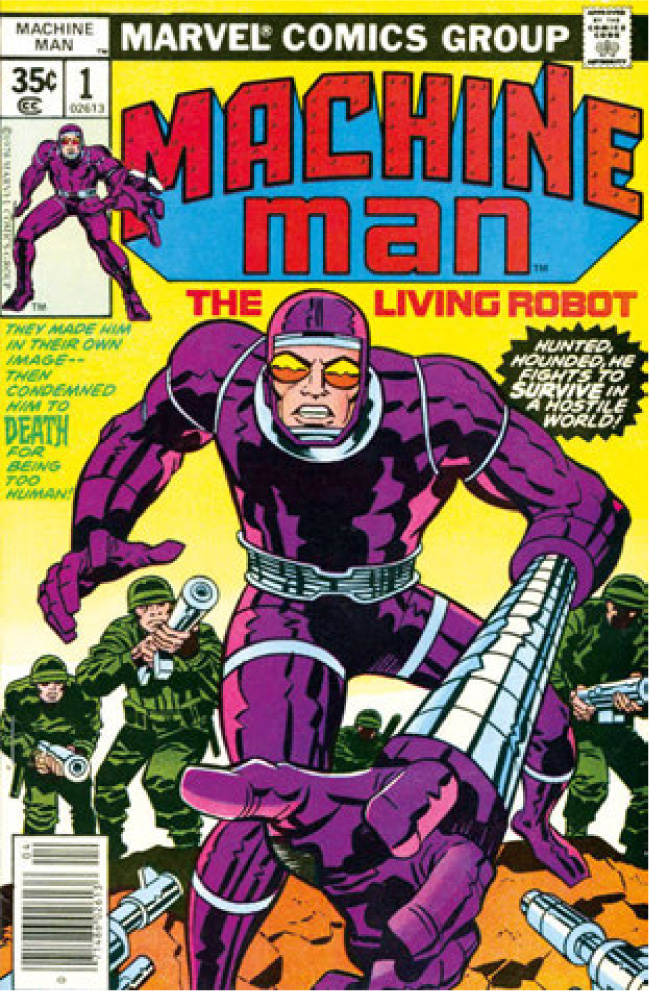

Some comics he worked on were adaptations. Jack was charged with the seemingly impossible task of converting Stanley Kubrick’s classic science-fiction movie 2001: A Space Odyssey into a seventy-one-page tabloid comic book version (1976). Somehow he managed, though there was little of his own vision in the storyline, and he described it as “an honor, but not a lot of fun.” What made it work was that the art—probably the best he did during this period—captured the visual imagery of the motion picture better than anyone had dared expect. It led to an ongoing anthology title—which, in turn, led to an original spin-off book, Machine Man, about an android fleeing a superannuated military industrial complex of the future.

And some comics were old friends revisited. Jack returned to Captain America in 1976, and did a new series of The Black Panther (1977), taking both off in new, Kirbyesque directions. Many readers (and some in the office) were bothered that those directions did not coincide with the tidy inter-continuity of the Marvel Universe. Others disliked Jack’s writing style or felt his art was getting sloppy. That eye was really starting to bother him by now, making drawing more painful and skewing his perspectives in odd slants. His inkers would do what they could to compensate, but it was becoming obvious to anyone who looked past the surface excitement: Something was wrong.

CAPTAIN AMERICA

no. 193

January 1976

Art: Jack Kirby and John Romita

Marvel Comics

THE ETERNALS

no. 1

July 1976

Art: Jack Kirby and Frank Giacoia

Marvel Comics

THE ETERNALS

no. 18

December 1977

Art: Jack Kirby and Mike Royer

Marvel Comics

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

no. 3

February 1977

Art: Jack Kirby and John Verpoorten

Marvel Comics

Something was wrong with the sales, too. Jack wasn’t connecting with the current Marvel readership, partly because he wasn’t connecting with the current Marvel line. Years after, his seventies work would be regarded more favorably and even reprinted, right along with almost everything else he did, time and again. Some would even say the sales figures weren’t as dire as the rumors of the time insisted.

But that was later. Just then, he’d stopped being Jack Kirby, the guy who created, or co-created, so many successful new comics. With the end of his contract in sight, he was Jack Kirby, the guy who did those wonky, unreadable books that didn’t sell so great. “Jack the Hack,” some called him, implying that he’d clearly stopped caring.

That hurt—hurt him a lot—because he was working harder than ever, with less and less to show for it except dwindling hope and eyesight. Even his boundless imagination couldn’t fathom how things might get any better, especially feeling as much hostility from the Marvel editorial staff as he felt. The one person there he thought respected him was the editor in chief, Archie Goodwin. Then Goodwin told him he’d be stepping down in the foreseeable future . . .

There had to be something else. But even Jack Kirby—the man who specialized in thinking of things no one else had ever thought of before—couldn’t figure just what it might be.

BLACK PANTHER

no. 1

January 1977

Art: Jack Kirby and John Verpoorten

Marvel Comics

MACHINE MAN

no. 1

April 1978

Art: Jack Kirby and Frank Giacoia

Marvel Comics

DESTROYER DUCK

Unfinished page

1982

Art: Jack Kirby