I NEVER MET JACK KIRBY, which makes me less qualified than a thousand other people to write this introduction. I saw Jack, the man, once, across a hotel lobby, talking to my publisher. I wanted to go over and be introduced, but I was late for a plane and, I thought, there would always be a next time.

There was no next time, and I did not get to meet Jack Kirby.

I had known his work, though, for about as long as I had been able to read, having seen it on imported American comics or on the two-color British reprints that I grew up on. With Stan Lee, Kirby created the original X-Men, the Fantastic Four (and all that we got from that, the Inhumans and the Silver Surfer and the rest), and the Mighty Thor (where my own obsession with myth probably began).

And then, when I was eleven or twelve, Kirby entered my consciousness as more than the other half of Smilin’ Stan and Jolly Jack. There were house ads in the DC Comics titles I was reading that told me that “Kirby Was Coming.” And that he was coming to . . . Jimmy Olsen. It seemed the least likely title Kirby could possibly turn up on. But turn up on Jimmy Olsen he did, and I was soon floundering delightedly in a whirl of unlikely concepts that were to prove a gateway into a whole new universe.

Kirby’s Fourth World turned my head inside out. It was a space opera of gargantuan scale played out mostly on Earth with comics that featured (among other things) a gang of cosmic hippies, a super escape artist, and an entire head-turning pantheon of powerful New Gods. Nineteen seventy-three was a good year to read comics.

And it’s the Iggy Pop and the Stooges title from 1973 that I think of when I think of Jack Kirby. The album was called Raw Power, and that was what Jack had, and had in a way that nobody had before or since. Power, pure and unadulterated, like sticking knitting needles into an electrical socket. Like the power that Jack conjured up with black dots and wavy lines that translated into energy or flame or cosmic crackle, often imitated (as with everything that Jack did), but never entirely successfully.

Jack Kirby created part of the language of comics and much of the language of super-hero comics. He took vaudeville and made it opera. He took a static medium and gave it motion. In a Kirby comic the people were in motion, everything was in motion. Jack Kirby made comics move, he made them buzz and crash and explode. And he created . . .

He would take ideas and notions and he would build on them. He would reinvent, reimagine, create. And more and more he built things from whole cloth that nobody had seen before. Characters and worlds and universes, giant alien machines and civilizations. Even when he was given someone else’s idea he would build it into something unbelievable and new, like a man who was asked to repair a vacuum cleaner, but instead built it into a functioning jet pack. (The readers loved this. Posterity loved this. At the time, I think, the publishers simply pined for their vacuum cleaners.)

Page after page, idea after idea. The most important thing was the work, and the work never stopped.

I loved the Fourth World work, just as I loved what followed it—Jack’s magical horror title, The Demon; his reimagining of Planet of the Apes (a film he hadn’t seen) with Kamandi, The Last Boy On Earth; and even loved, to my surprise, because I didn’t read war comics but I would follow Jack Kirby anywhere, a World War II comic called The Losers. I loved OMAC, “One Man Army Corps.” I even liked The Sandman—a Joe Simon-written children’s story that Jack drew the first issue of, and which would wind up having a perhaps disproportionate influence on the rest of my life.

Kirby’s imagination was as illimitable as it was inimitable. He drew people and machines and cities and worlds beyond imagining—beyond my imagining anyway. It was grand and huge and magnificent. But what drew me in, in retrospect, was always the storytelling, and in contrast to the hugeness of the imagery and the impossible worlds, it was the small, human moments that Kirby loved to depict. Moments of tenderness, mostly. Moments of people being good to one another, helping or reaching out to others. Every Kirby fan, it seems to me, has at least one story of his they remember not because it awed them, but because it touched them.

I did not meet Jack Kirby. Not in the flesh. And I wish I had walked across that room and shaken his hand and, most important, said thank you. But Kirby’s influence on me, just like Kirby’s influence on comics, was already set in stone, written across the stars in crackling bolts of black energy dots and raw power, and honestly that’s all that matters.

— NEIL GAIMAN

SEPTEMBER 2007

LONDON

P. S. In a perfect universe you would walk around a huge Kirby museum and stare at Kirby originals and also at the printed and colored versions of Kirby’s art, and Mark Evanier would stroll along beside you, telling you about what you were looking at, what it is, when and how Jack did it and why, because Mark is wise and funny and the best-informed guide you could have. He knows stuff. But this is not a perfect world and that museum does not exist, not yet, so you will have to settle for Mark Evanier on the pages of this book.

NEIL GAIMAN is a critically acclaimed and award-winning author of science fiction and fantasy short stories and novels, graphic novels, children’s books, and films. Among his many awards are the Newbery and Carnegie Medals, as well as the World Fantasy Award, four Hugo Awards, two Nebula Awards, four Bram Stoker Awards, six Locus Awards, the Harvey Award, and the Eisner Award. He is the author of The New York Times bestsellers Stardust, Coraline, Anansi Boys, The Graveyard Book, and Sandman. Originally from England, Gaiman now lives in the United States.

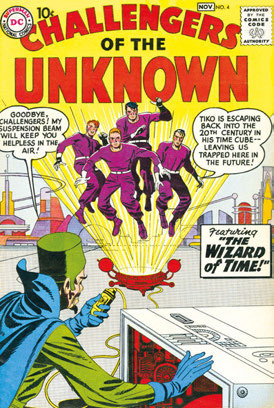

CHALLENGERS OF THE UNKNOWN

no. 4

October 1958

Art: Jack Kirby

DC Comics

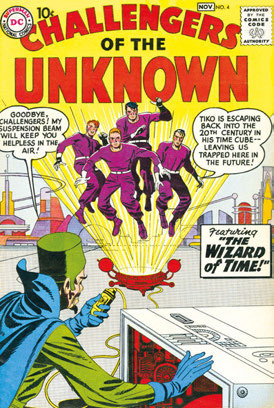

TALES OF SUSPENSE

no. 14

February 1961

Art: Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Marvel Comics

FANTASTIC FOUR

no. 29

August 1964

Art: Jack Kirby and Chic Stone

Marvel Comics

THE INCREDIBLE HULK

no. 2

July 1962

Art: Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko

Marvel Comics

THE X-MEN

no. 14

November 1965

Art: Jack Kirby and Wallace Wood

Marvel Comics

THE NEW GODS

no. 5

October 1971

Art: Jack Kirby and Mike Royer

DC Comics

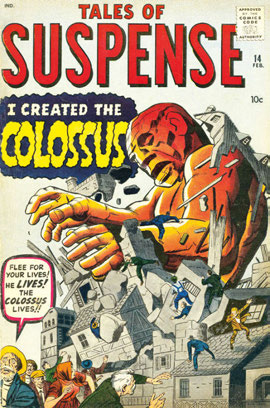

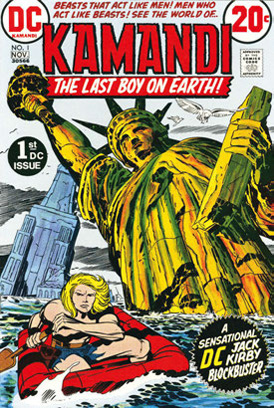

KAMANDI, THE LAST BOY ON EARTH

no. 1

October 1972

Art: Jack Kirby and Mike Royer

DC Comics

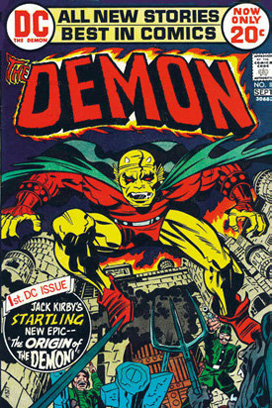

THE DEMON

no. 1

August 1972

Art: Jack Kirby and Mike Royer

DC Comics

DESTROYER DUCK

no. 1

1982

Art: Jack Kirby and Neal Adams

Eclipse Comics

Self-portrait from Marvelmania International

1969

Art: Jack Kirby and Mike Royer

Color: Tom Ziuko

This was Mike Royer’s first inking assignment over Kirby pencil art.