Chapter Twenty-Five

Lighting Effects in the Early Modern Private Playhouses

Lauren Shell

Throughout the history of theater, lighting techniques have grown from candles over a stage to computerized intelligent lighting. No matter how far technology progresses, one thing remains constant: it all began with fire. In our quest to understand original practices from the early modern theaters, we must come to the realization that lighting design is not a modern concept. Designing stage illumination began as far back as the Greeks and the Romans with their outdoor amphitheaters. They used torches during masques and festivals, thus beginning the age of thoughtful theatrical lighting. In Italy, centuries before England’s first indoor playhouse was ever built, great Italian architects such as Sebastiano Serlio and Nicola Sabbatini, as well as German architect Joseph Furttenbach, paved the way for modern lighting techniques. Their designs and recipes for everything from colored lighting to explosive lightning bolts opened doorways for the theaters in England that would have otherwise remained closed. Inigo Jones, the great traveler and architect, studied these men and their work. The knowledge he obtained by visiting Italy spread to England, its courts, and its playhouses. As the conduit for lighting innovations in England, Jones created masterful works of art both onstage and behind the scenes. Jones’s work, however, was not the only way in which the growth of lighting design came about.

By examining all of the aspects that helped contribute to the lighting effects in the early modern private playhouses, we can begin to make justifiable and reasonable assumptions about the progress of lighting techniques and their uses throughout the early modern theatrical world. This knowledge will require us to redefine our ideas of original practices as far as universal lighting is concerned. Instead of trying to recreate what is generally thought of as an even wash of light both onstage and throughout the house, we should begin to explore the nuances of early modern lighting effects. Theatrical lighting effects were carefully planned and executed. By studying their history and movement through Europe, we can begin to see lighting effects and their uses as important tools for the early modern English theaters.

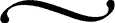

Some of the most influential people concerning lighting design came from Italy. Their work greatly contributed to the spread of lighting techniques throughout Europe. Serlio’s Architettura provides information that solidifies the knowledge of a conscious lighting design throughout the Italian theaters. For instance, at the end of book 2, Serlio listed the ingredients he used to create colored lighting. He explained that if “you make an emerald color, then put some saffron as you will have it pale or high colored” and that when making “a ruby color . . . if you can get no wine . . . take brazill beaten to powder and put into a kettle of water with alum, let it seethe, and skim it well; then drain it, and use it with water and vinegar.” Serlio also gave examples of different types of liquids that could be mixed together or used separately to make an even wider gamut of colors: “white wine alone will show like a topaz or a crisolite: the conduit or common water being strained, will be like a diamond.”1 These techniques were the beginnings of our modern-day gels. Once the glasses were full of each specific color, Serlio decorated the stage with them. He fastened them to set pieces while at the same time he secured candles behind each bottle so that every color could be seen (figures 25.1 and 25.2).

Figure 25.1.

Figure 25.2. Reproductions of Serlio’s colored lighting. Photos by Lauren Shell.

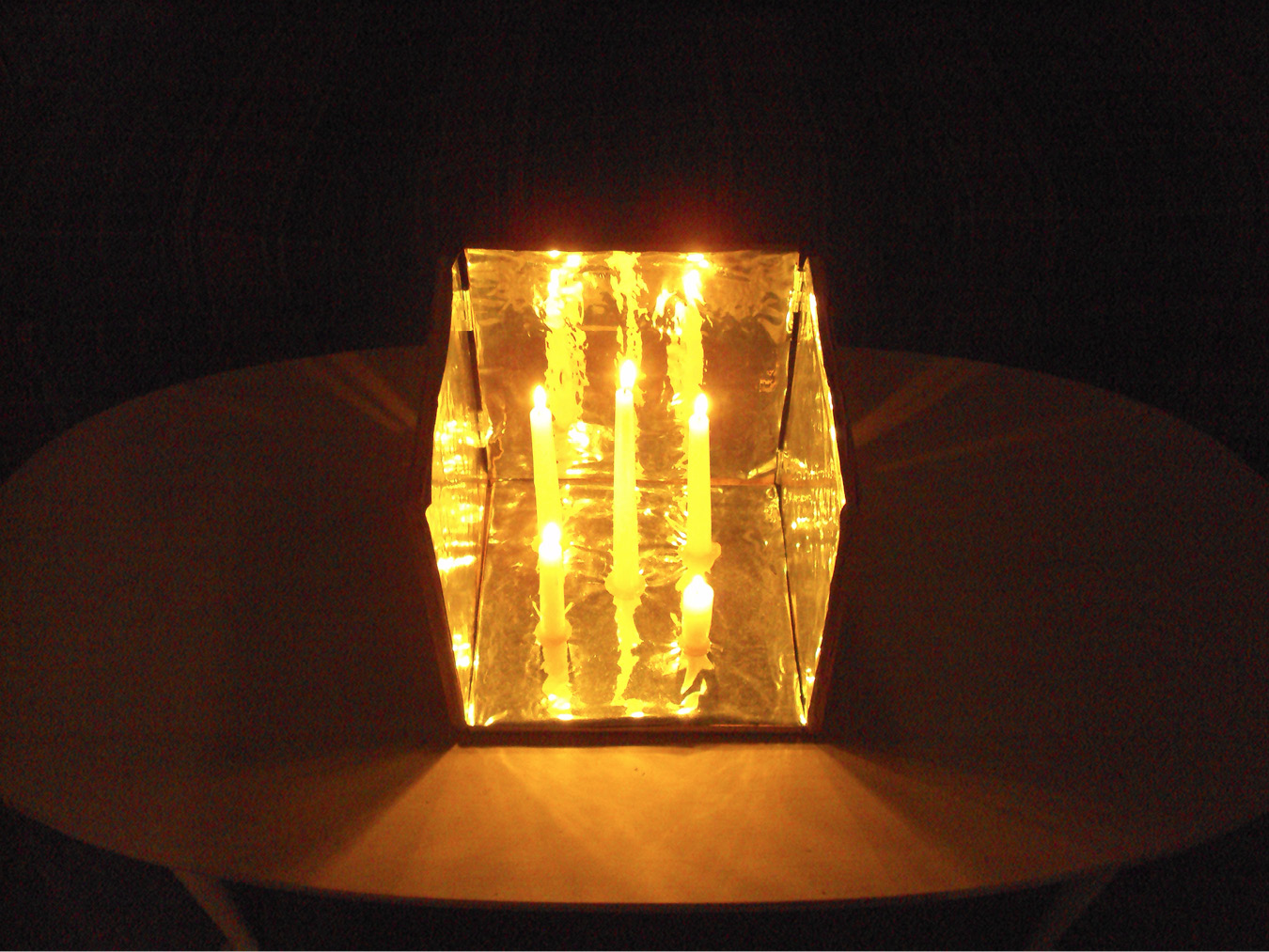

Likewise, Sabbatini’s Pratica di Fabricar Scene e Machine ne’Teatri (1638) described in detail lighting techniques used in Italian theaters during his time. Pratica is simply a manual with step-by-step instructions for anyone who wanted or needed to change an already existing hall into a workable theater space.2 One of the most interesting innovations regarding universal lighting can be found in chapter 12, which included a method for darkening the entire scene “within a moment” without having to actually put the candles out. The evidence and designs for this device prove their practicality for and use in the Italian theaters. This darkening method opens many doors for speculation about how often such a device was used or if it became a regular convention that Italian playgoers came to expect. Sabbatini advises that for as many candles as needed to be darkened, cylinders of tin at “least 1/2 a foot high [and] a little less in diameter” needed to be constructed.3 These cylinders were then attached to a cord, which was fixed to a pulley system. At the right time a workman lowered the cord, and all of the cylinders attached to it lowered onto the lamps to darken them. When the stage needed to be illuminated again, the workman simply pulled the cord up, and the stage was again in full light (figures 25.3 and 25.4).4

Figure 25.3.

Figure 25.4. Reproductions of Sabbatini’s dimmer device. Photos by Lauren Shell.

Germany was also at the forefront of creating theatrical lighting conventions. Furttenbach, a German architect from the early to mid-seventeenth century, wrote a book entitled The Noble Mirror of Art, in which he provided a ground plan for a theatrical space with specific instructions as to how the space should be built. The instructions he left shed some interesting light on the actual amount of daylight that audiences would sit in while watching plays. It is currently assumed that audiences were at the mercy of the daylight shining through the windows and large amounts of candles throughout the auditorium area. Furttenbach, however, wrote about the ideal placement of windows and made it abundantly clear that “it were better if no windows were put at the sides of the audience, so that the spectators, left in darkness like night, would turn their attention to the daylight on the stage.” This evidence directly challenges our views of universal lighting and suggests that perhaps there was some attempt to separate the audience from the actors. Furttenbach was aware of the fact that having no windows meant no airflow for the audience, so he added that there should be a window placed every tenth bench, but that the windows should be covered before the show started by either shutters or vines. By the placement of the greenery over the windows, audiences could enjoy the fresh breeze and cool air without being disturbed by a glare from the sun. Furttenbach worried about the contentment of the audience members in theaters and said that “every care should be taken for the welfare of the audience—that the spirit may be refreshed and not dampened.” He knew that many people in close proximity of each other would stifle the air and that the architect “would be held a simpleton” if he did not create some way for the air to circulate.5

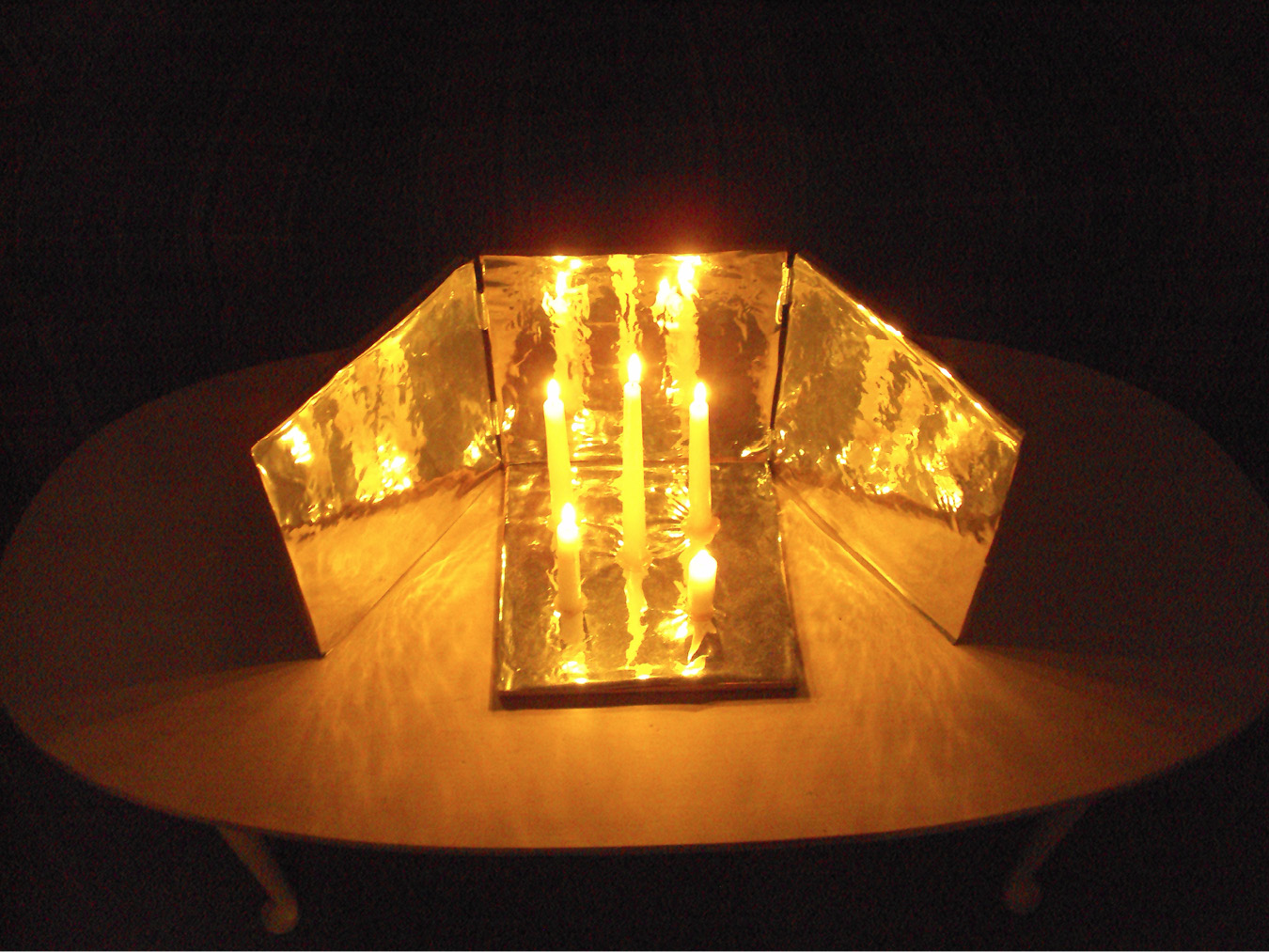

In another chapter entitled “Four Different Methods of Lighting,” Furttenbach provided four different ways to light a stage, complete with a diagram of each. These diagrams help give insight into the development of German lighting effects as well as the progress of lighting design across the continent. For the purpose of this research, I focused only on the fourth method described by Furttenbach. This method of lighting consisted of a candle sitting on a mica reflector while surrounded on three sides by other mica reflectors. The standing light box created such a brilliant display of light that it was commonly used when a scene called for a sudden burst of light (figures 25.5 and 25.6).6

Figure 25.5.

Figure 25.6. Reproductions of Furttenbach’s fourth method of lighting. Photos by Lauren Shell.

While these Continental designers documented theatrical lighting, Inigo Jones caught their vision and created performances beyond imagination. On Twelfth Night in 1605, Inigo Jones and Ben Jonson collaborated for the first time on a masque called The Queenes Masque of Blacknesse, to be played in Whitehall, in honor of Queen Anne. Jones took the knowledge he gained from his time in Italy and adapted it for the early modern English stage. Jonson incorporated into the script long, verbose descriptions of the stage effects, in which he informs us that “The Masquers were placed in a great concave shell, like mother of pearl, curiously made to move on those waters and rise with the billow; the top thereof was struck with a cheveron of lights, which, indented to the proportion of the shell, struck a glorious beam upon them, as they were seated one above another.”7

Then in 1609, Jones began work on another masque, called The Masque of Queenes Celebrated from the House of Fame, also written by Jonson. Gotch goes as far as to say that this masque represents the culmination of all the work Jones previously did, and at this point, it was the most spectacular design he had ever created.8 Jones designed a House of Fame for this masque that embodied many of the techniques previously mentioned about Serlio’s colored lighting. It contained friezes that were “fill’d with several-colour’d lights, like Emeralds, Rubies, Saphyres, Carbuncles, &c., the reflexe of which, with other lights placed in the Concave, upon the Masquers habits was full of glory.”9 Jonson described the House as “glorious” and “magnificent,” while the masquers sitting in it were “circled with all store of light.”10 In fact, Jones’s masques, at one point or another, used all three of the aforementioned lighting effects, in combination with many more.

Not only did Jones work in the courts’ halls, but he was active in the theater world as well. It is believed that he drew up ground plans for the Cockpit or Phoenix in Drury Lane. That theater is often referred as Jones’s theater. The hand that Inigo Jones had in the planning and execution of his designs for this playhouse only further solidifies the argument for the crossover between the world of masques and the world of plays. Jones was not the only man to travel in different circles. The playwrights of the time would have either seen the masques being performed in the court or have been informed about them through eyewitnesses. The elaborate sets and special lighting effects would not have gone unnoticed. The fact that Jones moved back and forth between the court and the private playhouses almost guarantees that ideas and suggestions were also passed back and forth. Playwrights began to incorporate stage directions that were more elaborate, and miniature masques were inserted into plays as either part of the action or as an interlude.

The evidence of lighting effects crossing over from the courts to the private playhouses is undeniable. The Blackfriars was, in fact, known for its masque-like performances. During the 1637–1638 season, the Blackfriars company put on a show called Aglaura by Sir John Suckling, which had previously been performed in court. The play was so elaborate and memorable that years later, during the Restoration, John Aubrey wrote notes on Suckling saying that “when his Aglaura was [acted] . . . he had some sceanes to it, which in those dayes were only used at masques.”11 Tiffany Stern writes in her essay “Taking Part: Actors and Audience on the Stage at Blackfriars” that “play masques often mirrored or were watered-down versions of known court favorites.” For example, the morris dance in The Two Noble Kinsmen came from Beaumont’s Masque of the Inner Temple, while the madmen’s morris from The Duchess of Malfi came from Thomas Champion’s The Lords’ Masque.12

Early modern English private playhouses turned what appears to be a weakness or flaw in design into the theatrical wonders of their time. If one examines the stage directions from the plays performed there and the dialogue of the characters themselves, well-grounded evidence for the lighting and lighting effects in the private playhouses arises. For instance, within early modern plays several types of darkness scenes occur, scenes that take place at night, which called for a variety of audience participation. W. J. Lawrence divides the night scenes into three classes, but for this study only class 1 and class 2 need to be examined. Class 1 is a scene in which both the text and a handheld property brought onstage hint at the lateness of the hour, while class 2 is a completely dark scene, whether real or imaginary, which remains without any light source.13 These darkness scenes centered around two important aspects of a play: the stage directions and the dialogue.

Stage directions and dialogue are two of the only remaining links we have to discovering the truth behind special lighting effects. Class 1 darkness scenes consist of a combination of dialogue and text. In act 5, scene 3 of Much Ado about Nothing, Claudio enters with the prince and “three or four with tapers” (1.3.0) to pay their respects to the dearly departed Hero. After singing a song at Hero’s tomb, Claudio says “Now, unto thy bones good night” (1.3.22), after which Don Pedro replies and says “Good morrow, masters, put your torches out” (1.3.24). This class 1 darkness scene uses torches to signify the darkness but is then backed up with the lines pertaining to nighttime and then the morning. Class 1 darkness scenes were common in both the private and public playhouses, especially when there was no way to darken the theater space. These scenes would present and define the darkness through actions and language rather than actual darkness.

Class 2 darkness scenes represent some of the most intriguing questions for illumination studies. As a way to cover all possibilities, Lawrence makes sure to add that the darkness might have been real or imaginary. This conjecture is readily backed up with textual evidence to support both types of dark scenes. Perhaps the most well-known darkness scene in an early modern play can be found in act 4, scene 1 of The Duchess of Malfi. The title page of the 1623 first edition clearly says that this play was “presented privatly, at the Black-Friers; and publiquely at the Globe.”14 Due to this information, we know that it could have been performed in the dark at the Blackfriars, but would also have been performed in daylight at the Globe. In act 4, scene 1 Bosola requests that the duchess have “neither torch nor taper / Shine in [her] chamber” in order that her brother, Ferdinand, keep his “solemn vow / Never to see [her] more” (4.1.23–26). Once the duchess orders her servants to “take hence the lights,” Ferdinand enters and immediately asks “Where are you?” (4.1.29). Once Ferdinand offers a hand in reconciliation, the stage direction reads, “gives her a dead man’s hand” (4.1.43). At this point, the duchess kisses the hand and remarks on how cold it is. She is then horrified to discover the dead man’s hand resting upon her lips.

John Russell Brown argues that this scene can only be effectively done in a darkened theater so that the audience experiences the same shock as the duchess when the severed hand is revealed. The title page of this play, however, tells us that this would have been impossible at the Globe. According to Brown, with no way to darken the theater, the gruesome reveal would not have been as effective for the audience.15 I argue that there was no way for the Blackfriars to become completely dark for this scene. The idea of removing the entire chandelier light and all the sconces along the walls is impractical and nearly impossible to do quickly enough. It is here that I propose the use of Sabbatini’s dimming device as a solution. If the dimming devices were lowered over the chandeliers at the appropriate time, it would create a low, dimly lit acting space, but would still allow for the actors to move around safely while providing the audience with just enough light to witness the horrifying scene. This scene is, in fact, more gruesome when the audience is aware of what the duchess experiences, but can do nothing to stop her. One should not assume that there was either full light or no light involved. Taking the dimming devices that were currently being used in court plays and masques and assigning them to the private playhouses remains a distinct possibility. In fact, doing so would help explain the difference between stage directions that read “as if groping in the dark” (D4.5), as in Thomas Heywood’s The Iron Age, Part II and “a darkness comes over the place” (1.1.312) as in Ben Jonson’s Catiline. They should not be read as the same type of stage direction. If it were not possible to create “a darkness” onstage, Jonson could have easily written “as if a darkness comes over the place.” These slight textual variations imply the difference between perceived darkness and actual darkness.

These “pictures with Light and Motion” gave private playhouses the ability to bring the sophistication of the court to another type of audience.16 When Prospero begins his masque performance in The Tempest, his last words before it starts, “No tongue, all eyes! Be Silent,” refer not to the aural, but to the visual.17 These stunning performances included lighting effects that had never been presented in England’s theaters before. Our ideas of universal lighting, with its static chandelier levels and ability to see everyone clearly around you, simply are not founded in early modern texts. Lighting effects became an important aspect of the theater through the popularity of the court masques and the work of Inigo Jones. What Milton came to call the “Commonwealth triumphs” was Jones’s ability to change the world of theater forever. His foray into the world of theatrical lighting, a foray that resulted from his knowledge of Continental lighting innovations, gave us “the power to create a hero by controlling the way we look at a man.”18

Notes

1. Sabastian Serlio, The Book of Architecture (New York: Benjamin Bloom, Inc., 1970), 26.

2. Barnard Hewitt, ed., The Renaissance Stage: Documents of Serlio, Sabbatini and Furttenbach (Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Press, 1958), 37.

3. Hewitt, 111.

4. Hewitt, 112.

5. Hewitt, 206.

6. Hewitt, 237.

7. Inigo Jones, Designs by Inigo Jones For Masques & Plays at Court (New York: Russell & Russell, 1966), 12.

8. Jones, 47.

9. Allardyce Nicoll, Stuart Masques and the Renaissance Stage (New York: Benjamin Bloom, Inc., 1938), 135.

10. Stephen Orgel, The Jonsonian Masque (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965), 138.

11. Gerald Eades Bentley, The Jacobean and Caroline Stage, vol. 6 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), 38.

12. Tiffany Stern, “Taking Part: Actors and Audience on the Stage at Blackfriars,” in Inside Shakespeare: Essays on the Blackfriars Stage, ed. Paul Menzer (Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press, 2006) 48–49.

13. William Lawrence, The Elizabethan Playhouse and Other Studies, vol. 2 (New York: Russell & Russell, 1963), 7.

14. R. B. Graves, Lighting the Shakespearean Stage, 1567–1642 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999), 220.

15. Graves, 222.

16. Stephen Orgel, “The Poetics of Spectacle,” New Literary History (Grafton Library, Staunton, October 3, 2007), 367–89.

17. Orgel, 367–89.

18. Orgel, 367–89.