TEN

THE SALON OF THE CENTURY

Artist, thou art priest: Art is the great mystery; and if

your attempt turns out to be a masterwork, a divine ray

descends as on an altar. Oh real presence of the divinity

resplendent under these supreme names: Vinci, Raphael,

Michelangelo, Beethoven, and Wagner. Artist, thou art

king; art is the real kingdom. When the hand draws a

perfect line, the cherubim themselves descend and take

pleasure there in themselves as in a mirror. . . . Drawing of the spirit, outline of the soul, form of understanding, you embody our dreams, . . . Artist, thou art magus: art is the great miracle and proves our immortality.

Who still doubts? Giotto has touched the stigmata, the Virgin appeared to Fra Angelico; and Rembrandt has proved the resurrection of Lazarus. . . .

Miserable moderns, your course to nothingness is fatal; fall under the weights of your indignity: your blasphemies will never efface the faith of works, O sterile ones!

You could some day close the Church, but the museum? Le Louvre will officiate, if Notre Dame is profaned.

Brothers of all the arts, I here ring the bell to fight; form a holy militia for the salute of idealism. We are few against all, but the angels are ours. Our chiefs are the old masters in the heights of paradise, who will guide us towards Montsalvat. . . .

Oh you, who hesitate, my brother, do not misinterpret or confound the fire of Faith with the cry of the fanatic.

This Church so dear, the sole august thing in this world, banished the Rose and believed its perfume dangerous.

JOSÉPHIN PÉLADAN, PREFACE TO GESTE ESTHÉTIQUE, CATALOGUE DU SALON DE LA ROSE+CROIX, 7–11

Other than Péladan’s magical will, the person most responsible for getting Péladan’s dream successfully into the Gallery Durand-Ruel in 1892 was Count Antoine de La Rochefoucauld. But here lay obscured another fissure in Péladan’s ideal edifice, for while La Rochefoucauld, an artist himself, was enthusiastic for Péladan’s primary ideals, he had his own special tastes, tastes he wished to see promoted by the Rose+Croix+Catholique.

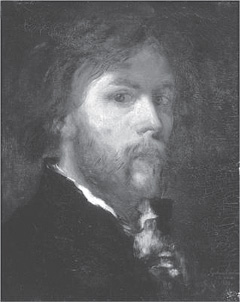

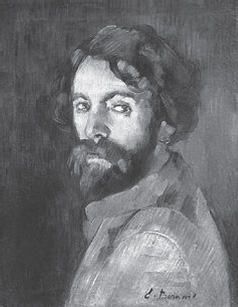

La Rochefoucauld was in sympathy with the Pont-Aven school of independent artists. Among those who gathered to paint in the spiritually congenial southwest coast of Brittany were Maurice Denis (1870–1943), Paul Ranson (1864–1909), Charles Filiger (1863–1928), and Paul Sérusier (1864–1927). Gauguin sojourned with them in 1888, leaving as winter approached to stay, fatefully, with van Gogh in Arles, before returning to Paris to share his ideas with Symbolists Aurier, Morice, Redon, Carrière, Moréas, and Mirbeau in the Café Voltaire in the Odéon district, attending admirer Stéphane Mallarmé’s Tuesday gatherings, while working toward his own Symbolist universe.

When not in Brittany, the three ex-students of the Académie Julian, Denis, Ranson, and Sérusier, would meet at Ranson’s studio on the boulevard du Montparnasse on Saturdays. Out of their discussions came a kind of manifesto, written by Maurice Denis and submitted to the review Art et Critique in 1890. Denis wrote of his dream of a brotherhood (the prophets or Nabis) whose aim was not to copy nature but to visualize their dreams through nature in order to recover spiritual vision. Nature served only to stimulate awareness of the symbol, for the spirit surpasses matter, and it is that—what Martinists would call “The Thing” or La Chose—that alone is worthy of brush and canvas. Strangely, John Lennon would come to an analogous conclusion in early 1969, when, in discussions with the other Beatles as to their future, he gave out that “God is the gimmick,” meaning that the essence of what he believed the Beatles should work for was cosmic consciousness, and while the music had obvious commercial value, that was not what it was essentially about; Beatles was a means to an end, a “medium of communication.”

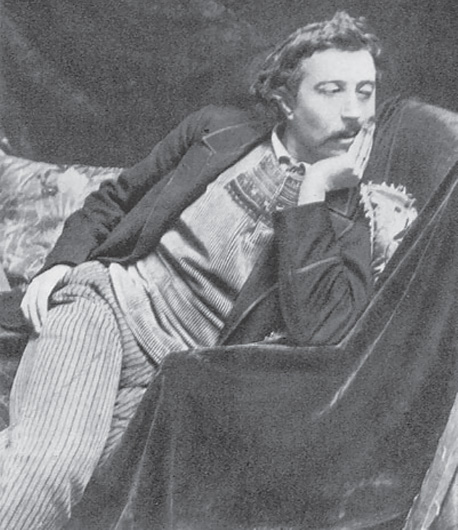

Fig. 10.1. Paul Gauguin in 1891

Fig. 10.2. Paul Sérusier (1864–1927)

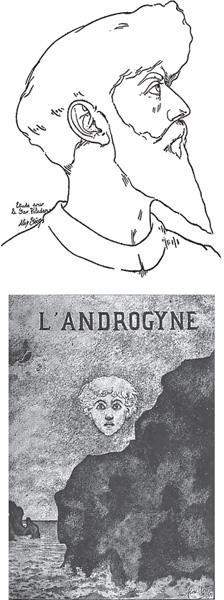

Fig. 10.3. Maurice Denis, drawing by Odilon Redon

Jean Cassou has expressed the Symbolists’ challenge to prevailing representational forms thus: “By reacting against the positivist spirit of its time, Symbolism found the way to discover the right language for man to recover his faith in the imaginary and the unreal.”1 While this comment might be applied to the decadently grandiose visions of Gustave Moreau, that last word unreal hardly applies to the austerity of the Pont-Aven school whose associates were seeking mystical, or “higher” reality in and through paint. It is not surprising that it would be this initially obscure wing of the Symbolist bird that would create the flight path for the revolution of abstraction.

Péladan himself assisted the process toward artistic revolution, for he believed the artist was bound to look through nature in search of the ideal idea that corresponded to the symbolic language of the soul and then to give that experience ideal form, or, to use Coleridge’s words, “to disembody the soul of fact.” This idea of abstraction—for you “abstract” the idea from the object—was central to Péladan’s thinking but curiously latent in his actual appreciation of different pictures. This was because his idea of abstraction was based precisely on Plato’s distinction of time and eternity—time being eternity’s “moving image”—distinctions best evinced in the works of da Vinci, in Péladan’s view. When the Symbolist reaches the essence of the task, he should be able, like a magician or alchemist, to abstract the Idea that is eternity from its image, time, or the products of time. In the hands of a great artist, for example, a ruin—an image that might otherwise suggest decay—may invoke eternity, the ideal world beyond time and space. The tension between the decay and loss, and the idea of eternity, creates the drama of the artistic event: the invisible point of the painting.

Spiritual forms were still for Péladan essentially anthropomorphic, corresponding to the visual creation, though idealized: “God saw that it [the creation] was good.” Man is made “in the image of God.” The example above demonstrates Péladan’s difficulty in embracing complete abstraction from the visual plane. If creation is somehow redeemed through vision, one wants to see the created matter transformed, idealized—not denuded or “minimalized.”

Péladan’s idea of the ideal was highly influenced by the Italian Renaissance and Hermetic revival of the Quattrocento that stressed human form as the ideal form of divine beauty, and androgynous form as the spiritual ideal—hence Péladan’s great love for da Vinci’s John the Baptist. One was unlikely to be tempted to fall in love, worship, or risk all, for a triangle! Magnum miraculum homo est! Geometry for Péladan, as for most occultists, referred to the essential construction or plan of a work, divine or symbolic proportions implicit to a great work. To replace a great painting merely with its geometrical lineaments would have been the aesthetic equivalent of stripping the Venus de Milo to the bare bones: What was the point? The difference between a skeleton and a truly ideal form was life: “the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.”

However, it only remained for new artists to decide there was a point, and that ideas could be expressed in abstract forms that had life of their own, for the bonds that bound paint to identifiable objects to dissolve. The first step only required a transition of interest to Plato’s inherited tools of creation, the five primal geometrical solids. Once sacred geometry, such as the “golden section,” and symbolic numerology were combined, the path opened to the revolution in form and color, mentalized and spiritualized, we know as “Abstract Art.” We may therefore deduce that abstract art, while obviously “modern” on the stylistic, visual plane, was derived through an esoteric perception of Pythagoras, Euclid, medieval religious architecture, and occult traditions. Pont-Aven habitués Sérusier, Denis, Ranson, and, to some extent, Charles Filiger (regarded by Breton as a proto-surrealist) believed forms derived from these sources possessed their own ideal beauty, holding the secret keys to ideal form.

The revolution of abstraction must have seemed very distant at the time from what was exhibited under the auspices of the Salons de la Rose+Croix from 1892 to 1897, but in fact, it was already there, just under the surface. The sad thing perhaps is that while Péladan could grasp the revolutionary idea intellectually, he could only envision it in forms with which he was largely already familiar. This would mean that as the 1890s movements surged toward the colder lights of the twentieth century, Péladan’s objects of devotion would come to look rather old fashioned, and he, unjustly, with them. It would be abstract, spiritual pioneer Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) who would recognize and state the seminal importance of Péladan’s critical genius and pass on the torch of spiritual idealism in painted form. In his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky wrote: “The artist is not only a king, as Péladan says, because he has great power, but also because he has great duties.”2

Exercising those great duties would be an enormous trial for Péladan through the 1891–92 period. June 1891 saw Péladan compelled to take Léon Bloy and Léon Deschamps to court over a dispute stirred up in the pages of Léon Deschamps’s review La Plume the previous year. It centered on the fact that Bloy, close friend of Barbey d’Aurevilly—who had died in 1889—accused Péladan not only of having significantly darkened the last days of Barbey’s life, but also of having dishonorably exploited his contact with Bloy and the Barbey circle.

What in fact had happened in 1889 was that Péladan had informed an old flame of Barbey’s that the old man was dying, whereupon the woman arrived at Barbey’s house demanding, in very poor taste, money owed to her. When it transpired Péladan’s indiscretion had precipitated the unexpected scene, Bloy refused Péladan access to pray at his friend’s bedside, informing Péladan that Barbey, having tired of Péladan’s antics, regretted giving his first novel the boost of an endorsement.

The hearings, covered by La Plume, commenced on 15 June. Péladan insisted Bloy had falsified circumstances around Barbey’s death. In October the judgment found against Péladan and Bloy crowed his satisfaction in November’s La Plume. By that time, Péladan had already burned his boats with old friends at L’Initiation, who might otherwise have supported him through the interminable trough of ridicule that followed the judgment, though L’Initiation did print one letter in the otherwise critical July 1891 issue from a country subscriber who lamented the dispute between Péladan and Papus’s review, admiring all parties and calling for a spirit of ideal love and charity among men who were so important and who had spiritual responsibilities to those attracted to their cause. The editorial comment was that publication of the reader’s letter proved the review’s impartiality! To be fair, L’Initiation had certainly given Péladan a hearing, but had remained unmoved by what it heard. We shall see why shortly.

Péladan delivered a final word to L’Initiation on 17 February 1891, published in full in the April 1891 issue: the first article in a sequence followed by de Guaita on modern sorcery (again aimed at Boullan, though not naming him), and an article by gnostic bishop of Montségur, Jules Doinel, which sequence gives one a flavor of the time.

The “Avant-Propos” is headed by Péladan “MANDEMENT [Pastoral Letter] from the Sar Péladan, master of the catholic Rose-Croix, to Papus, president of the Esoteric Group and Director of L’Initiation.” Péladan goes right to the point of what separated him essentially from his old colleagues. It is the overexpansion, as Péladan sees it, of Papus’s eclectic doctrine—not a personal dispute with de Guaita as has usually been thought. Péladan disapproved of Papus’s policy, and a defensive Papus responded with an attack, as we saw in L’Initiation’s August 1891 “Supplement” in chapter 9. Papus could not stomach what Péladan here declares:

Salut, Light and Victory in Jesus Christ only God, and in Peter sole king.

Très cher Adelphe, [Note the French version of the Greek for “Brother” does not have the idiosyncratic initial E of the keyword Edelphe used by the Vicomte de Lapasse for genuine Rosicrucian physicians, as directed by “prince Balbani.” One wonders whether Péladan’s use of A was because he was unaware of the specialized, Paracelsian connotation of de Lapasse’s Edelphe taking it merely as an archaic spelling of Adelphe.]

A year ago, I wanted to leave your eclectic works; at your request, I accepted to figure, at the head of L’Initiation, with the quality of Roman Catholic Legate.

Today, the divergence of our paths has become such that my intransigence generates your expansion whilst my orthodoxy would suffer from your compromises.

This Catholic rigor that I manifested three times in le Figaro does not permit me to stay any longer as consort to a group where Cakya-Mouni [Buddha] usurps our Savior Jesus Christ.

That which for you comes under the rubric of comparative religion, I rather call sacrilege.

Regarding doctrines, the expansive mode divides us again: you would open the doors of the temple that I would like to close.

The implacable hierarchy that I recognize, you sacrifice to a proselytizing movement that I admire, but which I cannot associate myself with.

I therefore quit today and forever the work accomplished together.

Henceforth, I give my entire self to my Rose-Croix catholique.

Among yourselves, you often forget that I am the dean of works of this renewed magic wherein you occupy such a great place.

Among my own, one never forgets that you are one of my highest peers.

From this moment, the Church possesses the occult as I bring it to her, in my person, one of the six gnostic lights of the hour.

I go, with my brothers [adelphes] to wait for you before the Eucharistic altar, in the palace of ardent fire; and I hope one day to welcome you there with inexpressible laetare [rejoicing].

That this same light that we seek, you by numbers and diffusion, me by l’aristie and occultation, shining equally on our workman’s hands.

Materialism has found in you an invincible adversary, and, whatever the mutual and disparate necessities of our realizations, I salute your glory with my catholic enthusiasm because your initiates will become our faithful, as our faithful are your initiates.

Differing missions, one dedicated to disseminating truth, the other to the aestheticization of the truth. And verbum caro factum est [“the word was made flesh”]; and that the Absolute realizes itself, by you or by me, or by others non nobis sed mominis tui gloriae solae, [“not for us, but only to the glory of thy name”] said the Temple;

Ad Rosam per Crucem, ad Crucem per Rosam in êa in eis, gemmatus resurgam: [“Achieving the Rose through the Cross, achieving the Cross through the Rose in her in them, thus adorned I will be resurrected”] sings the catholic Rose-Croix in the name of that I salute you from heart and from spirit.

SAR PÉLADAN. This February 17 1891.3

As it turned out, Péladan only just got into the review before the Vatican took it out of his hands and placed it on the Index. The Catholic hierarchy got very close to putting Péladan’s own works there too. A provincial Catholic congress held at Malines in Belgium accused Péladan of dishonoring the faith, along with Baudelaire, Barbey d’Aurevilly, and Paul Verlaine. Doubtless flattered by the company, Péladan’s response was to excommunicate (!) the congress’s constituents in his “Ardent Execration of the Malines Catholic Congress,” published by Dentu in Péladan’s Règle of the Rose+Croix Salon in 1891, cosigned by “Le Grand Prieur [Grand Prior], A. De la Rochefoucauld.”

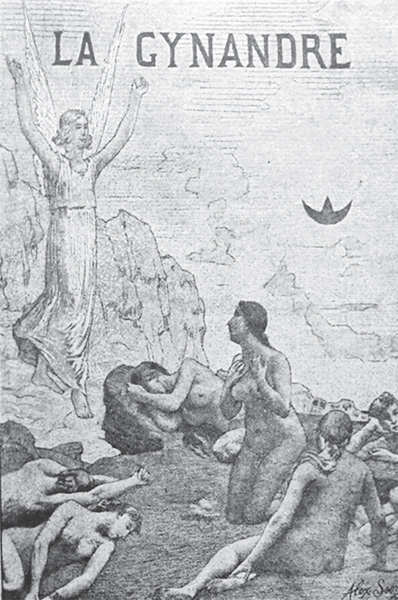

Péladan readers were greeted in May 1891’s Salon review not only with lengthy, rather over-the-top praise for the Sâr’s skillful portrait artist, Marcellin Desboutin—to whom Péladan’s new Sapphic novel Gynandre or the “Woman-Man” was dedicated—but a preview of some of the artists who would feature regularly in the Salons de la Rose-Croix.

Close friend of Seurat and Aman-Jean and trained in Lehmann’s studio, Alphonse Osbert’s style fitted perfectly the “mauve” decade’s crepuscular vision of intermediate life states. Influenced by the classical compositions of Puvis de Chavannes, Osbert employed his own pointillist technique that placed his subjects somewhere between life and death, time and eternity, making the viewer question his own perspective on both states.

Fig. 10.4. Frontispiece by Alexandre Séon for Péladan’s novel La Gynandre (The Woman-Man), from the catalog to the first Rose-Croix Salon 1892

Fig. 10.5. Hymne à la Mer by Alphonse Osbert, from the 1892 Rose-Croix Salon catalog

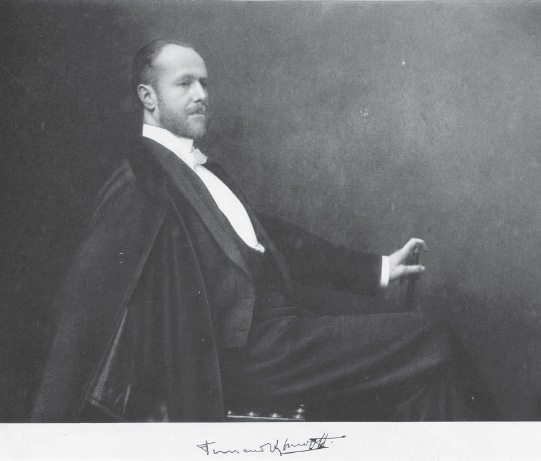

Fig. 10.6. Fernand Khnopff (1858–1921), self-portrait

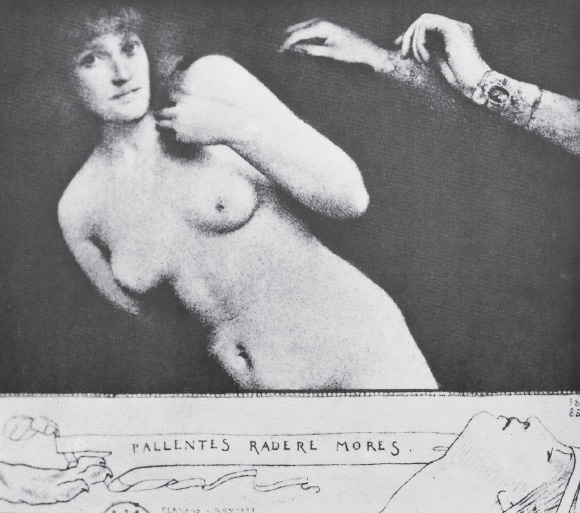

Fernand Khnopff, described by Péladan in Le Salon (Dixième Année, p. 23) as “so intense and subtle” had provided the almost kinky St. Sebastian–like frontispiece to Péladan’s Istar (1888). Khnopff, his name resonant of an Egyptian curse, will provide a style practically emblematic of the Salons collectively and of the era, the very definition in form of the phrase “the late antique”: mysterious, arcane, intellectual, haunted, and remote, a world where classical Roman and Greek certainties of logic melt in the monstrous seepage of conquered, chthonic spiritualities in the form of Middle Eastern chimeras, some erotic, others inscrutable. Burn your togas! The Age of Reason has had its day!

Péladan was likewise drawn to Alexandre Séon’s ability to paint the nightmares of genius. He had executed the cover for L’Androgyne, described in the Salon of 1891 (p. 40) as a work set above “the strange rocks of Bréhat, licked at by the waves, there rolls in the sky in place of the moon, the head of the androgyne Samas, stupefied by the sexual enigma.”

Séon’s unforgettably weird and disturbing Le Désespoir de la Chimère (The Despair of the Chimera—see color plate 18) shows us a kind of demented sphinx, most unhappy at her polymorphous incongruity as she screams like a strangled cock through lips stained with rouge on the edge of a coastal cave, the waves of time and space eroding its sense of existence. A midday nightmare at the seaside, it would appear as a shocking “Rosicrucian” vision at the third Salon de la Rose+Croix.

Péladan shared with all ancient civilizations the fascination for combined beings, firstly of men and women, boys and girls, but also of humans and animals, the most obvious examples being Pan and of course the Sphinx. Such combinations had great symbolic value, lost to the anthropocentricity of the modern world where different “classes” of being are kept apart. Being more concerned with soul than body, occult systems looked for the correspondences between them, while alchemists saw magic in combinations, seeking volatility.

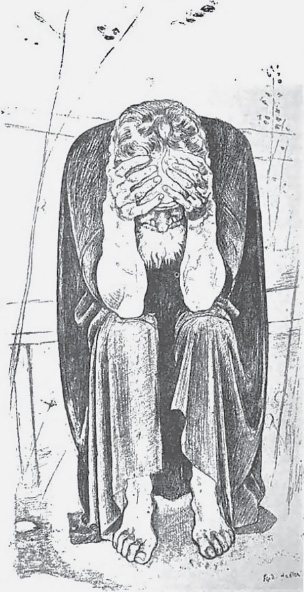

Péladan expressed admiration for the Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler who caused a sensation at the Salon with a painting reminiscent of Fuseli’s famous Nightmare. De La Rochefoucauld went to Switzerland in 1892 to persuade Hodler to exhibit for the Rose-Croix. The artist sent his Les Âmes Deçues (Disappointed Souls, see figure 10.7 below). Péladan would have noticed a resonance with Breughel’s blind leading the blind, for its five seated men with heads in hands all suggest a posture of penitence, though to this author the highly stylized image is more prescient of the condemned “Waiting for Godot,” for a genuine penitent should never be disappointed, nor would resort to a bench like a waiting room for hell.

Péladan’s Rose+Croix Ésthétique, drawn up on May 1891’s Feast of the Ascension and appended to the 1891 Salon critical publication, spelled out the aims of the Salons de la Rose+Croix. Addressing his “Magnifiques” in the Order, Péladan creates the Règle or “Rule” of the Salons to come. The use of the Rule comes straight from medieval monastic or chivalric orders where each was governed by a Rule. Theologian and founder of the Cistercian Order, Bernard of Clairvaux drew up the Templars’ Rule, for example. In conformity with Péladan’s ideal artist as priest, magus, and king, the Magnifique must live a dedicated life by adhering to a Rule. The new group is given its aims, predicated on the infallibility of the Sâr with the benefit of intercession with God of the effectively canonized Balzac (author of the androgyny-inspired novel Séraphîta, 1834), composer Wagner, and painter Delacroix, whose angels in St. Sulpice provided daily devotional inspiration:

Fig. 10.7. Les Âmes Deçues by Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918), from the first Rose-Croix Salon catalog, 1892

To insufflate theocratic essence into contemporary art, especially aesthetic culture, such is our new path.

To ruin the notion attached to facile execution; to extinguish methodological dilettantism, to subordinate the arts to Art, that is to say, to return to the tradition which regards the ideal as the single aim of the architectonic, the pictorial or plastic effort. (Salon, p. 55–56)

For Péladan, this amounted to “holy war” against philistines and materialists, and that is why his Order takes the name of the Temple, as well as the Graal. When in the early twelfth century St. Bernard of Clairvaux called together his “poor knights” to the Templar Rule, he thought of them as “Maccabees,” that is, holy warriors fighting for Zion against the heathen. Judas Maccabaeus led the second-century BCE revolt against Greek domination of the Holy Land. His name meant “the hammer.” Desiring to give the art world’s academicism and limp Impressionism a thorough hammering, Péladan summoned to order his “Maccabees of Beauty.” In bringing forth this level of mythic power, Péladan began to initiate his remarkable attempt to exotericize the occult and create from art, by and through art, the locus of a new, or revived, spiritual religion that could change the world without from within. Oscar Wilde, residing in Paris in late 1891 while writing the risqué symbolistic classic, Salome, must have been listening. James Webb wrote, with respect to Wilde: “The idea of the [Wildean] aesthetic movement was essentially a corruption of the doctrine of the French Symbolists” (The Occult Underground, p. 166). Salome’s French translation was the work of Symbolist intellectual and Gil Blas journalist, Marcel Schwob (1867–1905), who would perform the same service for Aleister Crowley’s Rodin in Rhyme in 1903. Crowley often took his cue from someone else.

When Les Petites Affiches carried the legal announcement of the Association de l’Ordre du Temple de la Rose-Croix on 23 August 1891, there was great public interest, satisfied by Péladan on 2 September with a popular version of the aims of the Order in Le Figaro called Le Manifeste de la Rose+Croix. A fascinating article, its second paragraph expresses the effort precisely in terms of, and as an illustration of, the thought of Fabre d’Olivet, who spoke of the sacred, transformative union of Will with Providence. Clearly Péladan saw himself as one of the “hommes providentiels” that Fabre d’Olivet believed to be incredibly rare, and who saved the world from oblivion:

Such a fuss [journalistic interest in the Order] bears witness that our Will, blessed by Providence, will polarize Necessity with Destiny.

The Salon de la Rose+Croix will be the first realization of an intellectual order that originates, by theocratic principle, with Hugh of the Pagans [cofounder of the Knights Templar]; with Rosenkreutz [legendary founder of the Rose-Cross brotherhood] by the idea of individualistic perfection.

The infidel today, he who profanes the Holy Sepulcher, is not the Turk, but the sceptic; and the militant monk [Templars were both monks and knight-warriors] with his motto “ut leo feriatur” [Templar motto attributed to St. Bernard of Clairvaux: “Let the lion be beaten down,” the lion being the animal passions] can no longer find a place for his effort. . . . The Salon de la Rose-Croix will be a temple dedicated to Art-God, with masterpieces for dogma and for saints, geniuses.4

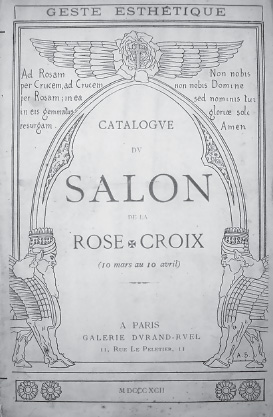

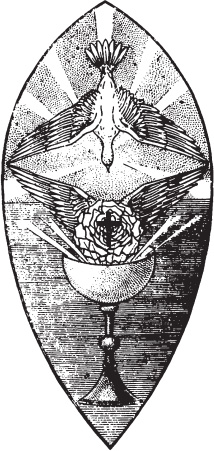

Fig. 10.8. Title page: catalog, first Rose-Croix Salon 1892

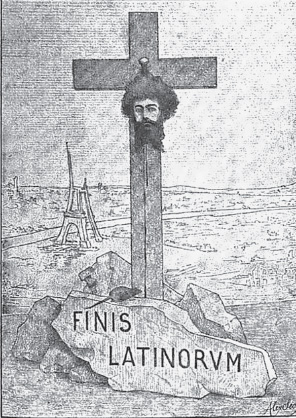

To get an instant sense of what Péladan was driving at, we need only look at the catalog for the first Rose+Croix Salon that came to pass in March and April the following year, that is, in 1892. The catalog’s pages consist mostly of drawings exhibited. In Alexandre Séon’s frontispiece for a new edition of Le Vice Suprême5 reproduced on page 64 of that document, we see the startling image of a Paris blown apart, devastated and flattened on a terrific scale worse than the Germans’ World War I bombardment of Liège; indeed, the scene seems chillingly prescient of Hiroshima’s annihilation. Only two identifiable objects are standing. One is what’s left of the Eiffel Tower (constructed 1887–89), either because it is depicted as partially obliterated by war, or simply not finished; the other is a standing cross on a hill occupying the foreground. On the cross, nailed up by abundant black hair is the severed head of Joséphin Péladan, like the prophet-Baptist. His eyes gaze into ours. He sees us, and we see the void. What void?

Below the severed head is an inscription: finis latinorum. This is the end of the Latin world, Latin culture, Latin idealism, Latin beauty, Latin faith, even Latin decadence in the form of the decapitated Sâr. If the barbaric enemy, by implication the Germans, has not completely wiped out the massive iron Eiffel Tower, it is because Péladan sees its iron hubris as in a sense “one of their own.” The viewer will have been aware that the place where this offensive Tower of Babel was erected for the World’s Exhibition of 1889—an erection opposed by hosts of writers and artists—was the Champ-de-Mars: the field of Mars, god of war, and the Champ-de-Mars was where the official Beaux Art Salons were held. Péladan sees what all this means. Fight for the spiritual culture of idealism—the Holy Graal—or look forward to the wasteland whose iron sign, devoid of symbolic value, is already towering over an apostate Paris, forcing us to see its significance!

Fig. 10.9. Alexandre Séon’s new frontispiece to Le Vice Suprême, from the catalog to the first Rose-Croix Salon 1892

That is what all Péladan’s posturing is fundamentally about. One could write pages on Péladan’s sometimes curious laws that were printed to govern conduct both within the Order and at the Order’s manifestation in the Salons, but while these laws had meaning, they were not, I think, to be taken entirely literally, as so many have, concluding that Péladan was a dotty eccentric. The rules were fundamentally an aesthetic abstraction from the rules of the militant monks of past times, whose ardent fervor for Christ, the living Word, had been forgotten by the skeptic, the materialist, the relativist, and the smiling pragmatist who cuts cards with the Devil who flatters him and invests in Krupps mechanized warfare in the name of “profitable industry” at any price to save money.

Péladan’s first three “constitutions” should suffice of his symbolic transformation of medieval language and charitable intention, which one might describe as ironic parody were those words not alien to Péladan’s nonskeptical, passionately ardent yet playful spirit:

I - The lay order of the Rose-Croix of the TEMPLE and of the GRAAL is a confraternity of intellectual Charity consecrated to the accomplishment of the works of mercy according to the HOLY SPIRIT, which it exerts to augment the Glory and to prepare the Reign [of the Holy Graal].

II - Soulfully, it gives hunger and thirst for the IDEAL to those whose only guides are instinct and interest; and that is the orientation of others towards the light.

Hospitalize the errant and indecisive hearts, comfort them and reveal to them their path; and that is the discernment of vocations.

Clothe with beauty and with means the imperfect or weary aspirations; and this is a correction of the specializations.

Visit the sick of will and cure them of the dizziness of passivity; and this is a cure for moral anaemia.

Console the prisoners of material necessity and obtain for them cerebral life; and this is a mental charity.

Redeem the captives of prejudices and emancipate opinion, of the country, of the race; and that is an abstract accomplishment of another.

Bury the august dead in pious commemorations and repair the wrongs of destiny; and that is of the ideal sculpture.

III - Spiritually, it [the Order] instructs those who ignore the Standards of Beauty, of Charity, and of Subtilty, following their functions, and that is the Board of intellect.

Retake from every holder of social power the attacks against the Standard and the tradition; and that is the Ardent surveillance.

Counsel those who are in danger of the sin against the Holy Spirit in misusing their faculties or their gold; and that is the fraternal correction.

Console the Holy Spirit of human stupidity in enlightening experience by the mystery of faith; and that is a concordat between religion and science.

Personally support all the troubled in order to have the right to defend the idea; and that is abnegation to the profit of the Word.

Pardon to all his offenders, but not to the offenders of Beauty, Charity and Subtilty; and that is the chivalry of ideas.

Pray to geniuses as saints and practice admiration, before being illuminated; and that is the meeting-point of culture and mysticism.6

These words constitute about a fifth of the Constitutiones Rosae Crucis templi et spiritus sancti ordinis that opens: “We, by the divine mercy and the assent of our brothers—Grand Master of the ROSE+CROIX DU TEMPLE ET DU GRAAL; In Catholic communion with JOSEPH OF ARIMATHEA, HUGUES DE PAYENS and DANTE”—and which draws toward its close with the 35th constitution, in which we learn that the, presumably otherwise “invisible,” brotherhood “manifests itself annually in March–April, by: first, a Salon of all the arts of design. Second, an idealist theatre, until it can become hieratic. Third, auditions of sublime music. Fourth, clean conferences to awaken the idealism of the worldly.”7

It ought to be clear from the above that Péladan’s Order was essentially a conceptual Order, a kind of ideal Church of Aesthetics, a House of the Holy Spirit of Art, stubbornly set within the Catholic communion and knowingly beneath an ecclesiastical hierarchy that has not asked for it, nor will understand it. In no wise was Péladan’s intention to compete with de Guaita and Papus’s Order. Being ideal, and practically “virtual,” it sets itself above such considerations. In fact, it is in spirit much closer to Johann Valentin Andreae’s original “ludibrium,” or serious fiction, of an “invisible brotherhood” bringing healing wisdom to the starving souls of broken Christendom, than subsequent historical attempts to incarnate that conception in Masonic or para-Masonic forms. As Péladan says, it is a confraternity, and confraternities were formed by laypeople to gather about objects of beauty or sacredness performing works of mercy as being useful and sanctified by God. Indeed, confraternities represent the probable factual origins of Freemasonry, before the Reformation split the Catholic Church. Importantly, the text defines the “orthodoxy” of the Order as “Beauty,” the Platonic ideal expressed in the Book of Genesis when the Elohim sees that the creation is “good.” Goodness and Beauty, relate to Truth (the Ideal), where Beauty is the path, and Goodness the life; thus: “I am the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6). This is the way to the heavenly Father. Hence, Péladan can speak of “Art-God.”

THE MANIFESTATION

The Figaro article trumpeted the artists Péladan wanted and expected to see at the R+C Salon: “the great Puvis de Chavannes,” Dagnan-Bouveret, Merson, Henri Martin, Aman-Jean, Odilon Redon, Knopff, Point, Séon, Filiger, de Gusquiza, Anquetin, the sculptors Dampt, Marquest de Vasselot, Pezieux, Astruc, and the composer Erik Satie.

Having been a regular visitor to Le Chat Noir (though its director, Rodolphe Salis did not like Péladan, a dislike reflected in the attitude of Le Chat Noir’s eponymous periodical) and to Bailly’s bookshop in the rue de la Chaussée d’Antin, Péladan was in an excellent position to entice the practically unknown young genius and Vice Suprême admirer Erik Satie into the fold as official composer (“maître de chapelle”) to the Order.

Satie’s formal connection with the Order dates from 1891 when Satie wrote about a minute of music known as the Première Pensée Rose+Croix. On 28 October of the same year, Satie signed the manuscript of his short “leitmotif” for Péladan’s tenth Décadence Latine novel, Le Panthée (The Panther). The score was reproduced in facsimile on the book’s frontispiece, along with an etching by Khnopff. Satie then wrote a hymn, Salut Drapeau, at Péladan’s request, for his play Le Prince du Byzance. More works for the Order would follow. The Figaro article trumpeted the composer of the trumpet fanfares that would open the Salon: “Among the idealist composers that the Rose-Croix will shed light on, it is proper to mention Erik Satie again, of whose work one will hear the harmonic suites for Le Fils des Étoiles and the preludes to the Prince de Byzance.”

Having secured a “house composer,” Péladan promised to go to London to secure the participation of Burne-Jones, Watts, and five other Pre-Raphaelites. Germans Lenbach and Böcklin would also be invited.

The Salon would not accept all subjects. Unacceptable were “all contemporary, rustic or military representations; flowers, animals, genre history-painting, and portraiture-like landscape.” Landscape was only acceptable if it reflected the genius of Poussin, presumably because Péladan recognized in Poussin’s works ideal, symbolic, and occult value, rather than simply attempts to render the countryside “as it was” or even “as it felt.” Welcome was “all allegory, legend, mysticism, and myth and even the expressive head if it is noble or the nude study if it is beautiful. You have to create BEAUTY to get into the Salon de la Rose+Croix.”

The arbiters of acceptability would be the Magnifiques of the Order, but the final word was for the Sâr, because in a proper Order, someone has to have the last word, and it should be the Master’s, as in all works of Art. In respect of which, portraiture was out, unless it was a portrait of the Sâr, itself a commitment to the Ideal. “The 10th March 1892, Paris will be able to contemplate, at the Durand-Ruel Gallery, the masters of which it is unaware; it will not find one vulgarity.” Should there be any profit from the shows, it would go to the costs of republishing the Treatise on Painting by Leonardo da Vinci, “the divine Leonardo” whose work was “so necessary to artists.”

“Contrary to what one reads in the papers, no work by a woman will be accepted because in our renovation of aesthetic laws we faithfully observe magical laws.” Impossible to swallow today of course, but the tradition behind the proscription of women’s art came from the traditional magical axiom of the feminine as passive, serving as muse and receiver, and the masculine as creative and generative (the king-magus role), the male as sacrificer of creative seed (the priest-role), the female as nurturer, and the prejudice that the lone or independent female seeks to dominate the male when in company, thereby imperiling individuality, the cornerstone of the Order. To which strictures, Susan Sontag, Germaine Greer, Yoko Ono, and many other women would doubtless cry: “Bullshit!” Not all that long ago, but different times, for sure.

As it turned out, Puvis de Chavannes declined to support the event, as did academicians Dagnan-Bouveret and Luc-Ilivier Merson. Art historian Robert Pincus-Witten reckoned the latter two, being market-leaders in academic religious art, declined to jeopardize their position with the controversial outsider, Péladan.8 Puvis de Chavannes actually protested “with all my strength” in the evening’s Figaro that his name was being used to bring others to the event, but he was an influence through his pupils Séon and Osbert. After that rejection, Péladan cooled toward his onetime art hero.

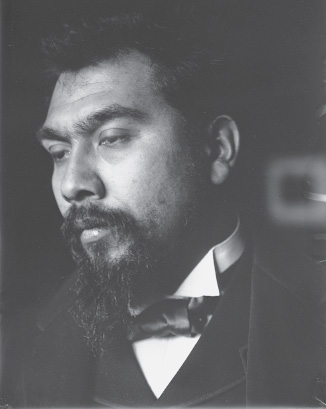

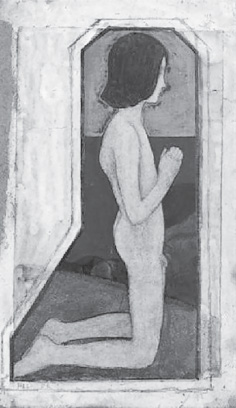

Antoine de La Rochefoucauld was doubtless disappointed that Maurice Denis did not exhibit with the Rose-Croix, though the Pont-Aven school was represented by de La Rochefoucauld himself, his brother Hubert, and by Émile Bernard and Charles Filiger. Apparently, Maurice Denis would not subscribe to an aesthetic that included both allegory and Symbolism within categories of the Ideal. According to Denis, the symbol “suggests ideas by beauty alone.”9 Perhaps surprisingly, Odilon Redon preferred to be out, and neither Félicien Rops nor Gustave Moreau appeared in the two first Salons de la Rose-Croix; pupils of Moreau would enter the third.

Fig. 10.10. Drawing of Alexandre Séon by Puvis de Chavannes, Musée des Beaux Arts de Lyon.

Less surprising was the attitude of much of the Press. While La Revue Indépendante praised highly Péladan’s use of Plato’s Symposium in his aesthetics,10 critic Gonzague-Privat dismissed Péladan in L’Evénement (November 2, 1891) as “the only Frenchman with the right of addressing the Ideal in familiar form. . . .”11 Predictably, La Plume struck hard on 15 November when S. Mueux cast the socialist hatchet into Péladan: “We equally mock the Thaumaturges as the Myths, the Myths as much as the Magi, the Magi as the Saints, the Saints as the Angels, the Angels as the elves, the elves as the sorcerers, the sorcerers as the alchemists, the alchemists as the occultists, the occultists as the Knights Templar, the Knights Templar as the Free-Masons, the Free-Masons as the Illuminates [etc.].”12

Nevertheless, as Pincus-Witten has observed, Péladan was truly in touch with an “urge” deeply set in the period. François Paulhan’s 1891 book Le Nouveau Mysticisme cited Péladan along with Huysmans and Bourget as significant mystical influences, while G. Albert-Aurier’s classic assessment of Symbolism in his “Le Symbolisme en Peinture, Paul Gauguin,” which appeared in the Mercure de France (February 1892), and which indicated the five necessary features of Symbolist Art, corresponds closely to Péladan’s theories, though not in all parts. Aurier’s categories are now established, that is, that Symbolism is: (1) Ideological; (2) Symbolistic (idea expressed in forms); (3) Synthetic; (4) Subjective (objects are not merely objects, but signify ideas); and (5) Decorative in function. According to Pincus-Witten: “Péladan’s attitudes and actions demand reappraisal because, in theory, they relate to aspects of that which is most modern in their period. The crucial difference between Aurier and Péladan is that Aurier had the genius to recognize these principles in the art of Paul Gauguin whereas Péladan’s were applied a priori to a host of less illustrious and, in many cases, inept artists.”13

I wonder what Péladan would have said in his defense concerning the last sentence. The “inept” may only be seen as such in retrospect. Péladan was trying to encourage young artists to the cause. It is not unheard of, when opening up a new continent, to say: “Bring me your rejects! I can mold them! We have the dream!”

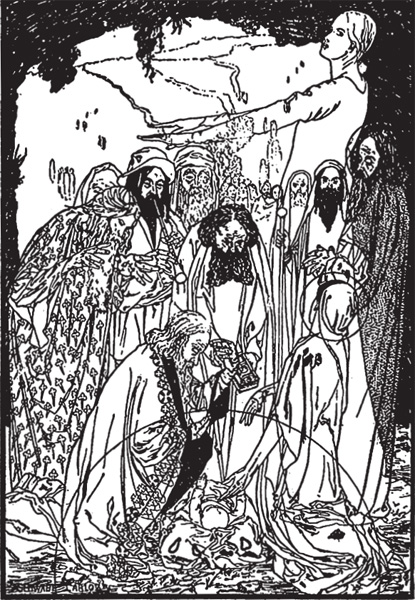

Posters for the event appeared in Parisian streets in early 1892. Reproduced many times, Swiss Symbolist Carlos Schwabe (1866–1926), designer and printmaker, had made a big hit with Péladan, for the catalog of drawings for the exhibition contains eleven of his works, all resembling Pre-Raphaelite influenced illustrations in works of fantasy and mythology, set in medieval times, though Pincus-Witten regards them as Botticellian. Ten came from L’Évangile de l’enfance, published the previous year in the Revue Illustrée. Schwabe produced a gem for the poster (see color plate 31). The theme is ascent from the mire of the world toward the ideal. We see a nude mired in the material swamp, slime dripping from her fingertips. She looks half asleep as well as literally “half-soaked.” She gazes vaguely to two defined female figures on a celestial staircase—Schwabe’s inspiration may just have been Blake’s Jacob’s Ladder. The lower female hands a lily to the transparent-seeming figure slightly above her. She is Idealism, and holds a heart in her hand. She receives a beam of light directly from above. She then is the Greek nous, or Latin intellectus, the “higher reason” that is spiritual mind.

Lilies and roses, flowers of the Virgin, are strewn on the stairs. The Ancient & Accepted Rite’s 18th Rose-Croix degree employs similar stage settings as the knight-mason’s voyage reaches its climax. The picture is framed by crucified roses on altars familiar to any Knight of the Pelican and the Eagle. The design is basically allegorical and emblematic rather than strictly Symbolist. It works.

Fig. 10.11. Carlos Schwabe’s illustration from L’Évangile de l’enfance, Salon Rose-Croix catalog 1892

In fact, it worked almost too well. On opening day, Thursday 10 March 1892, the police had to stop traffic between the rue Montmartre and the Opéra, until past five in the afternoon. Larmandie counted 274 carriages; more than 22,600 visiting cards were left. According to Larmandie’s record: “The real, the only food, was an immense enthusiasm, an unshakeable faith in the certitude of an apotheosis, the deep-rooted belief that a new life opened for art and that we were the predestined workers of a regeneration without precedent.”14

It had taken three days and three nights to hang the exhibition, with no time to stop to eat, hence the remark above about what drove the organizers. Two thousand press invitations went out, and many invitations to private individuals. The Salon provoked extraordinary levels of curiosity. Larmandie was gratified by the number of French nobles who came to gaze: “the premier 200 names of the French Armorial.”15 Government ministers, the count of Münster, poetess Anna de Brancovan, Comtesse de Noalles, Lord Dufferin, the Duke of Mandas, Count Radziwill, two Gramonts, Montesquiou, Maillé—they all wanted to know what was happening.

Though he had declined to exhibit, Puvis de Chavannes, a friend of Alphonse Osbert (who did) came to see, as representative of the National Society of Fine Arts, as did Gustave Moreau. Even the Naturalist opposition, Émile Zola, came for an hour. The Society of French Artists held aloof. Verlaine arrived, leaving a bon mot before he left: “Yes, yes, agreed, we are Catholics . . . but sinners.”

“Clearly correct,” added Larmandie!16

In the light of the collective sin, we may note the gallery opening was preceded by a Solemn Mass of the Holy Ghost celebrated at 10 a.m. at the church of Saint Germain l’Auxerrois at 2 place de Louvre, where the “Prelude,” the “Last Supper of the Grail,” the “Good Friday Spell,” and the “Finale of the Redemption” from Parsifal by the “superhuman Wagner” were played. The Mass was preceded by “three fanfares of the Order composed by Erik Satie for harp and trumpet.”17 The organizers and their special guests then took carriages a kilometer north back to the gallery at 11 rue le Peletier, close to the junction with the boulevard Haussmann in the 9th arrondissement, 400 meters or so east of Bailly’s bookshop.

Fig. 10.12. Gustave Moreau, self-portrait

Entering the gallery Durand-Ruel, normally no friend to Symbolists, but temporarily won round by La Rochefoucauld’s charm and wallet, visitors were first confronted by a long corridor in which was hung a large Manet. This attracted jeers from many “idealists” who had cottoned on to the idea of a regrettably “low ceiling” of vision attempted by Impressionism. Nevertheless, the objects of so much Impressionist delight were everywhere: the gallery was filled with flowers. Those who arrived in the first two hours were charged a hefty gold Louis for the privilege of ingesting their fragrance at its purest; the rest paid twenty francs, worth roughly thirty dollars at today’s prices, and enjoyed the fragrance of one another, confronted with dozens of pools of eternity, or at least the palpable longing for it.

The works on show conformed to Aurier’s idea that Symbolist art should be decorative, for decorative art allows for abstraction and representation both, and their combination kept symbolism in its romantic swaddling bands from the coming austerity of “pure,” rigorous abstraction that hit the art world like a sermon from John Calvin as the twentieth century unrolled its barbed carpet.

Here are the painters and sculptors who exhibited at the first Rose+Croix Salon, many now forgotten, but caught in this moment of history on the rue de Peletier, glowing briefly, like flies in amber: Edmond François Aman-Jean, Atalaya, Émile Bernard, Gaston Béthune, Émile-Antoine Bourdelle (sculptor), Jean-Louis Brémond, Eugène Cadel, François-Rupert Carabin, Maurice Chabas, Louis Chalon, Alexandre Charpentier, Albert Ciamberlani, Pierre-Emile Cornillier, Émile-Antoine Coulon, Jean Dampt (sculptor), Vincent Darasse, Jean Delville, André Desboutin, Marcellin Desboutin, Rogelio de Egusquiza, Charles Filiger, Eugène Grasset, Edmond Haraucourt, Ferdinand Hodler, Icard, Isaac-Dathis, Georges-Arthur Jacquin, Fernand Khnopff, Leon-Charles de LaBarreDuparc, Lambert Fovras, de La Perche-Boyet, Antoine de La Rochefoucauld, Hubert de La Rochefoucauld, William Lee, Paul Legrand, Georges Lorin, Lowenberg, Edouard de Malval, Henri Martin, Baron de Massy, Charles Maurin, George Minne (sculptor), Auguste Monchablon, Auguste de Niederhausern-Rodo (sculptor), Charles-Jean Ogier, Alphonse Osbert, Lord Arthur Payne, Jean-Alexandre Pézieux, Armand Point, Gaetano Previati, Emile Quadrelli, Emile-Paul de Raissiquier, Pierre Rambaud, Richard Ranft, Raybaud, Léopold Ridel, Lensbaron Arild Rosenkrantz, Emmanuel de Sainville, Léopold Savine, Carlos Schwabe, Alexandre Séon, Albert-Gabriel Servat, Léon-Julien Sonnier, J. M. Stepvens, Tonnetti-Dozzi, Jan Toorop, Albert Trachsel, Félix Vallotton, Pierre-Théo Wagner.

Of the artists who exhibited at the first Salon Rose+Croix, Pincus-Witten regards Séon (1855–1917), Osbert (1857–1939), and Armand Point (1861–1932) as most representative of the “hard-core Rosicrucian style,”18 but I doubt if he would object if we added to that hard core Fernand Khnopff (1858–1921), Jean Delville (1867–1953), Jan Toorop (1858–1928), and Émile Bernard (1868–1941), whom he and posterity regard as important artists.

It is not, however, altogether clear what we might mean by a “Rosicrucian artist.” The guidelines for entry, though they resisted realism—Péladan had declared the Order’s intention to “ruin Realism”—were quite broad, from the religious and mystical, to the mythical and the dreamlike, with the overall caveat of idealism, beauty, symbolic and allegorical spiritual value. Perhaps there is simply something particularly graphic and original about the seven named artists above that we, through seeing their works in books dealing with the period or its occult aspects, cannot help linking with Péladan’s intended movement. Posterity seems to judge them anyway as being about the best artists of the crop, able to create images of great power, suggestiveness, and distinction from the complex and sometimes ambiguous aims of Péladan: aims that were after all, characterized by a certain aggressive destructiveness, though his armory was intended to be the undeniably beautiful. Here of course we encounter the eye of the beholder, and the strangeness of many of the images, and their occulted subject matter or inspiration, makes it hard for some people to see them as unequivocally beautiful. I expect in time, a few other names than those familiar to us will emerge with a hidden gem or two. Evolution in art is one thing; evolution in taste is another.

Fig. 10.13. Émile Bernard (1868–1941), self portrait

The arbiter perhaps should be whether the artists themselves were committed to Rosicrucian spiritual or occult, gnostic principles, and here it gets very difficult, for not only did Péladan transform the meaning of the word Rosicrucian into a broad Catholic aesthetic, but we also find many other Symbolists who did not exhibit, but who were moved by the esoteric spiritual currents of the time in different ways at different times. Paul Sérusier, for example, was spiritually involved with Christian esotericism and the Rosicrucian traditions, but he did not wish to associate with Péladan’s “brand.” Similar remarks apply to Maurice Denis.

There is nothing dreamy or symbolic about Alexandre Séon’s superb oil portrait of Sâr Joséphin Péladan, now in the Musée de Beaux Arts, Lyon (see color plate 20). It shows him in a pleated gray robe with wide sleeves that might last have been aired 400 years earlier, in profile, his hands gently by his side, attending as it were to some ideal conception off canvas. It radiates the man’s idealized character projection wonderfully and is perfectly representational, full of immediacy and calm, though co-exhibitor Félix Vallotton found it embarrassing, partly on account of Péladan’s dress. Séon’s other works for the Salons tended to be his disconcerting illustrations for Péladan’s novels; they too have that very curious, slightly off-putting yet intriguing characteristic of the “Décadence Latine,” chimeras abounding.

The Belgian Jean Delville is probably the most directly accessible “Rosicrucian” artist, arguably because of his almost photographic, or fantasy-cinema, draftsmanship combined with precise imagery, his works having since appeared on record sleeves and books of magic. It is interesting that the almost blazing, magically transfixed face and electrified red hair of his startling Portrait of Mrs Stuart Merrill (1892) has provided the cover for Jullian’s book on Symbolist art Dreamers of Decadence, as well as anthologies of occult poetry. Oddly perhaps his quite brilliant crimson dip into hellish streams of human lava, Satan’s Treasures (1895), which combines magic, mystery, eroticism, and dream, was used as a very effective record cover for a collection devoted to Satie, Ravel, Fauré, and Debussy issued in the late ’70s. I say “oddly” because the sleeve notes seemed to be under the impression that these composers were all somehow Impressionists, when the cover spoke loudly of that Symbolist Occult Paris I here describe!

Fig. 10.14. (top) Portrait of Joséphin Péladan by Alexandre Séon; (bottom) Alexandre Séon frontispiece for Péladan's novel L'Androgyne

Fig. 10.15. Jean Delville (1867–1953); the artist dressed for Masonry

Delville was certainly Rosicrucian in philosophical outlook, if by that term we imply the mélange of late nineteenth- to twentieth-century neo-Rosicrucianism of the Theosophically imbued strain. A member of the Belgian Group, “Les XX,” he split with former colleagues in 1892 over his commitment to Péladan’s style of idealism. He then copied Péladan’s outlook, from Wagner to the Pre-Raphaelites, to Leonardo with the new Belgian group Association Pour l’Art. Delville undoubtedly desired to see the world awaken to the value of esoteric tradition. Under Russian composer Scriabin’s influence, he would become a convinced Theosophist, and later a disciple of Krishnamurti. Delville contributed three works to the 1892 Salon, among which Le symbolization de la chair et de l’esprit (Symbolisation of the Flesh and the Spirit) is quintessentially Symbolist in feel. It depicts a male figure trying to rise, amid swampy weeds of dark emerald, from the grip of the female figure whose peachlike erotic bottom is prescient of Gustav Klimt’s in-your-face “Red Fish” posterior of 1903, though Delville’s “flesh” figure has a serpent’s tail: all a little obvious, perhaps, and more allegory than symbol with not a little hint of erotic misogyny, or having one’s Jesuitic cake and eating it.

Émile Bernard of the Pont-Aven school would grow to resent the attention given exclusively to Gauguin as the latter took certain Pont-Aven sensibilities to the level of fame, while the pioneers languished in relative obscurity, Filiger in particular. Bernard contributed to the first Salon, Christ Carrying the Cross, an Annunciation, and Christ in the Garden of Olives, works displaying a folkloric style, curved contours, and flattened perspectives, all informed by deep feeling. The designs would have made outstanding medieval friezes and tiles.

Like Bernard, part Dutchman, part Javanese Jan Toorop (1858–1928), born in Java’s Poerworedjo, promoted respect for the work of van Gogh, an effort assisted by his being chosen president of the First Section (Fine Arts) of the Haagsche Kunstring in December 1891. In 1884 Toorop had journeyed to London with Symbolist poet Émile Verhaeren (1855–1916), there to be influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites and charmed by William Morris’s art and socialism, as was Rops. Returning to Paris, Toorop met Péladan and Redon.

Fig. 10.16. Jan Toorop (1858–1928), photograph by Willem Witsen

Inspired by mystical Theosophy, magic, fantasy, and religious ideals, Toorop hoped to make the Haagsche Kunstring a focal point for promoting Nieuw Kunst, the Dutch equivalent of Symbolist-dominated art nouveau or the Austrian Jugendstil. Familiar with Khnopff, Ensor, and other Symbolists, Toorop organized an exhibition of Les XX and the split-off Association pour l’Art in July–August 1892, the latter in association with Jean Delville. Péladan would come with Paul Verlaine to address the new Dutch and Belgian artists in November. Toorop contributed two works to the Salon Rose-Croix in March 1892 (nos. 175–76: l’Hétaire and Une generation nouvelle), and began work on his remarkable The Three Brides, highly influenced by Péladan’s blend of Catholicism and Rosicrucian alchemy, and painted in a unique angular style, blended with art nouveau arabesques and symbolic figures sacred and profane, influenced by Javanese puppetry and spirit forms. Toorop became a Roman Catholic in 1905.

Alphonse Osbert’s phenomenal, and very large, portrait—or vision—of Saint Geneviève, called simply Vision (see color plate 33), could be the gateway to the aesthetic that emerged from the first Salon and that can still communicate with us its compelling yet simultaneously repulsive force. Vision was, however, not quite ready for the first R+C+C+ Salon, which had to be content with Osbert’s Hymne à la Mer, a work touched by the spaced mystery of Puvis de Chavannes, but considerably warmer. In a golden light, more dawn than dusk, a nymph with a lyre holds her hand out toward the lapping waves, touching the air, casting a spell of her longing, sung for the infinite, the sublime, the eternal. She is like a column, dignified, the pleats of her Grecian dress like flutes of a votive pillar. The painting could be an illustration of the first verse of Rimbaud’s unforgettable proto-Symbolist poem L’Eternité (1872):

Fig. 10.17. Paul Verlaine in the Café François in 1892, photograph by Paul Marsan Dornac

Elle est retrouvée.

Quoi?—L’Eternité.

C’est la mer allée

Avec le soleil.

She [or “it”] was found again.

What?—Eternity.

It’s the sea gone

With the sun.

Osbert was an associate of the Salon des Indépendants, from among whose number several contributed to Péladan’s dream: Bernard, Filiger, and Séon. Osbert has been called one of the “Nostalgiques” by Indépendant historian Gustave Coquiot, along with the Swiss Albert Trachsel who exhibited at Durand-Ruel’s sole excursion into the Rose+Croix aesthetic in 1892. Osbert borrowed a pointillist technique from his recently deceased friend Georges Seurat, who in his last days allegedly regretted departing from symbolist poetics for more realistic subjects, ironically blaming J.-K. Huysmans for the fatal transmission, while Huysmans himself had made the reverse conversion to symbolist-decadent modes, resulting in full Catholic conversion. When the critic Fagus criticized Osbert’s work as being literary, Osbert defended Idealism: “art lives only by harmonies . . . it must be the evocator of the mystery, a solitary repose in life, a kin to prayers . . . in silence. The silence which contains all harmonies . . . art is therefore, necessarily literary, according to the nature of the emotions experienced.”19

Nostalgia is a clear characteristic of the works displayed: nostalgia not only for times past of idealism, romance, spiritual mystery, classicism, the antique, but also personal nostalgia for moments when touched inwardly by the elusive Absolute, and perhaps above all, that peculiarly gnostic nostalgia for spiritual home, somewhere to fly to, not of this world. But the yearning for that which is just out of touch, or even remote, inaccessible, can make one feel rather sick as well as painfully comforted by the hint of a presence with its glint of fugitive hope. Is there not something a little sickly in Khnopff’s chimeras? Perhaps it was a quality within his sister’s face when juxtaposed with chimeras and the fatal stillness of the compositions. She appears time and again in Khnopff’s works, and probably in the Sphinx he provided for the 1892 Salon. His art, even when bathed in unearthly quietude, seems to presage some oncoming catastrophe, like electric air and amber light as birds stop singing before a storm, for which all the artistic evidence from the late antique and Byzantine worlds testifies: the crumbled empires, whose art, once loved in function now sits clean on museum pedestals or mildewed as garden ornaments. The world in which the winged head of the god really meant something has been destroyed: its testimony mute as a stringless lyre. If its spirits would speak, it would be in the darkness of a séance chez Lady Caithness. There is an enormous tension in the best works of the Rose-Croix Salon; the shadows are advancing. Péladan himself was aware that the effort might constitute as much a last stand before barbarism smashed the decadent banquet as the dawn of an Age of the Grail. Those who hated the aesthetic dismissed it as superficial in its mystical objectives and as unwholesome in its forms, the peril of youthful indulgence in introspection. Péladan hated the army, which contempt he transformed into a valuable aesthetic rule: a “patriotic” painting does not have to be a military subject, but rather a very good painting that gives credit to its place of origin.

Fig. 10.18. Fernand Khnopff ’s Pallentes Radere Mores (Immoral People Turn Pale under the Lash of Satire), frontispiece to Joséphin Péladan’s Femmes Honnettes! (Honest Women!)

Perhaps one of the most direct statements of the value of the 1892 Salon’s approach to painting came from one whose work was exhibited there, Swiss painter and Nabi, Félix Vallotton (1865–1925). Vallotton entered the Salon with a heavy, skeptical heart, writing that: “Not much good is to be expected from Péladan and his crusade. The Sâr already has amply proved that he only knows how to be dangerous to the causes he represents.”20 The experience of the Salon transformed Vallotton’s perception of Péladan:

Instead of the anticipated mystification, the open-minded visitor was astonished to find a well-arranged hall, nicely composed, wherein very good work appeared with dignity with no other showing-off . . . a breath of youth and life, so that, whether one wanted to or not, sympathy was won; all the works shown, even beginners’ works, denoted audaciousness and sincerity. The air that one breathed on entering there bore witness to so much faith and loyal effort that we were impressed as by a bravura melody.

One can be utterly indifferent to the Sâr, the sweet inoffensive Sâr, for his manias, for his costumes, and his ridiculousness, but after the smiles one nevertheless owes him a debt of gratitude for having put before the public the chance of judging so much valiant and tangible work.21

Vallotton seemed to recognize there were two Péladans. This anyway was the conclusion of Paul Verlaine who would travel with Péladan to Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp, and Louvain in November 1892, as Péladan evangelized the Rose+Croix cause to enthusiastic Dutch and Belgian artistic idealists. Verlaine appreciated the man of profound talent, but distinguished him from the doubtless sincere but overbearing “sectary” that delighted in being regarded as Sâr and Magus. This distinction has, interestingly, been made of Aleister Crowley, who with hindsight, seems to have been in some respects a curiously English replacement for the declining Sâr of the Edwardian era. In short, Péladan’s error may be seen as his having demanded, rather than commanded attention. Such was his own assessment of his personal failure as the 1890s drew to an end, though as with so many things, time will tell.

Whether it was a result of La Rochefoucauld’s getting tired of the Péladan self-promotion or some deeper cause, we cannot be sure, but the unhappy rift that opened up between the two men before the first Salon was over would reflect badly on Péladan. When a man’s friends leave him, what have the enemies left to prove?

The obvious causes of the rift came out of organizational differences, chiefly with regard to the soirées that began on 17 March and that Péladan had planned with great care, even to the extent of forming his own theatrical company to add a Wagnerian totality and synthetic sparkle to the proceedings. For the Salon was intended as a complete artistic gesture: in paint, in music, and in dramatic word, for the three combined opened the path to the reintegrated spirit.

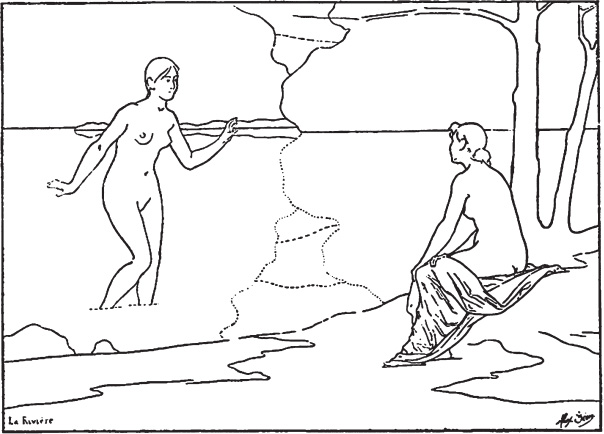

Fig. 10.19. Alexandre Séon’s La Rivière, clearly influenced by Puvis de Chavannes, from the 1892 Salon Rose-Croix catalog

However, as we have noted, there had developed a kind of ideological rift as well. The Commanders all realized that the Symbolism reflected in the Salon had two main schools. First there was a kind of “impressionistic” symbolism, nature-sensitive, obviously religious, almost pietistic, favored by the Nabis; then there was what was recognized as a kind of “English” Symbolism, or more particularly, a classical kind.

The latter reflected enthusiasm for Puvis de Chavannes, Gustave Moreau, Leonardo, and of course the Pre-Raphaelites. The “Archonte,” La Rochefoucauld, who would support the struggling Pont-Aven artist Charles Filiger with a stipend in gold Louis, was personally committed to the Nabis, and obviously asked himself why he did not favor them alone. When the “classicists” seemed to dominate the argument, he was upset.

Fig. 10.20. La Prière by Charles Filiger (1863–1928)

Another cause for annoyance was that the Gallery had been leased in La Rochefoucauld’s name, meaning he had legal rights to direct the Salon artistically. He did not have to submit to the “Grand Master,” and as an aristocrat from a distinguished family, he of course would never have taken the Order hierarchy any more seriously than he had to. If he had to pay, it would be for all that he believed in, or not at all.

Things began to get seriously out of hand when the Archonte became fully aware of the costs of the musical soirées, which he was expected to pay alone.

The Soirées de la Rose-Croix opened on Thursday 17 March, with seats for 200 at a price of twenty francs. According to the program, first the audience would be entertained by a performance of Palestrina’s Mass of Pope Marcello, sung a cappella by forty voices, to be followed by a speech in praise of Palestrina by the “SÂR,” after which a fragment of the one-act opera La Sonate du Clair de Lune (libretto by Judith Gautier) would be sung by the composer of its music, Benedictus. Judith Gautier (1845–1917), Théophile Gautier’s daughter and estranged wife of Catulle Mendès, enjoyed a long-running relationship with Dutch composer Ludwig (Louis) Benedictus (1850–1921).

Fig. 10.21. Judith Gautier (1845–1917)

Judith was a friend of Wagner while her partner Benedictus had successfully conducted Wagner’s music in Paris in 1882 and 1889. The opera featured Beethoven as its hero. The climax of the evening would be Péladan’s own play Le Fils des Étoiles (The Son of the Stars), a “Kaldaean Wagnérie” (“Kaldaean” meaning of the culture of the Chaldaean Magi of ancient Babylonia). The three acts of this play would be accompanied by “an harmonic suite” by Erik Satie.

Péladan was apparently so proud that his play had been turned down by Jules Claretie of the Comédie Française on 3 March that he printed Claretie’s amiable rejection letter in the program for all to see. La Rochefoucauld obviously saw this curious demonstration in different terms when the actual performance attracted bad notices. The Archonte refused to pay the large sum required for the billed repeat performances of the play and musical score on the second soirée of 21 March and what would have been the fourth soirée (undated on the program).

Furthermore, for some unknown reason, perhaps due to the perceived adulterous relationship of Judith Gautier and Benedictus, La Rochefoucauld refused to have conductor-singer Benedictus involved at all. The first night did not feature the Gautier-Benedictus opera fragment. Clearly, this high-handed override is where the aristocrat’s legal status as artistic dictator really got Péladan’s goat, for the Sâr was forced into having Benedictus smuggled into the now rescheduled second soirée and announced as “our Capelmeister,” a title he had already given to Erik Satie in an inscribed copy of one of Péladan’s Salon reviews. Péladan was faced with the unpleasant news that the third night, dedicated to Wagner, had, a week before the performance, been taken out of Benedictus’s hands and given by La Rochefoucauld to the famous conductor, Charles Lamoureux. It was rescheduled for 5 April.22 The Count tried to assure Péladan that Benedictus had left of his own free will. Péladan was understandably beside himself and declared La Rochefoucauld “anathema,” excommunicating him from the Order before starting legal proceedings.

On the night of the Wagner concert, what appeared to be a bearded man entered the gallery during the “Siegfried Idyll,” asking for Commander Larmandie, but Péladan had ordered Larmandie “to retire immediately and definitively from Durand-Ruel, treacherously rented in the name of La Rochefoucauld.”23 Catching sight of the count, the bearded man began showering him with insults: “La Rochefoucauld, you are a felon, a coward, a thief.”24 A scuffle ensued, with the bearded man being thrust through a glass door that shattered, bringing the orchestra to a standstill, whereupon the audience stood up and an attempt was made to arrest the instigator of the fracas. In the mélêe, the man’s beard got pulled off, revealing a Magnifique of the Order. It was Commander Gary de Lacroze, and the police took him away, much to the delight of “Willy” (Henry Gauthier-Villars), the Chat Noir’s “Ouvreuse [Usherette] du Cirque d’Eté,” arch-critic of Satie and Péladan, who observed the goings-on with relish. Willy—soon to marry twenty-year-old novelist Colette (author of Gigi) in 1893—would continue attacking Satie for over a decade. According to Gauthier-Villars’s account, La Rochefoucauld reassured the discomfited audience: “Ladies and Gentlemen, that was a friend that Sir—not Sâr—Péladan sent over to interrupt the performance.”25

Fig. 10.22. Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (1873–1954); in 1893 she married Henry Gauthier-Villars, under whose name her first four Claudine novels were published; they separated in 1906, divorced in 1910

Willy was far from the only journalist with an interest in the Salons Rose-Croix. For the record, Firmin Javel submitted a well-considered, detailed, and almost entirely approving review of the Salon to Gil Blas (11 March 1892), picking out Khnopff, Bonnard, Séon (“very remarkable”), and Henri Martin’s tiles for special mention. Anquetin, Brémond, Marcelin Desboutin, Trachtel, and Hodler (“five aged men, almost naked, sitting on a bench and appearing very unhappy, but well ugly”) also impressed the critic. Javel also found Émile Bernard’s Christ in the Garden of Olives and his Calvary moving, while works by Chabas, Dathis (Anaesthetized Sleep), Point, Aman Jean, Bourdelle, and the La Rochefoucaulds also gripped his attention. Javel found the displayed sculptures “magisterial,” commending the graces of Pézieux, Rambaud, Charpentier, Jean Dampt, Rességuier, and Vallgren. “Nothing there,” said the critic, “was banal. There were even works of the first order.” He praised for their “imperious or seductive suggestion” Pézieux’s Virgo and Virgin and Child, Rességuier’s Saint John, Vallgren’s Funerary Urn, and Dampt’s Virginity along with the latter’s little carved head of a child. Rambaud’s Thought pleased Javel, as did the “great composition of a beautiful allure,” The Torrent by M. de Niederhosern, Rodo.

Fig. 10.23. This work by Théo Wagner, Désolation, looks like it could have inspired Munch’s more famous The Scream, painted the following year (1893)

Firmin Javel prefaced his review with a quote from poet and academician François Coppée: “And I have not found this so ridiculous!” Clearly, prejudice against Péladan had suggested it would be otherwise. In the face of beauty, Javel was honest enough to cast aside his preconceptions.

Affiches Parisiennes, April 1892; “Dissolution of Societies” column, dated 24 March:

Deeds under private signature.

Order of the Rose+Croix du Temple

Péladan and La Rochefoucauld

Annual Salon of aesthetic manifestations

Seat: 19, rue d’Offémont,26

With the breach with La Rochefoucauld, Péladan’s dream might have appeared shattered, but Péladan was still ready to live by tooth and claw. He straightened his feathers and took comfort in declaring the Rose-Croix Catholique had in Spring 1892 instigated an aesthetic renewal in France of the scale of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England.

However, it was not only the count who would be lost to the cause. Erik Satie realized at once that with La Rochefoucauld no longer supporting the Order’s official composer, or indeed its aesthetic manifestations, he too must reconsider his position. In June 1893, Satie visited the count. The count sent Satie off to journalist and poet Jules Bois (Henri Antoine Jules-Bois, 1868–1943), soon-to-be editor of monthly review Le Coeur, funded for its short life by La Rochefoucauld. Intrigued by the black arts and mysticism in general, Jules Bois would play a considerable part in the next episode to shock Occult Paris.

Fig. 10.24. Seal of Péladan’s Order of the Rose-Cross, Temple and the Grail