23

SEARCHING FOR THE RARE

LET HIM WHO boasts the knowledge of actually existing things, Saint Basil the Great wrote, first tell us of the nature of the ant.

In meeting Saint Basil’s challenge literally, myrmecologists have explored unusual environments throughout the world and enjoyed unique challenges and physical adventure at its very best. Students of ants have stories to tell, not just to fellow specialists but to anyone interested in the challenges of natural history.

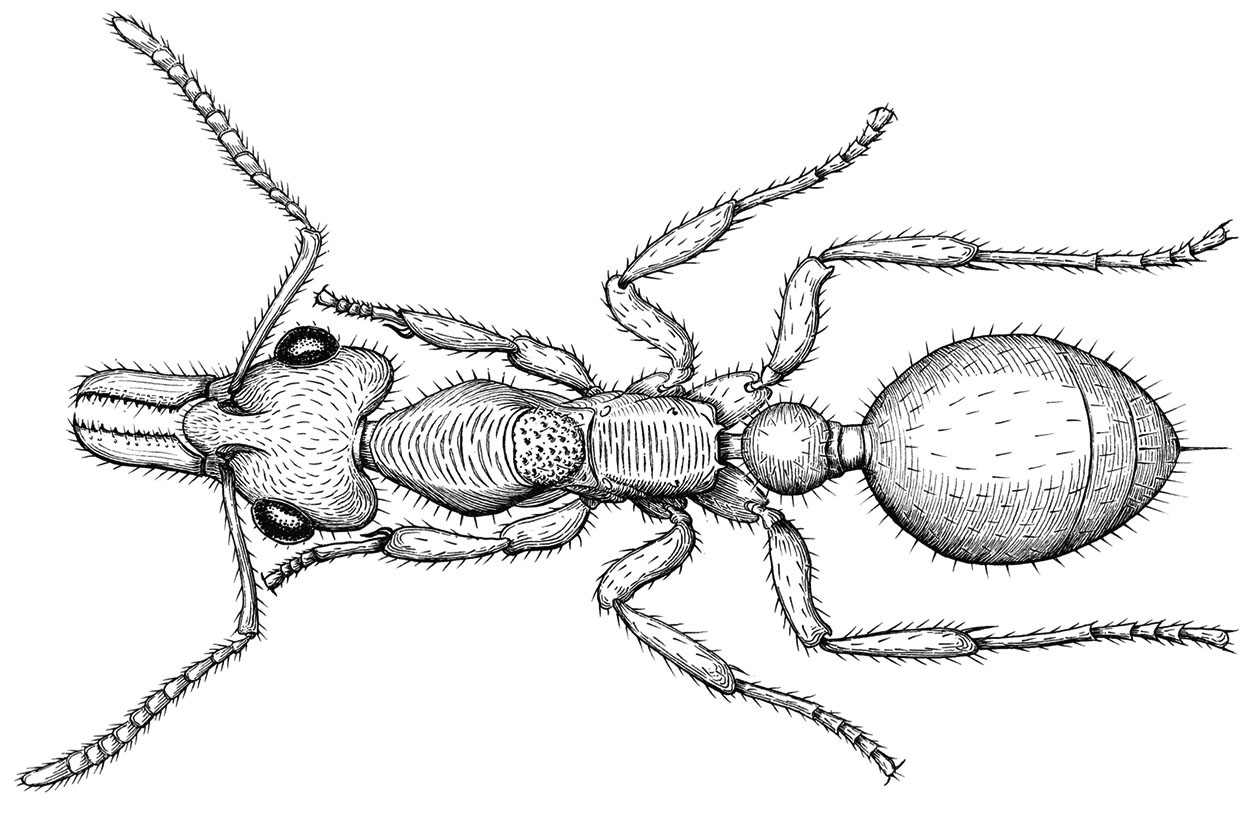

One such story, scientifically among the most important to date, was the search in southwestern Australia for Nothomyrmecia macrops, the most primitive living ant species known at the time. In 1932, a young woman naturalist had collected the first two specimens while on a horseback expedition across the sandplain heath between Esperance to the west and the Nullarbor (translation, “treeless”) Plain to the east. Myrmecologists were fascinated by its wasplike anatomy. Might Nothomyrmecia colonies possess social behavior as primitive as its anatomy, and provide us with clues to the origin of ant societies from ancestral wasps, which we estimated to have occurred over a hundred million years earlier? We needed to study living colonies in order to find out. In the summer of 1954, I went to the collection site with three companions. One was a mechanic to drive our overland vehicle, the second a naturalist from Perth, and the third was Caryl Parker Haskins, in his mid-forties a prominent geneticist, public official, and author of the best-selling book Of Ants and Men. Caryl was an ardent myrmecologist and, as it happened, the leading expert on the ferocious bull ants of Australia, the closest known relatives to the nothomyrmecines.

A camp at night in the boundless Australian outback, with a cooling breeze, whining dingoes circling the campfire in search of scraps of food thrown away, a sense of unknown variety of life in all directions—wilderness in the best sense of the word. I thought, it will never get better than this, especially if we could find Nothomyrmecia.

As night fell on our second day in the field, Caryl Haskins and I walked out into the dark, flashlights in hand, hoping that Nothomyrmecia workers were nocturnal and came out then. We found none, and were soon lost. The sandplain heath had no trails and no local features that offered compass direction. When it became clear that we would have to wait until dawn to find our way back to camp, Caryl looked about for a rock of the right size and shape to serve for a pillow. He carried it into a clearing, lay back, positioned his head, and fell asleep. I spent the night walking around him in widening circles, flashlight in hand, hoping the Nothomyrmecia were nocturnal and I might find workers foraging away from their nest.

No luck, either then or afterward. During the four-day visit, we collected a couple of ants new to science, as well as rare known species, and enjoyed the grandeur of the heathland fauna and flora. In that time we glimpsed one automobile pass along a distant road. On another day a white stallion trotted up close, out of nowhere that we could tell. It stood looking gravely at us for several minutes, then trotted away to disappear on the sandplain heath.

We found no Nothomyrmecia macrops, not a single worker. We were in the right place—double-checked. How could we have failed? Later, after we returned to the States, the news of American scientists searching for what now was called the “dawn ant” spread widely in Australia. It stirred local entomologists into an effort of their own. Australia’s most famous ant should be rediscovered by Australians.

Success, when it came, revealed why we had failed. Robert W. Taylor, a New Zealander working in Australia, who had earned a PhD under my direction at Harvard and was then employed as a government researcher at CSIRO in Canberra, organized an expedition to the original collection site with the intention of scouring the habitats until they came up with the dawn ant.

They left Canberra in the early winter of southern Australia, traveling by automobile from Canberra southwest to Adelaide on the southern coast. On the first night, they camped a short distance beyond the city, in a forest of mallee, a species of dwarf eucalyptus.

There was a chill in the air around the campfire, but not yet sharp enough to halt all activity by the local insects. When dinner was finished and the others were settling down, Taylor ventured into the mallee to collect specimens of the local ant fauna. A short time later, he ran back into camp shouting, “I got the bloody bastard! I got the bloody bastard!”

Nothomyrmecia macrops had been rediscovered, and the Adelaide camp area became the center of Nothomyrmecia field studies thereafter. Colonies were collected for laboratory research. The species, in time, became one of the best known of living ants. The likely early stages of ant evolution were then more securely estimated.

With a relatively dense population of Nothomyrmecia now located, we could ask, Why did my fellow searchers and I fail to turn up even one specimen in our own efforts? The answer soon became clear: we had been searching at the first locality, east of Esperance, in warm to hot summer weather. Taylor and his fellow searchers had chosen comparatively chilly, close-to-winter weather for their efforts. We now understand that Nothomyrmecia succeeds at least in part because it is a cold-weather specialist. It is nimble enough to find and capture insects and other arthropod prey that are more chilled and less nimble.

At the climatic opposite extreme to Nothomyrmecia are the Cataglyphis ants of Eurasia and Africa, which thrive in hot weather on burning sand, and collect prey that are killed or immobilized by the extreme heat. A close parallel to Nothomyrmecia in climate specialization among ants in the North American temperate region is the cold-weather ant Prenolepis imparis. Its colonies are very active on milder days in the winter, forming lines from the nest out into hunting groups, but in the summer they retreat into deep, cool tunnels excavated for the purpose.

As Charles Darwin discovered during his month-long visit to the Galápagos in 1835, large, distant islands of ancient age are often rich relicts of endemic species—plants and animals of a kind found nowhere else. There is romance of a kind, and potentially science at its best, waiting for biological specialists to discover and for the time to study them. So it was in 1969, when William L. Brown was the first ant expert to visit the remote Mascarene archipelago, including the island of Mauritius, home of the long-extinct dodo.

Would there be ant equivalents of the dodo among the Mascarene Islands, and particularly in the surviving natural environments of Mauritius?

The prime locality to search for the last remnants of this island’s endangered fauna is Le Pouce, an elongated massif with a topside plateau covered with low, gnarled native forest. After one only partially successful trip to the plateau, Brown decided on a second effort, which he later described as follows:

On the first of April, though I was scheduled to leave on an evening flight to Bombay, I tried Le Pouce again. A telephone call to Mr. J. Vinson, who had collected some material, convinced me that the main path on the Le Pouce plateau should not be avoided. I arrived there in the afternoon; the day was heavily overcast, threatening rain on the peaks, and it took me about an hour to walk up to the plateau. Whereas the sunny Sunday in the scrub shade had yielded almost no ants foraging, I now found foragers on foliage and on the hard-packed earth of the trail every few meters of the way. These were mostly Camponotus aurosus and Pristomyrmex spp. (= Dodous), native Mauritian species. Before long, on the trunk of a small tree by the path, I found a sparse trail of bright red ants climbing the bark. Closer examination revealed these to be predominantly the ectatommine I had collected on the previous Sunday, but interspersed with these were workers of Pristomyrmex bispinosus which, with their gasters partly curled under, looked remarkably like the ectatommines. It is hard to avoid the impression that some kind of mimicry involves these two species in this habitat. The ectatommines ascending the trunk nearly all carried in their mandibles whitish spherical objects that proved eventually to be arthropod eggs—probably spider eggs. I climbed the tree which was only about 5 meters high, and soon found the nest about 3 meters up. Where two of the gnarled branches crossed, a thick pad of lichens surrounded the place where they touched. Forcing the branches apart, I found a rotted-out pocket, evidently caused by their rubbing together in high winds. The cavity extended downward several centimeters into one of the branches, and it was full of the ectatommine ants with brood and many of the round white arthropod eggs; I estimate that I removed or saw at least 200 workers, and there may have been more.

Afterward, in an incident about which he did not write, Brown attempted to climb the small peak at the end of the plateau. Lightning struck 20 feet upslope, then heavy rain turned the ground into slippery mud. Brown fell and slid down the slope toward the brink of a high cliff. Hanging on to a small bush for a few minutes, he finally regained his purchase and worked his way back down to the trail and then to Port Louis.

The bright red ant turned out to be an undescribed Proceratium (P. avium), notable for its aboveground foraging for eggs, in marked contrast to the other, wholly subterranean members of the genus. Also, the enlargement of its one-faceted eyes suggests that avium emerged as an aboveground forager late in evolution, after the arrival of its ancestral stock on the remote island of Mauritius.

Bill Brown’s Mauritius ants, secured at the risk of his life, did not happen as a consequence of his targeting species of great antiquity. He traveled to the Mascarenes as an effort of pure exploration. What species of any kind, he asked, might be found?

The planet contains many other places of which the question may be asked by new generations of scientists, “What species of any kind might be found?”

A worker of Nothomyrmecia macrops, the Australian winter ant, which has been judged one of the most primitive ant species in the world. (Drawing by Kristen Orr.)