Chapter 11

Saving for College with Qualified U.S. Savings Bonds

In This Chapter

Figuring out which savings bonds qualify

Figuring out which savings bonds qualify

Discovering who’s eligible to save for college with savings bonds

Discovering who’s eligible to save for college with savings bonds

Paying for qualified educational expenses tax-free

Paying for qualified educational expenses tax-free

Purchasing and redeeming savings bonds

Purchasing and redeeming savings bonds

When members of Congress first dabbled with the idea of giving taxpayers incentives to save for college expenses, they didn’t roll out some fancy new plan or program, creating unnecessary complexity (they saved that for much later). And they also didn’t want to target the upper and upper-middle classes — they figured that those folks could pay for college expenses on their own. Instead, they looked to the solidly middle class, checked out the ever dropping savings rate, and built a new savings perk into an already existing savings option that people viewed as generally stodgy and unexciting: U.S. Savings Bonds.

U.S. Savings Bonds, specifically Series EE and the new Series I bonds, remain a stodgy and unexciting way to save. Which is why you may be surprised to find out that these small pieces of the national debt can often provide you with a great tax-saving option: When you use them to pay for qualified higher education expenses, you’re allowed to exclude from your taxable income all the interest you’ve earned on them over the years.

In this chapter, you take a fresh look at Series EE and Series I savings bonds and find out how they work, what they do, and how you can use them to save for all or a part of what you later will need to pay to cover your own, your spouse’s, or your child’s postsecondary educational expenses. You see how easy savings bonds are to buy, own, and redeem. You find out how interest rates are set and when interest is posted. And finally, you discover what to do when you redeem your bonds and use them to pay for college expenses.

Choosing Savings Bonds that Work

You may use any sort of U.S. Treasury obligation, from bonds, notes, and T-bills all the way to Series EE, Series H, and Series I savings bonds to pay for anything at all that you’d like, including college expenses. Every one of them is backed by the “full faith and credit” of the U. S. Treasury, and all of them represent safe, if somewhat uninspired, investments. You may use only two of them, though, Series EE and Series I savings bonds, to pay postsecondary education costs without having to pay federal income tax on the interest that you earn on your investment.

Series EE savings bonds

Series EE savings bonds are your old-fashioned, garden-variety sort of savings bond, the kind your grandmother used to give you for high school graduation or your wedding. If you meet all the requirements (see the “Rating the Usefulness of Saving Bonds for You” section later in the chapter), you may redeem them to pay for some college expenses without paying any federal income tax. In addition, they have the following features:

They’re issued at 50 percent of their face value. This means that a $100 bond costs you $50 to purchase.

They’re issued at 50 percent of their face value. This means that a $100 bond costs you $50 to purchase.

They’re offered in a variety of face amounts. They range in face value from $50 to $10,000.

They’re offered in a variety of face amounts. They range in face value from $50 to $10,000.

They’re guaranteed to reach their face value within 20 years. But they’ll continue to earn interest after they’ve reached that value until the bond is 30 years old.

They’re guaranteed to reach their face value within 20 years. But they’ll continue to earn interest after they’ve reached that value until the bond is 30 years old.

Their issue date is always the first of a month, no matter what day of the month you actually purchase the bond.

Their issue date is always the first of a month, no matter what day of the month you actually purchase the bond.

Interest is compounded semiannually and is paid only when the bond is redeemed. Interest rates are announced every May 1 and November 1 for the following 6-month period.

Interest is compounded semiannually and is paid only when the bond is redeemed. Interest rates are announced every May 1 and November 1 for the following 6-month period.

You may cash the bond at any time, provided it is at least 6 months after the issue date for a bond issued prior to February 1, 2003, or 12 months after the issue date for a bond issued after that date. If you cash a bond that you purchased after April 30, 1997, that you’ve owned for less then 5 years, you’ll also forfeit 3 months’ worth of interest. For example, if you hold a bond for 2 years and then cash it in, you’ll only receive interest for 21 months.

You may cash the bond at any time, provided it is at least 6 months after the issue date for a bond issued prior to February 1, 2003, or 12 months after the issue date for a bond issued after that date. If you cash a bond that you purchased after April 30, 1997, that you’ve owned for less then 5 years, you’ll also forfeit 3 months’ worth of interest. For example, if you hold a bond for 2 years and then cash it in, you’ll only receive interest for 21 months.

You may exchange a Series EE bond for a Series HH bond at any time. You can defer the income tax on the accumulated interest in the EE until the HH reaches maturity. This can extend your tax deferral up to 20 years.

You may exchange a Series EE bond for a Series HH bond at any time. You can defer the income tax on the accumulated interest in the EE until the HH reaches maturity. This can extend your tax deferral up to 20 years.

You may not purchase more than $30,000 face value ($15,000 cash value) of Series EE bonds in any calendar year.

You may not purchase more than $30,000 face value ($15,000 cash value) of Series EE bonds in any calendar year.

.jpg)

Series I savings bonds

Like Series EE bonds, Series I bonds may be used to pay some college fees if you can meet all the requirements (see the “Rating the Usefulness of Saving Bonds for You” section later in the chapter). Although they’re very similar to Series EE bonds in many ways, following the same rules regarding issue dates, how long you must hold a bond before you can cash it in, and how much interest you forfeit if you redeem a bond that you’ve owned for less than five years (three months), Series I savings bonds have the following differences:

Series I savings bonds are offered at face value. You may purchase them in denominations ranging from $50 to $10,000, but you have to cough up the full face amount when you buy the bond.

Series I savings bonds are offered at face value. You may purchase them in denominations ranging from $50 to $10,000, but you have to cough up the full face amount when you buy the bond.

They have no guaranteed return. Because you already paid $100 for that $100 face bond, the government doesn’t need to guarantee that you’ll receive $100 when you redeem the bond. What you will receive on redemption, though, is your original $100 investment plus the interest on that $100, calculated monthly and compounded semiannually, making the value of your bond grow and grow.

They have no guaranteed return. Because you already paid $100 for that $100 face bond, the government doesn’t need to guarantee that you’ll receive $100 when you redeem the bond. What you will receive on redemption, though, is your original $100 investment plus the interest on that $100, calculated monthly and compounded semiannually, making the value of your bond grow and grow.

You may not purchase more than $30,000 face value ($30,000 cash value) of Series I bonds in any calendar year.

You may not purchase more than $30,000 face value ($30,000 cash value) of Series I bonds in any calendar year.

The only thing you may exchange this bond for is cash. You can’t turn it into a Series EE or a Series HH bond.

The only thing you may exchange this bond for is cash. You can’t turn it into a Series EE or a Series HH bond.

Determining Who’s Eligible

There are no limitations on who may own a U.S. Savings Bond. These bonds existed long before Congress ever attempted to mold them into a preferred college savings option, and they’re far too imbedded in the savings psyches of a wide group of people for Congress ever to try to limit who can own them or how many may be owned.

On the other hand, when the regulations surrounding the use of these bonds as a tax-free way to pay for college were created, Congress was in a position to place limitations on who could use this method of saving and how much could be saved. If you’ve already read the chapters on Section 529 plans (Part II) and/or Coverdell Education Savings Accounts (Part III), you may find the restrictions surrounding the use of U.S. Savings Bonds to be particularly burdensome. Keep in mind, though, that without this first foray into the world of tax-exempt saving for college, Section 529 plans and Coverdell accounts probably wouldn’t exist today.

Age requirements

To save for college tax-free using either Series EE or Series I savings bonds, the owner needs to be at least 24 years old on the first day of the month when the bond is issued. There are no exceptions here. If you turn 24 on June 18, 2003, and you purchase a bond on June 19, 2003 (so you really and truly are 24 years old), the issue date is regarded as June 1, 2003, when you weren’t yet 24 years old. Tough luck, but you’ll have to pay tax on the interest that you earn on that particular bond. You should have waited until July.

Ownership

To exclude the income earned from a Series EE or Series I savings bond from your income, you must be the owner of the bond. You may not buy bonds as a gift for someone (perhaps you’re 24, and the person you want to buy for is not) and retain the tax benefit for yourself. Additionally, if you do buy bonds as gifts for your children or grandchildren who are under 24 at the time the bonds are purchased, they’ll have to pay any income tax that is due on the earnings, regardless of how old you were when you purchased the bonds.

Relationship test

Yourself: Provided the bonds were issued after your 24th birthday, you can use them for your own qualified educational expenses and not pay any income tax at all.

Yourself: Provided the bonds were issued after your 24th birthday, you can use them for your own qualified educational expenses and not pay any income tax at all.

Your spouse: A spouse qualifies provided that you’re filing a joint income tax return.

Your spouse: A spouse qualifies provided that you’re filing a joint income tax return.

Your children: Children are eligible as long as you still claim them as dependents on your income tax return. After they claim their own personal exemption, you’re out of luck.

Your children: Children are eligible as long as you still claim them as dependents on your income tax return. After they claim their own personal exemption, you’re out of luck.

Annual income

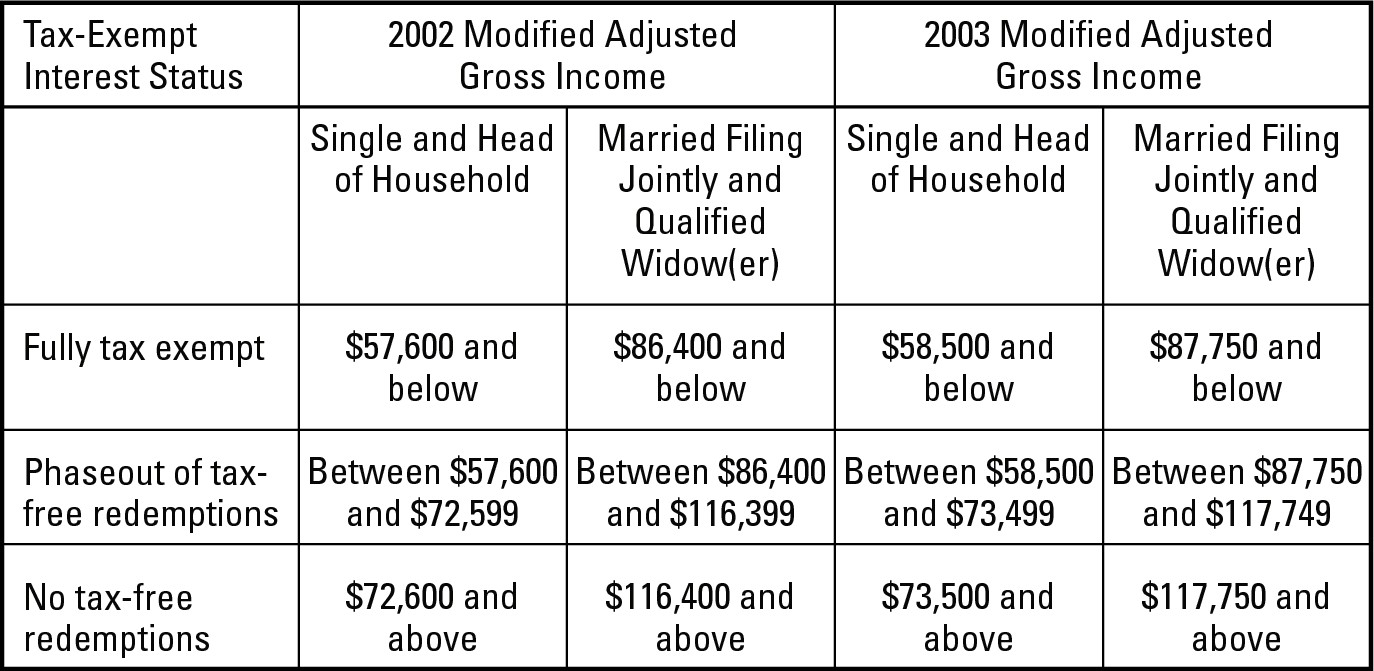

Congress always intended that this particular tax break be reserved for those people who, despite limited income, were doing their best to see their children through college. Because of that, it seriously restricted who could participate in these tax-free redemptions by putting very strict income requirements in place. Fortunately, these amounts are adjusted annually for inflation. Unfortunately, the amounts were never overly generous to begin with, and they don’t improve much even with the inflation adjustment. Figure 11-1 shows the 2002 and 2003 limitations for both married and single taxpayers.

|

Figure 11-1: 2002 and 2003 income phaseouts for tax-free Series EE and Series I savings bond redemptions. |

|

If you’re planning on using savings bonds to pay for college, you need to know what expenses are qualified for the purpose of redeeming these bonds tax-free. Remember that although U.S. Savings Bonds are safe and reliable, they’re not particularly exciting when you look at how much money you can make with them. They become players when you can make that money not pay any income tax.

Tuition and fees to an eligible postsecondary educational institution: The school’s ability to participate in federal financial aid programs administered by the U.S. Department of Education is the test here. Although you’re not required to provide anyone with proof of what you include as qualified educational expenses, be sure that you can substantiate your claims. If the IRS comes calling and asks for your records, be certain that you can gently place those canceled checks or receipted tuition bills under the agent’s nose.

Tuition and fees to an eligible postsecondary educational institution: The school’s ability to participate in federal financial aid programs administered by the U.S. Department of Education is the test here. Although you’re not required to provide anyone with proof of what you include as qualified educational expenses, be sure that you can substantiate your claims. If the IRS comes calling and asks for your records, be certain that you can gently place those canceled checks or receipted tuition bills under the agent’s nose.

Payments into Section 529 plans or Coverdell Education Savings Accounts: You may already have purchased one or two or more Series EE or Series I savings bonds with the idea of using them for educational expenses, but you’re watching your salary rise, and think that you may soon be earning more than is allowed in order to take advantage of tax-free redemptions (see the “Annual income” section later in this chapter). Before this window closes, you may want to redeem those bonds, and invest all of your redemption funds into a Section 529 plan, a Coverdell account, or both.

Payments into Section 529 plans or Coverdell Education Savings Accounts: You may already have purchased one or two or more Series EE or Series I savings bonds with the idea of using them for educational expenses, but you’re watching your salary rise, and think that you may soon be earning more than is allowed in order to take advantage of tax-free redemptions (see the “Annual income” section later in this chapter). Before this window closes, you may want to redeem those bonds, and invest all of your redemption funds into a Section 529 plan, a Coverdell account, or both.

You can’t pay for room and board, books, supplies, and all the other great things that you’re allowed to pay for by using distributions from Section 529 plans or from Coverdell accounts with tax-free savings bond redemptions.

.jpg)

To further complicate matters, if you’re planning on taking the Hope Credit or the Lifetime Learning Credit (see Chapter 16), you must pay for the qualified expenses that you assign to these credits with money you’ve paid tax on. If you’re paying for expenses using Series EE or Series I savings bonds, you have to pay the income tax on the interest to be eligible for the credits.

Buying and Redeeming Savings Bonds

You may have decided that Series EE and/or Series I savings bonds sound good to you. You want to start implementing a savings program using them, but you’re not quite sure how you go about buying them. Actually, they’re quite easy to buy through a variety of means, and they require a lot less paperwork than Section 529 plans or Coverdell accounts. And, after you actually buy a bond, you don’t need to do anything further until you redeem it. You don’t have to read any statements or make any investment decisions.

At your local bank.

At your local bank.

Through payroll deduction plans at your workplace.

Through payroll deduction plans at your workplace.

From your local Federal Reserve Bank (in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Kansas City, Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, San Francisco, and St. Louis).

From your local Federal Reserve Bank (in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Kansas City, Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, San Francisco, and St. Louis).

Directly from the Bureau of the Public Debt through the mail or over the Internet. You can use the EasySaver Plan (which makes automatic transfers from your bank) or Savings Bonds Direct (which uses a major credit card).

Directly from the Bureau of the Public Debt through the mail or over the Internet. You can use the EasySaver Plan (which makes automatic transfers from your bank) or Savings Bonds Direct (which uses a major credit card).

However you buy your bonds, you must provide your name, address, and Social Security number to complete the transaction. And that’s it. If you buy a bond as a gift for someone else, you need to provide their name, address, and Social Security number.

You may redeem your bonds at any institution where you can buy them; you don’t need to redeem them at the same place where you first purchased them. When you make that redemption, you receive a Form 1099-INT for the interest you haven’t reported. If you use the total amount of the proceeds (the amount you first paid to buy the bond plus all the interest) to pay for qualified expenses, no problem. You’ll exclude that interest by using Form 8815 on your income tax return. Form 8815 also walks you through the calculations if you fall into the income phaseout gray area or if you use only part of the bond proceeds to pay for qualified expenses.

Rating the Usefulness of Saving Bonds for You

On their face, U.S. Series EE and Series I savings bonds may not seem the swiftest way to stash a substantial amount of money away for college. However, they have a lot of good points, especially for the small investor, including the following:

Your money is safe with Uncle Sam. No ifs, ands, or buts about it — U.S. Treasury issues are the safest investment around. If you’re worried about the ups and downs of the stock market or you just watched yet another bank close its doors, that safety may appeal to you.

Your money is safe with Uncle Sam. No ifs, ands, or buts about it — U.S. Treasury issues are the safest investment around. If you’re worried about the ups and downs of the stock market or you just watched yet another bank close its doors, that safety may appeal to you.

You may save in very small amounts. As in any investment scheme, you must pay a minimum amount to start playing. With U.S. Series EE savings bonds, that amount is a princely $25. If you’re concerned about paying the rent but still want to be putting something aside, this may be just the ticket for you.

You may save in very small amounts. As in any investment scheme, you must pay a minimum amount to start playing. With U.S. Series EE savings bonds, that amount is a princely $25. If you’re concerned about paying the rent but still want to be putting something aside, this may be just the ticket for you.

You’ll never pay any initiation or annual fees to maintain a savings bond account. Even if your bonds exist only on the records of the Bureau of Public Debt (which cuts down on the chances that you may lose the little slips of cardboard that pass for savings bonds these days), it doesn’t charge you for the privilege of looking after your money.

You’ll never pay any initiation or annual fees to maintain a savings bond account. Even if your bonds exist only on the records of the Bureau of Public Debt (which cuts down on the chances that you may lose the little slips of cardboard that pass for savings bonds these days), it doesn’t charge you for the privilege of looking after your money.

Interest rates are competitive and actually exceed most bank and money market interest rates, and you won’t ever pay any state income tax on your interest. The interest rates for Series EE bonds are calculated at between 85 and 90 percent of the current five-year U.S. Treasury Note, depending on the issue date of the bond. For Series I bonds, the rate is calculated by adding a fixed rate of return to an inflation component that is calculated semi-annually.

Interest rates are competitive and actually exceed most bank and money market interest rates, and you won’t ever pay any state income tax on your interest. The interest rates for Series EE bonds are calculated at between 85 and 90 percent of the current five-year U.S. Treasury Note, depending on the issue date of the bond. For Series I bonds, the rate is calculated by adding a fixed rate of return to an inflation component that is calculated semi-annually.

If your student ends up not going to college or another eligible school, you don’t have to pay any penalty to get your money out. When you redeem your bonds, you’ll pay the federal income tax on the interest, but you don’t have a mandatory deadline for cashing in your bonds.

If your student ends up not going to college or another eligible school, you don’t have to pay any penalty to get your money out. When you redeem your bonds, you’ll pay the federal income tax on the interest, but you don’t have a mandatory deadline for cashing in your bonds.

On the flip side (and there’s always a flip side), you won’t ever get rich putting all your money into U.S. Savings Bonds. The interest rates are very low and will probably stay that way for quite some time. To add to that, interest is compounded only semiannually, which further lowers your potential earnings. If you’re looking to make a lot of money fast, Series EE and Series I savings bonds aren’t for you.

If, however, you’ve started saving early and have another college savings plan in place, savings bonds are a great addition.