Chapter 4

Sharpening Your Savings Techniques

In This Chapter

Budgeting your money, not pinching your pennies

Budgeting your money, not pinching your pennies

Seeing savings as a reward, not a punishment

Seeing savings as a reward, not a punishment

Freeing yourself from debt

Freeing yourself from debt

Starting to save at any age

Starting to save at any age

At some point early in your children’s lives, you need to calculate how much you think that you’ll need to see your children through school and figure out who’s going to be paying when the time comes. Essentially, you’re defining the size of the problem.

Now, your biggest concern is finding a solution. Because, as much as you realize you need to save money, you’re not saving money! You’re sure you have the will, the desire, and the need — you just seem to be lacking the cash. This chapter dissects your life and your spending habits (just a little bit). It shows you that adding more money to this equation isn’t the only way you can ever increase the amount of cash you save. Although finding additional money is always nice, you can use a variety of methods to carve some savings out of what you already have.

Focusing on the Family Budget

The mechanics of your family’s budget are fairly straightforward — you bring in a certain amount of money, through work, entitlement programs such as Social Security or other pensions, or investments. From that money, or income, you need to pay for the basic needs of your family — housing and utility costs, food, clothing, transportation, insurance, and so on — and for the frills your family has come to expect — cable television, vacations, and fancy gifts at birthdays and holidays.

While that sounds simple enough, you may find that your family’s needs and expectations slightly exceed your income. You may also want to save a significant piece of your income each month, but when the end of the month comes, you find that you’re a bit short. If you find yourself in either situation, thinking that saving money for college is impossible, put that pint of ice cream back in the freezer and check out my tips on how to dig for the dollars you need in your monthly budget to start saving for college.

Eliminating most of the fat

The first step in gaining control over your family’s finances is not to cut off the cable television or the Internet connection or take the family dog to the pound. You need to take a step back and look at the big picture — you need to know not only how much money you have coming in but also how much is going out and where that money is headed.

Making lists of where you are now

Before you can start making changes to your family’s finances, you need to understand what you have right now, at this moment. Sit down and make a list of your monthly income and, if your income tends to be seasonal at all, your yearly income (and then divide that by 12). List all your income, from every source. Don’t declare this account or that resource as off-limits. Every income item needs to be on the table (no, the IRS isn’t looking over your shoulder).

Your next list needs to be those payments that you absolutely, positively, need to make, including the following:

Rent or mortgage (plus necessary repairs)

Rent or mortgage (plus necessary repairs)

Food

Food

Utilities (not including cable)

Utilities (not including cable)

Insurance (life, disability, medical, homeowners/renters, and car)

Insurance (life, disability, medical, homeowners/renters, and car)

Car and other transportation costs

Car and other transportation costs

Student loan payments

Student loan payments

Taxes

Taxes

Charitable contributions

Charitable contributions

Annual clothing costs for your family

Annual clothing costs for your family

Once again, if amounts change seasonally, add up a year’s worth of bills and expenses and then divide by 12.

Third, you need to catalog so-called discretionary items — entertainment costs, travel, cable or satellite television, Internet access, gym memberships, private school tuitions, and so on. Depending on your family, this list can be quite extensive.

Finally, take a good look at how much you pay each month on outstanding consumer debt (plus the total amount you owe). Make sure you add your credit-card payments to your lists of expenditures, as well as any bank fees that you may pay on your checking account.

After you have all your lists prepared, you’ll be able to see where your money goes and how much of it you actually fribble away.

Carving away the truly wasteful

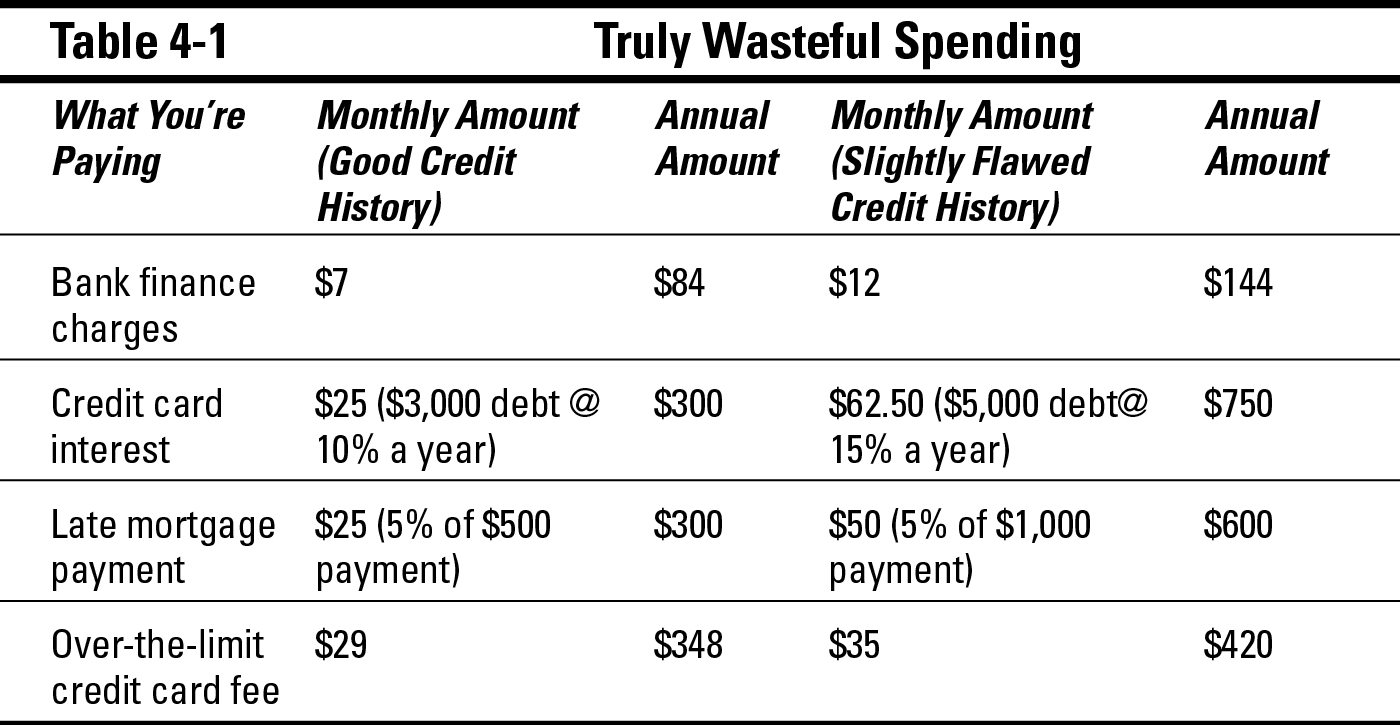

With your income and current spending patterns laid out in front of you, you probably won’t have any trouble spotting the expenditure items that are really, really wasteful. Right at the top of the list are bank and finance charges. You may consider these charges to be minimal, but adding those minimal costs up can be another story. Check out the following examples of potential fees you could face, depending on how you manage your money:

Minimum balance penalty: Some banks assess fees if your checking account carries a balance below the minimum for the month. For example, if my checking account balance drops below $750 in any month (even it’s $749), my bank hits me with a $7 per month fee.

Minimum balance penalty: Some banks assess fees if your checking account carries a balance below the minimum for the month. For example, if my checking account balance drops below $750 in any month (even it’s $749), my bank hits me with a $7 per month fee.

Insufficient funds penalty: I don’t know of any bank that doesn’t slap a fee of at least $20, if not more, on bounced checks.

Insufficient funds penalty: I don’t know of any bank that doesn’t slap a fee of at least $20, if not more, on bounced checks.

Credit card interest: Carrying a balance on your credit card can cost you between 10 and 20 percent (or more) per year for the loan of that money in interest alone.

Credit card interest: Carrying a balance on your credit card can cost you between 10 and 20 percent (or more) per year for the loan of that money in interest alone.

Over-limit fees: Most credit card companies charge a fee if you go over your credit limit — like a bounced check, I don’t know of any credit card that charges less than $20 each month for going over the credit limit.

Over-limit fees: Most credit card companies charge a fee if you go over your credit limit — like a bounced check, I don’t know of any credit card that charges less than $20 each month for going over the credit limit.

Late-payment fees: If your payment check doesn’t arrive on time, it’ll probably cost you at least $20 for the month. (Late payments also decrease credit-worthiness and increase the cost of later loans to you.)

Late-payment fees: If your payment check doesn’t arrive on time, it’ll probably cost you at least $20 for the month. (Late payments also decrease credit-worthiness and increase the cost of later loans to you.)

Table 4-1 paints a picture of how these fees can add up for a typical family.

Paying health club dues to a club you haven’t attended for over a year

Paying health club dues to a club you haven’t attended for over a year

Continuing a newspaper subscription that you just haven’t gotten around to canceling

Continuing a newspaper subscription that you just haven’t gotten around to canceling

Hitting the coffee shop for a cup o’ joe in the morning because you don’t get up early enough to make your own

Hitting the coffee shop for a cup o’ joe in the morning because you don’t get up early enough to make your own

Going out for dinner or lunch rather than eating at home

Going out for dinner or lunch rather than eating at home

Wasteful spending can be curbed if you take the time to assess your spending. I’m not advocating punishing your family by getting rid of a health club membership, but I am advocating ridding yourself of expenses that you don’t need or put to use. Add up what you waste each month. Start getting payments in on time, maintaining the minimum balance in your checking account, making coffee at home, or canceling memberships or subscriptions that you don’t use so that you can begin saving that money for college.

Reorganizing what’s left

If you’ve crossed off all of the wasteful spending, or if you had no wasteful spending to begin with, you can still lower your total expenses each month. Check out what’s left of your expenses and see whether you can take advantage of additional ways to save that I discuss in the following sections.

Lowering your debt

The biggest piece of most budgets is the amount folks pay to their mortgage company, their car finance company, and their credit card companies. Many people are surprised to find that they pay more than they need to in many of these areas. Check out the following ways to reduce your monthly debt:

Consider refinancing your house. Look at your current housing, car, and credit card payments. You may be able to consolidate all these loans into one mortgage, and leave your mortgage closing with one monthly payment that’s significantly less than the total of all debt payments you had been making. While this isn’t true in every case and is dependent on interest rate fluctuations and the current value of your house, it’s certainly worth an afternoon or evening of your time to investigate.

Consider refinancing your house. Look at your current housing, car, and credit card payments. You may be able to consolidate all these loans into one mortgage, and leave your mortgage closing with one monthly payment that’s significantly less than the total of all debt payments you had been making. While this isn’t true in every case and is dependent on interest rate fluctuations and the current value of your house, it’s certainly worth an afternoon or evening of your time to investigate.

Consolidate your student loans. If you’re currently paying off student loans, and you haven’t yet consolidated them, you may find that now is the time. Depending on the amount you owe and current interest rates, you may be able to significantly lower your monthly payment.

Consolidate your student loans. If you’re currently paying off student loans, and you haven’t yet consolidated them, you may find that now is the time. Depending on the amount you owe and current interest rates, you may be able to significantly lower your monthly payment.

Liquidate your assets. Another way to lower debt payments is to liquidate assets that you may have and pay down your debt. If, for example, you have shares of stock that aren’t increasing in value, it may be well worth it to sell the stock and pay off your credit cards.

Liquidate your assets. Another way to lower debt payments is to liquidate assets that you may have and pay down your debt. If, for example, you have shares of stock that aren’t increasing in value, it may be well worth it to sell the stock and pay off your credit cards.

Lower your credit card interest rate. If you can’t retire your credit card debt entirely, negotiate with your credit card companies for lower rates. You’ll need a history of timely payments; one late payment will muddy the water considerably — two or more, and they’ll probably just laugh. If your current company won’t negotiate, go shopping. Many banks are eager for your business, often with introductory rates as low as 0% for three, six, or nine months. Transfer your high-interest balance, and pay it off before the introductory rate expires.

Lower your credit card interest rate. If you can’t retire your credit card debt entirely, negotiate with your credit card companies for lower rates. You’ll need a history of timely payments; one late payment will muddy the water considerably — two or more, and they’ll probably just laugh. If your current company won’t negotiate, go shopping. Many banks are eager for your business, often with introductory rates as low as 0% for three, six, or nine months. Transfer your high-interest balance, and pay it off before the introductory rate expires.

Trade down when you trade in. Take a close look at your car and the size of your car payments. When getting a new vehicle, consider something less than a Mercedes even if the dealer says that you can afford it. He’s trying to put his own kids through college, but your responsibility extends only as far as your own offspring — not his.

Trade down when you trade in. Take a close look at your car and the size of your car payments. When getting a new vehicle, consider something less than a Mercedes even if the dealer says that you can afford it. He’s trying to put his own kids through college, but your responsibility extends only as far as your own offspring — not his.

Consider debt consolidation. If you’re really burdened by debt, and can’t find any reasonable way out (robbing a bank isn’t reasonable), making an appointment with a reputable credit counselor isn’t the worst idea. Counselors can often negotiate deals with your creditors that you won’t be able to get on your own, and through their services, you may be able to eliminate hundreds of dollars from monthly credit card and other loan bills. If you consider this option, remember that this may damage your credit-worthiness. Of course, it may also help: If you’re so deeply in debt that you need to consult with one of these services, you’re probably also missing payments, making late payments, and otherwise messing up your credit rating. In the long run, your creditors will likely be relieved to see you gaining some control over your finances.

Consider debt consolidation. If you’re really burdened by debt, and can’t find any reasonable way out (robbing a bank isn’t reasonable), making an appointment with a reputable credit counselor isn’t the worst idea. Counselors can often negotiate deals with your creditors that you won’t be able to get on your own, and through their services, you may be able to eliminate hundreds of dollars from monthly credit card and other loan bills. If you consider this option, remember that this may damage your credit-worthiness. Of course, it may also help: If you’re so deeply in debt that you need to consult with one of these services, you’re probably also missing payments, making late payments, and otherwise messing up your credit rating. In the long run, your creditors will likely be relieved to see you gaining some control over your finances.

Trimming other costs

Clearly, you need electricity, water, telephone service, heat, and so on. And, for most of you, these costs are not negotiable — the utility companies have cultivated a world of monopolies, and in most cases, no bargains are to be found as far as price per unit goes. However, you may be able to reduce costs within your own household, and these are well worth exploring.

Ask for a lower rate. Telephone and heating oil companies are highly competitive. Don’t hesitate to shop around, and ask your current company to meet, or beat, a competitor’s lower price.

Ask for a lower rate. Telephone and heating oil companies are highly competitive. Don’t hesitate to shop around, and ask your current company to meet, or beat, a competitor’s lower price.

Pay for only what you use. Don’t pay for more cable and/or satellite service than you need or can use. Cut back to a place that still provides the programming that you want but doesn’t give you a whole lot of extras that you rarely use.

Pay for only what you use. Don’t pay for more cable and/or satellite service than you need or can use. Cut back to a place that still provides the programming that you want but doesn’t give you a whole lot of extras that you rarely use.

Practice energy conservation. Upgrade your house with energy- and water-efficient appliances and improvements. Many of these have small upfront costs (energy-efficient light bulbs and low-flow toilets, for example) but pay off in huge savings over their lifetimes.

Practice energy conservation. Upgrade your house with energy- and water-efficient appliances and improvements. Many of these have small upfront costs (energy-efficient light bulbs and low-flow toilets, for example) but pay off in huge savings over their lifetimes.

Comparison-shop for insurance. Seek out the most competitive price for all your insurance needs — life, disability, homeowners/renters, car, and medical (if you pay for your own.) Many folks can trade a costly whole-life policy for a much less expensive term-life policy. Your life insurance coverage can remain the same for a fraction of the cost.

Comparison-shop for insurance. Seek out the most competitive price for all your insurance needs — life, disability, homeowners/renters, car, and medical (if you pay for your own.) Many folks can trade a costly whole-life policy for a much less expensive term-life policy. Your life insurance coverage can remain the same for a fraction of the cost.

Trim the grocery bill. You can slash your grocery bill by using coupons and store affinity cards and by shopping on sale. Also, don’t forget that house brands are almost always less expensive than the national brands, and for many items, the quality remains the same. Just because you’ve always used a certain brand doesn’t mean you have to continue to use it. The manufacturer won’t punish you for disloyalty.

Trim the grocery bill. You can slash your grocery bill by using coupons and store affinity cards and by shopping on sale. Also, don’t forget that house brands are almost always less expensive than the national brands, and for many items, the quality remains the same. Just because you’ve always used a certain brand doesn’t mean you have to continue to use it. The manufacturer won’t punish you for disloyalty.

Changing Your Perspective — Watching Your Savings Grow

Saving for any purpose, whether for college, retirement, a new home, or that dream vacation of a lifetime, isn’t a punishment, nor does it need to be a deferral of pleasure. Some people (and you all know someone like this) squeeze every penny until it squeals and never seem to have any fun. Who can forget Ebenezer Scrooge, after all? He began to live only after he stopped clutching his money quite so tightly. And he is, of course, the epitome of the saver — the miser.

Well, he’s a fictional character, and plenty of savers out there still know how to have a good time. And maybe they even have a better time, because at the end of the evening, they know they have the money to pay the bill.

Paying yourself first

That money needs to be physically segregated from the rest of your income (so you’re not tempted to dip into it, even a little, for that extra something you’ve been wanting to buy). Only after you’ve subtracted it and put it elsewhere should you figure out how much money you have available for all your other expenses, which need to fit into this smaller amount. If, after putting aside your savings amount, you can’t pay the rest of your monthly bills, you need to change something — find a cheaper mortgage, eat out less frequently, or buy fewer books. The choice is yours. The only item that isn’t on the table for negotiation is your savings amount.

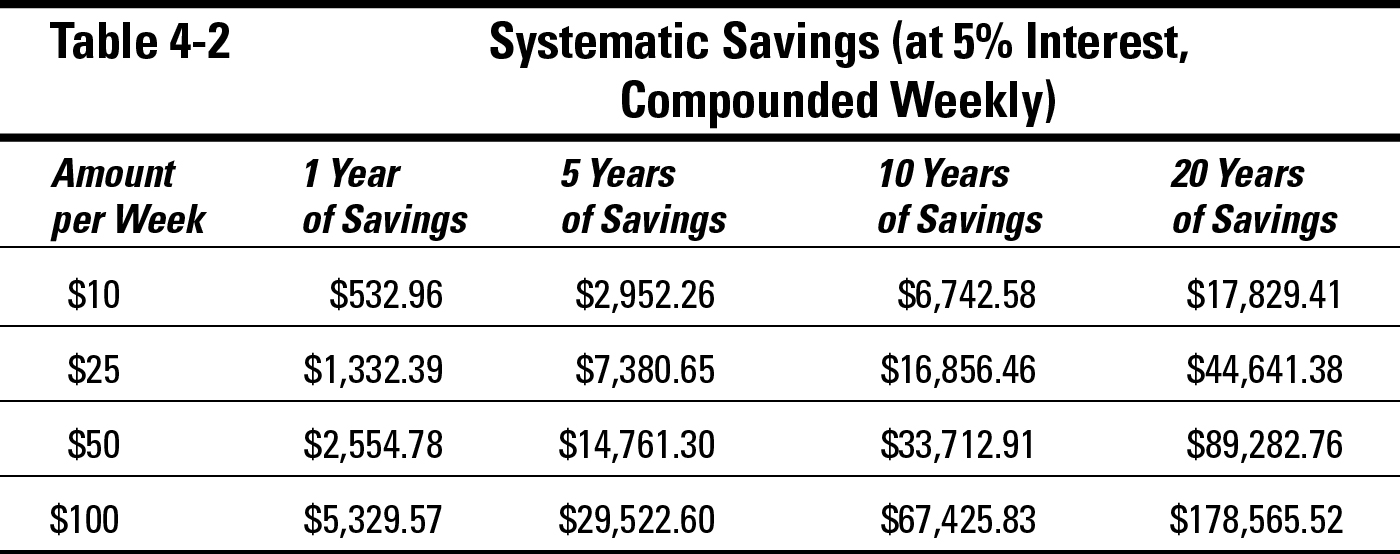

Systematically saving

You can successfully save if you put the same amount of money into some sort of savings account each and every week or month (depending on when your income is paid to you). Even if the periodic amounts may seem small to you, Table 4-2 illustrates how those savings can add up to considerable nest eggs at the end of one, five, ten, or twenty years.

Earmarking certain pieces of income for savings

Most people not only receive their normal income, paid at regular intervals, but they also have periodic injections of additional cash, whether it’s in the form of overtime wages, significant salary increases, holiday bonuses, gifts and/or inheritances, or even income tax refunds. (I can’t begin to tell you the number of times people have told me that they use additional withholdings on their pay as a way to save money.)

If you’ve been doing your job and dissecting your budget, you’ve probably already figured out how to live comfortably on what you earn on a regular basis, and you’re also, hopefully, now saving systematically and regularly.

Ah, but I can see ideas of a vacation, a new piece of jewelry, or redoing the kitchen dancing through your head. Obviously, if your household budget hasn’t included money for some glaring need (perhaps your roof is leaking) and you’ve just been waiting for some extra cash to pay for that project, you can divert at least some of that money for that purpose. But if you’ve managed to pare your spending to a place where you’re managing beautifully with what you have, take a big chunk of that extra money and sock it into your savings plans. What’s out of sight is also out of mind, and these additional funds may be just the ticket to beef up a somewhat anemic college savings or retirement account.

Educating yourself about investing

There can be no question about it: The world of investing can be a scary place, and the days when stockbrokers did your buying and selling have mostly gone the way of record albums and eight-track cassettes. Investing is now a do-it-yourself operation that can present many pitfalls for the unwary. Before you even think about sticking your big toe in the investing pool, you need to make sure you have a handle on the following.

Know what you’re buying

Your success with any investment rests squarely on your understanding of what you’re buying. Know what you’re paying for, whether it’s an individual stock or bond, a mutual fund, or even a certificate of deposit. You wouldn’t purchase an orange without first making sure it wasn’t rotten; don’t assume that every security being sold and touted by the so-called experts is as solid as Fort Knox. Do your own research and make your own decisions.

Understand and be able to live with risk

After you move beyond bank savings accounts, certificates of deposit, and mutual fund money market accounts, you enter the world of ever increasing risk. Whether you invest in individual securities or in mutual funds (which are nothing more than pools of individual securities), the price of those securities can rise (which you hope for) and also fall (which you dread).

Risk is inherent in the investment world. Whether you buy small pieces of companies (stocks, or equities) or lend companies and/or governments money (bonds, or debt instruments), your money is only as secure as the company or companies you’ve tied it to, as well as the general economic conditions both in the United States and around the world.

In other words, if you can’t even contemplate that your savings may be worth less next week, or even next year, than they are today, you may want to reconsider plunging your money into a junk bond fund. (Junk bonds are loans to companies that Wall Street has serious doubts about, so they’re considered risky.) Instead, you may want to consider a mutual fund that purchases nothing but U.S. Treasury bonds and notes (very, very safe).

Balance risk and expectations against future monetary needs

Not every great investment is a great investment for you. If you want to gamble on which company will be the next Microsoft or IBM, you need to have the luxury of time to allow that company to develop and grow. You may need to be patient; many start-up companies struggle initially, and the big payoffs, if they do develop, develop over time.

If you’re going to need to make that next tuition payment in the not-so-distant future (within the next five years), you may want to temper your level of risk, keeping a larger portion of your savings in cash and cash equivalents such as money market funds or certificates of deposit. I’m not saying that you can’t invest your teenager’s college savings funds in Wonder Widget, Inc.; you may want to only invest a small portion of those savings in it, and keep the majority of your money invested in less risky ventures.

Identify the cost

Just because you invest directly with a mutual fund company or through an Internet brokerage doesn’t mean that you’re going to avoid paying anything for the privilege of investing your money. Face it: People aren’t in this business for their health; they’re in it to make money. And they make a lot of it. And as far as purchasing individual securities, the cost of each transaction is usually right there on your confirmation slip.

Still, identifying exactly what a mutual fund costs you may be difficult because the management costs may be buried deep inside the prospectus. Search for it. A company may charge its fee based on a percentage of the value of the assets within a fund, or it may charge a percentage of income collected. Know how the fees in your accounts are calculated, and then factor that into total return for that fund.

Read the fine print about total returns

Every mutual fund company offers literature about how well its fund has performed against other similar funds and about the percentage of increase (or decrease, but those numbers tend to be in much smaller print) the fund has realized over time. The literature probably also touts the expertise of the fund manager (who chooses what to buy and what to sell within the fund).

Taking advantage of giveaways

You get something for nothing very few times in life, and money-back offers from credit cards and from retailers may or may not qualify as one of those times for you. Still, if you can take advantage of an offer without spending any additional money to do so, well, you would be foolish not to.

Credit card offers

Many credit cards are now offering a rebate equaling 1 percent of your total purchases towards a Section 529 plan (see Chapters 5 through 8) for yourself or your child. This plan may be in addition to, or instead of, other incentives that credit cards often offer, such as air miles, travel insurance, rental car insurance, and double warranties.

.jpg)

On the other hand, if you use a credit card anyway, you may want to investigate changing card companies to avail yourself of the offer. Doing so won’t put your child through school; however, every dollar that someone else puts into your savings plan is one less dollar that you need to find.

Upromise and BabyMint

Granted, these are all small amounts by themselves, but just as your small weekly deposits of savings add up over time, so do these. Depending on how many of the associated stores and products you use and how much you spend, your savings here could be substantial. You can find out all the details on the companies’ Web sites at www.upromise.com and www.babymint.com .

Dealing with Debt

Your debt probably hinders your plans to save money for college the most. You may find it difficult to justify putting money into a college savings account when you feel swamped by debts that need to be paid, and you may feel like you need to pay off all of your debts before you begin saving for your child’s college education. Fortunately for you, you don’t need to eliminate all debt before you begin to save. To show you how to save for college while drowning in red ink, discover the difference between good debt and bad debt and begin saving right now, regardless of your debt situation.

Understanding good debt and bad debt

The good news: Some types of debt are good, are factored into your monthly budget, and shouldn’t hinder you from saving for college. The bad news: Some types of debt are bad, should be paid off as quickly as possible, and hinder you from saving for college.

Clearly, you’re not planning on paying off your entire mortgage before you start saving for college, at least if you intend for your children to begin college before their hair turns gray. And you probably feel the same about your car payment, which is factored into your budget as a transportation cost, and any student loans that you may still have outstanding.

Even after you finish paying off the loan amounts for your house, your vehicle, and your education, those items should still have value to you. And from a credit-worthiness standpoint, since most credit rating companies expect you to have some form of this debt, the fact that you have these sorts of loans actually makes you more attractive as a potential borrower than having no loans at all (provided that you make your payments on time). This is good debt: debt that you plan for, budget for, and manage appropriately.

On the other hand, your credit cards (if you carry unpaid balances from month-to-month), your rent-to-own accounts, your layaway accounts, in fact, all of your so-called consumer debts are considered bad debt, and you should reduce or completely eliminate them if possible (see the section “Eliminating most of the fat,” earlier in this chapter, for ways to reduce and/or eliminate your debt). Consumer debt is money that you have borrowed to purchase something that is either a consumable (like groceries) or something that has a very limited life (last year’s clothes, perhaps, that your teenager won’t wear this year because they’re no longer fashionable). Basically, after you buy things in these categories, they cease to have any monetary value.

Now, I’m not saying that you shouldn’t buy food or clothing, or even that new television set. You do need to eat, after all, and watching television is still a relatively cheap form of entertainment. What you shouldn’t be doing, though, is borrowing money to satisfy these needs. And that is exactly what you do when you carry balances on your credit cards. You’re not only paying interest on last night’s dinner, but you also may still be paying for last year’s holiday gifts and your wedding dress from ten years ago.

.jpg)

Saving while in debt

Being in debt doesn’t preclude you from saving money for college. Sure, it makes doing so more difficult, but the following strategies can make saving for college, while paying down debt, more manageable.

Understanding the difference between needs and wants:

Needs fulfill a necessary function ably, but wants add other elements, at a price. For instance, you need a new television. The television you need is the one tucked away on the bottom shelf: 27 inches, color, and with a remote. But the one you want is on center display: It has picture-in-picture, surround sound, and who cares how many inches it is — it’s as big as the wall you plan to put it on! However, the one you want also costs much more than the one you actually need. Buying the one you need can make you just as happy, can fulfill the need for a television, and can ensure that you don’t break the bank or borrow money for it (like using your credit card) and have to pay it off in installments.

Understanding the difference between needs and wants:

Needs fulfill a necessary function ably, but wants add other elements, at a price. For instance, you need a new television. The television you need is the one tucked away on the bottom shelf: 27 inches, color, and with a remote. But the one you want is on center display: It has picture-in-picture, surround sound, and who cares how many inches it is — it’s as big as the wall you plan to put it on! However, the one you want also costs much more than the one you actually need. Buying the one you need can make you just as happy, can fulfill the need for a television, and can ensure that you don’t break the bank or borrow money for it (like using your credit card) and have to pay it off in installments.

As you slice away at your consumer debt and hopefully finally retire it, nurture the habit of looking at every potential purchase and expenditure from a need-versus-want perspective. Although denying yourself everything that you want may, in the end, be self-defeating and make you miserable (you’re not a monk, after all, and never took a vow of poverty), constant self-indulgence will prove equally disastrous.

Learning to defer gratification until you can afford it: No matter how badly you want that new television (whether the stripped down or deluxe version), don’t buy it until you’ve saved enough to pay for it. Most folks see a television as a necessity, but doing without for a period of time won’t kill you, and you may actually use the extra time you have to rediscover old hobbies, visit with friends, or otherwise pleasurably spend time. When the time comes to plop your hard-saved cash down on the store counter, you’re likely going to be more pleased with the less expensive TV than you would be with the bells-and-whistles model that you paid for with your charged-to-the-max piece of plastic.

Learning to defer gratification until you can afford it: No matter how badly you want that new television (whether the stripped down or deluxe version), don’t buy it until you’ve saved enough to pay for it. Most folks see a television as a necessity, but doing without for a period of time won’t kill you, and you may actually use the extra time you have to rediscover old hobbies, visit with friends, or otherwise pleasurably spend time. When the time comes to plop your hard-saved cash down on the store counter, you’re likely going to be more pleased with the less expensive TV than you would be with the bells-and-whistles model that you paid for with your charged-to-the-max piece of plastic.

Using credit as a tool, not a weapon: Consumer credit is not, by definition, a bad thing, and used properly, it can be a valuable tool. Paying for purchases using credit cards negates the need to carry large amounts of cash, allows you to pass unmolested through the checkout line at the grocery store (I’m not keen on giving out all of my personal information to someone I’ve never met), and at the end of the month or the year, you get an easy way to track your spending habits. Use it improperly, though, and it becomes a weapon that destroys your finances and demolishes good intentions. Be responsible: If you can’t pay your credit bill in full every month, destroy your cards and use cash instead. Budgeting cash will allow you to insert a line-item for savings.

Using credit as a tool, not a weapon: Consumer credit is not, by definition, a bad thing, and used properly, it can be a valuable tool. Paying for purchases using credit cards negates the need to carry large amounts of cash, allows you to pass unmolested through the checkout line at the grocery store (I’m not keen on giving out all of my personal information to someone I’ve never met), and at the end of the month or the year, you get an easy way to track your spending habits. Use it improperly, though, and it becomes a weapon that destroys your finances and demolishes good intentions. Be responsible: If you can’t pay your credit bill in full every month, destroy your cards and use cash instead. Budgeting cash will allow you to insert a line-item for savings.

Saving Throughout the Ages

Saving money for college, beginning the instant you know you have a child on the way, is certainly the most effective approach. However, if you couldn’t or didn’t save money for your child’s education back then, you may be behind in the savings game.

Beginning at birth

Saving for future events in your child’s life should begin no later than the day he or she is born, but you shouldn’t be the only one putting money away for that purpose. Your child eventually can help fund his college accounts, too. Use the occasion of your child’s birth to open up one or more college savings plans and an account in your child’s name, into which you can deposit any gifts he or she receives at birth. You can add birthday gifts and other such sums to it regularly, until your child is old enough to begin making his or her own deposits. There’s no better way to show your child the benefits of saving than to have a ready-made example with his or her name on it.

.jpg)

Getting in gear during the teen years

If you begin your child’s college savings accounts at birth, by the time he or she is a teenager, you should have a tidy sum inside those accounts. Still, you’re edging ever closer to that magic matriculation date, and some of your investments may not have been gold-plated. It’s never too early to start saving, but it’s also never too late: It’s time to start superfunding your Section 529 plan, if you can.

Regarding the money you have managed to save, it doesn’t matter if your investments have done spectacularly or have tanked: Now is the time to begin moving at least a portion of the value of your investments into less-volatile areas, such as bond and money market accounts. As each year passes, continue to decrease the amount you have invested in riskier stocks, and increase the amount you maintain in bonds, certificates of deposit, and money market funds. Although the potential for growth in these accounts is limited, so is the potential for loss, and at this stage, you want to know that the money you’ve saved is secure for your child’s education.

Finding out it’s never too late to start saving

Obviously, if you wait until one year before college to set up a college savings account, you probably won’t have as much in it as parents who begin saving the day their child was born. You could let that knowledge defeat you: Why bother saving anything if it’s too little, too late? But you can fight back.

Forget a Coverdell account at this point (unless you’re able to roll over an existing Coverdell account from another child to this one). But a Section 529 plan is still the best bet. Many prepaid tuition plans will be closed to you (they require that you begin making contributions by the time your child reaches a certain grade, which you’ve probably already passed), but all of the savings plans are open, available, and just waiting for your money.

And, although putting money into a tax-deferred or exempt account six months before the first tuition payment is due may not make sense, remember that your child will be attending college for the long haul, and that money could earn a considerable amount inside that account before the last tuition payment is due. Consider making your first payments using current income, or Stafford or PLUS loans (see Chapter 17), and save money in your child’s Section 529 plan for his later college, or even graduate-school, years.