Chapter 7

Weighing the Pros and Cons of Section 529 Plans

In This Chapter

Looking at the upside of 529 plans

Looking at the upside of 529 plans

Dealing with the downside of 529s

Dealing with the downside of 529s

If you discover anything in your research about Section 529 plans, it’s probably that there’s no such thing as a simple answer and that sometimes these plans won’t suit your needs at all. A 529 plan also isn’t for you if your income is very low and you pay tax at the lowest rates, because your student will probably receive full grants. Likewise, if your student is going to give Einstein a run for his money, he may receive a free (or partially assisted) ride to some fabulous institution and won’t need the full amount of your savings.

For the rest, though, Section 529 plans, either by themselves or in concert with other college savings devices, may make a great deal of sense. In this chapter, you find out the benefits of having a Section 529 plan. However, because no plan is perfect, I also alert you to some potential problems of these plans and show you how to work around them.

Pondering the Pros of Section 529 Plans

In Voltaire’s Candide, Dr. Pangloss is forever talking about “the best of all possible worlds.” Well, in the best of all possible worlds, 529 plans are a wonderful, marvelous creation that can pay all qualified postsecondary educational bills (and may even cure the common cold if invested correctly). In any number of scenarios, if you pick the right plan and the right investment strategy for your student, you and your student win. It’s as simple as that.

Higher returns than traditional savings and investment accounts

Saving money is the name of the game, but saving efficiently (and accepting help when offered) is the best way to go about it. Although the federal and state governments won’t actually start a savings account for you or put money into one that you’ve opened, they do provide tools to help your savings grow.

Tax deferrals (postponing when you pay tax)

Tax deferrals (postponing when you pay tax)

Tax exemptions (not paying any income tax at all on earnings)

Tax exemptions (not paying any income tax at all on earnings)

State income tax deductions (sometimes being able to exclude your contributions from your income in the year that you make the contributions)

State income tax deductions (sometimes being able to exclude your contributions from your income in the year that you make the contributions)

Here’s how it works. George and Hannah, who are Maryland residents, have a baby in 2003. They don’t have any savings in the bank, only the money that they currently earn, so they know that paying college costs 18 years down the road may be tough. George and Hannah think it’s wise to start planning now.

They do their research and begin implementing their decisions as soon as the baby arrives. Their first decision is to open a Section 529 plan, and their second is to opt for four years of paid tuition in Maryland’s prepaid tuition plan, which offers not only tax-free qualified distributions but also tax-free contributions. They both attended the University of Maryland, and they feel they received a fine education. It seems like a good choice for their baby.

George and Hannah know that the next 18 years are going to pass quickly and that their son will be heading off to the University of Maryland (or any other college or university, but they’re loyal alumni, so Maryland seems the obvious choice) in 2020. By religiously making their payments into the plan, they know they’ll have four years’ worth of tuition credits when the time comes. They expect that their son, who they expect will be a motivated student, will complete his degree in four years, graduate, and start his working life with a reasonable job in a reasonable company.

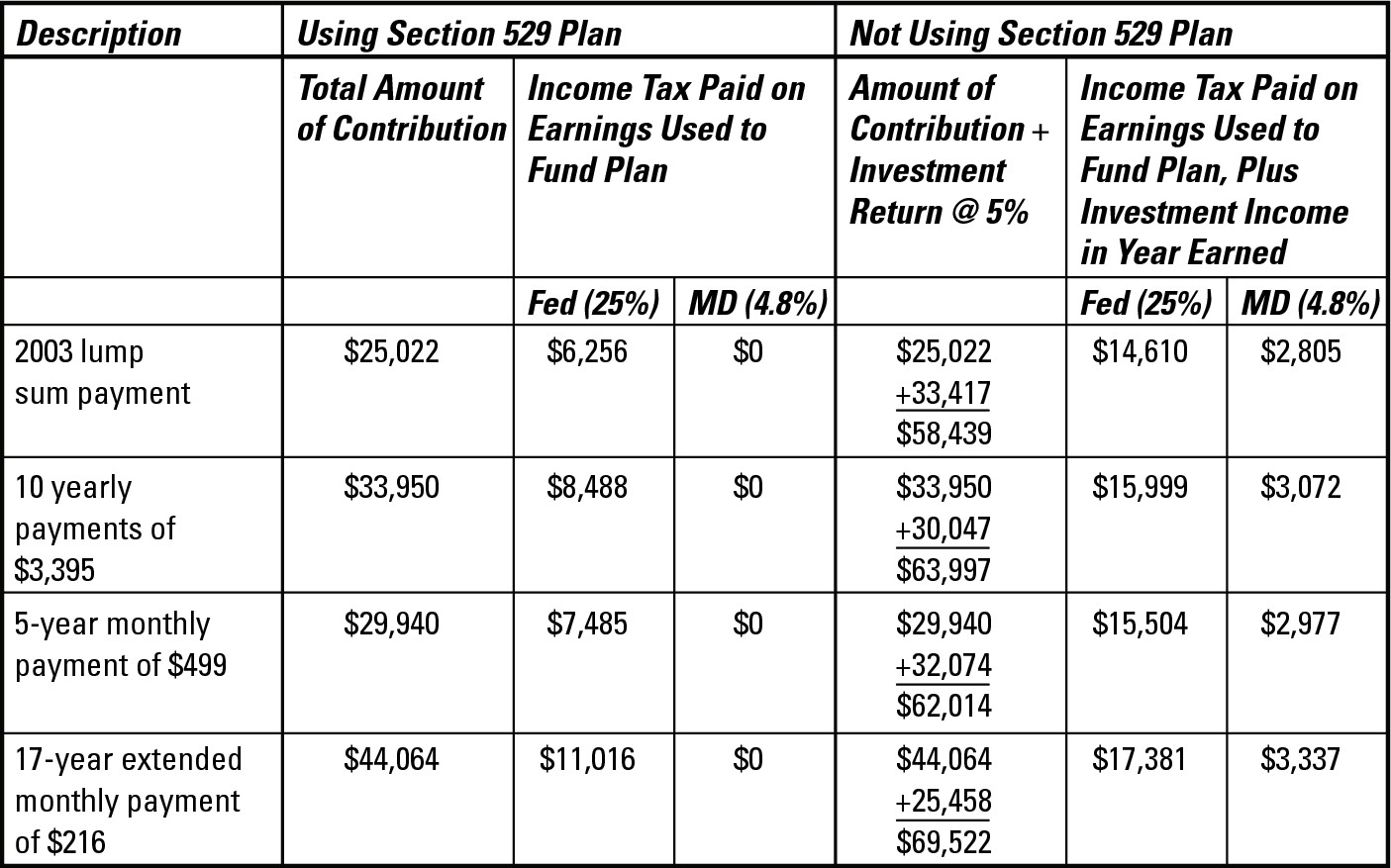

Figure 7-1 shows a comparison of how well George and Hannah will do by investing in Maryland’s prepaid tuition plan as opposed to just saving in the bank for college expenses. Several options are included — prepaying the entire amount in a lump sum, using a 10-year payment plan with annual payments, a 5-year payment plan with monthly payments, and a 17-year payment plan with monthly payments. All comparisons assume that Congress will make the tax-free nature of distributions permanent, that Maryland will continue to provide tax deductions for contributions (and won’t alter the terms of its plan in any way), and that college tuitions and outside investments will both increase by 5 percent each year.

|

Figure 7-1: Comparing saving in a Section 529 prepaid tuition plan with saving in an ordinary investment account, using Maryland (MD) income tax rates. |

|

.jpg)

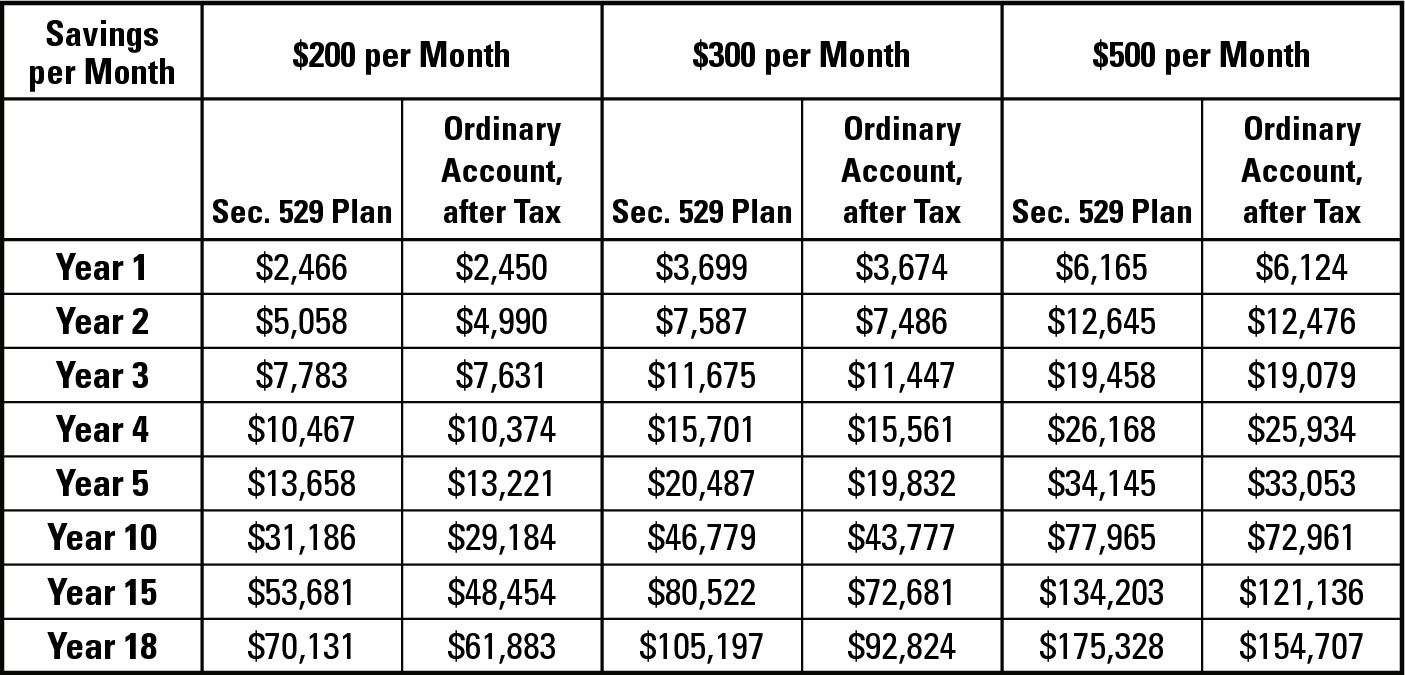

Figure 7-2 illustrates how your money may grow in a 529 plan and how the same amount of periodic savings (whether you use weekly, monthly, or quarterly deposits) will cost you more if you put it into conventional investments outside of a 529 plan. As in Figure 7-1, which shows how the numbers work if you save the same amount each month, all numbers assume a 5 percent annual rate of return, and federal income taxes are calculated at 25 percent. No adjustment is made for state income tax (each state is individual in this regard), and most savings plans don’t carry residency restrictions.

|

Figure 7-2: Comparing saving in a Section 529 savings plan with an ordinary investment account. |

|

Flexibility of funding

Suppose that you’re like George and Hannah — settled in one place with no plans to move — and you’d like nothing better than to see your children graduate from one of your state’s colleges or universities. In that situation, investing in your state’s prepaid tuition plan (if it has one) makes wonderful sense. But you don’t have to be like George and Hannah in order to take advantage of a 529 plan, because there are not only state-run prepaid tuition plans but also savings plans and college-run prepaid tuition plans. So, if you’re saving for the day your child goes to almost any sort of postsecondary school, some 529 plan out there should fit your needs, whatever they are.

Take, for example, Lisa and Sean, who have a newborn and a 15-year-old for whom they haven’t begun saving. Because they’re always on the move from one state to another, they don’t think that investing in a prepaid tuition plan will work for them because of residency requirements built into so many of them. They also like having very few restrictions on where their children can attend postsecondary school. They decide to invest in a 529 savings plan.

With two children of very different ages to save for, Lisa and Sean can open Section 529 plans for each of them but fund the plans unequally, putting more into the older child’s account to beef up savings there and then superfunding the younger child’s account after the older child finishes his education. If any money is left in the older child’s account after his education is complete, Lisa and Sean have the option of making a tax-free rollover (see Chapter 5) of the remaining balance into the younger child’s account.

No taxes to pay (at least for now)

When your distribution program finally begins, any tax on accumulated earnings within the plan is paid by the person to whom, or for whose benefit, the distribution is made. So if you make the distributions for your benefit, you pay the tax; if your designated student is someone else (and it usually is), that person is responsible for any income taxes owed. Currently, as Chapter 6 shows, the income portion of distributions that pay qualified educational expenses aren’t being taxed at the federal level at all, and many states are following suit. Congress may choose to make that exemption permanent, but even if it doesn’t and the provision sunsets in 2010, you and your student will still realize great tax savings by using a Section 529 plan.

For example, suppose that you manage to save $200 per month for 18 years in a 529 account, and that money invested earns a 5 percent rate of return. If you don’t pay any tax, Figure 7-2 shows that you’ll have $70,131: your contributions of $43,200 and interest and dividends of $26,931 that you’ve earned over the 18 years. If you take a qualifying distribution in the first year of college of one-fourth of the total, your distribution will be $17,533, of which $10,800 is your contributions (and therefore not taxed, because you’ve already paid federal income tax on them), and $6,733 represents the income portion of the distribution. If the distribution is made for the benefit of your student for qualifying expenses (and if the sunset provisions described in Chapter 6 are allowed to expire), your student will show $6,733 as income on his income tax return. If your student pays tax at a 10 percent rate, the income tax on that amount will be $673. If the remaining money in the account continues to earn 5 percent per year and the student continues to be taxed on the income portion of all qualifying distributions for the next three years, the total tax paid by the student over the four years of distributions totaling $75,699 will be only $3,253.

On the other hand, suppose that same $200 was invested each month in a traditional savings or investment account (see Chapter 12) and that account earns 5 percent per year in income. Because the income is taxed in each year that it’s earned, after 18 years, the account value is only $61,883 ($8,248 less than the 529 account funded with the same amount of money). The amounts available to be distributed to the student are also less. If remaining balances continue to grow at 5 percent per year over the four years of college, the distribution amounts are $15,471 in the first year, $16,066 in the second, $16,680 in the third, and $17,326 in the fourth, for a total of $65,543, or $10,156 less than the total distributed from the 529 account. And, if the parent (not the child) owns the account, the income earned in each year is taxed at the parent’s rate (usually higher than 10 percent), not the child’s.

This example clearly shows the benefit of tax deferrals, even when the income portion at distribution time isn’t completely tax exempt. The fact that you’ve postponed paying tax lets your money grow faster than if you pay tax yearly on your earnings. The tax-deferred account allows larger distributions to your designated beneficiary for exactly the same dollar cost to you.

Working Around the 529 Shortcomings

Tax deferrals, higher investment returns, and funding flexibility are all powerful motivators, and they may be just the enticements you’re looking for when shopping for a way to invest your savings for college. But all good things carry a price tag, and Section 529 plans are no exception here.

.jpg)

If you save too much or too little

If you save too much or too little

If the plan owner or the designated beneficiary dies

If the plan owner or the designated beneficiary dies

If your designated beneficiary decides, for whatever reason, not to continue beyond high school

If your designated beneficiary decides, for whatever reason, not to continue beyond high school

If you need to rescue the money you’ve saved to pay for one of life’s surprises that often hit you in the face when you’re least expecting it

If you need to rescue the money you’ve saved to pay for one of life’s surprises that often hit you in the face when you’re least expecting it

If you’re aware of what can happen ahead of time, however, you may be able to minimize the damage.

Finagling financial aid implications

The impact that owning a Section 529 plan has on the amount of financial aid available to your student has been the topic of much discussion. And if you aren’t able to save the entire amount you need, you and your student will have to fill out the dreaded U.S. Department of Education’s Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form to determine eligibility for federal financial aid based on the federal methodology. You may also have to complete other aid forms required by individual colleges, who calculate your needs completely differently, using the institutional methodology.

Information that you provide on the FAFSA determines how much your family is expected to contribute to your student’s education. If the cost of that education is higher than your expected family contribution (EFC), your student is eligible for low-cost loans, possibly need-based grants, and/or scholarships. See Chapter 17 for more info on EFCs and the FAFSA.

The type of plan you own: A prepaid tuition plan is counted far more heavily in the financial aid formula than a Section 529 savings plan, and it will reduce your student’s financial aid award on a dollar-for-dollar basis because it is considered upfront as a direct reduction in the cost of attendance.

The type of plan you own: A prepaid tuition plan is counted far more heavily in the financial aid formula than a Section 529 savings plan, and it will reduce your student’s financial aid award on a dollar-for-dollar basis because it is considered upfront as a direct reduction in the cost of attendance.

The amount of the taxable earnings portion of the annual distribution: To the extent that a distribution has a taxable component that is shown on the student’s income tax return, 50 percent of that amount (after being adjusted for the student’s income protection allowance) will be included in arriving at the family’s expected contribution, regardless of whether the distribution is made from a prepaid tuition plan or from a savings plan. Currently, tax-free distributions are not included on the FAFSA; however, no regulations prohibit the U.S. Department of Education from requiring disclosure of even tax-free amounts in determining need or changing its view on the asset classification of 529s, and it may choose that path in the future.

The amount of the taxable earnings portion of the annual distribution: To the extent that a distribution has a taxable component that is shown on the student’s income tax return, 50 percent of that amount (after being adjusted for the student’s income protection allowance) will be included in arriving at the family’s expected contribution, regardless of whether the distribution is made from a prepaid tuition plan or from a savings plan. Currently, tax-free distributions are not included on the FAFSA; however, no regulations prohibit the U.S. Department of Education from requiring disclosure of even tax-free amounts in determining need or changing its view on the asset classification of 529s, and it may choose that path in the future.

The value of the plan if it’s owned by a parent: If you own the plan for the benefit of one of your children, the current value of it needs to be included as a piece of your net assets on your student’s FAFSA even if the Section 529 plan is not for the benefit of the child applying for aid. Although you don’t have to list your assets separately, you may be required to substantiate any number that appears on the FAFSA.

The value of the plan if it’s owned by a parent: If you own the plan for the benefit of one of your children, the current value of it needs to be included as a piece of your net assets on your student’s FAFSA even if the Section 529 plan is not for the benefit of the child applying for aid. Although you don’t have to list your assets separately, you may be required to substantiate any number that appears on the FAFSA.

The relationship between the plan owner and the plan beneficiary: If you’re the owner of a savings plan and your child is the beneficiary, a maximum of 5.6 percent of your 529 plan is factored into your student’s expected family contribution. If you’re the owner and you (or your spouse) are the beneficiary, that percentage increases to a maximum of 35 percent if you have no other dependents, less if you have dependent children. If you own a plan for the benefit of a grandchild or a nonrelative, the value of your plan is excluded from any aid calculation.

The relationship between the plan owner and the plan beneficiary: If you’re the owner of a savings plan and your child is the beneficiary, a maximum of 5.6 percent of your 529 plan is factored into your student’s expected family contribution. If you’re the owner and you (or your spouse) are the beneficiary, that percentage increases to a maximum of 35 percent if you have no other dependents, less if you have dependent children. If you own a plan for the benefit of a grandchild or a nonrelative, the value of your plan is excluded from any aid calculation.

If, after FAFSA has calculated your student’s expected family contribution, the amount available to you in your Section 529 isn’t adequate to meet the contribution amount, you may need to explore other funding sources, including scholarships (see Chapter 16), federal work-study funds, and student loans (see Chapter 17).

When the plan owner dies

Dying is not something you (or anyone) want to contemplate, and especially not before completing the job you’ve started: educating your children. But sometimes it happens. If it happens to you, you want to be certain that you’ve left all your affairs as tidy as you can. And that includes your 529 plan.

.jpg)

Should your family members find themselves dealing with the aftermath of your death, you won’t be around to help them to sort it out. Make sure that your affairs are in order now, and then make certain that they stay that way.

Transferring plan ownership

This advice may seem simple and obvious, but many a plan has come to grief through death and divorce. Take, for example, David and Lilly. David, a widower, has a daughter from his first marriage, for whom he has set up a Section 529 plan. When he marries Lilly, he names her as his successor plan owner. David and Lilly go on to have two children of their own. Five years later, David dies suddenly, and Lilly becomes the plan owner.

As a result of David’s death and Lilly’s assuming ownership of the 529 account, she’s now in control of the assets. She and David’s daughter have never seen eye-to-eye, and Lilly decides to change the beneficiary designation to one of her children. Because Lilly’s children are half siblings to David’s daughter, this beneficiary change is allowable. The money David saved to send his own daughter to college is now being used to send David and Lilly’s child to school, and David’s daughter needs to fend for herself.

.jpg)

Gift/GSTT Consequences

If you’ve been able to superfund your Section 529 plan, taking advantage of the five-year election explained in Chapter 5, where you give up to $55,000 per donee in a single year and then plan to spread those gifts out over five years, you need to read this.

Section 529 plans have a unique place in the rules and regulations surrounding Gift and Generation-Skipping Transfer (GST) tax. After you put the money into the plan and designate a beneficiary, it counts as a completed gift. From the perspective of the Gift and GST rules, you’ve given up “all right, title, and interest” in the money. Except you really haven’t. Provided the money you’ve gifted goes into an account that you own, you remain the plan owner and are therefore in control of the assets. You can change the investment strategy (but not the investments themselves), and you can even change the beneficiary, to the point of terminating a plan entirely and taking the money back. You will pay a penalty, but you’ll have your money back. So much for giving up “all right, title, and interest.”

Still, because the IRS considers the gift a completed transfer, you’re entitled to use your annual exclusion to gift money into these accounts (see Chapter 3). And, when you die, because you’ve given the money away previously (even though you really haven’t), it’s not counted in your estate, even though you are (or were, because you’re now dead) the plan owner.

The only piece that may be pulled back into your estate and counted for estate and/or the GST tax is that amount that you superfund (see Chapter 3). If you die during the five years that constitute your election period, any amounts for which you haven’t filed a gift tax return yet, if you were required to file one, are included in the value of your estate.

For example, Moe sets up 529 accounts for his two grandchildren. He puts $55,000 into each one in 2002 and makes the election on his 2002 Form 709 (U.S. Gift and GST Tax Return). He doesn’t make any other gifts to the kids in the following years, so he isn’t required to file any more gift tax returns. Moe passes away in 2004. Because he was alive during only three of the five years of his election period, his estate tax return must include $44,000 (2 years x $11,000 annual exclusion x 2 grandkids), even though the money is safely tucked away inside the 529 plans. The money for the annual exclusion amounts that would have been made had Moe not died doesn’t return to his estate; only the value does for the purpose of calculating Moe’s estate tax.

Estate tax consequences

With the exception shown in the preceding section, when a five-year election has been made in order to jump-start a Section 529 plan and then the plan owner dies before the end of the five-year period, there are no estate tax consequences for the plan owner. Even though you may be considered the plan owner while you’re alive, the account carries sufficient restrictions to give the appearance that you lack total control over the account, even before your death. None of the assets appear on your estate tax return, and your estate pays no additional tax due to your ownership of these plans.

Death of a designated beneficiary

Sometimes the unthinkable happens, and the person for whom you’ve been saving money all these years dies. In these situations, the rules governing Section 529 nonqualified distributions, rollovers, transfers, and terminations ease, although they don’t entirely disappear.

If a distribution was made to the beneficiary, or to his estate after his death, and the distribution wasn’t entirely used for qualified educational expenses, the income portion of that amount is taxable to the student or his estate on the appropriate income tax return. Because it was clearly not the student’s intention to use the money for nonqualified expenses, the 10 percent penalty is waived.

And that is usually the only tax consequence to the designated beneficiary, or to his estate (assuming that he does not have a taxable estate, because the distribution does become part of his estate). Because you remain the plan owner (and therefore nominally in control of the plan assets), what happens next with the remaining money in the account is your call.

You have a plan that has no designated beneficiary (as I explain in Chapter 5, having a designated beneficiary is a requirement of 529 plans), so you need to name a new one or terminate the plan. As in any change of a designated beneficiary, you can merely change the designation in an existing account, add the funds from the old account to a different existing account for a new beneficiary, or roll over the funds from the old account into a new account.

Even if you’ve already done a tax-free rollover within the last 12 months or changed your investment strategy in an existing account, any rollover will be tax-free (provided it is completed within 60 days). The 12-month rule is suspended when a designated beneficiary dies. The IRS recognizes that you are not doing this through choice, but necessity.

Finally, should you choose to terminate the account and retrieve your savings, you’ll have to pay income tax on the accumulated earnings in the account, but the 10 percent additional penalty will be waived.

Making choices if your child skips college

When little Joey grows up, he may no longer want to be a rocket scientist but would rather spend his life surfing. Or maybe Catherine’s biggest desire has shifted from studying the law to living on a Katmandu commune. Life and differing expectations sometimes throw curveballs at you, and what may have been your desire doesn’t fit into the game plan of your designated student.

When you save in a Section 529 plan, you’re not saving for a certain event but one that has a reasonable probability. And sometimes your reasonable expectations are not realized, and the money that you saved specifically for that purpose won’t be needed. That’s when you can gnash your teeth, rip out your hair, and scream at the heavens because, had you known, you would have put all that money into a traditional investment account (see Chapter 12), paid the income tax on an ongoing basis, and never given any thought to how to deal with this unforeseen set of circumstances.

Section 529 does offer you some flexibility when you face the problem of money in your account but no qualifying student to spend it. Still, the day you first understand that you didn’t need to do all this planning for this student is the day you have to begin calculating what to do with the funds you’ve saved.

Changing beneficiary designations

When you realize that your designated beneficiary isn’t going to attend college, your first thought may be to change the designated beneficiary on the account. Good thought. If you have more than one student for whom you bear some financial responsibility, you can do one of three things:

Change the beneficiary name on the existing account

Change the beneficiary name on the existing account

Open a completely new account for the new beneficiary

Open a completely new account for the new beneficiary

Roll the value of the old account into an already existing account for the new beneficiary (provided, of course, that the total of the two accounts doesn’t exceed the state limit on account size)

Roll the value of the old account into an already existing account for the new beneficiary (provided, of course, that the total of the two accounts doesn’t exceed the state limit on account size)

So long as you change the designated beneficiary to a new beneficiary who bears a family relationship to your previous designated beneficiary (as explained in Chapter 5), these maneuvers will have no adverse effects on you, your old beneficiary, or your new one.

You may also choose to terminate an existing account (suppose that your former beneficiary is a resident in one state, and your new one lives in another) and roll over the fund balance into a completely different account, tax free, provided the transfer is completed with 60 days. If you can’t get the new fund up and running within that 60-day period, you’re out of luck. You (not the designated beneficiary) will be taxed on the accumulated income in the fund, and then you can tack on an additional 10 percent penalty.

.jpg)

Terminating the plan

When your designated student clearly has no desire to continue his education, you may have no other prospective student waiting in the wings. In this case, the obvious choice is to terminate your plan.

This whole scenario may work well for you if your designated beneficiary is an absolute wizard who is receiving a full-paid academic scholarship (in which case, the 10 percent penalty doesn’t apply; see the next section). You may not feel as keen, however, about giving control over a lump sum of money to a child who’s not living up to potential. If your plan will terminate only in favor of the designated beneficiary, you may want to consider making an intermediate tax-free rollover (as described in Chapter 5) to an account that will allow you to terminate in favor of yourself.

.jpg)

Limiting penalties for too much money

Your fondest dreams have been borne out, and your student is headed for a free ride. Or, more realistically, your student received a darn good scholarship and will need only a portion of the money you’ve saved to pay the difference. You have many options for using this extra money, and most of them revolve around your family circumstances and your thoughts about money. Here are a few of your options that will minimize the size of Uncle Sam’s bite:

You may choose to make distributions to your student equal to or less than the scholarship amount without paying a penalty on the income portion. Your student is responsible for any income tax on the income portion of the distribution that he’s not using to pay for qualified educational expenses, but an additional 10 percent penalty will not be tacked on. Remember, lots of incidentals need to be paid for that don’t fall under the category of “qualified educational expenses.” Chapter 10 shows how this scenario works.

You may choose to make distributions to your student equal to or less than the scholarship amount without paying a penalty on the income portion. Your student is responsible for any income tax on the income portion of the distribution that he’s not using to pay for qualified educational expenses, but an additional 10 percent penalty will not be tacked on. Remember, lots of incidentals need to be paid for that don’t fall under the category of “qualified educational expenses.” Chapter 10 shows how this scenario works.

You may want to roll over part, or all, of the extra into a Section 529 plan for another child or a grandchild. If you haven’t already made a tax-free rollover in the previous 12 months, you’re free to do this, and jump-start a new account or supercharge one that’s been a bit anemic, as described in the section “Deciding what to do if your child doesn’t attend college,” earlier in this chapter.

You may want to roll over part, or all, of the extra into a Section 529 plan for another child or a grandchild. If you haven’t already made a tax-free rollover in the previous 12 months, you’re free to do this, and jump-start a new account or supercharge one that’s been a bit anemic, as described in the section “Deciding what to do if your child doesn’t attend college,” earlier in this chapter.

You may want to hold off doing anything, at least for a while. Many people continue on after college, and your student could be one of those. Although you may have thought that your ability to pay would stop after college, the fact that your child has received this additional assistance may enable her to continue on to graduate or professional school without taking loans. Remember, there is no age limitation on Section 529 plans — a student may be any age to qualify.

You may want to hold off doing anything, at least for a while. Many people continue on after college, and your student could be one of those. Although you may have thought that your ability to pay would stop after college, the fact that your child has received this additional assistance may enable her to continue on to graduate or professional school without taking loans. Remember, there is no age limitation on Section 529 plans — a student may be any age to qualify.

Minimizing the blow for retrieving savings to weather hard times

Planning and plotting are part of the human condition, and after you have children, your propensity for doing more than going with the flow increases exponentially. That’s why you’ve been investigating and, I hope, saving in a 529 plan in the first place. But sometimes your life may make a U-turn, and items that you may have thought were sacrosanct now need to be put on the table in order to deal with immediate family survival. Thinking of the distant future seems hard when the immediate present is looking grim.

In these cases, you may find it necessary to access the funds you’ve been so carefully saving in your Section 529 plan. Because 529s are designed for paying for college, you’re not really supposed to use that money for something else — that’s why the IRS charges you a penalty when you do. Still, the beauty of these plans is that they allow it, with some conditions.

Nonqualified distributions to yourself or your designated beneficiary that trigger additional tax

Uncertain world economies often lead to unstable family economies. Suppose that your income has dropped for any reason (loss of one salary, wage reductions, or investment income decline) or your expenses have increased significantly. You may find that you not only can’t continue to fund your 529 plan but also need to liberate some money in order to pay your bills.

You could beat yourself up over this situation, because you put the money aside for your student. But there’s a reason why 529 plans are regarded as the parents’ (not the student’s) assets when determining the financial need of a student, and this is it. You can take a distribution of some (or all) of the money you’ve saved from a prepaid tuition plan or a savings plan.

That said, it’ll cost you. If your investments have appreciated in value, you’ll pay the income tax on the accumulated earnings at your income tax rate, plus a 10 percent penalty for a nonqualified distribution. It’s not a perfect solution, but in the right situation, it may be the only one that makes sense for you.

.jpg)

Nonqualified distributions to or for the benefit of the beneficiary, without penalty

Another benefit of Section 529 is the way it separates out your unforeseen circumstances from your designated student’s. After all, even though you own the plan, you’ve put the money aside for the student’s use, and you have received favorable gift tax treatment on that premise. Accordingly, although you may have to pay a penalty if you take back money from your student’s Section 529 plan, if your student needs money and takes a distribution from the plan, it may be subject only to income tax on the earnings (paid at the student’s tax rate, not yours), without the 10 percent penalty.

These exceptions, covered in detail in Chapter 5, include the following:

Distributions that would have been qualified except for the fact that your student has received scholarship and/or grant money or other educational benefits from another source.

Distributions that would have been qualified except for the fact that your student has received scholarship and/or grant money or other educational benefits from another source.

Distributions used to pay enough educational expenses to qualify for the Hope or Lifetime Learning Education Credits. Remember, in this case, the student needs to claim the credit, so he can’t be listed as a dependent on your income tax return, which may limit the value of this technique. Of course, if you (or your spouse) are the beneficiary as well as the owner of a 529 plan, using this becomes much more valuable to you.

Distributions used to pay enough educational expenses to qualify for the Hope or Lifetime Learning Education Credits. Remember, in this case, the student needs to claim the credit, so he can’t be listed as a dependent on your income tax return, which may limit the value of this technique. Of course, if you (or your spouse) are the beneficiary as well as the owner of a 529 plan, using this becomes much more valuable to you.

Distributions that are made on account of a severe disability or because of the impending death of the designated beneficiary.

Distributions that are made on account of a severe disability or because of the impending death of the designated beneficiary.

In the first two cases, the distributions would have qualified except for the receipt of assistance from another source or because of the need to have some taxable income against which to use a tax credit; here, the lack of a penalty makes perfect sense. These are clearly situations where the student is a student, is attending a qualified educational institution, and is using any money he receives to forward his education. All that is happening here is that the income from the Section 529 plan is reverting back to pre-2002 treatment and is being taxed at the student’s applicable tax rate.

In the third case, where the designated beneficiary faces a situation that will most likely preclude him from attending a postsecondary school, he is not being penalized for something that is far beyond his control. Much as distributions are allowable out of an IRA for medical expenses even though the payment is made before the beneficiary reaches the age of 59 1/2, distributions from a Section 529 plan for grave medical cause are subject to income tax on the earnings portion, but no penalty.

Having money left over after graduation

Graduation day has come and gone, and your designated beneficiary is now confidently heading out into the workplace, credentials in hand, and with no immediate intention of continuing on for an advanced degree, which you may have no intention of paying for anyway. And you’re feeling fairly good about yourself, knowing that your good planning and careful attention all the way through the process has helped your student to reach this point.

Now the only fly in the ointment seems to be that you planned too well, and you still have money left in your Section 529 savings kitty. If you used a prepaid tuition plan, while it’s less likely that you’ll have anything left, you may still have some unused tuition credits that you need to deal with. Oops!

Actually, good for you! You planned and then carried through. You had no way of knowing how much you would actually need, but you managed to save more than enough. So now on to the next phase — figuring out how to deal with the excess while minimizing, or even eliminating, any tax bite.

Remembering that you own the unused funds

When you funded this account for your prospective student, you may have filed a gift tax return, essentially giving this money to that designated beneficiary for the purpose of his future education. It would make sense, then, that now that the education is complete, she’d get what’s left.

Wrong! You’ve been the owner of the account from Day 1, and nothing has changed here. The fact that your designated beneficiary has now graduated only means that she no longer needs the funds. You remain the plan owner.

.jpg)

Changing beneficiaries

Even if your plan doesn’t require that you take action immediately (or within a fixed time), all plans have provisions written in to prevent them from existing forever. Congress, the IRS, and all the state treasuries want to know that you’re planning on spending that money on education. Although they’ll grant you a bit of leeway in figuring out what to do with your excess, you need to make a decision. And that decision is a fairly basic choice: You need to terminate the account or change the beneficiary designation, either through a simple change of beneficiary on the current account or a tax-free rollover into a new or already existing account for the new designated beneficiary.

If you choose the rollover option, the rules are the same as for any rollover: Your new designated beneficiary must belong to the same family as your original designated beneficiary, in the allowed relationships listed in Chapter 5. You can roll the excess into a brand-new 529 plan for the new designated beneficiary (a younger child, perhaps) or into an already existing plan. Don’t forget that you can also use this opportunity to change your investment strategy. For example, you may not want to be as conservative in your choices with a younger beneficiary as you may have been with the former beneficiary.

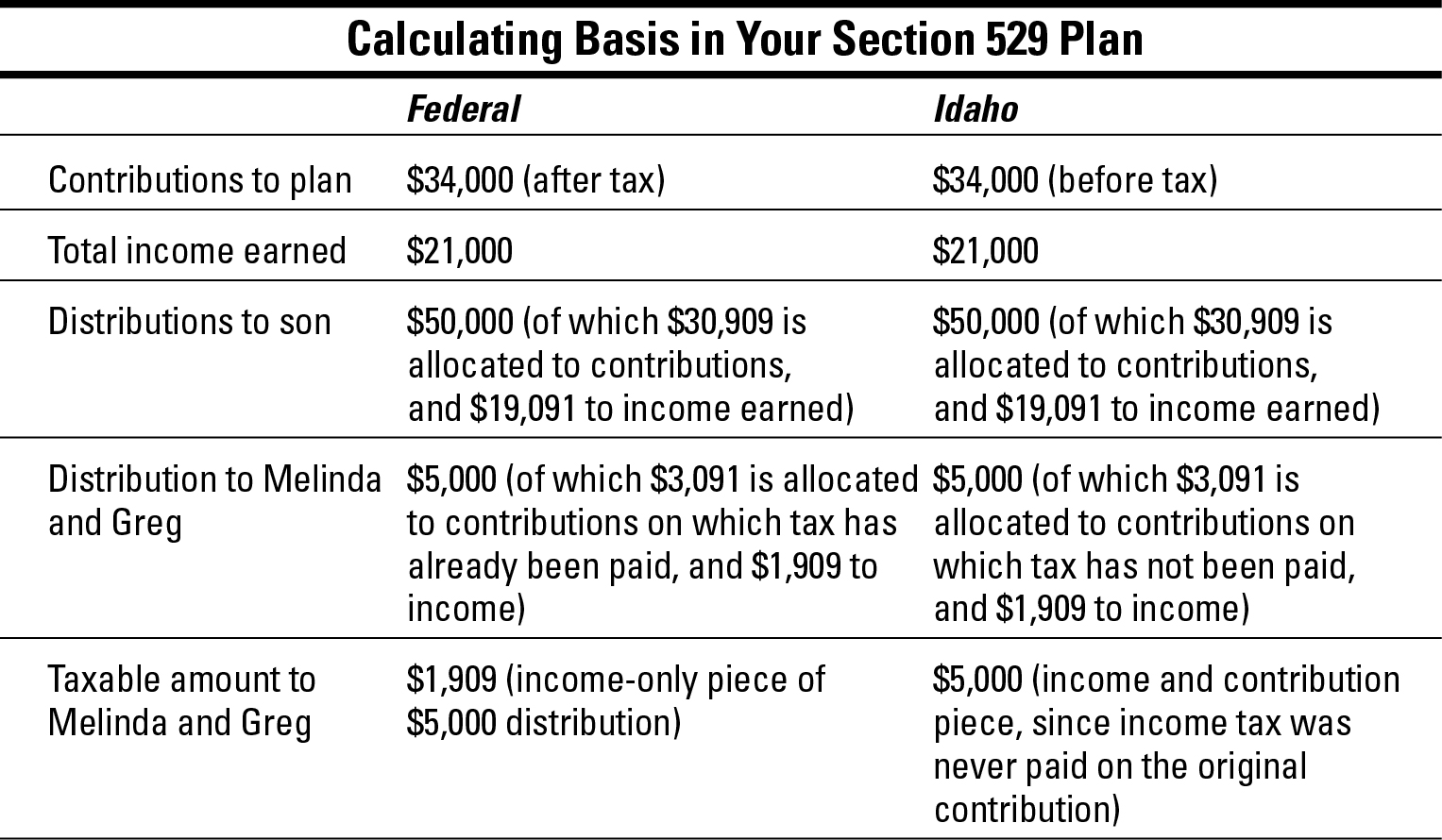

Tracking the basis in your Section 529 Plan

No matter what type of plan that you own and how much it might be growing, you always need to keep track of your basis, or how much money you or anyone else has put into the account. If you live in a state that gives you partial or full credit for contributions into a Section 529 plan, you’ll need to keep two separate sets of records for this reason: Your federal contributions will be made after you’ve already paid income tax on the money, while your contributions for state purposes may be made before state income tax is paid. By knowing your basis, you can calculate just how much of any distribution from the plan represents taxable earnings.

For example, Melinda and Greg, who are Idaho residents, have a Section 529 plan for their son, and they put $2,000 a year into it for 17 years. After their son graduates from college (having taken $50,000 in qualified distributions on which the earnings were tax-exempt), $5,000 is still left in the plan. As they have no other children and no one whom they wish to name a designated beneficiary, they terminate the account and receive the final distribution. The following table shows how Melinda and Gregg calculate the taxable portion of their distribution:

Calculating taxes on unused funds

After you see all the members of your family through college and into the great working world beyond, you may finally reach a point where you still have excess funds in the very last Section 529 plan that you own, and no one is left for whom to fund a new account. (Remember, if your children have children of their own at this point, you can always roll over the remainder into new accounts for your grandchildren, as described in Chapter 5.) If you don’t have anyone left to fund for, that’s okay — you’ve really done a great job, and your students are all now well able to stand on their own two feet.

Still, now you really must terminate your last plan and get out of the 529 business. At this time, you need to request a distribution from your plan manager of the entire balance. This is clearly a nonqualified distribution, and you’ll have to pay income tax on the earnings portion of the distribution and a 10 percent penalty. As you write your check to the United States Treasury (and to your state treasurer, if you live in a state with an income tax), focus on all the money you’ve saved over the years by deferring this tax and on all the benefits you and your students have reaped. Approaching the task with this attitude should make writing these checks a bit less painful.