Chapter 8

The Changing World of Coverdell Education Savings Accounts

In This Chapter

Exploring the fundamentals of Coverdell accounts

Exploring the fundamentals of Coverdell accounts

Contributing to the account

Contributing to the account

Distributing the money

Distributing the money

Making changes to the account

Making changes to the account

For people trying to save money for college, 2002 was a very good year. Not only were the rules regulating Section 529 plans (see Chapter 5) overhauled to make the plans more flexible and less taxable, but Congress also completely revamped and expanded the rules surrounding the old Education IRA’s, going so far as to rename them Coverdell Education Savings Accounts (ESAs), after the late Senator Paul Coverdell (R-Georgia), who was the chief sponsor of the legislation regulating these accounts. The revamp has been monumental, both in size and in scope, completely changing the old Education IRA (which was fairly useless as a significant college savings device) into a mover and shaker in the field of educational savings.

In this chapter, you discover the ins and outs of the new Coverdell Education Savings Accounts, and you find out why so many people (your banker, your broker, you child’s kindergarten teacher) all want you to start investing, and investing now. You also see how the improvements really do qualify as improvements, and you’re alerted to red flags and warnings along the way.

Covering the Basics

Coverdell ESAs are savings plans described in Section 530 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). They’re accounts that Congress created to allow you to save now for future educational expenses, whether primary, secondary, or postsecondary, of a designated beneficiary.

You can invest money in Coverdell accounts in a variety of ways: stocks, bonds, money market accounts, certificates of deposit, and so on, although you may not invest in life insurance policies. And I really mean that you can invest; under the Coverdell rules (and unlike Section 529 rules), if you designate yourself the one responsible for all decisions on this particular account (also known as the responsible adult, who must be the parent or legal guardian of the minor child; see Chapter 9), you keep control of the money and make all the investment decisions for your child’s account. Over the years, the investments will hopefully earn significant income through interest, dividends, and capital gains, until the time that the account is closed.

You pay no income tax on the income when it’s earned, and as distributions are made from these accounts to your designated beneficiary for qualified educational expenses, the income portion of the distribution is not taxed, either to you or to your student.

Understanding Coverdell changes

When these accounts were first introduced in 1997 as Education IRA’s, they were limited to $500 a year aggregate contribution per student, and distributions could be used to cover only postsecondary expenses. If you were thinking of making a contribution into any plan, you probably would’ve chosen a Section 529 plan, which had fewer restrictions and allowed you to maintain some contact with your money. Basically, the old Education IRA was a nonstarter for most people because contribution limits were fairly pathetic, and much better ways to save money for college were available.

In the new world of Coverdell (same code section, different name), the aggregate contribution limit has been raised to $2,000 per year, the definition of “qualifying student” has been hugely expanded, and you may now contribute to both a Coverdell account and a Section 529 plan for the same beneficiary in the same year. With all these factors, plus an increase in the income phaseout limitations present under Coverdells but not 529 plans, these accounts can become useful savings tools for many families.

Looking at the major differences between Coverdell accounts and 529 plans

On their faces, Coverdell ESAs and Section 529 plans seem to be two peas in a pod: Both are designed to encourage savings for higher education, and after passage of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, both now allow tax-free distributions if they’re used to pay for qualified educational expenses.

Still, Sections 529 and 530 (governing Coverdell ESAs) of the Internal Revenue Code are quite different, and the savings plans that they govern contain several crucial differences. Among them are the following:

Coverdell accounts have strict limits on the amount of income any contributor (with the exception of a corporate or charitable one) may earn in a particular year in order to make contributions into the account; Section 529 plans carry no such restriction.

Coverdell accounts have strict limits on the amount of income any contributor (with the exception of a corporate or charitable one) may earn in a particular year in order to make contributions into the account; Section 529 plans carry no such restriction.

Coverdell accounts have strict limits on the amount that may be given into any account for a specific designated beneficiary in each year, while Section 529 plans do not (only overall plan maximums). In addition, contributions may not be made after age 18 for the designated beneficiary of a Coverdell account. Section 529 plans have no beneficiary age limit. Accordingly, 529 plans have the capacity to transfer significant amounts of wealth, while Coverdell accounts are much more modest in size.

Coverdell accounts have strict limits on the amount that may be given into any account for a specific designated beneficiary in each year, while Section 529 plans do not (only overall plan maximums). In addition, contributions may not be made after age 18 for the designated beneficiary of a Coverdell account. Section 529 plans have no beneficiary age limit. Accordingly, 529 plans have the capacity to transfer significant amounts of wealth, while Coverdell accounts are much more modest in size.

Assets inside a Coverdell account are considered to be owned by the designated beneficiary and are therefore counted as the student’s asset when calculating financial aid formulas (see Chapter 17), while asset ownership in a Section 529 plan is much more confusing, depending on how you look at it. For gift and Generation-Skipping Transfer tax purposes, the assets have transferred to your designated beneficiary, while for financial aid purposes, the assets are counted as the account owner’s.

Assets inside a Coverdell account are considered to be owned by the designated beneficiary and are therefore counted as the student’s asset when calculating financial aid formulas (see Chapter 17), while asset ownership in a Section 529 plan is much more confusing, depending on how you look at it. For gift and Generation-Skipping Transfer tax purposes, the assets have transferred to your designated beneficiary, while for financial aid purposes, the assets are counted as the account owner’s.

If you live in a state that gives a deduction or credit for Section 529 contributions, no state gives the same benefit for Coverdell ESA contributions. All your contributions will be made “after tax” for both federal and state purposes.

If you live in a state that gives a deduction or credit for Section 529 contributions, no state gives the same benefit for Coverdell ESA contributions. All your contributions will be made “after tax” for both federal and state purposes.

Qualifying students under Section 530 include everyone from kindergartners through college and graduate school students, and you may pay a wide variety of elementary and secondary educational expenses with distributions from Coverdell accounts (in addition to the qualified educational expenses of eligible postsecondary institutions). Under Section 529, only postsecondary students are qualified, and you may use plan distributions to pay only the qualified educational expenses of eligible postsecondary institutions.

Qualifying students under Section 530 include everyone from kindergartners through college and graduate school students, and you may pay a wide variety of elementary and secondary educational expenses with distributions from Coverdell accounts (in addition to the qualified educational expenses of eligible postsecondary institutions). Under Section 529, only postsecondary students are qualified, and you may use plan distributions to pay only the qualified educational expenses of eligible postsecondary institutions.

Knowing who owns the account

No matter who makes contributions into a Coverdell ESA, the IRS considers the designated beneficiary to be the owner of the assets. If you structure the accounts for your children correctly, though, you can remain in control of the assets by naming yourself the responsible adult, or the person in control of the account, when you open the account.

If, when your children turn 18, your philosophy is to turn their finances over to them to help them establish their independence, or if you feel your child at that age is more savvy about money and investments than you’ll ever be, you may put your child in control at that time, although you don’t have to.

.jpg)

Identifying qualifying students

Age limitations at time of contribution

In general, you have 18 years in which you, or anyone else, for that matter, can fund a Coverdell ESA for your child, from his date of birth until the day before his 18th birthday. After that, you’re done. No matter how much or how little you’ve managed to put away for that student, you can’t add any more to the account. Any increases from now until the termination of the account will have to come from the earnings off your good investments.

Age limitations at time of distributions

Coverdell ESAs must be completely distributed by the time your designated beneficiary hits his or her 30th birthday. If money is still left in the account on that date, it must be distributed within 30 days, and any earnings on it will be taxed to the beneficiary, plus whacked with a 10 percent penalty.

Saving for disabled and special-needs students

While members of Congress have essentially stated that your children should have completed their educations by their 30th birthday, they do also recognize that some students will spend their lives in special schools. Accordingly, if you’re the parent or grandparent of a special-needs student, there are no age limitations either on contributions or distributions on behalf of these students.

.jpg)

Recognizing qualified education expenses

Qualified education expenses under Code Section 530 are those expenses that you’re required to pay (or figure out some other way of meeting) if your student is to enroll at an eligible school. Just as in Section 529, though, many other expenses may be qualified, depending on the requirements of the school and of the particular program your student may be enrolled in.

First, you need to know what constitutes an “eligible school.” For the purposes of IRC Section 530 and Coverdell ESAs, eligible schools include all public, private, or religious schools that provide either primary or secondary education as determined under their applicable state laws. All postsecondary educational institutions that are qualified under Section 529 also qualify as eligible schools under Section 530.

.jpg)

Qualified expenses for elementary and secondary education

In addition to tuition and mandatory fees, other elementary and secondary education expenses may be eligible for payment using Coverdell distributions. Some expenses may seem obvious; others may surprise you:

Books, supplies, and equipment related to enrollment: In these days of shrinking school budgets, parents need to supply their children with more and more of what used to be considered necessary school supplies. Amounts that you spend for pens and pencils, notebooks, erasers, and the like are included here. You may also use a distribution from your Coverdell to pay for textbooks and any other required reading material that’s not supplied by the school district.

Books, supplies, and equipment related to enrollment: In these days of shrinking school budgets, parents need to supply their children with more and more of what used to be considered necessary school supplies. Amounts that you spend for pens and pencils, notebooks, erasers, and the like are included here. You may also use a distribution from your Coverdell to pay for textbooks and any other required reading material that’s not supplied by the school district.

Academic tutoring related to enrollment: The math or science tutor (or even a dance instructor if your child is a dancer attending a school for the performing arts) is covered here, but your child’s extracurricular piano or dance lessons are not.

Academic tutoring related to enrollment: The math or science tutor (or even a dance instructor if your child is a dancer attending a school for the performing arts) is covered here, but your child’s extracurricular piano or dance lessons are not.

Special-needs services for students with special needs or disabilities: If your student needs a one-on-one aide with him and the school doesn’t cover the expense, this service qualifies, as does special equipment necessary to accommodate him. However, when assessing what qualifies here, remember that the regulations regarding special needs haven’t been issued yet.

Special-needs services for students with special needs or disabilities: If your student needs a one-on-one aide with him and the school doesn’t cover the expense, this service qualifies, as does special equipment necessary to accommodate him. However, when assessing what qualifies here, remember that the regulations regarding special needs haven’t been issued yet.

Room and board, but only if a requirement of attending that particular school: Clearly, if you send your child to a boarding school 300 miles from your home, room and board would be required; if, however, you live in the next town, this expense may be questionable.

Room and board, but only if a requirement of attending that particular school: Clearly, if you send your child to a boarding school 300 miles from your home, room and board would be required; if, however, you live in the next town, this expense may be questionable.

Uniforms, when required by the school: The cost of voluntary school uniform programs doesn’t constitute a qualified educational expense, nor does the annual cost of buying your child school clothes.

Uniforms, when required by the school: The cost of voluntary school uniform programs doesn’t constitute a qualified educational expense, nor does the annual cost of buying your child school clothes.

Transportation, when required by the school: The expense of driving your student to and from school every day doesn’t qualify, but the price you’re charged for the mandatory school bus does. As more and more communities begin to charge families for the cost of transportation to and from school, this expense will become an item that more people may choose to pay from their Coverdell accounts.

Transportation, when required by the school: The expense of driving your student to and from school every day doesn’t qualify, but the price you’re charged for the mandatory school bus does. As more and more communities begin to charge families for the cost of transportation to and from school, this expense will become an item that more people may choose to pay from their Coverdell accounts.

Supplementary items and services, including extended day programs: If your child attends an after-school program or an extended day program at his or her school, you may choose to pay these costs from your Coverdell account. The payment must be made to the school, however, so once again, those extracurricular piano lessons probably aren’t covered here.

Supplementary items and services, including extended day programs: If your child attends an after-school program or an extended day program at his or her school, you may choose to pay these costs from your Coverdell account. The payment must be made to the school, however, so once again, those extracurricular piano lessons probably aren’t covered here.

Computers, printers, other peripherals, Internet access, software, and so on: To the extent that you can document that the use of this equipment and programming is to benefit your student’s education, even if you may be the primary user of this equipment, you may pay for it by using a qualified Coverdell distribution. Items that aren’t used for educational purposes, though, don’t count as qualified expenses, so the video games, the joystick you buy for your computer, and any gaming, sports, or hobby software don’t qualify.

Computers, printers, other peripherals, Internet access, software, and so on: To the extent that you can document that the use of this equipment and programming is to benefit your student’s education, even if you may be the primary user of this equipment, you may pay for it by using a qualified Coverdell distribution. Items that aren’t used for educational purposes, though, don’t count as qualified expenses, so the video games, the joystick you buy for your computer, and any gaming, sports, or hobby software don’t qualify.

Qualified expenses for higher education

When your student reaches the halls of higher learning (or any other school after he’s completed high school), the rules regarding what constitutes a qualified expense for the purposes of Coverdell distributions change. The higher education rules fall in line with those for Section 529 plans (see Chapter 5), which makes sense. The 2001 tax law changes focused on adding primary and secondary education; it pretty much left alone what was already in place regarding postsecondary education.

In general, the following lists constitutes qualifying educational expenses for postsecondary education payable by tax-free distributions from Coverdell accounts:

Tuition and mandatory fees at eligible educational institutions: For a school to qualify, it needs to be able to participate (but doesn’t have to if it chooses not to) in federal financial aid programs administered by the Department of Education.

Tuition and mandatory fees at eligible educational institutions: For a school to qualify, it needs to be able to participate (but doesn’t have to if it chooses not to) in federal financial aid programs administered by the Department of Education.

Required books, supplies, and equipment: The books on the lengthy list that every professor hands out on the first day of class, laboratory equipment, and any required computer equipment (including peripherals) qualify. Your child’s cell phone, which you may require for your peace of mind, does not.

Required books, supplies, and equipment: The books on the lengthy list that every professor hands out on the first day of class, laboratory equipment, and any required computer equipment (including peripherals) qualify. Your child’s cell phone, which you may require for your peace of mind, does not.

Room and board expenses: These expenses are qualified only if

Room and board expenses: These expenses are qualified only if

• They’re paid directly to the school itself and your student is attending class at least half time or

• They don’t exceed the amount the school budgets for these expenses, provided your designated beneficiary is at least a half-time student.

If the room and board fees that you pay directly to the school exceed the amount the school budgets for this expense, that’s okay. You can still pay the full amount by using a qualified distribution from a Coverdell plan. It’s only for that off-campus housing (including fraternities and sororities) that you need to be careful.

Contributions into Section 529 Plans: The rules here are fairly straightforward and fairly stringent. If you take a distribution from a Coverdell ESA and contribute it into a 529 plan, the 529 plan needs to be for the same student. After this designation is made, you can’t change it; the student was the owner of the funds under Coverdell, so the student needs to remain the beneficiary of the funds under Section 529.

Contributions into Section 529 Plans: The rules here are fairly straightforward and fairly stringent. If you take a distribution from a Coverdell ESA and contribute it into a 529 plan, the 529 plan needs to be for the same student. After this designation is made, you can’t change it; the student was the owner of the funds under Coverdell, so the student needs to remain the beneficiary of the funds under Section 529.

Expenses for special-needs services that are required for special-needs students: Once again, the regulations in this area haven’t been finalized, so use your common sense. Don’t include orthopedic shoes for your flat-footed student, or contact lenses. It’s a safe bet that these aren’t covered under the regulations.

Expenses for special-needs services that are required for special-needs students: Once again, the regulations in this area haven’t been finalized, so use your common sense. Don’t include orthopedic shoes for your flat-footed student, or contact lenses. It’s a safe bet that these aren’t covered under the regulations.

The one rule that is apparent is that any services that are paid for by using a distribution from a Coverdell ESA needs to be required by an eligible educational institution.

.jpg)

Following investing rules and regulations

Coverdell ESAs generally follow the same investment rules and regulations as both traditional and Roth IRA accounts. Unlike 529 plans, there’s an awful lot that’s allowed, and not much that’s prohibited. Still, to keep everything kosher, you need to know what you can’t do and ways you can’t invest.

Your contributions need to be made in cash or cash equivalent.

Your contributions need to be made in cash or cash equivalent.

You may not purchase collectibles or life insurance with the money in your Coverdell ESA. You’re prohibited from buying insurance policies, artwork, household furnishings, antiques, metals, gems, stamps, or certain coins with that money, no matter how fine an investment it may appear to you. Specially minted U.S. gold and silver bullion coins and certain state-issued coins may be permitted. In addition, platinum coins and certain gold, silver, platinum, or palladium bullion are also allowed. If you’re interested in making this sort of investment with Coverdell funds, check Internal Revenue Code Section. 408(m)(3) to make sure that the coins or bullion you have in mind qualify.

You may not purchase collectibles or life insurance with the money in your Coverdell ESA. You’re prohibited from buying insurance policies, artwork, household furnishings, antiques, metals, gems, stamps, or certain coins with that money, no matter how fine an investment it may appear to you. Specially minted U.S. gold and silver bullion coins and certain state-issued coins may be permitted. In addition, platinum coins and certain gold, silver, platinum, or palladium bullion are also allowed. If you’re interested in making this sort of investment with Coverdell funds, check Internal Revenue Code Section. 408(m)(3) to make sure that the coins or bullion you have in mind qualify.

You may not commingle Coverdell account funds with any other funds. Your Coverdell account needs to be set up and accounted for completely separately from any of your other assets. The custodian or trustee, however, has the ability to commingle the money in your Coverdell account with money in other Coverdell accounts, creating what’s known as a “Common Trust Fund” or a “Common Investment Fund.” These funds work to your advantage because they allow the custodian or trustee to buy investments in larger pieces (which is less costly overall) and then split the pieces among all the accounts that contributed to the purchase.

You may not commingle Coverdell account funds with any other funds. Your Coverdell account needs to be set up and accounted for completely separately from any of your other assets. The custodian or trustee, however, has the ability to commingle the money in your Coverdell account with money in other Coverdell accounts, creating what’s known as a “Common Trust Fund” or a “Common Investment Fund.” These funds work to your advantage because they allow the custodian or trustee to buy investments in larger pieces (which is less costly overall) and then split the pieces among all the accounts that contributed to the purchase.

You may not pledge the value of a Coverdell ESA as collateral for any sort of loan. Not only are loans to you and your designated beneficiary prohibited, but so too are margin accounts, or brokerage accounts that allow you to borrow against the value of your stocks in order to either buy more stocks or take cash out of the account.

You may not pledge the value of a Coverdell ESA as collateral for any sort of loan. Not only are loans to you and your designated beneficiary prohibited, but so too are margin accounts, or brokerage accounts that allow you to borrow against the value of your stocks in order to either buy more stocks or take cash out of the account.

You may not take a loan from a Coverdell ESA, nor may your designated beneficiary. The money that’s in the account stays in the account until it’s time to make distributions to your beneficiary. Any money that comes out may only come out as a distribution. After it’s removed from the account, it may not be returned or repaid later.

You may not take a loan from a Coverdell ESA, nor may your designated beneficiary. The money that’s in the account stays in the account until it’s time to make distributions to your beneficiary. Any money that comes out may only come out as a distribution. After it’s removed from the account, it may not be returned or repaid later.

You may not pay yourself or anyone else for managing your student’s Coverdell ESA by using funds from the account. The only fees that may be charged against the account are the custodian’s or trustee’s. If you need to hire an investment advisor to help you select investments, you need to pay his fee out of your funds, not the account’s.

You may not pay yourself or anyone else for managing your student’s Coverdell ESA by using funds from the account. The only fees that may be charged against the account are the custodian’s or trustee’s. If you need to hire an investment advisor to help you select investments, you need to pay his fee out of your funds, not the account’s.

You may not sell or lease your property or your beneficiary’s property to a Coverdell account, nor may you make any other sort of asset exchange. The only thing that goes into the account is cash, and the only thing that should ever come out is cash, in the form of distributions to your beneficiary. Any other transaction is prohibited.

You may not sell or lease your property or your beneficiary’s property to a Coverdell account, nor may you make any other sort of asset exchange. The only thing that goes into the account is cash, and the only thing that should ever come out is cash, in the form of distributions to your beneficiary. Any other transaction is prohibited.

The custodian or trustee you choose to manage your Coverdell ESA may have other prohibitions in place. You may not be allowed to invest in real estate, for example, or trade in anything more complicated than ordinary stocks and bonds (as opposed to options, puts, calls, or the like). The custodian may also limit you to a certain group of mutual funds or their own certificates of deposit. Investigate what limitations the custodian has in place before you open your account, and make sure that you can live within those rules.

.jpg)

Making Account Contributions

You or anyone else in your family or circle of friends, including the student for whom the account has been established, may contribute to a Coverdell ESA, provided that you qualify under the income phaseout rules (see the section “Looking at income phaseouts for contributors,” later in this chapter). Even your employer or a charitable organization may contribute (and in these cases, the $2,000 annual limit on contributions for the benefit of a specific beneficiary, which is explained in detail in the section “Spelling out contribution limits,” doesn’t apply).

When making a contribution into a Coverdell account, keep the following in mind:

Contributions must be made in cash. Checks, money orders, and so forth are okay, too, but stocks, bonds, life insurance policies, real estate, and trading stamps are not.

Contributions must be made in cash. Checks, money orders, and so forth are okay, too, but stocks, bonds, life insurance policies, real estate, and trading stamps are not.

Contributions can’t be made into an account for the benefit of a beneficiary who’s 18 years or older, except if that beneficiary falls under the special-needs category. After your beneficiary hits that magic age, you must stop putting money into his Coverdell account unless you’re absolutely certain that your student will qualify under the special-needs rules, in which case no age cutoff exists.

Contributions can’t be made into an account for the benefit of a beneficiary who’s 18 years or older, except if that beneficiary falls under the special-needs category. After your beneficiary hits that magic age, you must stop putting money into his Coverdell account unless you’re absolutely certain that your student will qualify under the special-needs rules, in which case no age cutoff exists.

Contributions for a particular year must be made by the original filing deadline for your tax returns for that year. Don’t plan on making your contribution on October 15 of the following year because your income tax returns are on extension — original filing deadline means April 15 for calendar year taxpayers.

Contributions for a particular year must be made by the original filing deadline for your tax returns for that year. Don’t plan on making your contribution on October 15 of the following year because your income tax returns are on extension — original filing deadline means April 15 for calendar year taxpayers.

Spelling out contribution limits

Before 2002, contributions into the old Education IRA’s were limited to $500 per student per year, subject to some phaseout rules (see the section “Looking at income phaseouts for contributors,” later in this chapter, for more info). In addition, if you made a contribution to an Education IRA in a given year for a given student, you couldn’t also make a contribution to a Section 529 plan. As a result of these low contribution limits, most people didn’t bother to fund these accounts, and even if they did, it probably never amounted to much. The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, which changed Education IRA’s to Coverdell ESAs, greatly expanded the number of people who were willing to contribute and the amount that could be given.

Today, although the amount that can be contributed is much greater, there are still contribution limits, and you have to keep track of them. You need to know not only how much you’re putting into any one beneficiary’s account but also how much other people may be putting into either that account, or other accounts, for the same beneficiary.

Aggregate annual contributions, per beneficiary

For example, Harvey and Cynthia have one child for whom they’ve set up a Coverdell ESA. In 2002, they contributed $2,000 to this account. They plan to do the same in 2003, but much to their surprise, they find that Harvey’s brother has put his $500 birthday gift for his nephew into the account in 2003 (he’s a pretty generous uncle). In 2003, then, Harvey and Cynthia may put only $1,500 into the Coverdell account they established, in order to not exceed the maximum contribution per beneficiary of $2,000 annually.

As this example shows, your contributions aren’t limited only to plans that you set up; you may make payments into any plan established for a particular beneficiary.

Annual contributions per contributor

For example, Harvey and Cynthia now have four children (they’ve added a set of triplets). They may establish Coverdell ESAs for each of their children. In each year in which they meet the income phaseout requirements, they may contribute up to $2,000 into an account for each of their children (as long as their children are under age 18), or a total of $8,000 annually ($2,000 x 4). Should Harvey’s generous brother decide to contribute his birthday gifts into the kids’ Coverdell accounts rather than giving the money to his nieces and nephews outright, the amount that Harvey and Cynthia may contribute will be reduced by the amount of that gift.

Gift tax and Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax consequences

Unlike gifts in Section 529 plans, which may be quite large and often trigger Gift and Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax (GSTT) consequences on their own, gifts into Coverdell ESAs will never, by themselves, create a situation where you need to fill out a Form 709. The limit on the size of the annual contribution per beneficiary prohibits this, as $2,000 will never begin to approach the $11,000 annual exclusion amount currently available to every donor for every donee.

So suppose that Harvey and Cynthia add twins to their family (they’re up to six children, and they may want to remember that they may need to put all these children through college). They can have a Coverdell ESA for each of the six, contribute the full $2,000 to each account every year, and never need to file a gift tax return even though they’re gifting away a total of $12,000 every year. However, they also have a Section 529 plan for each child, into which they’re putting $10,000 each year per child. Now, their total gift to or for the benefit of each child is $12,000 per year, and a gift tax return is required, as their annual exclusion amount per donee is only $11,000.

Looking at income phaseouts for contributors

Anyone can make a contribution into a Section 529 plan, regardless of how much income he or she earns. This isn’t the case for Coverdell ESAs; income really matters here. If you earn too much, you may be dumb out of luck in any given year and may have to wait to make contributions into your students’ accounts only in the years in which your income falls below the limits.

The income phaseout range for single taxpayers is $95,000 to $110,000, based on your modified adjusted gross income, described later in this section, and the range for married taxpayers is $190,000 to $220,000, or exactly double that of single taxpayers. Here’s how the phaseout system works:

If you’re below the bottom of the phaseout range, you may contribute the full $2,000 per beneficiary.

If you’re below the bottom of the phaseout range, you may contribute the full $2,000 per beneficiary.

If you’re within the phaseout range, your contribution will be limited according to a formula.

If you’re within the phaseout range, your contribution will be limited according to a formula.

If you’re above the phaseout range, you may not make any contributions in the current year.

If you’re above the phaseout range, you may not make any contributions in the current year.

For the purpose of determining whether you may, or may not, contribute, you need to calculate your modified adjusted gross income, which adds the following items to your adjusted gross income from your tax return (from the line labeled “Adjusted Gross Income”):

Your foreign earned income exclusion

Your foreign earned income exclusion

Your foreign housing exclusion

Your foreign housing exclusion

If you’re a bona fide resident of American Samoa, your excluded income

If you’re a bona fide resident of American Samoa, your excluded income

Any excluded income from Puerto Rico

Any excluded income from Puerto Rico

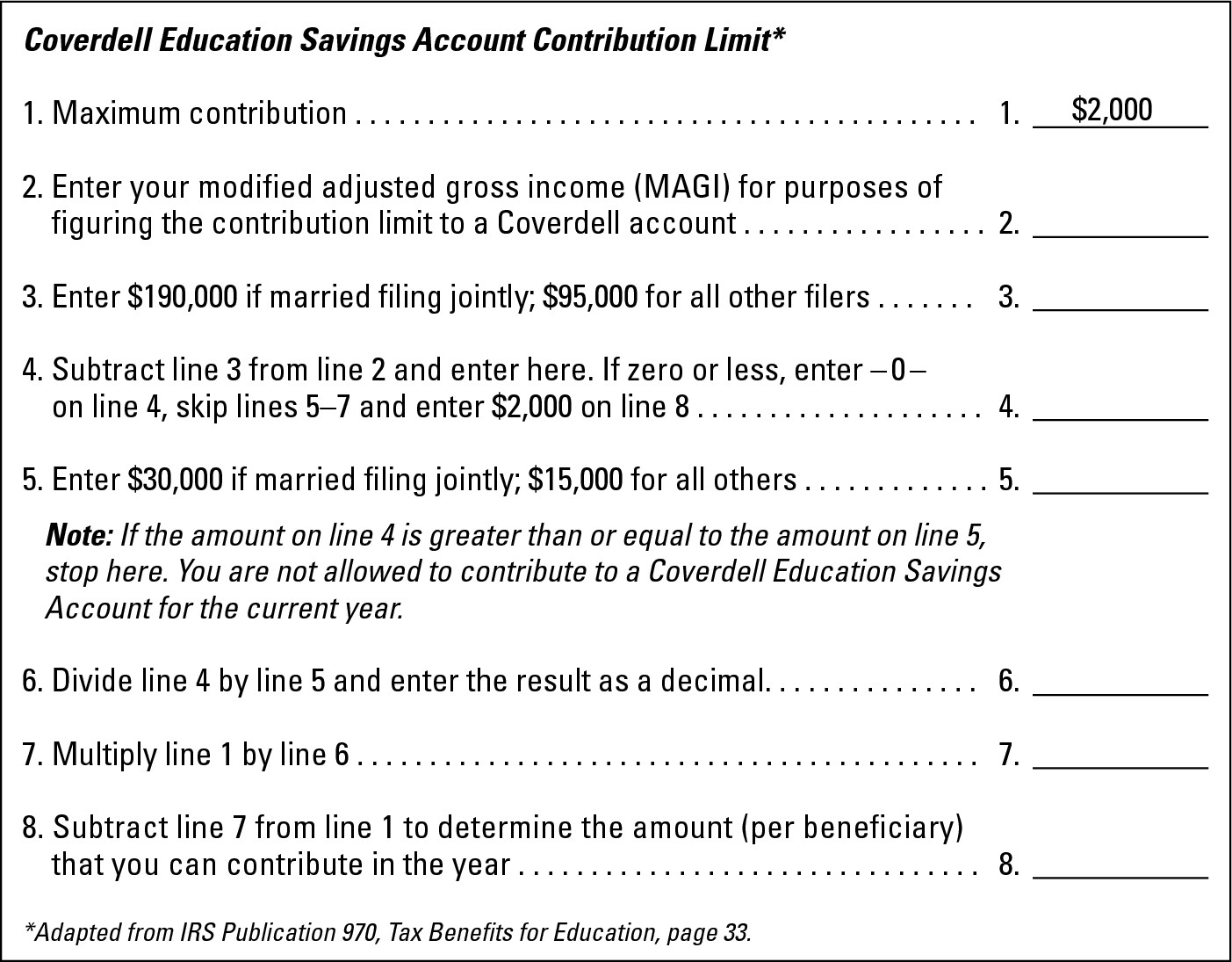

After you arrive at your modified adjusted gross income, you then can determine whether you can contribute at all or if your contribution will be limited. If you find that you fall within the phaseout range, you may calculate your limited contribution, using Figure 8-1 as an example.

|

Figure 8-1: Worksheet to figure out limited contribution to a Coverdell account. |

|

Getting rid of excess contributions

Because of the limits on contributions, you’ve probably already deduced that, when you give more than the maximum allowed, you’re going to have your hand slapped. In fact, it’s quite a hand slap — the penalty for making excess contributions is a 6 percent excise tax on the overage (contribution amounts plus any earnings attributable to those contributions) for each year that it remains in the account.

Despite your best planning and plotting, excess contributions do happen. You may have put money into your kids’ accounts at the beginning of the year and then gone on to earn much more money than you anticipated. Or you could’ve contributed the maximum amount, unaware that Grandma was also funding an account she had set up for your student. Excess contributions happen for any number of reasons; the important fact to know is that they can be corrected.

Once your student receives his contribution information from the account custodian or trustee on Form 5498 each year, you can determine whether more than the maximum $2,000 has been contributed in a particular year for that child. If it has been, then you have three ways to deal with the problem:

Withdraw the excess cash

Withdraw the excess cash

Pay the 6 percent excise tax

Pay the 6 percent excise tax

Absorb the excess contributions in future years by not making additional contributions

Absorb the excess contributions in future years by not making additional contributions

Withdrawing the excess

When you discover that too much money has been put into a Coverdell account or accounts for your child, the easiest solution is to withdraw the excess contribution (plus any earnings that have accrued on that amount) before the due date of the student’s tax return. There will be no excise tax on the excess, but the student is responsible for paying the income tax (but no 10 percent penalty) on the income earned for the period of time the extra money stays in his account.

.jpg)

Paying the excise tax

Suppose that you fail to notice that you’ve put too much money into your student’s account, or you don’t manage to correct the problem in time (before your student’s tax return filing deadline). As a result, for the year following the year of the excess contribution and for all subsequent years until the problem is resolved, your beneficiary will have to pay an additional 6 percent excise tax on all excess amounts each year that they remain in the account. At any time along the way, you can fix this by withdrawing the overage from the account; in the year the funds are withdrawn, your student will pay the income tax only on the income earned by the excess.

Absorbing excess contributions

Finally, you may find that the problem eventually disappears all by itself. If your designated beneficiary is under age 18, you may choose to stop making contributions into his account, and instead each year assign up to the maximum $2,000 contribution amount (depending on where your income falls in the phaseout rules) from the excess until the excess has disappeared. For example, Susan’s Coverdell ESA currently has $6,000 in excess contributions. Because Susan is only 8 years old, her parents, whose combined income falls well below the phaseout amounts, choose to assign $2,000 from the excess in each of the following three years instead of making additional contributions into Susan’s account. In the first year, Susan will pay a 6 percent excise tax on the full $6,000. In year two, she’ll pay an excise tax only on $4,000; in year three, $2,000; and in year four, when Susan is 10 years old, she’ll no longer pay any excise tax. Beginning in the following year, provided her parents continue to earn less than the phaseout amount, they may again begin to contribute a maximum of $2,000 per year.

Taking Distributions

The point of having a Coverdell ESA is to enable you to pay for some or all of your student’s qualified educational expenses with a combination of money you’ve saved (on which you previously paid income tax) and the earnings on your savings, on which you’ve paid no tax.

What you may not realize is that you are not actually the one making the payments for these expenses; your student is when using distributions from a Coverdell ESA. When distributions are made from a Coverdell account, the IRS considers them made to the student (even if checks are written directly to an educational institution), and the student bears the financial consequences.

If distributions are made for qualified expenses before December 31, 2010 (and if Congress takes no action on extending or making the current provisions permanent), your student won’t pay any tax. If a distribution is made for a nonqualified expense (for example, he used money to buy a computer for college, even though it wasn’t a requirement of his course), then tax needs to be paid on the income portion only. A 10 percent penalty will probably also be applied, for good measure.

.jpg)

If your student takes a taxable distribution from a Coverdell account, the 10 percent penalty will be waived under the following circumstances:

A taxable distribution is made on account of the death of the designated beneficiary, either to the beneficiary or to his or her estate.

A taxable distribution is made on account of the death of the designated beneficiary, either to the beneficiary or to his or her estate.

A taxable distribution is made when it’s used for nonqualified expenses, but the expenses are incurred due to the disability of the designated beneficiary. You must attach a doctor’s statement to your beneficiary’s tax return, indicating the type of disability and the expected duration or whether it’s expected to result in death.

A taxable distribution is made when it’s used for nonqualified expenses, but the expenses are incurred due to the disability of the designated beneficiary. You must attach a doctor’s statement to your beneficiary’s tax return, indicating the type of disability and the expected duration or whether it’s expected to result in death.

A taxable distribution is made in excess of qualified educational expenses because those expenses were reduced by the receipt of nontaxable educational assistance. For example, Joan has qualified educational expenses of $10,000, takes a $10,000 distribution from her Coverdell account to pay for those expenses, and then finds that she also is receiving a tax-free scholarship for $5,000 from her school. In this case, only $5,000 of the Coverdell distribution is being used to pay for qualified educational expenses. Because Joan’s qualifying expenses were reduced by the $5,000 scholarship, the income portion of the remaining $5,000 Coverdell distribution is subject only to income tax, and not an additional 10 percent penalty.

A taxable distribution is made in excess of qualified educational expenses because those expenses were reduced by the receipt of nontaxable educational assistance. For example, Joan has qualified educational expenses of $10,000, takes a $10,000 distribution from her Coverdell account to pay for those expenses, and then finds that she also is receiving a tax-free scholarship for $5,000 from her school. In this case, only $5,000 of the Coverdell distribution is being used to pay for qualified educational expenses. Because Joan’s qualifying expenses were reduced by the $5,000 scholarship, the income portion of the remaining $5,000 Coverdell distribution is subject only to income tax, and not an additional 10 percent penalty.

A taxable distribution occurs only because qualified educational expenses were used to enable the taxpayer to take the Hope or Lifetime Learning Credit.

A taxable distribution occurs only because qualified educational expenses were used to enable the taxpayer to take the Hope or Lifetime Learning Credit.

A taxable distribution occurs because excess contributions given in the current tax year are returned to the designated beneficiary before he files his tax return for that year.

A taxable distribution occurs because excess contributions given in the current tax year are returned to the designated beneficiary before he files his tax return for that year.

Transferring Accounts and Changing Account Beneficiaries

Just as in a Section 529 plan, you save in a Coverdell ESA for a day in the future: the day your child attends an educational institution that has some real dollar costs attached to it. Of course, for some, this day never arrives, and the money languishes in the account until the magic mandatory distribution to the designated beneficiary at age 30. For some, this may not be such a bad thing — you may feel that you saved the money for this particular person, and by the time that person has reached age 30, she is mature enough to manage the funds herself.

If you don’t belong to that specific group and the thought of handing over all that money to that particular beneficiary sticks in your craw, you may want to explore whether you can change to a new designated beneficiary, taking the old one right out of the equation.

The designated beneficiary of a Coverdell ESA is the deemed owner of the assets in the account; however, he or she may not be the person named in the initial account-opening documents as being responsible for making the decisions regarding the account. If you’re the named responsible adult, you’re in luck, and you can initiate the transfer.

.jpg)

Qualifying relationships for successor- designated beneficiaries

In setting up a Coverdell account for your original beneficiary, you transfer all right, title, and interest in the money you gift into the account. Now, as the responsible adult named on the account, you’re proposing taking that money away from your beneficiary. If you could do that without restriction, that would mean that you retained real control over the money. You don’t, so you can’t transfer to a new beneficiary without following the rules.

And the rules are quite simple. The new beneficiary must be related to the original beneficiary (not to you) in one of the following ways:

A lineal descendent, such as a child, grandchild, or stepchild

A lineal descendent, such as a child, grandchild, or stepchild

A lineal ancestor, including the beneficiary’s mother, father, grandmother, grandfather, stepmother, or stepfather

A lineal ancestor, including the beneficiary’s mother, father, grandmother, grandfather, stepmother, or stepfather

A brother, sister, stepbrother, or stepsister of the original beneficiary

A brother, sister, stepbrother, or stepsister of the original beneficiary

A niece or nephew (but no stepniece or stepnephew)

A niece or nephew (but no stepniece or stepnephew)

An aunt, uncle, or first cousin of the original beneficiary (but no step- aunts, uncles, or cousins)

An aunt, uncle, or first cousin of the original beneficiary (but no step- aunts, uncles, or cousins)

A mother-in-law, father-in-law, sister-in-law, brother-in-law, daughter-in-law, or son-in-law

A mother-in-law, father-in-law, sister-in-law, brother-in-law, daughter-in-law, or son-in-law

The spouse of any of the people listed above, or of the original beneficiary

The spouse of any of the people listed above, or of the original beneficiary

Maximum age of the successor beneficiary

All assets in Coverdell ESAs need to be totally distributed once the designated beneficiary reaches age 30. However, you do have the option of transferring the balance of the account to a new beneficiary just before that date, keeping the account open and operating well beyond the 30th birthday of the original designated beneficiary. So long as the new beneficiary is under 30 and falls within the acceptable range of family relationship to the original beneficiary, you can effect the transfer. If you choose a new beneficiary who is under age 18, you may even begin to make contributions into the account again.

Here’s how it works: You begin to fund a Coverdell account for the first designated beneficiary, and continue making contributions until you’re forced to stop when she reaches age 18. Suppose that this beneficiary then receives a full-paid scholarship and she doesn’t need the funds, but you have another child, or even grandchild, who might benefit from the money you’ve saved. Instead of waiting and distributing the entire amount to the original designated beneficiary when she’s 30, you choose to change beneficiaries and go with the younger child. Until that child reaches 18, you may make contributions into the account to the extent allowable by the governing rules.

Additional transfers of this nature can continue to be made using the same account, so long as the new beneficiary always is under 30 years old and is related to the original beneficiary in the manner described in the section “Qualifying relationships for successor-designated beneficiaries,” earlier in this chapter. Whoever is the beneficiary when the account makes distributions is the person who pays income tax on the earnings, if any tax needs to be paid. Whoever is the beneficiary when excess contributions are inside the account is the one who must pay the excise tax on the excess contributions. And whoever is the beneficiary when the account finally terminates is the one who receives the final distribution and pays income tax on whatever income remains inside the account.

Rolling over Coverdell accounts

In addition to changing the designated beneficiary on an account, if you’re the responsible adult on an account, you may also choose to move from one Coverdell account to another, either for the same beneficiary or for a new one (but one who fulfills all the requirements listed in the section “Qualifying relationships for successor-designated beneficiaries,” earlier in this chapter).

.jpg)

Transferring into a Section 529 plan

Although you’re limited by beneficiary age within a Coverdell account, Section 529 plans have no age limitations. Accordingly, you may want to make a tax-free transfer from the Coverdell account into a Section 529 plan for the same designated beneficiary before that beneficiary turns age 30. Transferring from a Coverdell account to a Section 529 plan gives rise to some interesting consequences, though, so you want to be careful.

If giving Baby Alex control over a Section 529 plan gives you the heebie-jeebies, consider making a contribution directly into a 529 plan, using an equivalent amount of your funds rather than the proceeds from the Coverdell account. You must deposit your funds within 60 days after making the withdrawal from the Coverdell account. By funding the 529 plan with your own funds, you retain control over the 529 plan as the account owner; you’ve also fulfilled the rollover requirement of completing the transfer within 60 days. The proceeds from the Coverdell withdrawal now belong to your designated beneficiary (over whose assets you still have control until he or she reaches age 18), and the new 529 assets remain under your control.

Neither scenario is perfect, in that they allow control over money to pass to your designated beneficiary, either by making her the account owner on a Section 529 plan or by actually handing her the cash. Still, if the amounts are not huge or if your designated beneficiary is incredibly mature for her age, it may work for you.

Transferring due to divorce

When planning for your student’s education, you’re probably not imagining a time when your designated beneficiary will be old enough to think about any marital issues, especially a marital dissolution. After all, you probably set up this account when your child was just a kid, and the first thought that crosses your mind when you check on him asleep in his bed is not how he’s going to divide his assets when he gets a divorce.

Still, a Coverdell ESA can live on well into adulthood, and it may still be an asset owned by your designated beneficiary after he marries, and even at the time of a divorce. If this happens to your student, there are some things you both should know:

Coverdell ESAs aren’t counted as community property in community property states. Funds are gifted directly to the owner of the account (even if the gifts occur after marriage through a tax-free rollover from a different Coverdell ESA) and are maintained solely for the benefit of the account owner.

Coverdell ESAs aren’t counted as community property in community property states. Funds are gifted directly to the owner of the account (even if the gifts occur after marriage through a tax-free rollover from a different Coverdell ESA) and are maintained solely for the benefit of the account owner.

The owner of the account may include a Coverdell ESA as part of the divorce or separation agreement, transferring ownership to his or her spouse or former spouse. In this case, provided the new owner is under age 30, this is a tax-free transfer, even if another tax-free transfer or rollover occurred within the last 12 months.

The owner of the account may include a Coverdell ESA as part of the divorce or separation agreement, transferring ownership to his or her spouse or former spouse. In this case, provided the new owner is under age 30, this is a tax-free transfer, even if another tax-free transfer or rollover occurred within the last 12 months.