Some Issues Concerning the Nature of Economic Explanation

There is a long and substantial body of literature in philosophy and philosophy of science about the nature of explanation. Those issues likewise show up in economics in various guises, though often not explicitly stated and discussed. In what follows I first outline some general issues about explanation and state what I take to be some general morals. I then look at various practices and disputes in economics, outline where the issues of explanation come up, and try to determine which claims are plausible which are not. Section 1 provides the background. Section II looks at attempts to provide purely formal accounts of explanation in economics. Section III looks at arguments given that economics does not seek explanations in terms of unobservables. Section IV looks at issues surrounding macro vs micro explanation. Section V discusses how models can explain while being unrealistic. Section VI looks at functional and selectionist explanations, especially evolutionary game theory. Section VII looks at some ontological assumptions about causation raised by standard regression models in economics.

1 Some Controversies About Explanation

Work on explanation in philosophy of science is one area where progress has been made, albeit much of it negative. The nomological deductive model of explanation was dominant up through the sixties. It equated explanations with deductions of a description of the phenomena to be explained from premises essentially including scientific laws. There was some (and still is) controversy about what a scientific law involves, but generally speaking laws were thought to be nonaccidental generalizations that made no reference to particulars and supported counterfactual claims. Deriving Kepler’s laws from Newton’s laws of motion was a successful explanation; deriving the claim that I found a penny in my pocket from the generalization “all the coins in my pocket are pennies” is not a successful explanation. The latter, unlike the former, involves an accidental generalization about a particular that would not support counterfactuals.

This view was eventually rejected on multiple grounds, some more radical than others. The more moderate criticism was that derivation from a law was neither necessary nor sufficient to explain because clear counterexamples could be generated. All men who take birth control pills do not get pregnant and so John who takes such pills did not get pregnant. There is derivation from a law, but the law is irrelevant. John also has now has paresis, which we can explain as resulting from his syphilis (and, earlier in the causal chain, to his mistaken belief that birth control pills prevent STDs), although we do not have a law on the books that subsumes the event in question. Not surprising, there have been multiple attempts to revise the account to get around these problems, which in turn led to a new round of counterexamples.

A related set of criticisms concerned distinguishing the scientific laws from the nonscientific. No reference to particulars as a criterion is doubtful because it is merely syntactic. References to a particular can be turned into references to predicate. So if the laws of evolution seem to refer to a particular-this planet we can take them to be about “Darwinian systems.” Some apparent accidental generalizations can support counterfactuals. If my pockets are designed such that only pennies can put in them, then if were try to place a quarter in them, I would fail. Again, various attempts to refine away such counterexamples resulted.

The more radical criticism came from the broad postpositivist movement in science. There are various ways to formulate its core commitments, but in rough terms they are a form of naturalism which holds that philosophy of science had to be sensitive to what scientists actually do. Taken seriously, this means rejecting conceptual analysis tested on philosophers intuitions as the final arbiter and thus giving up on Hempel’s project. The goal then is to better understand how science works. With that as the goal, numerous historical, sociological and rational reconstructive accounts of the practice of explanation in science emerged. They extended the counterexamples: much of science explains in ways that are not well captured by deriving from laws.

Some general results followed. One was that explanation is often about citing of causes. Causes had been excluded by the positivist minded as too metaphysical, but scientists certainly seemed to talk of causes, at least those — like economists — not already in the grips of the dogma at issue. John’s calamities have a natural causal explanation that grounds our sense that the derivation from laws is neither sufficient nor necessary. The citing of causes becomes a paradigm of explanation.

There have been some attempts to take the science seriously but to leave out the causation. The most developed tries to account for explanation in terms of unification. My suspicion is that such accounts are Hempel’s project in new clothes. Derivation and other formal criterion are claimed to be the essence of explanation. While the goal of unification certainly is part of the practice of science and worthy of investigation, I doubt that there is any useful claim of the form “x explains if and only if x is unified in such and such a way.” The most developed account is that of Kitcher [1989], who takes explanation to come from instantiating an argument pattern or schema, where Darwinian selectionist explanations are his prime examples.

A number of doubts about Kitcher’s account have been raised [Kincaid, 1996]. Kitcher distinguishes multiple argument patterns in biology, for example, simple selection, directional selection, and so on. How do we determine that these are separate patterns rather than one more complex one? When is one pattern simpler than another? How do we weigh the scope of the pattern against its simplicity, something Kitcher’s account requires us to do? What makes these decision an objective matter rather than simply a subjective sense of “seeing things fit together”? And why should we expect that there should be simple patterns in the first place? Don’t the social and biological sciences show a diversity of processes, so that we can ask the same question that has been asked about simplicity — why think unified theories are better? Finally, it is quite clear that we can think of unification as a good thing for reasons unconnected to explanation—finding interconnections increases the possibilities for triangulation and boot strap testing, for example.

More careful and detailed looks at scientific practice led to the recognition that context plays an essential part in many explanations and that it is sometimes useful to think of explanations as the answers to specific kinds of questions [Garfinkel, 1981]. Questions and their answers have an inevitable contextual component. If I ask “why did Adam eat the apple?” the question is ambiguous until I specify the relevant contrast classes. Do I want to know why Adam rather then Eve ate the apple? Do I want to know what Adam ate the apple rather than throwing it? And so on. Furthermore, the background knowledge of scientists seeking explanations dictates what general kind of information is relevant. So, for example, in physics before the rise of quantum mechanics, no answer that involved action at a distance would be considered relevant. Keeping clear about these contextual elements allow for a more nuanced approach to explanation and we will see below that it can help dissolve some standard confusions.

One important implication of the above developments is that assessing explanations is unlikely to be a purely formal process. By a formal process I mean ones that rely on only logical properties rather than on substantive domain specific information (R squared is often thought to be a purely formal measure as we will see below). Given that the paradigm case of explanation is the citing of causes and that explanation involves context, we should expect that evaluating explanations requires a detailed argument invoking domain specific assumptions. Many different kinds of causes can be invoked: distal, structural, necessary, sufficient, important, and so on. Moreover, when identifying causes, decisions have to be made and justified about what to take as part of the causal field — the causal factors that are treated as background and irrelevant. Combining such variations will be part of the process of setting the contrast class and relevance relation as determined by the interests of those seeking explanations. We will see later that spelling out such complete set of elements in an explanation can sometimes clarify controversies over explanation in economics.

2 Formal Criteria for Explanation in Economics

The lure of formal criteria for explanatory success is still strong in contemporary economics. I want to look at two general instances which are fairly common in contemporary economics — the notion that explanation comes from providing a set of equations and that explanatory power is measured by the amount of explained variance, or R squared.

The nomonological deductive model of explanation still carries enormous weight within economics. This is obvious from a core practice of the profession: taking a set of equations as necessary and sufficient for producing an explanatory model. The equations of a given model are supposed to be the universal regularities that a nomological deductive explanation needs. The set of equations is used to show that the phenomena of interest can be derived from the model. There is of course sometimes a causal story lurking in the background, and the commonly used phrases “is a function of,” “is associated with,” and “is determined by” can have causal overtones. But the causal interpretation is usually in the background if present at all. Moreover, when it comes to testing the model, the causal interpretation frequently drops out altogether as regression equations are estimated without much pretense of showing causality.

Let me cite one example to illustrate my point — various models from growth theory.1 The seminal Solow [1956] model dates from the mid 1950s and versions of it have dominated neoclassical thinking about growth and development. Output is determined by an aggregate production function that makes output a function of the supply of capital and labor, where the size of the latter is determined by an exogenously given level of technology. The size of the capital stock is determined by the savings, population growth, depreciation, and technological growth rates, all of which are taken as exogenous.

There are two crucial implications of this model for development. First increases in savings and capital investments are central for growth and second, economies will converge toward a steady state where growth is constant. The level of growth in the steady state depends only on the exogenously given technological change.

However, the original Solow model had some unwelcome consequences. Among others it implies that new investment in the underdeveloped countries should have a much higher rate of return and thus we should see very heavy investment from the developed countries. That is not what the evidence shows.

This has resulted in what is called an “augmented Solow model” [Mankiew, 1995].

The augmented Solow model results from seeing that the unwanted predictions depend crucially on the relative share of capital. A higher share of capital implies greater effects on income of savings and that return to capital varies less with income. But if we add to the Solow model another capital variable — for human capital — we get a change of the relative share of capital (physical and human) and thus the troubling predictions go away. Since human capital theory was a major innovation in the period after Solow’s account was proposed, this is a natural emendation.

Mankiew’s model still leaves technological change exogenous. So further development has worked to make it endogenous. In Romer’s [1990; 1994] models, on which I focus here, technological change becomes explained in that there is a knowledge producing sector that takes physical and human capital and existing knowledge as inputs and produces technological designs as output. This sector also introduces economies of scale and drops perfect competition in that part of the knowledge produced is proprietary and produced by monopolies and that part of the knowledge produced becomes a public good. So we have the promise of explaining technological progress and doing so with a more realistic model that breaks with some general equilibrium theory simplifications found in the augmented Solow model.

Finally, further developments tried to bring in social factors such as the rule of law. Barro [2001] is perhaps the best known advocate of this approach and he uses cross country regressions to test versions of the most extensive model that incorporates all the factors added to the original Solow model. Thus the final instantiation tested by Barro is described by the equation:

where Y is GDP, K and L are capital and labor, s and n are savings rate and population size, H is investment in human capital, and I is set of institutional factors—rule of law, property rights, size of government, etc

What implicit assumptions about explanation does this body of work make? Its explanations come by showing that there are functional relations between variables — in short, universal regularities. Moreover, these models are committed to universal regularities in a very strong sense in that the assumption is that there is one production function which describes all economies.

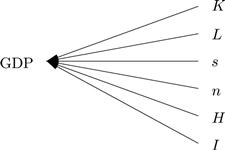

Is growth theory then committed to a nomological-deductive model of explanation? The language used to describe these models is ambiguous in that there are clearly times when the implication is that there are more than universal regularities involved-the models are describing the causes of growth. However, there is no attempt here to develop an explicit causal model using structural equations that specify the details of the causal process. By the time this work is crystalized in Barro’s empirical work, the implicit causal model is the simple shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Causal model of cross country growth regressions

Obviously this is an entirely implausible causal model, for there is good reason to think there are causal influences from the independent variable GDP to the dependent variables and causal relations among the latter. So the causal model is really only gestured to and the real explanatory work is being done by the universal regularities. These explanations are thus through and through nomological deductive and thus perhaps suspect for that reason.

I have used growth theory to show that nomological-deductive models still hold sway in economics. Perhaps growth theory is unique in this regard? I do not think it is. The practice of writing down a set of equations without a causal interpretation and using that model to explain is standard fare in mainstream economics.

There is one route to defending this practice that has not been explicitly advanced in the case of economics but that is worth exploring. It turns on issues about dynamical systems. The argument is this: We may know that deduction from laws seems neither necessary nor sufficient for explanation, but our naturalist stance requires us to take scientific practice seriously, and surely deduction from laws is sometimes a crucial part of how scientists explain. To be more specific, a standard scientific practice is to identify a set of differential equations that suffice to trace the movement of variables through state space. When they have found models that can successfully do so, they claim to have explained the dynamics of the system. So if economists can do the same, then we have only bad a priori reasons to deny that they are explaining.

Applied to growth theory, the argument would then be that its practitioners are doing something similar, viz. trying to describe the value of GDP over time as a function of a key set of variables. If the available data are consistent with the growth models, they then have explained even if there is no plausible causal model being tested.

I am skeptical of this defense. It leaves economics without much policy relevance since we are explicitly eschewing causal notions. Also, if I claim that that my model of movement through state space allows me to tell governments what variables to manipulate, then I am claiming that intervening on a variable will lead to changes in GDP and I have invoked a classic conception of causality, viz, that an intervention on one factor produces a change in another (see [Woodward, 1997]).

Let me turn now to the other formalist notion of explanation common in economics (and elsewhere). It is standard practice to claim that one model has more explanatory power than another if it has a higher R squared. R squared is measure of goodness of it of data about a line showing the relation between changes in two or more variables. The closer the cloud of data the line, the greater the explained variance. This is a formal criterion in that it can be determined by calculation alone.

While appeal to R squared is a common rhetorical device, it is a very tenuous connection to any plausible explanatory virtues for many reasons.2 Either it is meant to be merely a measure of predictability in a given data set or it is a measure of causal influence. In either case it does not tell us much about explanatory power. Taken as a measure of predictive power, it is limited in that it predicts variances only. But what we mostly want to predict is levels, about which it is silent. In fact, two models can have exactly the same R squared and yet describe regression lines with very different slopes, the natural predictive measure of levels. Furthermore even in predicting variance, it is entirely dependent on the variance in the sample — if a covariate shows no variation, then it cannot predict anything. This leads to getting very different measures of explanatory power across samples for reasons not having any obvious connection to explanation.

Taken as a measure of causal explanatory power, R squared does not fare any better. The problem of explaining variances rather than levels shows up here as well—if it measures causal influence, it has to be influences on variances. But we often do not care about the causes of variance in economic variables but instead about the causes of levels of those variables about which it is silent. Similarly, because the size of R squared varies with variance in the sample, it can find a large effect in one sample and none in another for arbitrary, noncausal reasons. So while there may be some useful epistemic roles for R squared, measuring explanatory power is not one of them.

3 Theoretical Entities and Explanation

There have been long standing debates in the philosophy of science about the place of theoretical posits in science, most around epistemological issues concerning how belief in them is warranted. A related but distinct question that has been raised about economics is the extent to which economic theory is about unobservables. It has been argued by Mäki [2002] and Hausman [1998] that economics largely is unconcerned with theoretical nonobservational entities. Both, reasonably enough, note that the observable/nonobservable distinction can be drawn in various ways and that its epistemic importance is questionable. However, both think the entities postulated by economics are on the par with ordinary relative observables like tables and chairs — they are, in Mäki’s terminology, commonsensibles. Mäki argues that unobservable entities are no major concern for social scientists. They are of no major concern because the posits of social theories are continuous with the common sense realm, and social scientists, as social actors themselves, have access to this realm. Hausman affirms the claim that most standard entities invoked by economics, e.g. expected utilities, are extrapolations from ordinary common sense notions such as belief and desire and adds that when they are not — such as Marxian labor values — they have turned out not to be important in economics.

Several lessons from postKuhnian naturalist philosophy of science are relevant here:

1. Scientific theories are not always unified, monolithic entities and they are not the whole of science. From Kuhn [1962], work in the history and sociology of science [Beller, 1999], arguments developed by advocates of the semantic view of theories [Giere, 1988], and work on the role of models in science by Cartwright [1999], we have good reason to believe that “theories” have diverse interpretations across individuals and applications, are often not a single axiomatizable set of statements, and involve differing kinds of extratheoretical assumptions and devices in the process of explaining.

2. Our knowledge of the world is not divided into natural kinds such that we can evaluate the epistemic status of their tokens all at once and such that some kinds of knowledge have automatic epistemic privilege over others. These points are relevant because they should make us suspicious of quick pronouncement about what economics is about and of claims that there are certain kinds of knowledge — in this case “commonsensibles” — that share a common epistemic fate.

I would thus defend the view that there is no short story of what economics is about and in that telling the longer story we would find that it is often not about “commonsensibles” at all. No doubt, given the holism of meaning, our common sense economic concepts have some connection to the terms in which economic theory explains. Yet that connection is not enough, because the claim is that objects and processes described by economic theory are familiar everyday objects much like tables and chairs. I think economics traffics in objects and processes that have an everyday counterpart but themselves are not commonsensibles at all as well as objects and process that have no everyday counterpart, though the two kinds of case are bound to be arbitrary in some cases because what objects exist and what properties they have are interrelated.

An example from the first category is explaining price changes as due to changes in demand. Of course we take price and demand changes as occurrences observed in everyday life. However, the common sense observed notion of demand—“there is a big line at the gas station” — is worlds apart from the “demand” notion that is refined by theory into shifts in demand curves and moves along the curve, not to mention the full details defined by a Slutsky matrix. It is a truism in economics that these notions of demand are very difficult to observe because their component elements are hard to identify. It is very hard to see how it is that we have knowledge of them of the sort we have of tables and chairs. Hausman’s claim that apparently unobservable aggregate quantities are really just averages of observable quantities seems mistaken in this fundamental case.

An example from the second category are the various equilibrium concepts in game theory. We explain the behavior of oligopolies as the result of strategies in some kind of equilibrium in some kind of game. A subgame perfect Bayesian equilibrium of a two stage Cournot game seems rather far from any common sense object we observe. In fact, a fundamental problem in industrial organization is to find any way to tie this entity to anything observable at all [Sutton, 1998]. There certainly seem to be unobservables in economics.

4 When do Models Explain?

The fact that economics is bound to posit entities and processes that are unobservable is closely connected to another standard issue in economic methodology, namely, how can models with false assumptions explain? Note that this is distinct from the question how we can have good evidence for models with false assumptions, though of course there are interconnections. It is the question about explanation that I turn to in this section.

One route to showing that unrealistic models in economics can explain is in effect to deny that there are falsehoods involved. We might hold that the general claims of economics such as price equals marginal product are really generalizations with an implicit clause saying “assuming other things are equal.” Thus the laws used to explain are not false but qualified ceteris paribus. This view is sometimes supported by arguments that even in physics the fundamental laws are qualified ceteris paribus (see [Cartwright, 1984]) — the force on a body due to gravity is equal to mass times acceleration only assuming no other physical forces are present.

Several objections have been raised against this defense [Earman and Roberts, 1999; Earman et al., 2002]. There is the worry that treating economic claims as qualified ceteris paribus renders them nonfalsifiable or makes them superfluous. Either we can specify what the “other things being equal” are or we cannot. If we cannot, then social claims qualified ceteris paribus seem unfalsifiable, for every failed prediction has an out — other things weren’t equal. If in fact we can specify what those “other things” are and show that the model is accurate when they are present, then these conditions can just be added in and we do not need to think of social science claims as qualified ceteris paribus at all. Moreover, it is not clear that the basic laws of physics are qualified ceteris paribus. It is true that the fundamental laws describe different fundamental forces and that real explanations frequently have to combine those forces. However, in many cases it is possible to say how the forces combine.

Another objection, not commonly recognized, to the ceteris paribus defense is that all the attempts to spell out ceteris paribus laws implicitly presuppose the nomological-deductive account of explanation. It is assumed that to show that models explain is to show that they embody laws. However, as I argued above, that seems a misguided approach, for the connection between explanation and laws is neither obvious nor fundamental.

Perhaps a more defensible version of the other things being equal strategy is this. Traditionally philosophers have thought of theories as a set of sentences. However, there are various difficulties with this syntactic view of theories. In response to those difficulties some have proposed what is called the semantic view of theories. Putting complexities aside, the semantic view denies that theories are set of statements that are either true or false of the world. Theories instead are defining abstract entities-possible models. Thus the theory of evolution is defining an possible entity, namely, a Darwinian system. That system is one in which there is heritable variation and selection. On the semantic view of theories it is a separate and further empirical question whether there is anything in the world corresponding to the abstract entity described by the theory.

Viewing social science theories from the semantic view of theories certainly avoids the awkwardness of claiming that social science generalizations are true ceteris paribus. However, it may be that it does so simply by putting the problem elsewhere, for we still have the problem of which models actually describe the world and which do not-or put differently, how does a model of a possible reality explain the actual world if it makes assumptions not true of it?

These questions are pursued by a sizable literature in general philosophy of science on the role of models. That literature suggests a number of possible alleged ways that models might capture reality despite their unrealistic assumptions that have been proposed in the literature. Among them are that a model explains if:

1. it provides “insight”. This is a common informal rational given by social scientists in defense of particular models.

2. it unifies, i.e. shows how different phenomena might be captured by the same model [Morgan and Morrison, 1999].

3. it serves as an instrument — we can do things with it [Morgan and Morrison, 1999].

4. it is isomorphic to the phenomena of interest [Giere, 1988].

5. it fits the phenomena into a model [Cartwright, 1984].

No doubt there is something to all these claims. Yet none of them by itself seems sufficient to help us tell the good unrealistic models from the bad. Insight threatens to be nothing more than a warm, fuzzy intellectual feeling — we need some kind of explanation of what insight is, how we tell when it is legitimate, and so on. Models that apply across diverse phenomena generally gain some kind of support from doing so. However, it is also possible to tell the same false story over and over again about different phenomena. Many have accused advocates of rational choice models with highly unrealistic assumptions (perfect foresight, etc) of doing just that. Likewise, it is surely right that models serve multiple functions, among them allowing manipulation of components to determine consequences. Still, we can manipulate an abstract model that applies to nothing at all — when does manipulation show that we are capturing real processes rather than imaginary?

The idea that good models are those that stand in some kind of one to one relationship with things in the world is also insufficient, though it is more promising than the previous criteria. However, how do the idealizations of a model stand in a one to one relation to the world exactly? Do the agents with perfect foresight in the market economy model stand in such a relation to real world agents? We can posit a relation, but the question still seems to remain whether doing so explains anything. Moreover, when models are based on abstractions — the leaving out of factors — there is presumably nothing in the model that represents them. How do I know that is not a problem?

One reasonable route around the problems cited above is to focus on finding causes. If we have evidence that a model with unrealistic assumptions is picking out the causes of certain effects, then we can to that extent use it to explain despite the irrealism. If I can show my “insight” is that a particular causal process is operative, then I am doing more than reporting a warm feeling. If I can show that the same causal processes is behind different phenomena, then unification is grounded in reality. If I can provide evidence that I use my model as an instrument because it allows me to describe real causes, then I can have confidence in it. Finally, if I can show that the causes postulated in the model are operative in the world, I can begin to provide evidence that the model really does explain.

How is it possible to show that a model picks out real causes even though it is unrealistic? Social scientists adopt a number of strategies to do so. Sometimes it is possible to show that as an idealization is made more realistic, the model in questions improves in its predictive power. Another strategy is doing what is known as a sensitivity analysis. Various possible complicating factors can be modeled to see their influence on outcomes. If the predictions of a model hold up regardless of which complicating factors are added in, then we have some reason to think the model captures the causal processes despite its idealizations or abstractions. There are a number of other such methods potentially available to social scientists. After all, the natural sciences use idealizations and abstractions on a regular basis with success, so there must be ways of dealing with them.

5 Macro and Microexplanation

A key longstanding methodological debate within economics has been about the proper role of microexplanations and macroexplanations. The official ideology of main stream economics is methodological individualism which gives some kind of priority to individuals in explaining the economic. However, that priority can take different forms, and in what follows I discuss some of them and their plausibility.

The standard short form slogan of methodological individualism is that all economic explanations should be in terms of individuals. However, this can mean multiple things with rather different implications. Some of the possible claims are:

1. Any well confirmed economic theory can be reduced to an account solely in terms of individuals.

2. Facts about individuals determine the facts about economic aggregates.

3. Reference to individualist mechanisms is necessary for successful explanations of economic phenomena.

4. Seeking individualist explanations is the most fruitful research strategy in economics.

There are of course interconnections between these claims and they too admit of multiple interpretations. I deal with both as I discuss each thesis.

Individualism as a claim about theory reduction can be fairly precisely delineated, since there is a fairly substantial literature in the history and philosophy of science to rely on. Newtonian mechanics can be reduced to general relativity in the limit case of low velocities and thermodynamics reduced to statistical mechanics.3 To reduce one theory to another is to show that one theory can explain everything the other can and is in some sense more basic. Reduction is at issue only if two theories say apparently different things or describe the world in different categories. Thus if one theory is going to explain what another does, then there must be some way to capture the categories of the reduced theory in the reducing theories own terms. One standard way of doing so is by providing bridge laws of the form “Reducing theory term A is applicable if and only if reduced term B is applicable.” The connection need not be shown to be conceptual or true by the meanings of the words; lawlike equivalence suffices. Thus temperature is lawfully coextensive with “mean kinetic energy” and that works for reduction even if we wouldn’t equate them in ordinary language as synonyms. Furthermore, such bridge laws need not capture the reduced term exactly, for the reducing term may be shown to be vague in various ways in the process of reduction. What is needed is then is at least an analogue of the reduced term, and the further the analogue is away from the original term, the closer the reduction will be to a simple elimination and a denial that the reduced theory explains much of anything.

It is standard to argue that reduction is achieved if we can provide the bridge laws linking the two domains and then show that the generalizations of the reduced theory are captured as generalizations of the reducing theory as when we can derive the gas laws from statistical mechanics with the help of the bridge law relating temperature and mean kinectic energy. However, this is wrong. It is wrong because it assumes that the essence of explain is deriving generalizations, something that we saw earlier was problematic. Moreover, we can have bridge laws that beg the question for reduction — for example, emotions were sometimes translated by behaviorist reductions to emotion laden behavioral terms, e.g. anger behavior.

Given the above account of reduction, we can list two potential obstacles to reduction:

1. multiple realizations where the reduced theories’ basic categories are brought about in indefinitely many ways by the reducing theory. In this case there is a many-one relation between the basic terms and thus no coextension bridge law is to be had.

2. presupposing the reduced theory in the reducing explanations as happens in explaining emotions in behavioral terms such as “anger behavior.”

Whether these potential problems are real has to be shown empirically, case by case. There is evidence to think they are indeed sometimes real in economic explanation.

The multiple realizations problem is likely in the many cases where economics explains aggregate phenomena, though for several different reasons. One source of problems comes when we explain aggregate phenomena in terms of competitive selection between aggregates. Firms are a prime example. There is a long, largely informal tradition of arguing that the standard maximizing traits will be found in firms because those without them will not survive. There is a much more formal body of work applying evolutionary game theory to the strategies of firms. In both cases, the selection process does not “care,” as it were, about how firms bring about their strategies in terms of organizing individual behavior. All that counts is that the strategy is played. This means that if firms hit on different ways of realizing the same organizational strategies in the behavior of individuals, it will make no difference to processes at the aggregate level.

However, we have good economic reasons for thinking that there are many ways to produce standard firm characteristics such as hierarchical structures, long term employment relations, etc. A variety of different individual level models have been offered in the literature for these practices, e.g. incentives not to shirk, transaction costs, and many other mechanisms can logically do the trick (see [Kincaid. 1995]).

Another area where we might expect multiple realizations to be real phenomena is in macroeconomics. There are several reasons for this. (1) Scale relativity: real causal patterns may be identified at one scale of measurement and not available at another. This is a common theme in the literature on complexity and has been used as an argument against reductionist programs by philosopher’s of science [Ladyman and Ross, 2007] and specifically in the case of macroeconomics by Hoover [2001], though he does not use this terminology. Aggregate concepts like GDP lose any definite sense at some point if we look for finer and finer grained measures in terms of individual behavior. So multiple realizations are inevitable because the lower equivalent is indeterminate. (2) Even when we can make sense of translating aggregate macroeconomic concepts into individualist terms, it is quite likely that there are many different sets of individual behaviors that can bring about the aggregate phenomena like the rate of inflation because they describe aggregate averages where the averages do not determine the distribution from which they result.

A second likely obstacle to reduction comes from the fact that many so called individualist explanations are really individualist only in name. This occurs for two reasons. First, what is labelled an individual in economics is not always an individual human being. So firms are treated as individuals, for example. More drastically still, many economic models use “representative agents”-they treat aggregates of individuals as if there were individuals with well-defined utility functions, etc. There is an unrefuted literature showing that this methodology cannot be defended on the grounds that the behavior of individual human beings will aggregate in such a way that they will in total act like an individual with a well defined utility function. So representative agents do not fit well with methodological individualism.

There are also deep questions whether standard neoclassical economics is actually about individual human beings at all. Ross [2005] argues that neoclassical formalism is silent on what agents actually it covers — there is nothing in the formalism per se that have to make neoclassical theory about individual human beings. Moreover, the extensive and replicated results from experimental economics seems to show that individual human beings violate many of the assumptions of the neoclassical models of individual choice. That does not rule out a methodological individualism based on more realistic theories of individual behavior, but it is standard choice theory that is usually pointed to as an example of what a good individualist theory should look like. This point is telling also against versions individualism discussed later that require only individualist mechanisms.

Individualist theories in economics, even if they are plausible accounts of individual human behavior, can nonetheless fail to support the reductionist program. They can implicitly or explicitly presuppose accounts of nonindividual economic entities. Work in classical game theory is good illustration. Game theory accounts of particular phenomena begin with a set of strategies, payoffs, kinds of players, and shared knowledge. However, all these things arguably presuppose that institutions are already in place (Kincaid 2001). Common knowledge assumptions are a standard way to explain norms and conventions, so to assume them is to assume the conventions or norms are already in place. Differentiating players into types that are known assumes the social organization involved in establishing and reinforcing social statuses or roles. A constrained set of possible strategies from all the logically possible ones assumes the kind of shared understandings and social possibilities that come with a definite social organization as the do preset payoffs of actions. This does not mean there is necessarily anything wrong with these explanations, but it does mean they do not adhere to the strictures of methodological individualism.

Let’s turn next to some of the logically weaker claims associated with methodological individualism that were listed at the beginning of this section. If full individualist reductions are not likely, might it still not be the case that economic explanations must supply individual mechanisms — must describe how individuals acting on their preferences under constraints bring about the phenomena to be explained?

This certainly does not follow from any general scientific demand for mechanisms for two reasons. While physics during much of its development required mechanisms in the sense of a continuous causal process, that was called into question by the development of quantum mechanics with its action at a distance. Furthermore, mechanisms can be described to different degrees and at different levels. Cosmology provides causal mechanism but at a very aggregate level. Every day life is full of causal explanations without molecular details. Such explanations can be as well confirmed as any. So there is no all-purpose demand for mechanisms in explanation.

A more useful way of thinking about the need for mechanisms is to consider three questions: how good is our evidence at the aggregate level? What do our explanations at the aggregate level assume about processes at the levels below? How good is our knowledge at the level of entities composing the aggregate? It is clear that the answers to these questions is an empirical matter and nothing a priori ensures that in some circumstances we might know much at the aggregate level, do so without presupposing anything specific at the microlevel, and have no good causal knowledge at the lower level. It then becomes a case by case empirical issue whether mechanisms are required.

6 Functional Explanation and Evolutionary Economics

There is a long-standing tradition in the social sciences in general of explaining social practices by the functions they serve. These explanations also occur in economics, though economics is generally more explicit that they are connected to competition and selection mechanisms. I want to discuss some general issues about such explanations, though I will not take up the full the set of issues about evolutionary economics that lie in the background.

The most commonly cited problem with functional explanations is that seem committed to an unscientific teleology. The general consensus is that explaining social phenomena by the functions they serve is legitimate only if there is a causal process tying useful effects to the existence of the practice in question. It is often claimed that doing so requires biological analogies that are only metaphorical and have no realistic social counterpart.

Elster provides one early account of what this involves. A functional explanation of the form A exists in order to B for group C is valid only if:

3. B is an unintended consequence and unrecognized for the actors in C

4. B maintains A by a causal feedback loop running through C

There are several problems with this account, however. For one, it makes it essential that functional explanations are in part about individuals, but this imposes are strong methodological individualism that is implausible in economics as I have already argued. One important strand of functional argument in economics is that which sees the behavior of firms as determined by a competitive process such that we can be sure that firm strategies exist in order to maximize profits. Another important strand of argument [Friedman, 1953; Nelson and Winter, 1982] is that these competitive processes can operate and be described independently of the motives of individuals. Elster would rule this out by fiat.

A second problem is that a mere positive feed back loop between effects and what is being explained is a much too broad a notion of functional explanation.

Processes where A can cause B and that effect in turn can reinforce As persistence describe a very wide variety of causal processes indeed. Any system in an equilibrium situation where the mutual interaction between variables keep each in a set range will be a functional explanation.

So I would argue that a more helpful account of functional explanation is the following [Kincaid, 2007]:

2. A persists because it causes B

3. A is causally prior to B, i.e. B causes A’s persistence only when caused by A.

The first claim is straightforwardly causal. The second can be construed so as well. At t1, A causes B. That fact then causes A to exist at t2. In short, A’s causing B causes A’s continued existence.4

The third requirement serves to distinguish functional explanations from explanations via mutual causality. If A and B interact in a mutually positive reinforcing feedback look, then A causes B and continues to exist because it does so. Yet the same holds for B vis-à-vis A. Functional explanations do not generally have this symmetry. Thick animal coats exist in order to deal with cold temperatures, but when cold temperatures are present there is no guarantee that thick coats arise. And surely, even if they do, there is no reason that would they do not cause the cold to persist.

So functional explanations in economics can be perfectly legitimate if they satisfy these three explicit causal requirements. Could they do so without making false biological analogies? The most general description of a causal system describes a set of variables whose values evolve through state space. At this level of description we are told very little: current entities stand in some relation to past ones. Natural selection is inevitably an instance of this as a causal system satisfying the three conditions above. Functional explanations as causal are also an instance. Every causal system is analogous in being a dynamical system. The point here is that whether one set of causal relations is analogous or disanalogous to another depends on the level of description we are using.

So at the most abstract level it is a trivial truth that functional explanations are indeed analogous to Darwinian evolutionary systems in so far as they are causal systems. They are disanalogous in that social entities have no DNA that replicates. But then the HIV virus has no DNA either (it is an RNA virus). We find analogous processes in DNA and RNA organisms despite the differences because we abstract from the details to identify abstract causal patterns.

So do functional explanations commit us to some illegitimate analogy to natural selection? No, because natural selection explanations are just one realization of the above schema which is thus the more general pattern [Kincaid, 1986; Harms, 2004]. A’s causing B may result in A’s persistence by means that don’t involve genetic inheritance, literal copying of identifiable replicators distinct from their vehicles or interactors, etc. In fact not all biological processes of natural selection require this level of analogy — differential survival can be caused by other processes (see [Godfrey-Smith, 2000]).

In this regard, Pettit [1996] notes that explanations of this general form do not even require a past history of selective processes. He argues that to establish a functional explanation we need only prove “virtual selection.” Virtual selection refers to processes that would exist if some social practice with beneficial effects were to change. Suppose golfing may not be present now because of the positive benefits it had in the past, but if golfing were now challenged, then there would be pressures to maintain it. This virtual selection is just one way to make it true that A persists because it causes B, where B is a beneficial effect.

If differential selection processes can undergird functional explanations in economics, there still remain many unresolved issues about such explanations. Two I want to concentrate on here are the level at which selection acts and the relation of functional explanations to other kinds of explanations. Biologists and philosophers of biology have debated the prospects for group selection processes over and above selection on individuals. An emerging consensus on biological and social evolution [Sober and Wilson, 1998] sees natural selection as a multi-level process that can act at various levels. Group selection of a trait occurs when the trait is differently distributed in different groups in a population and those groups with a higher frequency of the trait are thereby more fit in that group size increases relative to other groups. In this situation the frequency of a trait can increase in the population as a whole, even though it may be less fit in each group. If the effects on group productivity are strong, the trait can evolve. Advocates of evolutionary game theory in economics have transported this consensus view into their analyses [Bowles, 2003].

However, there remains an important ambiguity in how group selection is understood that has consequences for evolutionary game theory in economics. Note two things about this notion of group selection. The fitness of the group is defined by ability to increase in size — to increase the number of individuals in the group. Thus the unit of measurement is individual organisms or economic actors specified by trait or strategy type. It is this choice of unit that makes an intergrated multilevel account possible: the effects of genic, individual, and group selection are compared in terms of differential survival of individual organisms of specified types.

However, there is another sense of group selection that sometimes is invoked without noting the difference. So group selection can occur when there are different kinds of groups that produce new groups that resemble them, when groups vary in their traits, and those traits have varying influences on the next generation. This is group selection where the units of measurement are groups, not individual organisms. If a trait leads to more groups of one kind, there can be group selection regardless of what happens to the number of individual organisms in them. Arguably this notion of group selection is what various biologists and social scientists have had in mind. It was explicitly contrasted with the current consensus notion in the mid 1980s [Kincaid, 1986; Damuth and Heissler, 1987].

The complications introduced by group selection in the second sense have not received sufficient attention. Group selection in the multilevel sense of Sober and Wilson studies a different dependent variable than that selectionist accounts based on the survival of groups. Thus, the claims of multilevel selection to integrate both group and individual processes. There are also complex issues surrounding the very idea of selection “acting at a level” that I cannot address here. But at the very least it is important to keep the two different senses of group selection — differential survival of individuals because of group membership and differential survival of types of groups — distinct.

The second complication mentioned above concerns how functional explanations in economics relate to other causal processes. While it is common to make claims such as “long term contracts exist in order to minimize transaction costs” as if the phenomena were fully explained, it is quite possible for functional causes to coexist with other nonfunctional causes. Game theory explanations are a nice case in point. When there are multiple equilibria, then when an equilibrium is reached, we can explain it as existing and persisting because it is optimal. However, this functional explanation has to be compatible with whatever explains why one equilibria exists rather than another. If we think of explanations as answering questions that can vary according to context, then game theory might answer the question “why is there some norm rather than none” while leaving the question “why this norm rather than that?” unanswered.

A final interesting question about functional explanations in economics as I have described them concerns the relation between models invoking differential survival and those involving learning. Vromen [1996] has argued that adaptive learning models are not consistent with evolutionary explanations. Selection processes require static individuals but adaptive learning prevents that. I think Vromen is right to the extent that the two factors have to be explicitly incorporated and that simply mentioning adaptive learning as a basis for evolutionary and hence functional accounts is insufficient. However, I think it is clear that learning can be combined with selection and in fact be described in selectionist terms. One key to seeing this is to recall that selection processes can be defined very abstractly and that learning is a kind of differential survival. Furthermore, there are existing models that show how both learning and differential survival of individuals can be combined [Boyd and Richerson, 2005].

7 The Nature of Economic Causes

An interesting set of issues arises in connection with the ontological nature of causation in the economic realm. Recall the growth theories discussed earlier. I pointed out that these are frequently taken to provide nomological deductive explanations. However, they are not uniformly taken this way. They are also taken to describe the causes of economic growth. They are typical of much economics: a set of equations with some kind of causal interpretation is laid out and then tested by statistical means — usually by some form of regression analysis.

This general project relies on specific presuppositions about how economic causes work, something we should expect given general framework advocated above where claims about explanatory virtues are substantive empirical and often domain specific claims. These presuppositions come in the way the causal relationships are described and in the kind of data that is thought relevant. Let’s take the simplest case illustrated by the current neoclassical growth theories. Growth is the dependent variable and is claimed to be causally influenced in either a negative or positive direct by a set of independent variables. A data set is obtained, sometimes cross sectional and sometimes panel data, with information about growth rates and their possible causal influences from many different countries. Regressions are then fitted to that data, with some possible independent variables being declared relevant and others irrelevant on the basis of significance tests.

As a vibrant literature on this paradigm in sociology and political science points out [Abbott, 2001], there are very strong causal assumptions lurking, ones that are often not true of the social world. The project represented by neoclassical growth theory makes these same kind of assumptions, namely:

1. Fixed entities with attributes. There is a universe of individuals and a fixed set of properties that are distributed among them. There is a fixed set of countries and a fixed batch of properties that are relevant to all

2. Constant causal relevance. There is one set of the causes of growth that are always part of the causal story.

3. Common time frame for causes and effects and for partial causes of the same effect. The measured fluctuations in the causal variables occur in the same time frame as each other and as the fluctuations in the effect variables. Changes in the determinants of growth occur over a one year period as do the changes in growth, precluding the duration of the causing event and the effect event from occurring at different time scales.

4. Uniform effects. The influence of a variable cannot vary according to context. There is one production function common to all countries. If the influence of a variable depends on the level of another variable, then the model is misspecified and a further variable representing the interaction effects of the two variables needs to be added. The resultant model then has every variable with a constant effect. In short, context can always be removed.

5. Independent effects. Each causal factor makes an independent contribution to the effect — their causal influence is separable.

6. Causal influence is found in variations of mean values.

7. Causation is not asymmetric. Increases in the value of a causal factor will increase the size of the effect and decreases will decrease the size of the effect.

The important point is not that these presuppositions cannot be true. They can be. But they are very strong assumptions when it comes to explaining complex economic and social phenomena. To return to our previous example, growth theory as pursued by development economics as opposed to neoclassical growth theory provides plenty of situations where these assumptions are highly implausible. Let me mention three.

Necessary causes are important in growth. Education, for example, seems not to suffice for growth (think of Cuba) but it may be a necessary requirement. Infrastructure of other sorts — e.g. roads — have a similar place. However the picture of causation in the equation and regressions approach has no place for necessary causes — all causes are individually sufficient to produce some effect. Causation is often conjunctural — it takes factors in combination to produce a given outcome. So the long standing idea of complementarities — which now has made it into rigorous models — describes exactly such a situation. Conjunctural causes do not fit easily with the regression and equations approach. Levels matter for how factors influence growth. There are probably “tipping points” in economic growth — situations where at a low level some factor has not effect but must reach some higher level to spur growth.

8 Conclusion

Naturalism in the philosophy of science suggests that philosophy of science has to be continuous with science itself and that it cannot produce useful a priori conceptual truths about explanation. Issues about the nature of explanation are scientific issues, albeit ones that certainly can gain from careful attention to clarifying the claims involved. Not surprisingly, the scientific issues surrounding explanation in economics vary according to the part of economics that is under scrutiny. Clarifying claims about economic explanation in the concrete can shed both light on the economics and on our philosophical understanding of explanation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Abbott A. Time Matters Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001.

2. Alchian A. Uncertainty, evolution and economic theory. Journal of Political Economy. 1950;58:211–221.

3. Barro R. Determinants of Economic Growth Cambridge: MIT Press; 2001.

4. Beller M. Quantum Dialogues Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999.

5. Berk R. Regression Analysis: A Constructive Critique Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004.

6. Bowles S. Microeconomics: Behavior, Institutions, and Evolution Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2003.

7. Boyd R, Richerson P. The Origin and Evolution of Cultures Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

8. Cartwright N. How the Laws of Physic Lie New York: Oxford University Press; 1984.

9. Cartwright N. The Dappled World New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

10. Earman J, Roberts J. Ceteris Paribus, There Is No Problem of Privisoes. Synthese. 1999;118:439–478.

11. Earman J, Roberts J, Smith S. Ceteris Paribus Lost. Erkenntnis. 2002;57:281–301.

12. Friedman M. The Methodology of Positive Economics. In: Essays in Positive Economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1953.

13. Garfinkle A. Forms Of Explanation: Rethinking Questions In Social Theory New Haven: Yale University Press; 1981.

14. Giere R. Explaining Science Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1988.

15. Godfrey-Smith P. The Replicator in Retrospect. Biology and Philosophy. 2000;15:403–423.

16. Harms W. Information and Meaning in Evolutionary Processes Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

17. Hausman D. Causal Asymmetries New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

18. Heisler J, Damuth H. A method for analyzing selection in hierarchically struct[ured populations. The American Naturalist. 1987;130(4):582–602.

19. Hoover K. Causality in Macroeconomics Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

20. Kaplan J. The Limits and Lies of Human Genetic Research London: Routledge; 2000.

21. Kincaid H. Explaining Growth. In: Kincaid H, Ross D, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008.

22. Kincaid H. Functional Explanation and Evolutionary Social Science. In: Risjord, Turner, eds. Handbook of the Philosophy of Social Sciences. 2006.

23. Kincaid H. Optimality Arguments and the Theory of the Firm. In: Little Daniel, ed. The Reliability of Economic Models: Essays in the Epistemology of Economics. Boston: Kluwer; 1995;211–236.

24. Kincaid H. Philosophical Foundations of the Social Sciences: Analyzing Controversies in Social Research Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

25. Kincaid H. Assessing Game-Theoretic Accounts in the Social Sciences. In: Proceedings of the Congress on Logic, Methodology and the Philosophy of Science. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2001.

26. Kitcher P. Explanatory Unification and the Causal Structure of the World. In: Salmon W, Kitcher P, eds. Scientific Explanation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1989.

27. Ladyman J, Ross D. Everything Must Go Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

28. Mäki U. Some non-reasons for non-realism about economics. In: Mäki U, ed. Fact and Fiction in Economics Realism, Models, and Social Construction. Cambridge University Press 2002;90–104.

29. Mankiew N. The Growth of Nations. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1995;25:275–310.

30. Morgan M, Morrison M. Models as Mediators Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

31. Nelson R, Winter S. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1982.

32. Northcott R. Pearson’s Wrong Turning: Against Statistical Measures of Causal Efficacy. Philosophy of Science. 2005;72:900–912.

33. Pettit P. Functional explanation and virtual selection. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 1996;44:291–302.

34. Romer P. Endogenous Technological Change. Journal of Political Economy 1990.

35. Romer P. The Origins of Endogenous Growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1994;8:3–22.

36. Ross D. Economic Theory and Cognitive Science: Microexplanation Cambridge: MIT Press; 2005.

37. Sklar L. Physics and Chance Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

38. Sober E, Wilson D. Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1998.

39. Solow R. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1956;70:65–94.

40. Sutton J. Technology and Market Structure: Theory and History Cambridge: MIT Press; 1998.

41. Vromen J. Economic Evolution London: Routledge; 1996.

42. Woodward J. Explanation, Invariance, and Intervention. Philosophy of Science. 1997;64:S26–S41.

43. Wright L. Functions. Philosophical Review. 1973;82:139–168.

1 For a much longer discussion of growth theories and issues in the philosophy of science, see [Kincaid, 2008].

2 The discussion that follows draws on Northcott [2005] discussion on causation, the extensive body of work pointing out the flaws in heritability measures in biology which rest on explained variance (see [Kaplan, 2000] and that in the social sciences debunking overinterpreting regression results [Berk, 2004]).

3 In actual practice the latter is not as straightforward as typically presented. See [Sklar, 1995].

4 Wright’s [1973] account is a partial inspiration here, but it has to be stripped of its conceptual analysis pretensions. And the requirement here is explaining persistence rather than existence.