Geographical Economics and its Neighbours — Forces Towards and Against Unification

1 Introduction

The neglect of spatial issues in economics has been “one of the great puzzles about the historical development of economics” [Blaug, 1996, p. 612]. Economic activity clearly does not take place in the proverbial head of a pin: space and distance do affect economic activity in a non-trivial way. Aimed at ending the long silence of the economics discipline on the spatial economy, a new approach developed at the beginning of the 1990s. Almost by accident, Paul Krugman, at that time already well known for his contribution to new trade theory, noticed that a small modification to his new trade models would allow the endogenous derivation of spatial agglomeration: the New Economic Geography was set off. Later, partly as a reaction to the complaints of “economic geographers proper” [Martin, 1999], the New Economic Geography became also known as geographical economics [GeoEcon, henceforth], a label that more clearly underscores its disciplinary origin. Today, GeoEcon is a well-established field of economics [Fujita et al., 1999; Fujita and Thisse, 2002; Brakman et al., 2001; Baldwin et al., 2003].1 GeoEcon appears to have successfully brought geography back into economics.

Why did GeoEcon succeed in bringing spatial issues to the attention of mainstream economics? A complete answer to this question possibly requires appeal to a wide range of institutional, social and historical factors. Allowing a certain degree of simplification, however, the GeoEcon adherence to the scientific and methodological standards that are most cherished by economists appears to explain a great deal of its success. According to its proponents, GeoEcon’s contribution, vis-à-vis extant theories dealing with the spatial distribution of economic activity, is twofold. First, GeoEcon shows that similar economic mechanisms are at work in bringing about a host of phenomena that were previously studied by separate disciplines. In doing so, it addresses Ohlin’s call [1933] for the unification of trade theory and location theory. Second, GeoEcon is the only field within economics that provides a micro-foundation in a general equilibrium framework for the spatial distribution of economic activity. Both contributions satisfy widely held scientific ideals of economists: the desire for unified theories and the search for micro-foundations.

On the face of it one would expect economists and social scientists concerned with spatial/geographical issues to have welcomed the GeoEcon appearance. Reactions have been rather mixed instead. Urban and regional economists and regional scientists claim that the theoretical ideas on which GeoEcon models rest are not new; they have just been dressed up differently. Economic geographers charge GeoEcon of several flaws: it is just another instance of imperialism on the part of economics; it subscribes to positivist ideals, which geographers rejected long ago; its models are overly unrealistic, and therefore incapable of explaining relevant aspects of real-world spatial phenomena.

In this Chapter, I examine topics arising in the context of GeoEcon and its neighbors that are of interest from a philosophy of economics perspective, namely explanatory unification; theoretical unification and inter-field integration; economics imperialism; and theoretical models, their unrealistic assumptions and their explanatory power. Two main themes run through the Chapter and knit the various topics together. The first theme concerns the web of inter- and intra- disciplinary relations in the domain at the intersection of economics and geography that have been affected by GeoEcon. The second theme concerns the role played by the pursuit of unification and the search for micro-foundations both as drivers of the GeoEcon theoretical development and as vehicles through which inter- and intra-disciplinary relations have been affected. The investigation of these themes reveals the co-existence of two sets of forces, forces towards and against unification, none of which succeeds to fully prevail over the other.

In dealing with these issues I follow recent trends in the philosophy of science and economics that appreciate the importance of looking at actual scientific practice as a means to supply a salient philosophy of economics. Although the value of general philosophical views is undeniable, the practical import of philosophy of economics is at its best when it delves into particular episodes and their specific contextual problems. In this Chapter, I show how philosophical ideas could help resolve the concrete problems faced by economists and their neighboring social scientists.

2 Geographical Economics and its Neighbours

GeoEcon seeks to explain the phenomena of spatial agglomeration and spatial dispersion as they occur at different spatial scales. The concept of agglomeration refers to seemingly very distinct empirical phenomena: the existence of the core-periphery structure corresponding to the North-South dualism; regional disparities within countries; the existence of cities and systems of cities, which are sometimes specialized in a small number of industries; industry clusters such as Silicon Valley; and finally the presence of commercial districts within cities such as Soho in London. Although each type of agglomeration could be the result of different types of agglomeration economies, geographical economists hypothesize that these apparently distinct phenomena are at least partly the result of similar mechanisms, viz. “economic mechanisms yielding agglomeration by relying on the trade-off between various forms of increasing returns and different types of mobility costs” [Fujita and Thisse, 2002, p. 1].

GeoEcon’s approach to spatial issues rests on two building blocks: the presence of increasing returns at the firm level and transportation/trade costs. Increasing returns at the firm level requires dropping the assumption of perfect competition and replacing it with that of imperfect competition, which in GeoEcon is modeled according to the Dixit-Stiglitz [1977] monopolistic competition framework. At the aggregate level, increasing returns and transportation costs give rise to pecuniary externalities, or market size effects. Pecuniary externalities are transmitted through the market via price effects and, simply put, their presence implies that the more firms and workers there are in a locality, the more the locality becomes attractive as a location for further firms and workers. This creates a cumulative process whose end result might be that all economic activity turns out to be concentrated in one location. While pecuniary externalities are forces that push towards the concentration of economic activity (agglomerating or centripetal forces), the presence of immobile factors, of congestion and the like, push towards dispersion (dispersing or centrifugal forces). The models are characterized by the presence of multiple equilibria: whether or not, and where, agglomeration arises depends on the relative strength of those forces and on initial conditions, that is, on previous locational decisions. The cumulative nature of the process of agglomeration is such that a small advantage of one location due to locational chance events in the past can have snowball effects which turn that location into the centre of economic activity, even though this outcome might not be the optimal one.

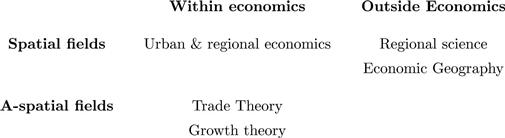

The domain of phenomena GeoEcon claims as its own was not terra incognita. There are a number of fields both within economics and without, whose domains overlap with that of GeoEcon: urban and regional economics, trade theory and growth theory within economics, and regional science and economic geography outside economics (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 GeoEcon’s neighbouring fields

Trade and growth theory are important and well-known bodies of work in economics. I will have more to say about them and their relation to GeoEcon in Section 4. For now it suffices to note that GeoEcon is perceived to have succeeded where others have failed: GeoEcon introduced spatial considerations in these traditionally a-spatial fields. Urban and regional economics deal instead with spatial and geographical questions (at the level of cities and regions respectively) but traditionally they have been somewhat marginal to the mainstream of economics.2 Although a number of urban and regional economists have generally downplayed the importance of the GeoEcon’s novel contributions, the general attitude has been one of acceptance; some of the recent contributions to the GeoEcon literature come from urban and regional economists. What is known as location theory constitutes the main overlap between urban and regional economics on the one hand and GeoEcon on the other hand. Location theory is a strand of thought whose origin traces back to the works of von Thünen, Christaller, Weber and Lösch, and refers to the modeling of the determinants and consequences of the locational decisions of economic agents. Location theory, trade theory and growth theory are the theories that GeoEcon purports to unify (Section 4 below discusses this aspect).

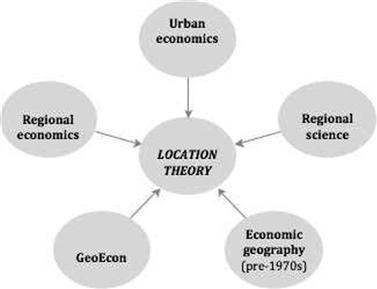

Outside economics, regional science and economic geography lay claim on substantial parts of the domain of GeoEcon. At the beginning of the 1950s Walter Isard established regional science as a field of inquiry that studies, with a scientific approach, social and economic phenomena with regional or spatial dimensions [Isard, 1975]. Influenced by the philosophy of science dominant at that time, the scientific approach was equated with the search for laws of universal applicability and with a strong emphasis on quantitative approaches. Regional science was thought of as an interdisciplinary field, bringing together economists, geographers, regional planners, engineers etc, and its ultimate aim was to provide a unified theory of spatial phenomena. Although regional science never reached the status of an institutionalized discipline, and failed in its unifying ambitions, the field is still alive today. Location theory is one of the principal themes that fall within the purview of regional science (see for example [Isserman, 2001]), and thus it is the area where urban and regional economics, regional science, and GeoEcon mostly overlap (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 The area of overlap between spatial fields.Location theory, the modeling of the determinants and consequences of the locational decisions of economic agents, constitutes the theoretical common ground between regional and urban economics, GeoEcon, regional science, and economic geography mostly before its critical turn in the 1970s.

Finally, economic geography is a relatively recent subfield of human geography. In the 1950s many regional scientists came from human geography, which at that time had left behind its characteristic ideographic approach to embrace the scientific ideals on which regional science was founded. In the span of twenty years, however, there was a fracture between the two fields that still lasts to these days. Geography went through its ‘critical’ turn, mainly inspired by Marxist ideas, and rejected altogether the philosophical and methodological commitments of regional science. The hostility towards abstract mathematical modeling based on maximization and equilibrium still characterizes contemporary economic geography. Economic geographer Allen Scott [2004, p. 483] lists, among others, an empirical turn, an interpretative turn, a normative turn, a cultural turn, a policy turn, and a relational turn that the field of economic geography undertook in recent years. Today the field is very rich both in its scope and methods. It is nevertheless common to characterize economic geography in terms of a special emphasis on the complexity of empirical reality, on place rather space, on concepts like contingency and specificity, and at the level of method, in terms of an extensive use of case studies and a discursive style of theorizing.3 It is therefore not surprising that the harsher criticisms of GeoEcon came from economic geography ([Martin, 1999] provides a wide ranging and influential critique of GeoEcon.) Some of these criticisms will be taken up in the following sections. But first let us examine GeoEcon and its unificationist features.

3 Explanatory Unification4

Explanatory unification broadly corresponds to the idea of ‘explaining much by little’, which is then cashed out differently in different proposals. The philosophical literature has almost exclusively focused on unification in the natural sciences, mainly physics and biology (exceptions are [Kincaid, 1997; Mäki, 1990; 2001]). And yet, unification is a widely held ideal shaping theoretical development in economics too. GeoEcon embraces this ideal: the unification of phenomena and theories is taken to be one of its principal contributions. Since unification in science is not a uniform phenomenon, much is to be learned about it from the way it takes place and drives theoretical development in actual practice. In what follows, guided by extant philosophical views on unification I offer a characterization of what unification amounts to in the case of GeoEcon.

I begin by distinguishing between explanatory unification and theoretical unification. Explanatory unification occurs at the level of phenomena, and it is a matter of explaining with the same, or fewer, explanantia several classes of explanandum phenomena. Theoretical unification instead occurs at the level of theories: it is a matter of unifying previously separate theories by means of a theory that possesses all (or most) of their explanatory content. In standard models of unification there is no room for such a distinction. What counts as a class of phenomena is defined by a theory, so that a theory that successfully unifies two classes of phenomena (the unifying theory) also unifies the respective theories (the unified theories). For instance, Maxwell’s theory unified electromagnetism and optics by showing that electromagnetic waves and light waves were one and the same thing; similarly, Newton’s theory unified Galileo’s laws of terrestrial mechanics and Kepler’s laws for celestial bodies by showing that the motions of celestial and terrestrial bodies could be explained by the law of universal gravitation. If the unifying theory is believed to be true (or more approximately true), then it just replaces the unified ones. The paradigmatic cases of unification in the history of science have often accomplished unification at both levels. The distinction between explanatory unification and theoretical unification nonetheless proves useful when examining actual social scientific practice where more mundane unifications take place.

The possibility of decoupling unification of phenomena and of theories arises from considerations of the following sort. Scientific theories differ on the basis of what they theoretically isolate as doing the explaining and as in need of explanation, and involve various degrees of abstraction and idealization [Mäki, 1992]. This also holds for theories that unify. Their isolations and idealizations however are likely to be different from those involved in the unified ones. Each theory, both the unifying and the unified ones, may then prove useful for different explanatory, predictive or heuristic purposes. Since social scientific theories often account for more than one aspect of a given phenomenon, a unifying theory might account for only a subset of the phenomena that the unified ones taken together explain. It can be argued that this only applies to non-genuine unifications, or at least to unifications that have not yet reached their full potential. In principle, the unifying theory, if it is truly unificatory, could be refined and extended so as to account for all the phenomena the previously separate theories accounted for. For my purposes, however, the ‘in principle’ issue can be left aside, so as to focus on the ‘in practice’ achievement of GeoEcon at the level of phenomena (this section) and at the level of theories and fields (next section).

The standard exposition of explanatory unification is Philip Kitcher’s [1981; 1989]. According to Kitcher [1989, p. 432], “science advances our understanding of nature by showing us how to derive descriptions of many phenomena, using the same patterns of derivation again and again, and, in demonstrating this, it teaches us how to reduce the number of types of facts we have to accept as ultimate (or brute).” In his view, to explain is to unify, and unification (and explanation) is a matter of inference and derivation. Unification proceeds via reducing the number of argument patterns while maximizing the number of explanandum sentences that can be derived. Kitcher’s account of unification seems particularly well suited to characterize theoretical development in economics (see [Mäki, 2001; Lehtinen and Kuorikoski, 2007b]). Economists do not use the vocabulary of ‘argument pattern’, or ‘pattern of derivation’; in their stead they talk about ‘models’, ‘derivations’, ‘theorems’ and ‘conclusions’. What we see in economics is that specific models are construed using a general type of model as template, and then derivations are performed within the model in terms of its inferential resources. This is in line with Kitcher’s own view that a general argument pattern can be embodied in a “general model type”. Unification in economics can then be seen to proceed via the application of a small number of similar model types to an ever-increasing number of economic and non-economic phenomena.

The way in which the GeoEcon unification has proceeded can also be largely captured by Kitcher’s account of unification. In Mäki and Marchionni [2009], we identify two model types that have so far effected the unification of different classes of phenomena and we supply a rough schematization of them as general argument patterns. These are the core-periphery model (set out in [Krugman, 1991]; henceforth CP model) and the vertical linkages model (set out in [Krugman and Venables, 1996]; henceforth VL model). Both model types rest on the Dixit-Stiglitz monopolistic competition framework with transportation costs, and derive the agglomeration of economic activity between two a priori identical locations. The difference between the two types lies in the foundation they postulate for the agglomeration mechanism. In the CP model, the size of the market in each location is determined by the migration decisions of workers: a larger market is a more attractive location for firms and through a reduction in the price of the goods also for workers. In the VL model, workers are immobile, and market size is made endogenous through the presence of input-output linkages between firms: the more firms in a location, the larger the market for upstream firms and the lower the costs for downstream firms. These model types are then filled in with specific variables to explain diverse classes of agglomeration phenomena. For instance, the general model type includes the abstract term ‘location.’ In each instantiation of the general argument pattern, ‘location’ is to be replaced with ‘zones within a metropolitan area’, ‘regions in a country’, or ‘regions involving more than one country.’5 (See [Mäki and Marchionni, 2009] for a full characterization of the argument patterns.)

In spite of the fact that Kitcher’s provides a good fitting model for the GeoEcon unification, it is still possible to keep, contra Kitcher, unification separate from both derivation and explanation. That is, we can ask the following questions: (1) Is GeoEcon unification achieved merely by way of deriving large numbers of explananda from a small set of patterns of derivation, or is it also a matter of revealing a shared ontology? (2) Is it the unifying component of the theory that yields explanation and understanding of the phenomena, or is it some other property of it? Geographical economists’ view and practice will supply the answers to these questions.

3.1 A shared ontology?

To address the first question I introduce two distinctions, which will help to characterize the kind of unification GeoEcon pursues and what it entails regarding unity among the phenomena. The first is Uskali Mäki’s distinction between explanatory unification of the derivational kind and explanatory unification of the ontological kind [1990; 2001], and the second is Margaret Morrison’s distinction between synthetic and reductive unification.

Derivational unification is a matter of deriving large classes of explanandum sentences from a parsimonious set of premises, theoretical structures or inferential patterns. Ontological unification instead is a matter of redescribing a large number of apparently independent phenomena as forms or manifestations of a common system of entities, capacities, or causes, thus revealing an underlying ontic unity between apparently diverse phenomena. Kitcher’s account is a variant of derivational unification, for it is an explicit attempt to cash out a notion of unification detached from the metaphysics of causation. Mäki [2001] however points out that although in some cases all that unification amounts to is derivation, in many cases derivational and ontological unification can go together. A theory might be conceived as unifying in virtue of unraveling the real unity among the phenomena, which is achieved by way of applying the same pattern of derivation to the explanation of diverse phenomena. In particular, Mäki [2001] provides some evidence that in economics unification often manifests itself as derivational unification with ontological grounding. The idea of a derivational unification with ontological grounding comes close to Salmon’s suggestion [1984] that the causal-mechanical and the unification views of explanation can be reconciled if scientific unity is seen as a product of delineating “pervasive causal mechanisms.”6Skipper [1999]expands on Salmon’s suggestion and proposes that on a causal-mechanical view of explanation, explanations that unify empirical phenomena proceed via the application of schematized causal mechanisms, what he calls “mechanism schema”.

The analysis of GeoEcon shows that the kind of unity pursued has to do with different phenomena being governed by similar kinds of economic mechanisms [Marchionni, 2004; Mäki and Marchionni, 2009]. If this interpretation is correct, then it makes sense to see GeoEcon unification as the successive application of a mechanism schema to different kinds of agglomeration phenomena. In other words, the CP and the VL model types are not merely two similar patterns of derivation. What the CP and the VL model types lay down and successive applications retain are schematized causal mechanisms, which are fleshed out according to the specifics of each explanandum phenomenon.

The second distinction concerns more specifically the kind of unity that a given unification entails at the level of the phenomena. Reductive unity is established when two phenomena are identified as being of the same kind (e.g. electromag-netic and optical processes; [Morrison, 2000, p. 5]). Synthetic unification instead involves the integration of two separate processes or phenomena under one theory (e.g. the unification of electromagnetism and weak force; Ibid: 5). Both reductive and synthetic unifications might be merely a logical or formal achievement; in Morrison’s view, the mere product of mathematical formalism. When the unifications involve more than that, however, the kind of implications regarding unity of the phenomena are different. Whereas reductive unification implies a reduction of one type of entities or processes to entities or processes of another type, synthetic unification can reveal the phenomena to be interconnected (Ibid: 177).7 Put it otherwise, there are two kinds of unity between the phenomena, “unity as single-ness” and “unity as interconnectedness” [Hacking, 1996]. Provided that they are more than just formal achievements, reductive unifications entail singleness at the level of phenomena whereas synthetic unifications entail interconnectedness.

The GeoEcon unification is not a matter of reducing one type of phenomena to another for say cities are not shown to be one and the same as industry clus-ters. What binds the phenomena together and permits their treatment under a unified framework is the presence of a set of common causal mechanisms, and the kind of unity at the level of the phenomena that GeoEcon entails is therefore one of interconnectedness. The unification of phenomena is not just a derivational achievement: GeoEcon applies the same mechanism schemata over and over again to explain diverse agglomeration phenomena, and by so doing it hopes to capture the ontic interconnectedness that binds these phenomena together.

3.2 What yields explanation?

The second question I posed above concerns whether what makes GeoEcon ex-planatory is its unifying power, or some other component or feature of the theory. Answering this question is not straightforward. Scientists might not be aware that their causal and explanatory judgments are derivative from judgments about unifying power. This has roughly been Kitcher’s reply to the criticism that in actual scientific practice causal talk is pervasive and often independent of unification. If Kitcher were right, actual scientific practice would be a poor arbiter to adjudicate between the primacy of unification vis-à-vis causation and vice versa. In conformity to the stand I take throughout this Chapter, however, I take seriously actual scientific practice. In this context, this means examining what geographical economists claim about explanation and identify what feature of the theory they regard as doing the explanatory work.

In economics, the widespread view is that a phenomenon is not genuinely explained if it cannot be derived from well-defined microeconomic parameters. This is roughly what is generally referred to as the thesis of methodological individualism. At the level of practice, this translates into the search for micro-foundations for theories about aggregates. GeoEcon fully embraces the economists’ view of what constitutes genuine explanation. To see this, it is instructive to look at geographical economists’ discussions of some of their predecessors.

A well-known theory whose origin traces back to Christaller and Lösch explains the existence of hierarchical systems of cities in terms of their efficiency in the provision of goods and services. Different locations enjoy different degrees of centrality, and places with higher locational centrality will not only offer the goods that less central places offer, but also those that the latter do not provide. The classical exposition of the theory is graphical and depicts cities as hexagons of different sizes. According to GeoEcon, central place theory is a “descriptive story, or an exercise in geometry” and not “a causal model” [Brakman et al., 2001, [p . 32]; see also [Fujita et al., 1999, p. 27]. The problem, so the argument goes, is that the equilibrium outcome, the hierarchy of cities, is not derived from the underlying behavior of consumers and firms. Recent regional science models seek to give central place theory a theoretical economic foundation, but still fail to deal with individual firms or consumers, so that the “central outcome is merely rationalized and not explained from the underlying behavior of consumers and producers, nor from their decisions and (market) interactions” [Brakman et al., 2001, p. 32, my emphasis]. GeoEcon at last provides an explanation for hierarchical systems of cities by deriving them from microeconomic considerations. In a similar vein, theories that rely on technological externalities and knowledge spillovers, which are common in urban economics and economic geography, are criticized for failing to genuinely explain agglomeration. The problem with technological externalities is again that their emergence cannot be derived from the behavior of economic agents; they are a black box (see [Fujita et al., 1999, p.4]. The following quote exposes this idea quite nicely:

The main thrust of the new geography literature has been to get inside that particular black box and derive the self-reinforcing character of spatial concentration form more fundamental considerations. The point is not just that positing agglomeration economies seems a bit like assuming one’s conclusion; as a sarcastic physicist remarked after hearing one presentation on increasing returns, “So you are telling us that agglomerations form because of agglomeration economies.” The larger point is that by modeling the sources of increasing returns to spatial concentration, we can learn something about how and when these returns may change, and then explore how the economy’s behavior change with them. [Fujita et al., 1999, p. 4]

If, as it seems, genuine explanation in GeoEcon has to do with the presence of micro-foundations, then having brought diverse phenomena under the same unified framework is not what makes the theory genuinely explanatory. And this is so, even though it is the search of micro-foundations that has helped to reveal that different classes of phenomena are governed by the same basic principles. For GeoEcon, unification is magnificent but it is not explanation (to paraphrase the title of Halonen and Hintikka’s article [1999]).

In addition, Morrison [2000] notices that in many cases of unification, not only unification is different from explanation, but also explanatory power and unifying power trade off against each other:

The more general the hypothesis one begins with, the more instances or particulars it can, in principle, account for, thereby “unifying” the phenomena under one single law or concept. However, the more general the concept or law, the fewer the details one can infer about the phenomena. Hence, the less likely it will be able to explain why particular phenomena behave as they do. If even part of the practice of giving explanation involves describing how and why particular processes occur — something that frequently requires that we know specific details about the phenomena in question—then the case for separating unification and explanation becomes not just desirable but imperative. [Morrison, 2000, p. 20]

In her view, unification typically involves less explanatory power because it occurs via a process of abstraction. More abstract and general laws may unify, but they have less explanatory power because they neglect details specific to the phenomena they are applied to. In order to explain diverse phenomena, the GeoEcon mechanism needs to be stripped down to its bare essentials. Geographical economists seem to be aware of this:

By using highly stylized models, which no doubt neglect a lot of specifics about urban/regional/international phenomena, geographical economics is able to show that the same mechanisms are at work at different levels of spatial aggregation … In order to lay the foundations for a unified approach, there is a price to be paid in terms of a neglect of institutional and geographical details… [Brakman et al., 2001, p. 323]

The above quote suggests that the GeoEcon unification could not be achieved without neglecting institutional and geographical details of different classes of agglomeration phenomena. When the theory is used to explain and understand particular aspects of specific phenomena, it is indeed not the unifying mechanism alone that bears the explanatory burden, but the specific ‘details’ too.8 Even so, the claim that there is a trade off between unifying power and explanatory power needs to be qualified. First, more details about the causal history of a phenomenon do not necessarily mean a better explanation. Morrison avoids committing herself to a particular view on explanation, but doing so deprives her argument of the capacity to discriminate those causal details that are explanatory from those that are not. (Mäki and Marchionni, [2009] discuss this in more detail.) Second, even if one holds that explanation is not tantamount to unification, one can still maintain that the unifying power of a theory constitutes one dimension on which its explanatory power can be assessed. I will have more to say about this in Section 6.3. Now, I turn to the discussion of the kind of unification that GeoEcon achieves at the level of theories and fields within economics.

4 Intra-Disciplinary Unification of Location, Trade and Growth

GeoEcon has been celebrated because it promises to unify the phenomena of location, trade and growth, previously studied by separate theories, thereby paving the way for the unification of location, trade and growth theories. The development of GeoEcon is closely tied to that of contemporary theories of trade and growth in the context of the “increasing returns revolution” or “second monopolistic revolution” in economics [Brakman and Heijdra, 2004]. GeoEcon is said to be the “fourth wave of the increasing returns revolution in economics” [Fujita et al., 1999, p. 3]. The revolution consists in shifting away from the constant returns to scaleperfect competition paradigm that dominated the discipline until the 1970s and 1980s to increasingly adopt the increasing returns-imperfect competition framework. Appreciating the way in which the increasing revolution has unfolded and led to GeoEcon is important in order to identify the main characteristics of the GeoEcon theoretical unification.

In what follows I briefly introduce the increasing returns revolution in economics, and the role played in it by a particular mathematical model, namely the Dixit-Stiglitz model of monopolistic competition (D-S model henceforth). The D-S model is not only what made the increasing returns revolution successful, but also what made GeoEcon and its unificatory ambitions possible. Next, I examine the kind of unification GeoEcon achieves at the level of theories and fields of research in economics. What the discussion shows is that theoretical unification is a much more complex and heterogeneous phenomenon than it is often assumed, and that models of integration between fields might be better suited than models of theoretical unification in characterizing the relation between GeoEcon and its neighbors within economics. This also constitutes the first opportunity to observe a tension between forces towards and against unification.

4.1 The fourth wave of the increasing returns revolution in economics

The first monopolistic competition revolution was triggered by the works of Chamberlin [1933] and Robinson [1933], but its impact on mainstream economics has been rather small. Johnson [1967] writes that

… what is required at this stage [viz. after Chamberlin and Robinson’s work on monopolistic competition] is to convert the theory from an analysis of the static equilibrium conditions of a monopolistically competitive industry…into an operationally relevant analytical tool capable of facilitating the quantification of those aspects of real-life competition so elegantly comprehended and analysed by Chamberlin but excluded by assumption from the mainstream of contemporary trade theory. [Johnson, 1967, p. 218]

For many economists the D-S model provides precisely that “operationally relevant analytical tool.” Its workability and analytical flexibility allows its application to a number of different areas of inquiry. Although the D-S model was originally conceived as a contribution to the literature on product differentiation, it was later applied to phenomena of international trade, growth, development and geography, all of which are taken to be the result of the presence of increasing returns. These new applications resulted in the development of “new trade theory” [Krugman, 1979; Dixit and Norman, 1980], “new growth theory” [Romer, 1987; Lucas, 1988; Grossman and Helpman, 1991] and GeoEcon. The impact of the “second monopolistic competition revolution” has therefore been much greater than that of its predecessor.

The application of the D-S model to phenomena of growth and trade largely follows a similar path. In both cases, the neoclassical variant was incapable of addressing some stylized facts and the presence of increasing returns was regarded as a possible explanation. Krugman describes the situation of trade theory around the 1970s as “a collection of highly disparate and messy approaches, standing both in contrast and in opposition to the impressive unity and clarity of the constantreturns, perfect competition trade theory” [Krugman, 1995, p. 1244]. It was thanks to the introduction of the D-S model that theories of growth and trade phenomena based on increasing returns became serious alternatives to the neoclassical ones. The result has been the development of new growth and new trade theory, which were treated as complementary to their neoclassical predecessors and in fact were later integrated with the latter.

The new trade theory enjoys a special role in the path towards unification of GeoEcon. In a sense, GeoEcon has developed out of a sequence of progressive extensions of new trade theory models. Witness the role of Paul Krugman as founding father of both new trade theory and GeoEcon. As observed by a commentator, “in stressing the relevance to regional issues of models derived from trade theory, Krugman has not so much created a new-subfield as extended the applicability of an old one” [Neary, 2001, p. 28]. Krugman [1979] shares with GeoEcon the presence of increasing returns and the D-S monopolistic competition framework, but it does not include transportation costs, an essential ingredient of the GeoEcon models. Krugman [1980], still a new trade theory model, includes transportation costs and differences in market size: together these assumptions imply that a country will produce those varieties for which the home demand is higher (market-size effect). In both Krugman [1979] and Krugman [1980] the distribution of economic activity is assumed to be even and fixed (agglomeration therefore cannot emerge). In a later work, Krugman and Venables [1990], uneven distribution of economic activity is introduced and thereby agglomeration can be shown to emerge. Yet, firms and factors of production are assumed to be immobile across countries, and differences in market size are given, not determined by the locational choices of the agents. It is the inclusion of factor mobility, which in turn endogenously determines market size, which generates the first GeoEcon model, namely Krugman [1991].

GeoEcon appears to provide a unified framework for the study of trade and location phenomena. Recent modeling efforts have also been made to integrate growth into the spatial models of GeoEcon. That geography is relevant for economic growth was clear before GeoEcon, and new growth models do allow for agglomeration of economic activity. Yet, differently from GeoEcon, “the role of location does not follow from the model itself and …it is stipulated either theoretically or empirically that a country’s rate of technological progress depends on the location of that country” [Brakman et al., 2001, p. 52]. Instead, GeoEcon models of growth aim to make the role of geography endogenous.9 Not only is GeoEcon one of the fields partaking in the increasing returns revolution, but it can also be seen as its culmination, as it holds out the promise to unify the most prominent theories engendered by the revolution.

4.2 Theoretical unification and inter-field integration

In 1933, Bertil Ohlin, a well-known international trade theorist, claimed that the separation between international trade theory and location theory was artificial: “International trade theory cannot be understood except in relation to and as part of the general location theory, to which the lack of mobility of goods and factors has equal relevance” (p. 142). Ohlin’s idea was that by allowing varying degrees of factor mobility and transportation costs, the difference between international trade, trade between regions within a country, or trade at the local level would be revealed to be just a matter of degree [Meardon, 2002, p. 221]. This unified theory of trade at different levels of geographical aggregation would naturally be a part of a general theory of the location of economic activity. Ohlin however was unable to accomplish the desired unification. As reported by Meardon [2002], the reason lied in the general equilibrium framework Ohlin was committed to. Within that framework, lacking any form of increasing returns, the introduction of factor mobility would lead to the equalization of the prices of factors, which was inconsistent with the empirical fact of persistent factor prices inequality. In 1979, Ohlin wrote:

… no one has yet made a serious attempt to build a general location theory and introduce national borders and their effects as modifications in order to illuminate international economic relations and their development by a method other than conventional trade theory. (Ohlin [1979, p. 6], quoted in [Meardon, 2002, p. 223]).

Only twelve years later, Paul Krugman [1991] published the seminal GeoEcon model. Thanks to the advancement in modeling techniques, Ohlin’s dream of a general theory of the location of economic activity within which trade and growth phenomena find their proper place might be on the way to its realization.

On the standard view of theoretical unification, GeoEcon, the unifying theory, would eventually replace international and location theory, and possibly also growth theory. The reason is clear enough. If GeoEcon had all the explanatory content of the separate theories, then the disunified theories would just be redundant. They could be retained for heuristic purposes, but from the point of view of explanation, they would be superfluous. Unifications in actual scientific practice however do not always satisfy this model. If the GeoEcon explanatory content only overlaps with and does not fully cover that of the disunified theories, then dispensing with the latter amounts to leave unexplained some of the stylized facts that were previously accounted for. In such situations, what we are left with is a plurality of partially overlapping theories. To generalize, we can think of theoretical unification as occurring in degrees, and distinguish complete from partial unifications. When the unifying theory does not explain some of the phenomena explained by the disunified theories, then we have a partial unification. When the unifying theory can account for all the phenomena that the disunified theories could separately account for, then the unification is complete (the unifying theory could also explain facts that none of the disunified theories explains).

At least thus far, the unification in GeoEcon is at best partial: There are a number of stylized facts about location, trade and growth that GeoEcon alone cannot account for. One of the reasons is that the distinct identity of GeoEcon lies in its focus on a certain kind of economic mechanisms (pecuniary externalities), which is believed to operate in bringing about diverse classes of phenomena. But there are other mechanisms and forces specific to each class that are not part of the GeoEcon theory. The relative importance of the alternative mechanisms and forces will vary so that whereas for certain stylized facts the GeoEcon mechanism will be more important than the specific ones, in other cases the reverse will be true. Economists in fact perceive growth theory (in both its neoclassical and new variant), trade theory (again in both variants), location theory and GeoEcon as complementary. This appears to be a relatively common feature: newer theories do not always replace old ones but they often live side by side and are deployed for different explanatory and predictive purposes. In our case, the different theories postulate different kinds of economic mechanisms as being responsible for their respective phenomena. Dispensing with one theory would amount to dispensing with one kind of mechanism and one possible explanation. Depending on the phenomenon we are interested in, a different mechanism or a different combination of mechanisms acting together will be relevant. This is where the complementarity between the different theories emerges. In principle, it could be possible that further developments in GeoEcon and neighboring fields will provide a general theory that tells us when, how and which combinations of mechanisms operate in bringing about the phenomena. But as things now stand we have no reason to believe so. What we now have is a plurality of overlapping, interlocking theories in different subfields, which GeoEcon has contributed to render more coherent and integrated.

So far I have focused on relations between theories. Now I take fields as the unit of analysis. It has been noted that standard models of inter-theoretic relations, including models of theoretical unification, do a poor job in depicting actual scientific practice and the tendencies towards unity therein. In their place, models of inter- or cross-field integration have been proposed as more appropriate. Integration between fields can occur via a number of routes, of which the unification of theories is just one. Darden and Maull [1977, p. 4] characterize a field as follows:

A central problem, a domain consisting of items taken to be facts related to that problem, general explanatory facts and goals providing expectations as to how the problem is to be solved, techniques and methods, and sometimes, but not always, concepts, laws and theories which are related to the problem and which attempt to realize the explanatory goals.

In Darden and Maull’s original account, integration takes place via the development of inter-field theories, that is, theories that set out and explain the relations between fields. Their model was mainly put forward to account for vertical relations. The concept of inter-field integration however can be easily extended to apply to horizontally-related fields. Since theories are just one of the elements comprising a field, theoretical unification as well as reduction is seen as a local affair that rarely, if ever, culminates in the abandonment of one field in favor of the one where the unifying theory was originally proposed. What happens instead is that new theories that integrate insights from different fields are developed; in some cases, new fields are engendered, but never at the expense of existing ones. The crucial insight of Darden and Maull’s account is to look at how fields become increasingly integrated through the development of theories that explain the relation between them.

In our case, the developments made possible by the D-S model of monopolistic competition have further increased the degree of integration between several fields in economics. The D-S model constituted a powerful vehicle of integration: the same framework/technique was employed with the appropriate modifications in different fields of economics, and for precisely the same purpose, namely to deal with increasing returns at the firm level and imperfect competition. In this perspective, GeoEcon can be looked upon as a new field, or less ambitiously as an interfield theory, which studies the relations between the phenomena of location, trade, and growth partly drawing on insights developed in separate fields. This explains why the fields continue to proceed autonomously in spite of the introduction of new unifying theories. This discussion also brings to the fore what can be thought of as opposing forces towards and against unity: on the one hand, the unifying ambitions of GeoEcon push towards various degrees of unification of phenomena, theories and fields, on the other, the presence of theories whose domains only partially overlap with that of GeoEcon and of fields that continue to proceed at least partly autonomously resist the unificationist attempts.

5 Inter-Disciplinary Unification: Economics Imperialism10

Abrahamsen [1987] identifies three kinds of relations between neighboring disciplines: (1) Boundary maintaining, where the two disciplines pursue their inquiries independently with no or little contact with one another; (2) Boundary breaking, where a theory developed in one discipline is extended across the disciplinary boundaries; and (3) Boundary bridging, where the two disciplines collaborate rather than compete for the same territory. The relationship between economics and geography had traditionally been one of boundary maintaining. Things have changed however with the appearance of GeoEcon. Geographers have perceived GeoEcon as an attempt to invade their own territory. For instance, economic geographers Ron Martin and Peter Sunley [2001, p. 157] confidently claim that “Fine (1999) talks of an economic imperialism colonizing the social sciences more generally, and this is certainly the case as far as the ‘new economic geography’ is concerned.”11 GeoEcon, it is said, has broken the disciplinary boundaries, and has done so unilaterally.

Economics is notorious for its repeated attempts at colonizing the domain of neighboring disciplines. Economics-style models and principles are used to study marital choices, drug addiction, voting behavior, crime, and war, affecting disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, law and political science. The phenomenon of economics imperialism has received a great deal of attention among social scientists: while some celebrate it unconditionally, others despise it. Few philosophers of economics however have entered the debate. This is unfortunate because philosophers have something to contribute in evaluating the benefits and risks of episodes where disciplinary boundaries are broken. This is what the analysis that follows aims to accomplish. If GeoEcon constitutes an instance of economics imperialism, we should ask whether it is to be blamed or celebrated. In other words, the key issue is whether this episode of boundary breaking is beneficial or detrimental to scientific progress.

In a series of recent papers Uskali Mäki [2001; 2009, and Mäki and Marchionni, 2011] has sought to provide a general framework for appraising economics imperialism. The point of departure of Mäki’s framework is to see scientific imperialism as a matter of expanding the explanatory scope of a scientific theory. This aspect of scientific imperialism he calls imperialism of scope. Imperialism of scope can be seen as a manifestation of the general ideal of explanatory unification. If we think of scientists as seeking to increase a theory’s degree of unification by way of applying it to new types of phenomena, it is largely a matter of social and historical contingency whether these phenomena are studied by disciplines other than those where the theory was originally proposed. It follows that whether scope expansion turns into scientific imperialism is also a matter of social and historical contingency. A given instance of imperialism of scope promotes scientific progress only if it meets three kinds of constraints: ontological, epistemological and pragmatic. The ontological constraint can be reformulated as a methodological precept: unification in theory should be taken as far as there is unity in the world. The epistemological constraint has to do with the difficulties of theory testing and the radical epistemic uncertainty that characterizes the social sciences. Caution is therefore to be recommended when embracing a theory and rejecting its alternatives. Finally, the pragmatic constraint pertains to the assessment of the practical significance of the phenomena that a theory unifies.

GeoEcon’s foray into the field of economic geography can be seen as a conse-quence of its pursuit of unification of location and trade phenomena. That some of these phenomena fall within the purview of economic geography should not consti-tute a problem. It is however doubtful that GeoEcon satisfactorily meets the three sets of constraints outlined above. The development of GeoEcon is motivated by considerations of unity among the phenomena (as discussed in the previous sec-tion), but the empirical performance of GeoEcon has not yet been determined and the practical significance of the insights it provides has been questioned (see [Mäki and Marchionni, 2009]).

Rather than being a peculiarity of GeoEcon, it is quite difficult for any economic or social theory to meet those constraints. The consequence is that although per se imperialism of scope is not harmful, it ought not be praised unconditionally, but carefully evaluated. This is more so given that in most cases the forays of economics into neighboring territories implicate other aspects of interdisciplinary relations. Imperialism of scope is in fact often accompanied by what Mäki [2007] calls imperialism of style and imperialism of standing. Imperialism of standing is a matter of academic status and political standing as well as societal and policy relevance: the growth in the standing of one discipline comes at the expense of that of another. Imperialism of style has to do with the transference or imposition onto other disciplines of conceptions and practices concerning what is regarded as genuinely scientific and what is not, what is viewed as more and what as less rigorous reasoning, and what is presented to be of higher or lower scientific status. As John Dupré [1994, p. 380] puts it, “scientific accounts are seldom offered as one tiny puzzle: such a modest picture is unlikely to attract graduate students, research grants, Nobel prizes, or invitations to appear on Night Line.” It is in these circumstances that economics imperialism is likely to trigger the hostile reactions of the practitioners of the colonized disciplines.

A significant component of the worries of economic geographers concerns the standing of GeoEcon and economics more generally vis-à-vis economic geography. The danger, as they perceive it, is that GeoEcon might end up enjoying increasing policy influence just in virtue of the higher standing of economics, and not in virtue of the empirical support it has gained as a theory of spatial phenomena. Similarly, the alleged ‘scientificity’ of economics could give GeoEcon an extra edge in the academic competition, so that the GeoEcon general equilibrium models might end up colonizing economic geography entirely at the expense of the latter’s varied theoretical and methodological commitments.

In the cases Abrahamsen [1987] examines, boundary breaking is typically followed by boundary bridging, namely by the mutual exchange of results and methods. In the case of GeoEcon and economic geography, a number of concrete at-tempts have been made to bridge the boundaries between economists and geographers. Notable initiatives have been the publication of The Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography[Clark et al., 2000], and the launch of the Journal of Economic Geography, platforms explicitly designed to foster cross-fertilization. On the other hand, judged on the basis of patterns of cross-references in leading journals for economic geographers and geographical economists, mutual ignorance seems to remain the prevalent attitude between scholars of the two fields [Duranton and Rodríguez-Pose, 2005]. The presence of these contrasting tendencies makes it hard to predict whether effective bridging of boundaries will take place.

What does this discussion teach economic geographers and geographical economists? That is, how does philosophy help in resolving this heated debate and direct it through more progressive paths? There are two general lessons that are worth taking stock of. The first is that there is nothing inherently problematic in attempting to extend the scope of a theory outside its traditional domain. Disciplinary boundaries are the product of institutional and historical developments, and often have little to do with ‘carving nature at the joints’. GeoEcon is thus given a chance. It is still possible that the spatial phenomena GeoEcon unifies are not in reality so unified, or that the range and significance of the explanatory and practical questions GeoEcon can meet is very limited. All this however has to be established empirically, and not ruled out a priori. Second, GeoEcon and its supporters are recommended to adopt a cautious and modest attitude. If what is exported outside the disciplinary boundaries is not so much a theory, but an allegedly superior research style and/or the higher standing of a discipline, the connection of scientific imperialism to the progress of science is remote at best. The mechanisms sustaining and reinforcing these aspects of the imperialistic endeavor can tip the balance in favor of theories whose empirical support is poor at best. As things stand now, it is not at all clear that there is any warrant for the superiority of GeoEcon vis-à-vis alternative theories in the existing domain of spatial phenomena. The worries voiced by economic geographers are therefore to be taken seriously. Here again we can see at work forces towards as well as forces against unification. On the one hand, GeoEcon pursuit of unification generates pressures on disciplinary boundaries, on the other, economic geographers have refused to accept GeoEcon, and in spite of attempts at bridging the boundaries, the two fields continue to proceed in mutual ignorance of each other’s work.

6 Unrealistic Assumptions, Idealizations and Explanatory Power

Economic geographers also complain that the highly stylized unrealistic models of GeoEcon cannot capture the complexity of real-world spatial and geographical phenomena, and hence cannot provide explanation and understanding of those phenomena. Although in some cases particular unrealistic assumptions are blamed, some geographers argue against the practice of theoretical model building altogether.

The role, function and structure of theoretical models in science are topics of wide philosophical interest.12 Despite disagreements on several aspects of scientific modeling, recent philosophical literature appears to converge on the view that unrealistic models, in the social sciences and economics too, play a variety of important heuristic and epistemic functions. Here I organize the discussion around two themes that specifically arise in the context of GeoEcon models and their reception in neighboring disciplines. One concerns the problem of false assumptions in theoretical models, and the other has to do with the kind of explanations theoretical models can afford. I draw on recent philosophical literature to provide a qualified defense of the GeoEcon theoretical models against the criticisms that geographers have leveled against them. It is important however to bear in mind that nothing in what follows implies the truth of the GeoEcon’s explanation, let alone its superiority vis-à-vis theories of economic geographers. This is an empirical issue and the empirical evidence gathered so far does neither support nor reject GeoEcon. The defense of GeoEcon has thus to be read in terms of a potential to generate explanations of real-world spatial phenomena. The lesson, which I take to be generalizable to analogous disputes, is that there is nothing inherently problematic with explaining the world via unrealistic theoretical models, and the parties in the dispute do better to focus on the empirical and practical performance of genuinely competing theories than on the wholesale rejection of each other’s methodologies.

6.1 Galilean idealizations and causal backgrounds

Disputes over the unrealisticness of models and their assumptions abound in economics and neighboring disciplines. These disputes often centre on the question of whether a given model (or a set of models) is realistic enough to explain the real-world phenomena it is supposed to represent. Economic geographers have forcefully complained that the GeoEcon models contain too many unrealistic assumptions. More pointedly, GeoEcon is held to ignore the role of technological or knowledge spillovers, to treat space as neutral and assume identical locations, to pay too little attention to the problem of spatial contingency, and to overlook the possibility that different mechanisms might be at work at different spatial scales. Critics of economics, including some geographers, typically depict economists as subscribing to the Friedmanian idea that unrealistic assumptions do not matter as long as the models yield accurate predictions, and hence typically interpret the economists’ models instrumentally.13

Philosophers of economics have made it clear that such characterizations do a poor job in depicting the practice of model building in economics. The presence of unrealistic assumptions per se does not pose problems for a realistic interpretation of the models. Instead, it is precisely thanks to the presence of these unrealistic assumptions that models are capable to tell us something about the real world (see [Cartwright, 1989; Mäki, 1992]). One way to take this idea across is to compare theoretical models to controlled experiments [Mäki, 2005; Morgan, 2002]. Both controlled experiments and theoretical models isolate a causal mechanism by way of eliminating the effects of those factors that are presumed to interfere with its working. Whereas experiments do so by material isolations, theoretical models employ theoretical isolations [Mäki, 1992]. Theoretical isolations are effected by means of idealizations, that is, assumptions through which the effect of interfering factors is neutralized. Following McMullin [1985], let’s call this species of assumptions Galilean idealizations in analogy to Galileo’s method of experimentation.

Not every unrealistic assumption is of this kind, however (see for example [Mäki, 2000; Hindriks, 2006]). A substantial portion of unrealistic assumptions of economic models is made just for mathematical tractability. Since the problems of and justifications for the latter kind of assumptions deserves a discussion of their own I will come back to them below. First I would like to spend a few words on Galilean idealizations and illustrate their role in GeoEcon models.

Both controlled experiments and theoretical models are means to acquire causal knowledge. They typically do so by inquiring into how changes in the set of causal factors and/or the mechanism that is isolated change the outcome [Woodward, 2003]. Because of this feature, contrastive accounts of explanation [Garfinkel, 1980; Lipton, 1990; Woodward, 2003; Ylikoski, 2007] fit the way in which both models and laboratory experiments are used to obtain causal and explanatory knowledge. Briefly, contrastivity has it that our causal statements and explanations have a contrastive structure of the following form: p rather than q because of m.14 This implies that the typically long and complex causal nexus behind p is irrelevant except for that portion of it that discriminates between p and q, what I referred to as m. The whole causal nexus except m constitutes the causal background, which is shared by the fact and the foil.15 As Lipton [1990] proposes, in order for a contrast to be sensible, the fact and the foil should have largely similar causal histories. What explains p rather than q is the causal difference between p and q, which consists of the cause of p and the absence of a corresponding event in the history of q, where a corresponding event is something that would bear the same relation to q as the cause of p bears to p [Lipton, 1990, p. 257]. In other words, to construe sensible contrasts we compare phenomena having similar causal histories or nexuses, and we explain those contrasts by citing the difference between them. It is the foil then that determines what belongs to the casual background. The choice of foils is partly pragmatic, but once the foil is picked out, what counts as the explanatory cause of p rather than q is objective.

In the case of theoretical models, the shared causal background is fixed by means of Galilean idealizations. That is, everything else that is part of the causal nexus of p and q, except the explanatory factor or mechanism m that we want to isolate, is made to belong to a shared causal background [Marchionni, 2006]. Once the shared causal background has been fixed via idealizations, the kind of causal and explanatory statements we can obtain from a given theoretical model becomes an objective matter. In other words, the kind of mechanism we want to isolate determines what idealizations are introduced in the model, which in turn determine the kind of contrastive questions the model can be used to explain. This means that the explanation afforded by theoretical models depends on the structure of the theoretical models themselves, that is, by what has been isolated as the explanatory mechanism and what has been idealized to generate the shared causal background.

To illustrate, consider the CP model of GeoEcon. The model focuses on the effects of the mechanism of pecuniary externalities on the emergence of a core periphery pattern. Its result is that the emergence of a core-periphery pattern depends on the level of transportation costs, economies of scale, and the share of manufacturing. As economic geographers have been ready to point out, the CP model ignores a host of determinants of real-world agglomeration. For instance, locations in the CP model are assumed to be identical, which is clearly false of the real world. Among other things, they differ in terms of first-nature geography such as resource endowments, climate, and geography. A full answer to the question of why manufacturing activity is concentrated in a few regions would include the causal role of first-nature geography (and much more, such as the effects of knowledge spillovers, thick labor markets, social and cultural institutions etc.). Geographical economists by contrast regard the assumption of identical locations as desirable: “One of the attractive features of the core model of geographical economics is the neutrality of space. Since, by construction, no location is preferred initially over other locations, agglomeration (a center-periphery structure) is not imposed but follows endogenously from the model” [Brakman et al., 2001, p. 167]. By assuming identical locations, first-nature geography is fixed as causal background that is shared by the fact, agglomeration, and the foil, dispersion. Agglomeration (or dispersion) then results exclusively from the interactions of economic agents (second-nature geography).16 The assumption of identical locations serves to create a shared causal background where the only difference in the causal nexuses of agglomeration and dispersion lies in the parameters that determine whether centrifugal or centripetal forces are stronger. The shared causal background determines the kind of explanatory questions the CP model can be used to answer. For example, it can explain agglomeration in either of two locations in contrast to uniform dispersion but not agglomeration in one location in contrast to agglomeration in another. To explain agglomeration in contrast to different foils, we must construe models that fix the shared causal background differently from the CP model and that allow us to see how the new isolated mechanism (or set of factors) explains the new contrastive explanandum.

In general the contrastive perspective on the role of unrealistic assumptions in theoretical models proves valuable for the following reasons. First, the affinity between theoretical models, causal knowledge and explanation comes out with significant clarity. The presence of a causal background is not a feature peculiar to theoretical models, but it is part and parcel of our causal and explanatory activities. It is common to all our causal and explanatory claims, independently of how they have been arrived at and how they are presented. Second, a contrastive perspective on theoretical models makes it easy to judge what a model can and cannot achieve in terms of potential explanation; misjudgments of explanatory power are often due to misspecification of the contrast. One of the charges of economic geographers against the CP model is precisely that it cannot tell where agglomeration occurs. Here contrastivity helps to see why this charge is at once justified and misplaced. It is justified because in fact by assuming identical locations, GeoEcon cannot account for the contrast between agglomeration in one location rather than another. But it is also misguided because to investigate why agglomeration occurs in some locations and not in others requires the construction of a different causal background than the one featured in the CP model. Finally, contrastivity also sheds light on how and why relaxing assumptions that fix the causal background affect the kind of causal and explanatory claims a theoretical model can afford. In recent GeoEcon models, the original assumption of identical locations has been relaxed, thereby modifying the extension of the causal background. As a result, a new set of contrasts become potentially available for explanation within the GeoE-con framework. More complicated models can be seen as having narrower causal backgrounds, but we should not be misled by this into thinking that there is a continuous progression towards ever more realistic models. There is no such thing as a fully realistic model, and there is no causal or explanatory statement without a background causal field. I will have more to say about this aspect of theoretical models in Section 6.3.

6.2 Tractability and robustness

Not all assumptions directly serve to theoretically isolate the mechanism of interest. Many assumptions of economic models are there to make the theoretical model tractable so as to obtain deductively valid results. Let’s call them tractability assumptions (Hindriks 2006). Tractability assumptions are false, and the knowledge available at a given point in time does not say how they can be relaxed. Consider once more the CP model. A number of its assumptions are explicitly made in order to obtain a mathematically tractable model. Without them, no neat conclusion about causal and explanatory dependencies is forthcoming. For example, transportation costs in the CP model are assumed to be of the iceberg form, meaning that of each unit of the good shipped only a fraction of it arrives at destination. Tractability also determines the form of the utility and production functions. The CP model assumes constant elasticity of substitution, which is a very specific and unrealistic assumption to make. It is telling that geographical economists themselves refer to them as ‘modeling tricks.’ The unrealisticness of these assumptions is far more problematic than that of Galilean idealizations. The point is that at a given point in time there may be no way to substitute these assumptions with more realistic ones while keeping the rest exactly the same. In many cases, the most we can do is to construct models that include different sets of unrealistic assumptions. Cartwright [2007] claims that tractability assumptions provide the most reason for concern. But how do economists deal with them in practice?

They deal with them by checking the robustness of their modeling results with respect to changes in those modeling assumptions. Kuorikoski, Lehtinen and Marchionni [2010] propose to understand this practice as a form of robustness analysis, intended as Wimsatt [1981] does as a form of triangulation via independent means of determination (see also [Levins, 1966; Weisberg, 2006a]). On this view, the practice of economics of construing models where just one or a few assumptions are modified acquires a crucial epistemic role. The purpose of robustness analysis is in fact to increase the confidence about the reliability of a given result; in other words, that a result is robust across models with different sets of unrealistic assumptions increases the confidence that the result is not an artifact of a particular set of unrealistic assumptions. In addition, robustness analysis serves to assess the relative importance of various components of a model, or of a family of models.

Much of model refinement in GeoEcon can be seen as checking whether the main results of its core models (the CP and the VL models) are robust with respect to changes of unrealistic assumptions. Two main cases follow from this procedure. First, the results are found to be robust to different sets of unrealistic assumptions. For instance, models subsequent to the CP model find that the dependency between the level of transportation costs and agglomeration is robust to changes in specifications of functional forms and transport technology. This increases the confidence that the CP result does not crucially depend on particular false assumptions. Instead, it increases the confidence that the results depend on those elements that are common across models, that is, those elements that describe the isolated causal factors or mechanism. In GeoEcon, this is the mechanism of pecuniary externalities.

The second case is when the results of the model break down. One of the functions of robustness analysis is to help assess the relative importance of various components of the model. Thus, it is also employed to see how changes to the background causal field impact on the results of the model. In [Kuorikoski et al., 2010] we discuss examples in which additional spatial costs are included in the model. If a different set of tractability assumptions yields a different result, then this can mean either of two things. It can indicate either that the particular assumption had implications for the causal background that were not recognized or that the results are artifacts of the specific modeling assumptions.

Obviously I do not want to claim that robustness analysis resolves all the epistemic difficulties that unrealistic theoretical models present us with, or that it solves all the difficulties of GeoEcon. For one, robustness analysis in GeoEcon displays conflicting results, which still needs to be reconciled. More generally, the number of unrealistic assumptions of economics models is very large, and many of these assumptions are rarely if ever checked for robustness. And even if that were done, the problem of determining the truth of a reliable result, which ought to be done empirically, would still remain.

6.3 The explanatory power of theoretical models

Scientists and philosophers alike quite commonly talk about explanatory power as if it was a clear concept, but unfortunately it is not. Philosophical literature on this issue is quite scarce, and surprisingly so given the extensive use of ideas like explanatory power, explanatory depth and the like (much of what I discuss below are advancements of Marchionni [2006; 2008].17 In clarifying the notion of explanatory power, either of two strategies can be adopted. The first is to advance a preferred account of what explanation is and to derive a notion of explanatory power from it. The second strategy is pluralistic and admits the presence of different dimensions of explanatory power that different explanations have to different degrees. I prefer this latter strategy because I believe it permits to illuminate more about the way in which scientists judge scientific theories and models. In different scientific contexts, different dimensions of explanatory power are valued more than others and this is why so many disagreements arise about the potential for explanation of models and theories. Adopting this somewhat pluralistic stance however does not mean to give up the idea that there is one particular feature that makes something an explanation. We can for instance adopt a contrastive theory of explanation and hold that adequate explanations are answers to contrastive why-questions that identify what makes a difference between the fact and its foils.

In what follows I do not pretend to offer a well-worked out theory of the dimensions of explanatory power, but rather wish to present together a few ideas that are scattered in the literature and can supply the building blocks of such a theory. In particular, I examine three dimensions of explanatory power: contrastive force, depth and breadth. Since theoretical models are the means whereby GeoEcon, and economists more generally, provide explanations, I will bring these dimensions to bear on features of theoretical models (but many of the observations I propose can easily be extended to theories).

The first dimension I consider is contrastive force. Contrastive force directly connects to the previous discussion on unrealistic assumptions, contrastive explanation and causal backgrounds. To my knowledge, Adam Morton [1990; 1993] has been the first to employ the idea of contrastive explanation to evaluate the potential explanatory power of theoretical models. Morton [1993] argues that false models have quite restricted contrastive force, in the sense that they address some contrastive questions about p but not others. Morton’s example is of a weather model, a barotropic model, which assumes wind velocity not to change with height. This model can be used to explain why the wind backs rather than veers (given suitable conditions), but cannot explain why the wind backs rather than dying away. The degree of contrastive force constitutes an obvious dimension on which to judge the explanatory power of theoretical models. Although false models in general can be expected to have very limited contrastive force, there is some room for variation (see also Marchionni 2006). As I show above, GeoEcon’s exclusive focus on a certain kind of economic mechanisms (pecuniary externalities) limits the range of contrastive questions about agglomeration it can address, as for example, it cannot tell where economic activity agglomerates or why firms agglomerate rather than join into a single larger firm.