In peace-time doctrine and in maneuvers, bomber formations were used almost always without fighter escort. The range of SE fighters did not fit into the plans for strategic bombing. About the years 1937/38, it was resolved to build twin engine fighter units for these purposes, called Zerstorer units.

In Spain, the necessity was recognized of furnishing fighter escort for bomber formations by day wherever enemy fighter action was to be reckoned with. The introductions of the so-called fast bombers, the Do. 17 and the He.111 did not alter the situation. The Russian and other Republican forces at the time also used fighter escort for their bomber missions, by day.

In Luftwaffe circles in Germany at the time arose a mental conflict, because in maneuvers the Do. 17 and the He.111 were being used, while the fighters were still using the Arado 65 and 68 and the Heinkel 51, which were old slow fighters. In this way the impression arose that the bomber of the future would apparently be faster than the fighter of the future. Experience in Spain with the introduction of the Me.109 soon corrected this wrong impression. As a result, steps should have been taken to bring the range of the SE fighter aircraft up to that of the bombers and thus to conduct the strategic air war as a cooperation of bombers and fighters by day. This step was, however, not taken. It was maintained instead that the twin-engine fighter (Zerstorer) was an aircraft equal to or better than the modern SE fighter, to compete on even terms. In practice, the Me.110 was able to perform adequately in Poland and France. In the Battle of Britain they suffered the already frequently predicted defeat.

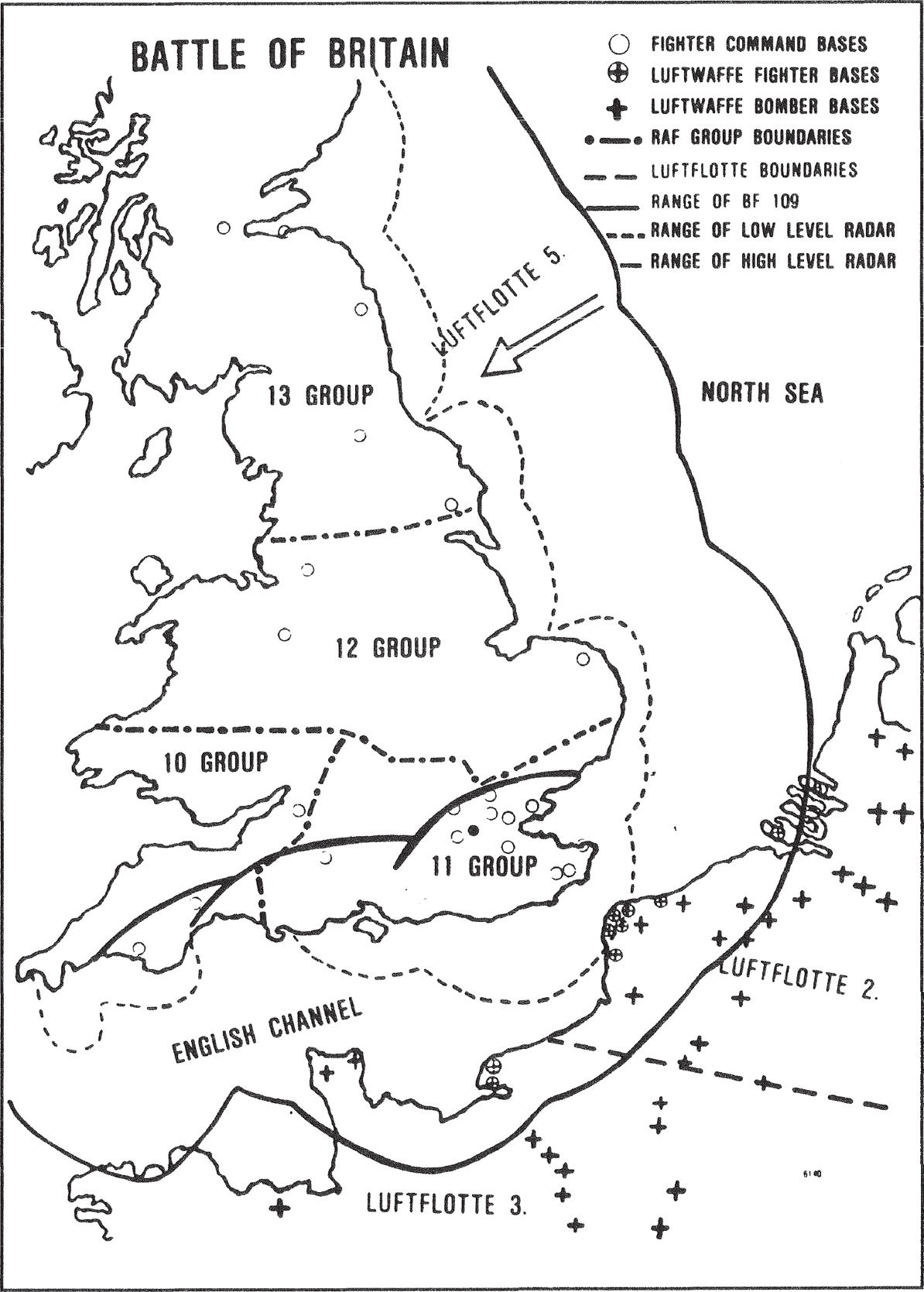

Starting in the Battle of Britain the conduct of escort missions was accordingly the exclusive function of the SE fighter, whose inadequate endurance and range worked decisively against it. It was still believed that the deficiencies of the twin-engine fighter could be remedied by better technical performance. This thought led to the construction and series production of the Me.210, which later was developed into the Me.410. Entirely apart from their failures in design and in construction the performance of these aircraft would never have been sufficient against modern SE fighters. The only possible result should have been the raising of the range of the SE fighter. Until the introduction of the drop tank, nothing was done along these lines. On the contrary, the range of the Me.109 on its interior fuel tanks continually declined from the greater consumption of the continuously improved and more powerful engine.

Operationally, the following types of escort are:

(a) Close Escort

(b) Escort Cover

(c) Sweeps to clear the approach and target areas.

(d) Combined escort by SE and TE fighters

(a)Close Escort was conducted by SE and TE fighters, whose units were assigned to protect certain bomber formations. Fighters were divided into Rotten (two’s) or at least into Schwarme (four’s). They protected the bomber formation against close attacks from ahead, behind, above, right and left. It was strictly forbidden to let air battles tempt the fighters away from the immediate vicinity of the bombers.

The difficulties and weakness of this type of escort lie in its purely defensive character. Where enemy attacks are energetically led, this type of protection cannot be effective, because the available time and tactical possibilities for the escort are always less than for the interceptors. A further difficulty lay in the slow speed of the heavily loaded German bombers, which was much lower than the best maneuvering speed of the fighters. The result was that the fighters had to follow the bombers by continually turning and changing altitude.

Nevertheless, even this type of incomplete escort always satisfied the bombers. Anything that took place out of his immediate vicinity did not interest the bomber man, although a roving escort was a prerequisite for keeping enemy fighters at a distance. The demands and complaints of the bomber men thus always materially injured the carrying out of the escort mission.

In this discussion it is not forgotten that only a part of the fighter units concerned carried out their difficult jobs with the necessary exact discipline. The cooperation was especially good when certain bomber units could work for a long time together with certain fighter units so that both could work out and compare their opposed interests and demands.

For a considerable time – before the Battle of Britain – the TE fighters were able to conduct successfully this close escort alone. Later the weakness of the TE fighter and the recognition and exploitation of this weakness by RAF fighters became so serious that the TE fighters could no longer escape from aerial combat but were forced always to take purely defensive measures, like the defensive circle (Lufbery). From this time onward the TE fighter (Zerstorer) could no longer be counted on for escort missions; instead the TE fighter itself required fighter escort and increased the escort burden of the SE fighters.

When individual damaged bombers left formation because of technical trouble or because they were shot up, it was the job of the close escort to provide special cover for the imperiled aircraft. It is clear that close escort as a purely defensive tactic cannot be successful against a strong and energetically led fighter attack. Close parallels can be drawn between the conduct of German escort in 1940 and the first missions of American fighter escort over Europe. After repeated demands of German formation leaders it was decided to use simultaneously a close escort and an escort cover.

(b)Escort Cover was conducted by Staffeln or weak Gruppen. During the escort of the bombers the escort flew about 3000 to 6000 feet higher, off to the side. Their mission was to attack approaching enemy fighter formations before they were in an attack position. The escort was supposed to combat enemy fighters until they were at least temporarily unable to attack the bombers effectively. They were then required immediately to resume contact with the bombers and continue escort cover. They were also required to help the close escort should enemy fighters effect a surprise and break through to the bombers from front or below. In any event, the escort cover had to remain with the bombers on the way in to the target and out again.

The strength relationship between close escort and escort cover varied according to the strength of the bomber formation to be escorted, and the strength and formation size of the fighter opposition expected. It was usually about 1 to 1. Bombers, close escort and escort cover were linked by a common R/T frequency. This was first achieved in the Battle of Britain by retrofitting radio equipment into aircraft already operational. Very signals and smoke signals have not proved of value except to show the colors of the day.

In special situations the escort cover can be released on the way home and strafe ground targets. This can only be done when it is known with confidence that no further contact with enemy fighters is to be expected. The success of a close escort mission or of an escort cover mission depends exclusively upon how well the bombers are protected, that is to say, upon the losses suffered by the bombers. The escort fighters’ victories are less important and of secondary interest. This should be taken into consideration in evaluating the success of missions.

(c)Sweeps to clear the approach and target areas are desirable if sufficient fighter strength is on hand. This can be especially successful if the strength and conduct of the enemy fighter defense is known with some exactness. The sweeping force must be on the approach route and over the target at the proper time ahead of the bombers, engage every enemy fighter formation, break it up, or at least keep it away from the bombers. In such cases, the escort cover can frequently enter temporarily into the fight. The formations of the sweeping forces must try with determination to press on into the target area despite intervening air combat. The departure from the target area can only proceed after bombs are away and a rear cover is provided for formations of pursuing enemy fighters. The mission of the fighter sweeping force is to shoot down the enemy and keep as many enemy fighters as possible away from the bombers. In practice this type of mission is the most fruitful and therefore the most popular.

This type of operation was completely mastered from the middle of 1944 by American Mustang fighters on escort duty. German escort fighters in the Battle of Britain in 1940 suffered seriously from their short endurance and resulting short range. Rendezvous with the bombers could take place only right on the Channel coast and had to be completed in a very few minutes; no delay could be allowed the bombers and the flight to the target could only be effected over the shortest possible route. If anything irregular happened, the fighters could not return after the mission to their place of start, but had to land on the beach or in the water for lack of fuel.

Jettisonable fuel tanks were not introduced until after the Battle of Britain. This temporary limitation on the use of fighters resulted in preventing the forming of large bomber streams; instead the bomber Geschwader had to fly in to the target or targets in small string formations. This was repeated in every mission. Variations and resultant surprises for the RAF did not exist. The points and times where the various bomber formations crossed the coast and rendezvoused with their respective fighter formations were so close together in time and place that the fighters frequently rendezvoused with the wrong bomber formation, with the result that other bomber formations were covered insufficiently or not at all. This became especially frequent when the weather began to get bad in autumn 1940 and rendezvous points and times could no longer be held on top of the clouds. Moreover, the defensive firepower and resistance to hits of the Do.17 and the He.111 would not stand comparison with the qualities of four engine American bombers. Radar navigation and fighter control procedures were not yet available for the German side. The cumulative effect of all these circumstances, and not a weakening of the German fighter formations, led to greater bomber and fighter losses. The advent of bad weather also caused excessive losses. When it was decided to attack important targets which were completely beyond the range of the fighters, the Luftwaffe had to resort to night attacks.

On the southern front and especially in the Battle of Malta the German fighter forces were numerically so weak that the effective conduct of escort missions according to the above points was not possible. A compromise of the various types of escort was therefore improvised as the situation and possibilities permitted. At the same time that the attacks on Malta resulted in more and more losses because of the ever stiffening fighter defense, the fighter escort for transport aircraft over the Mediterranean was doomed to failure in the face of meager fighter forces and heavy enemy fighter action. No new tactical points were brought up here anyway.

The air war on the Eastern Front developed in the course of the years to an ever higher standard of technical achievement and tactics. The increased use of the German forces for strategic bombing operations would no doubt have speeded up this development. As it was, fighter escort for bombers was carried out in the most primitive form. A few fighters would attach themselves to the bomber formations as they passed over the fighter fields and escort them to the target and back, as far as the front, when the fighters usually broke off and engaged in fighter sweeps. The Russian fighters usually refused to attack even the lightly armed German bombers, mainly because they had not mastered the tactic of a disciplined attack. Usually the German bombers were attacked only by courageous Russian lone wolves, who dived daringly and cleverly onto the bombers. The German fighter escort was therefore a combination of close escort and escort cover, and fighter sweeps were flown after a completed escort mission.

For attacks and raids on the tactical area (battle area), the number of escort fighters was usually less than that of the bombers. Only raids of great penetration range were flown with a number of fighters equal to the bombers. Radar service and fighter control were not at first available in Russia, and the later introduction of these things did not bear much fruit because of the repeated retreats. Only the Listening Service always furnished useful service on the Eastern Front. The supply and support missions of the Luftwaffe for surrounded areas and cut-off forces (Stalingrad Demyansk, Crimea, Cholm, etc.) put the fighter arm to very difficult tasks. If supply landing fields were available, part of the fighter escort landed with the transport aircraft, in order to furnish cover as soon as the transports started back. For the most part, however, four-fifths of the fighter combat on the Eastern Front took place over the battle area in support of the Army.

Ju.87 dive bomber units were largely manned by fighter personnel when they were set up. They therefore took on a special character which was always more closely related to the fighter arm than to the bomber arm. Outmoded in performance, slow in level flight and also in dives, inadequately armed both from the front and rear, the Ju.87 soon had to quit the Battle of Britain and the anti-shipping war. When German air superiority in Africa was lost the Ju.87 could not be employed without heavy losses even in the presence of fighter cover. On the Eastern Front, use of the aircraft was possible until the end of the war, with the losses from Russian fighters being less than those from ground defenses. In some respects the Ju.87 was the counterpart of the Il-2 used by the Russians.

The most conspicuous weakness of the Ju.87 formations lay, however, in their impossibly low formation flying speed of about 250 km per hour. The operational altitude of the Stuka in the Battle of Britain was about 16,000 feet and lower. In Russia they flew at about 6500 feet. Pull-out altitudes were set according to targets and ground defenses. The minimum pull-out altitude was about 1900 feet. On the Eastern Front the Stukas almost always went over to ground attack tactics after their bombing dive.

The single basic difference in the conduct of escort for Stukas (Ju.87’s) compared to ordinary bombers is the special need for protection during the dive and during the re-assembly after the pull-out.

In practice this was accomplished by a part of the close escort. This was best done by the escort cover arriving at the pull-out altitude shortly before the Stukas and patrolling there. This pull-out altitude must be determined in advance in the field order. In case it is altered, all elements must be notified by R/T. The other part of the close escort dives with the Stukas, but because of greater diving speed this escort must resort to turning to hold position. A special danger exists from the time of the pull-out until the re-closing of the Stuka formation. It is not possible in this period for the fighters to protect each individual Stuka. Therefore it is the Stukas’ responsibility to keep formation at least in Ketten (3s) and to get as quickly as possible into closed formation. When they had to dive through cloud, or when the pull-out altitude was clouded in, this coordination did not work and losses resulted.

Influenced by the concepts of pre-war times, German medium bombers like the Ju.88 and Do.217, even the heavy bombers like the He.177, had to be fitted for dive bombing attacks. Greater accuracy was supposed to be obtained by this. The disadvantages of this requirement were, with the exception of dive bombing against shipping, so great that the concepts must be now regarded as false. For the fighter arm, however, it did mean an aggravation of the job of escorting, first because of the diving itself and second because of the weak defensive armament of the bombers. As early as the Battle of Britain, the Ju.88 formations gave up dive bombing and went over to high altitude level bombing. As long as dive attacks were conducted, the fighters flew escort according to the principles laid down. Because of the inferior maneuverability of the Ju.88 compared to the Stuka, the dive and pull-out of the Ju.88 formations were even more spread out and the re-assembly took more time than with the Ju.87’s. The Do.217 and the He.177 were practically never employed by day on dive bombing missions.

One important fact for the escort of Stukas is that the Stuka is very slow and vulnerable, therefore, rendezvous with the escort must be carried out with great certainty. In Africa, where during most of the campaign the threat of enemy fighters behind the German lines was not great, the following method of rendezvous proved to be good: For example, the Stukas flew over the fighter field at 6000 feet at 1500 hours. The fighters were ready in their air-craft on cockpit alert (Sitzbereitschaft) at 1455 hours. As soon as the Stukas appeared over the field, the fighters got the order to start. The Stukas flew on to the front and the fighters caught up. In this way, rendezvous was both sure and economical as far as fighter fuel was concerned. This type of rendezvous is, however, only possible where enemy forces are not strong enough to fly over the front. At the target it was important that a portion of the fighter escort dive with the Stukas (or fighter-bombers, or ground attack air-craft) to cover their most vulnerable moment as they pulled out of the dive. Radio communication between the fighters and the bomb-carrying aircraft proved well worth while. Radio silence is extremely important, especially when other formations are sighted. It is easily possible that a false sighting of enemy fighters will take place and the bomb carrying aircraft will jettison their bombs unnecessarily. Only the most experienced pilots and formation leaders should be allowed to announce the approach of enemy aircraft.

For missions of tank-destroying aircraft it is often advisable during the attack for the fighter escort to shoot up A.A. installations in the vicinity, to remove this greatest danger for the tank-destroyers.

In Spain, ground attack missions at low level were flown exclusively without fighter cover. If fighter opposition developed, the He. 51 formations were able to defend themselves. The Legion Kondor fighter Staffeln, however, often entered the front area at the same time as the ground attack Staffeln and gave indirect escort by flying fighter sweeps in the general area. For operations against enemy airfields farther to the rear, a common time of arrival over target was given both fighters and ground units. No case is known to Galland, however, where actual immediate fighter cover was furnished for ground attack units in Spain. In the Polish campaign ground attack units with the slow Henschel 123 bi-plane operated completely without fighter escort.

In the French Campaign, in 1940, similarly, no fighter escort was flown for ground attack units. Fighter units were regularly sent in to sweep clear the combat area for the ground attack formations. Only one ground attack (Schlachtflieger) unit existed at this time, II/ (Schlacht) Lehr Geschwader 2, which was attached to Fliegerkorps VIII (Richthofen’s tactical air force) and was equipped with the Henschel 123 bi-plane. After the campaign in France, this Gruppe re-equipped with the Me. 109 fighter-bomber and was in combat together with Kampfgruppe 210 in the Battle of Britain. The missions which these two Gruppen flew in the Battle of Britain were not ground attack missions, but fighter-bomber missions. They were, of course, flown under fighter cover, because of the strong RAF fighter defense.

The Campaign against Russia was begun in 1941 with the single ground attack Gruppe, II/(Schlacht) Lehr Geschwader 2, which at the time had variously three Staffeln of Me.109’s and one Staffel of Hs.123’s, or two of Me.109s and two of Hs.123’s. In any event, the Gruppe needed no fighter cover, furnishing its own cover with the Me.109s. One other Staffel of the Gruppe was at this time being equipped with the Henschel 129, which was used more and more. Later these Hs.129 Staffeln specialized as tank-destroyers with the MK 101 cannon.

The setting up of two more ground attack (Schlacht) Geschwader in early 1942, with Me.109’s and Me.110’s, brought new demands for fighter cover. In II/ (Schlacht) Lehr Geschwader 2, fighter cover was still furnished by the Gruppe itself. Even the tank-destroying Hs.129’s, attached to the newly created Schlacht Gruppen, were covered during missions by fighter aircraft, Me.109s and Me.110s.

It frequently occurred that for concentrated offensives twin-engine bombers, Stukas, and ground attack units operated in uninterrupted succession, in the same area, for example, where a break through had occurred. For this period of massed activity, the area concerned was covered by an air umbrella of all fighters available not being used for the immediate escort of the bombers and Stukas.

Later, some Henschel 129 tank-destroyer Staffeln were attached to fighter Geschwaders to provide a striking force with heavy fire power for use against Russian tank breakthroughs. Because of the lack of Hs.129’s this experiment was stopped. In addition, in Summer 1943 an operational concentration of all the Hs.129 tank-destroyer units was attempted. The use of the tank-destroyers en masse resulted in several successes. During this period, fighter escort for the Hs. 129’s was furnished by a fighter Gruppe especially subordinated to the tank-destroyers for this purpose. This was one of the few cases in which a sub-ordination of fighters for such cooperation was successful. For this special purpose it was worthwhile.

Starting in 1943 the ground attack units (Schlachtverbande) converted to F.W.190’s. Right after this the Stuka Gruppen began their conversion from Ju.87’s to F.W.190s and became not only nominally but also actually ground attack units (Schlachtgruppen). Fighter cover was not provided for them, however, except in special cases. For the purpose of protecting these ground attack units from enemy fighters, the chief method employed was the sweeping clear of the battle area by regular fighter units. Only the few remaining Stuka units required an actual fighter escort. No further alterations or developments occurred until the end of the war.

In Africa there were first one and later two ground attack units with F.W.190’s. Operations were only possible with a ratio of escort to escorted aircraft of 1:1. With increasing Allied air superiority in Tunis, Sicily, and Italy their operations became more and more difficult and losses heavier. A single Hs.129 tank-destroyer Staffel which was in the Southern theater could not be used operationally at all and was transferred to the Russian front.

In June 1944 one ground attack unit was used on the invasion front, and it required strong close escort. Allied air superiority soon made the use of ground attack units impossible. No operational order could be carried out on time, since the Allied fighter umbrella hung almost continually over the fighter bases. Assemblies and rendezvous in the air were knocked to pieces or never even allowed to start. At the latest, on the way to the target area the formations of ground attack aircraft and fighter escort were engaged in combat with numerically superior enemy forces. Under such an oppressive enemy air superiority every type of planned mission was brought to a halt. Only in those surprise missions like the attack on Allied airfields on 1st January 1945 could anything be accomplished by the personal initiative of the immediate formation leaders. In conjunction with the air superiority of the Allied fighters and their good fighting spirit and ability, the Allied radar and fighter control organization deserves special mention. They succeeded in grasping every German air operation immediately.