In addition to the usual points which concern all types of units, the following points are especially important for ground attack units:

(1) The operations room must be as close as possible to the landing field in order at all times to be able to overlook the field and dispersal areas and to supervise the start and landing procedures. If the enemy has air superiority and frequent strafing attacks on the field take place, this practice can be left out. The disadvantages of lengthening the readiness times and the increased uncertainty of the wire signals network are the results.

(2) Especially important were the immediate and adequate developments of signals facilities. A telephone exchange and radio station were essential for every Gruppe. The telephone exchange must have the following connections, directly if possible:

(a) to the superior unit

(b) to all inferior units

(c) to the radio room

(d) to the units’ radio beacon D/Fing station and the Egon control station Besides this, the units’ headquarters were combined or linked with its own radio station for communication with the formations in the air and with any unit of the ground which kept an air situation plot (like a fighter Gruppe); if possible the headquarters was physically connected with these facilities, not just by wire.

On airfields which were not yet outfitted with signals facilities, a radio-room equipped Ju.52 transport aircraft was used, obtained from Fliegerkorps or Luftflotte.

All wire communications were supplemented by radio or courier communication for certainty of contact.

(3) Intelligence Service. The main effort of the work here lay in a painfully exact keeping of the enemy situation and in the immediate receiving and evaluating of the smallest reconnaissance reports.

In addition the supplying of the unit with sufficient maps, air photos, photo maps and map sketches of the local frontline area is an important function of the intelligence officer.

(4) Operations Officer. For the operations officer the main job was keeping the friendly situation map. He had to strive especially hard to keep up with the latest developments as to the locations of the front lines.

(5) Meteorological Service. For ground attack units, the local weather situation and the short range prediction were of special interest. The large weather picture and long range predictions were unimportant. Since the facts needed for ground attack missions could usually be supplied by the meteorologists of the airfields or from superior units, the meteorologist originally with the staff of the Geschwader was superfluous, and his place in the TO was therefore cancelled. It was different, however, with the night ground attack units. These units were, as a result of their usual equipment of radio and navigation devices, both in the air and on the ground, especially dependent upon a short exact weather forecast. Since they were usually not based at good airdromes, but on small field landing grounds with poor wire connections to higher units, every night ground attack unit had a weather man. It was his job to keep close track of the weather during missions and warn the aircraft on operations of sudden fog, or other worsening of the weather.

(1) Wherever possible, a preliminary order with statements of bomb load and times of readiness (for example, short readiness of 20–30 minutes, or one hour readiness, etc.) was given. When short readiness was ordered, the Staffel CO’s usually stayed in the operations room to be informed as soon as the final operational order came in.

(2) The order was relayed verbally with the use of a map. It contained as a rule the following items:

(a) Friendly and enemy situation on the ground and in the air.

(b) Friendly intentions.

(c) Mission.

While the items (a) and (b) remained standing without additions, the item

(c) Mission was enlarged upon by the unit CO as follows:

Bomb Load with fusing

Take-off Sequence

Assembly

Formation

Flight in to the target (route, altitude, point for crossing the front)

Time and duration of attack

Conduct of attack (dive, shallow dive, low level, bombing and strafing)

Assignment of targets (The aircraft which were to keep down enemy A.A. and to take over fighter escort if no special escort was provided)

Flight Back – (manner of assembly, route, and altitude)

Radio (call signs, conduct of internal communications, for example, ‘radio silence on the whole approach until the front is crossed’. Cooperation with ground control.

Fighter Cover – (If it is provided, rendezvous point and manner of flying which is arranged by the unit CO with the fighter CO)

Navigation (Dividing up the route according to time and space; navigation aids, traffic with Egon stations or radio beacons) Weather situation Naming of deputy CO

Out of this mass of items, those which usually repeated themselves could be omitted, since they were common knowledge. On the other hand, in the preparation for concentrated attacks, and for first missions in new zones, a very exact treatment of the operational order was required.

(3) The operational order was first given by the unit CO to the Staffel CO’s, who then left and passed on the information to their pilots at the Staffel dispersal areas around the airfield. Certain points could be omitted and other things important for the Staffel would be added, like time to start engines, sequence for taxiing, composition of the Rotten (two-ship) and Schwärme (four-ship) Flights.

(4) The speed as well as the exactness of the dissemenation of the order was decisive. Since the Staffel CO’s were already at the operations room when the order arrived and could be informed at once, the time required to prepare for take-off was not usually more than 15–25 minutes. (Time required to brief the Staffel CO’s, ride of Staffel CO’s from operations room to Staffel dispersal areas, briefing of the readied crews by the Staffel CO’s, marching of pilots to aircraft, starting, and taxiing to take-off).

(1) The mission begins with starting the engines and taxiing to take-off. The principle was not to permit any traffic jams at take-off because massed aircraft at start presents a very good target for enemy air attacks, and moreover, lubrication and cooling of the F.W. 190 engine (BMW 801) were bad at low RPM.

It was therefore necessary to observe even in taxiing the sequence of takeoff and formation laid down in the operational order. As far as possible aircraft taxied in Rotten from the dispersal areas and took-off at once. A special appointed take-off officer had to see that take-offs took place quickly and smoothly.

(2) Assembling Uninterrupted taking-off of one Rotte after another was a prerequisite for quick assembly in the air. The quicker the formation assembled, the less vulnerable it was to enemy air attacks.

The assembly usually took place in a large curve around the airfield. On missions which were to go to the limits of the endurance of the aircraft, they had, however, to set out on course at once, and the leading aircraft throttled back so the rear elements could catch up. This last type of assembly took longer and was only possible when enemy fighter attacks were not to be expected.

The ordered formation is assumed during the assembly.

(3) Flying Formation. In the formation the following basic demands must be satisfied:

(a) The formation leader must be able to oversee his entire formation.

(b) No lagging behind, keep the formation closed up laterally and vertically. The fulfilling of requirement (b) insured at the same time the maneuverability inside the formation, the observations of the entire air space, and protection against enemy fighters. Even if enemy A.A. opened up, the effect of the fire could be escaped by evasive flying.

The formation most frequently used was the Gruppe ‘vic’. Between the individual aircraft the following distances were observed in each Schwarm:

Lateral interval – 5–6 wingspans

Front to rear – ½ aircraft length

Vertical interval – ½ aircraft height

The last Schwarm in every Staffel was stepped up about 150–300 feet and took over for the time being the fighter cover for the Staffel.

The observation jobs in a formation were assigned as follows:

(a) Schwarm leader: Observation of the ground and orientation.

(b) Pilots on each flank of the formation: Look-outs for enemy fighters (must be especially good pilots).

To make easy the assembly and the keeping of formation, the Staffeln were designated by colors (Staff-blue, 1st-white, 2nd-red, 3rd-yellow). These colors were used on the numbering on the fuselage of the aircraft, from 1 to 16. Staffs were indicated with chevrons or dashes before the numbers, and the propeller spinners were painted the same color. The special unit insignia like coats-of-arms and so on which were used early in the war were later forbidden on grounds of security in ground attack units.

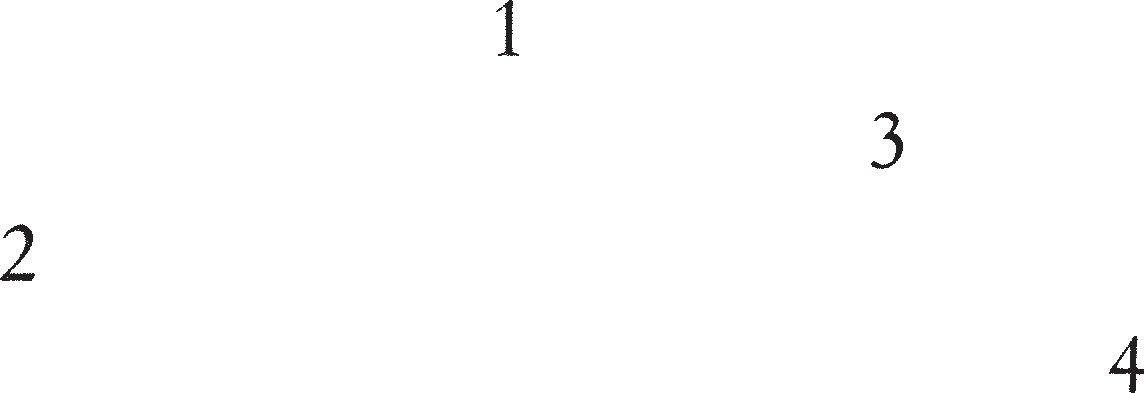

At low levels, the column of Schwarms was sometimes preferred. The following is a detailed breakdown of the average type of formation shown schematically.

Schwarm formation, schematic, for F.W.190 ground attack units. As Viewed From Above.

As Viewed From the Side.

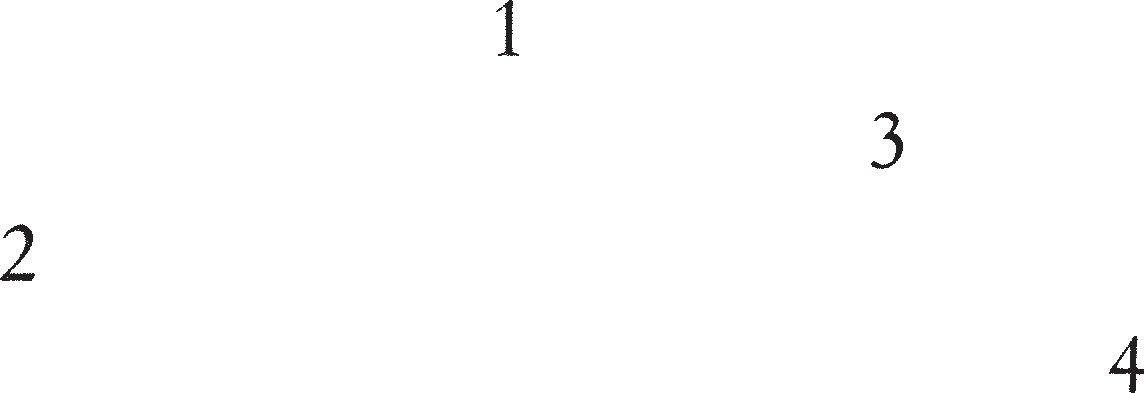

Staffel Formation As Viewed From Above.

1st Schwarm

2nd Schwarm

4th Schwarm

150-300 feet higher

3rd Schwarm

As Viewed From the Side.

3rd Schwarm

2nd Schwarm

1st Schwarm

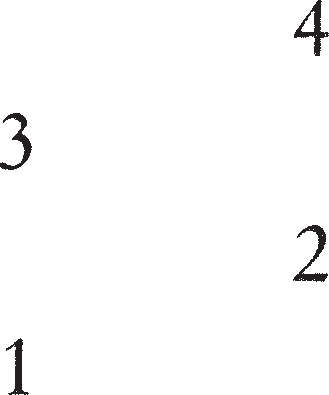

Gruppe ‘Vic’ Formation, Schematic.

As Viewed From Above.

Staff Schwarm

With C.O.

1st Staffel

2nd Staffel

3rd Staffel

600-1200 feet higher

As Viewed From the Side

2nd Staffel

1st Staffel

Staff Schwarm with C.O.

As Viewed From Head On.

3rd Staffel

2nd Staffel

1st Staffel

Staff Schwarm with C.O.

(4) The flight in to the target. Important points are: (a) course; and (b) altitude.

(a) Course: Usually a direct course was flown to the target from the airfield or from the place of rendezvous with the fighter escort. In very obscure country, especially prominent landmarks were flown over. Over already conquered territory infested with partisans the course often led along the safe railroads or roads. When targets were hard to find, points in the vicinity of the target which were easy to see were first approached.

In the determining of the course, the enemy defensive situation, in the air as well as on the ground, had to be taken into consideration. As far as possible enemy fighter airfields, fighter areas, and known A.A. concentration points were detoured. Further, repeated changes of course were used to confuse the enemy observer corps.

All such deviations from the basic course from airfield to target and back to airfield further limited the already small range of German aircraft and thus were not always possible, especially when the target was already just about at the limit of the F.W. 190’s range.

(b) Altitude: As a matter of principle, a high approach flight was favored. By high approach is meant all altitudes above the effective range of light A.A. guns, or about 4,500 feet. For missions in the vicinity of the front, an altitude of about 4,500 to 7,500 feet was adequate, while for deeper penetrations greater altitudes were desirable. In the final analysis the decisive things in determining altitude were the type of attack intended and the strength of enemy air defenses. In areas with strong fighter protection, an altitude of 15,000 feet or a flight just under the ceiling was necessary to prevent surprise by enemy fighters from above.

To insure surprise, flight at tree top levels was sometimes effective. In this way, enemy A.A. was limited in its effectiveness and early detection by enemy radar was prevented.

A very important factor for the determination of the course and altitude as well was the weather. ‘The weather is the terrain of the flyer.’ Skillful use of weather was the duty of every formation leader. Especially liked was medium cloud of 4/10 to 6/10 at altitudes of about 6000 feet. Such weather permitted a relatively well covered flight in, but permitted at the same time a certain orientating by looking at the earth. Closed cloud layers under 3000 feet often forced the aircraft to fly at tree top levels, in order to cancel out ground fire, which was especially effective against aircraft silhouetted against a low ceiling.

(5) Conduct of Attacks. (a) Dive Attacks; (b) Shallow dive attacks; (c) Low level attacks; (d) Leading formations; (e) Radio traffic; (f) Anti-tank raids; and (g) Attacks against shipping.

(a) Dive attacks: Upon approaching the target, the attack formation is assumed. Within the Staffel the attack formation is usually the battle column (Gefechtsreihe). Battle Column:

This formation is purposely vague, to allow plenty of jockeying around to get on the target and to present no regular target to A.A. Each Schwarm leader stays ahead of his Schwarm, but otherwise position goes by the board The Rotten (2s) try to keep contact too.

Within the Gruppe the formation of the Staffeln is arranged according to the type, size, and area of the target.

Where ground A.A. is very strong and targets fixed and easy to recognize, the dive is started directly from the altitude of approach. The direction of the dive was determined by the wind and the form of the target. If possible an attempt was made to utilize the clouds and sun for cover and to so carry out the dive that directly after the dropping of bombs, the pull out and flight away would take place over undefended areas in the direction of home.

It was important that the attack be carried out in the shortest possible time. (With formation well closed up to prevent the A.A. from bringing guns to bear on stragglers).

The formation leader had to have his formation strictly under control. He determined the entire details of the attack, i.e. start of dive, dive angle (80-50°), pulling out, and the get away. Formation leading with the help of radio was not necessary except in special cases.

Attacks on moving or inconspicuous targets were begun from medium altitude. Where the approach altitude was high, the formation sacrificed altitude toward the target and reached the final altitude by curving dives or short repeated dives, to reduce A.A. effectiveness. During this loss of altitude, the formation leader assigned targets by radio.

The dropping altitude was set according to the defense, the type and especially the size of the target, and the necessary radius of the pull-out curve, determined by the speed of the aircraft, resulting from the angle, length, and speed of the dive. Usually the dropping altitude was about 3000 feet.

If the attack was to be carried out in a single dive, the bombs were dropped in salvo or one after the other, according to the nature of the target. The bombing technique is especially laid down in OKL Tactical Instructions, #4 of 13 May 1944.

(b) Shallow Dive Attacks: Shallow dive attacks were carried out when the permissible altitude was no longer sufficient for a dive attack, because of ceiling, visibility of target, or when the target was only weakly protected. The dive began usually from about 3,000–6,000 feet, and the angle lay between 50° and 20°. Attack formation and direction of attack were determined by the same factors as in dive attacks.

The dropping altitude was determined by bomb type and fuse type, and basically bombs were dropped from as low as possible to insure more hits. As far as ground defenses allowed, attacks were repeated several times. In such cases, the bombs were dropped by each aircraft in pairs or singly.

During shallow dive attacks the possibility of simultaneous strafing arose, fire was not opened more than 800 yards from the target. In ground attack missions it proved wise, first to shoot a little below the target, if strikes could be seen on the terrain in question. After successful lateral correction, the aircraft was just nearer enough to the target that the shot then lay on the target.

(c) Low Level Attacks: Low level attacks were carried on in bad weather or where surprise was required. Success with bombs was small against most ground targets on such attacks, since the bombs had to be dropped with some delayed action in order not to endanger the dropping aircraft with fragments or blast. If possible, they pulled up to 900 to 1200 feet just short of the target in order to recognize the target better and more effectively attack it.

A special type of bombing at low level was the so-called turnip bomb run (a type of mast-high bombing). It was used against shipping and by some experts even against tanks.

Since the effect of bombs in low level attacks was usually minor, the main effort in such attacks lay in strafing. Low level attacks made from a low level approach needed especially good preparation, since the locating of targets and proper attacking units was difficult and absolutely had to click.

(d) Leading Formations: As a matter of principle, as far as the ground defenses permitted it, as many attacks as possible were carried through one after another. For this purpose strict control by the formation leader was necessary. He had to get his Staffeln onto the various targets according to their importance and still hold the formation together. It was the rule that the small units, like the Staffeln and Schwärme had to insure their own cohesion.

Since during such missions of long duration the formation was subject to fighter attacks, the formation leader had to use parts of his forces at altitude for fighter cover, in case no additional fighter cover had been provided.

If A.A. defense was anticipated, usually parts of the units were from the beginning entrusted with combatting the A.A. In other cases, the formation leader committed during the attack itself some elements for A.A. attacks. The minimum strength for attacking an A.A. position was a Schwarm, which could attack the position simultaneously from different directions with strafing and small bombs.

For every repeated attack, the correct attack position was resumed. For this purpose a relatively undefended area near the front was sought out, utilizing the great speed gained in the dive for evasive maneuvers. In this area the necessary altitude was regained and the next attack begun.

(e) Radio Traffic: Radio traffic was supposed to be limited to that absolutely necessary. During surprise attacks, radio silence had to prevail until the attack was carried through. R/T conversation took place usually only between the formation leader and the Staffel C.O.s, and, where Staffeln operated alone, between the Staffel C.O. and the Schwarm leaders. Other pilots were only supposed to use R/T in emergencies or to make special observations. The R/T between the formation and the ground attack control stations on the ground was conducted by the formation leader only. Call names were used, except in rare cases, not for security purposes but for purposes of better contact.

(f) Anti-Tank Raids: Anti-tank missions were conducted in the same manner as other ground attack missions, as shallow dive and low level attacks. For the special anti-tank units, cooperation with bomb carrying ground attack units to keep down A.A. defenses was especially important.

The most important type of anti-tank operations were those with large caliber weapons and rockets. With cannon of 3 cm. and 37 mm. the direction of attack was determined by the necessity of scoring hits of 90° angle of impact on the vulnerable parts of the tank, usually the stern. Shooting at heavily armored parts was useless. For RP attacks, these limitations did not apply.

The attack took place in Rotte or Schwarm formation, in battle column, and the interval between aircraft was large enough that the first aircraft attacking was not endangered by the ones behind it and so that mutual interference in aiming did not occur. Until reaching the effective range, 200 to 50 meters, they had to fly evasively in order to minimize the ground defense, which always got stronger and stronger. For attacks with RP the same principles pertained.

A few ground attack pilots have destroyed tanks with the turnip tactics, by approaching the target almost on the ground and released the bomb right next to the tank, so that it flew into the suspension and completely destroyed the tank.

(g) Shipping Targets: Against shipping targets the dive attack was most used. This was because of the defense fire, especially with warships and convoys. A freighter was attacked with at least a Schwarm, warships and destroyers with at least a Staffel. Attacks were made from various directions, to divide up the defensive fire. Large ships sailing alone could well be attacked with the turnip procedure. Light craft like motor torpedo boats could be attacked in shallow dives and strafed. Light landing craft were repeatedly attacked and destroyed on the Eastern Front by anti-tank aircraft using 3 cm. cannon and HE ammunition.

(6) Reassembly and the Flight Back. At the end of the ground attack operation it was important to reassemble the formation as quickly as possible. By radio or by signal (like waggling the wings) the formation leader gave the order for reassembly. In so doing he flew with the first elements, all throttled back, and continually curving to make a quick reassembly easier for the rest of the formation. This type of assembly always took place in areas where defense was weak.

The flight back took place in the same formation as the flight in. As often as possible, the altitude was not less than 3,000 feet and the route avoided defended spots just as on the approach. Over friendly territory, the formation flew back along roads used by our troops. They kept a little away from the roads themselves, so that friendly troops could see them but would not become too disturbed.

(7) Landing. The landing took place by Staffeln. The Staffeln landed in a column as quickly as possible. The Staffeln remained in flight formation over the field until their turn came to land.

(8) Success Report. For operations of ground attack units in support of the army, a detailed success report for the mission was very important. The sooner this report got to headquarters the quicker it could be utilized. Therefore after landing the various pilots assembled around their Staffel CO. The CO’s took down the reports about the victories, observation reports, and serviceability of the aircraft. Immediately afterward, each went to the Gruppe CO. The latter had already reported to headquarters by telephone any special events which had occurred. On the basis of the reports of the Staffel CO’s the detailed success report was now relayed on to the headquarters. It contained: victories scored, losses, conclusions about the enemy situation, front lines, ground defense, fighter defense, and other special remarks. Finally the new probable time of next readiness was reported, together with the number of serviceable aircraft.