Author

The authorship of 1-2 Samuel is unknown. Jewish tradition, at least as far back as the Babylonian Talmud of the sixth century AD, believed the prophet Samuel to be the author. A major problem is that 1 Sam 25:1 and 28:3 record Samuel’s death, and he obviously could not have written the material after his death. Some commentators argue that Samuel wrote much of the document up to that point and other prophets then took over the writing. They cite 1 Chr 29:29 as evidence: “As for the events of King David’s reign, from beginning to end, they are written in the records of Samuel the seer, the records of Nathan the prophet and the records of Gad the seer.”

The title “Samuel” refers to the prophet Samuel as the pivotal figure in the books of 1-2 Samuel. As Israel’s final judge, Samuel is the transitional figure from a tribal confederacy in the period of the judges to a united monarchy; Samuel anointed Saul and then David as the first kings of Israel (1 Sam 10:1; 16:13). Samuel and his name, however, appear nowhere in 2 Samuel. The reason that 2 Samuel bears his name is because originally 1-2 Samuel were one book. The Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT, is probably the first to divide “Samuel” into two separate books because of its length.

Date

First Samuel begins with the birth and call of the prophet Samuel, which occurred in the eleventh century BC. 2 Samuel ends near the close of David’s reign (ca. 1010–970 BC). However, the final form of 1-2 Samuel does not date from the time in which the events recorded took place. Some of the material does originate from the date of the event, such as David’s eulogies for Saul and Jonathan (2 Sam 1:17–27) and his lament for Abner (2 Sam 3:33–34). Thus, the final composition relies on annals, poems, and stories that come from an earlier period.

The text itself provides adequate proof that the final composition of the books is later than the events recorded. First, the words “to this day” or similar expressions indicate that the author is narrating events that had occurred prior to his time (1 Sam 5:5; 6:18; 27:6; 30:25; 2 Sam 4:3; 6:8; 18:18). Second, 1 Sam 27:6 states, “So on that day Achish gave him Ziklag, and it has belonged to the kings of Judah ever since.” This statement reflects both a situation in which a number of kings have ruled over Judah since the death of Solomon and the division of the united monarchy into two kingdoms. Third, 2 Sam 5:5 summarizes the length of David’s reign: “In Hebron he reigned over Judah seven years and six months, and in Jerusalem he reigned over all Israel and Judah thirty-three years.” At the close of 2 Samuel, however, David’s reign is not yet completed. Fourth, the author explains customs of the early monarchic period because they are no longer used during his time (1 Sam 9:9; 2 Sam 13:18).

All evidence suggests that the final editing of the two books occurred after some of “the kings of Judah” reigned (1 Sam 27:6), that is, in the ninth–eighth centuries BC. It is certainly reasonable to believe that an official historian wrote 1-2 Samuel within one to two centuries of the events. There is no compelling reason to think that the two books were given a final form in the exilic or postexilic periods.

Purpose

The primary purpose of 1-2 Samuel is to record the establishment of the kingship in Israel. This event is a pivotal moment in the unfolding of God’s revelational history.

The kingship is, in the first place, an initial fulfillment of ancient prophecy. God revealed to the patriarchs that kings would descend from them (Gen 17:6, 16; 35:11). The great promise that Jacob gives to his son Judah and his descendants is that the scepter, the symbol of kingly rule, will not depart from the tribe of Judah. The kingship will reach its climax in a supreme ruler who will one day come from Judah (Gen 49:10). Instituting a monarchy in Israel is clearly consistent with God’s plan and will for his people. The type of kingship that Israel is to have is a theocratic monarchy, in which Israel has a human king who obeys the Lord, the ultimate, sovereign king (Deut 17:14–20).

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with the elders requesting a king in 1 Sam 8. The problem is their desire for a king like the other nations have rather than for one who is part of a theocratic monarchy submitted to the Lord. By desiring an autonomous human king, the elders reject God as king (1 Sam 8:7). Samuel warns Israel that a king like those in the ancient Near Eastern nations around them will be oppressive, demanding, and self-centered (1 Sam 8:11–18). Saul, the first king of Israel, turns out to be the type of king that Samuel had warned against.

David’s kingship initially fulfills what God promised his people. David is from Judah and is a man after God’s own heart (1 Sam 13:14). God inaugurates and establishes David’s dynasty in Israel, not Saul’s (1 Sam 13:13–14; 15:28). Although David is a complicated figure and is sinful, he recognizes that God is the ultimate king in Israel (Pss 10:16; 24:8–10; 29:10).

David’s kingship also points forward to the final Messianic king (Pss 2; 72; 110). The Lord promises David that his offspring would sit on the throne of Israel “forever” and that his son will build a temple for the Lord (2 Sam 7:12–16). This is a double prophecy: Solomon fulfills the first stage, and the Messianic king, “the son of David” (Matt 1:1) who builds a new temple (John 2:19–22), fulfills the second.

Style and Content

Like many books in the Bible, 1-2 Samuel contain a variety of literary genres. The primary genre is narrative, but non-narrative material often interrupts it: poetry (1 Sam 15:22–23), prophecy (2 Sam 7:4–17), prayer (1 Sam 2:1–10), lament (2 Sam 1:17–27; 3:33–34), chant (1 Sam 18:7; 21:11; 29:5), military catalog (2 Sam 8:1–14), lists of court officials (2 Sam 8:15–18; 20:23–26), parable (2 Sam 12:1–4), psalm/song (2 Sam 22:1–51), military lists (2 Sam 23:8–39).

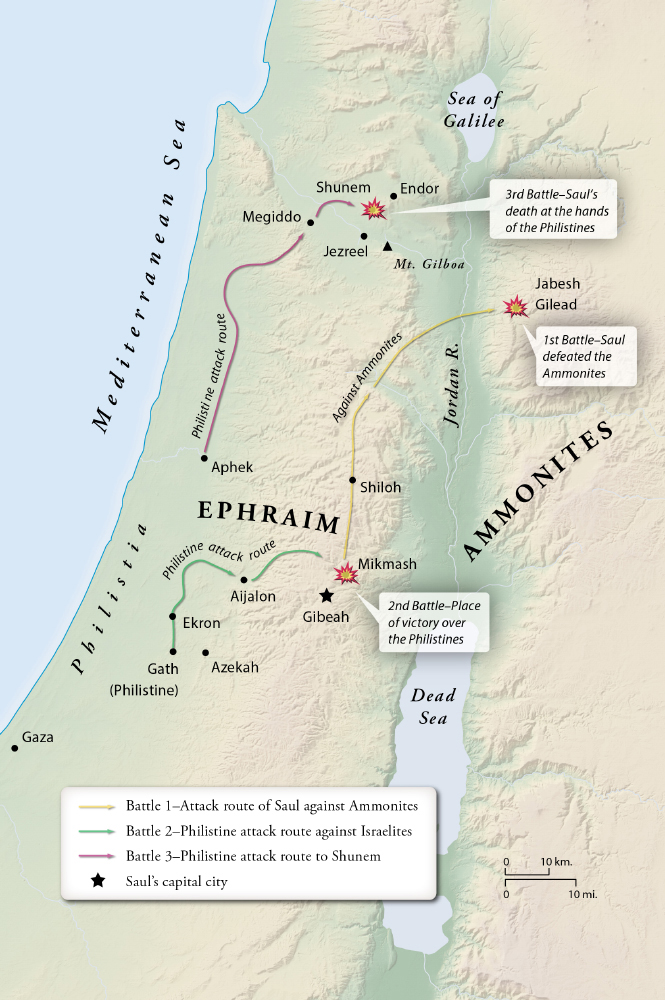

The biblical writer does not provide a broad survey of the history of Israel during the judges and the early monarchic period but focuses on the three most prominent leaders of the day: Samuel, Saul, and David. 1 Sam 1–8 describes Samuel’s birth, call, and judgeship. As the last judge of Israel, he transitions Israel from the period of the judges to the monarchic period of the kings of Israel. 1 Sam 9–31 concentrates on the failed rule of Saul, the first king of Israel. It narrates his call and anointing to the office of king, his good beginning as king, God’s rejection of him because of his disobedience, the rise of David, and Saul’s death at the hands of the Philistines on Mount Gilboa.

2 Samuel is a history of David’s kingship. The first part (chs. 1–9) describes how David rises to the position of ruler over all Israel (2 Sam 2:1—5:5), consolidates power (2 Sam 5:6—7:29), and conquers the nations surrounding Israel (ch. 8). It sounds a high note: “The LORD gave David victory wherever he went” (2 Sam 8:14). The second major section narrates David’s complacency and sin (chs. 10–12). The book’s pivot is David’s adultery with Bathsheba (2 Sam 11:1—12:25). The third major section of 2 Samuel almost exclusively describes how David deals with rebellion in his own kingdom (chs. 13–20).

The author deliberately contrasts the kingships of Saul and David. Their lives generally run parallel: they both start off well with strong military successes, and they win the favor of the people under their rule. However, their ascendancies are followed by grievous sins as they both disobey God’s word. The similarity ends with how the two of them deal with their sin. Saul’s sin leads to bitterness, vengeance, and hatred directed toward David and others, but David shows genuine sorrow and contrition for his sin (Ps 51). The Lord forgives David, although that does not remove his sin’s severe temporal consequences. The Lord establishes David’s dynasty, but not Saul’s. It is through David’s line that the Messianic king will appear: Saul, thus, serves as a foil to David in the plot of 1-2 Samuel.

Particular Challenges

Text

The Hebrew Masoretic Text of 1-2 Samuel is loaded with difficulties, and it has suffered numerous scribal errors in written transmission from one generation to another. Perhaps the most difficult verse in regard to the text in all the OT appears in 1 Sam 13:1. The intensity of the degree of perplexity is reflected in the wide variety of English translations of the verse:

• “Saul was thirty years old when he became king, and he reigned over Israel forty-two years” (NIV).

• “Saul lived for one year and then became king, and when he had reigned for two years over Israel . . .” (ESV).

• “Saul reigned one year; and when he had reigned two years over Israel . . .” (KJV).

• “Saul was fifty years old when he became king, and he reigned over Israel for twenty-two years” (NEB).

• “Saul was thirty years old when he began to reign, and he reigned forty two years over Israel” (NASB, 1995).

• “Saul was thirty years old when he became king, and he reigned over Israel for twenty-two years” (REB).

The Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT, simply omits the verse altogether. While no other verse in 1-2 Samuel is as textually difficult as 1 Sam 13:1, there are many others that are considerably hard to understand and interpret.

The Septuagint is notorious for its differences with the Masoretic Text of 1-2 Samuel. Many scholars assume that the Masoretic Text has been deeply corrupted through scribal errors in written transmission and that the Septuagint actually better reflects the original Hebrew text. Numerous scholarly attempts have been made to correct the corrupted Masoretic Text texts on the basis of the Septuagint. So for example, in the Masoretic Text, the story of David and Goliath contains 88 verses, and the Septuagint lacks 39 of those verses. Many commentators assume that the Septuagint preserves the earlier text and that the Masoretic Text adds a parallel account to it to make up the final story. The issue of which text reflects the earliest manuscript is actually quite complicated. The degree of difficulty is reflected in the following points:

1. The Dead Sea Scrolls of Samuel (second century BC to first century AD) support only some of the Septuagint readings, certainly not most of them.

2. The existing Septuagint manuscripts often differ among themselves in written transmission.

3. Parts of the Masoretic Text do reflect the earliest Hebrew texts. For example, the Septuagint of 1 Sam 1–2 appears to intentionally rewrite the earlier text preserved in the Masoretic Text.

4. The Septuagint at times makes deliberate literary changes to some verses by adding material to them (e.g., 1 Sam 5:3).

When all is said and done, one needs to be cautious and careful in regard to the textual problems of the Masoretic Text of 1-2 Samuel. The problems are not easily solved. However, for the most part, the Masoretic Text stands on fairly solid ground. The NIV translation follows it closely, although it occasionally agrees with the Septuagint (e.g., 1 Sam 8:16; 13:5, 20; 14:41).

Parallel Passages

Another specific area of controversy regarding the interpretation of 1-2 Samuel is the appearance of numerous parallel passages elsewhere in Scripture. 1 Samuel has only a few parallels, but 2 Samuel has many in the book of 1 Chronicles. The parallels between the latter are extensive but often with many additions and subtractions. It has been widely accepted for a long time that the author of Chronicles uses Samuel as a major source in his writing. But his interpretation of history is different in that he emphasizes different things because of his peculiar historical and theological context. The Chronicler writes much later than the author of Samuel, and his audience is the people who have returned from exile in Babylon. The people return in order to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem, to worship, and to create a sense of national identity. The Chronicler encourages them in these tasks by recounting in detail the work of David and Solomon in regard to the sanctuary. He does not retell the stories of David’s battles with Saul or his sin with Bathsheba. Such events do not fit into the Chronicler’s purpose.

David’s song in 2 Sam 22 is almost identical to Ps 18. There are minor variations between the two accounts; several involve the addition of a conjunction in the Hebrew in the psalm (vv. 13, 15, 17, 27, 42). Some differences are larger. For instance, in Ps 18, v. 1 adds the line “I love you, LORD, my strength” (when compared to 2 Sam 22:1), and v. 2 subtracts the line “my refuge and my savior—from violent people you save me” (when compared to 2 Sam 22:2–3). The title, or superscription, of Ps 18 fills out 2 Sam 22:1, and a musical notation is added that says, “For the director of music.” That addition helps to highlight the fact that only this song, along with its superscription, appears in toto in two different places in the Bible. In 2 Sam 22, the song is an individual hymn of praise by King David; its appearance in the book of Psalms is as a public hymn for singing in the temple.

Themes and Theology

Four of the key themes of 1-2 Samuel are kingship, kingdom, God’s sovereignty over the world and, in particular, the affairs of humanity, and God’s redemptive covenant.

1. Kingship. The institution of kingship is at the very heart of 1-2 Samuel. Appearing over 350 times, “king” is the leading word in 1-2 Samuel. In addition, the subject matter of 1-2 Samuel centers on the major leaders (e.g., Samuel), kings (Saul and David), and men who want to be king in Israel (e.g., Absalom). In other words, the books do not concentrate on the everyday lives of the common Israelite but picture the upper echelon of Israelite society, principally the leaders in the palace courts and the military.

The foundational pillar of the Hebrew conception of kingship is that God is King and that he always has been and always will be King. As the psalmist so forcefully declares, “The LORD is King for ever and ever” (Ps 10:16) and “the LORD is enthroned as King forever” (Ps 29:10). Before Israel captured the land of promise, God had declared to the people that they would have a king (Deut 17:14–20). This human king would be subject to God as king and fully dependent on God’s word as the rule of the kingdom. The ultimate king of Israel is the Lord, and the human ruler is to serve as his deputy. When Israel chooses a ruler in 1 Sam 8, the elders reject this plan by choosing a king like all the surrounding nations. This king is autonomous. The Lord himself assesses that choice by saying, “They have rejected me as their king” (v. 7).

The prophet Samuel warns the people that they are seeking a king who will be self-centered and selfish (vv. 10–18). But they do not heed his warning; they demand a king like all the nations. And that is exactly what Israel gets with their first king, Saul. While God chooses Saul as the first king of Israel, Saul is corrupted by power and does not submit his kingship to the Lord. The biblical writer describes the demise of Saul and the rise of David in contrasting terms. David is a man after God’s own heart, and he founds a dynasty that will last forever (2 Sam 7:16).

Although David is perhaps the greatest king to sit on the throne of Israel, his rule is deeply flawed and broken. By the second half of 2 Samuel, David’s kingdom is in disarray. The rebellions of Absalom and Sheba have taken their toll, and David sins greatly by taking a census of his military. Although David is the prototype for the Messianic King, he is not the Messianic King. At the close of 2 Samuel, the reader is left yearning for the coming of the king who truly keeps the word of God (Deut 17:14–20). That figure arrives in the person of Jesus Christ, the Messianic King, who is the “Son of David” (Matt 12:23) and comes “from David’s descendants and from Bethlehem, the town where David lived” (John 7:42).

2. Kingdom. One of the great promises that God gives to Israel at Mount Sinai is that they will become a kingdom under the rule of God. The Lord says to the people through Moses, “Although the whole earth is mine, you will be for me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exod 19:5b–6a). A kingdom is a territory with human subjects under the governmental rule or control of a monarch. After Sinai, God leads the people to the land of promise, and they conquer and secure that territory under the leadership of Joshua. A primary purpose of 1-2 Samuel is to establish that territory under the authority and power of a king. Some commentators call this period the kingdomization of Israel. Saul’s words to David in 1 Sam 24:20 reflect that: “I know that you will surely be king and that the kingdom of Israel will be established in your hands.”

The kingdom of Israel, however, is never completely united under one king. Hostility between the northern tribes and southern tribes is ever present (2 Sam 2:10; 19:43; 20:1–2). This animosity eventually leads to the division of Israel into two kingdoms (1 Kgs 12:16–17), and invading foreign armies finally destroy both kingdoms.

Does this sad conclusion nullify God’s promise that his people would be kingdomized? Certainly not. When the Messianic King, the son of David, came to the earth, he proclaimed “the good news of the kingdom” (Matt 4:23; 9:35). Jesus is the final and ultimate king (Matt 2:2; 21:5; 27:37, 42). And in his coming to the earth, he inaugurates the final and ultimate kingdom. As Peter says to the people of God, “You are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s special possession” (1 Pet 2:9). This kingdom reaches its zenith in the new heavens and the new earth, which is “an inheritance that can never perish, spoil or fade. This inheritance is kept in heaven for you” (1 Pet 1:4).

3. The sovereignty of God. The doctrine of the sovereignty of God teaches that everything that occurs in heaven or on earth, from the greatest to the least, unfolds according to the purpose and plan of God. In other words, God has ordained whatever happens. There are simply no surprises for him because he established the plan from all eternity (Matt 25:34; Eph 1:4). Hannah’s prayer offers a glimpse into the sovereignty of God with four merisms (a merism is a figure of two opposites that are all-inclusive):

[1] The LORD brings death and makes alive;

[2] he brings down to the grave and raises up.

[3] The LORD sends poverty and wealth;

[4] he humbles and he exalts.

He raises the poor from the dust

and lifts the needy from the ash heap . . .

For the foundations of the earth are the LORD’s;

on them he has set the world. (1 Sam 2:6–7)

Although at times it may appear that God changes his mind or his plan, “He who is the Glory of Israel does not lie or change his mind; for he is not a human being, that he should change his mind” (1 Sam 15:29). Indeed, his sovereign will and plan are unshakable: “the plans of the LORD stand firm forever, the purposes of his heart through all generations” (Ps 33:11).

The books of 1-2 Samuel clearly reveal God’s sovereignty in the seemingly minor events of everyday life. God orchestrates the ordinary, sometimes mundane, events in the books. For example, Kish tells his son Saul to go search for the family’s lost donkeys (1 Sam 9). This ordinary circumstance leads to Saul’s meeting with Samuel at Ramah and being anointed as king. God tells Samuel “the day before Saul came” what is about to happen (v. 15). The meeting is not a chance happening but unfolds according to God’s will and word. Major events, such as the choosing of David as Saul’s replacement, are also by God’s predetermined plan (1 Sam 16:7).

4. God’s redemptive covenant. The books of 1-2 Samuel fit into the larger picture of the unfolding of God’s redemptive-historical plan. So for instance, the Lord’s specific intervention to cause Hannah to give birth to Samuel (1 Sam 1:19–20) and her subsequent song of praise (1 Sam 2:1–10) are paradigms of the miraculous birth of Jesus and Mary’s Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55). In addition, God’s choosing David to be king and David’s line to sit on the throne of Israel forever climaxes in the appearance of the Messianic King, who is the eternal ruler. Thus, God says to David through Nathan the prophet, “Your house and your kingdom will endure forever before me; your throne will be established forever” (2 Sam 7:16). This promise that God will establish David’s house eternally is fully established only in the coming of Christ.

Outline

I. Birth, Youth, and Call of the Prophet Samuel (1 Sam 1:1—4:1a)

A. The Birth of Samuel (1:1–20)

B. Hannah Dedicates Samuel (1:21–28)

C. Hannah’s Prayer (2:1–11)

D. Eli’s Wicked Sons (2:12–26)

E. Prophecy Against the House of Eli (2:27–36)

F. The Lord Calls Samuel (3:1—4:1a)

II. The Ark Narrative (4:1b—7:2a)

A. The Philistines Capture the Ark (4:1b–11)

B. Death of Eli (4:12–18)

C. The Birth of Ichabod (4:19–22)

D. The Ark in Ashdod and Ekron (5:1–12)

E. The Ark Returned to Israel (6:1—7:2a)

III. Samuel Subdues the Philistines at Mizpah (7:2b–17)

IV. Israel Asks for a King (8:1–22)

V. Choosing and Anointing a King (9:1—10:27)

VI. Saul Rescues the City of Jabesh (11:1–11)

VII. Saul Confirmed as King (11:12–15)

VIII. Samuel’s Farewell Speech (12:1–25)

A. Samuel’s Plea of Innocence (12:1–5)

B. Samuel’s Lawsuit Against the People (12:6–19)

C. A Final Warning (12:20–25)

IX. Saul’s Kingship (13:1—15:35)

A. Samuel Rebukes Saul (13:1–15)

B. Israel Without Weapons (13:16–22)

C. War Against the Philistines (13:23—14:46)

1. Jonathan Attacks the Philistines (13:23—14:14)

2. Israel Routs the Philistines (14:15–23)

3. Jonathan Eats Honey (14:24–46)

D. Summary of Saul’s Kingship (14:47–52)

E. The Lord Rejects Saul as King (15:1–35)

X. Saul’s Fall and David’s Rise (16:1—31:13)

A. Samuel Anoints David (16:1–13)

B. David in Saul’s Service (16:14–23)

C. David and Goliath (17:1–58)

1. The Setting of War (17:1–11)

2. David at Home (17:12–19)

3. David in the Ranks of Israel (17:20–30)

4. David Volunteers (17:31–39)

5. The Fight (17:40–54)

6. David’s Pedigree Revealed to Saul (17:55–58)

D. Saul’s Growing Fear of David (18:1–30)

E. Saul Tries to Kill David (19:1–24)

F. David and Jonathan (20:1–42)

G. David at Nob (21:1–9)

H. David at Gath (21:10–15)

I. David at Adullam and Mizpah (22:1–5)

J. Saul Kills the Priests of Nob (22:6–23)

K. David Delivers Keilah (23:1–6)

L. Saul Pursues David (23:7–29)

M. David Spares Saul’s Life (24:1–22)

N. David, Nabal, and Abigail (25:1–44)

O. David Again Spares Saul’s Life (26:1–25)

P. David Among the Philistines (27:1—28:2)

Q. Saul and the Medium at Endor (28:3–25)

R. Achish Sends David Back to Ziklag (29:1–11)

S. David Destroys the Amalekites (30:1–31)

T. Saul Takes His Own Life (31:1–13)

XI. David’s Early Success (2 Sam 1:1—10:19)

A. David Hears of Saul’s Death (1:1–16)

B. David’s Lament for Saul and Jonathan (1:17–27)

C. David Anointed King Over Judah (2:1–7)

D. War Between the Houses of David and Saul (2:8—3:5)

E. Abner Goes Over to David (3:6–21)

F. Joab Murders Abner (3:22–39)

G. Ish-Bosheth Murdered (4:1–12)

H. David Becomes King Over Israel (5:1–5)

I. David Conquers Jerusalem (5:6–16)

J. David Defeats the Philistines (5:17–25)

K. The Ark Brought to Jerusalem (6:1–23)

L. God’s Promise to David (7:1–17)

M. David’s Prayer (7:18–29)

N. David’s Victories (8:1–14)

O. David’s Officials (8:15–18)

P. David and Mephibosheth (9:1–13)

Q. David Defeats the Ammonites (10:1–19)

XII. David’s Grievous Sins (11:1—12:31)

A. David and Bathsheba (11:1–27)

B. Nathan Rebukes David (12:1–31)

XIII. Later Years of David’s Rule (13:1—24:25)

A. Amnon and Tamar (13:1–22)

B. Absalom Kills Amnon (13:23–39)

C. Absalom Returns to Jerusalem (14:1–33)

D. Absalom’s Conspiracy (15:1–12)

E. David Flees (15:13–37)

F. David and Ziba (16:1–4)

G. Shimei Curses David (16:5–14)

H. The Advice of Ahithophel and Hushai (16:15–23)

I. Hushai’s Advice Is Accepted (17:1–23)

J. Absalom’s Death (17:24—18:18)

K. David Mourns (18:19—19:8)

L. David Returns to Jerusalem (19:9–43)

M. Sheba Rebels Against David (20:1–22)

N. David’s Officials (20:23–26)

O. The Gibeonites Avenged (21:1–14)

P. Wars Against the Philistines (21:15–22)

Q. David’s Song of Praise (22:1–51)

R. David’s Last Words (23:1–7)

S. David’s Mighty Warriors (23:8–39)

T. David Enrolls the Fighting Men (24:1–17)

U. David Builds an Altar (24:18–25)

![]()

![]()

![]()