The story of Esther and Mordecai is a literary masterpiece with profound theology: God fulfills his redemptive promises not only through great miracles but also through divine providence working through ordinary events. Even the actions of people who do not worship him are woven into patterns and purposes determined by the sovereign Lord alone.

Author

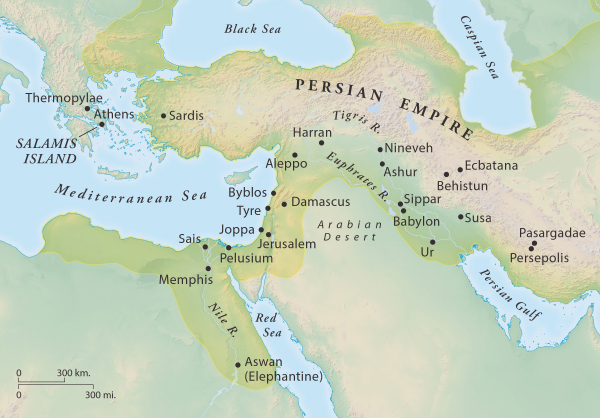

The book of Esther makes no claim about its author, although it likely originated with a Jewish author who lived outside of the Holy Land and was familiar with Susa and the Persian palace.

Date

The story is set in Susa (modern Iran) in the court of the Persian king Xerxes I (Ahasuerus), who ruled 486–465 BC and is remembered by ancient historians as a ruthless and powerful king. But the author writes from a perspective looking back on that time. The events occur after the decree of Cyrus (539 BC) allowed the Jews to return to their homeland, but Esther and Mordecai had remained in exile. It may have been written after 424 BC if the description of Xerxes in 1:1 as the one “who ruled over 127 provinces” was intended to distinguish him from Xerxes II, his grandson who ruled only 45 days in that year. Because the author’s knowledge of Susa and the palace is consistent with archaeological evidence, and because there are many Persian loanwords in the text but few, if any, Greek words, it was probably written within 100 years of the events it records and probably before Alexander’s conquest of Persia in 333 BC. It is written in Hebrew similar to that of 1 and 2 Chronicles, which are also dated to the period of 539–323 BC.

Place of Composition and Destination

The story of the Jews during the reign of Xerxes explains the origin of the festival of Purim for Jews living throughout the Persian Empire. Although the first record of the events was likely written in the region of Susa, the final biblical form may have been written in another location and intended for all who celebrated Purim everywhere.

Particular Challenges

The book of Esther is well known for not mentioning God, miracles, the law, the temple, or the covenant. A further challenge is the moral ambiguity of Esther and Mordecai in comparison to Daniel and his friends, who suffered similar circumstances. The story has also been implicated for inciting violence throughout Jewish history.

Five issues challenge the book’s historical reliability:

1. The names of Vashti and Esther do not agree with the Greek historian Herodotus, who says that Xerxes’ wife was Amestris. But perhaps only Amestris is mentioned because she was the royal wife who gave birth to Xerxes’ successor, Artaxerxes. Or perhaps the name Vashti is meant to be a literary device intended to characterize the queen, for it may have sounded similar to the Old Persian word for “beautiful woman.”

2. The statement in 2:6 suggests that Mordecai would have been over 100 years old. The statement, however, may mean either that Mordecai’s great-grandfather Kish was the one taken into exile or that when Judah went into exile, all of God’s people went into exile, even those who would be born later in Babylon.

3. The enumeration of 127 provinces in 1:1 does not agree with the much smaller number found in other historical sources. But the term translated “province” probably refers to a smaller metropolitan region that encompassed a city (cf. Ezra 2:1; Neh 7:6; Dan 2:49) and suggests that the Jews would have nowhere to hide from the decree of death against them.

4. Persian kings could add to their harem indiscriminately, but they usually married women from only seven noble families, making Xerxes’ marriage to Esther very unlikely. But the ancient writer Plutarch mentions that other Persian kings did sometimes marry outside of the traditional families.

5. The practice of irrevocable decrees is unknown in any other sources from this period.

Rather than deciding whether the book of Esther is history or literature, the real question is how to understand it as both. It would be a shame to be so distracted by apparent historical “problems” that we miss what God is saying in this wonderful story.

Occasion and Purpose

The book was written to document the time when the Jews got relief from their enemies and when their sorrow was turned to joy, the occasion commemorated by the festival of Purim. It not only explains the origin of Purim but also shows how even in exile God’s providential sovereignty over history fulfilled the ancient promise given at the time of the exodus to protect his covenant people (Exod 17:16).

Genre and Structure

The story of Esther is told with irony, satire, and humor, and because of its place in the biblical canon, it is therefore theology told with irony, satire, and humor. Like a parable, it makes its point as a whole unit. The story follows the contours of all good narrative, with the plotline rising as narrative tension is created, peaking, and then coming to closure at the end of the story. But another literary device is also in play in the story—an ancient device that Aristotle referred to as peripety: a sudden turn of events that reverses the expected outcome of a story. The story of Esther is not simply resolved; it is resolved with a series of reversals.

This literary structure is organized around three pairs of banquets that mark the beginning, climax, and conclusion of the story (the first pair in 1:2–8; the second pair in 5:1–8 and 7:1–10; the third pair in 9:17–19), and which reinforce the theological message of the story. This motif of banqueting is especially appropriate in a story that explains the origin of the festival of Purim. The recurring banquet motif focuses the literary structure on the surprising and seemingly insignificant event of 6:1, from which the reversal of fortune proceeds.

The point at which the reversals begin is between Esther’s first banquet for the king and Haman and the second, when the king has a sleepless night. The narrative tension of the conflict between the Jews and Persia and their enemy, Haman, could have been resolved simply by the failure of Haman’s plan and preservation of the status quo. Instead, there is a series of reversals that concludes with a great reversal of fortune for God’s people (cf. 3:10 and 8:2; 3:12 and 8:9; 3:12 and 8:10; 3:13 and 8:11; 3:14 and 8:13; 3:15 and 8:14; 3:15 and 8:15; 4:1 and 8:15; 4:1 and 6:11; 5:14 and 6:13). The use of peripety in Esther is an example of how form and content mutually interact not only to produce an aesthetically pleasing story but to provide the framework in which the theological implications of the story can be understood. This literary structure of reversals found in the book of Esther and its pivot point in an ordinary and insignificant event mirrors on a small scale the structure of all redemptive history. We should expect nothing but death, but we have seen the ultimate peripety, the ultimate reversal of expected ends, in the death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ.

Themes and Theology

It may seem inappropriate to refer to the theology of a book that doesn’t mention God at all, but the explicit absence of God is part of the genius of the book, making a major theological point that God’s redemptive promises are fulfilled through his providence. The great paradox presented by the story is that God is all-powerfully present even where he is most conspicuously absent. The story explores the intriguing interplay between God’s providence and human decisions and actions (1:10–12; 2:17, 21–23; 4:14; 6:1–3). Esther and Mordecai may have been upright people who lived faithfully in exile, but the author presents their actions as morally ambiguous, and they are never evaluated by the narrator. For instance, Esther does not protest life in the king’s harem, as Daniel protested life in the Babylonian court. Mordecai may have had righteous motives for refusing to bow to his superior Haman, but the narrator doesn’t mention that. Despite the narrative ambiguity of their behavior, which is part of the genius of the story, God nevertheless works to fulfill his redemptive promises.

At the time Esther was written, the problem of the destruction of Jerusalem and the exile of God’s people was a theological issue complicated by the problem of the return of some to rebuild Jerusalem. God’s people were asking, “Are we still in covenant with the Lord? What about Jews who chose to remain outside the promised land?” The book of Esther affirms that God is still faithful to the covenant promises he made at Sinai and that those living beyond the borders of the promised land are not beyond the reach of his redemptive protection. This stage in progressive revelation anticipates the Great Commission (Matt 28:18–20), when the whole world would be within the gospel’s embrace. The story presents a great deliverance from the threat of destruction in yet another episode of the ancient war between Israel and its many enemies, such as the Amalekites, the first nation that tried to destroy Israel in its infancy (Exod 17:8–16; Deut 25:17–19). The story also invites reflection on life issues such as the self-deceptive and destructive nature of pride (e.g., 6:4–14), the significance of identifying with God’s people at life’s defining moments (4:12–16), and male and female partnership in God’s plan (9:29–32).

Being in the Christian canon of Scripture, the book of Esther is an example of the reversal of human destiny that ultimately, in the sweep of redemptive history, was accomplished by Jesus Christ. Because of our sin, we should expect nothing but death. But in the ultimate reversal of eternal destiny, because of the cross of Jesus, we have been given life.

Canonicity

The theological message of Esther can be understood only within the larger context of the biblical canon. The canonization of Esther is closely tied to the canonization of the Writings, the third section of the Hebrew Bible in which it is found, which may have occurred as early as the second century BC. Because God and significant elements of Judaism are not mentioned in the book, its value as a canonical book has been questioned in both Jewish and Christian tradition. Despite that questioning, rabbis of the first century said that the book “made the hands unclean,” a reference to its nature as authoritative Scripture. In the early centuries of the Christian church, Esther was accepted almost everywhere in the Western canon, and it attained universal canonical status by the end of the fourth century. Martin Luther famously denounced the book, wishing it were not in the Bible, but its status as a canonical text within both Judaism and Christianity remains secure.

Outline

I. The Jews of Persia Are Threatened (1:1—5:14)

A. Queen Vashti Deposed (1:1–22)

1. Xerxes Is a Powerful and Dangerous King (1:1–8)

2. Queen Vashti Defies Xerxes (1:9–12)

3. The King and Nobles React to Vashti’s Disobedience (1:13–22)

B. Esther, Mordecai, and Haman (2:1—3:15)

1. Esther Made Queen (2:1–18)

2. Mordecai Uncovers a Conspiracy (2:19–23)

3. Haman’s Plot to Destroy the Jews (3:1–15)

C. Mordecai Persuades Esther to Help (4:1–17)

1. Mordecai Mourns Over Haman’s Decree (4:1–5)

2. Mordecai Begs Esther to Intercede (4:6–14)

3. Esther Calls a Three-Day Fast (4:15–17)

D. Esther’s Request to the King (5:1–14)

1. Esther Appears Uninvited Before the King (5:1–5a)

2. Esther Prepares a Banquet for the King and Haman (5:5b–8)

3. Haman’s Rage Against Mordecai (5:9–14)

II. The Reversal of Outcome (6:1—9:19)

A. Mordecai Honored (6:1–14)

1. The King Has a Sleepless Night (6:1–3)

2. Haman Seeks the King’s Permission to Kill Mordecai Immediately (6:4–9)

3. Mordecai Is Honored Instead (6:10–14)

B. Haman Impaled (7:1–10)

1. Esther Prepares a Second Banquet for the King and Haman (7:1–2)

2. Esther Reveals Her Jewish Identity and Accuses Haman (7:3–7)

3. The King Orders Haman Executed (7:8–10)

C. The King’s Edict in Behalf of the Jews (8:1–14)

1. Esther Introduces Mordecai to the King (8:1)

2. Mordecai Receives the Signet Ring Previously Worn by Haman (8:2)

3. Esther Gives Haman’s Property to Mordecai (8:3–8)

4. Mordecai Writes the Counteredict (8:9–14)

D. The Triumph of the Jews (8:15—9:19)

1. A Day of Joy (8:15–17)

2. The Jews Kill Many, Including Haman’s Ten Sons (9:1–10)

3. Esther Asks for Their Bodies to Be Displayed and for a Second Day of Killing in Susa (9:11–19)

III. Purim Established (9:20–32)

A. Mordecai Writes to the Jews of Persia (9:20–28)

B. Esther Writes to Confirm Mordecai’s Letter (9:29–32)

IV. The Greatness of Mordecai (10:1–3)

![]()

![]()

![]()